Abstract

Background:

Transoral thyroid surgery represented by the da Vinci system is attracted attention and performed by several institutions. However, the current available da Vinci system still has some limitations to be improved for transoral thyroid surgery including high cost of equipment and expendables, larger diameter scope and instruments and no tactile sensation. It triggered us interest in more easily available robotic scope holder. Soloassist II (AktorMed GmbH, Barbing, Germany) is an active endoscope holder system which is controlled by a joystick. It has total six joints: three joints which are controlled by computer, one is controlled by manual and two act as a gimbal joint following the movement of the main body.

Materials and Methods:

We tried transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using Soloassist II (AktorMed GmbH, Barbing, Germany) in December 2017 in our hospital.

Results:

We successfully performed four thyroid lobectomies in four patients with Soloassist II. We refined and described surgical procedures in each step using video clips. It provided an excellent vibration-free stable surgical view which enabled fatigue-free work, without shaking or tilting the horizon. The surgeon could perform transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery with only one assistant surgeon. Docking and preparation time for Soloassist was within 10 min in all four patients. The setup and dismantling could be performed parallel to the usual workflow. No complication was reported by any patient.

Conclusions:

The robotic scope holder (Soloassist II) seems to be safe and feasible equipment for performing transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery. Several possible advantages could be expected with this robotic scope holder.

Keywords: Minimally invasive surgical procedure, thyroid, thyroidectomy, transoral, transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach, transoral thyroidectomy

INTRODUCTION

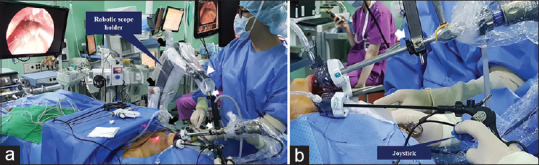

Transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery, as a concept of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, is the surgical technique for applying an endoscope through the oral cavity and performing thyroidectomy only with oral mucosal incision and without any visible skin incision.[1,2] Since Anuwong reported the successful results in 60 patients, transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery became to be known widely and used increasingly by several head-and-neck surgeons around the world.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8] Transoral thyroid surgery represented by the da Vinci system (Intuitive Surgical, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) is also attracted attention and performed by some institutions.[9,10] However, the current available da Vinci system still has some limitations to be improved for transoral thyroid surgery including high cost of equipment and expendables, larger diameter scope and instruments, the risk of burns due to the higher heat emitted by the scope light, being cumbersome to change instruments and no tactile sensation. It triggered us interest in more easily available robotic scope holder. Soloassist (AktorMed GmbH, Barbing, Germany) is an active endoscope holder system which was developed for abdominal surgery and increasingly is used by general surgeon, urologist and gynaecologist.[11] It has total six joints: three joints which are controlled by computer, one is controlled by manual and two act as a gimbal joint following the movement of the main body.[12] The manipulator is consisted of carbon fibre-reinforced plastic segments which are controlled by a joystick.[13] The main body of Soloassist can be simply installed to the side rail of operating table using quick-coupling device, and joystick is designed to fit and easily positioned to almost commercially available laparoscopic instruments using a clamp mount [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a) An active endoscope holder system which has total six joints: three joints controlled by computer (black arrow), one controlled by manual (white arrowhead) and two act as a gimbal joint following the movement of the main body (white arrow). (b) Joystick is designed to fit and easily positioned to almost commercially available laparoscopic instruments using a clamp mount

The purpose of this study is to investigate the feasibility and safety of robotic scope holder (Soloassist II) for performing transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

We reviewed the medical records of patients who underwent transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using Soloassist II (AktorMed GmbH, Barbing, Germany) in December 2017 in our hospital. All patients were operated on in the same manner by the same surgeon. The inclusion criteria were (1) no surgical treatment of the head and neck before hospitalisation; (2) consent to use the robotic scope holder for performing transoral thyroid surgery; (3) a thyroid cancer without an extrathyroidal extension or lymph node metastasis on pre-operative ultrasonography; (4) a suspected or confirmed thyroid cancer <2 cm in diameter on the mid/lower lobe or <1 cm in diameter on the superior lobe and (5) a benign tumour <8 cm in diameter. Our Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Surgical technique

