Coumarin compound DCH combats methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection via inhibiting bacterial arginine repressor.

Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus infection is difficult to eradicate because of biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. The increasing prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection necessitates the development of a new agent against bacterial biofilms. We report a new coumarin compound, termed DCH, that effectively combats MRSA in vitro and in vivo and exhibits potent antibiofilm activity without detectable resistance. Cellular proteome analysis suggests that the molecular mechanism of action of DCH involves the arginine catabolic pathway. Using molecular docking and binding affinity assays of DCH, and comparison of the properties of wild-type and ArgR-deficient MRSA strains, we demonstrate that the arginine repressor ArgR, an essential regulator of the arginine catabolic pathway, is the target of DCH. These findings indicate that DCH is a promising lead compound and validate bacterial ArgR as a potential target in the development of new drugs against MRSA biofilms.

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by biofilm-associated pathogens are difficult to eradicate; thus these infections can transform from acute to chronic stage and lead to serious complications (1, 2). The National Institutes of Health estimates that over 80% of bacterial infections are accompanied by biofilm formation, and about 17 million new biofilm-associated infections annually arise in the United States (3). The three-dimensional structure, extracellular matrix, and inter-bacterial signaling characteristic of microbial biofilm communities promote bacterial growth and persistence and contribute to the antibiotic resistance of biofilm bacteria.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most frequent causes of biofilm-associated clinical infections (4). The increasing emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), antibiotic resistance, and biofilm-forming capacity contribute to S. aureus being the most commonly identified pathogen in both health care and community settings (5), and the ability to acquire novel antibiotic resistance mechanisms makes MRSA a major global health threat (6).

Formation and maintenance of S. aureus biofilms are under the control of complex regulatory circuits. Accessory gene regulator (Agr) is thought to represent the main mechanism that senses the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) and modulates bacterial cell density (7, 8). In addition, production of the intercellular adhesion (icaADBC) gene cluster, which is responsible for the synthesis of PIA or poly-N-acetylglucosasmine (PNAG), is the best-understood mechanism of biofilm production (9, 10). Although Agr is necessary for S. aureus biofilm formation and dissemination, S. aureus strains with a defect in agr function are also frequently isolated from bacteremic patients (11, 12), and in some cases, the agr-negative strains adhere significantly better to host cells than the agr-positive strains (13). Moreover, agr-deficient S. aureus strains form more robust biofilms as compared with wild-type (WT) strains and show increased biofilm development and colonization in animal models (14–16). Thus, the mechanisms by which S. aureus cause biofilm formation and protect themselves against antibiotics remain poorly understood.

Recently, results from our group and other laboratories show that coumarin derivates have potent activity against many pathogens including S. aureus (17–19); however, the antibacterial biofilm activity and the possible target of the coumarin derivates remain uncertain. In this study, we synthesize 667 small molecules including the coumarin derivates and other derivates of hydropyran, hydroquinoline, diludine, and acridine with similar chemical moiety to the coumarin ring, and identify a new coumarin derivate 3,3′-(3,4-dichlorobenzylidene)-bis-(4-hydroxycoumarin) termed DCH, which potently inhibit MRSA and biofilm formation without detectable resistance. The anti-MRSA activity of DCH is most likely through targeting bacterial arginine repressor (ArgR), which provides the basis and strategies for developing new anti-MRSA infection agents.

RESULTS

DCH displays potent activity against MRSA in vitro and in vivo

To identify the possible antibacterial small-molecular chemical compounds, we synthesized and observed the bactericidal activity of 26 series of chemical compounds including coumarin, hydropyran, hydroquinoline, diludine, and acridine derivatives (table S1). These different types of compounds displayed various bioactivities including antibacterial activity, and among these compounds, a new series of biscoumarins were synthesized and one biscoumarin derivative DCH (Fig. 1A) showed activity against S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis with minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) ranging from 4 to 32 μg/ml but was ineffective against Gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella typhimurium, and Acinetobacter baumannii, and the MICs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium smegmatis were 256 and 128 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1). Characterizations of DCH were confirmed by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), 13C NMR, and high-resolution mass spectrometry. The crystal structure refinement of DCH is given in fig. S1.

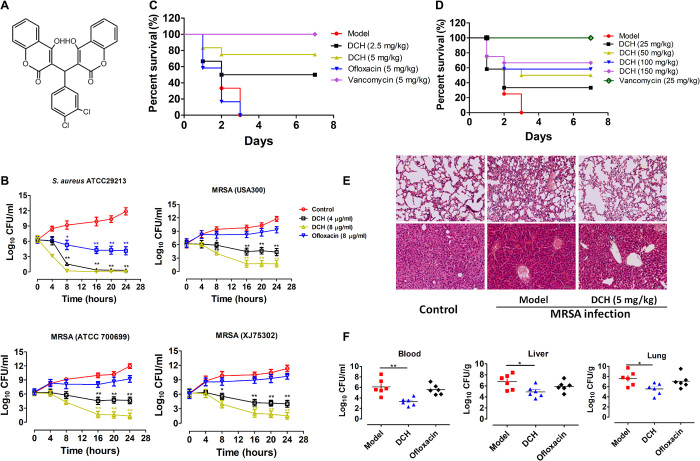

Fig. 1. Anti-MRSA activity of DCH in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Chemical structure of compound DCH. (B) S. aureas (ATCC 29213) and MRSA strain (ATCC 700699, USA300, XJ 75302) were treated with 4 or 8 μg/ml of DCH and ofloxacin (8 μg/ml) as the reference antibacterial agent. n = 6; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus control. (C) In vivo antibacterial effects of DCH in mice infected with MRSA USA300. Survival of BALB/c mice (n = 9) inoculated by intraperitoneal injection with USA300 (5.6 × 108 CFU) and then treated with saline as control (model), ofloxacin (5 mg/kg), vancomycin (5 mg/kg), and DCH (2.5 and 5 mg/kg). (D) Survival of BALB/c mice (n = 12) inoculated by intraperitoneal injection with USA300 (5.6 × 108 CFU) and then intragastric administration of DCH at 25, 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg dosages with saline as control (model) and vancomycin (25 mg/kg) as the positive control. (E) Morphology of the lung and liver examined with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in normal control BALB/c mice; MRSA infection of BALB/c mice with or without DCH (5 mg/kg) treatment (original magnification, ×200). (F) CFUs of MRSA in the blood, lung, and liver cultures of model control, DCH-, and oflocaxin-treated BALB/c mice. n = 6; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus model control group.

Table 1. Activity of DCH against pathogenic bacteria.

