Abstract

Objective

To examine whether mental health problems predict incident use of 12 different tobacco products in a nationally representative sample of youth and young adults.

Method

This study analyzed Wave (W) 1 and W2 data from 10,533 12–24-year old W1 never tobacco users in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Self-reported lifetime internalizing and externalizing symptoms were assessed at W1. Past 12-month use of cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe, hookah, snus pouches, other smokeless tobacco, bidis and kreteks (youth only), and dissolvable tobacco was assessed at W2.

Results

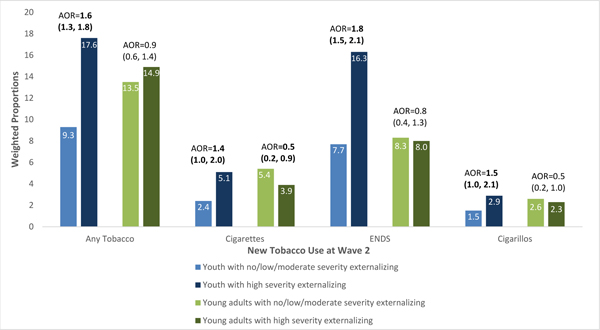

In multivariable regression analyses, high severity W1 internalizing (adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=1.5, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.3, 1.8) and externalizing (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 1.1, 1.5) problems predicted W2 onset of any tobacco use compared to no/low/moderate severity. High severity W1 internalizing problems predicted W2 use onset across most tobacco products. High severity W1 externalizing problems predicted onset of any tobacco (AOR=1.6, 95% CI: 1.3, 1.8), cigarettes (AOR=1.4, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.0), ENDS (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.5, 2.1), and cigarillos (AOR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.1) among youth only.

Conclusions

Internalizing and externalizing problems predicted onset of any tobacco use. However, findings differed for internalizing and externalizing problems, and by age. In addition to screening for tobacco use, healthcare providers should consider screening for mental health problems as a predictor of tobacco use. Interventions addressing mental health problems may prevent youth from initiating tobacco use.

Keywords: adolescent, young adult, tobacco, mental health, epidemiologic studies

INTRODUCTION

While decreases in the overall prevalence of cigarette use among youth and young adults in the United States (U.S.) have been observed over the past decade, cigarette use among those with mental illness has remained static since 2005.1–3 Further, individuals with serious mental illnesses have a life expectancy 25 years shorter when compared to the general population,4 with a bulk of the disparity attributed to tobacco-related illnesses.5 The literature thus far has been limited to examination of associations between mental illness and cigarette use,5 despite increases in use of non-cigarette products, such as e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars (e.g. cigarillos), especially among U.S. youth and young adults.6 Therefore, it is critical to examine whether mental illness predicts the onset of tobacco use across products during adolescence and young adulthood, when the risk of the onset of mental illness and substance use is greatest.7, 8

Few longitudinal studies have examined how internalizing (depression, anxiety) and externalizing (conduct, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), oppositional/defiant) problems predict tobacco use among youth and young adults. Those that have examined the onset of tobacco use among individuals with mental health problems are generally limited to cigarette use among youth.8–13 While studies of internalizing problems have shown that depression predicts the onset of cigarette use among youth,8–10 others found mixed results for anxiety.11, 12 Two studies found that ADHD predicts the onset of cigarette use among youth,8, 13 and one study among youth and young adults found that ADHD plus a co-existing conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder predicted overall tobacco use in the past year.14 Additionally, higher depressive symptoms among college students predicted e-cigarette use in the past 30 days.15 However, to our knowledge, no prospective study has explored whether mental health problems predict the onset of tobacco use across products among youth and young adults.

Using data from Waves 1 and 2 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, the present study investigated whether internalizing and externalizing problems at Wave 1 predicted the onset of use for multiple types of tobacco products (i.e., 12 products for youth; 10 products for young adults) at Wave 2 in a nationally representative sample of youth and young adult never tobacco users. Based on the negative reinforcement model of drug addiction,16 we hypothesized that those with higher severity of internalizing and externalizing problems would be more likely to begin using tobacco, regardless of product type. Furthermore, because early onset of psychopathology may be a marker for future tobacco use behaviors,17 we also examined whether the association between mental health problems and tobacco use varied by age group.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This paper reports data from youth (12–17 years) and young adults (18–24 years) recruited at Wave 1 (September 2013-December 2014) and followed up approximately a year later (average period of follow-up was 52 weeks) at Wave 2 (October 2014-October 2015) of the PATH Study. The time between the interviews varied as a function of respondents’ schedules, time needed to contact respondents, and grouping of multiple respondents within a household. The present analyses were restricted to 10,533 Wave 1 youth (n=9,067) and young adult (n=1,466) never tobacco users with data on tobacco use, internalizing and externalizing problems, and covariates for the specific associations examined. Of these Wave 1 youth, 1,051 turned 18 years old at Wave 2 and were retained in the youth analyses.

