Abstract

The role of mitochondria in cardiac tissue is of utmost importance due to the dynamic nature of the heart and its energetic demands, necessary to assure its proper beating function. Recently, other important mitochondrial roles have been discovered, namely its contribution to intracellular calcium handling in normal and pathological myocardium. Novel investigations support the fact that during the progression toward heart failure, mitochondrial calcium machinery is compromised due to its morphological, structural and biochemical modifications resulting in facilitated arrhythmogenesis and heart failure development. The interaction between mitochondria and sarcomere directly affect cardiomyocyte excitation-contraction and is also involved in mechano-transduction through the cytoskeletal proteins that tether together the mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The focus of this review is to briefly elucidate the role of mitochondria as (mechano) sensors in the heart.

Keywords: mechanoelectric feedback, calcium handling, arrhythmias, microtubules, oxidative stress

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), with almost 18 million deaths per year, are the first cause of death globally (World Health Organization). The heart is one of the most energy-demanding organs in the body, due to its intrinsic nature to continuously pump blood into the systemic and pulmonary circulation. The heart modulates its function via a plethora of physiological and metabolic processes, necessary to supply oxygen, biochemical and biomolecular signals, and metabolites to the entire body (1). One of those physiological processes is the mechano-transduction that, via several actors like stretch-activated channels (SACS (2)), the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (3), ryanodine receptor (RyR (4)), structural proteins (5) oxidative species (6), hormones (7, 8), and ion channels (9), modulate calcium signaling in the myocytes and the pumping function of the heart.

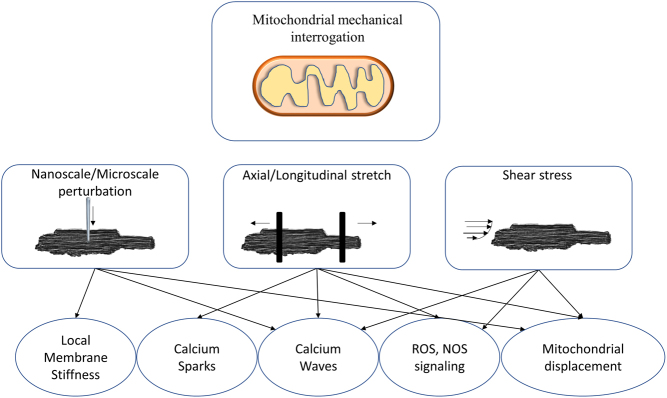

The cardiomyocytes, along with fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and other cells that form the heart, host the majority of most mitochondrial when compared to all the other cells in the entire body (10). The role of mitochondria in cardiac diseases has been extensively studied both in vitro and in vivo, by mainly focusing on mitochondrial structural, functional, and metabolic remodeling (11). However, with respect to calcium-based contraction machinery, clear evidence showed that mitochondria ‘sense’ the mechanics of the heart and, by a complex mechanoelectric and mechanochemical feedback process, adjust their modulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis (12). Deciphering the mechanosensing features of mitochondria is challenging, as only a few instruments and approaches can localize or stimulate mitochondria in live cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the discussed technologies and approaches for mitochondrial interrogation in live cardiomyocytes. Left: Nanoscale perturbation, achieved by scanning probe microscopy. Middle: Axial stretch, achieved by piezoelectric translator of carbon fibers. Right: Shear stress, achieved by pressurized flow solution trough microbarrels.

