Abstract

Background

The recent interest in defining and theorizing social determinants of health has illuminated the importance of culture as a central phenomenon of interest. However, cultural processes appear in multiple places in social determinants of models, and their specifics are not delineated or operationalized.

Objectives

This theory development paper describes the complexity of defining cultural variables, and uses medical anthropology to demonstrate how cultural domains, constructs, and variables can be defined.

Methods

Using cultural anthropology theory, empirical work, and a literature synthesis as a starting point, the evolution of the cultural determinants of help seeking (CDHS) theory is explored, and the revision of the theory is highlighted.

Results

The expanded theory included structural concepts as control variables, reframes illness as “suffering,” and adds concepts, of course, cure, manageability, meaning in life, functioning, social negativity, and perceived need.

Discussion

Strategies for and benefits of isolating and operationalizing cultural variables for middle-range theory development and testing are discussed.

Keywords: cultural anthropology, mixed-methods research, nursing theory, social determinants of health

The U.S. National Institutes of Health have recommended new approaches to improve the precision, accuracy, and efficiency of the measurement of behavioral and social phenomena, and their contexts, that impact health outcomes. (Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, 2017). This call is part of a larger global health equity movement, perhaps best articulated by the Global Commission on the Social Determinants of Health in 2005 to foster global policies that would reduce inequities (Marmot, Allen, Bell, Bloomer, & Goldblatt, 2012). Social determinants of health is defined as the wider set of political, economic and environmental circumstances, forces, and systems that shape the conditions of daily life (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016). The social determinants of health model summarizes how social structure—influenced by cultural and political-economic forces—affects population health and might be considered a philosophical perspective or a value-based “lens” through which policymakers and service providers should understand health and healthcare (Starfield, 2007).

The cultural concepts within the social determinants of health model differ in their readiness for operationalization for research. Cultural beliefs, values, and practices are sometimes cast as broad ideological and philosophical frameworks that interact with or support other macro-level institutions, but also as intermediary-level cultural beliefs, values, and practices that shape social interactions. The placement of “culture” at both the system and the intermediary level is problematic for theory building and testing. This paper focuses on the cultural components of the social determinants of health models—helping the reader make sense of the complexity of culture within the larger social determinants of health enterprise—and demonstrates the process of theorizing culture from the perspective of medical anthropology.

The focus on the cultural and social aspects of the social determinants of health are of particular interest for nursing research, which explicitly seeks to understand how health, healthcare, and health behavior are multidetermined, and the impact of this on nursing research conduct (Holden & Littlewood, 2015; Leininger & McFarland, 2006; Peña, 2007; Poss, 2001). Nursing research has an interest in the ways that individuals, families, communities, and healthcare systems derive meaning, and sustain (or abandon) cultural traditions, recognizing them as critical to understanding and influencing health and health behavior. Moreover, cultural humility requires meaningful engagement with people where they are, incorporating their perspectives, values, and preferences (Hook, Davis, Owen, Worthington, & Utsey, 2013; Isaacson, 2014; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). Increasingly, nursing research is charged to be clear about their definitions and operationalization of cultural variables that affect health and healthcare.

Cultural Determinants of Health

The cultural aspects of the social determinants of health might be defined as, “cultural determinants of health” understanding that they interact with other structural aspects of society, exert influence at the community as well as the personal levels. A search of PubMed using “cultural determinants” as a keyword yields 60 citations and “cultural determinants” in the body yields 260 citations. The phrase references the importance of, or attention to, beliefs, values, social organization, and practices that are influenced by culture, and in turn, influence health behavior, healthcare utilization, or help seeking. Since defining culture in the social determinants of health has been elusive, we define cultural determinants of health as “the interacting ideological, socioeconomic and practice level processes that influence health-related perceptions, categorizations, and behaviors.”