Further details regarding the PATH Study design and methods are published elsewhere.18 Details on survey interview procedures, questionnaires, sampling, weighting and information on accessing the data are available at http://doi.org/10.3886/Series606. The PATH Study recruitment employed a stratified address-based, area-probability sampling design at Wave 1 that oversampled adult tobacco users, young adults (18 to 24 years), and African-American adults. An in-person screener was used at Wave 1 to select youths and adults from households for participation.

Population and replicate weights were created that adjusted for the complex study design characteristics (e.g., oversampling at Wave 1) and nonresponse at Waves 1 and 2. Combined with the use of a probability sample, the weights allow analyses of the PATH Study data to compute estimates that are robust and representative of the non-institutionalized, civilian U.S. population ages 12 years and older. At Wave 1, the weighted response rate for the household screener was 54.0%. Among households that were screened, the overall weighted response rate at Wave 1 was 74.0% for the Adult Interview and 78.4% for the Youth Interview. At Wave 2, the overall weighted response rate was 83.2% for the Adult Interview and 87.3% for the Youth Interview. The PATH Study uses audio computer-assisted self-Interviews (ACASI) available in English and Spanish to collect self-report information on tobacco-use patterns and associated health behaviors. All participants age 18 and older provided informed consent, with youth participants age 12 to 17 providing assent while their parent/legal guardian provided consent. The study was conducted by Westat and approved by the Westat institutional review board.

Measures

Mental Health Problems

Mental health problems were assessed via the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Short Screener (GAIN-SS), modified for the PATH Study.19, 20 The GAIN-SS identifies individuals at risk for mental health or substance use disorders using a continuous measure of severity, based on the number of items endorsed. Items for the GAIN-SS were derived from the full GAIN instrument, a validated, standardized biopsychosocial assessment for individuals entering treatment for substance use or mental health disorders21 and recommended for use in epidemiological samples by the PhenX Toolkit.22 This study assessed severity across two subscales: internalizing (4 items) and externalizing (7 items) problems. The items and reliability for these subscales have been reported elsewhere.19, 20

The number of responses endorsed for lifetime mental health problems were summed for each subscale and complete data for subscale components were required (range: 0–4 for internalizing problems and 0–7 for externalizing problems). Based on the number of symptoms endorsed for each of the two subscales, respectively, participants were categorized into no/low/moderate (0–3 symptoms) or high (4 symptoms for internalizing problems or ≥4 symptoms for externalizing problems) severity levels.19, 20 Categorization of an individual as high severity indicates a high likelihood of a lifetime occurrence of a disorder with need for services.23

Tobacco use

Participants were asked about past 12-month use of each tobacco product at Wave 2, including cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), traditional cigars, cigarillos, filtered cigars, pipe, hookah, smokeless tobacco (i.e. loose snus, moist snuff, dip, spit, or chewing tobacco), snus pouches, bidis and kreteks (youth only), and dissolvable tobacco. A brief description and pictures of each product (except cigarettes) were shown to participants when asked about the products. Wave 1 never tobacco users (i.e., never using any of the above listed 12 tobacco products for youth and never using any of the above listed 10 tobacco products for young adults) who reported use of a tobacco product in the past 12 months at Wave 2 were classified as new users. Due to assessment of e-cigarettes in Wave 1 and ENDS in Wave 2, new ENDS users were defined as Wave 1 never e-cigarette users who reported past 12-month ENDS use at Wave 2. In Wave 2, summary variables were created for use of the following tobacco products: any tobacco (i.e., any of the 12 (youth)/10 (young adults) tobacco products), any cigar (i.e., traditional cigars, cigarillos, or filtered cigars), and any smokeless (i.e., smokeless tobacco excluding snus pouches, snus pouches, or dissolvable tobacco). Complete data were required when defining non-use for the summary variables.

