Abstract

Musical experiences are ubiquitous in early childhood. Beyond potential benefits of musical activities for young children with typical development, there has long been interest in harnessing music for therapeutic purposes for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, there is debate as to the effectiveness of these approaches and thus a need to identify mechanisms of change (or active ingredients) by which musical experiences may impact social development in young children with ASD. In this review, we introduce the PRESS-Play framework, which conceptualizes musical activities for young children with ASD within an applied behavior analysis framework consistent with the principles of naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions. Specifically, the PRESS-Play framework proposes that musical activities support key elements of evidence-based approaches for social engagement including predictability, reinforcement, emotion regulation, shared attention, and social play context, providing a platform for delivery and receipt of social and behavioral instruction via a transactional, developmental approach. PRESS-Play considers that these factors may impact not only the child with ASD but also their interaction partner, such as a parent or peer, creating contexts conducive for validated social engagement and interaction. These principles point to focused theories of change within a clinical-translational framework in order to experimentally test components of social-musical engagement and conduct rigorous, evidence-based intervention studies.

Introduction

Social musical experiences are both natural and ubiquitous in early childhood interactions between parents and their children, and children and their peers (Politimou et al., 2018; Trainor & Cirelli, 2015; Trehub & Cirelli, 2018). Beginning in infancy, singing and musical play capture and maintain children’s attention, modulate their arousal levels, and provide redundant and highly salient cues (Cirelli et al., 2019; Nakata & Trehub, 2004; Trehub et al., 2016). In addition, children use child-directed singing as a meaningful marker of social attention and affiliation, showing increased attention to, social preference for, and prosocial behavior toward people who sing songs from their parents’ repertoire (Cirelli, Trehub, et al., 2018; Cirelli & Trehub, 2018; Mehr et al., 2016). Shared musical activities that promote synchronous movement between children and their peers or adults support prosocial behaviors such as helping and cooperation (Cirelli et al., 2014; Kirschner & Tomasello, 2009). Behavior analysis of music engagement during early typical development suggests that musical interaction directly and incidentally scaffolds children’s social engagement with their parents and their peers.

Beyond potential social benefits of music for typically developing (TD) children and families, there has long been substantial interest in harnessing music for therapeutic goals in children with disabilities (see Alley, 1979) including autism spectrum disorder (ASD; see Alvin & Warwick, 1978). ASD is a common (1 in 59 children) and lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in social communication and interaction as well as restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Baio et al., 2018). The earliest reports on ASD suggested interest in and propensity for music (Kanner, 1943). Subsequent behavioral studies generally reflected relatively preserved skills in areas such as pitch perception (e.g., Heaton, 2003) and musical emotion recognition (e.g., Quintin, Bhatara, Poissant, Fombonne, & Levitin, 2011). More recent neuroimaging studies reported typical neural processing of musical or sung stimuli in children with ASD (Caria et al., 2011; Sharda et al., 2015). Some children with ASD have selective preferences for musical activities (e.g., listening to music, playing an instrument) and will repeatedly engage in and gain proficiency with musical activities (Bennett & Heaton, 2012; Happe & Frith, 2010; Kanner, 1943).

Music perception and production engages multiple areas and networks of the brain involving sensory, motor, emotional, attentional, and social processes leading to hypotheses that musical experiences may transfer to non-musical skills due to shared neural resources (e.g., Patel, 2011; Wan & Schlaug, 2010). These hypotheses have been applied to music therapy approaches for children with ASD, particularly through the lens of musical experiences impacting neural pathways involved in attention, sensory, motor, and emotional processes that support social communication (Janzen & Thaut, 2018; Overy & Molnar-Szakacs, 2009; Sharda et al., 2018; Trevarthen, 2002; Wan et al., 2011; see Janzen & Thaut (2018), Geretsegger et al. (2014) or Srinivasan & Bhat (2013) for reviews of music therapy approaches and findings). There are credible, albeit limited, studies supporting musical engagement for non-musical social and communicative goals for children with ASD, including those drawn from music therapy (Geretsegger et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2008; Sharda et al., 2018) and music education (Cook et al., 2018; Kern et al., 2007; McFerran et al., 2016) literatures. At the same time, a large-scale improvisational music therapy trial did not yield effects on autism symptoms relative to a non-music treatment (e.g., Bieleninik et al., 2017; though note concerns with intervention fidelity and outcome measures) and debates continue over the effectiveness of specific therapeutic approaches (Accordino et al., 2007; Sharda et al., 2019; Sreewichian, 2019). There is an urgent need to objectively identify the core components (also termed active ingredients) of interventions for children with ASD (Pellecchia et al., 2015). Identifying the active ingredients that underlie the mechanisms of change by which musical experiences may impact social engagement will help to refine and advance musical interventions for young children with ASD (Cheever et al., 2018; Collins & Fleming, 2017).

The long standing focus in behavioral treatments for young children with ASD is expanding from analog, clinician implemented techniques to include parent-implemented interventions and naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions (NDBIs) that incorporate behavior analytic principles and the developmental context of skill development (e.g., Pivotal Response Treatment (Koegel et al., 2016); see Schreibman et al., 2015 for a review). Such approaches teach parents skills to support their interactions with their children during natural play interactions and daily routines, providing a scaffolding therapeutic context for the development of foundational social skills. In the current paper, we introduce the PRESS-Play framework, which draws upon behavioral and neuroscientific principles to consider musical engagement as a potential NDBI platform for delivering social and communicative teaching events that align with key ingredients validated in multiple studies of NDBIs for young children with ASD (e.g., Pivotal Response Treatment (Koegel et al., 2016), Symbolic play (Kasari et al., 2006), Reciprocal Imitation Training (Ingersoll & Schreibman, 2009)). PRESS-Play explicitly and uniquely integrates musical experiences with NDBI principles to consider how musical engagement may provide a direct or indirect, effective, scaffolding therapeutic context for supporting social development while also building and enhancing parents’ therapeutic skills by supporting highly effective teaching events to their children.

