Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic in March 2020. Several prophylactic vaccines against COVID-19 are currently in development, yet little is known about people’s acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Methods

We conducted an online survey of adults ages 18 and older in the United States (n = 2,006) in May 2020. Multivariable relative risk regression identified correlates of participants’ willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine (i.e., vaccine acceptability).

Results

Overall, 69% of participants were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Participants were more likely to be willing to get vaccinated if they thought their healthcare provider would recommend vaccination (RR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.49–2.02) or if they were moderate (RR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.16) or liberal (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.07–1.22) in their political leaning. Participants were also more likely to be willing to get vaccinated if they reported higher levels of perceived likelihood getting a COVID-19 infection in the future (RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.09), perceived severity of COVID-19 infection (RR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.04–1.11), or perceived effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine (RR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.40–1.52). Participants were less likely to be willing to get vaccinated if they were non-Latinx black (RR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.74–0.90) or reported a higher level of perceived potential vaccine harms (RR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92–0.98).

Conclusions

Many adults are willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine, though acceptability should be monitored as vaccine development continues. Our findings can help guide future efforts to increase COVID-19 vaccine acceptability (and uptake if a vaccine becomes available).

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Vaccine, Adults

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization declared that coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) can be characterized as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), with cases ranging from individuals who are asymptomatic to those who experience severe respiratory distress, pneumonia, and death [2]. As of August 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused more than 20 million cases and 700,000 deaths worldwide [1]. The United States (US) has experienced the largest burden of COVID-19 of any country up to this point, with more than five million cases and 160,000 deaths thus far [1].

Protective behaviors are key to managing pandemics [3], and vaccination could be a key protective behavior for COVID-19. Several prophylactic vaccines against COVID-19 are currently in development across multiple countries [4], [5]. Estimated timelines for licensure of a COVID-19 vaccine differ, though there is some speculation that licensure could occur in 2021 [6]. With vaccine development underway, it becomes important to start examining people’s acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine. During the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, early estimates of vaccine acceptability suggested that about 50%-64% of adults in the US intended to get the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccine [7], [8], [9]. However, little is currently known about people’s acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine or factors that affect acceptability. Such information is useful for generating informed projections of what vaccine uptake might be in the future and also identifying strategies for improving acceptability (and uptake following vaccine availability). The current study examined acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among a national sample of adults in the US.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study about COVID-19 with adults in the US in May 2020 (about two months after COVID-19 was declared a pandemic1). Eligibility criteria included being age 18 or older and currently living in the US. We recruited all participants from an online survey panel accessed through a survey company, SSRS (Glen Mills, PA). The online panel is a national opt-in panel, and its members are invited to complete self-administered online surveys on a regular basis in exchange for incentives from the survey company.

We utilized a convenience sample from this online panel for this study. Panel members who were potentially eligible received an email invitation from SSRS to participate. Panel members who were interested in the study proceeded via weblink to a brief online screener survey that collected demographic information to determine study eligibility (i.e., data on age and US residence determined eligibility status). Panel members who were confirmed eligible then provided informed consent prior to completing their online study survey. A total of 2,006 adults from all 50 states (plus the District of Columbia) participated in our study and completed a survey. The mean time of survey completion was about 23 min, and participants received a standard incentive from SSRS for completing the survey. (e.g., a $5 gift card). The Institutional Review Board at “The Ohio State University” determined this study was exempt from review.

2.2. Measures

COVID-19 Vaccination. A copy of the study survey is provided in Appendix A. We developed survey items on vaccination based on past research involving vaccination behaviors [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Prior to survey items about a COVID-19 vaccine, participants were provided with multiple informative statements about COVID-19 infection and a statement that a vaccine is in development. Survey instructions then told participants to imagine that a vaccine will become available when answering items about COVID-19 vaccination. We assessed participants’ vaccine acceptability by asking how willing they would be to get a COVID-19 vaccine if it was free or covered by health insurance. Response options included “definitely not willing,” “probably not willing,” “not sure,” “probably willing,” and “definitely willing.” For our primary outcome, we dichotomized these responses into “willing” (definitely or probably willing) or “not willing” (all other responses). Participants then indicated the most they would pay out-of-pocket to get vaccinated against COVID-19 ($0, $1-$19, $20-$49, $50-$99, $100-$199, or $200+ ).