Medical Anthropological Contributions

To understand the complexity of delineating cultural concepts for theory development, we will examine how medical anthropology has theorized culture in health and healing. Medical anthropology is a disciplinary perspective within the broader field of anthropology, with a focus on those social and cultural factors that influence health and well-being, the experience of illness and healing processes, sociocultural and institutional efforts to prevent and treat sickness, social relations that influence therapeutic interventions, and the cultural importance and utilization of pluralistic medical systems (Society for Medical Anthropology, 2017). Major anthropological domains of inquiry—including how major constructs that are explored in medical anthropology by key authors in the fields—are briefly summarized in Table 1. Further, a sampling of the research questions that might be studied, concepts that can be operationalized, and how concepts of the middle range theory cultural determinants of help seeking (CDHS) were operationalized are provided.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Constructs and Concepts from Medical Anthropology and the Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking Model

| Field of study/constructs | MA questions/concepts | CDHS conceptsa |

|---|---|---|

| Ideationb–f Ideals, values, meanings What is important, preferred, good, right, normal The world, our place within it |

How do beliefs/values about health and concepts about the body influence health behavior? Health-related beliefs, meanings, causal models, values, use of symbols of vocabulary, schemas |

Perception, labeling of symptoms Beliefs: cause, course, cure, manageability Social significance or consequence of illness Beliefs about functioning Perceived need |

| Politics/economicsg–i Organization of social structures Acquistion, distribution of wealth, resources Patterns of consumption, exchange Material culture, technology, infrastructre Policy Institutional, social control |

How do ideologies shape service delivery, service use, inequities and disparities, and power within the health care system? Medical or nursing education that systematically leads to inequity, discriminatory or biased practices, the evolution and justification of dominant and action, models of health care, how systems of power are upheld, perceived discrimination, stigma, and social regulation of resources and exchange |

Availability and use of social and professional services Social exchange rules |

| Practicej–q Body: nexus of practical engagements with world Tradition upholds, emobdies, enforces practices Tradition, dress, gender relations, childrearing, socialization, etiquette, communication, foods and nutrition |

How are health-related actions guided by interpretation? How do symbols function in healing diagnosis and rituals? How are system-level variables (e.g., race, class, gender, power) “performed” and embodied? Idioms of distress, health communication practices and preferences, self-disclosure, illness and health maintenance practices, and help seeking behaviors |

Help seeking actions Communication of distress within the exchange rules Embodiment of distress Health-related actions, traditions and practices |

Note. CDHS = cultural determinants of help seeking; MA = medical anthropology.

Original and revised.

Geertz (2016).

Turner, Abercrombie, & Hill (2015).

Bourdieu (1990, 2012).

Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking Theory

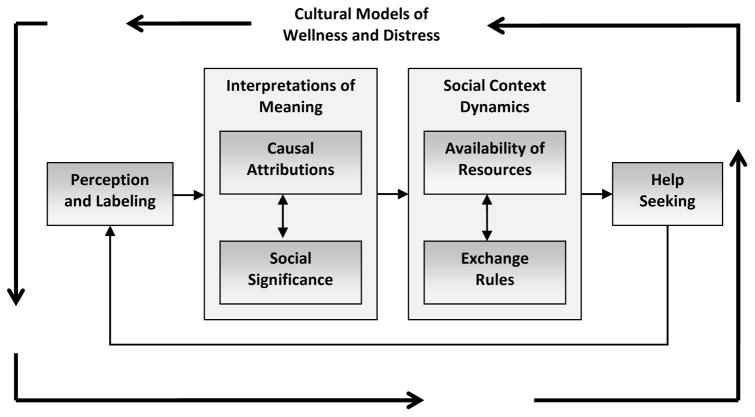

Cultural determinants of help seeking theory (Figure 1) (Saint Arnault, 2009) was developed through a synthesis of fieldwork, qualitative interviewing, and grounded theory analysis with Japanese immigrants, combined with existing literature from medical anthropology, transcultural psychiatry, cross-cultural psychology, and transcultural nursing. While the initial tests of the model were with Japanese women in an NIMH RO1 grant (MH071307) (Saint Arnault & Fetters, 2011), the goal is to identify the critical concepts across cultures for a middle-range theory of culture and help seeking that can guide intervention. Therefore, we presume CDHS concepts are transcultural, but the specific operationalization of the concepts must be culturally specific. In the original theory, help seeking was defined as, “attempts to maximize wellness or to ameliorate, mitigate, or eliminate distress” (Saint Arnault, 2009, p. 260). The original CDHS model proposed that help-seeking processes begin when there is a perception of abnormal physical or emotional sensations. Once signs of distress are experienced and labeled, people interpret their causes and their social significance. Next, people evaluate the rules that govern accessing the exchange of resources available within their social networks.

FIGURE 1.

Cultural determinants of help seeking model (Saint Arnault, D.M. (2009). Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking: A theoretical model for research and practice. Theory for Research and Practice, 23, 259–278.). Used with permission.

