Abstract

Background/Aim: Azygos vein aneurysm (AVA) is a rare thoracic pathological entity that mimics a posterior mediastinal mass as well as a right paratracheal mass. Usually asymptomatic, AVA is often accidentally discovered during routine chest x-rays; however, depending on the aneurysm size and complications, some symptoms may be present. The aim of this paper is to report a case of idiopathic AVA and to discuss its aetiology, embryonic origin, symptoms, complications, diagnostic methods and treatments. Case Report: A 74-year-old female was investigated for diffuse thoracic pain and submitted to standard chest x-ray, which identified a right paratracheal, well-defined, homogenous opacity, considered to be part of the mediastinal shadow. The patient was further submitted to thoracic computed tomography, which confirmed the presence of a tumoral mass at the level of the right paratracheal area. The patient was submitted to surgery and the tumoral mass was resected; however, the tumor proved to be a completely thrombosed aneurism of the azygos vein arch. Conclusion: AVA is a rare pathology that must be taken into consideration during the differential diagnosis of right postero-superior mediastinal masses.

Keywords: Azygos vein aneurysm, resection, mediastinal mass

The first reported case of Azygos Vein Aneurysm (AVA) was by Osler in 1915 and was identified during autopsy (1), while Walker described the first case of azygos vein aneurysm in 1963 as an idiopathic lesion (2). AVA is a rare pathology, which poses significant problems concerning its diagnosis, due to its rarity. In most cases, AVA patients are asymptomatic, however, they may become symptomatic if larger lesions occur, presenting with external compression of adjacent organs (esophagus, superior or inferior cava vein, right main bronchus or trachea) (3). In addition, AVA patients are usually reported as isolated cases, therefore, the experience in terms of diagnosis and treatment remains scarce. Rare idiopathic cases of AVA have been described; however, most aneurysms are secondary to increased blood flow and blood pressure from a different pathology (4). In the literature, cases of AVA have been reported for patients between the ages of 19 and 70 years old (5), however, the youngest patient reported was a 3-month-old infant presenting with an AVA associated with massive pulmonary embolism (5).

The progression of an AVA is unknown and the management of its pathology is still being discussed. Neurogenic tumors are the most common posterior mediastinal masses and they account for 75% of primary posterior mediastinal malignancies (6). Other types of posterior mediastinal tumors described are cystic tumors, tumors present in lymph nodes and solitary pleural fibromas (7).

In our study we will present a case of a saccular azygos vein arch aneurysm with complete thrombosis, which appeared as a right postero-superior mediastinal mass, confirmed through histopathological examination.

Case Report

The 74-year-old female patient presented i) right posterior thoracic pain of medium intensity, ii) persistent cough and iii) mild dyspnea. Blood tests revealed the presence of mild anemia (hemoglobin level=10.7 g/dl) and modified blood gas levels with an increase in pressure of carbon dioxide but with no other significant changes. Respiratory function tests showed a minimal decrease in Forced Expiratory Volume in the first second (FEV1) and vital capacity (VC). Electrocardiography (ECG) revealed sinus tachycardia, probably due to the associated anemia. Transesophageal echocardiogram and cardiological examination provided the diagnosis of stage A heart failure (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) (8). Bronchoscopy did not show any abnormalities within the bronchial tree except for sings of chronic bronchitis and bronchiectasis.

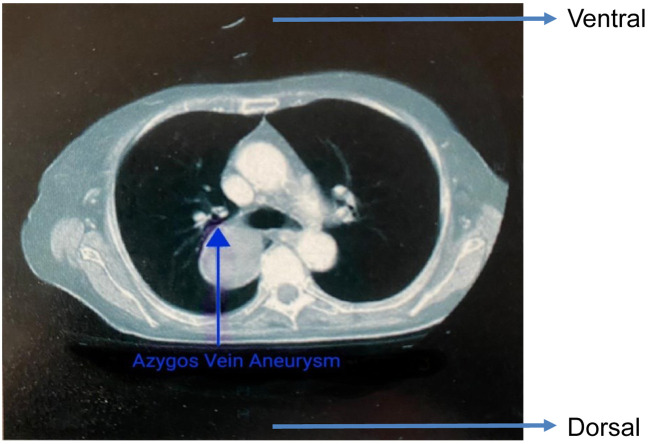

Standard chest x-ray and side view confirmed a 3×4 cm right hilar opacity, which seemed to be part of the mediastinal shadow (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Standard chest x-ray. Anterior-posterior view shows mediastinal mass (arrow).