The MIC was determined by broth microdilution. MSSA, methicillin-susceptible S. aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; MDR, multidrug resistant.

| Microorganism | MIC (μg ml−1) |

| G+ bacteria | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA, ATCC 29213) | 4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, USA300) | 4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, VISA, ATCC 700699) | 4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, clinical strain XJ 75302) | 4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, clinical strain XJ 141240) | 8 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA, clinical strain XJ 140718) | 4 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (ATCC 14990) | 8 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE, clinical strain) | 8 |

| Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) | 32 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC 49619) | 64 |

| G− bacteria | |

| Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) | >256 |

| Escherichia coli (MDR, ATCC 35218) | >256 |

| Escherichia coli (MDR, clinical strain XJ 74283) | >256 |

| Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (0157:H7) | >256 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) | >256 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MDR, clinical strain XJ 75315) | >256 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ΔmexB PAO1 strain) | >256 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ΔmexN PAO1 strain) | >256 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ΔmexW PAO1 strain) | >256 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ΔmuxA PAO1 strain) | >256 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae(MDR, ATCC 75297) | >256 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (ATCC 19606) | >256 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (clinical strain XJ 17014279) | >256 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (clinical strain XJ 17014346) | >256 |

| Salmonella typhimurium (SL 1344) | >256 |

| Salmonella typhimurium (clinical strain) | >256 |

| Mycobacterium | |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis (ATCC 70084) | 128 |

| Mycobaterium tuberculosis (H37Rv) | 256 |

We further observed the growth inhibitory effects of DCH against the methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strain [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 29213] and MRSA strains (ATCC 70699, USA300, and XJ 75302). The number of colony forming units (CFUs) was calculated from the number of colonies growing on the plates. The results showed that the growth of both MSSA and MRSA strains was apparently inhibited by DCH at 4 or 8 μg/ml. In contrast, the growth of all S. aureus strains in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth without DCH, which was used as the control sample, did not exhibit any significant inhibitory effect. Although the reference quinolone antibacterial agent ofloxacin could significantly inhibit the growth of S. aureus ATCC 29213 at 8 μg/ml, it had no effect on the growth of MRSA strains (Fig. 1B).

Next, we investigated the in vivo therapeutic effect of DCH on MRSA infection. All mice infected with the MRSA strain (USA300) in the control group or in the ofloxacin-treated (5 mg/kg) group died within 3 days, while intraperitoneal administration of 2.5 and 5 mg/kg DCH improved the survival rate to 56 and 67%, respectively (Fig. 1C). Meanwhile, intragastric administration of DCH at 25, 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg dosages improved the survival rate to 33.33, 50, 58.33, and 66.67%, respectively (Fig. 1D). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed abnormal alveolar structure, congestion, necrosis, or infiltration and accumulation of numerous neutrophils in the lung tissue of the control group of MRSA-infected mice. Some neutrophils infiltrated the local alveolar space and alveolar septum, and there was partial alveolar fusion in the DCH (5 mg/kg) intraperitoneally treated group. Swelling of liver cells, hepatic sinusoidal dilation, and congestion were observed in the control group, while these pathological changes were alleviated in the DCH-treated group (Fig. 1E). As survival was related to reductions in bacterial titers in the tissues (blood, lung, and liver), we measured CFUs in the model and DCH or oflocaxin treatment groups. After DCH (5 mg/kg) intraperitoneal treatment, mice that survived lethal MRSA USA300 infection demonstrated an average of three to four log units’ decrease (in CFU) in blood, lung, and liver (Fig. 1F).

DCH inhibits the formation of MRSA biofilm

Because S. aureus is the most important etiological bacteria of biofilm-associated infections on indwelling medical devices, we then evaluated the capacity of the biofilm formation of the MSSA strain (ATCC 29213) and MRSA strains (USA300, XJ 141127, and XJ 1412240) and observed the effect of DCH on the formation of S. aureus biofilm in vitro and in vivo. The 1% crystal violet staining showed that MRSA USA300 was most potent in biofilm formation among the above strains, and the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled bacterial biofilm visualized by fluorescence microscopy showed that the biofilm formation capability of MRSA USA300 was time dependent (fig. S2). At the concentration range of 0.25 to 4 μg/ml, which was below the MIC, DCH could inhibit MRSA biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2, A and B).

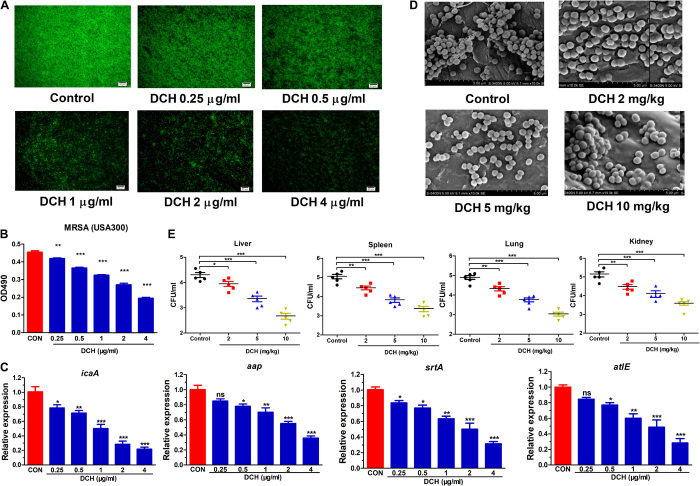

Fig. 2. Inhibitory effect of DCH on the MRSA biofilm formation.

(A) FITC labeling bacterial biofilm formation was shown in control and DCH-treated (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml) MRSA USA300. (B) Results of the 1% crystal violet staining indicated the inhibitory effect of DCH on the MRSA biofilm formation with a dose-dependent relationship. n = 8; **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus control (CON). (C) Expression of icaA, aap, srtA, and atlE was significantly reduced after DCH treatment. n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control. (D) Scanning electron microscopy results showed that DCH treatment at concentrations 2, 5, and 10 mg/kg reduced the production of MRSA USA300 biofilm compared with the control on the catheter surface planted in the rat bladder. (E) CFUs of MRSA USA300 were reduced by DCH treatment (2, 5, and 10 mg/kg) in the liver, spleen, lung, and kidney of bladder biofilm infection rats. n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control. ns, not significant.

Various macromolecules play imperative roles during biofilm formation, biochemical matrix composition, and biofilm spatial organization of S. aureus or S. epidermidis, such as sortase A (srtA), autolysin E (atlE), accumulation associated protein (AAP), and PIA (20, 21). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results confirmed that DCH could significantly inhibit the expression levels of genes including srtA, atlE, aap, and icaA at concentrations below the MIC (Fig. 2C).

We then observed the effect of DCH on the adhesion ability of MRSA to the catheter surface inserted in the rat bladder. Scanning electron microscopy showed that administration of DCH at doses of 5 and 10 mg/kg body weight could inhibit MRSA USA300 adhesion and biofilm formation on the catheter surface (Fig. 2D) and inhibit the spread and growth of MRSA USA300 from the catheter to the liver, spleen, lung, and kidney (Fig. 2E).

Arginine catabolic pathway mediates the antibacterial activity of DCH against MRSA

To reveal the possible target of DCH in anti-MRSA activity, the changes in the cellular proteome was analyzed on the MRSA USA300 strain after DCH treatment using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) (Fig. 3A). These gene ontology (GO) term enrichment differentially expressed proteins were profiled and categorized into 38 cluster of orthologous groups (COGs), indicative of a drastic change as well as a global response to DCH treatment (Fig. 3B), and a total of 239 of 1647 proteins were differentially expressed (fold change, >1.2; P < 0.05), of which 97 proteins were up-regulated and 147 proteins were down-regulated, as confirmed by clustering analysis. Enzymes involved in arginine catabolic pathways showed the maximal expression changes after DCH treatment, including ornithine carbamoyltransferase (difference, 0.238), arginine deiminase (difference, 0.287), glycine cleavage system protein H (difference, 0.497), and carbamate kinase (difference, 0.509), which were among the top six most significantly down-regulated proteins (table S2 and Fig. 3C).