In the PRESS-Play framework, we propose that the essential elements of musical engagement experiences that align with evidence-based NDBI approaches for social engagement skill development in young children with ASD include: (1) Predictability; (2) Reinforcement; (3) Emotion Regulation; (4) Shared Attention; and (5) Social Play context. These components (which are not discrete but interact with each other and are not unique to music, but, in fact, are key components and active ingredients in diverse treatments for ASD) apply not only to a child with ASD but also their interaction partners (such as a parent or peer). Musical experiences may create a context that helps a partner provide incidental transactional opportunities for, and be receptive to, moments of validated social engagement and interaction with young children (see Camarata & Yoder, 2002). From an NDBI perspective, incidental refers to naturally occurring opportunities that arise due to the affordances of the activities in which the child is motivated to participate while transactional highlights the interaction between the child and their social partner. Note that in this framework, music is not viewed as an isolated procedure nor, as a necessarily unique “primary” active ingredient for intervention, rather, it is viewed as a naturalistic readily applicable (and teachable) NDBI platform to deliver social and behavioral instruction to children with ASD. In the sections below, we outline the elements of PRESS-Play for supporting social engagement in typical development and implications for young children with ASD. We then discuss potential caveats or limitations to be considered, as well as suggest areas of future study. While passive musical listening may also play a role in facilitating specific activities, the focus of the current framework is active musical engagement experiences as part of a natural developmental context and which may be incorporated into and empirically tested as part of specific therapeutic programs.

The PRESS-Play Framework:

Social Play:

Musical play is a natural and ecologically valid play context for parents and children across developmental ability levels and disability typologies. Musical play occurs in all cultures starting with parents’ use of infant-directed singing from early infancy, building up to dyadic, triadic, and group musical play games of early childhood (Custodero, 2006; Ilari et al., 2011; Politimou et al., 2018; Trehub & Cirelli, 2018; Trevarthen, 1999). As musical activities are widely employed, natural, interactive, and child-directed, they may serve as an intervention context congruent with NDBIs. Contexts that are natural, motivating, and easily learned may assist the child with ASD and also their interaction partner (such as a parent or peer) in the seamless delivery of strategies that provide opportunities and natural reinforcers for the goal of social engagement.

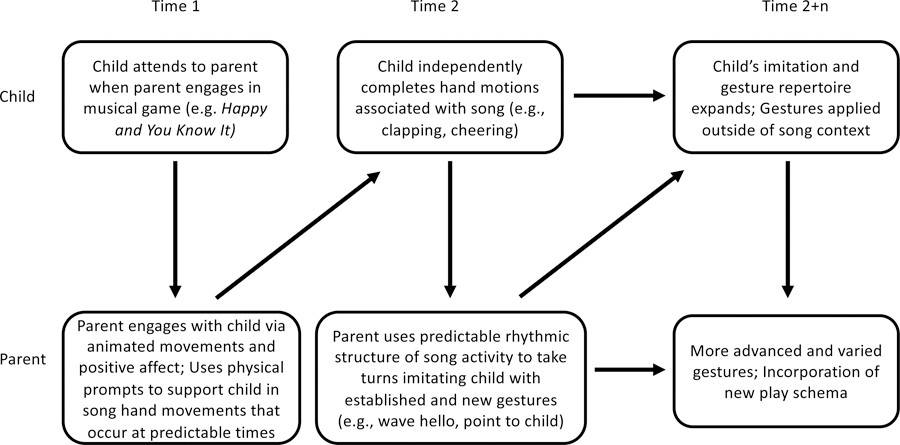

Like other forms of play (e.g., symbolic play, see Kasari, Gulsrud, Freeman, Paparella, & Hellemann, 2012), musical play activities involve social attention, language, symbolic play, and motor activities, providing opportunities to target goals across multiple domains simultaneously within a naturalistic, shared, transactional context. The play activities can be readily adapted to focus on different skills within a given repertoire or adjusted to different developmental levels for a child with ASD. For example, an initial focus might be to use animated singing and movement activities to capture a child’s attention, later to engage in imitation of hand movements that accompany a song, and later to incorporate pretend play when acting out the song; whichever context is engaging, motivating, and developmentally appropriate for a child with ASD (see Figure 1). The naturally exaggerated interaction style of rhythmic facial expressions and movements used during child-directed singing corresponds to techniques of being animated and expressive when engaged in therapy with children with ASD and may incidentally render these important social and linguistic cues more salient and teachable than in other social contexts.

Figure 1.

An example of the use of social musical interactions to support a child’s development of gestures and imitation. Arrows depict the transactional relationship between the child and parent in advancing the activity and associated skills over time.

Musical activities also provide a highly familiar and routinized play context with clear expectations and predictable routines. For example, a nursery rhyme like “Happy and You Know It” follows the same general structure whether it is sung by a parent, teacher, therapist, or peer, and includes music, vocabulary, gestures and social engagement in a predictable, repeated and, for many children, motivating and engaging platform. This, in turn, may provide a transferrable naturally occurring context for a child with ASD to generalize skills to different interaction partners or settings, which may be helped because the interaction partner knows what is expected of them, as well. The use of regular and consistent behavioral and linguistic strategies has long been known to support skill generalization across settings and communication partners for children with ASD (Kaiser et al., 2000; Reisinger, 1978). Thus, musical activities may incidentally provide a context that naturally delivers previously-identified evidence-based strategies often used when targeting social engagement and language development.