Theory testing

Studies used to test, revise, and expand the CDHS theory are summarized in Table 2. Qualitative studies were used to refine or explicate the nature of the help-seeking process, thereby confirming concepts, expanding concepts, and understanding the dynamic interactions among hypothesized variables. We learned that help seeking in a social context involved both social support and social negativity (Saint Arnault, 2002; Saint Arnault & Roles, 2012; Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, 2016). The meaning of distress and help seeking involves personal goals or meaning in life, as well as the implications of symptoms of distress on one’s level of functioning (Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, 2016). We also discovered that both degrees of distress, as well as an overall assessment of perceived need (Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, 2016), are interacting variables.

TABLE 2.

Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking Studies and Findings

| Study

|

Sample

|

Variables | Key findings | CDHS implications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Approach | Description | N | |||

| 2002a | Qualitative | Japanese women | 25 | Communication of distress Social context Social exchange rules Help seeking |

Help seeking influenced by: Polite hesitation (enryo) Fear: burdening others Mutual responsibility, obligations Restraint from social context |

Social exchange rules, customs Add social conflict Consider social status |

| 2006b | Quantitative | Japanese students | 50 | Symptom experience | Depression related to 26 somatic symptoms | Symptom type is important |

| US students | 44 | Depression related to joint pain only | ||||

| 2008c | Quantitative | Japanese students | 50 | Symptom experience | Depressed students from both group endorsed more than 20 physical symptoms | Physical symptoms vary by culture |

| Korean students | 61 | Only 11 were common between the groups | Idioms of distress is critical | |||

| 2008d | Qualitative | Japanese women living in US, highly stressed | 24 | Symptom experience Communication of distress Social context |

Internal pressures occurred within a social context that included both social support and social negativity Worries about responses from others |

Internal expectations of self Social significance is anticipated response from others Social negativity is as important as social support |

| 2016e | Mixed | Japanese women living in US | 209 | Symptom interpretation Causal models |

Distress “caused by internal failure” Interpretations of manageability and expectations for functioning Physical symptoms related to social stress |

Add: Overall meaning in life Manageability Functioning |

| Highly distressed subsample | 24 | |||||

| 2016f | Mixed | Irish domestic violence survivors | 21 | Symptom experience Internal help seeking barriers |

Causal beliefs (shame) interacted with social negativity to foster sense of immobilization Belief that recovery was “hopeless” associated with more physical symptoms Belief that symptoms would leave on their own associated with higher physical symptoms All but one had “frozen” feeling |

Expand beliefs about curability Include expectations of suffering course |

| 2017g | Quantitative | South Korean women | 402 | Perceived need Help seeking |

Positive correlation between perceived need and help seeking for formal mental health help | Perceived need is important variable |

| 2017h | Quantitative | Japanese women in US | 209 | Symptom experience Illness interpretation Perceived need Help seeking type |

Having physical symptoms was associated not seeking help Physical symptoms predicted perceived need |

Symptom type relates to perceived need and help seeking type Specific beliefs relate to help seeking Symptom type relates to perceived need and help seeking type |

Note. CDHS = cultural determinants of help seeking.

We used quantitative studies to examine whether and how operationalized variables were related. We found that distress type is an important aspect of suffering (Saint Arnault, Sakamoto, & Moriwaki, 2006), that physical symptoms vary by culture group (Saint Arnault & Kim, 2008), and physical symptoms are related to social stress (Saint Arnault and Shimabukuro, 2016). We also found that symptoms, social support, social conflict, or sense of coherence were not related to perceived structural barriers (such as inconvenience, availability, information, financial barriers, and satisfaction). However, physical symptoms were related to suffering interpretations (Saint Arnault & O’Halloran, 2016). We also found that physical symptoms were related to social stress (Saint Arnault & Shimabukuro, 2016), one’s perception of need, not seeking help, and professional medical help seeking (Saint Arnault & Woo, 2017).

