Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to explore the effect of antiretroviral treatment (ART) history on clinical characteristics of patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 20 patients with laboratory-confirmed co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV in a designated hospital. Patients were divided into medicine group (n = 12) and non-medicine group (n = 8) according to previous ART history before SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

The median age was 46.5 years and 15 (75%) were female. Ten patients had initial negative RT-PCR on admission, 5 of which had normal CT appearance and 4 were asymptomatic. Lymphocytes were low in 9 patients (45%), CD4 cell count and CD4/CD8 were low in all patients. The predominant CT features in 19 patients were multiple (42%) ground-glass opacities (58%) and consolidations (32%). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in the medicine group was significantly lower than that in the non-medicine group [median (interquartile range, IQR):14.0 (10.0–34.0) vs. 51.0 (35.8–62.0), P = 0.005]. Nineteen patients (95%) were discharged with a median hospital stay of 30 days (IQR, 26–30).

Conclusions

Most patients with SARS-CoV-2 and HIV co-infection exhibited mild to moderate symptoms. The milder extent of inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 infection might be associated with a previous history of ART in HIV-infected patients.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019, HIV, antiretroviral therapy, characteristics, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, serum antibodies

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was caused by a type of beta coronavirus (Zhou et al., 2020), named as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) on February 11, 2020. The disease quickly spread across China and beyond. As of July 31, 2020, over 17.1 million confirmed cases including 668,910deaths were reported worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020a). At present, the diagnosis depends on reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or gene sequencing from throat swab, sputum, or lower respiratory tract secretion (Li et al., 2020). With the false-negative results of PCR by insufficient sampling or low viral load (Zhang et al., 2020), specific antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 can be helpful to the diagnosis.

The respiratory system is one of the most frequently affected organ systems in HIV-infected patients (Benito et al., 2012). HIV patients with immunocompromised status seem to be more susceptible to viral infection than healthy individuals. Several reports on co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV have been published, therefore the public had some initial understanding about the clinical manifestation of this population (Blanco et al., 2020, Gervasoni et al., 2020, Harter et al., 2020, Maggiolo et al., 2020, Vizcarra et al., 2020, Zhu et al., 2020). It remains controversial whether HIV patients are at higher risk of severe disease or death (Gervasoni et al., 2020, Maggiolo et al., 2020).

The aim of this retrospective study was to report the clinical characteristics of a case series of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 co-infected patients in Wuhan, and to explore the effect of previous antiretroviral therapy (ART) before SARS-CoV-2 infection on clinical manifestation.

Methods

Study design and participants

Between February 25, and April 4, 2020, we have retrospectively reviewed 20 patients with laboratory-confirmed co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV from Jinyintan hospital, a designated hospital specializing in infectious diseases. All patients included were diagnosed with COVID-19 according to the interim guidance from the World Health Organization and the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 (seventh edition) published by China National Health Commission (General Office of the National Health Committee of China, 2020a, World Health Organization, 2020b). The IgM and IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were also tested on admission. One patient with negative RT-PCR but positive IgM and IgG, as well as another patient with typical symptoms (fever and cough) lasting for 29 days and a positive IgG result were diagnosed according to the seventh edition of China National Health Commission guidelines.

Demographics and epidemiological data, symptoms and signs, laboratory results, medical treatment of HIV infection before admission, as well as COVID-19 treatment and outcome data were obtained from the electronic medical records of the patients. The clinical endpoint in this study was death or discharge. The severity of the disease was classified into 2 categories (non-severe and severe) at the time of admission as used in a previous study published by China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19 (Guan et al., 2020). Patients were discharged from hospital once the results of RT-PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 turned negative for two times (at least 24 hours apart) (General Office of the National Health Committee of China, 2020a).

Imaging acquisition and analysis

As for chest CT data, one 77-year-old severe patient underwent a chest CT scan in another hospital and died the day after admission, so we failed to obtain his CT data. All remaining patients underwent non-contrast enhanced chest CT in Jinyintan hospital. All images were analyzed independently by two chest radiologists (J.L and YK.C) with 5–7 years of experience, and final decisions were reached by consensus. The imaging analysis mainly focused on the lesion features of each patient, such as distribution pattern and important CT signs of COVID-19 pneumonia. The extent of lesion involvement was categorized as focal, multifocal, or diffuse. The location of the lesion was categorized as peripheral, central, or peripheral and central. We also quantified the CT images with a previously published method (Ooi et al., 2004). We defined the evolution of lesions as an increase in size or density, and the improvement as decrease in lesion size or resorption of the ground-glass opacities and consolidation.