Mitochondria calcium handling regulation: mechanical-induced calcium propagation

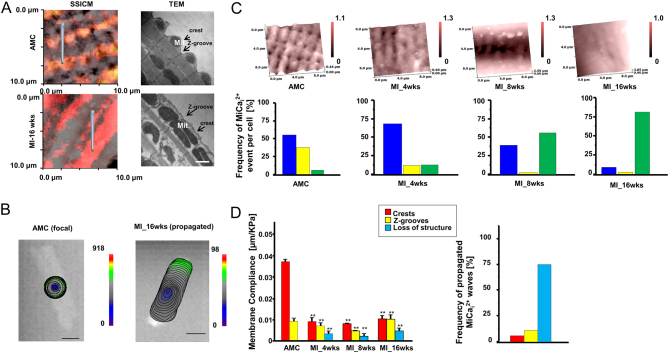

Scanning ion conductance microscopy (SICM) is one of the few techniques capable of providing (13, 14) a detailed investigation into subsarcolemmal mitochondria which are located underneath the membrane crest (Fig. 1). SICM delivers a dedicated hydrojet of solution (normally Phosphate Buffered Saline, PBS, or Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution, HBSS) via a borosilicate pipette probe after having acquired a contactless high-resolution topographical scan with the same high-resistance nanopipette (100 MΩ). SICM can be combined with surface confocal microscopy (SSICM) (15) to increase scan details by showing fluorescent mitochondrial position within the conductance topographical images (10 × 10 µm, 512 × 512 pixels) (Fig. 2A). In our recent research (16), rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (either from healthy or failing heart) were first loaded with a calcium indicator. In particular, failing heart cardiomyocytes were isolated from ventricular zones remote from the scar, and failing heart was generated through myocardial infarction by coronary artery occlusion. In the present model, rats develop heart failure at 16 weeks with clear evidence of hypertrophy and left ventricular failure. After topography acquisition, 20 kPa of hydrojet for two seconds was delivered either on the crest (i.e. on top of the mitochondria) or in the unstriated part of the failing cardiomyocytes to perturb mitochondrial mechanical state. It was observed that, while in healthy adult cardiomyocytes the mechanical hydrojet activates a local mechanical-induced intracellular Ca2+ release (MiCai) (Fig. 2B and C), in failing cardiomyocytes the MiCai propagates throughout the cells, suggesting a possible mechano-sensing role of mitochondria in arrhythmogenesis. The hydrojet released via SICM can also provide the membrane compliance on the perturbed area; it was also observed that the stiffer is the membrane the higher the probability of generating MiCai (Fig. 2D) (16). Mitochondria calcium serves as a trigger for activating calcium waves in failing cardiomyocytes, possibly involving the cytoskeleton or reactive species. Such remodeling, together with the ‘loading’ role of SR (17), has been recently suggested to play an active role in calcium propagation in failing cardiomyocytes. However, further investigations are needed.

Figure 2.

Mechanically-induced Ca2+ release in failing rat ventricular myocytes. (A) Surface topographical and confocal images (left) and transmission electronic microscopy images (right) of normal (top) and failing (bottom) portion of cardiomyocytes. In particular, as adult male Sprague–Dawley rats underwent proximal left anterior descending coronary ligation to induce chronic MI (heart failure was developed at 16 weeks), only cardiomyocytes from ventricular zones remote from the scar were utilized. (B) Representative optical images (color-coded isochrones) for AMC cell (local propagation) and infarcted-16-week-old cells (total-propagation). (C) Frequency of propagated mechanical induced Ca2+ transient (MiCai) in aged match control (AMC) cells and in infarcted cells after 4, 8, and 16 weeks following anterior coronary legation, respectively. Blue: not propagated; yellow: local propagation; green: total-cell propagation. (D) Membrane compliance obtained on crests, Z-grooves and unstriated parts of the cells in the aforementioned conditions (left) and frequency of propagated MiCai. Modified from (14) and (16) with permission.

Mitochondria calcium handling mechanisms: sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS)

The sarcoplasmic reticulum is the main source of calcium-induced-calcium release (CICR), and it is in intimate contact with mitochondria forming within the dyad a functional unit. Calcium sparks are the first elementary event of CICR, which are locally confined around the RyR cluster (mainly the same mechanism that we described previously in healthy nanomechanical stimulated cells). In CIRC L-type, Ca channels that open RyR trigger a rise of intracellular Ca2+ moving from the SR, but such opening may occur spontaneously when RyR is sensitized to Ca2+ by phosphorylation, oxidation or nitrosylation. Of interest, shear stress and axial stretch applied to a cardiomyocyte immediately cause a release of bursts of Ca2+ sparks that terminate within a second with a time course that depends on the increment in ROS (6, 18, 19).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in cardiomyocytes are normally generated by mitochondria, NADPH oxidase (NOX), xanthine oxidase (OX), and nitric oxide synthase (NOS). In fact, mitochondria are the main source of ROS in cardiomyocytes, and superoxide generation is the result of oxygen leaking from the electron transport chain that, together with other enzymes, can participate in ROS generation, in particular, due to complexes I and III (20). ROS and RNS accumulation in the cell is finely controlled by several antioxidant components, including glutathione, catalase, superoxide dismutase, and others. While high concentrations of ROS and RNS are toxic to cells, by altering the activity of several antioxidant enzymes (21), low concentration can play an important role as signaling molecules. In particular, nitric oxide can regulate endothelium-dependent epicardial and microvascular vasodilatation, ROS provide cardiac protection during ischemic preconditioning, and RNS can modulate sympathetic cardiac activity (22, 23).