Predictability:

Musical routines involve predictable and salient rhythm and timing patterns. Beginning in infancy, parents’ use of rhythmic infant-directed speech and song attracts and maintains their child’s attention and creates engaging and motivating patterns in gaze and in vocalizations (Cirelli, Trehub, et al., 2018; Nakata & Trehub, 2004; Trehub & Gudmundsdottir, 2015). Social musical play heightens the structure and predictability of these social rhythms, i.e., the rhythmic coordination of communicative vocalizations, gaze, facial expressions, movements, and touch of parent-infant communication. This is particularly evident in the rhythms that structure how music unfolds over time such as the regular beat of many children’s songs, which is coordinated with the lyrics (though note the rhythmic signal need not be strictly isochronous). Dynamic Attending Theory (DAT) proposes that attention entrains to predictable, temporally organized signals such as music and speech, leading to the development of expectancies for when events will occur and facilitating processing of events at expected times (Large & Jones, 1999). Empirical investigations of DAT suggest that entrainment occurs cross-modally – auditory rhythms facilitate detection of auditory events (e.g., durational changes (McAuley & Fromboluti, 2014)), linguistic events (e.g., syllable detection or grammaticality judgments (Cason & Schön, 2012; Chern et al., 2018; Morrill et al., 2014), as well as visual events that occur at rhythmically expected times (Bolger et al., 2013; Escoffier et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2013). Entrainment is substantiated at the neural level via synchronized oscillatory activity that time-locks to rhythmic stimuli and is modulated by attention and experience (Escoffier et al., 2015; Fujioka et al., 2015; Iversen et al., 2009).

Attentional entrainment supported by the predictability of interactive musical activities thus has elements that directly and indirectly support social engagement and communication development in typical and atypical populations. The predictability provided by the rhythmic structure of musical activities may modulate attention to scaffold the timing of attention to important social events and draw attention to multiple linguistic elements embedded in the songs. For example, typically developing infants and toddlers modulate their gaze to the eyes of a singer when observing infant-directed singing based on the rhythmic structure (Lense & Jones, 2016).

An array of disruptions in attention are reported in children with ASD including impairments in attention attainment, disengagement, restricted attention on atypical environmental elements, and reduced initiation of and response to joint attention, which involves using or following cues to share attention with another person and relate to social and language development (Jones et al., 2017; Mansour et al., 2017) so that directly and/or indirectly supporting attention is likely to be a useful ingredient in intervention. Similarly, many individuals with ASD exhibit rhythmic timing difficulties in nonmusical contexts, particularly attending to socially-embedded activities such as coordination of vocal turn-taking, prosodic stress patterns, and synchrony of speech and gestures (Marchena & Eigsti, 2010; Paul et al., 2005; Ramsay, 2015; Shriberg et al., 2001). Although studies of rhythm skills in individuals with ASD are limited, a growing body of work has focused on the incidental benefits of the rhythmic elements of music for interventions in this population (e.g., Srinivasan, Eigsti, Gifford, & Bhat, 2016; Srinivasan et al., 2015; Yoo & Kim, 2018). A rhythmically predictable signal that structures a musical interaction may help both partners in an interaction time the delivery and receipt of meaningful information while providing important redundancy in social and linguistic contexts and cues (i.e., co-occurrence of multiple cues providing the same information). Indeed, increased eye contact and turn-taking have been observed during therapeutic musical activities vs. non-musical play in children with ASD (Kim et al., 2008; LaGasse, 2015; Srinivasan et al., 2016) and limited studies have reported improvements in joint attention following participation in music therapy (Kim et al., 2008; Srinivasan et al., 2016), which could be direct or indirect byproducts of the inherent predictability and salience of musical activities.

Musical activities also support sensory-motor integration due to the tight coupling of, for example, auditory and motor activity (Zimmerman & Lahav, 2012). Musical beat and rhythm perception are reliant on auditory-motor pathways and support entrainment and coordination of motor activity with systematic and predictable auditory and visual routines (Grahn et al., 2011; Grahn & McAuley, 2009). Music training has long been studied as an example of multisensory auditory-motor neuroplasticity in TD individuals (Hyde et al., 2009), but musical activities have only recently been examined in individuals with ASD in the context of exploring the role of simultaneous (and integrated) auditory-motor coordination for learning. For example, Auditory-Motor Mapping Training, which is based on Melodic Intonation Therapy previously developed for stroke patients (Schlaug et al., 2009), employs the explicit practice of linking motor movements (tapping on tuned drums) with sung (or intoned) speech to improve speech production in children with ASD (Chenausky et al., 2016, 2017; Wan et al., 2011). By tapping on the drums for each syllable produced, the training uses predictable musical routines to practice multisensory, auditory-motor skills important for speech development. In preliminary investigations, school-aged children participating in Auditory-Motor Mapping Training increased consonant and vowel speech production skills versus children in a control Speech Repetition therapy (Chenausky et al., 2016; Chenausky et al., 2017). In a separate, randomized controlled trial, school-aged children with autism participated in music therapy sessions that used music (musical instruments, songs, and rhythmic cues) to target communication, turn-taking, sensorimotor integration, and social appropriateness or a parallel non-music play therapy (Sharda et al., 2018). Children in the music therapy condition exhibited increased auditory-motor functional connectivity post-intervention compared to children in a parallel non-music play therapy (Sharda et al., 2018). Functional connectivity levels between multiple auditory and subcortical areas (thalamus, striatum) post-music therapy was associated with parent-reported communication skills (Sharda et al., 2018).