This was a retrospective, single-center case series study and no patients were involved in the study design. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital. All participants remained anonymous and written informed content was waived by the ethics commission for rapid emerging infectious diseases.

Statistical analysis

We presented the continuous measurements as median (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical variables as frequency (percentage). For laboratory results, we assessed whether the measurements were within or outside the normal range. According to the history of ART before SARS-CoV-2 infection, we have divided the patients into medicine group and non-medicine group. Laboratory results and radiologic features were compared between the two groups using Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical data. Here, we need to point out that when comparing radiologic features between two groups, the non-medicine group only contained 7 patients. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS, version 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism version 7.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla).

Results

Demographics, baseline characteristics, treatment and outcomes

Demographics, baseline characteristics, treatment and outcomes of the patients are shown in Table 1 . Twenty patients were included in the study with a median age of 46.5 (IQR, 39.3-50.5) and most cases were female (15 [75%]). Twelve of 20 patients were on ART at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis. Antiretroviral regimens included nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs, n = 12), protease inhibitors (PI, n = 8) and Non-NRTIs (n = 6). NRTIs were mainly lamivudine (n = 12), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (n = 9) and zidovudine (n = 2). PI was mainly kaletra (lopinavir/ritonavir) and Non-NRTI was mainly efavirenz.

Table 1.

Demographics, baseline characteristics, treatment and outcomes of patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV.

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 20) | Characteristics | Patients (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 46.5 (39.3-50.5) | Sore throat | 1 (5%) |

| Sex | Diarrhea | 1 (5%) | |

| Male | 5 (25%) | Abdominal pain | 1 (5%) |

| Female | 15 (75%) | Dizziness | 1 (5%) |

| Exposure History | 16 (76%) | Anorexia | 1 (5%) |

| Exposure to Huanan Seafood market | 1 (5%) | Clinical classification | |

| Exposure to Infected Patients | 15 (75%) | Non-severe | 17 (85%) |

| Unknown Exposure | 4 (20%) | Severe | 3 (15%) |

| Comorbidities | 15 (75%) | ART before SARS-CoV-2 infection | 12 (60%) |

| Hepatitis C | 8 (40%) | NRTIs | 12/12 (100%) |

| Syphilis | 4 (20%) | Non-NRTIs | 6/12 (50%) |

| Other chronic liver disease | 3 (15%) | PI | 8/12 (67%) |

| Hypertension | 3 (15%) | Treatment during hospitalization | |

| CHD | 1 (5%) | Antiviral | 19 (95%) |

| Diabetes | 1 (5%) | ART | 19 (95%) |

| Hepatitis B | 1 (5%) | Corticosteroids | 1 (5%) |

| COPD | 1 (5%) | Chinese herbals | 4 (20%) |

| Psychosis | 1 (5%) | Oxygen therapy | 3 (15%) |

| Signs and symptoms | Immunoglobulin | 2 (10%) | |

| Cough | 13 (65%) | ICU admission | 0 |

| Fever | 9 (45%) | Outcome | |

| Expectoration | 5 (25%) | Discharged | 19 (95%) |

| Shortness of breath | 4 (20%) | Died | 1 (5%) |

| Fatigue | 2 (10%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; CHD, coronary heart disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NRTI, snucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; Non-NRTIs, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI, protease inhibitors; ART, antiretroviral therapy; ICU, intensive care unit.