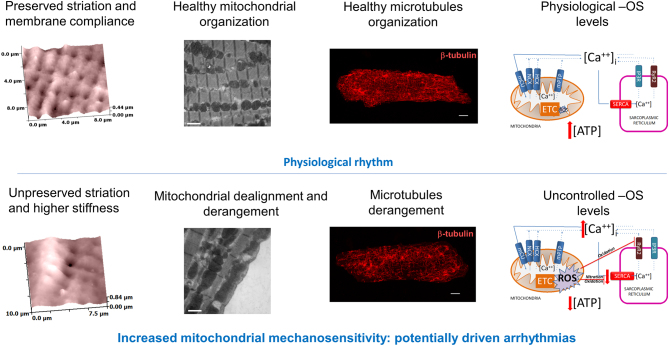

Furthermore, ROS and RNS are both protagonists in orchestrating calcium homeostasis within the cardiomyocytes (24); ROS are imperative in modulating the amplitude of calcium signals, while RNS have a role in modulating the calcium uptake in the SR via the SERCA2a protein (25). Much evidence has shown the relationship between Ca2+ and ROS generation in mitochondria under physiological and pathological conditions (26). The combination of mitochondrial dealignment, microtubule disorganization, and uncontrolled level of oxidative stress, as happens in failing cardiomyocytes, may drive spontaneous calcium waves and arrhythmias (Fig. 3). Mitochondrial calcium concentration plays a critical role in maintaining the normal functionality of these organelles (27). Under physiological conditions, mitochondrial calcium uptake by calcium uniporter (MCU) complex is required to sustain energy demand and to keep the antioxidative capacity in a reduced state (28). In heart failure, the increment of diastolic calcium (29, 30) prevents mitochondrial calcium uptake when cytosolic Ca2+ > 400 nM (31), hampering regeneration of reduced forms of NAD and NADPH and leading to a status of energetic stress and ROS generation (32). In heart failure, Ca2+/Calmodulin 2 is upregulated and evidently increases the amount of cytosolic Na+ concentration and late inward INa (33). This increment can also lead spontaneous release of Ca2+ from SR, triggering arrhythmias.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation underpinning the known mechanism for potentially driven mitochondrial related mechanically induced arrhythmias. Top: healthy condition; Bottom: failing condition. Modified from (16) and (25) with permission.

Mitochondrial ROS generation induces more mitochondrial ROS production in a phenomenon called ROS-induced ROS release (34). Under physiological conditions, the proper handling of mitochondrial calcium concentrations is fundamental for efficient oxidative phosphorylation activation and maintenance of reduced NADPH, both contributing to cardiomyocyte pump function and energy. High NADPH generation is essential for ROS mitochondrial enzymes scavenging activities (35). A reduced ability to scavenge mitochondrial ROS generation occurs in experimental models of heart failure (36). In heart failure, the altered mitochondrial calcium uptake leads to higher concentration of ROS and to a reduced conversion of NADH to NADPH by the mitochondrial enzyme nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase, lowering ROS enzymes scavenging activities, thereby weakening the cellular antioxidant defense (37). High ROS levels interfere with excitation–contraction coupling and induce cell death through mitochondrial permeability transition (6, 26). In a rat heart failure model, the reduction of mitochondrial ROS generation (in particular, hydrogen peroxide) and of calcium-induced mitochondrial permeability transition contributes to the beneficial effect of aerobic exercise on mitochondria efficiency by reestablishing their number and size in cardiomyocytes (38). Prosser et al. (39) demonstrated that, under physiological conditions, stretching of heart cells activates NOX2 and leads to the generation of ROS in a process that depends on microtubules, called ‘X-ROS signaling’. Briefly, a mechano-chemical increase in ROS activates ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) inducing a calcium burst, which leads to muscle contraction (4). After the contraction, calcium concentrations return to basal levels inducing muscle relaxation. On the contrary, in diseased cardiomyocytes the ‘X-ROS signaling’ generates arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves, contributing to cardiomyopathy in a model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (40). SERCA2a is an integral endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) membrane protein that mediates active transport of calcium, helping to maintain normal calcium concentrations in the ER/SR lumen. In particular, in the heart the subtype SERCA2a is present and contribute to myocyte contraction and calcium reuptake in the SR. SERCA2a is located closely to mitochondria, exposing it to ROS and RNS species generated by oxidative phosphorylation. Pathological conditions implying high concentrations of peroxynitrite bring irreversible inactivation of SERCA2a through nitration. Lokuta et al. showed that, in human heart failure, the inactivation of SERCA2a by nitration might contribute to calcium pump failure (41).