Improvements in intrapersonal movement coordination may also support increased interpersonal movement coordination. Musical activities may in part be a helpful therapeutic context because they provide a readily available (and ubiquitous) context with a clearer interaction signal (e.g., due to predictable overlearned song and movement routines and more inherently routinized timing of movement scaffolded by the predictable rhythms and repeated practice) for a partner to interpret and coordinate (see Shared Attention section below) and mirror. Familiar interpersonal movement coordination is naturally associated with affiliative and prosocial behaviors in TD adults and children. For example, TD infants and children are more likely to help others if they have moved synchronously (vs. asynchronously) with them during music and movement games (Cirelli et al., 2014; Kirschner & Tomasello, 2009). Although interpersonal movement coordination does not require music, musical activities provide a natural context for scaffolding the timing of movement acts and for engendering such coordinated interpersonal movement activity. As noted previously, music and related activities (e.g., nursery rhymes) often have a scaffolded movement coordination that can be overt (“heads and shoulders, knees and toes”) or incidental (“the wheels on the bus”).

Predictable rhythmic stimuli are also salient to infants and young children in part because they specify information cross-modally (Bahrick & Lickliter, 2004; Lewkowicz, 2003). For example, during child-directed singing, parents often use large visual facial expressions, movements and gestures, touch, and vestibular inputs (e.g., bouncing or rocking) all of which are temporally synchronized to the auditory rhythmic signal. These non-auditory rhythmic streams are also important for maintaining attention: TD infants attend longer to visual-only examples of singing vs. speech production (Trehub et al., 2013). Rhythmic entrainment not only modulates attention cross-modally (Bolger et al., 2013; Escoffier et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2013) but may also impact integration of cross-modal information (Su, 2014). Though speculative, given established difficulties with cross-modal integration in people with ASD (Stevenson et al., 2014), musical play may provide a context for supporting the modulation and integration of attention cross-modally in children with ASD.

Reinforcement and Emotion:

Social musical experiences are motivating and autoreinforcing for many individuals (Lim, 2010). Positive emotional experience that many individuals have with music may facilitate music’s reward value for learning social goals. For example, in a series of studies set in different sound environments, infants who were moved (by bouncing the infant up and down) synchronously with an adult demonstrated more prosocial helping behaviors toward the adult versus infants who were moved asynchronously (Cirelli et al., 2014, 2017). Infants exhibited greater spontaneous helping, as well as reduced fussiness, when the bouncing activity was accompanied by music rather than nonrhythmic nature sounds suggesting that music facilitated a more positive social experience (Cirelli et al., 2017). TD children demonstrate increases in smiles directed to peers during synchronous (vs. asynchronous) rhythm and movement games (Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2018).

Despite frequent disruptions in auditory sensitivities in individuals with ASD, music is reported to be a pleasant sensory experience, including as part of social interactions such as music and movement games with caregivers (Dickie, Baranek, Schultz, Watson, & McComish, 2009; Lense, 2018). For at least some individuals with ASD, musical games and materials may therefore be potent natural reinforcers (i.e., reinforcers that are inherent to the child’s goal) that can support learning, increasing motivation to engage in therapeutic activities and resulting in increased practice of skills (see Ferster, 2017). Increased frequency of social behaviors such as eye contact and turn-taking are reliably observed during therapeutic musical play in children with ASD (Kim et al., 2008; LaGasse, 2015). Increased participation and reciprocity may in turn be reinforcing for the play partner leading to synergistic increases in interaction behavior, which is consistent with NDBI principles (Chevallier et al., 2012). The use of music as a natural reinforcer can also be paired with using music as an extrinsic positive reinforcer (e.g., access to a preferred musical toy or video or song as a consequence for completing an unrelated behavioral task).

Emotional and arousal modulation by music are the primary reasons people engage with music (Juslin & Västfjäll, 2008). From infancy, parents’ singing is a potent mood regulator. Infants will remain calm longer during parental singing vs. speaking and maternal singing more effectively calms distressed infants than maternal speaking (Corbeil et al., 2016; Trehub et al., 2015). Singing to their infants also modulates parents’ arousal levels as indicated by physiological markers (cortisol, skin conductance) and self-report ratings (Cirelli et al., 2019; Fancourt & Perkins, 2018). Difficulties with emotion/arousal regulation are common in people with ASD (Mazefsky et al., 2013) and may relate to factors such as altered arousal levels (e.g., hyperarousal) (Patriquin et al., 2019), impairments in describing and identifying emotions (alexithymia) (Kinnaird et al., 2019), reduced use of adaptive coping strategies (Samson et al., 2015), and comorbid mental health problems such as anxiety (Conner et al., 2020; Mazefsky et al., 2013). However, physiological responses to emotional music appear to be similar in individuals with ASD and TD individuals (Allen et al., 2013) and individuals with ASD report using music for arousal regulation (Allen et al., 2009).