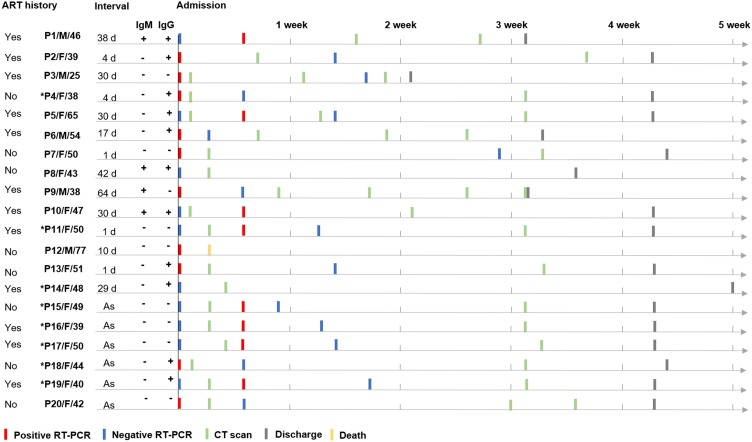

The clinical course of the patients as well as the results of IgM/IgG antibodies obtained on admission are shown in Figure 1 . On admission, the total seropositive rate for IgM and IgG was 20% (4/20) and 55% (11/20), respectively. Ten patients had initial negative RT-PCR on admission, of whom 8 patients showed positive results of RT-PCR four days later, 5 showed normal CT appearance, and 4 were asymptomatic cases. After admission, one severe patient, a 77-year-old male with several combined diseases (COPD, and alcoholic liver disease), died the day after admission due to septic shock and multiple organ failure. The rest of the patients all received antiviral treatment and ART after admission, and were discharged with a median hospital stay of 30 days (IQR, 26-30). None of the patients were admitted to intensive care units (ICU).

Figure 1.

Chart of the clinical courses in 20 patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; Interval, time interval between symptoms onset and admission; As, asymptomatic; F, female; M, male.

*Patient with normal CT appearance.

Laboratory and radiologic findings

Laboratory and radiologic findings are summarized in Table 2, Table 3 , respectively. On admission, leukocytes were below the normal range in five patients (25%). Lymphocytes were low in 9 patients (45%). Only one of the severe patients had high serum levels of myoglobin (786 ng/mL), procalcitonin (31.8 ng/mL) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP > 160.0 mg/L).

Table 2.

Laboratory results of patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV on admission.

| Variables | Normal range | Total (n = 20) |

Medicine group (n = 12) | Non-medicine group (n = 8) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Increased | Decreased | |||||

| Leukocytes (× 10⁹/L) | 3.5–9.5 | 4.4 (3.5-5.3) | 5 (25%) | 4.5 (3.9-5.3) | 3.7 (3.0-5.8) | 0.343 | |

| Neutrophils (× 10⁹/L) | 1.8–6.3 | 2.5 (2.2-3.2) | 2 (10%) | 2.5 (2.2-3.2) | 2.5 (2.0-3.9) | 0.970 | |

| Lymphocytes (× 10⁹/L) | 1.1–3.2 | 1.1 (0.9-1.9) | 9 (45%) | 1.3 (1.0-1.9) | 1.1 (0.7-1.9) | 0.545 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 110.0-150.0 (female) 120.0–160.0 (male) |

117.0 (106.0-128.0) | 6 (30%) | 120.0 (109.0-131.0) | 114.5 (98.5-121.5) | 0.238 | |

| Platelets (× 10⁹/L) | 125.0–350.0 | 168.5 (135.8-196.3) | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) | 165.0 (134.0-193.0) | 180.0 (134.0-198.0) | 0.681 |

| D-dimer (µg/L) | 0.0–1.5 | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 2 (10%) | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 0.4 (0.3-0.8) | 0.805 | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.0–55.0 | 37.7 (32.9-40.4) | 13 (65%) | 37.5 (33.0-41.3) | 37.8 (28.8-40.1) | 0.791 | |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 3.9–6.1 | 5.4 (4.6-6.4) | 7 (35%) | 5.2 (4.4-6.4) | 6.2 (4.7-7.8) | 0.417 | |

| CK (U/L) | 50.0–310.0 | 56.0 (50.0-77.0) | 1 (5%) | 4 (20%) | 56.0 (42.0-77.0) | 57.5 (53.5-76.5) | 0.657 |

| LDH (U/L) | 120.0–250.0 | 191.0 (176.0-310.0) | 5 (25%) | 191.0 (162.0-207.0) | 188.0 (177.5-313.5) | 0.717 | |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 0.0–146.9 | 25.2 (19.1-41.9) | 1 (5%) | 29.9 (12.9) | 23.5 (14.5-53.1) | 0.805 | |