Mitochondrial calcium handling mechanisms: microtubules-dependent mitochondrial trafficking, deformation and organization implicated in mechano-electrical transduction

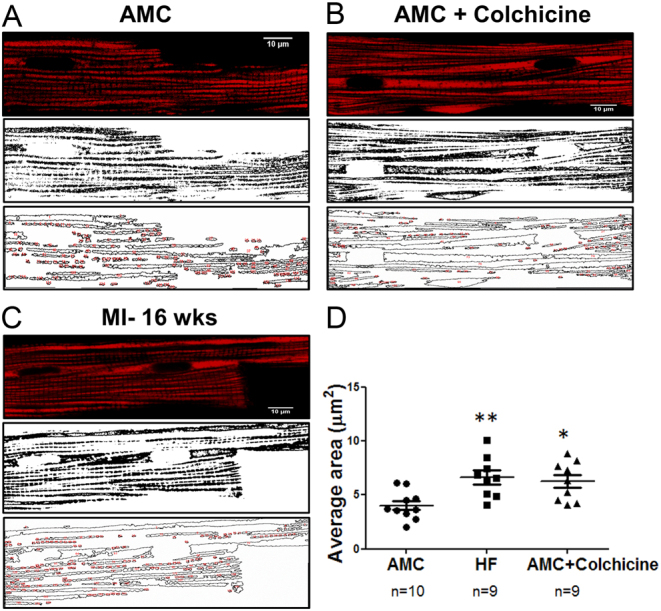

The integrity of microtubules, as part of the cytoskeleton, is tightly controlled in the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes. It has been demonstrated that, during the stretch-induced mitochondrial membrane (ΔΨm) potential hyperpolarization (42), microtubules integrity is necessary for the regulation of the respiratory function (16, 43, 44, 45). Tubulin is directly associated with mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs), which are located in the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) (46). There is evidence that free tubulin dimers, in isolated cardiac mitochondria (in vitro), increase appKm for ADP, thus, decreasing ADP availability to ATP-ADP translocase (ANT). Moreover, VDAC and ANT are linked to mitochondrial creatine kinase (MitCK), and all three together have an important role in the control of metabolic energy and metabolic fluxes (43, 45, 47, 48). Recently, a link has been demonstrated between mitochondrial activity, cardiac preload modulation via Frank–Starling mechanisms, microtubules, and mitochondria X-ROS production (39, 42); however, further investigation is necessary to characterize the underlying mechanism. Subsarcolemmal mitochondria (and possibly interfibrillar mitochondria) deform during sarcomere contraction, and it is possible to appreciate a diastolic and a ‘systolic dimension’ of the organelles (49, 50). Importantly, mitochondria can move within the cytoplasm, trafficking among cells in neurons (51) and also fuse with adjacent mitochondria or split in two parts by fission mechanisms (Fig. 4A and B) (16, 49). In the failing heart, cells and microtubules encounter an upregulation of the constituent proteins, resulting in profound depolymerisation as well as derangement. This is one of the possible underlying mechanisms of MiCai, as induced by pharmacological depolymerisation of healthy cardiac cells with colchicine, followed by nano-perturbation via hydrojet (16) (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Effect of microtubules derangement and inhibited-polymerisation on the total mitochondrial area. (A) Aged-match control cells, whereby mitochondria were loaded with TMRM (top) and the same binarized image (middle) for mitochondrial area calculation (bottom). (B) Same as (A) for AMC-cells treated with 10 µmol/L of colchicine. (C) Same as (A) for MI-16 weeks cardiomyocyte. (D) Total mitochondrial area calculation in the three conditions. Data represented as Mean ± s.e.m. Modified from (16) with permission.

Considerations about mitochondrial pro-arrhythmogencity via mechanosensing transduction