We then examined factors that would matter in participants’ decisions about whether or not to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Participants were asked to imagine that they are considering whether or not to get a COVID-19 vaccine. The survey then presented participants with a total of 11 factors, and participants indicated whether each factor would matter or would not matter to them in deciding about vaccination. Each factor was treated as a separate binary outcome (i.e., “would matter” or “would not matter”). Factors were presented to participants one at a time and in random order.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs. We assessed participants’ knowledge about COVID-19 infection by calculating the proportion of five knowledge items answered correctly (possible range = 0–1). The survey also included attitude and belief items about COVID-19 infection: perceived likelihood of getting a COVID-19 infection in the future (1 item, possible range = 1–4); perceived severity of a COVID-19 infection (1 item, possible range = 1–4); and perceived stigma associated with COVID-19 infection (4 items, α = 0.75, possible range = 1–5). Attitude and belief items about COVID-19 vaccination included: perceived effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine (1 item, possible range = 1–4); perceived potential harms of a COVID-19 vaccine (1 item, possible range = 1–5); and perceived unavailability of a COVID-19 vaccine (i.e., difficulty in finding a clinic to get vaccinated; 1 item, possible range = 1–5). The survey also assessed participants’ self-efficacy to engage in protective behaviors against COVID-19 (1 item, possible range = 1–5) and perceived positive social norms of protective behaviors against COVID-19 in their community (1 item, possible range = 1–5). “Protective behaviors” were described in the survey as things people can do to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 infection. We coded each attitude and belief variable so that higher values indicate greater levels of that construct.

Demographic and Health-Related Characteristics. The survey assessed a range of demographic and health-related characteristics (Table 1 ). We used information on county of residence and 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCs) [15] to classify each participant as living in an “urban” (RUCCs of 1–3) or “rural” (RUCCs of 4–9) county. We examined if participants had one or more underlying medical conditions that would put them at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19 (chronic lung disease, asthma, serious heart conditions, being immunocompromised, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, or body mass index of 40 or higher) [16]. We calculated body mass index based on participants’ self-reported height and weight. For the other medical conditions, participants indicated which conditions (from a predefined list) a doctor or other healthcare provider had ever told them they have, with participants having the ability to select multiple conditions if needed. The survey assessed if participants had ever been tested for COVID-19 infection, had a personal history of COVID-19 infection, and had a history of COVID-19 infection among their family members and friends. We also assessed if participants thought their healthcare provider would recommend that they get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Table 1.

Demographic and health-related characteristics of participants (n = 2,006).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 868 (43) |

| Female | 1122 (56) |

| Other | 16 (1) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–29 | 313 (16) |

| 30–49 | 657 (33) |

| 50–64 | 532 (27) |

| 65 and older | 504 (25) |

| Race / ethnicity | |

| White, non-Latinx | 1347 (67) |

| Black, non– Latinx | 240 (12) |

| Other race, non– Latinx | 178 (9) |

| Latinx | 241 (12) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 532 (27) |

| Married/civil union or living with partner | 1016 (51) |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 458 (23) |