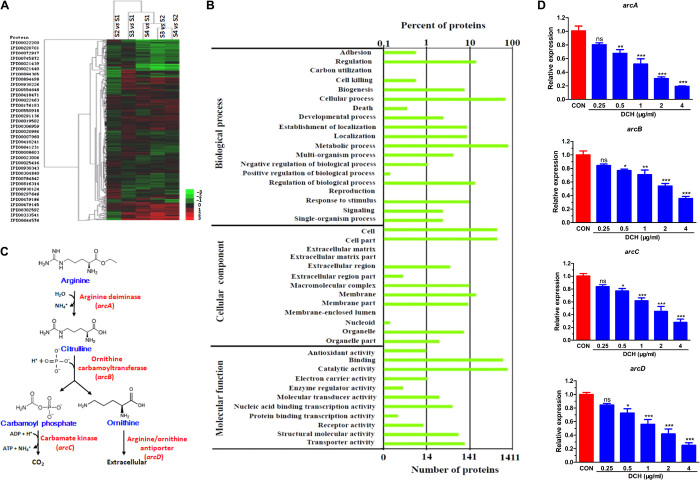

Fig. 3. Arginine catabolic pathway mediated the effect of DCH.

(A) Proteome changes in MRSA USA300 after DCH treatment using iTRAQ labeling. (B) Thirty-eight COG enrichment differentially expressed proteins were profiled. (C) Ornithine carbamoyltransferase, arginine deiminase, and carbamate kinase were involved in S. aureus arginine catabolic pathway. (D) Expression of arc gene cluster (arcA, arcB, arcC, and arcD) was significantly reduced after DCH treatment at concentrations of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml. n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus control (CON).

Given that arginine deiminase, ornithine carbamoyltransferase, and carbamate kinase are encoded by arcA, arcB, and arcC genes, respectively, DCH may affect the MRSA arc gene cluster transcription. Hence, we analyzed the mRNAs of arc genes isolated from cultures of control and DCH-treated MRSA USA300 strains. Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) results showed that DCH treatment significantly reduced the expression of arcA, arcB, arcC, and arcD (encoding the arginine/ornithine antiporter) at a concentration range of 0.5 to 4 μg/ml (Fig. 3D).

DCH binds to bacterial ArgR with high affinity

Because of the inhibition of expression of arc genes by DCH treatment, transcriptional regulators of the arc cluster may be the target of DCH. Because hexameric ArgR has been implicated as the master transcriptional repressor of arc genes in a wide range of bacteria including S. aureus (22, 23), we studied the binding affinity and site of DCH to ArgR using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) titration and molecular docking. The ArgR recombinant protein was overexpressed by transforming recombinant plasmid pET28a-ArgR into E. coli BL21. The purified ArgR protein was subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and the concentration of the protein was 92.1%. Relative SPR response unit (RU) was induced by DCH in a dose-dependent manner from 0.5 to 8 μM (Fig. 4A). The fit (continuous line) yields of the Ka (Ms−1), Kd (s−1), and KD (M) between the total 15 compounds and ArgR are listed in table S3. Consistent with the MICs, the KD of DCH was 8.2 × 10−8 M, which indicated that DCH had a high affinity for ArgR protein.

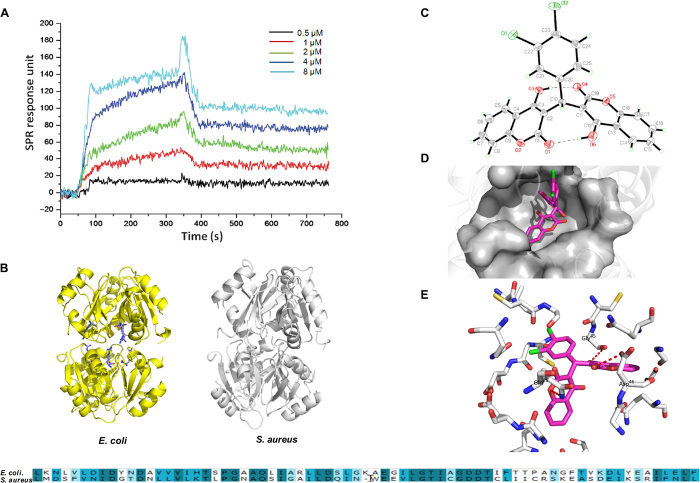

Fig. 4. The binding affinity and site of DCH to bacterial ArgR.

(A) Relative RU was induced by DCH in dose-dependent model from 0.5 to 8 μM. (B) Homology model building of S. aureus ArgRC (right) was performed according to the sequence alignment with the E. coli ArgRC (left); the sequence alignment result of ArgR C-terminal residues between E. coli and S. aureus is shown in bottom. (C) Crystal structure diagram of the asymmetric unit including the atomic numbering scheme of compound DCH. (D) Overview of the docked pose showed that DCH shared a very similar binding pocket to arginine in the ArgRC. (E) The 3D schematic showed two noticeable interactions between the benzene rings of DCH and two amino acids (GLN25 and ASP46) of ArgRC in the active site.

The affinity of ArgR to operator DNAs can be promoted by arginine binding, and the binding sites of arginine are buried deep within the C-terminal domain of the ArgR (ArgRC), which is distant from the peripheral DNA binding domains (24). ArgR appears to activate catabolism by antirepression in an arginine-dependent way, which indicates that DCH treatment reduced the expression of arc genes possibly through binding to ArgRC and increased the affinity of ArgR for DNAs. Because of the poorly characterized 3D crystal structure profile of S. aureus ArgR, we searched the homology of sequence alignment of ArgRC residues in the Protein Data Bank and selected the E. coli ArgRC (template PDB ID: 1XXB) as the top score homology model, which was 70.42% identical in amino acid sequence to S. aureus ArgRC. Then, sequence alignment and homology model building were performed by Modeller in Discovery Studio 3.5 (Fig. 4B).

In the crystal structure of DCH, two 4-hydroxycoumarin fragments are linked by a methylene bridge (Fig. 4C), and molecular docking results showed that DCH shared a very similar binding pocket to arginine in the complex overview of the docked pose (docking score,: −5.07), and molecular docking was performed by Glide 5.5 in Schrodinger 2011 (Fig. 4D). The 3D schematic showed two noticeable interactions between the benzene rings of DCH and two amino acids (GLN25 and ASP46) of ArgRC in the active site. This binding conformation could be stabilized by the interaction between the DCH carbonyl group on the benzene rings and the hydrophobic amino acid residue (GLY45) around the active pocket (Fig. 4E). These results were similar to the binding sites of l-arginine to ArgR, which were buried deep within the C-terminal domain of the protein, and contributed to the transcriptional control and recombination in E. coli (25).