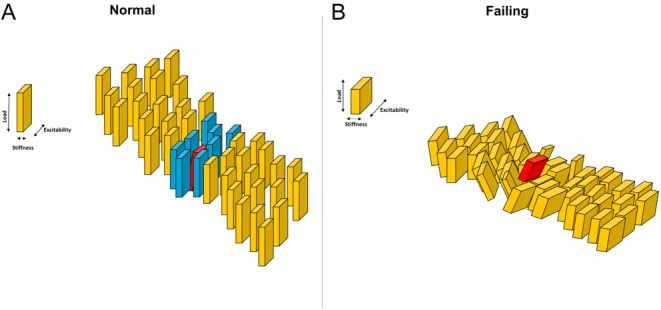

It is well known that single or minimal groups of cells are capable of evoking an abnormal bioelectrical impulse initiation and propagation. However, in vivo, the mechanism has yet to be explored. At a single failing cell level, we observed that MiCai driven from mitochondria is able to trigger a secondary distant source of calcium waves, probably from stretch-activated channels (SACs) following the nanoindentation applied at the center of the failing cardiomyocyte (14). The local sarcomere contraction underneath the mechanical interrogation relaxes, while the more distant sarcomere contracts. This secondary phenomenon is abolished when SACs are blocked either with 30 μmol/L gadolinium or 100 μmol/L streptomycin. It has been speculated that the aforementioned conditions are able to mechanically perturb the neighboring cardiomyocytes, especially in the context of sarcomere desynchronization (52). Several mathematical and experimental models have shown that for triggering an impulse initiation, it is necessary to perturb a ‘liminal area’ in the cardiac tissue (53, 54, 55), as a single failing cardiomyocyte cannot jeopardize the entire electrical activity of the heart. All multicellular models consider cardiomyocytes to be almost identical among each other in terms of electrical, mechanical, and structural functions. However, in real, cardiomyocytes are not identical, thus with the intent to explain what is happening in vivo, it represents a notable limitation. The ‘domino’ effect can represent this concept (Fig. 5). When all bricks (i.e. cardiomyocytes prone to be activated) have identical size and dimension, one has to ‘activate’ the first brick from the periphery of the failing row to cause the domino effect. Moreover, if the ‘first brick’ is in the center of the row or at other sites the domino effect does not happen or, if it does, it is limited only to the surrounding bricks (liminal area) (Fig. 5A). Considering a cell as a ‘domino brick’, if the bricks have different size, thickness, and ‘propensity to fall’ (i.e. different stiffness, energy, force, mitochondrial MiCai release, oxidative level or others unexplored trigger mechanisms), theoretically, they will be capable to partially activate a row, thus initiate an uncontrolled cumulative effect, such as re-entrant arrhythmias or propagated extrasystole (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Domino-model cartoon showing liminal area concept revisited concerning the generation of abnormal impulse propagation. Left: not generated impulse propagation; Yellow bricks: remote resting cardiomyocytes; red brick: activated ‘source’ cardiomyocyte; blue bricks: surrounded ‘sink’ cardiomyocytes sensing the activated one. Right: generated abnormal impulse propagation. Yellow bricks: surrounding and remote ‘sink’ cardiomyocytes with different size; red brick: activated ‘source’ cardiomyocyte.

Considerations about mitochondrial implication in heart failure via mechanosensing transduction

Failing myocardium is characterized by a severe impairment of energy metabolism and energy substrate utilization, resulting in an increment of glucose utilization that affects the metabolic state of the heart (12). Such remodeling is associated with a structural modification or loss of mitochondrial integrity, as observed by us and other colleagues (16, 52). Defective mitochondria, during heart failure, lack their morphology as well as cytoskeletal proteins (56) and mitofusines (57), and this alteration invariably affects mitochondrial biogenesis. Impairment of the structural interaction between mitochondria and the surrounding domain leads to cardiomyopathies. The sarcomere structure accommodates the subsarcolemmal mitochondrion underneath the crest (25) that directly interacts with the calcium-induced calcium release machinery, SERCA2 pump (58), and myofilaments of the Z-disc (59). Therefore, in failing cardiomyocytes, the sarcolemma integrity is lost (Fig. 3) along with the intimate interaction between the sarcomere and the mitochondrion. As a consequence, the mitochondrial-sarcomere intermingle is a possible candidate for delaying the progression to heart failure, aimed to push, paradoxically, the metabolic demand toward ‘controlled’ glucose utilization together with a decrease in fatty acid oxidation (60) for reducing the oxidative stress-induced microdomain remodeling.

Conclusions

The mitochondrion is an ancient eukaryotic organelle that specialized its activity during the evolution, especially in the heart, where the energy demand is higher and consistent. Similar to prokaryotic bacteria (where mitochondrion originate from), it adapts its structure and activity by sensing the mechanical force in the environment and, within a dynamic organ such as the heart, it contributes to calcium homeostasis. This review suggests a possible pro-arrhythmic involvement of mitochondria in the heart mainly due to modification in its mechanosensation, thanks to a combination of pathophysiological structural and functional remodeling occurring during heart failure. Surely, a lot of basic research needs to be spent in the field of mitochondrial mechanobiology, as the background mechanisms are still largely unexplored.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fil ‘Quota prodotti per la ricerca in ateneo’ (FIL-2018-Miragoli) to M M and by the University of Parma strategic fellowship (AR-2018-Miragoli) to C C M.

Author contribution statement

M M performed the experiments and the cartoon in Figs 1 and 5, while A C drew the cartoon in Fig. 3. C C M designed the review and wrote the manuscript with the supervision of M M and A C.