| Education level | |

| Less than high school degree | 105 (5) |

| High school degree | 589 (29) |

| Some college | 629 (31) |

| College degree or more | 683 (34) |

| Household income | |

| Less than $50,000 | 1058 (53) |

| $50,000 to $89,999 | 527 (26) |

| $90,000 or more | 421 (21) |

| Political leaning | |

| Liberal | 503 (25) |

| Moderate | 850 (42) |

| Conservative | 653 (33) |

| Religiosity | |

| Not at all or slightly important | 715 (36) |

| Fairly, very, or extremely important | 1291 (64) |

| Sexual identity | |

| Straight | 1837 (92) |

| Other | 169 (8) |

| Urbanicitya | |

| Rural | 276 (14) |

| Urban | 1722 (86) |

| Region of residence | |

| Northeast | 380 (19) |

| North Central | 441 (22) |

| South | 767 (38) |

| West | 418 (21) |

| Health-Related Characteristics | |

| Health insurance | |

| None | 246 (12) |

| Private insurance | 830 (41) |

| Public insurance | 930 (46) |

| Underlying medical condition | |

| No | 1285 (64) |

| Yes | 721 (36) |

| Ever tested for COVID-19 | |

| No | 1771 (88) |

| Yes | 235 (12) |

| Personal history of COVID-19 diagnosis | |

| No | 1932 (96) |

| Yes | 74 (4) |

| Family member/friend ever diagnosed with COVID-19 | |

| No | 1712 (85) |

| Yes | 294 (15) |

| Think healthcare provider would recommend COVID-19 vaccine | |

| No | 327 (16) |

| Yes | 1679 (84) |

Note. Percents may not sum to 100% due to rounding. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Data on county of residence were not available for eight participants.

2.3. Data analysis

We first calculated descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies, means) for all variables. We used relative risk regression models with robust standard errors to identify correlates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability [17], as measured by participants’ willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccine if it was free or covered by health insurance. We entered all variables with p < 0.20 in bivariate analyses into an initial multivariable model. We then used a backward selection procedure that retained variables with p < 0.10 to create a final multivariable model. Regression models produced relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Lastly, we examined factors that would matter to participants in deciding about getting a COVID-19 vaccine. In doing so, we compared participants who were willing to get vaccinated to those who were not willing on each potential factor using chi-square tests with the Bonferroni adjustment to account for multiple testing. Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and all statistical tests were two-tailed.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Most participants were non-Latinx white (67%), had at least some college education (65%), and lived in an urban county (86%). Just over half of participants were female (56%), married/in a civil union or living with a partner (51%), and reported an annual household income of less than $50,000 (53%) (Table 1). The age distribution of participants included 16% who were ages 18–29, 33% who were ages 30–49, 27% who were ages 50–64, and 25% who were ages 65 and older. About 25% of participants indicated their political leaning as liberal, with 42% indicating moderate and 33% indicating conservative. Most participants had some type of health insurance (87%) and thought their healthcare provider would recommend they get vaccinated against COVID-19 (84%). Only 12% of participants had ever been tested for COVID-19 infection, with 4% indicating a personal history of COVID-19 infection and 15% indicating a history of COVID-19 infection among family members and friends.

3.2. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine

Overall, 69% (1374/2006) of participants were classified as willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine (48% were definitely willing and 21% were probably willing), and 31% (632/2006) were classified as not willing (17% were not sure, 5% were probably not willing, and 9% were definitely not willing). The most that participants indicated they would pay out-of-pocket for a COVID-19 vaccine was $0 (30%), $1-$19 (15%), $20-$49 (20%), $50-$99 (14%), $100-$199 (10%), and $200+ (11%). Several variables were correlated with willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in bivariate analyses (Table 2, Table 3 ).

Table 2.

Bivariate correlates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability for categorical variables.

| No. willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine / total no. in category (%) | Bivariate RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 651/868 (75) | ref. |

| Female | 714/1122 (64) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90)** |

| Other | 9/16 (56) | 0.75 (0.49–1.16) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 222/313 (71) | 0.93 (0.86–1.02) |

| 30–49 | 429/657 (65) | 0.86 (0.80–0.93)** |

| 50–64 | 340/532 (64) | 0.84 (0.78–0.91)** |

| 65 and older | 383/504 (76) | ref. |

| Race / ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Latinx | 941/1347 (70) | ref. |

| Black, non-Latinx | 133/240 (55) | 0.79 (0.70–0.89)** |

| Other race, non-Latinx | 122/178 (69) | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) |

| Latinx | 178/241 (74) | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 347/532 (65) | ref. |

| Married/civil union or living with partner | 715/1016 (70) | 1.08 (1.00–1.16)* |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 312/458 (68) | 1.04 (0.96–1.14) |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school degree | 54/105 (51) | ref. |