Deletion of ArgR reduces biofilm formation of MRSA through the arginine catabolic pathway

To further confirm the contribution of ArgR to the survival and biofilm formation of MRSA, argR gene encoding ArgR was deleted (ΔargR) in the MRSA USA300 strain by homologous recombination in RN4220 and confirmed by PCR and DNA sequencing (fig. S3). Compared to the WT MRSA USA300 strain, the growth of ΔargR MRSA was reduced by >50%. DCH treatment could not inhibit the growth of ΔargR MRSA USA300. In addition, deletion of ArgR significantly impaired the biofilm formation of MRSA USA300 (fig. S4A) and reduced the expression of biofilm-related genes (srtA, icaA, atlE, and aap) by about 60% as compared to the WT strain. Consistent with the effect on growth of the MRSA USA300 strain, DCH treatment (2 μg/ml) could not alter the biofilm-related gene expression in the ΔargR MRSA strain (fig. S4B), suggesting that the activity of DCH against MRSA was mainly through the inhibitory effect on ArgR.

Numerous bacterial species deploy ArgR to accelerate arginine metabolism in the presence of arginine, which enhances their capacity to survive under multiple environmental stress conditions (23, 26). Arginine, citrilline, and ornithine are the key amino acids involved in the arginine catabolic pathway of living organisms, and their metabolites such as polyamines including putrescine, spermidine, and spermine are involved in the mechanisms of adapting to environmental nutrient availability (4, 27, 28). Given that the expression of the arc gene cluster was repressed after DCH treatment or ArgR deletion, our results also showed that intracellular arginine level was enhanced more than twofold (P < 0.01), while ornithine was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) after DCH (2 μg/ml) treatment in both WT and ΔargR USA300 strains (fig. S4C). Furthermore, compared to the control, DCH treatment also significantly reduced the intracellular spermidine and spermine levels of the MRSA USA300 strain, while the level of putrescine was below the limit of detection (fig. S4, D and E).

Druggability and resistance development evaluation of DCH

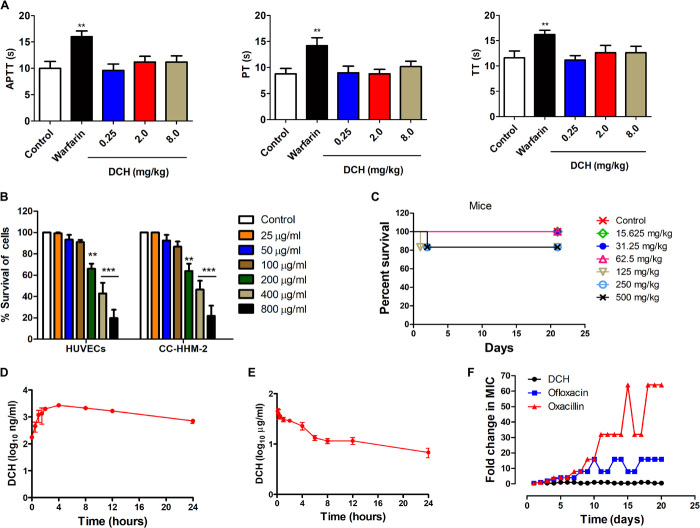

Coumarins are reported to target the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex, contributing significantly to the vitamin K cycle and benefitting the anticoagulation therapy (29). We then detected the activity of DCH to the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrinogen prothrombin time (PT), and thrombin time (TT). Compared with the classic coumarin anticoagulant warfarin (0.25 mg/kg), DCH did not show anticoagulation activity at the concentrations of 0.25, 2, and 8 mg/kg (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Druggability and resistance development evaluation of DCH.

(A) APTT, PT, and TT were prolonged in groups of rabbits treated with warfarin (0.25 mg/kg per day) but not DCH (0.25, 2, and 8 mg/kg per day) compared with control. **P < 0.01; n = 5. (B) Cell toxicity of DCH (ranging from 25 to 800 μg/ml) determined on HUVECs and CC-HHM-2 cells after 24 hours of incubation; data points are represented as means ± SD of three replicates. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus control. (C) Percent survival was measured after the 21-day-period intragastric administration of DCH at doses of 15.625, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 mg/kg daily in mice. (D) Quantification of DCH plasma concentrations in rat blood at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, or 24 hours after intragastric administration at 14 mg/kg dosage (n = 3). (E) Quantification of DCH plasma concentrations in rat blood at 0.083, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, or 24 hours after intravenous administration at 5 mg/kg dosage (n = 3). (F) Resistance development of S. aureus ATCC 29213 to DCH, ofloxacin, and oxacillin. Values are fold changes (in log2) in MIC relative to the MIC of the first passage.

Furthermore, the cytotoxicity of DCH to the cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and cells from human embryonic myocardial tissue (CC-HHM-2) was measured. The results showed that DCH exhibited cell toxicity against HUVECs and CC-HHM-2 at concentrations higher than 200 μg/ml (Fig. 5B), which was more than 50 times higher than MIC for MRSA USA300. Then, in vivo acute toxicity was evaluated in mice and rats. After a single, oral, daily administration of DCH at doses of 15.625, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 mg/kg in mice, or 1000, 2150, 4650, and 10,000 mg/kg in rats, death and toxicity signs were observed during the 21-day period. The median lethal dose (LD50) of DCH was 1878 mg/kg in mice (Fig. 5C) and 3690 and 6190 mg/kg in male and female rats, respectively. According to the acute toxicity standard of the World Health Organization, DCH belonged to chemical compounds with low toxicity. Moreover, the therapeutic index of DCH in mouse was 37.56, indicating that DCH had considerable in vivo efficacy with large therapeutic index. The analysis of blood after a single-dose intragastric administration of DCH at 14 mg/kg dosage revealed that the plasma concentration of DCH rapidly increased, with a half-life of 10 ± 1.33 hours (Fig. 5D). Meanwhile, the half-life of DCH was 15 ± 2.69 hours after intravenous administration at 5 mg/kg dosage, and the bioavailability of DCH was 4.2% (Fig. 5E); the poor oral bioavailability of DCH was possibly mainly attributed to its low aqueous solubility.

Most antimicrobial drugs introduced into the clinic have been proven to have finite efficacy and life span, as resistance always emerges (30, 31). For single-step resistance, we were unable to obtain mutants of S. aureus resistant to DCH at 2×, 4×, and 8× MIC concentration. Serial passage of S. aureus in the presence of 0.25× and 0.5× MIC levels of DCH over a period of 21 days failed to produce resistance as well. However, the relative MIC values of ofloxacin and oxacillin increased by 16- and 64-fold, respectively (Fig. 5F). These results suggested that despite low oral bioavailability, DCH would be a promising anti-MRSA lead without associated in vitro and in vivo toxicity and detectable resistance.