| AST (U/L) | 15.0–40.0 | 33.5 (26.0-57.8) | 8 (40%) | 33.0 (26.0-56.0) | 34.0 (26.0-63.0) | 0.860 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 9.0–50.0 | 27.5 (12.5-55.0) | 4 (20%) | 17.0 (11.0-73.0) | 36.0 (26.0-49.0) | 0.328 | |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 57.0–111.0 | 56.3 (50.3-63.9) | 1 (5%) | 10 (50%) | 60.9 (50.3-65.7) | 53.6 (49.0-59.2) | 0.408 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.0–5.0 | < 0.05 (< 0.05-0.06) | 1 (5%) | ||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 0.0–7.0 | 6.7 (5.5-8.0) | 8 (40%) | 6.6 (5.6-7.9) | 6.7 (5.5-8.3) | 0.711 | |

| ESR (mm/h) | 0.0–15.0 | 34.0 (13.0-53.0) | 14 (70%) | 14.0 (10.0-34.0) | 51.0 (35.8-62.0) | 0.005* | |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL) | 21.0–274.7 | 163.5 (52.8-607.2) | 6 (30%) | 2 (10%) | 174.7 (56.5-532.6) | 78.1 (47.2-150.1) | 0.351 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.8-8 | 0.6 (0.4-2.4) | 1 (5%) | 0.5 (0.2-1.3) | 2.1 (0.4-5.9) | 0.074 | |

| CD4 cell count | 500-1500 | 237.0 (142.5-346.8) | 20 (100%) | 249.0 (117.0-424.0) | 195.0 (143.0-290.0) | 0.791 | |

| CD4/CD8 | 1.4-2.0 | 0.4 (0.2-0.6) | 20 (100%) | 0.5 (0.3-0.6) | 0.4 (0.2-0.5) | 0.536 | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; CK, creatine kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IL-6, interleukin-6; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Findings on initial chest CT scan in 19 patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV.

| CT features | Total (n = 19) | Medicine group (n = 12) | Non-medicine group (n = 7) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal/Abnormal | 8/11 (42%/58%) | 5/7 | 3/4 | 0.960 |

| Extent | ||||

| Focal | 2 (11%) | 2 | 0 | 0.253 |

| Multifocal | 8 (42%) | 3 | 4 | 0.161 |

| Diffuse | 2 (11%) | 2 | 0 | 0.253 |

| Location | ||||

| Peripheral | 8 (42%) | 4 | 4 | 0.311 |

| Central | 0 | |||

| Peripheral and central | 4 (21%) | 3 | 0 | 0.149 |

| CT features | ||||

| Ground-glass opacities | 11 (58%) | 6 | 4 | 0.764 |

| Consolidations | 6 (32%) | 3 | 2 | 0.865 |

| Mixed pattern | 1 (5%) | 1 | 0 | 0.433 |

| Fibrotic streaks | 5 (26%) | 3 | 2 | 0.865 |

| Subpleural transparent line | 1 (5%) | 1 | 0 | 0.433 |

| Air bronchogram | 3 (16%) | 2 | 0 | 0.253 |

| Bronchial distortion | 2 (11%) | 2 | 0 | 0.253 |

| Pleural retraction | 3 (16%) | 1 | 0 | 0.433 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | - | - | - |

| Enlarged lymph nodes | 0 | - | - | - |

| CT score | Mean, 4.7 (Min-Max, 0-20) | Mean, 5.2(Min-Max, 0-20) | Mean, 2.2 (Min-Max, 0-5) | 0.892 |

Abbreviations: Min-Max, Minimum value - Maximum value.