In addition to the positive emotional experiences of music providing reinforcement, musical activities may also facilitate opportunities for learning and social connection due to arousal/emotion modulation. Emotional regulation is important for learning and memory including in relation to social communication skills (Prizant et al., 2003). Arousal regulation also promotes social bonding and cooperation independently and in interaction with movement synchrony (Jackson et al., 2018). Such arousal impacts of music may be important not only for a child with ASD but also for their interaction partners. Parents of children with ASD experience higher parenting stress and physiological markers of stress dysregulation (Hayes & Watson, 2013; Seltzer et al., 2010). High stress levels may impact parents’ ability to learn and apply skills learned in parent-mediated therapies and there is increasing awareness of the need to support parents in interventions including outcomes related to parent-child dynamics, parenting stress, and quality of life (Strauss et al., 2012; Wainer et al., 2017). Thus, another mechanism by which musical activities may have a role in supporting social engagement is by regulating arousal in all interaction partners to facilitate opportunities to learn and apply specific therapeutic skills.

Shared Attention:

Reductions in the amount of, and reductions in the quality of the shared attention episodes that do occur, are a key trait in individuals with ASD (see Franchini, Armstrong, Schaer, & Smith, 2018). When music is a viable motivator-reinforcer, joint musical play is an opportunity for shared attention between interaction partners. As noted previously, therapeutic musical activities are associated with increased eye contact to play partners (peers, therapists) in children with ASD as compared to during non-music play (Kim et al., 2008; LaGasse, 2015). Increased attention to others may be associated with musical facilitation of joint movement activity. TD children have been found to make more eye contact with peers during a synchronous vs. non-synchronous rhythmic movement game (Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2018) and more eye contact with an adult during musical as compared to non-musical play (Beck & Rieser, 2017). During music and dancing activities, TD adults demonstrate increased attention to other adults moving synchronously versus asynchronously with them (Woolhouse et al., 2016).

Positive shared attention (between parent-child or peer partners) during music is a form of naturally occurring social engagement arising from joint attention and coordination that can be reinforcing in itself and the impact can be bidirectional across social partners. For example, parents smile more when singing as compared to speaking to their infants (Trehub et al., 2016). Positive parental attention through behaviors such as directed gaze, contingent utterances, and imitation is a focus of many parent-child therapeutic programs (e.g., Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011)) including for children with ASD (e.g., Project ImPACT (Ingersoll & Dvortcsak, 2010)) and such activities increase a child’s attention to their partner (Dawson & Adams, 1984). During NDBIs, parents are frequently taught to shadow children’s initiations in joint activities by following a child’s focus of attention, providing cues and contingent responses to reinforce and shape specific behaviors (e.g., Dawson & Adams, 1984; Ingersoll & Gergans, 2006). Given their familiarity and structure, shared musical activities can provide a platform for joint experiences that are accessible for interaction partners. For example, the rhythmically-aligned movement activity and iconic gestures that accompany many musical games provide opportunities for showing attention through simultaneous and reciprocal imitation.

Summary, Future Directions, and Caveats

The PRESS-Play framework offers a set of principles for the use of music to support social engagement in young children via a developmental framework that connects with current theories of therapeutic practice for children with ASD, particularly NDBIs. These elements are measurable and can be tested within the context of experimental and clinical trials. Musical activities may provide a context for targeting social engagement because they include components that may serve to support not only a child with ASD but also their interaction partner, increasing opportunities for joint engagement. Moreover, music is viewed herein as a platform for delivering know teaching responses to children with ASD.

We also argue that PRESS-Play suggests areas for further research in both assessment and intervention studies in order to experimentally test mechanisms of active musical experiences such as scaffolding parent-child engagement and joint attention. Despite the longstanding interest and widespread belief in the positive effects of music therapy, knowledge of music cognition broadly and social music cognition specifically in individuals with ASD is quite limited. For example, while the role of rhythm in modulating attention and coordinating motor activities is increasingly studied in both typical and patient populations (e.g., language delay (Cumming et al., 2015; Wiens & Gordon, 2018), dyslexia (Leong & Goswami, 2014), aphasia (Schlaug et al., 2010)), there are few studies of rhythm perception or production in children or adults with ASD at either a behavioral or neural level (see DePape, Hall, Tillmann, & Trainor, 2012 for example of meter perception in individuals with ASD). In comparison, there are multiple studies of pitch perception (e.g., Heaton, Hermelin, & Pring, 1998; Heaton, 2003, 2005). Given the core social difficulties in individuals with ASD, there is an ongoing need for examining these skills (e.g., rhythm perception; rhythmic auditory-motor coordination) in naturalistic settings to evaluate the ecological validity of these components to support social engagement. The interactions of these parameters (e.g., attention modulation and multisensory integration; arousal and movement coordination) as predictors of growth in children with ASD must also be considered. Difficulties with rhythm and timing co-occur with a range of developmental, medical, and mental health conditions (Peretz & Vuvan, 2017). Comparing the nature and extent of these difficulties across conditions and contexts may shed light into common and unique mechanisms by which rhythm skills interact with broad measurements of social engagement or specific social communication skills (e.g., timing of gestures, producing vocalizations/words).

From an intervention perspective, PRESS-Play highlights the need for specifying the developmental context of musical interactions, incorporating parents or peers into the therapeutic context, and considering the impact of the active ingredients on the parents or peers included in the interaction. This may be reflected in dyadic measurements such as interpersonal movement coordination as well as specific behaviors from both partners in the therapeutic experience (e.g., physiological arousal, eye contact, or imitation by the child and parent during parent-child interaction). Health outcomes unique to partners should also be considered such as parenting stress and quality of life for parents/families and attitudes toward inclusion practices or peer acceptance for peers. As with all interventions, in order to build an evidence base, careful consideration and unbiased testing must be given to specification of the active ingredients (i.e., core components) believed to be essential to the theory of change, the differential components of the specific treatments being compared (especially due to the ubiquity of musical activities for young children), measurement of treatment fidelity, and choice of outcome measures (specific skills vs. broad constructs), all of which is in accord with NDBI methodology.