DISCUSSION

Small molecules containing a coumarin moiety display antibacterial efficacy against MRSA (32–34). In this study, coumarin derivate DCH exhibited the selective in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity against MRSA; however, DCH had no obvious activity against Gram-negative bacteria including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and Salmonella typhimurium, and WT P. aeruginosa and efflux pump mutant or deleted stains including ΔmexB, ΔmexN, ΔmexW, and ΔmuxA P. aeruginosa. These results indicated that the selective activity of DCH against Staphylococcus was perhaps due to the difference in the possible target or cellular structure between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

In this study, some new 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives were demonstrated to be capable of remarkably inhibiting the growth and biofilm formation of MRSA USA300 strain, and dihydropyran derivatives almost had no antibacterial activities. The differences in bioactivity among these 4-hydroxycoumarin compounds might be due to different substituent groups and their positions. Because of the absence of the benzene ring moiety in the substituent group, the compound had no antibacterial activity and affinity to the ArgR protein. However, the compounds contained electron-withdrawing substituent groups, such as fluoro, chloro-, bromo-, and fluoromethyl groups, showing potent antibacterial activity and higher affinity binding to the argR protein. The data of 4-hydroxycoumarin derivative crystal structures revealed the 3D quantitative structure-activity relationships of these compounds with the affinity for MRSA ArgR.

Biofilm formed by S. aureus significantly enhances antibiotic resistance and severity of infection (35, 36). Our study showed that DCH could inhibit the biofilm formation of MRSA in vitro and in vivo. The cellular proteome and transcription profiling demonstrated that the arginine catabolic pathway was obviously inhibited by DCH treatment. ArgR is the key regulator of arcABCD operon expression in many bacterial species (37, 38), and presence of arginine leads to diminished binding of ArgR to the arc promoter (39), allowing catabolism of arginine through the arc-encoding enzyme degradation pathway. Three observations in this study provided evidence for ArgR as the possible target of DCH: (i) The high binding affinity of DCH to ArgR in a dose-dependent model and the affinity of 15 coumarin compounds are consistent with the MICs; (ii) the similarity of the binding site of DCH to ArgR C terminal, as compared with arginine; (3) argR deficiency impaired the biofilm formation of MRSA, and DCH treatment could not further inhibit the expression of biofilm-related genes in argR-deficient MRSA USA300 strain. Certainly, more evidence is needed to confirm the ArgR as the target of DCH, such as the crystal structure of the intermediate complex of the ArgR from MRSA bound with its DNA operator and DCH for revealing the detailed mechanism.

The arginine catabolic pathway is the major source for polyamine biosynthesis in S. aureus, which plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of MRSA and other bacteria (40, 41). Spermidine and norspermidine, a structural analog of spermidine, are known to be essential for robust biofilm production and development in numerous bacteria, including clinical multidrug-resistant isolates (42–44). Consistent with these observations, DCH treatment or argR deficiency could reduce the level of intracellular spermine and spermidine by blocking the arginine catabolic pathway, and contributed to the biofilm inhibitory activity. However, intracellular putrescine was not detected in the control or DCH-treated MRSA. Hence, it is unclear whether endogenous putrescine level is altered in this case, and it is difficult to evaluate its functions in biofilm development in contrast to the stimulatory role of other polyamines.

To the best of our knowledge, coumarin derivate DCH is probably the only known small molecular compound that can competitively bind to ArgR to date. Because of the absence of ArgR in eukaryotic cells, bacterial ArgR is an attractive and druggable target against MRSA infection associated with biofilm. Although the MIC of DCH is not as low as clinical anti-MRSA agents such as vancomycin, the druggability evaluation and resistance development data of DCH highlight its role as a promising therapeutic candidate against MRSA.

In summary, this is the first study to reveal that a new coumarin derivate DCH combats MRSA biofilm infection, possibly by competitively binding to ArgR; subsequently suppresses the biosynthesis of intracellular ornithine and polyamines; and, lastly, reduces the production of biofilm-associated virulence factors. Our findings also encourage future investigation of potential novel antibiotics targeting this signaling pathway to combat MRSA infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis and characterization of compounds

The series 1 to 4 of compounds were synthesized and characterized according to the method reported in previous studies (17–18); in brief, a mixture of aromatic aldehyde (10 mmol) and 4-hydroxycoumarin (or 3,5-cyclohexanedione, 1,1-dimethyl-3,5-cyclohexanedione) (20 mmol) was dissolved in 100 ml of EtOH (or Ac2O for series 2). A few drops of piperidine were added, and the mixture was stirred for 3 hours at room temperature. After the completion of reaction, as determined by TLC (thin-layer chromatography), water was added until precipitation occurred. Series 5 to 20 of compounds: A mixture of 1,1-dimethyl-3,5-cyclohexanedione (or 3,5-cyclohexanedione, 4-hydroxycoumarin, 1-naphthol, 2-naphthol, resorcinol, 4-hydroxy-6-methyl-2-pyrone, kojic acid, 1,3-cyclopentanedione, 1-methyl-4-piperidone) (10 mmol), aromatic aldehyde (10 mmol), malononitrile (or ethyl cyanoacetate, ethyl trifluoroacetate) (10 mmol), and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) (1 mmol) in ethanol (100 ml) was refluxed for 2 to 3 hours and then cooled to room temperature. Series 21 to 24 of compounds: A mixture of 1,1-dimethyl-3,5-cyclohexanedione (or 3,5-cyclohexanedione) (10 mmol), aromatic aldehydes (10 mmol), and 3-amino-2-butenoicacimethylester (or ammonium acetate and ethyl acetoacetate) (10 mmol) in ethanol (100 ml) was refluxed for 2 to 3 hours and then cooled to room temperature. Series 25 of compounds: A mixture of aromatic aldehyde (10 mmol), ammonium acetate (10 mmol), and ethyl acetoacetate (10 mmol) in ethanol (100 ml) was refluxed for 2 to 3 hours and then cooled to room temperature. Series 26 of compounds: A mixture of 3,5-cyclohexanedione (20 mmol), aromatic aldehyde (10 mmol), and ammonium acetate (10 mmol) in ethanol (100 ml) was refluxed for 2 to 3 hours and then cooled to room temperature. After filtering the precipitates, all the compounds were sequentially washed with ice-cooled water and ethanol and then dried under a vacuum. Infrared spectra were measured using a Brucker Equinox 55 spectrophotometer (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen, German). 1H NMR spectra, 13C NMR spectra, and mass spectra were tested using the Varian Inova 400 spectrometer (Varian Inc., CA, USA), Bruker Avance III spectrometer (Bruker Optics), and micrOTOF-Q II mass spectrometer (Bruker Optics), respectively. Single crystal of DCH for x-ray diffraction experiments was obtained by slow volatilization of its MeOH solution in a test tube for 1 week. The x-ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker SMART APEX II CCD (charge-coupled device) diffractometer equipped with a graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) using ω-2θ scan technique at room temperature. Parameters in the common intermediate format were available as Electronic Supplementary Publication from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Bacterial strains and cells

MRSA (ATCC 700699, USA300), S. epidermidis (ATCC 14990), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212), S. pneumoniae (ATCC 49619), E. coli (ATCC 25922, ATCC 35218), P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), K. pneumoniae (MDR, ATCC 75297), A. baumannii (ATCC 19606), M. smegmatis (ATCC 70084), HUVECs, and CC-HHM-2 were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, USA). S. aureus (ATCC 29213), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (0157:H7), S. typhimurium (SL 1344), and M. tuberculosis (H37Rv) were obtained from the Chinese National Center for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (Beijing, China). The clinical MRSA strains (XJ 75302, XJ 141240, and XJ 140718), E. coli (XJ 74283), P. aeruginosa (XJ 75315), and A. baumannii (XJ 17014279 and XJ 17014346) were obtained from Xijing Hospital (Xi’an, China).