The patient was placed in the supine position with a pillow under the back for allowing the neck was slightly extended. We attached Soloassist to the operation table on the right side. Joystick, joint and camera support are autoclavable and the main body itself is covered by a sterile single-use drape. The oral cavity and anterior neck were disinfected using a usual povidone/water solution. The usual draping was done so that the upper lip is sufficiently exposed superiorly and the sternal notch inferiorly. The operating team consisted of three people: the operator, an assistant surgeon who helped to manage the Soloassist and maintain the working cavity during surgery and a scrub nurse. The surgeon was seated on chair with armrest beside the patient's head. The assistant surgeon was positioned to the right or left side of the patient. The scrub nurse stood to the left of the table near the patient's feet. The endoscopic equipment and monitor were located beyond the patient's feet [Figure 1].

We made a 2 cm-sized midline incision in the vestibule and two lateral incisions on the buccal mucosa near the first molar tooth. The working space was made and widened along the subplatysmal plane to the sternal notch inferiorly and to both sternocleidomastoid muscles laterally as we described in the previous report.[7] A 10-mm diameter cannula (for endoscope) was positioned through the midline incision site and inserted, and two 5-mm diameter cannulas (for laparoscopic instruments) were positioned through each lateral incision. Carbon dioxide gas was insufflated at a pressure of 5–6 mmHg to maintain the working space. For manual positioning of Soloassist, at the push of a button which is located on the end of robotic arm, the surgeon can move and pull the arm into the required position. When the button released, the arm is locked and remained in the set position. After adjusting the ‘trocar point’ that defines the axis of motion, surgeon can control the movement of endoscope through a joystick positioned on the instrument. Endoscopic operative procedures were performed step by step routinely as described in the previous report: separation of the strap muscle from the thyroid gland, division of the upper pole and isthmus, dissection of the retrothyroid area (identifying and preserving the parathyroid gland and recurrent laryngeal nerve) and removal of specimen and reapproximation of both strap muscles [Video 1].[7] After the endoscopic procedures were completed, the arm was hung onto the trolley and away from operation field. The three oral incision sites were closed using absorbable sutures, and a pressure dressing was placed around the chin and neck using an elastic bandage. Post-operative management followed routine protocol.[7]

RESULTS

We performed four thyroid lobectomies in four patients. The radiological and pathological features of all patients are summarised in Table 1. The operative details, post-operative progress notes, complications and changes in voice parameters are summarised in Table 2. No sensory change around the lower lip was reported by any patient. No patient exhibited recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. No patient developed hypocalcaemia. No patient developed a wound infection. No visible scar or dimpling was evident on the neck of any patient.

Table 1.

Radiological and pathological features of patients who underwent transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using robotic laparoscope holder (n=4)

| Case | Sex/age (years) | Pre-operative cytopathology (Bethesda system) | Pre-operative ultrasonography | Post-operative pathology | Other | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (cm) | Number of tumour | Location | ETE | Lymph node metastasis | Diagnosis | Margin | ETE | Number of positive node | ||||

| 1 | Female/28 | V | 2.7 | 1 | Left | - | - | FA | - | - | 0 | |

| 2 | Female/43 | V | 0.35 | 1 | Right | - | - | PTC | - | - | 0 | |

| 3 | Female/45 | VI | 0.5 | 1 | Left | - | - | PTC | - | - | 0 | |

| 4 | Female/47 | VI | 0.57 | 1 | Left | - | - | PTC | - | - | 0 | |

ETE: Extrathyroid extension, FA: Follicular adenoma, PTC: Papillary thyroid cancer

Table 2.

Operative details, post-operative progress notes and complications of transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy using robotic laparoscope holder (n=4)

| Case | Operation | Progress notes | Complications | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extent of surgery | CND | Docking time (min) | Total operation time (min) | Diet (POD) | Drain | Hospital day (POD) | Stitches out (POD) | Sensory change | Vocal cord palsy | Hypocalcaemia | Other | |

| 1 | Lobectomy | - | <10 | 120 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | Lobectomy | - | <10 | 190 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | Lobectomy | - | <10 | 110 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 15 | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | Lobectomy | - | <10 | 90 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | - | - | - | - |

CND: Central node dissection, POD: Post-operative day

DISCUSSION

Controlling and static holding of endoscope is precise and delicate work to perform endoscopic surgery and is also tiresome work for assistant surgeon. Although we have adopted Soloassist to transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery in only four patients, several possible advantages could be expected with this robotic scope holder. First, it provided excellent surgical view which did not depend on the endoscopic assistant as surgeon could determine the image by himself. Second, it provided vibration-free stable surgical view which enabled fatigue-free work, without shaking or tilting the horizon. Third, surgeon could perform transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery with only one assistant surgeon. The assistant surgeon was thus freed up to focus on more exacting tasks and had more time to follow operator's explanations more attentively.