Covariates

Ever use of alcohol or any drug was assessed via participants’ responses to questions on ever use of each of the following at Wave 1: alcohol, marijuana (including blunts), misuse of prescription drugs (i.e. Ritalin® or Adderall®; painkillers, sedatives, or tranquilizers), cocaine or crack, stimulants (i.e. methamphetamine or speed), heroin, inhalants, solvents, and hallucinogens. Substance use items in the PATH Study were adapted from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions24 and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.25 Information was also collected on socio-demographics, including age (12–17, 18–24), gender (male, female), race (white only, black only, Asian only, other including multi-racial) and ethnicity (Hispanic, not Hispanic).

Statistical Analyses

Distributions of new use for each tobacco product at Wave 2, according to severity of internalizing problems and externalizing problems, respectively, at Wave 1 were examined. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the associations between lifetime internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively, and new tobacco use, adjusting for socio-demographics, and ever any substance use at Wave 1. To address the high comorbidity of these problems among youth and young adults,26 lifetime internalizing problems and externalizing problems were included in the same model for each tobacco product. Additionally, age group (i.e., youth/young adult) by lifetime internalizing problem interactions were tested (adjusted for socio-demographics, ever any substance use, and lifetime externalizing problems), and age group by lifetime externalizing problem interactions were tested (adjusted for socio-demographics, ever any substance use, and lifetime internalizing problems).

Estimates were weighted to represent the U.S. youth and young adult populations; variances and confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the balanced repeated replication (BRR) method27 with Fay’s adjustment set to 0.3 to increase estimate stability.28 Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% CIs were calculated for all regression analyses. Two-sided p-values of <.05 were considered statistically significant. When statistically significant age group interactions were identified, age group-stratified analyses were evaluated. Estimates based on fewer than 50 observations in the denominator or with a relative standard error greater than 0.30 were suppressed.29 Based on these criteria, individual estimates for pipe, bidis, kreteks, and dissolvable were suppressed in the table and figure. All analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 14.30

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of the sample have been reported elsewhere.6, 19, 20 At Wave 1, 29% of youth and young adults had high severity internalizing problems in their lifetime, while 39% had lifetime high severity externalizing problems. At Wave 2, about 13% of youth and young adult never tobacco users at Wave 1 started using any tobacco products. The most commonly used product was ENDS (10%), followed by hookah (5%) and cigarettes (4%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

New Tobacco Product Use at Wave 2 by Lifetime Severity of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems at Wave 1 among Youth and Young Adult Never Tobacco Users in the PATH Study

| Wave 1 Internalizing

problems |

Wave 1 Externalizing

problems |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New tobacco use among W1 Never users‡ | No/low/moderate severity (referent) 71.4%a | High severity 28.6%a | New tobacco use among W1 Never users‡‡ | No/low/moderate severity (referent) 60.8%a | High severity 39.2%a | |||||||||||

| New Tobacco Use between Waves 1 and 2 (Never-P12 Month Use) | Unweighted n | Weighted % (SE)b | Unweighted n | Weighted % (SE)b | Unweighted n | Weighted % (SE)b | AORc | 95% CIc | Unweighted n | Weighted % (SE)b | Unweighted n | Weighted % (SE)b | Unweighted n | Weighted % (SE)b | AORc | 95% CIc |

| Any tobacco | 1321 | 13.4 (.5392) | 764 | 11.4 (.5388) | 557 | 18.3 (1.042) | 1.49 | 1.26–1.77 | 1297 | 13.3 (.5416) | 580 | 11.0 (.5491) | 717 | 16.9 (.9287) | 1.29d | 1.07–1.54 |

| Cigarettes | 393 | 4.1 (.2336) | 206 | 3.2 (.2479) | 187 | 6.4 (.5509) | 2.23 | 1.66–3.00 | 389 | 4.1 (.2323) | 174 | 3.6 (.2797) | 215 | 4.8 (.3990) | 0.91d | 0.68–1.21 |

| ENDS | 1147 | 10.4 (.4137) | 653 | 8.7 (.4366) | 494 | 14.6 (.8438) | 1.38 | 1.15–1.66 | 1130 | 10.4 (.4165) | 477 | 8.0 (.4601) | 653 | 14.0 (.7929) | 1.40d | 1.14–1.72 |

| Any cigar | 300 | 3.4 (.2721) | 165 | 2.5 (.2543) | 135 | 5.5 (.5922) | 2.15 | 1.53–3.03 | 298 | 3.4 (.2630) | 131 | 2.8 (.2852) | 167 | 4.3 (.4313) | 0.99 | 0.72–1.37 |