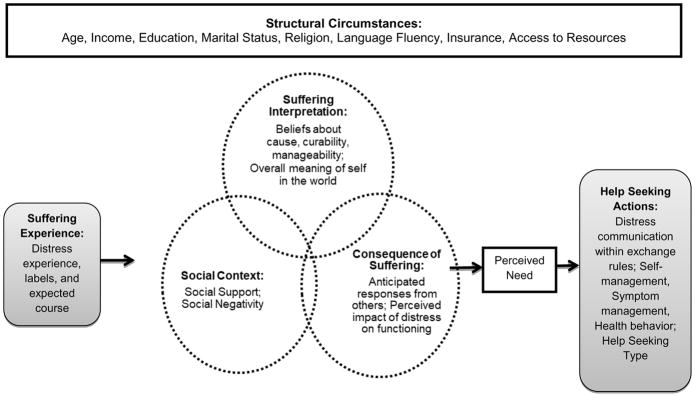

Theory expansion

We revised the CDHS model to reflect these findings (see Figure 2). Table 3 summarizes the revisions and expansions to the original CDHS model. Our definition of help seeking has become, “the experiences, expectations, and interpretations that interact with structural variables, as well as context, to influence behavior aimed at reducing suffering and promoting health.” Structural variables are included in our new theory as control variables and include such things as access, language, insurance, poverty, discrimination experiences, the length of time in the country, and adoption of the host culture’s values (Dean, Williams, & Fenton, 2013). We have shifted the focus from “illness” to “suffering” to center-stage the person within the culture, and to reduce reliance on illness categories. The sufferer—within a culturally informed context and interpretative gestalt—seeks to name and understand their suffering. Interpretations and meaning are at the heart of the theory, and we now understand that the sufferer labels experiences using culturally relevant terms or symbols, but these also contain expectations about its course. We consider the suffering experience to be a holistic phenomenon, using physical and emotional indices to capture them. “Suffering interpretations” are now understood to include beliefs about the cause, but also beliefs about cure and manageability of the experience. This interpretation is also influenced by one’s overall expectations about themselves in the world. We expanded and refined “suffering consequences” to include not only anticipated responses from others, but also expectations of the impact of the suffering on one’s ability to function. Finally, all of this is experienced within a culturally constructed contextual world, which includes available supports as well as social conflicts, burdens, and constraint. These processes culminate in a summative assessment of perceived need, and perceived need drives a variety of help-seeking choices and actions.

FIGURE 2.

Cultural determinants of help seeking model-revised.

TABLE 3.

Summary of Revisions to the Cultural Determinants of Health Seeking Model

| Construct | Original concept | Revised/expanded concept |

|---|---|---|

| Experience | Perceptions and meaning | Suffering experience |

| Labels; expected course | ||

| Meaning | Interpretations of meaning | Suffering interpretations |

| Causal attributions | Beliefs about cause, curability, manageability | |

| Overall meaning of self in the world | ||

| Social significance | Consequences of suffering | |

| Anticipated responses from others | ||

| Perception of impact of suffering on functioning | ||

| Social context | Social context dynamics | Social context |

| Availability of resources | Social support | |

| Exchange rules | Social conflict | |

| Perception of need | Perceived need | |

| Help seeking | Help seeking | Distress communication within exchange rules |

| Self-management | ||

| Symptom management | ||

| Health behavior | ||

| Help seeking type |

Discussion

The anthropological perspectives help us define and theorize relationships among cultural variables, structural variables, and health outcomes. This delineation is critical to theory development and testing. However, substantial work remains to create and test middle-range theories that can be used to guide culturally sensitive interventions and predict health-related outcomes. This work represents a nascent entry into the substantial and critically needed research enterprise, but work is fundamental to the goals of many nursing researchers.

“Culture” is often broadly construed as affiliation or self-declared identification with an ethnic group (Alegria et al., 2004). However, from a cultural determinant of health perspective, the sheer enormity of variability between and within-culture differences in suffering descriptions, interpretations, and consequences makes understanding the meaning of these cultural affiliations daunting. One important example variable is acculturation. A recent meta-analysis found that acculturation and enculturation were predictors of help-seeking attitudes (Sun, Hoyt, Brockberg, Lam, & Tiwari, 2016). While studies have shown that Asian immigrant women have the lowest overall service utilization rates of any group in the U.S. (Garland et al., 2005; Williams, 2002), the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) found that depression rates for first-generation Asian women may increase the longer women live in the US (Takeuchi, Hong, Gile, & Alegría, 2007; Takeuchi, Zane, et al., 2007). Also, the NLAAS found that even second-generation Asians—who may be familiar with Western models of treatment—did not have a greater willingness to seek help (Mojtabai et al., 2011). This limited set of studies shows the complexity of length of stay of immigrants in only one group, demonstrating that measuring acculturation and enculturation is critical.