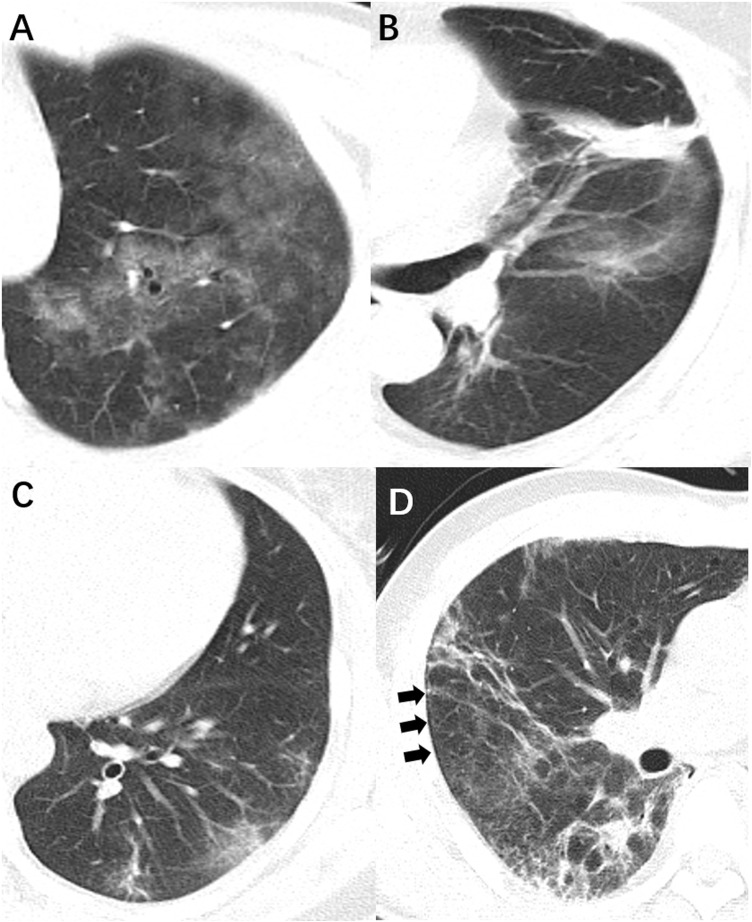

The mean interval from symptom onset to the first CT scan was 25.8 days (SD, 21.8). Of 19 patients with chest CT scans, 8 non-severe patients showed normal chest CT appearance of both lungs. As shown in Figure 2 , the predominant CT features were multiple [8 (42%)] ground-glass opacities [11 (58%)] and consolidations [6 (32%)]. Fibrotic streaks were seen in 5 patients (26%). Pleural effusion and enlarged lymph nodes were not present.

Figure 2.

CT features in patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. (A) Diffuse ground-glass opacities; (B) patchy consolidation; (C) fibrotic streak; (D) subpleural transparent line (arrows).

ESR in the medicine group was significantly lower than that in the non-medicine group (P = 0.005). hsCRP was also lower in the medicine group compared with that in the mon-medicine group [Median (IQR): 0.5 (0.2-1.3) vs. 2.1 (0.4-5.9)], but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.074). Other laboratory parameters and all CT features showed no statistical difference (P > 0.05) between the two groups.

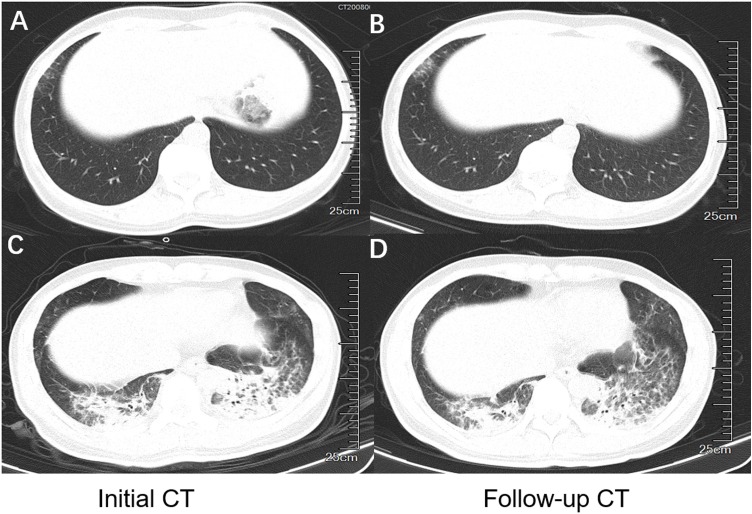

The dynamic profile of chest CT images

Seventeen patients underwent several follow-up CT scans with a median of 2 times. The median interval between the initial and second CT scans was 20 days (IQR, 8-21). Five patients (26%) showed improvement on the second CT scan, while 2 patients (11%) showed worsening (Figure 3 ). Eight patients with initial normal CT scan remained normal on the follow-up chest CT scans.

Figure 3.