| Traditional cigars | 135 | 1.8 (.1823) | 73 | 1.4 (.1703) | 62 | 2.7 (.4370) | 2.08 | 1.34–3.21 | 132 | 1.8 (.1797) | 64 | 1.6 (.1809) | 68 | 2.0 (.3382) | 0.85 | 0.53–1.34 |

| Cigarillos | 217 | 2.2 (.1878) | 126 | 1.7 (.1880) | 91 | 3.5 (.4117) | 2.03 | 1.30–3.18 | 218 | 2.3 (.1898) | 98 | 2.0 (.2447) | 120 | 2.8 (.2636) | 0.93d | 0.63–1.38 |

| Filtered cigars | 56 | 0.5 (.0797) | 25 | 0.3 (.0761) | 31 | 1.0 (.2067) | 2.61 | 1.45–4.70 | 55 | 0.5 (.0806) | 23 | 0.4 (.1007) | 32 | 0.7 (.1475) | 0.88 | 0.46–1.69 |

| Pipe | 32 | 0.3 (.0764) | 22 | 0.3 (.1003) | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | 31 | 0.3 (.0760) | ⱡ | ⱡ | 17 | 0.3 (.0812) | ⱡ | ⱡ |

| Hookah | 405 | 4.7 (.2892) | 229 | 4.1 (.3676) | 176 | 6.4 (.5342) | 1.53 | 1.10–2.11 | 395 | 4.7 (.2887) | 187 | 4.2 (.3362) | 2 08 | 5.5 (.4854) | 1.11 | 0.81–1.52 |

| Any smokeless tobaccoe | 120 | 1.1 (.1120) | 83 | 1.1 (.1434) | 37 | 1.1 (.1901) | 1.18 | 0.75 1.83 | 120 | 1.2 (.1116) | 63 | 1.1 (.1744) | 57 | 1.2 (.1827) | 0.86 | 0.53–1.37 |

| Smokeless tobacco (excluding snus pouches) | 93 | 0.9 (.1124) | 66 | 0.9 (.1377) | 27 | 0.8 (.1388) | 1.05 | 0.68 1.62 | 92 | 0.9 (.1163) | 53 | 1.0 (.1708) | 39 | 0.8 (.1372) | 0.70 | 0.43–1.13 |

| Snus pouches | 40 | 0.4 (.0532) | 25 | 0.3 (.0605) | 15 | 0.5 (.1234) | # | 39 | 0.4 (.0528) | 17 | 0.3 (.0573) | 22 | 0.5 (.1035) | # | ||

| Bidis† | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | # | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | # | ||

| Kreteks† | 15 | 0.2 (.0473) | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | 14 | 0.2 (.0457) | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ |

| Dissolvable tobacco | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | # | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | ⱡ | # | ||

Population of interest: Wave 1 youth (12–17, N=8,873) and young adults (18–24, N=1,455) who never used any tobacco at Wave 1; estimates weighted using W2 longitudinal weights

Restricted to those with Wave (W) 1 internalizing problem data

Restricted to those with W1 externalizing problem data

Percentages (%)s represent the prevalence of Wave 1 lifetime mental health problems

Percentages (%)s and standard errors (SE)s represent the prevalence of new tobacco use between W1 and W2 by W1 lifetime mental health problems

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR)s and 95% confidence intervals (CI)s indicate the odds of new tobacco use between W1 and W2 as a function of lifetime mental health problems; adjusted for age group (12–17 vs. 18–24), gender, race, ethnicity, ever any substance use at W1, and other mental health problems at W1 (i.e., internalizing problems analyses adjusted for externalizing problems, and externalizing problems analyses adjusted for internalizing problems) Statistically significant associations at p<0.05 indicated in bold text

Indicates significant age interaction at p<0.05

Includes snus pouches, smokeless tobacco excluding snus pouches, and dissolvables

Excludes those aged 17 or older at W1

Model did not run

Estimate has been suppressed because it is statistically unreliable. It is based on a (denominator) sample size of less than 50, or the coefficient of variation of the estimate (or its complement) is larger than 30 percent.