Despite the long-standing considerable interest and enthusiasm for harnessing music for therapeutic purposes for social engagement in individuals with ASD, and the plethora of testimonials (e.g., Schwartzberg & Silverman, 2017; Thompson, 2017), there are also many caveats to be considered. For example, while the predictability of musical activities is hypothesized to support engagement by guiding attention and expectations, a focus on predictable rhythms could simultaneously support a preference for repetitive activities which could possibly reduce social engagement. The use of children’s musical toys (e.g., children’s percussion instruments) or other instruments likely needs to be monitored as they may support a focus on repetitive cause-and-effect activities and an overemphasis on instruments or routinized songs could preclude use of flexible speech (by the parent or child). Similarly, the potentially reinforcing nature of musical activities must be individually evaluated using strict behavioral criteria as musical activities may not be enjoyable and motivating for all children. Musical activities must not come at the expense of participating in an array of experiences and modalities. It is also possible that musical interactions primarily impact the interaction partner rather than the child with ASD and while PRESS-Play views this as a potential method of change via creating a context conducive to interactions, at this time the direction of effects or potential for interaction cascades is unknown. Particularly when considering the heterogeneity among individuals with ASD, clearly elucidated theories of change will help determine for whom such approaches may be most effective.

Conclusions

PRESS-Play proposes that social musical activities for young children align with the principles of NDBI approaches to supporting social engagement in children with ASD. Musical activities can create a transactional platform for scaffolding foundational social skills and providing direct and indirect opportunities for the delivery of social and linguistic information consistent with the active ingredients of NDBIs. Social musical interactions incorporate predictability, reinforcement, emotion modulation, and shared attention within an ecologically and developmentally appropriate social play framework. PRESS-Play highlights the need to consider the potential impact of musical experiences for all interaction partners (not just the child with ASD) and that potential mechanisms of action may arise from creating a context conducive to the delivery and receipt of meaningful social engagement for all involved parties. These principles suggest avenues for systematic research to identify the active ingredients of musical experiences and select appropriate intervention targets within a clinical-translational framework, in order to move forward our understanding and application of musical experiences consistent with evidence-based practices for children with ASD.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by awards from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (R21DC016710) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R61MH123029) of the National Institutes of Health, as well as the National Endowment for the Arts (1844332-38-C-18). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). This work was additionally supported by the Program for Music, Mind & Society at Vanderbilt (with funding from the Trans-Institutional Programs Initiative), the VUMC Faculty Research Scholars Program, and the VUMC Department of Otolaryngology.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

References

- Accordino R, Comer R, & Heller WB (2007). Searching for music’s potential: A critical examination of research on music therapy with individuals with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1(1), 101–115. 10.1016/j.rasd.2006.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R, Davis R, & Hill E (2013). The Effects of Autism and Alexithymia on Physiological and Verbal Responsiveness to Music. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(2), 432–444. 10.1007/s10803-012-1587-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R, Hill E, & Heaton P (2009). The subjective experience of music in autism spectrum disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 326–331. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley JM (1979). Music in the IEP: Therapy/Education. Journal of Music Therapy, 16(3), 111–126. 10.1093/jmt/16.3.111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvin J, & Warwick A (1978). Music therapy for the autistic child. Oxford University Press; https://global.oup.com/academic/product/music-therapy-for-the-autistic-child-9780198162766?cc=us&lang=en& [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrick LE, & Lickliter R (2004). Infants’ perception of rhythm and tempo in unimodal and multimodal stimulation: a developmental test of the intersensory redundancy hypothesis. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 4(2), 137–147. 10.3758/CABN.4.2.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, Kurzius-Spencer M, Zahorodny W, Robinson C, Rosenberg White, T., Durkin MS, Imm P, Nikolaou L, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Lee L-C, Harrington R, Lopez M, Fitzgerald RT, … Dowling NF (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck S, & Rieser J (2017). Joint music making makes preschoolers more likely to help a previously unknown adult: Examining the role of lyrics, joint movement, and synchrony.