Dynamic changes of CT images in patients with co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. (A and B) 50-year-old female, non-severe type. Follow-up CT scan showed increased density of the ground-glass opacity in the right lower lobe 21 days after initial scan. (C and D) 38-year-old male, severe type. Follow-up CT scan showed partial resorption of consolidation in the left lower lobe 8 days after initial scan.

Discussion

COVID-19 is a severe infectious disease with a capability of human-to-human transmission (Li et al., 2020, Lu et al., 2020), which caused a large number of deaths around the world. Patients included in our study were diagnosed using a combination of viral RNA RT-PCR and IgM/IgG antibody test according to the seventh edition of China National Health Commission guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia (General Office of the National Health Committee of China, 2020a). As previously reported, the test of IgM/IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 provides important immunological evidence and can be an effective supplementary indicator in diagnosing the suspected cases with no detectable viral RNA (Gao et al., 2020).

In our study, some patients were tested negative for RT-PCR nucleic acid and IgM/IgG antibodies on admission, while the results of viral RNA test turned positive a few days later. Several reasons may contribute to this phenomenon. Firstly, some of the patients were initially isolated in the compartment hospital, and when admitted to Jinyintan hospital, they were at a stage with a low RNA positive rate, and a high IgM negative and IgG positive rate indicating a late stage of the infection. Secondly, some asymptomatic cases sought medical treatment in the early stage due to a history of close contact with infected patients, in whom temporal negative results may present because of a low viral load.

Our study showed that the predominant gender was female (75%), contradicting with the findings in previous studies (Gervasoni et al., 2020, Harter et al., 2020, Vizcarra et al., 2020). Such a discrepancy may be due to the different risk behavior between study populations. As the priority was to initiate a timely treatment for COVID-19 patients, clinicians were not aware of the risk behavior concerning HIV infection. Most patients (75%) were infected by close contact with confirmed patients, which is reported to be the current main source of infection (Chen et al., 2020a, Chen et al., 2020b). The clinical characteristics in patients co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and HIV are similar to those in the general population. Except for three severe cases, the rest of the patients (17/20) exhibited mild or moderate symptoms, with predominant presentation of cough and fever. Laboratory tests revealed low peripheral blood leukocytes (25%) and lymphocytes (45%) counts. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Chen et al., 2020a, Chen et al., 2020b, Guan et al., 2020), which suggests that COVID-19 mainly acts on lymphocytes, especially T lymphocytes. But the extent of lymphocytes decrease in our study (Mean, 1.3; SD, 0.6) was relatively small compared with a previous study published by China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19 (Median, 1.0; IQR, 0.7-1.3) (Guan et al., 2020).

In terms of radiologic findings, we summarized the features of 19 patients who underwent chest CT scans after admission. The predominant CT findings on the first scan were multifocal ground-glass opacities, which were linked to variable histopathologic changes, such as diffuse alveolar damage or interstitial inflammatory cell infiltration (Kanne et al., 2007). Consolidation was also a typical finding in our case series, occasionally combined with air bronchogram. Fibrotic changes were shown in 5 patients, which is often seen as a form of chronic change during the remission stage. Ying Xiong et al reported that most patients (83%) exhibited a progressive process on the follow-up CT scans (Xiong et al., 2020). In our study, abnormal CT appearance in most of the patients remained unchanged or improved on the second scan. Normal CT appearance was seen in 8 patients, which accounted for nearly half of the patients. Previous studies also reported cases with normal CT scans (Chung et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020), which may be related to the relatively weak immune response in HIV patients. Besides, it suggests that we cannot reliably fully exclude cases by normal imaging studies. Patients showing initially negative for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test can also have abnormal CT findings (Ai et al., 2020). Given the sensitivity of chest CT, a clinical diagnostic standard based on typical CT characteristics was adopted in the revised 5th edition of the Guideline of Diagnosis and Treatment, which was only applicable in Hubei Province, China (General office of the National Health Committee of China, 2020b). Therefore, chest imaging still plays an important role in the diagnosis and assessment of the patient’s condition.