MIC assay

Bacterial strains were grown overnight in MH broth at a concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml in microtiter plates. Then, 100 μl of culture medium containing different concentrations of test derivates and reference antibiotics were added to the plates. After incubating for 20 hours at 37°C, 50 μl of 0.2% triphenyl tetrazolium chloride was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at 35°C. The MICs were detected as the lowest concentration of derivates that showed no red color change.

Bacterial growth curves analysis

The effect of DCH on the bacterial growth curves of S. aureus was measured as follows: The S. aureus strains were cultivated using MH broth medium in the automated Bioscreen C system (Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland), and different concentrations of DCH were added to the medium. The total working volume in the wells was 300 μl, including 150 μl of MH broth and 150 μl of compound solutions. The density of the cell suspensions was detected at 600 nm at 10-min intervals for 24 hours at 35°C.

In vivo antisepsis activity

Mice were infected by intraperitoneal administration of 5.6 × 108 CFU MRSA USA300 in 0.4 ml of MH broth. After bacterial challenge for 1 hour, mice were randomized to receive intraperitoneal injection of saline as a control, ofloxacin (5 mg/kg), vacomycin (5 mg/kg), or DCH (2.5 and 5 mg/kg), or intragastric administration of DCH at 25, 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg dosages. The survival of mice in each group was monitored for 7 days after infection, and the cumulative percentage survival was determined. To assess bacterial clearance, six mice in each group were euthanized, and bacterial counts were determined in the liver, lung, and blood from each animal after bacterial challenge for 24 hours. In the MRSA infection model, parts of lung and liver tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours, and then their morphologies were observed using H&E staining. This animal experiment was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Fourth Military Medical University (no. XJYYLL-2015667).

Biofilm formation assay

S. aureus strains were seeded in 96-well microtiter plates with 200 μl of tryptic soy broth (TSB) containing 0.5% glucose. DCH was added to each well, and equal volume of TSB medium was added as control. Biofilm formation was determined by crystal violet staining. The optical density (OD) of each well was measured at 630 nm using an automated ELx800 universal microplate reader (Bio-Tek, USA). Each experiment was repeated three times, with at least eight wells of each sample.

Morphology assays using transmission electron microscopy

MRSA USA300 (1.0 × 108 CFU/ml) was cultured in MH broth with or without DCH (4 μg/ml) at 120 rpm for 90 min. Then, the specimens were observed with a JEM-1230 transmission electron microscope (JOEL, Japan).

Bacterial adherence assay

MRSA USA300 was seeded in 96-well microtiter plates with 200 μl of TSB containing 0.5% glucose. DCH was added to each well to reach a final concentration of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml, and an equal volume of TSB medium was added as control. Then, FITC was added into each well to label the bacteria. The bacteria were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. After extensive washing of the wells with phosphate-buffered saline, the adhered cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus CKX41) at 488 nm.

Antibiofilm-related infection activity assay

The rats were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg). A 1.5-cm incision was made along the median line to expose the bladder, and then the incision was made at the dome under aseptic conditions. An 8-mm sterile stent was inserted into the urinary bladder. After the surgical intervention, 0.2 ml of nutrient broth containing MRSA USA300 (1 × 106 CFU/ml) was inoculated into the bladder. Rats received 2, 5, and 10 mg/kg doses of DCH after bacterial challenge. Three days after infection, the kidney, spleen, lung, and liver of rats were extracted and then homogenized. The implanted stents were removed and prepared for scanning electron microscopy examination (Hitachi S-3400N, Japan). Quantization of viable bacteria was performed by culturing serial dilutions (0.1 ml) of the bacterial suspension on MH agar plates.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA from the MRSA USA300 strain was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and then RNA was reverse transcribed using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit with DNA Eraser. PCR was performed with the Premix Taq RT-PCR System (Takara Bio, Kyoto, Japan). Specific primers are listed in tables S4 and S5. The PCRs were performed in a 20-μl volume and contained ABI SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. Amplification was performed in a gradient thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA). 16S rRNA was used as an internal control. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation

MRSA USA300 at mid-log phase was cultured and treated with DCH. Three independent biological replicates were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and then precipitated using trichloroacetic acid and acetone. The pellets were suspended in lysis buffer (4% SDS, 100 mM tris-HCl, and 1 mM DTT, pH 7.6) and heated for 10 min at 100°C. The protein concentration in supernatants was determined by Bradford protein assay. iTRAQ reagent was dissolved in 70 μl of ethanol and added into the peptide mixture; then, the reaction was quenched by adding 0.5% formic acid. The labeled peptides were combined and fractionated using strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography.

Expression and purification of ArgR recombinant protein

The argR gene was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies based on its sequence in the MRSA USA300 strain. The PCR product was ligated to modified pET28a with the same restriction enzymes to generate the recombinant plasmid pET28a-ArgR using T4 DNA ligase. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into TOP10, and the transformed bacteria were selected by screening the colonies on kanamycin (100 μg/ml)–containing agar plates. After amplification, the colonies were further analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion and PCR sequencing. A single transformed bacterial colony was incubated in LB medium containing kanamycin (100 μg/ml). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM for inducing the expression of argR gene in E. coli. The expressed protein was purified using Ni-NTA agarose column from the harvested bacterial suspension. Then, the quality and quantity of purified recombinant ArgR were analyzed on 12% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis.

SPR analysis

SPR experiments were performed using a Biacore T200 system (GE Life Sciences, USA). ArgR was immobilized using capture/coupling amine chemistry. The chip was preconditioned with an injection of 0.5 M NiCl2 for 60 s, and the surface was activated with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC). To collect kinetic-binding data, the compounds in running buffer [50 mM tris, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, and 5% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (pH 7.5)] were injected over the two flow cells at concentrations between 2 nM and 1 μM at a flow rate of 30 μl/min. Compounds was prepared at concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 μg/ml. Data were collected at a rate of 10 Hz and fitted to a simple 1:1 interaction model using the global data analysis option in the Biacore T200 evaluation software.

Construction of argR-deficent MRSA USA300 mutant

The complete argR open reading frame along with its promoter was amplified from genomic DNA using primer pairs listed in table S6. The genomic DNA was obtained by DNA kit (Omega, USA) after digestion with 5 μl of lysostaphin (10 mg/ml) and 5 μl of RNase (ribonuclease A). The PCR product was cloned into pMAD plasmid containing Bgl II and Bam HI. The resultant plasmid was electroporated into the MRSA USA300 strain. Plasmid-containing cells were selected on LB agar plates containing chloromycetin (15 μg/ml) and ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry determination of intracellular amino acids

The samples were homogenized and centrifuged for 4 min at 13,200g, and the separations were performed on a MSLab45AA-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm; particle size, 5 μm) at 50°C using an UltiMate 3000 HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) system and Applied Biosystems API 3200 QTRAP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Eluents A and B were 10 mM aqueous ammonium formate buffer (pH 4.5) and acetonitrile, respectively. The flow rate was set to 1 ml/min. The ion source parameters were set as follows: curtain gas, 20 psi; ion spray voltage, 5500 V; ion source temperature, 500°C; and nebulizing and drying gas, 55 psi. The injection volume was 50 μl.