New Tobacco Product Use at Wave 2 by Lifetime Severity of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems at Wave 1 among Youth and Young Adults

Table 1 presents the unadjusted distributions of new tobacco product use at Wave 2 by lifetime severity of internalizing problems at Wave 1. In models adjusting for demographics, substance use, and externalizing problems, youth and young adults with high severity internalizing problems were 1.5 times more likely to begin using any tobacco product (95% CI: 1.3, 1.8) compared to those with no/low/moderate severity internalizing problems. Associations were significant across all tobacco products, except any smokeless tobacco and smokeless tobacco excluding snus pouches. The strongest associations were observed for new filtered cigar use (AOR=2.6, 95% CI: 1.5, 4.7) and new cigarette use (AOR=2.2, 95% CI: 1.7, 3.0). The results for pipe and kreteks were statistically unreliable, and models did not converge for snus pouches, bidis, and dissolvables. There were no significant age interactions across products.

Table 1 also presents the unadjusted distributions of new tobacco product use at Wave 2 by lifetime severity of externalizing problems at Wave 1. In adjusted models, youth and young adults with high severity externalizing problems were more likely to begin using any tobacco product (AOR=1.3, 95% CI: 1.1, 1.5). Regarding specific tobacco products, high severity externalizing problems at Wave 1 predicted only new ENDS use (AOR=1.4, 95% CI: 1.1, 1.7) at Wave 2, while other products did not reach statistical significance when examined individually. However, there were significant age interactions for any tobacco product (p=.002), cigarettes (p=.002), ENDS (p=.001), and cigarillos (p=.046); stratified results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

New Tobacco Product Use at Wave 2 by Lifetime Severity of Externalizing Problems at Wave 1 stratified by Age (i.e. youth versus young adults) in the PATH Study

Population of interest: Wave 1 youth (12–17, N=9,067) and young adults (18–24, N=1,466) who never used any tobacco at Wave 1; estimates weighted using W2 longitudinal weights

Age (i.e. youth (12–17) vs adult (18–24)) by lifetime severity externalizing problems interactions significant at p<.05.

Age-stratified data shown for proportions of new tobacco product use at Wave 2 by lifetime severity externalizing problems.

Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, ever substance use, and lifetime internalizing problems at Wave 1.

Statistically significant associations at p<0.05 indicated in bold text.

New Tobacco Product Use at Wave 2 by Lifetime Severity of Externalizing Problems at Wave 1: Age-Stratified Analyses for Significant Age Group Interactions

Figure 1 presents the unadjusted distributions of new tobacco use at Wave 2 by lifetime severity of externalizing problems at Wave 1 for the significant age (i.e. youth versus young adults) interactions. New use of any tobacco, cigarettes, ENDS, and cigarillos was more likely among youth with high severity externalizing problems than youth with no/low/moderate severity externalizing problems.

As seen in Figure 1, in adjusted models, the strongest association across products was observed for onset of ENDS among youth with high severity externalizing problems (AOR=1.8, 95% CI: 1.5, 2.1) compared to youth with no/low/moderate severity externalizing problems, followed by cigarillos (AOR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.1) and cigarettes (AOR=1.4, 95% CI: 1.0, 2.0).

DISCUSSION

Among this nationally representative sample of youth and young adult never tobacco users, internalizing and externalizing problems each independently predicted onset of any tobacco use. Associations were robust to important confounders,19, 31, 32 including substance use and comorbid mental health problems. Across tobacco products, however, findings differed for internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as by age group.

Internalizing problems predicted the onset of nearly all tobacco product use assessed among youth and young adults, thereby extending findings of prior research focused on cigarettes among youth.8–10 While our findings linking internalizing problems to tobacco use are consistent across products, prior studies have generated mixed results for internalizing problems and tobacco use associations.8–12 These differences could be due to definitional approaches used, including our assessment of mental health symptoms versus diagnoses,8, 10, 12 and collapsing depression and anxiety rather than separating as has been done in other studies. Additionally, differences in samples (e.g. clinical versus population-based) may be a factor in accounting for divergent findings. Nonetheless, the findings from this nationally representative prospective study suggest that internalizing problems are a strong signal for the onset of tobacco use across a wide range of tobacco products in both youth and young adults.

Externalizing problems similarly predicted the onset of any tobacco use among youth and young adults. However, across products, the only significant association found was for the onset of ENDS, likely driving the ‘any tobacco use’ association. One plausible interpretation is that youth and young adults with behavioral problems may be attracted to new products such as ENDS, as these individuals may be intrigued by novel stimuli and experiences. From an environmental-exposure perspective, individuals with behavioral issues may be introduced to ENDS through peers or friends who use ENDS, which are often consumed in social contexts.33 Future studies can examine whether youth and young adults with externalizing problems are more likely to start use of ENDS in comparison to other tobacco products.