In our study, ESR of patients who have received ART before SARS-CoV-2 infection was significantly lower than that of patients without ART (P = 0.005). Besides, hsCRP was also lower in patients with a previous history of ART than that in patients without ART history [Median (IQR): 0.5 (0.2-1.3) vs. 2.1 (0.4-5.9)], but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.074). Another important inflammatory marker; Interleukin-6 (IL-6); showed no difference between the two groups. A previous study revealed that ART can reduce the systemic inflammation and immune activation in HIV patients (Hileman and Funderburg, 2017). We propose that the inflammatory response last longer in patients without a treatment history of antiretroviral, so an elevated ESR level (which can help monitor chronic inflammation) may be observed in the chronic/recovery stage of the infection. The extent of inflammatory response may be minimized by a previous history of ART in HIV-infected patients. Further large-scale studies are warranted to clarify and explain the effect of ART use on the inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The laboratory test results and radiologic findings both showed that most patients experienced mild illness. As reported, in immunocompromised population, the host response to the virus may be an important contributor to the disease process (D’Antiga, 2020). When infection occurrs in immunocompromised population who have some persistent immune activity, they may be protected by a weaker immune response against the pathogen. As a result, the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 infection may not progress to a severe cytokine storm in this population (Hileman and Funderburg, 2017). In the last two outbreaks of coronavirus (SARS and MERS), patients with immunocompromised status were not found to have an increased risk of severe pulmonary involvement, complications, or a poorer prognosis (Hui et al., 2018, D’Antiga, 2020). Another possibility of mild manifestation of symptoms, laboratory results and chest CT scans in our study could be related to the early admission and early intervention. Some asymptomatic patients sought medical advice once they were aware of a suspicious contact history. HIV patients might have a higher opportunity for being tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection even in mild or moderate cases, given that they are usually considered at high risk of infection, especially in an epidemic outbreak.

In our study, one severe patient (a 77-year-old male with several comorbidities) died the day after admission due to septic shock and multiple organ failure. Other 19 patients were discharged after corresponding treatment. Up to now, no specific drug has been confirmed effective for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Due to the unique sample, except for one severe case which deceased after admission, all of the patients received ART during the hospitalization (they had their usual ART, and some of them modified the regimen to include lopinavir/ritonavir), therefore expecting both antiretroviral and anti-SARS-CoV-2 effects (Choy et al., 2020). Our study showed low proportion of individuals with severe diseases (n = 3) and ICU admission (n = 0), which were lower than previous studies (Harter et al., 2020, Vizcarra et al., 2020). Vizcarra and colleagues pointed out that in HIV population, severe COVID-19 disease, ICU admission, low nadir CD4 cell counts, and comorbidities could help identify individuals with delayed viral clearance even after clinical improvement (Vizcarra et al., 2020). Current data suggest that the main mortality risk factors are still linked to older age and multimorbidity, not particularly to HIV (Mirzaei et al., 2020, World Health Organization, 2020b).

Our study had some limitations. This single-center study was limited by its retrospective nature and small sample size. HIV viral load was not measured because of the great pressure on the medical supplies and staff regarding COVID-19 treatment at that time, and the dynamic changes of IgM/IgG antibodies during hospitalization was not evaluated due to the limited number of patients with multiple tests of antibodies.

In conclusion, compared with SARS-CoV-2 infected general population, patients with HIV co-infection mostly have milder clinical presentation. A single test of viral RNA test and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 might be insufficient to exclude COVID-19 infection in patients with HIV. The lesser extent of inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 infection might be associated with a previous history of ART in HIV-infected patients. The association between inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 and history of ART use requires further assessment on large-scale studies.

Authors’ contributions

Heshui Shi, Yanqing Fan, and Fan Yang conceived the study. Jia Liu, Wenjuan Zeng and Yukun Cao participated in the study design. Yue Cui and Yumin Li collected the data. Osamah Alwalid and Sheng Yao performed the statistical analysis. Jia Liu and Wenjuan Zeng drafted of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by Zhejiang University special scientific research fund for COVID-19 prevention and control, the HUST COVID-19 Rapid Response Call (grant number 2020kfyXGYJ019). The funders only provided funding and had no influence on the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital. All participants remained anonymous and written informed content was waived by the ethics commission for rapid emerging infectious diseases.

Potential conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there were no competing interests.