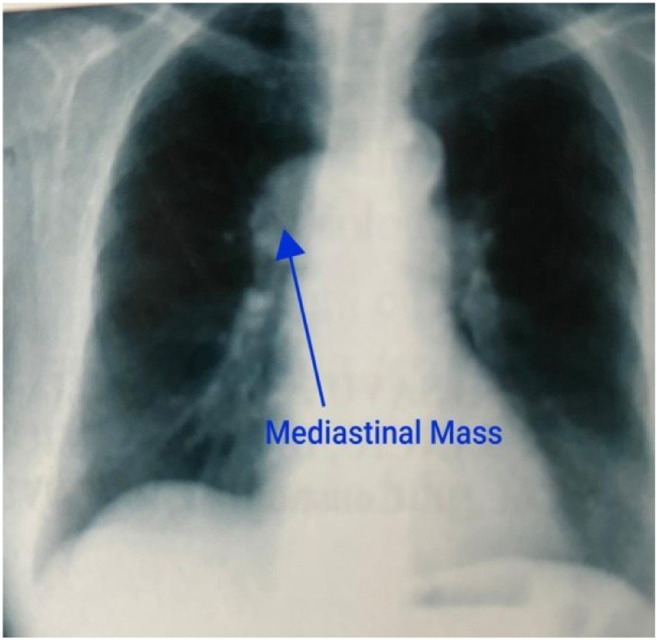

A thoracic and abdominal computed tomography with contrast enhancement was performed and revealed a homogenous, dense mass situated in the postero-superior mediastinum. The mass appeared to have a paravertebral development, and it was associated with minimum contrast substance enhancement, that appeared to be in the posterior segment of the right superior upper pulmonary lobe in contact with the posterior side of the right main bronchus and the T4 vertebral body, while no mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes were observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Thoracic computed tomography. Dorsal-ventral view shows the azygos vein aneurism.

By putting together imaging studies (thoracic computed tomography with standard chest x-ray and bronchoscopy) to understand the clinical presentation (persistent cough and thoracic pain), we settled on a presumptive diagnosis of a right postero-superior mediastinal mass.

Surgery was performed with the goal of removing the mass, using an anterolateral thoracotomy through the 4th intercostal space. Intraoperative exploration revealed a 3/6 cm well defined, purple, renitent, ovoid pseudotumoral mass located postero-superiorly. The mass proved to be part of the azygos vein arch, adherent to the right main bronchus and the superior vena cava.

Following a circumferential dissection and release from the adjacent anatomical structures, we observed that the mass was actually an azygos vein arch aneurysm. Initially, the mass appeared as a vascular tumor (azygos vein arch hemangioma); however, after ligating both the upper segment from the superior and inferior vena cava from the azygos vein and removing the tumor, we observed a venous dilation with intravascular thrombosis. Resection of the tumor en bloc with the azygos vein arch was safely performed with no intraoperative incidents or accidents. The postoperative evolution was favorable, and the patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day.

Histopathological studies revealed a cystic mass with fibrosclerous walls, including areas of hypertrophy with endoluminal septs and fibrohematic content (thrombus) in association with areas of re-permeabilization. Venous walls also presented hyperplasia with endothelial fibrosclerosis as well as sclerosis of the vascular media (Figure 3). Therefore, a final diagnosis of thrombosed azygos vein arch aneurysm was established.

Figure 3. Histological aspect of venous wall in the azygous vein aneurism.

Discussion

AVA has been described in both male and female patients, with a higher occurrence rate in women but with no significant difference when it comes to patients’ age or sex (9). The normal calibre of the azygos vein is lower than 5mm, thus, all cases presenting larger dimension of this structure are considered as AVA (10). Regarding the development of the azygos vein, during the 4th week of gestation venous blood is drained through the anterior and posterior cardinal veins, while a week later, the supracardinal veins are developed, later giving rise to the azygos vein. The azygos vein arch is formed from the posterior cardinal vein, which comes together with the supracardinal vein and drains into the superior vena cava. Therefore, the azygos vein arch represents the confluence of three different embryonic vessels: i) the right supracardinal vein (azygos vein), ii) the right posterior cardinal vein (azygos arch) and iii) the right anterior cardinal vein (11). From an architecture point of view, this confluence may represent a weak anatomic point that favours the appearance and development of an aneurysm (11). The azygos vein arch that drains into the superior vena cava (SVC) has a different embryonic origin compared to the azygos vein, which may also represent a weak point for the development of an aneurysm (12).