| High school degree | 364/589 (62) | 1.20 (0.99–1.46) |

| Some college | 412/629 (66) | 1.27 (1.05–1.55)** |

| College degree or more | 544/683 (80) | 1.55 (1.28–1.87)** |

| Household income | ||

| Less than $50,000 | 654/1058 (62) | ref. |

| $50,000 to $89,999 | 387/527 (73) | 1.18 (1.11–1.27)** |

| $90,000 or more | 333/421 (79) | 1.28 (1.20–1.37)** |

| Political leaning | ||

| Conservative | 387/653 (59) | ref. |

| Moderate | 592/850 (70) | 1.17 (1.09–1.27)** |

| Liberal | 395/503 (79) | 1.33 (1.23–1.43)** |

| Religiosity | ||

| Not at all or slightly important | 505/715 (71) | ref. |

| Fairly, very, or extremely important | 869/1291 (67) | 0.95 (0.90–1.01)† |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Straight | 1251/1837 (68) | ref. |

| Other | 123/169 (73) | 1.07 (0.97–1.18)† |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Rural | 171/276 (62) | ref. |

| Urban | 1200/1722 (70) | 1.13 (1.02–1.24)* |

| Region of residence | ||

| Northeast | 297/380 (78) | ref. |

| North Central | 280/441 (64) | 0.81 (0.74–0.89)** |

| South | 501/767 (65) | 0.84 (0.78–0.90)** |

| West | 296/418 (71) | 0.91 (0.84–0.98)* |

| Health-Related Characteristics | ||

| Health insurance | ||

| None | 124/246 (50) | ref. |

| Private insurance | 619/830 (75) | 1.48 (1.30–1.69)** |

| Public insurance | 631/930 (68) | 1.35 (1.18–1.54)** |

| Underlying medical condition | ||

| No | 849/1285 (66) | ref. |

| Yes | 525/721 (73) | 1.10 (1.04–1.17)** |

| Ever tested for COVID-19 | ||

| No | 1184/1771 (67) | ref. |

| Yes | 190/235 (81) | 1.21 (1.13–1.30)** |

| Personal history of COVID-19 diagnosis | ||

| No | 1311/1932 (68) | ref. |

| Yes | 63/74 (85) | 1.26 (1.14–1.39)** |

| Family member/friend ever diagnosed with COVID-19 | ||

| No | 1159/1712 (68) | ref. |

| Yes | 215/294 (73) | 1.08 (1.00–1.17)* |

| Think healthcare provider would recommend COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| No | 98/327 (30) | ref. |

| Yes | 1276/1679 (76) | 2.54 (2.14–3.00)** |

Note. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval; ref = reference group.

p < 0.20;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

Table 3.

Bivariate correlates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability for continuous variables.

| Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Willing | Willing | Bivariate RR (95% CI) | |

| (n = 632) |

(n = 1374) |

||

| Knowledge about COVID-19 infectiona | 0.71 (0.23) | 0.76 (0.18) | 1.54 (1.31–1.82)** |

| Perceived likelihood of COVID-19 infection in the futureb | 2.20 (0.78) | 2.53 (0.73) | 1.19 (1.15–1.24)** |

| Perceived severity of COVID-19 infectionc | 2.72 (1.04) | 3.22 (0.82) | 1.21 (1.17–1.26)** |

| Perceived stigma of COVID-19 infectiond | 2.47 (0.92) | 2.44 (0.97) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

| Perceived effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccinee | 2.24 (0.86) | 3.25 (0.66) | 1.62 (1.56–1.68)** |

| Perceived potential harms of a COVID-19 vaccinef | 3.87 (0.97) | 3.73 (0.83) | 0.94 (0.91–0.98)* |

| Perceived unavailability of a COVID-19 vaccinef | 2.61 (1.05) | 2.65 (1.25) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) |

| Self-efficacy to engage in protective behaviors against COVID-19f | 4.24 (0.87) | 4.39 (0.75) | 1.08 (1.03–1.13)** |

| Perceived positive social norms of protective behaviors against COVID-19 in communityf | 3.67 (1.05) | 3.93 (1.01) | 1.08 (1.05–1.12)** |

Note. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

Proportion of five knowledge items answered correctly (possible range = 0–1).

1 item; 4-point response scale ranging from “no chance” to “high chance” (possible range = 1–4).