In addition, docking and preparation time for Soloassist was within 10 min in all four patients. It could be attached directly on the operating table and covered with a sterile drape while the patient was being prepared for surgery. The setup and dismantling could be performed parallel to the usual workflow.

In the first case, the surgeon was uncomfortable with the joystick to control the direction of the scope at the beginning of the operation, however, was able to adjust it without difficulty from the second case. Operators who are using robotic holders for the first time are unlikely to have long-running curves. It took 190 min to complete thyroid lobectomy in one patient because we had trouble in identifying and preserving recurrent laryngeal nerve. Thyroid gland was developed posteriorly that caused trouble in identifying recurrent laryngeal nerve. The time required for docking the robotic holder was <10 min and it seemed that there was no problem in securing the operative field using holder.

CONCLUSIONS

The robotic scope holder (Soloassist II) seems to be safe and feasible equipment for performing transoral endoscopic thyroid surgery.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (No. NRF-2014R1A2A2A03004802).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Video available on: www.journalofmas.com

REFERENCES

- 1.Moris DN, Bramis KJ, Mantonakis EI, Papalampros EL, Petrou AS, Papalampros AE, et al. Surgery via natural orifices in human beings: Yesterday, today, tomorrow. Am J Surg. 2012;204:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anuwong A. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach: A series of the first 60 human cases. World J Surg. 2016;40:491–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chai YJ, Chung JK, Anuwong A, Dionigi G, Kim HY, Hwang KT, et al. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma: Initial experience of a single surgeon. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2017;93:70–5. doi: 10.4174/astr.2017.93.2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dionigi G, Bacuzzi A, Lavazza M, Inversini D, Boni L, Rausei S, et al. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy: Preliminary experience in Italy. Updates Surg. 2017;69:225–34. doi: 10.1007/s13304-017-0436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu J, Luo Y, Chen Q, Lin F, Hong X, Kuang P, et al. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy: Review of 81 cases in a single institute. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28:286–91. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jitpratoom P, Ketwong K, Sasanakietkul T, Anuwong A. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach (TOETVA) for Graves’ disease: A comparison of surgical results with open thyroidectomy. Gland Surg. 2016;5:546–52. doi: 10.21037/gs.2016.11.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JO, Sun DI. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy: Our initial experience using a new endoscopic technique. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:5436–43. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5594-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dionigi G, Chai YJ, Tufano RP, Anuwong A, Kim HY. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy via a vestibular approach: Why and how? Endocrine. 2018;59:275–9. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1451-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim HY, Chai YJ, Dionigi G, Anuwong A, Richmon JD. Transoral robotic thyroidectomy: Lessons learned from an initial consecutive series of 24 patients. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:688–94. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5724-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richmon JD, Kim HY. Transoral robotic thyroidectomy (TORT): Procedures and outcomes. Gland Surg. 2017;6:285–9. doi: 10.21037/gs.2017.05.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillen S, Pletzer B, Heiligensetzer A, Wolf P, Kleeff J, Feussner H, et al. Solo-surgical laparoscopic cholecystectomy with a joystick-guided camera device: A case-control study. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:164–70. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohmura Y, Nakagawa M, Suzuki H, Kotani K, Teramoto A. Feasibility and usefulness of a joystick-guided robotic scope holder (Soloassist) in laparoscopic surgery. Visc Med. 2018;34:37–44. doi: 10.1159/000485524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristin J, Geiger R, Kraus P, Klenzner T. Assessment of the endoscopic range of motion for head and neck surgery using the SOLOASSIST endoscope holder. Int J Med Robot. 2015;11:418–23. doi: 10.1002/rcs.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.