References

- 1.Bock FJ, Tait SWG. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 2020. 21 85–100. ( 10.1038/s41580-019-0173-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguettaz E, Lopez JJ, Krzesiak A, Lipskaia L, Adnot S, Hajjar RJ, Cognard C, Constantin B, Sebille S. Axial stretch-dependent cation entry in dystrophic cardiomyopathy: involvement of several TRPs channels. Cell Calcium 2016. 59 145–155. ( 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.01.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ter Keurs HE. The interaction of Ca2+ with sarcomeric proteins: role in function and dysfunction of the heart. American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2012. 302 H38–H50. ( 10.1152/ajpheart.00219.2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santulli G, Lewis D, des Georges A, Marks AR, Frank J. Ryanodine receptor structure and function in health and disease. Sub-Cellular Biochemistry 2018. 87 329–352. ( 10.1007/978-981-10-7757-9_11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyon RC, Zanella F, Omens JH, Sheikh F. Mechanotransduction in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circulation Research 2015. 116 1462–1476. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304937) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limbu S, Hoang-Trong TM, Prosser BL, Lederer WJ, Jafri MS. Modeling local X-ROS and calcium signaling in the heart. Biophysical Journal 2015. 109 2037–2050. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.09.031) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gesmundo I, Miragoli M, Carullo P, Trovato L, Larcher V, Di Pasquale E, Brancaccio M, Mazzola M, Villanova T, Sorge M, et al Growth hormone-releasing hormone attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and improves heart function in pressure overload-induced heart failure. PNAS 2017. 114 12033–12038. ( 10.1073/pnas.1712612114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo Muzio FP, Rozzi G, Rossi S, Gerboles AG, Fassina L, Pela G, Luciani GB, Miragoli M. In-situ optical assessment of rat epicardial kinematic parameters reveals frequency-dependent mechanic heterogeneity related to gender. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2020. 154 94–101. ( 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2019.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyronnet R, Nerbonne JM, Kohl P. Cardiac mechano-gated ion channels and arrhythmias. Circulation Research 2016. 118 311–329. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.305043) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piquereau J, Caffin F, Novotova M, Lemaire C, Veksler V, Garnier A, Ventura-Clapier R, Joubert F. Mitochondrial dynamics in the adult cardiomyocytes: which roles for a highly specialized cell? Frontiers in Physiology 2013. 4 102 ( 10.3389/fphys.2013.00102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beraud N, Pelloux S, Usson Y, Kuznetsov AV, Ronot X, Tourneur Y, Saks V. Mitochondrial dynamics in heart cells: very low amplitude high frequency fluctuations in adult cardiomyocytes and flow motion in non beating Hl-1 cells. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes 2009. 41 195–214. ( 10.1007/s10863-009-9214-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasqualini FS, Nesmith AP, Horton RE, Sheehy SP, Parker KK. Mechanotransduction and metabolism in cardiomyocyte microdomains. BioMed Research International 2016. 2016 4081638 ( 10.1155/2016/4081638) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shevchuk AI, Novak P, Takahashi Y, Clarke R, Miragoli M, Babakinejad B, Gorelik J, Korchev YE, Klenerman D. Realizing the biological and biomedical potential of nanoscale imaging using a pipette probe. Nanomedicine 2011. 6 565–575. ( 10.2217/nnm.10.154) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miragoli M, Cabassi A. Mitochondrial mechanosensor microdomains in cardiovascular disorders. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 2017. 982 247–264. ( 10.1007/978-3-319-55330-6_13) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz F, Swiatlowska P, Alvarez-Laviada A, Sanchez-Alonso JL, Song Q, de Vries AAF, Pijnappels DA, Ongstad E, Braga VMM, Entcheva E, et al Cardiomyocyte-myofibroblast contact dynamism is modulated by connexin-43. FASEB Journal 2019. 33 10453–10468. ( 10.1096/fj.201802740RR) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miragoli M, Sanchez-Alonso JL, Bhargava A, Wright PT, Sikkel M, Schobesberger S, Diakonov I, Novak P, Castaldi A, Cattaneo P, et al Microtubule-dependent mitochondria alignment regulates calcium release in response to nanomechanical stimulus in heart myocytes. Cell Reports 2016. 14 140–151. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egdell RM, De Souza AI, Macleod KT. Relative importance of SR load and cytoplasmic calcium concentration in the genesis of aftercontractions in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovascular Research 2000. 47 769–777. ( 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00147-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miura M, Taguchi Y, Nagano T, Sasaki M, Handoh T, Shindoh C. Effect of myofilament Ca(2+) sensitivity on Ca(2+) wave propagation in rat ventricular muscle. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2015. 84 162–169. ( 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JC, Wang J, Son MJ, Woo SH. Shear stress enhances Ca(2+) sparks through Nox2-dependent mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in rat ventricular myocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Cell Research 2017. 6 1121–1131. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.02.