1 item; 4-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “very” (possible range = 1–4).

4 item scale; each item had a 5-point response scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (possible range = 1–5).

1 item; 4-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot” (possible range = 1–4).

1 item; 5-point response scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (possible range = 1–5).

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001; †p < 0.20;

In multivariable analyses (Table 4 ), participants were more likely to be willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine if they had an income of $50,000-$89,999 (RR = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.01–1.14) or $90,000 or more (RR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.16), were moderate (RR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.16) or liberal (RR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.07–1.22) in their political leaning, had private health insurance (RR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.00–1.26), reported a personal history of COVID-19 infection (RR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.01–1.27), or thought their healthcare provider would recommend they get vaccinated (RR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.49–2.02). Participants were also more likely to be willing if they reported higher levels of perceived likelihood of getting a COVID-19 infection in the future (RR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.01–1.09), perceived severity of COVID-19 infection (RR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.04–1.11), or perceived effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine (RR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.40–1.52). Participants were less likely to be willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine if they were female (RR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.87–0.96), non-Latinx black (RR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.74–0.90), or reported a higher level of perceived potential harms of a COVID-19 vaccine (RR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92–0.98).

Table 4.

Multivariable correlates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptability.

| Multivariable RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Gender | |

| Male | ref. |

| Female | 0.91 (0.87–0.96)** |

| Other | 0.78 (0.53–1.17) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–29 | 1.04 (0.94–1.15) |

| 30–49 | 0.93 (0.85–1.00) |

| 50–64 | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) |

| 65 and older | ref. |

| Race / ethnicity | |

| White, non-Latinx | ref. |

| Black, non-Latinx | 0.81 (0.74–0.90)** |

| Other race, non-Latinx | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) |

| Latinx | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) |

| Household income | |

| Less than $50,000 | ref. |

| $50,000 to $89,999 | 1.07 (1.01–1.14)* |

| $90,000 or more | 1.09 (1.02–1.16)* |

| Political leaning | |

| Conservative | ref. |

| Moderate | 1.09 (1.02–1.16)* |

| Liberal | 1.14 (1.07–1.22)** |

| Health-Related Characteristics | |

| Health insurance | |

| None | ref. |

| Private insurance | 1.12 (1.00–1.26)* |

| Public insurance | 1.06 (0.94–1.20) |

| Personal history of COVID-19 diagnosis | |

| No | ref. |

| Yes | 1.13 (1.01–1.27)* |

| Think healthcare provider would recommend COVID-19 vaccine | |

| No | ref. |

| Yes | 1.73 (1.49–2.02)** |

| Attitudes and Beliefs | |

| Knowledge about COVID-19 infectiona | 1.16 (1.00–1.36) |

| Perceived likelihood of getting COVID-19 infection in the futureb | 1.05 (1.01–1.09)* |

| Perceived severity of COVID-19 infectionc | 1.08 (1.04–1.11)** |

| Perceived effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccined | 1.46 (1.40–1.52)** |

| Perceived potential harms of a COVID-19 vaccinee | 0.95 (0.92–0.98)* |

Note. Final multivariable model included only those variables presented in this table. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; RR = relative risk; CI = confidence interval; ref = reference group.

Proportion of five knowledge items answered correctly (possible range = 0–1).

1 item; 4-point response scale ranging from “no chance” to “high chance” (possible range = 1–4).

1 item; 4-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “very” (possible range = 1–4).

1 item; 4-point response scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot” (possible range = 1–4).

1 item; 5-point response scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (possible range = 1–5).