Anatomic variants of the inferior and superior cava system may also be favouring factors for AVA (13). Other anatomical associations with AVA described include a double inferior vena cava, a retro-aortic left renal vein and an azygos vein that continues as the inferior vena cava (13).

The etiology of azygos vein aneurysms is not fully known. One cause is thought to be the increase of blood pressure within the azygos vein, leading to a fusiform dilation. This appears in portal hypertension from liver cirrhosis, occlusion of the inferior vena cava, and global or right heart failure (4,14). There have also been also cases of AVA secondary to vascular tumors, such as hemangiomas, lymphangliomas or leiomiosarcomas belonging to the azygos vein (15). Sometimes, the increase of the blood pressure in the azygos vein is determined by the obstruction of the superior vena cava and may lead to the apparition of AVA, with a calibre that varies depending on the position of the patient and the respiratory cycle (16). Another cause of increased blood pressure in the azygos vein is determined by the thrombosis or aplasia of the inferior vena cava, resulting in a retrograde azygos vein aneurysm (17). Another cause for this pathology can appear during pregnancy due to the compression of the azygos vein and an increase of blood pressure within it (18).

A different cause of azygos vein aneurysm is represented by the pseudoaneurysm from trauma following either blunt lesions or catheterization of the azygos vein (19). Idiopathic AVA is another form of AVA considered by some authors to be congenital (20). There are particular situations when congenital AVA has a migratory character, moving from the posterior mediastinum to the right superior mediastinum (21).

Association between genetic malformation syndromes and azygos vein aneurysms have also been described, especially with the type IV Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a rare genetic disease affecting connective tissue, with the clinical type 4 being the vascular type (22). In this syndrome, the skin is thin, translucent, and associated with an increased visibility of the subcutaneous vascular pattern. Vascular walls suffer morphological modifications; therefore, they appear as thin structures predisposed to the apparition of aneurysms, vascular dissection, vascular rupture or arteriovenous fistulae. The genetic mutation responsible for this syndrome is COL3A1 (22).

Other causes suspected for AVA involve endothelial phlebo-hypertrophy (the smooth muscle hypertrophy to varying degrees, and an intima layer thickening with collagen breakdown and abnormal synthesis of proteins) or phlebosclerosis (thickening of venous wall with fibrosis) (23,24). Other authors consider the cause of AVA as a congenital weakness of the azygos vein arch or a series of degenerative changes in the venous wall due to quality issues of the connective tissue. Focal loss of normal components of the connective tissue within the venous wall is determined by either a congenital underdevelopment or by the loss of tissue that comes with aging. All of these could represent causes of azygos vein aneurysms (25).

Other authors consider that aplasia or hypoplasia of the inferior or superior vena cava may lead to azygos vein aneurysm. Standard acquired venous dilations (varicose veins) are characterized by the presence of subendothelial fibrosis while congenital venous dilations are defined by anomalies in the media layer of the vessel (26). In azygos vein aneurysms, the media layer is the most affected one – as opposed to acquired dilations, where there is fibrosis in the subendothelial space. Pathology examinations reveal that in AVA the muscular part of the media layer of the vein wall is atrophied (26). Other studies have stated that there is a thickening of the muscular layer in the venous wall associated with an inflammatory reaction surrounding the vascular adventitia (27).

In our case, pathology revealed diminished or absent media layer, as well as endothelial fibrosis in the intima layer. We did not discover an obvious cause for the apparition of AVA; therefore, we concluded that it was a sacular, idiopathic aneurysm with complete thrombosis that mimicked a mediastinal mass.