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosca MG, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure. Heart Failure Reviews 2013. 18 607–622. ( 10.1007/s10741-012-9340-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabassi A, Binno SM, Tedeschi S, Ruzicka V, Dancelli S, Rocco R, Vicini V, Coghi P, Regolisti G, Montanari A, et al Low serum ferroxidase I activity is associated with mortality in heart failure and related to both peroxynitrite-induced cysteine oxidation and tyrosine nitration of ceruloplasmin. Circulation Research 2014. 114 1723–1732. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302849) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabassi A, Dancelli S, Pattoneri P, Tirabassi G, Quartieri F, Moschini L, Cavazzini S, Maestri R, Lagrasta C, Graiani G, et al Characterization of myocardial hypertrophy in prehypertensive spontaneously hypertensive rats: interaction between adrenergic and nitrosative pathways. Journal of Hypertension 2007. 25 1719–1730. ( 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281de72f0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabassi A, Bouchard JF, Dumont EC, Girouard H, Le Jossec M, Lamontagne D, Besner JG, de Champlain J. Effect of antioxidant treatments on nitrate tolerance development in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Journal of Hypertension 2000. 18 187–196. ( 10.1097/00004872-200018020-00009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tse G, Yan BP, Chan YW, Tian XY, Huang Y. Reactive oxygen species, endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: the link with cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Frontiers in Physiology 2016. 7 313 ( 10.3389/fphys.2016.00313) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabassi A, Miragoli M. Altered mitochondrial metabolism and mechanosensation in the failing heart: focus on intracellular calcium signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017. 18 1487 ( 10.3390/ijms18071487) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertero E, Maack C. Calcium signaling and reactive oxygen species in mitochondria. Circulation Research 2018. 122 1460–1478. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.310082) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santulli G, Xie W, Reiken SR, Marks AR. Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. PNAS 2015. 112 11389–11394. ( 10.1073/pnas.1513047112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patron M, Raffaello A, Granatiero V, Tosatto A, Merli G, De Stefani D, Wright L, Pallafacchina G, Terrin A, Mammucari C, et al The mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU): molecular identity and physiological roles. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013. 288 10750–10758. ( 10.1074/jbc.R112.420752) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasenfuss G, Schillinger W, Lehnart SE, Preuss M, Pieske B, Maier LS, Prestle J, Minami K, Just H. Relationship between Na+-Ca2+-exchanger protein levels and diastolic function of failing human myocardium. Circulation 1999. 99 641–648. ( 10.1161/01.cir.99.5.641) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pieske B, Maier LS, Bers DM, Hasenfuss G. Ca2+ handling and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content in isolated failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circulation Research 1999. 85 38–46. ( 10.1161/01.res.85.1.38) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Calcium signaling in cardiac mitochondria. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2013. 58 125–133. ( 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.12.021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grieve DJ, Shah AM. Oxidative stress in heart failure. More than just damage. European Heart Journal 2003. 24 2161–2163. ( 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.10.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner S, Dybkova N, Rasenack EC, Jacobshagen C, Fabritz L, Kirchhof P, Maier SK, Zhang T, Hasenfuss G, Brown JH, et al Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2006. 116 3127–3138. ( 10.1172/JCI26620) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2000. 192 1001–1014. ( 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dey S, Sidor A, O'Rourke B. Compartment-specific control of reactive oxygen species scavenging by antioxidant pathway enzymes. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016. 291 11185–11197. ( 10.1074/jbc.M116.726968) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peoples JN, Saraf A, Ghazal N, Pham TT, Kwong JQ. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Experimental and Molecular Medicine 2019. 51 1–13. ( 10.1038/s12276-019-0355-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nickel AG, von Hardenberg A, Hohl M, Loffler JR, Kohlhaas M, Becker J, Reil JC, Kazakov A, Bonnekoh J, Stadelmaier M, et al Reversal of mitochondrial transhydrogenase causes oxidative stress in heart failure. Cell Metabolism 2015. 22 472–484. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campos JC, Queliconi BB, Bozi LHM, Bechara LRG, Dourado PMM, Andres AM, Jannig PR, Gomes KMS, Zambelli VO, Rocha-Resende C, et al Exercise reestablishes autophagic flux and mitochondrial quality control in heart failure. Autophagy 2017. 13 1304–1317. ( 10.1080/15548627.2017.1325062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. X-ROS signaling: rapid mechano-chemo transduction in heart. Science 2011. 333 1440–1445. ( 10.1126/science.1202768) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khairallah RJ, Shi G, Sbrana F, Prosser BL, Borroto C, Mazaitis MJ, Hoffman EP, Mahurkar A, Sachs F, Sun Y, et al Microtubules underlie dysfunction in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science Signaling 2012. 