Additionally, age interactions were observed for externalizing psychopathology in which youth with high severity problems were more likely to begin using cigarettes, ENDS, and cigarillos than youth classified as no/low/moderate severity. One study found that while externalizing psychopathology robustly predicted early onset of cigarette use by age 14, internalizing was a weaker predictor, perhaps because the internalizing-substance pathway emerges later in adolescence.34 Our findings that externalizing problems predicted the onset of cigarette, ENDS, and cigarillo use among youth further implicates externalizing problems among youth as risk factors for these tobacco products.

Neither internalizing nor externalizing problems were associated with any smokeless tobacco use, suggesting that youth and young adults with mental health problems are not disproportionally drawn to this class of tobacco products. The few studies that have examined the profiles of smokeless tobacco users have focused on demographic indicators. While prior studies found the most common smokeless tobacco users to be white middle-aged or older males generally of lower socioeconomic status,35, 36 a recent study found that smokeless tobacco use was most common among males, younger adults, non-Hispanic Whites, and individuals residing in nonurban areas.37 It is important to understand risk and protective factors for smokeless tobacco use, including examination of interactions between demographic and psychosocial factors, especially those that may be unique to this class of products.

This study has several important strengths, as well as some limitations. First, it is one of the first to assess the onset of tobacco use among youth and young adults as a function of internalizing and externalizing problems in a nationally representative sample. Second, this study provides a comprehensive assessment of tobacco product use, which is rapidly evolving as new products gain favor in the marketplace. Third, the study included important covariates that allow for adjustment of potential confounding, such as demographics, substance use, and comorbid mental health problems. However, some potential confounders that could impact the association between mental health problems and tobacco use were excluded, such as sensation seeking (assessed among youth but not adults in the PATH Study) and peer influence (not assessed in Waves 1 and 2 of the PATH Study). Fourth, although this study did not include diagnoses for internalizing and externalizing disorders, the high sensitivity and specificity between GAIN-SS items and psychiatric diagnoses supports the use of this measure as a strong indicator of significant mental health problems.21 Fifth, to the extent that externalizing problems are a predictor of early tobacco use,34, 38 our exclusion of Wave 1 tobacco users may have contributed to the inconsistent associations we found between externalizing and tobacco use; that is, it is possible that those with externalizing problems who had already initiated tobacco use were excluded.19, 20 When stratified by age, externalizing problems predicted the onset of cigarette, ENDS, and cigarillo use among youth, further supporting this hypothesis. Finally, while longitudinal associations were identified between mental health and tobacco use, causality cannot be determined by this epidemiologic study. Future assessments of mental health and tobacco use using additional waves of data collection in the PATH Study could help to inform our understanding of the progression of tobacco use (i.e., frequency and intensity of tobacco use, dual use, ability to stop using tobacco) among those with and without mental health problems over time.

In summary, this study demonstrates that mental health problems predict the onset of tobacco use among youth and young adults in a nationally representative sample, and across a wide range of specific tobacco products beyond cigarettes. A negative reinforcement model of drug addiction would suggest that tobacco use is initiated to ameliorate mental distress, but we cannot rule out that these associations are potentially driven by a common underlying factor of environmental, familial, or genetic risk for both mental illness and tobacco use.5, 20 In addition to screening for tobacco use, it would be helpful if healthcare providers considered screening for mental health problems as a tool to detect tobacco product use onset. Researchers can continue to investigate internalizing and externalizing problems as potential etiologic factors for the onset of tobacco use.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Kathryn C. Edwards, PhD and Kevin C. Frissell, PhD of Westat for their assistance with deriving the variables and Dr. Kevin C. Frissell, PhD of Westat for completing quality control reanalyses. This article was prepared while Dr.Kevin P. Conway was employed at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and Drs. Amy Cohn and Raymond S. Niaura were employed at the Schroeder Institute for Tobacco Research and Policy Studies, Truth Initiative, Washington, DC.

Disclosures:

Dr. Cummings has received grant support from Pfizer and fees as a paid expert witness in litigation filed against the tobacco industry.