Some authors consider that aneurysms larger than 5 cm determine the apparition of symptoms, due to the compression of adjacent structures, such as oesophagus, bronchi, SVC, and pneumogastric nerve (28). Most frequent symptoms found are: i) dysphagia, ii) persistent cough, iii) heart palpitation and iv) chest thickness (12). There has also been a report of presyncopal symptoms as the only clinical manifestation in a patient with orthostatic hypotension (29). Other symptoms, such as wheezing, cough and persistent hiccups have been also described (28), While AVA is also considered to be caused by the irritation or compression of the vagus nerve (28).

Diagnosing an azygos vein aneurysm can be difficult, especially if it is associated with another thoracic pathology. In a previous case of AVA in a patient with esophageal cancer, this made the final diagnosis much more difficult to be established and it was discovered during exploratory thoracoscopy (30). Another association of AVA with pulmonary cancer was presented in a patient, who was diagnosed using transesophageal echography, which helped differentiate between an aneurysm and paratracheal mediastinal lymph nodes (31,32).

Most often, the preoperative diagnosis of sacular azygos vein aneurysms, especially in cases with associated complete thrombosis might be very difficult to establish, due to the similarity to other mediastinal masses (33). In our case, the differential diagnosis was done between: i) neurogenic tumor, ii) vascular tumor (leioangiosarcoma), iii) paratracheal and hilar lymph nodes, and iv) bronchogenic cyst. Some other authors consider that in the case of AVA with complete thrombosis it is impossible to differentiate from other mediastinal masses, similar to our patient (34). In the case we presented, diagnosis was made intraoperatively and further confirmed by pathology examination.

Another diagnostic challenge is identifying AVA as such in cases of an azygos lobe present (35). In order to increase the diagnostic accuracy, some authors have proposed using a dynamic computed tomography in combination with magnetic resonance imaging angiography (36). Others advocate for the use of transesophageal Doppler, which can show the presence or absence of blood flow (37) inside the AVA. In some cases, even a standard thoracic x-ray can reveal a mass, which is part of the mediastinal shadow, presenting different sizes during respiratory movements and Valsalva maneuver, and suggesting in this way the presence of an AVA (38,39).

The most common imaging study performed in AVA is still the thoracic computed tomography. To this end some authors have suggested using dynamic or enhanced multidetector thoracic computed tomography, especially in thrombosed aneurysms (14). Other authors consider dynamic computed tomography as being useless in cases of AVA with complete thrombosis or with diminished and turbulent blood flow. It must be mentioned that dynamic magnetic resonance imaging combined with thoracic CT scan is useful in establishing the nature of the mass and origin of vascular lesions, while also identifying the vascular connections with adjacent structures (11).

Several important complications of AVA have been cited in the literature, such as: i) compression of adjacent organs, ii) pulmonary embolism, iii) secondary thrombosis of pulmonary arteries, iv) aneurysm dissection, and v) aneurysm rupture or veno-arterial fistulae (22). As for the therapeutic strategy of AVA, there is no established conduit, or knowledge concerning the best approach for asymptomatic cases. When the aneurysm is small, computed tomography follow-up and conservative treatment is recommended. Some authors do not recommend surgery for asymptomatic AVA due to the risk of pulmonary embolism during the intraoperative manipulation of the lesion (4,9,38). Other authors agree that treatment of AVA should be conservative, and surgery should be reserved for complicated cases or when a clear diagnosis is not possible (18,40). In our case, surgery was performed with the suspicion of a mediastinal tumoral mass, while the diagnosis of AVA was made intraoperatively and confirmed later on by the histopathological studies. Endovascular treatments have also been suggested. These include: i) endoluminal prosthetics, such as endovenous stents (41), ii) coil embolization (42), iii) amplatzer vascular plug or iv) aneurysmal thrombolysis. In cases with portal hypertension or inferior vena cava occlusion, aneurysm resection represents a contraindication (26).

The only surgical resection proposed for AVA is idiopathic AVA or symptomatic cases, which should be performed using either through open or video assisted thoracic surgery. Conservative treatment and oral anticoagulant treatment may be used in selected cases but, so far, there is no clear guideline or therapeutic program for surgical or endovascular treatment. Moreover, in complex cases associated with pulmonary thrombosis, surgery may be performed using extracorporeal circulation (19).