- Bennett E, & Heaton P (2012). Is Talent in Autism Spectrum Disorders Associated with a Specific Cognitive and Behavioural Phenotype? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(12), 2739–2753. 10.1007/s10803-012-1533-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieleninik L, Geretsegger M, Mössler K, Assmus J, Thompson G, Gattino G, Elefant C, Gottfried T, Igliozzi R, Muratori F, Suvini F, Kim J, Crawford MJ, Odell-Miller H, Oldfield A, Casey Ó, Finnemann J, Carpente J, Park A-L, … Gold C (2017). Effects of Improvisational Music Therapy vs Enhanced Standard Care on Symptom Severity Among Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA, 318(6), 525 10.1001/jama.2017.9478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger D, Trost W, & Schön D (2013). Rhythm implicitly affects temporal orienting of attention across modalities. Acta Psychologica, 142(2), 238–244. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarata S, & Yoder P (2002). Language transactions during development and intervention: theoretical implications for developmental neuroscience. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 20(3–5), 459–465. 10.1016/s0736-5748(02)00044-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caria A, Venuti P, & De Falco S (2011). Functional and dysfunctional brain circuits underlying emotional processing of music in autism spectrum disorders. Cerebral Cortex, 21(12), 2838–2849. 10.1093/cercor/bhr084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cason N, & Schön D (2012). Rhythmic priming enhances the phonological processing of speech. Neuropsychologia, 50(11), 2652–2658. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheever T, Taylor A, Finkelstein R, Edwards E, Thomas L, Bradt J, Holochwost SJ, Johnson JK, Limb C, Patel AD, Tottenham N, Iyengar S, Rutter D, Fleming R, & Collins FS (2018). NIH/Kennedy Center Workshop on Music and the Brain: Finding Harmony. Neuron, 97(6), 1214–1218. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenausky K, Norton A, Tager-Flusberg H, & Schlaug G (2016). Auditory-Motor Mapping Training: Comparing the Effects of a Novel Speech Treatment to a Control Treatment for Minimally Verbal Children with Autism. PLOS ONE, 11(11), e0164930 10.1371/journal.pone.0164930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenausky KV, Norton AC, & Schlaug G (2017). Auditory-Motor Mapping Training in a More Verbal Child with Autism. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 426 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chern A, Tillmann B, Vaughan C, & Gordon RL (2018). New evidence of a rhythmic priming effect that enhances grammaticality judgments in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 173, 371–379. 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, & Schultz RT (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 231–239. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli LK, Einarson KM, & Trainor LJ (2014). Interpersonal synchrony increases prosocial behavior in infants. Developmental Science, 17(6), 1003–1011. 10.1111/desc.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli LK, Jurewicz ZB, & Trehub SE (2019). Effects of Maternal Singing Style on Mother–Infant Arousal and Behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 1–8. 10.1162/jocn_a_01402 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cirelli LK, & Trehub SE (2018). Infants help singers of familiar songs. Music & Science, 1, 1–11. 10.1177/2059204318761622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli LK, Trehub SE, & Trainor LJ (2018). Rhythm and melody as social signals for infants. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1423(1), 66–72. 10.1111/nyas.13580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli LK, Wan SJ, Spinelli C, & Trainor LJ (2017). Effects of Interpersonal Movement Synchrony on Infant Helping Behaviors. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34(3), 319–326. 10.1525/mp.2017.34.3.319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FS, & Fleming R (2017). Sound health: An NIH-Kennedy Center initiative to explore music and the mind. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association, 317(24), 2470–2471. 10.1001/jama.2017.7423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner CM, White SW, Scahill L, & Mazefsky CA (2020). The role of emotion regulation and core autism symptoms in the experience of anxiety in autism. Autism!: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 1362361320904217 10.1177/1362361320904217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cook A, Ogden J, & Winstone N (2018). The impact of a school-based musical contact intervention on prosocial attitudes, emotions and behaviours: A pilot trial with autistic and neurotypical children. Autism, 136236131878779 10.1177/1362361318787793 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Corbeil M, Trehub SE, & Peretz I (2016). Singing Delays the Onset of Infant Distress. Infancy, 21(3), 373–391. 10.1111/infa.12114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming R, Wilson A, Leong V, Colling LJ, & Goswami U (2015). Awareness of Rhythm Patterns in Speech and Music in Children with Specific Language Impairments. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9(December), 672 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custodero LA (2006). Singing Practices in 10 Families with Young Children. Journal of Research in Music Education, 54(1), 37–56. 10.1177/002242940605400104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, & Adams A (1984). Imitation and social responsiveness in autistic children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12(2), 209–225. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6725782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePape A-MR, Hall GBC, Tillmann B, & Trainor LJ (2012). Auditory Processing in High-Functioning Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e44084 10.1371/journal.pone.0044084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickie VA, Baranek GT, Schultz B, Watson LR, & McComish CS (2009). Parent reports of sensory experiences of preschool children with and without autism: A qualitative study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(2), 172–181. 10.5014/ajot.63.2.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffier N, Herrmann CS, & Schirmer A (2015). Auditory rhythms entrain visual processes in the human brain: Evidence from evoked oscillations and event-related potentials. NeuroImage, 111, 267–276. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg S, & Funderburk B (2011). Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Protocol. PCIT International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D, & Perkins R (2018). The effects of mother–infant singing on emotional closeness, affect, anxiety, and stress hormones. Music & Science, 1, 205920431774574 10.1177/2059204317745746 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster CB (2017). Arbitrary and natural reinforcement In Behavior therapy with children (pp. 37–43). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Franchini M, Armstrong VL, Schaer M, & Smith IM (2018). Initiation of joint attention and related visual attention processes in infants with autism spectrum disorder: Literature review. Child Neuropsychology, 1–31. 10.1080/09297049.2018.1490706 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fujioka T, Ross B, & Trainor LJ (2015). Beta-Band Oscillations Represent Auditory Beat and Its Metrical Hierarchy in Perception and Imagery. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(45), 15187–15198. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2397-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geretsegger M, Elefant C, Ssler K. a, & Gold C (2014). Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, Issue 6 Art. No.: CD004381. 10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn JA, Henry MJ, & McAuley JD (2011). FMRI investigation of cross-modal interactions in beat perception: Audition primes vision, but not vice versa. NeuroImage, 54(2), 1231–1243. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn JA, & McAuley JD (2009). Neural bases of individual differences in beat perception. NeuroImage, 47(4), 1894–1903. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe F, & Frith U (2010). Autism and Talent. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, & Watson SL (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642. 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P, Hermelin B, & Pring L (1998). Autism and Pitch Processing: A Precursor to Savant Musical Ability? Music Perception, 15(3), 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton Pamela. (2003). Pitch memory, labelling and disembedding in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 44(4), 543–551. 10.1111/1469-7610.00143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton Pamela. (2005). Interval and contour processing in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(6), 787–793. 10.1007/s10803-005-0024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KL, Lerch J, Norton A, Forgeard M, Winner E, Evans AC, & Schlaug G (2009). Musical training shapes structural brain development. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(10), 3019–3025. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilari B, Moura A, & Bourscheidt L (2011). Between interactions and commodities: musical parenting of infants and toddlers in Brazil. Music Education Research, 13(1), 51–67. 10.1080/14613808.2011.553277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, & Dvortcsak A (2010). Teaching social communication to children with autism. The Guilford Press, pp.47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, & Gergans S (2006). The effect of a parent-implemented imitation intervention on spontaneous imitation skills in young children with autism. 1–13. 10.1016/j.ridd.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ingersoll B, & Schreibman L (2009). Reciprocal Imitation Training: A naturalistic behavioral approach to teaching imitation in young children with autism In Reed P (Ed.), Behavioral theories and interventions for autism. Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen JR, Repp BH, & Patel AD (2009). Top-down control of rhythm perception modulates early auditory responses. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 58–73. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04579.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JC, Jong J, Bilkey D, Whitehouse H, Zollmann S, McNaughton C, & Halberstadt J (2018). Synchrony and Physiological Arousal Increase Cohesion and Cooperation in Large Naturalistic Groups. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 1–8. 10.1038/s41598-017-18023-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EJH, Venema K, Earl RK, Lowy R, & Webb SJ (2017). Infant social attention: an endophenotype of ASD-related traits? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(3), 270–281. 10.1111/jcpp.12650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juslin PN, & Västfjäll D (2008). Emotional responses to music: The need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31(05), 559–575; discussion 575–621. 10.1017/S0140525X08005293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP, Hancock TB, & Nietfeld JP (2000). The Effects of Parent-Implemented Enhanced Milieu Teaching on the Social Communication of Children Who Have Autism. Early Education & Development, 11(4), 423–446. 10.1207/s15566935eed1104_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L (1943). Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact. Nervous Child, 217–250. [PubMed]