5 ra56 ( 10.1126/scisignal.2002829) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, Meethal SV, Potter KT, Kamp TJ, Valdivia HH, Haworth RA. Increased nitration of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in human heart failure. Circulation 2005. 111 988–995. ( 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156461.81529.D7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iribe G, Kaihara K, Yamaguchi Y, Nakaya M, Inoue R, Naruse K. Mechano-sensitivity of mitochondrial function in mouse cardiac myocytes. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2017. 130 315–322. ( 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2017.05.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartolak-Suki E, Imsirovic J, Parameswaran H, Wellman TJ, Martinez N, Allen PG, Frey U, Suki B. Fluctuation-driven mechanotransduction regulates mitochondrial-network structure and function. Nature Materials 2015. 14 1049–1057. ( 10.1038/nmat4358) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuznetsov AV, Javadov S, Guzun R, Grimm M, Saks V. Cytoskeleton and regulation of mitochondrial function: the role of beta-tubulin II. Frontiers in Physiology 2013. 4 82 ( 10.3389/fphys.2013.00082) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rostovtseva TK, Sheldon KL, Hassanzadeh E, Monge C, Saks V, Bezrukov SM, Sackett DL. Tubulin binding blocks mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel and regulates respiration. PNAS 2008. 105 18746–18751. ( 10.1073/pnas.0806303105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. VDAC inhibition by tubulin and its physiological implications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2012. 1818 1526–1535. ( 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.11.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gurnev PA, Queralt-Martin M, Aguilella VM, Rostovtseva TK, Bezrukov SM. Probing tubulin-blocked state of VDAC by varying membrane surface charge. Biophysical Journal 2012. 102 2070–2076. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monge C, Beraud N, Kuznetsov AV, Rostovtseva T, Sackett D, Schlattner U, Vendelin M, Saks VA. Regulation of respiration in brain mitochondria and synaptosomes: restrictions of ADP diffusion in situ, roles of tubulin, and mitochondrial creatine kinase. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2008. 318 147–165. ( 10.1007/s11010-008-9865-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaniv Y, Juhaszova M, Wang S, Fishbein KW, Zorov DB, Sollott SJ. Analysis of mitochondrial 3D-deformation in cardiomyocytes during active contraction reveals passive structural anisotropy of orthogonal short axes. PLoS ONE 2011. 6 e21985 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0021985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rog-Zielinska EA, O'Toole ET, Hoenger A, Kohl P. Mitochondrial deformation during the cardiac mechanical cycle. Anatomical Record 2019. 302 146–152. ( 10.1002/ar.23917) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheng ZH. Mitochondrial trafficking and anchoring in neurons: new insight and implications. Journal of Cell Biology 2014. 204 1087–1098. ( 10.1083/jcb.201312123) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lichter JG, Carruth E, Mitchell C, Barth AS, Aiba T, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF, Bridge JH, Sachse FB. Remodeling of the sarcomeric cytoskeleton in cardiac ventricular myocytes during heart failure and after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2014. 72 186–195. ( 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiological Reviews 2004. 84 431–488. ( 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Romero L, Trenor B, Ferrero JM, Starmer CF. Non-uniform dispersion of the source-sink relationship alters wavefront curvature. PLoS ONE 2013. 8 e78328 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0078328) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen TP, Qu Z, Weiss JN. Cardiac fibrosis and arrhythmogenesis: the road to repair is paved with perils. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2014. 70 83–91. ( 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.10.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schaper J, Froede R, Hein S, Buck A, Hashizume H, Speiser B, Friedl A, Bleese N. Impairment of the myocardial ultrastructure and changes of the cytoskeleton in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1991. 83 504–514. ( 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.504) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circulation Research 2011. 109 1327–1331. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilding JR, Joubert F, de Araujo C, Fortin D, Novotova M, Veksler V, Ventura-Clapier R. Altered energy transfer from mitochondria to sarcoplasmic reticulum after cytoarchitectural perturbations in mice hearts. Journal of Physiology 2006. 575 191–200. ( 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114116) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boateng SY, Belin RJ, Geenen DL, Margulies KB, Martin JL, Hoshijima M, de Tombe PP, Russell B. Cardiac dysfunction and heart failure are associated with abnormalities in the subcellular distribution and amounts of oligomeric muscle LIM protein. American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2007. 292 H259–H269. ( 10.1152/ajpheart.00766.2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ashrafian H, McKenna WJ, Watkins H. Disease pathways and novel therapeutic targets in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research 2011. 109 86–96. ( 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242974) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a