In conclusion, AVA is a rare pathology that must be taken into consideration during the differential diagnosis of right postero-superior mediastinal masses. It should be noted that the final diagnosis might be hard to be establish preoperatively. In cases of AVA with complete thrombosis, surgery is recommended and must be performed with extreme care in order to prevent intraoperative embolism. For a correct diagnosis invasive testing is not required, while in cases of diagnostic uncertainty an exploratory thoracoscopy may be performed. When it comes to the type of surgical approach, either open surgery or video assisted thoracic surgery might be considered, depending on the local status and size of the aneurysm.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this study.

Authors’ Contributions

CS, AM performed surgical procedures, IB prepared the manuscript and performed data analysis, and NB advised about the surgical oncology procedure, revised the final draft of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the project entitled “Multidisciplinary Consortium for Supporting the Research Skills in Diagnosing, Treating and Identifying Predictive Factors of Malignant Gynecologic Disorders”, project number PN-III-P1-1.2-PCCDI2017-0833.

References

- 1.Osler W. Remarks on cerebro-spinal fever in camps and babracks. Br Med J. 1915;1(2822):189–190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2822.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker WA. Aneurysm of the azygos vein, etiology undetermined. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;90:575–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurihara C, Kiyoshima M, Asato Y, Suzuki H, Kitahara M, Satou M, Amemiya R. Resection of an azygos vein aneurysm that formed a thrombus during a 6-year follow-up period. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):1008–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gnanamuthu BR, Tharion J. Azygos vein aneurysm-a case for elective resection. Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17(1):62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi J, Song J, Huh J, Kang IS, Yang JH, Jun TG. Complicated azygos vein aneurysm in an infant presenting with acute pulmonary thromboembolism. Korean Circ J. 2016;46(2):264–267. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.2.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haithcock BE, Zagar TM, Zhang L, Stinchcombe TE. Diseases of the pleura and mediastinum. Abeloff's Clin Oncol. 2014;e4:1193–1206. doi: 10.1016/B978-1-4557-2865-7.00073-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirvu A, Angelescu D, Savu C. Localized fibrous tumor of the pleura an unusual cause of severe hypoglycaemia. Case report. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2016;120(3):628–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed A. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Chronic Heart Failure Evaluation and Management guidelines: relevance to the geriatric practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):123–126. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.51020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santamaria NA, Diez JMG, Fernandez, Maria JP. Azygos vein aneurysm forming a mediastinal mass. Arch Bronconeumol. 2006;42(8):410–412. doi: 10.1016/S1579-2129(06)60556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandato Y, Pecoraro C, Gagliardi G, Tecame M. Azygos and hemiazygos continuation: An occasional finding in emergency department. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14(9):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choo JY, Lee KY, Oh SJ, Je BK, Lee SH, Kim BH. Azygos vein aneurysm mimicking paratracheal mass: dynamic magnetic resonance imaging findings. Balkan Med J. 2013;30(1):111–115. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2012.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton K, KiaNoury D. Incidental azygos vein aneurysm masquerading as a mediastinal mass. Chest. 2012;142(4):979A. doi: 10.1378/chest.1388336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onoda K, Shomura Y, Komada T. Double inferior vena cava with azygos continuation and retroaortic left renal vein associated with juxtarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Ann Vasc Dis. 2018;11(1):123–126. doi: 10.3400/avd.cr.17-00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda Y, Tokuno J, Shoji T, Huang CL. An azygos vein aneurysm resected by video-assisted thoracic surgery after preoperative evaluation of multidetector computed tomography. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(1):135–136. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo B, Guo D, Fu W, Shi Z. A giant azygos venous aneurysm caused by the resection of hemangioma. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2014;2(3):328. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galie N, Vasile R, Savu C, Petreanu C, Grigorie V, Tabacu E. [Superior vena cava syndrome-surgical solution-case report] Chirurgia (Bucur) 2010;105(6):835–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammad K, Bhaskar N, Siddiqui M. Idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm mimicking a mediastinal mass. case report and review of literature. J Med Cases. 2013;4(5):292–295. doi: 10.4021/jmc1127w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko SF, Huang CC, Lin JW, Lu HI, Kung CT, Ng SH, Wan YL, Yip HK. Imaging features and outcomes in 10 cases of idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(3):873–878. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura Y, Nakano K, Nakatani H, Fukuda T, Honda K, Homma N. Surgical exclusion of a thrombosed azygos vein aneurysm causing pulmonary embolism. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133(3):834–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichiki Y, Hamatsu T, Suehiro T, Koike M, Tanaka F, Sugimachi K. An idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm mimicking a mediastinal mass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(1):338–340. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He J, Mao H, Li H, Zhu B, Chen J, Zhou Z. A case of idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm and review of the literature. J Thorac Imaging. 2012;27(4):W91–W93. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e318217272d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Souza ES, Williams DM, Deeb GM, Cwikiel W. Resolution of large azygos vein aneurysm following stent-graft shunt placement in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29(5):915–919. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-4189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bush RG, Bush P. Aneurysms of the superficial venous system: classification and treatment. Veins Lymphat. 2014;3(2) doi: 10.4081/vl.2014.4503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irwin C, Synn A, Kraiss L, Zhang Q, Griffen MM, Hunter GC. Metalloproteinase expression in venous aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(5):1278–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lev M, Saphir O. Endophlebohypertrophy and phlebosclerosis. II. The external and common iliac veins. Am J Pathol. 1952;28(3):401–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risau W. Philadelphia. Karger. 1991. Vasculogenesis, angiogenesis and endothelial cell differentiation during embryonic development. In: Feinberg RN, Sheror GK, Auerbach R, eds. The development of the vascular system; pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki Y, Kaji M, Hirose S, Ohtsubo S. Azygos vein aneurysm resection concomitant with heart valve repair via right thoracotomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;23(6):982–984. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivw252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irurzun J, de Espana F, Arenas J, Garcia-Sevila R, Gil S. Successful endovascular treatment of a large idiopathic azygos arch aneurysm. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(8):1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Person TD, Komanapalli CB, Chaugle H, Schipper PH, Sukumar MS. Thoracoscopic approach to the resection of an azygos vein aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(1):230–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bobbio A, Miranda J, Gossot D, Perniceni T, Grunenwald D. Azygos vein aneurysm as a diagnostic pitfall. The role of thoracoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(9):1049–1050. doi: 10.1007/s004640000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obeso A, Souilamas R. Unexpected intraoperative finding of azygos vein aneurysm mimicking a metastatic lymph node. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54(4):217. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato H, Nakajima M, Fukuchi M, Miyazaki T, Manda R, Kimura H, Faried A, Sohda M, Fukai Y, Masuda N, Tsukada K, Kuwano H. Serum p53 antibodies in drainage blood from the azygos vein in patients with esophageal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2005;25(5):3231–3235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaguchi M, Hanazaki K, Nakamura T, Koike S, Shimizu T, Kumeda S, Amano J. Idiopathic saccular aneurysm of the azygos vein. J Card Surg. 1999;14(3):178–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.1999.tb00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez MA, Delhommais A, Presicci PF, Besson M, Roger R, Alison D. Partial thrombosis of an idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm. Br J Radiol. 2004;77(916):342–343. doi: 10.1259/bjr/28611372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cordoba Rovira SM, Guedea MA, Salvador AI, Elias AJ. Saccular aneurysm of the azygos vein in a patient with azygos accessory fissure. Radiologia. 2015;57(2):167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallegoa M, Mirapeix RM, Castaner E, Domingo C, Mata JM, Marin A. Idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm: a rare cause of mediastinal mass. Thorax. 1999;54(7):653–655. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe A, Kusajima K, Aisaka N, Sugawara H, Tsunematsu K. Idiopathic saccular azygos vein aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65(5):1459–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iordache A, Stevenage MB, Sultan J, Carne A. A case of idiopathic azygos vein aneurysm. Int J Case Rep Images. 2015;6(12):786–788. doi: 10.5348/ijcri-201538-CL-10093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehta M, Towers M. Computed tomography appearance of idiopathic aneurysm of the azygos vein. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1996;47(4):288–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohajeri G, Hekmatnia A, Ahrar H, Hekmatnia F, Basiratnia R. Azygos vein aneurysm as a posterior mediastinal mass discovered after minor chest trauma. Iran J Radiol. 2014;11(1):e7467. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.7467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Favelier S, Estivalet L, Pottecher P, Loffroy R. Successful endovascular treatment of a large azygos vein aneurysm with stent-graft implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(4):1455. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tujo CA, Jesinger RA. Azygous vein aneurysm (AVA): A case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(2):TD03–TD05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/20945.9421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]