HPLC analysis of polyamine levels

The samples were homogenized in 700 μl of 0.9% sodium chloride mixed with 10 μl (200 nmol/ml) of internal standard (1,7-diaminoheptane). To precipitate proteins, 300 μl of trichloroacetic acid (0.5 M) was added to the homogenate. After 30 min of incubation in ice, the homogenate was centrifuged for 30 min at 14,500g at 4°C. The derivatization reaction was carried out with 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate, and the fluorescent polyamine derivatives were performed using C18 HPLC columns with a fluorescence detector (Jasco 821-FP, Japan). The excitation and emission wavelengths of the detector were set at 264 and 310 nm, respectively. The solvent flow was 2 ml/min (acetonitrile:acetate 60/40 v/v) and was followed by a linear increase in acetonitrile concentration to 95% in 30 min. The samples were dissolved in 50 mM sodium acetonitrile:acetate 50/50 (v/v). The injection volume was 20 μl.

Anticoagulant activity assay

Thirty New Zealand white rabbits were randomized into five groups, with six rabbits in each group. Control group was administered normal saline. The warfarin treatment group was administered warfarin 0.25 mg/kg per day. The DCH treatment groups were administered different doses of DCH (0.25, 2, and 8 mg/kg per day, respectively). The duration of treatment was 5 days. Blood samples were collected from auricular arteries of fasting animals. A total of 2.5 ml of blood was collected from each animal in sodium citrate blood collection tubes. The APTT, PT, and TT were calculated.

Cytotoxicity test

HUVECs and CC-HHM-2 cells were used in the cytotoxicity test. Cultured cells were treated with DCH at various concentrations at 800, 400, 200, 100, 50, 25, and 12.5 μg/ml, and cell viability was determined with the MTT assay. The OD values were calculated in terms of relative cytotoxicity compared with control. The experiment was performed in duplicate, and the average from five independent experiments was reported.

Acute toxicity assay

A total of 50 rats (25 male and 25 female rats) were randomly allocated to five groups (solvent group; 1000, 2150, 4640, and 10,000 mg/kg intragastric administration of DCH) with 10 animals per sex and dose group. In addition, 42 mice (21 male and 21 female mice) were randomly allocated to seven groups (solvent group, and intragastric administration of DCH at doses of 15.625, 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, and 500 mg/kg), with six animals per dose group. All the groups were closely observed every day at a regular interval of 8 hours for 3 weeks. The weight of the animals was monitored, and the animals that survived were observed for other toxic effects. Last, the animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and vital organs such as heart, lungs, liver, stomach, small intestine, kidneys, spleen, testes, and ovary were excised, weighed, and preserved in 10% formalin for histopathological change evaluation.