References

- Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/. [Accessed 31th July 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Fan Y., Lai Y., Han T., Li Z., Zhou P. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020;92(4):424–432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Du RH Li B, Zheng X., Yang X.S., Hu B. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):386–389. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito N., Moreno A., Miro J.M., Torres A. Pulmonary infections in HIV-infected patients: an update in the 21st century. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(3):730–745. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco J.L., Ambrosioni J., Garcia F., Martínez E., Soriano A., Mallolas J. COVID-19 in patients with HIV: clinical case series. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(5) doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30111-9. e314-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervasoni C., Meraviglia P., Riva A., Giacomelli A., Oreni L., Minisci D. Clinical features and outcomes of HIV patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa579. ciaa579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter G., Spinner C.D., Roider J., Bickel M., Krznaric I., Grunwald S. COVID-19 in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a case series of 33 patients. Infection. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiolo F., Zoboli F., Arosio M., Valenti D., Guarneri D., Sangiorgio L. SARS-CoV-2 infection in persons living with HIV: a single center prospective cohort. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26352. (accepted article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcarra P., Perez-Elias M.J., Quereda C., Moreno A., Vivancos M.J., Dronda F. Description of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a single-centre, prospective cohort. Lancet HIV. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30164-8. (accepted article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F, Cao Y, Xu Sy, Zhou M. Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV in a patient in Wuhan city, China. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25732. (accepted article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the National Health Committee of China . 2020. China Traditional Chinese Medicine Administration Office. Diagnosis and treatment plan of novel coronavirus pneumonia (seventh trial edition) Available from: http://www.satcm.gov.cn/d/file/p/2020/03-04/ddfd72721be1d510657c1cb0a42cb045.pdf##ce3e6945832a438eaae415350a8ce964.pdf##4.37%20MB. [Accessed 3rd March 2020] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when Novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. [Accessed 27th May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi G.C., Khong P.L., Müller N.L., Yiu W.C., Zhou L.J., Ho J.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004;230(3):836–844. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Guan X.H., Wu P., Wang X.Y., Zhou L., Tong Y.Q. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R.J., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P.H., Yang B., Wu H.L. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Yuan Y., Li T.T., Wang X.W., Li X.Y., Li A. Evaluation of the auxiliary diagnostic value of antibody assays for the detection of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25919. (accepted article) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.M., Fu J.F., Shu Q., Chen Y.H., Hua C.Z., Li F.B. Diagnosis and treatment recommendations for pediatric respiratory infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus. World J Pediatr. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N.S., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J.M., Gong F.Y., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanne J.P., Godwin J.D., Franquet T., Escuissato D.L., Müller N.L. Viral pneumonia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: high resolution CT findings. J Thorac Imaging. 2007;22(3):292–299. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e31805467f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Sun D., Liu Y., Fan Y.Q., Zhao L.Y., Li X.M. Clinical and High-Resolution CT Features of the COVID-19 Infection: Comparison of the Initial and Follow-up Changes. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(6):332–339. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Huang M., Zeng X. CT Imaging Features of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295(1):202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Liu J., Zhao X., Liu C., Wang W., Wang D. Clinical Characteristics of Imported Cases of COVID-19 in Jiangsu Province: A Multicenter Descriptive Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa199. ciaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai T., Yang Z.L., Hou H.Y., Zhan C.N., Chen C., Lv W.Z. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020:200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General office of the National Health Committee of China . 2020. Notice on the issuance of a program for the diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (trial revised fifth edition) Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/3b09b894ac9b4204a79db5b8912d4440.shtml [Accessed 4th February 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Hileman C.O., Funderburg N.T. Inflammation, Immune Activation, and Antiretroviral Therapy in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2017;14(3):93–100. doi: 10.1007/s11904-017-0356-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D.S., Azhar E.I., Kim Y.J., Memish Z.A., Oh M.D., Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: risk factors and determinants of primary, household, and nosocomial transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(8) doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30127-0. e217-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Antiga L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: The facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transpl. 2020;26(6):832–834. doi: 10.1002/lt.25756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy K.T., Wong A.Y.L., Kaewpreedee P., Sia S.F., Chen D., Hui K.P.Y. Remdesivir, lopinavir, emetine, and homoharringtonine inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2020;178 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei H., McFarland W., Karamouzian M., Sharifi H. COVID-19 Among People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2020;30:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02983-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]