The importance of suffering description is a critical cultural determinant of health and help seeking. Understanding “idioms of distress” is key to examining the sufferer’s experience. An idiom of distress is a collection of physical, emotional, and interpersonal sensations and experiences labeled by the individual as optimal or abnormal, and identified as important (Parsons & Wakeley, 1991; Saint Arnault & Kim, 2008). Researchers should assess the full range of symptom experiences for their populations. Recent interest in the importance of symptom experience and symptom clusters acknowledges this critical role in self-care and healthcare (Kim, Abraham, & Malone, 2013; Miaskowski, Dodd, & Lee, 2004). While diversity in idioms of distress is widely acknowledged as an important concept in self-management, much research on symptom and self-management ignores this important cultural frame. Analyses such as ours place culturally based perceptions and expectations at the center of research, potentially unveiling the culturally based roots of symptom experience and related management.

Perceptions about meaning in life, life satisfaction, quality of life, and purpose of life rest within culturally informed models of what constitutes health, wellness, and functioning. Examination of the suffering consequence construct can help us understand related evaluations such as perceived need and service utilization. It can also help us to understand how people situate themselves and their distress in the “eyes” of their communities. Failure to meet community-held expectations of functioning and health are at the heart of shame, embarrassment, and stigma. The more we understand how these are held within the sociocultural lives of the people we serve, the more we will understand how to motivate and enable them, and promote their engagement in health behaviors.

Cultural ideation influences perceptions of virtue, strength, ideal body image, or behavioral ideals. Identifying these concepts allows us to explore how praxis enforces those ideals in daily life, and how this, in turn, promotes or discourages engagement in health-related decisions and behaviors. It is within that set of expectations that people decide whether they are meeting the other’s expectations as well as those they have for themselves. These are cultural aspects of meaning that are easily overlooked but are critical for understanding help seeking.

Limitations and Conclusions

This research focused on only some groups of East Asian women, but aimed for diversity by including students, immigrants, and women living in their native countries. I recognize that this sampling limits the generalizability of the theory. Empirical research on the theory will require many more samples from diverse communities, differing levels of acculturation, male and female samples, and a host of further testing to continue to modify and enhance our understanding. However, it is essential for nursing research that we make efforts to define and delineate our cultural variables. This research is a stride toward this goal. Because culture is extremely complicated and dynamic, I recognize that research can never truly isolate, categorize, or define cultural factors. This difficulty is a central problem in most social science research, since humans are simultaneously influencing, and are influenced by, their sociocultural worlds. Still, the goal of examining relationships among various cultural and structural variables moves us closer to understanding these dynamics. The goal is to attend to the CDHS with an eye to a middle-range theory building that can contribute to nursing science and nursing care. In the end, I believe that this analysis is hopeful, illustrating that culture can be isolated and interactions between culture and other structural variables can be discerned.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges a portion of this research was funded by the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences, the Office of Women’s Health, and the National Institute of Mental Health under grant number MH071307.

Footnotes

The author has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Abercrombie N, Hill S, Turner BS, editors. Dominant ideologies (RLE social theory) London, UK: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng XL, … Woo M. Considering context, place and culture: The National Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger PL, Luckmann T. Modernity, pluralism and the crisis of meaning: The orientation of modern man. Gütersloh, Germany: Bertelsmann Foundation Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The logic of practice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Habitus. In: Hillier J, Rooksby E, editors. Habitus: A sense of place. Farnham, UK: Ashgate; 2005. pp. 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrade RG. Schemas and motivation. In: D’Andrade RG, Strauss C, editors. Human motives and cultural models. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dean HD, Williams KM, Fenton KA. From theory to action: Applying social determinants of health to public health practice. Public Health Reports. 2013;128:1–4. doi: 10.1177/00333549131286S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Chene M. Symbolic anthropology. In: Levinson D, Ember M, editors. Encyclopedia of cultural anthropology. New York, NY: Holt; 1996. pp. 1274–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Dirks N, Eley G, Ortner SB. Culture/power/history: A reader in contemporary social theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Pantheon Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geertz C. Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. London, UK: Fontana Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard C. Cultural values and ‘cultural scripts’ of Malay (Bahasa Melayu) Journal of Pragmatics. 1997;27:183–201. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(96)00032-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard C. Cultural scripts. In: Senft G, Östman J-O, Verschueren J, editors. Culture and language use. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins; 2009. pp. 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Godelier M. Anthropologie et économie: Une anthropologie économique est-elle possible? [Anthropology and Economics: Is Economic Anthropology Possible ] In: Godelier M, editor. Un domaine conteste: L’anthropologie économique [One Challenging area: Economic Anthropology] Paris, France: Mouton; 1974. pp. 285–345. [Google Scholar]