Bacterial resistance development studies

For single-step resistance, S. aureus (ATCC 29213) at 1 × 1010 CFU were cultured with Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) containing 2×, 4×, and 8× MIC of DCH; then, resistant colonies were detected after incubation for 48 hours at 37°C. For resistance development by sequential passaging, S. aureus (ATCC 29213) cells at the exponential phase were diluted in 1 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) containing DCH or reference antibiotics ofloxacin and oxacillin. The cells were incubated at 37°C with agitation and passaged at 24-hour intervals in the presence of DCH or reference antibiotics at 0.25× and 0.5× MIC concentrations; then, the MIC was determined through broth microdilution.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), two-way ANOVA, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were used for statistical evaluations, with P < 0.05 indicative of statistical significance, and those with P values of 0.01 were considered markedly statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the BGI Cellular Proteome Assay platform for use of iTRAQ. We thank X. Xu (Xijing Hospital, The Fourth Military Medical University, Xi’an, China) for providing the clinical bacterial strains, and L. Chen (College of Life Sciences, Northwest University in China) for providing the ΔmexB, ΔmexN, ΔmexW, and ΔmuxA P. aeruginosa PAO1 strains. We thank the safety evaluation center of United Nation Quality Detection Company (Xi’an, China) for the acute toxicity assay. Funding: This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81573468, 81673477, 81471997, and 81473252). Author contributions: M.L. and X.L. designed the project and wrote the manuscript. D.Q. and L.L. performed the in vitro and in vivo biofilm experiments and morphology observation. Z.H. performed the in vitro antibacterial and pharmacokinetic experiment. J.L. synthesized and characterized the compounds. G.C., Z.L., and S.S. performed the safety and resistance development evaluation. Z.Y. performed the argR mutation and protein purification. X.Z. performed the molecular docking assay. L.L. and X.X. performed the RT-PCR and HPLC assays. Y.B. contributed to the MIC determination of M. tuberculosis. All authors gave suggestions to improve the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/30/eaay9597/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Olsen I., Biofilm-specific antibiotic tolerance and resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 877–886 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham W. R., Going beyond the control of quorum-sensing to combat biofilm infections. Antibiotics 5, E3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joseph R., Naugolny A., Feldman M., Herzog I. M., Fridman M., Cohen Y., Cationic pillararenes potently inhibit biofilm formation without affecting bacterial growth and viability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 754–757 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen H. B., Vaze N. D., Choi C., Hailu T., Tulbert B. H., Cusack C. A., Joshi S. G., The presence and impact of biofilm-producing staphylococci in atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 150, 260–265 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyama T., Miyazaki M., Yoshimura M., Takata T., Ohjimi H., Jimi S., Biofilm-forming methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus survive in kupffer cells and exhibit high virulence in mice. Toxins 8, E198 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii K., Tabuchi F., Matsuo M., Tatsuno K., Sato T., Okazaki M., Hamamoto H., Matsumoto Y., Kaito C., Aoyagi T., Hiramatsu K., Kaku M., Moriya K., Sekimizu K., Phenotypic and genomic comparisons of highly vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains developed from multiple clinical MRSA strains by in vitro mutagenesis. Sci. Rep. 5, 17092 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balaban N., Cirioni O., Giacometti A., Ghiselli R., Braunstein J. B., Silvestri C., Mocchegiani F., Saba V., Scalise G., Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection by the quorum-sensing inhibitor RIP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 2226–2229 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh R., Ray P., Quorum sensing-mediated regulation of staphylococcal virulence and antibiotic resistance. Future Microbiol. 9, 669–681 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy H., Rudkin J. K., Black N. S., Gallagher L., O’Neill E., O’Gara J. P., Methicillin resistance and the biofilm phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 5, 1 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zapotoczna M., O’Neill E., O’Gara J. P., Untangling the diverse and redundant mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLOS Pathog. 12, e1005671 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler V. G. Jr., Sakoulas G., McIntyre L. M., Meka V. G., Arbeit R. D., Cabell C. H., Stryjewski M. E., Eliopoulos G. M., Reller L. B., Corey G. R., Jones T., Lucindo N., Yeaman M. R., Bayer A. S., Persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infection is associated with agr dysfunction and low-level in vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein. J Infect Dis 190, 1140–1149 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweizer M. L., Furuno J. P., Sakoulas G., Johnson J. K., Harris A. D., Shardell M. D., McGregor J. C., Thom K. A., Perencevich E. N., Increased mortality with accessory gene regulator (agr) dysfunction in Staphylococcus aureus among bacteremic patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 1082–1087 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunter J. P., Seth-Smith H. M., Ruegg S., Heikinheimo A., Borel N., Johler S., Wild type agr-negative livestock-associated MRSA exhibits high adhesive capacity to human and porcine cells. Res. Microbiol. 168, 130–138 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vuong C., Saenz H. L., Gotz F., Otto M., Impact of the agr quorum-sensing system on adherence to polystyrene in Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 182, 1688–1693 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beenken K. E., Blevins J. S., Smeltzer M. S., Mutation of sarA in Staphylococcus aureus limits biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 71, 4206–4211 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vuong C., Kocianova S., Yao Y., Carmody A. B., Otto M., Increased colonization of indwelling medical devices by quorum-sensing mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis in vivo. J Infect Dis 190, 1498–1505 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M. K., Li J., Liu B. H., Zhou Y., Li X., Xue X. Y., Hou Z., Luo X. X., Synthesis, crystal structures, and anti-drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus activities of novel 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 721, 151–157 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z. P., Li J., Qu D., Hou Z., Yang X. H., Zhang Z. D., Wang Y. K., Luo X. X., Li M. K., Synthesis and pharmacological evaluations of 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives as a new class of anti-Staphylococcus aureus agents. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 67, 573–582 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh L. K., Priyanka, Singh V., Katiyar D., Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of some new coumarin derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents. Med. Chem. 11, 128–134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu L., Hisatsune J., Hayashi I., Tatsukawa N., Sato’o Y., Mizumachi E., Kato F., Hirakawa H., Pier G. B., Sugai M., A novel repressor of the ica locus discovered in clinically isolated super-biofilm-elaborating Staphylococcus aureus. MBio 8, e02282-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le K. Y., Park M. D., Otto M., Immune evasion mechanisms of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm infection. Front. Microbiol. 9, 359 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makhlin J., Kofman T., Borovok I., Kohler C., Engelmann S., Cohen G., Aharonowitz Y., Staphylococcus aureus ArcR controls expression of the arginine deiminase operon. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5976–5986 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng C., Dong Z., Han X., Sun J., Wang H., Jiang L., Yang Y., Ma T., Chen Z., Yu J., Fang W., Song H., Listeria monocytogenes 10403S Arginine repressor ArgR finely tunes arginine metabolism regulation under acidic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 8, 145 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szwajkajzer D., Dai L., Fukayama J. W., Abramczyk B., Fairman R., Carey J., Quantitative analysis of DNA binding by the Escherichia coli arginine repressor. J. Mol. Biol. 312, 949–962 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Duyne G. D., Ghosh G., Maas W. K., Sigler P. B., Structure of the oligomerization and L-arginine binding domain of the arginine repressor of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 256, 377–391 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong L., Teng J. L., Watt R. M., Kan B., Lau S. K., Woo P. C., Arginine deiminase pathway is far more important than urease for acid resistance and intracellular survival in Laribacter hongkongensis: A possible result of arc gene cassette duplication. BMC Microbiol. 14, 42 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen A. E., Dupont C. L., Obornik M., Horak A., Nunes-Nesi A., McCrow J. P., Zheng H., Johnson D. A., Hu H., Fernie A. R., Bowler C., Evolution and metabolic significance of the urea cycle in photosynthetic diatoms. Nature 473, 203–207 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H., Liu Y., Nie X., Liu L., Hua Q., Zhao G. P., Yang C., The cyanobacterial ornithine-ammonia cycle involves an arginine dihydrolase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 575–581 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verhoef T. I., Redekop W. K., Daly A. K., van Schie R. M., de Boer A., Maitland-van der Zee A. H., Pharmacogenetic-guided dosing of coumarin anticoagulants: Algorithms for warfarin, acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 77, 626–641 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roope L. S. J., Smith R. D., Pouwels K. B., Buchanan J., Abel L., Eibich P., Butler C. C., Tan P. S., Walker A. S., Robotham J. V., Wordsworth S., The challenge of antimicrobial resistance: What economics can contribute. Science 364, eaau4679 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blaser M. J., Antibiotic use and its consequences for the normal microbiome. Science 352, 544–545 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guillemin M. N., Miles H. M., McDonald M. I., Activity of coumermycin against clinical isolates of staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29, 608–610 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emami S., Foroumadi A., Faramarzi M. A., Samadi N., Synthesis and antibacterial activity of quinolone-based compounds containing a coumarin moiety. Arch. Pharm. 341, 42–48 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damu G. L., Cui S. F., Peng X. M., Wen Q. M., Cai G. X., Zhou C. H., Synthesis and bioactive evaluation of a novel series of coumarinazoles. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 3605–3608 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venkatesan N., Perumal G., Doble M., Bacterial resistance in biofilm-associated bacteria. Future Microbiol. 10, 1743–1750 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma D., Misba L., Khan A. U., Antibiotics versus biofilm: An emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 8, 76 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kloosterman T. G., Kuipers O. P., Regulation of arginine acquisition and virulence gene expression in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae by transcription regulators ArgR1 and AhrC. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 44594–44605 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulz C., Gierok P., Petruschka L., Lalk M., Mader U., Hammerschmidt S., Regulation of the arginine deiminase system by ArgR2 interferes with arginine metabolism and fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae. MBio 5, e01858-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larsen R., Kok J., Kuipers O. P., Interaction between ArgR and AhrC controls regulation of arginine metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19319–19330 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Martino M. L., Campilongo R., Casalino M., Micheli G., Colonna B., Prosseda G., Polyamines: Emerging players in bacteria-host interactions. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 484–491 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thurlow L. R., Joshi G. S., Clark J. R., Spontak J. S., Neely C. J., Maile R., Richardson A. R., Functional modularity of the arginine catabolic mobile element contributes to the success of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe 13, 100–107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J., Sperandio V., Frantz D. E., Longgood J., Camilli A., Phillips M. A., Michael A. J., An alternative polyamine biosynthetic pathway is widespread in bacteria and essential for biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9899–9907 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cardile A. P., Woodbury R. L., Sanchez C. J. Jr., Becerra S. C., Garcia R. A., Mende K., Wenke J. C., Akers K. S., Activity of norspermidine on bacterial biofilms of multidrug-resistant clinical isolates associated with persistent extremity wound infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 973, 53–70 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hobley L., Li B., Wood J. L., Kim S. H., Naidoo J., Ferreira A. S., Khomutov M., Khomutov A., Stanley-Wall N. R., Michael A. J., Spermidine promotes Bacillus subtilis biofilm formation by activating expression of the matrix regulators lrR. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 12041–12053 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/30/eaay9597/DC1