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001

3.3. Factors in vaccination decisions

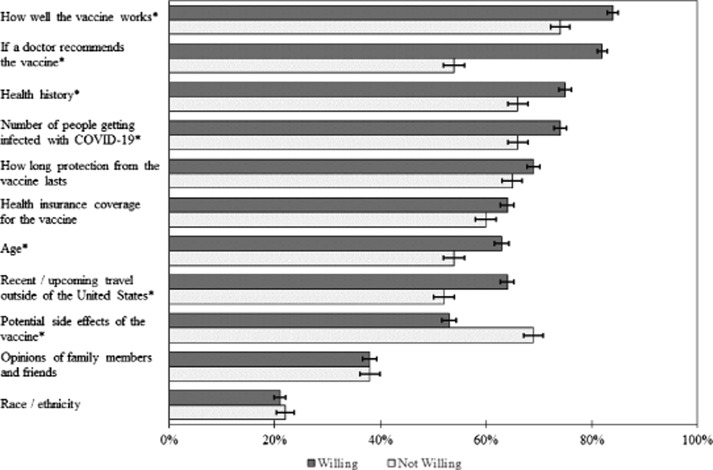

A majority of participants indicated that the following factors would matter in their vaccination decisions: how well the vaccine works (81%), if a doctor recommends the vaccine (73%), their health history (e.g., presence of an underlying medical condition) (72%), the number of people getting infected with COVID-19 (72%), how long protection from the vaccine lasts (68%), health insurance coverage for the vaccine (62%), their age (60%), recent or upcoming travel outside of the US (60%), and potential side effects of the vaccine (58%). Fewer participants indicated that the opinions of their family members and friends (38%) and their race/ethnicity (21%) would matter in their vaccination decisions.

Participants who were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine were more likely to indicate the following factors as mattering in their vaccination decisions compared to those who were not willing (all p < 0.05; Fig. 1 ): how well the vaccine works (84% vs. 74%), if a doctor recommends the vaccine (82% vs. 54%), their health history (75% vs. 66%), the number of people getting infected with COVID-19 (74% vs. 66%), their age (63% vs. 54%), and recent or upcoming travel outside of the US (64% vs. 52%). Conversely, participants who were willing to get vaccinated were less likely to indicate potential vaccine side effects as mattering in their vaccination decisions (53% vs. 69%, p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Factors that would matter in participants’ decisions about COVID-19 vaccination by vaccine willingness. Bars indicate standard errors. ‘*’ indicates a comparison with p < 0.05, based on chi-square tests with the Bonferroni adjustment to account for multiple testing.

4. Discussion

We found that nearly 70% of adults in the US would be willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine if one becomes available. This is similar to data recently made available online, where 59%-75% of US adults indicated a willingness to get vaccinated [18], [19]. Our finding represents one of the first estimates of acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine in the US and can be used to guide projections of future vaccine uptake. Moving forward, it will be important to monitor temporal changes in acceptability as vaccine development continues, and, if a vaccine becomes available, determine how estimates of acceptability translate into vaccine uptake since willingness/intent may not always lead to actual behavior.

Vaccine acceptability was lower among several demographic groups, including participants who were non-Latinx black, had lower incomes, had no health insurance, or were conservative in their political leaning. The pattern among non-Latinx black participants is concerning since early data suggest that non-Latinx blacks have among the highest COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates in the US [20], [21], [22]. It is, however, encouraging that vaccine acceptability was high among Latinx participants, as the Latinx population has also experienced a high burden of COVID-19 [20], [21], [22]. If a vaccine becomes available, ensuring vaccine uptake among these populations may help lessen these existing disparities related to COVID-19. Our findings for income and health insurance coincide with past research, which found uptake of other vaccines was lower among individuals with lower socioeconomic status or without health insurance [23]. Several states have already indicated that they will require insurers to cover COVID-19 vaccination with no cost-sharing following vaccine availability [24], which may help facilitate vaccine uptake by reducing potential financial barriers. Reducing such barriers is important since only 35% of participants in our study would pay $50 or more out-of-pocket for a COVID-19 vaccine. The finding concerning political leaning may reflect the polarization of issues related to COVID-19 by political leaning. Indeed, individuals with a conservative political leaning may perceive lower risk of COVID-19 infection and may be less likely to engage in protective behaviors (e.g., social distancing, wearing a mask) [25].