- Good BY, DelVecchio-Good M-J. “Learning medicine”: The constructing of medical knowledge at Harvard Medical School. In: Lindenbaum S, Lock M, editors. Knowledge, power and practice:The anthropology of medicine and everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1993. pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn RA, Inhorn MC. Anthropology and public health: Bridging differences in culture and society. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Bose NK, Klass M, Mencher JP, Oberg K, Opler MK, … Vayda AP. The cultural ecology of India’s sacred cattle [and comments and replies] Current Anthropology. 1966;7:51–66. doi: 10.1086/200662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holden P, Littlewood J, editors. Anthropology and nursing. London, UK: Routledge, Taylor & Francis; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, Worthington EL, Utsey SO. Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60:353–366. doi: 10.1037/a0032595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson M. Clarifying concepts: Cultural humility or competency. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2014;30:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Abraham I, Malone PS. Analytical methods and issues for symptom cluster research in oncology. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care. 2013;7:45–53. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32835bf28b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger MM, McFarland MR. Culture care diversity & universality: A worldwide nursing theory. 2. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbaum S, Lock M, editors. Knowledge, power and practice: The anthropology of medicine and everyday life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz CA. Unnatural emotions: Everyday sentiments on a Micronesian atoll and their challenge to Western theory. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380:1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K. Symptom clusters: The new frontier in symptom management research. JNCI Monographs. 2004;32:17–21. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, Jin R, Druss B, Wang PS, … Kessler RC. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1751–1761. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Strategic plan. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20745. Retrieved from https://obssr.od.nih.gov/about-us/strategic-plan/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parsons CDF, Wakeley P. Idioms of distress: Somatic responses to distress in everyday life. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1991;15:111–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00050830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED. Lost in translation: Methodological considerations in cross-cultural research. Child Development. 2007;78:1255–1264. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss JE. Developing a new model for cross-cultural research: Synthesizing the health belief model and the theory of reasoned action. Advances in Nursing Science. 2001;23:1–15. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. Help-seeking and social support in Japanese sojourners. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24:295–306. doi: 10.1177/01939450222045914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM. Cultural determinants of help seeking: A model for reseach and practice. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2009;23:259–278. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Fetters MD. RO1 Funding for mixed-methods research: Lessons learned from the mixed-method analysis of Japanese Depression Project. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2011;5:309–329. doi: 10.1177/1558689811416481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Kim O. Is there an Asian idiom of distress? Somatic symptoms in female Japanese and Korean students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2008;22:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, O’Halloran S. Using mixed methods to understand the healing trajectory for rural Irish women years after leaving abuse. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2016;21:369–383. doi: 10.1177/1744987116649636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Roles DJ. Social networks and the maintenance of conformity: Japanese sojourner women. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health. 2012;5:77–93. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2011.554030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Sakamoto S, Moriwaki A. Somatic and depressive symptoms in female Japanese and American students: A preliminary investigation. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2006;43:275–286. doi: 10.1177/1363461506064867. doi:10.1177%2F1363461506064867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Shimabukuro S. Floating on air: Fulfillment and self-in-context for distressed Japanese women. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2016;38:572–595. doi: 10.1177/0193945915625219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Woo S. Cultural barriers to help seeking despite perceived need: Japanese women living in America. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.07.006. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault DM, Woo S, Gang M. Factors influencing on mental health help-seeking behavior among Korean women: A path analysis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.10.003. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Baer H. Critical medical anthropology. Amityville, NY: Baywood; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Society for Medical Anthropology. What Is Medical Anthropology? 2017 Retrieved from http://www.medanthro.net/about/about-medical-anthropology/

- Starfield B. Pathways of influence on equity in health. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1355–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Hoyt WT, Brockberg D, Lam J, Tiwari D. Acculturation and enculturation as predictors of psychological help-seeking attitudes (HSAs) among racial and ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016;63:617–632. doi: 10.1037/cou0000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Gile K, Alegría M. Developmental contexts and mental disorders among Asian Americans. Research in Human Development. 2007;1:49–69. doi: 10.1080/15427600701480998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, Chae DH, Gong F, Gee GC, … Alegría M. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:84–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9:117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. 2016 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/

- Williams DR. Racial/ethnic variations in women’s health: The social embeddedness of health. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:588–597. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]