Dr. Compton has declared ownership of stock in General Electric Co., 3M Co., and Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Drs. Conway, Silveira, Cohn, Stanton, Callahan-Lyon, Sargent, Niaura, Reissig, Zandberg, Brunette, Tanski, Borek, Hyland, and Mss. Green, Kasza, Slavit, Hilmi, Lambert report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views, official policy or position of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its affiliated institutions or agencies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steinberg ML, Williams JM, Li Y. Poor Mental Health and Reduced Decline in Smoking Prevalence. Am J Prev Med. September 2015;49(3):362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence D, Williams JM. Trends in Smoking Rates by Level of Psychological DistressTime Series Analysis of US National Health Interview Survey Data 1997–2014. Nicotine Tob Res. December 24 2015;18(6):1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME, Mauer B. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) Medical Directors Council;2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeHay T, Morris C, May MG, Devine K, Waxmonsky J. Tobacco use in youth with mental illnesses. J Behav Med. April 2012;35(2):139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-Product Use by Adults and Youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. January 26 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance A, Mental Health Services A, Office of the Surgeon G. Reports of the Surgeon General Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hockenberry JM, Timmons EJ, Weg MW. Adolescent mental health as a risk factor for adolescent smoking onset. Adolesc Health Med Ther. February/27 2011;2:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein SM, Mermelstein R, Shiffman S, Flay B. Mood variability and cigarette smoking escalation among adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav. December 2008;22(4):504–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Wagner EF. Cigarette smoking, major depression, and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. December 1996;35(12):1602–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moylan S, Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Berk M. Cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of population-based, epidemiological studies. BMC Med. October 19 2012;10(1):123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. Nov 8 2000;284(18):2348–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. January 1997;36(1):37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symmes A, Winters KC, Fahnhorst T, et al. The Association Between Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Nicotine Use Among Adolescents and Young Adults. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 11/10 2015;24(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandiera FC, Loukas A, Li X, Wilkinson AV, Perry CL. Depressive Symptoms Predict Current E-Cigarette Use Among College Students in Texas. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2017;ntx014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Plasticity of reward neurocircuitry and the ‘dark side’ of drug addiction. Nature neuroscience. November 2005;8(11):1442–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 12//print 2008;9(12):947–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tob Control. August 08 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, et al. Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among adults: Findings from Wave 1 (2013–2014) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. May 30 2017;177:104–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, et al. Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among youth: Findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addict Behav. August 18 2017;76:208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennis ML, Chan YF, Funk RR. Development and validation of the GAIN Short Screener (GSS) for internalizing, externalizing and substance use disorders and crime/violence problems among adolescents and adults. Am J Addict. 2006;15 Suppl 1:80–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol. August 1 2011;174(3):253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennis M, Feeney T, Stevens L, Bedoya L. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs–Short Screener (GAIN-SS): Administration and Scoring Manual for the GAIN-SS Version 2.0.3 Vol http://www.chestnut.org/LI/gain/GAIN_SS/index.html. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Instiutes of Health (NIH). National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). In: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), ed. Rockville, MD.; 2004-2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Questionnaire (NHANES). In: National Center for Health Statistics, ed. Hyattsville, MD,; 2011-2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. January 1999;40(1):57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy PJ. Pseudoreplication: further evaluation and applications of the balanced halfsample technique. Vital Health Stat 2. January 1969(31):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Judkins DR. Fay’s method for variance estimation. J. Off. Stat. 1990;6:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein RJ, Proctor SE, Boudreault MA, Turczyn KM. Healthy People 2010 criteria for data suppression. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; June 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stata statistical software: Release 12 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, et al. Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among youth: Findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addict Behav. January 2018;76:208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US);2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kong G, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Palmer A, Morean M, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for E-cigarette initiation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1/1/ 2015;146:e162–e163. [Google Scholar]

- 34.King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agaku IT, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Vardavas CI, Alpert HR, Connolly GN. Use of Conventional and Novel Smokeless Tobacco Products Among US Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e578–e586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timberlake DS, Huh J. Demographic Profiles of Smokeless Tobacco Users in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 7// 2009;37(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng YC, Rostron BL, Day HR, et al. Patterns of Use of Smokeless Tobacco in US Adults, 2013–2014. Am J Public Health. September 2017;107(9):1508–1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olson SL, Sameroff A, Lunkenheimer ES, Kerr D. Self-regulatory processes in the development of disruptive behavior problems: The preschool-to-school transition. Biopsychosocial regulatory processes in the development of childhood behavioral problems. 2009;13:144–185. [Google Scholar]