One of the strongest correlates of vaccine acceptability was whether participants thought their healthcare provider would recommend they get vaccinated against COVID-19. Provider recommendation is a key determinant of vaccination behaviors [26] though missed opportunities for healthcare providers recommending and administering vaccines to patients are still common [27]. If a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, strong healthcare provider recommendations will be critical to promoting vaccine uptake among vaccine-eligible patients. Several health beliefs were also correlated with vaccine acceptability (i.e., perceived likelihood, perceived severity, perceived vaccine effectiveness, perceived potential vaccine harms). These beliefs are central constructs of multiple health behavior theories (e.g., Health Belief Model [28], Protection Motivation Theory [29] and have been correlated with the acceptability and uptake of other vaccines [30], [31]. Importantly, these beliefs also represent modifiable targets for future interventions. Past interventions that have included components targeting such beliefs have been successful in improving knowledge, attitudes/beliefs, and uptake of other vaccines [32], [33], [34].

The results of our survey activity where participants indicated the factors that would matter in their vaccination decisions lend support to the findings from our regression analyses. For example, many of the most commonly endorsed factors (e.g., those related to vaccine effectiveness, healthcare provider recommendation, cost/insurance coverage, and vaccine side effects) are similar to constructs identified as correlates of vaccine acceptability. Results of this survey activity also highlight that the importance of certain factors may differ depending on how ready a person is to get vaccinated, and we think this has implications for future communication efforts about a COVID-19 vaccine. For example, communications for people who are more ready to get vaccinated (i.e., those classified as willing in our study) may need to focus more on issues like vaccine efficacy and healthcare provider recommendation, whereas communications for people who are less ready to get vaccinated (i.e., those classified as not willing in our study) may need to focus more on reducing concern about vaccine side effects. This approach would coincide well with several of the stage theories in health behavior (e.g., Transtheoretical Model [35] and Precaution Adoption Process Model [36], in which the resources and information needed often vary depending on a person’s stage of behavior change.

The strengths of our study include a large sample size, participants from throughout the entire US, and examining a wide range of possible correlates. A key limitation of this study is that we recruited a convenience sample of participants from an opt-in survey panel. Although the demographic characteristics of our participants are similar to those of the US population [37], this limitation should be considered in interpreting and applying the results of the current study. Additional limitations include the study’s cross-sectional design and lack of available data on non-respondents. Given that data collection occurred during the early stages of development of a COVID-19 vaccine, we were not able to provide participants with information about details that could affect vaccine acceptability (e.g., dosing schedule). Lastly, our survey assessed vaccine acceptability under the condition that the vaccine was free or covered by health insurance, and acceptability might be lower if there would be out-of-pocket costs associated with the vaccine.

5. Conclusions

If a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, it will be a key public health strategy for reducing existing disparities and the overall disease burden due to COVID-19. Our study provides early insight into the acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine, with results indicating that many adults in the US would be willing to get vaccinated if a vaccine becomes available. As the vaccine development process continues, it will be important to monitor changes in people’s vaccine acceptability. Our results highlight that vaccine acceptability may differ by several demographic characteristics, as well as the key role that healthcare providers and modifiable health beliefs play in acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine. These findings can help guide the planning and development of future public health efforts to increase acceptability (and uptake following vaccine licensure) of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Funding

Supported by Award Number Grant UL1TR002733 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Zhou M., Zhang X., Qu J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A clinical update. Front Med. 2020;14(2):126–135. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0767-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bish A., Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 4):797–824. doi: 10.1348/135910710X485826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thanh Le T., Andreadakis Z., Kumar A. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):305–306. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharpe HR, Gilbride C, Allen E, et al. The early landscape of COVID-19 vaccine development in the UK and rest of the world. Immunology. (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Lanese N. When will a COVID-19 vaccine be ready? 2020. Available at: https://www.livescience.com/coronavirus-covid-19-vaccine-timeline.html.

- 7.Gidengil C.A., Parker A.M., Zikmund-Fisher B.J. Trends in risk perceptions and vaccination intentions: A longitudinal study of the first year of the H1N1 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(4):672–679. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurer J., Harris K.M., Parker A., Lurie N. Does receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine predict intention to receive novel H1N1 vaccine: Evidence from a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults. Vaccine. 2009;27(42):5732–5734. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horney J.A., Moore Z., Davis M., MacDonald P.D. Intent to receive pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccine, compliance with social distancing and sources of information in NC, 2009. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reiter P.L., McRee A.L., Gottlieb S.L., Markowitz L.E., Brewer N.T. Uptake of 2009 H1N1 vaccine among adolescent females. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(2):191–196. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.2.13847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McRee A.L., Brewer N.T., Reiter P.L., Gottlieb S.L., Smith J.S. The carolina HPV immunization attitudes and beliefs scale (CHIAS): Scale development and associations with intentions to vaccinate. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(4):234–239. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c37e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiter P.L., McRee A.L., Gottlieb S.L., Brewer N.T. Correlates of receiving recommended adolescent vaccines among adolescent females in North Carolina. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(1):67–73. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.1.13500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiter P.L., McRee A.L., Pepper J.K., Gilkey M.B., Galbraith K.V., Brewer N.T. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1419–1427. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiter P.L., McRee A.L., Katz M.L., Paskett E.D. Human papillomavirus vaccination among young adult gay and bisexual men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):96–102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural-Urban Continuum codes. 2016. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes//.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): People who are at higher risk for severe illness. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html. [PubMed]

- 17.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.JCH Impact. New Yorkers and COVID-19 (week 7). 2020. Available at: https://jhcimpact.com/posts/f/new-yorkers-and-covid-19-week-7.

- 19.Kelly B, Bann C, Squiers L, Lynch M, Southwell B, McCormack L. Predicting willingness to vaccinate for COVID-19 in the US. 2020. Available at: https://jhcimpact.com/posts/f/predicting-willingness-to-vaccinate-for-covid-19-in-the-us.

- 20.Webb Hooper M, Napoles AM, Perez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. (In press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.APM Research Lab. The color of coronavirus: COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity in the U.S. 2020. Available at: https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race.

- 22.Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang S, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population level COVID-19 mortality. 2020. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.07.20094250v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Pazol K., Robbins C.L., Black L.I. Receipt of selected preventive health services for women and men of reproductive age - United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(20):1–31. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6620a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser Family Foundation. State data and policy actions to address coronavirus. 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/.

- 25.Van Bavel JJ. In a pandemic, political polarization could kill people. 2020. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/03/23/coronavirus-polarization-political-exaggeration/.

- 26.Rodriguez S.A., Mullen P.D., Lopez D.M., Savas L.S., Fernandez M.E. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the U.S.: A systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev Med. 2020;131:105968. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aris E., Montourcy M., Esterberg E., Kurosky S.K., Poston S., Hogea C. The adult vaccination landscape in the United States during the Affordable Care Act era: Results from a large retrospective database analysis. Vaccine. 2020;38(14):2984–2994. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker M.H. The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324–473. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers R.W. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In: Cacioppo J.T., Petty R.E., editors. Social psychophysiology: A source book. Guilford Press; New York: 1983. pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reiter P.L., Brewer N.T., Gottlieb S.L., McRee A.L., Smith J.S. Parents’ health beliefs and HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(3):475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling M., Kothe E.J., Mullan B.A. Predicting intention to receive a seasonal influenza vaccination using protection motivation theory. Soc Sci Med. 2019;233:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gargano L.M., Herbert N.L., Painter J.E. Development, theoretical framework, and evaluation of a parent and teacher-delivered intervention on adolescent vaccination. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(4):556–567. doi: 10.1177/1524839913518222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McRee A.L., Shoben A., Bauermeister J.A., Katz M.L., Paskett E.D., Reiter P.L. Outsmart HPV: Acceptability and short-term effects of a web-based HPV vaccination intervention for young adult gay and bisexual men. Vaccine. 2018;36(52):8158–8164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reiter P.L., Katz M.L., Bauermeister J.A., Shoben A.B., Paskett E.D., McRee A.L. Increasing human papillomavirus vaccination among young gay and bisexual men: A randomized pilot trial of the Outsmart HPV intervention. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):325–329. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prochaska J.O., DiClemente C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinstein N.D., Sandman P.M. A model of the precaution adoption process: Evidence from home radon testing. Health Psychol. 1992;11(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United States Census Bureau. American community survey (ACS). 2020. Available at: http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.