- Kasari C, Freeman S, & Paparella T (2006). Joint attention and symbolic play in young children with autism!: a randomized controlled intervention study. 6, 611–620. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Gulsrud A, Freeman S, Paparella T, & Hellemann G (2012). Longitudinal follow-up of children with autism receiving targeted interventions on joint attention and play. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(5), 487–495. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern P, Wolery M, & Aldridge D (2007). Use of Songs to Promote Independence in Morning Greeting Routines For Young Children With Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(7), 1264–1271. 10.1007/s10803-006-0272-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Wigram T, & Gold C (2008). The effects of improvisational music therapy on joint attention behaviors in autistic children: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(9), 1758–1766. 10.1007/s10803-008-0566-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird E, Stewart C, & Tchanturia K (2019). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis In European Psychiatry (Vol. 55, pp. 80–89). Elsevier Masson SAS; 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner S, & Tomasello M (2009). Joint drumming: Social context facilitates synchronization in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102(3), 299–314. 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Ashbaugh K, & Koegel RL (2016). Pivotal response treatment In Early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder (pp. 85–112). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- LaGasse AB (2015). Effects of a music therapy group intervention on enhancing social skills in children with autism. Journal of Music Therapy, 51(3), 250–275. 10.1093/jmt/thu012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large EW, & Jones MR (1999). The dynamics of attending: How People Track Time-Varying Events. In Psychological Research (Vol. 106, Issue 1, pp. 119–159). 10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lense MD (2018). Musical Engagement and Social Behavior in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Manuscript under review.

- Lense Miriam Diane, & Jones WR (2016). Beat-based entrainment during infant-directed singing supports social engagement. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Music Perception & Cognition (ICMPC14). [Google Scholar]

- Leong V, & Goswami U (2014). Assessment of rhythmic entrainment at multiple timescales indyslexia: Evidence for disruption to syllable timing. Hearing Research, 308, 141–161. 10.1016/j.heares.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewkowicz DJ (2003). Learning and Discrimination of Audiovisual Events in Human Infants: The Hierarchical Relation Between Intersensory Temporal Synchrony and Rhythmic Pattern Cues. Developmental Psychology, 39(5), 795–804. 10.1037/0012-1649.39.5.795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HA (2010). Use of Music in the Applied Behavior Analysis Verbal Behavior Approach for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Music Therapy Perspectives, 28, 95–105. https://academic.oup.com/mtp/article-abstract/28/2/95/1056315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour R, Dovi AT, Lane DM, Loveland KA, & Pearson DA (2017). ADHD severity as it relates to comorbid psychiatric symptomatology in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 60, 52–64. 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchena A. de, & Eigsti I-M (2010). Conversational gestures in autism spectrum disorders: asynchrony but not decreased frequency. Autism Research, 3, 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Herrington J, Siegel M, Scarpa A, Maddox BB, Scahill L, & White SW (2013). The Role of Emotion Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(7), 679–688. 10.1016/J.JAAC.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley JD, & Fromboluti EK (2014). Attentional entrainment and perceived event duration. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1658), 20130401–20130401. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFerran KS, Thompson G, & Bolger L (2016). The impact of fostering relationships through music within a special school classroom for students with autism spectrum disorder: an action research study. Educational Action Research, 24(2), 241–259. 10.1080/09650792.2015.1058171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehr SA, Song LA, & Spelke ES (2016). For 5-Month-Old Infants, Melodies Are Social. Psychological Science, 1–16. 10.1177/0956797615626691 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller JE, Carlson LA, & McAuley JD (2013). When What You Hear Influences When You See: listening to an auditory rhythm influences the temporal allocation of visual attention. Psychological Science, 24(1), 11–18. 10.1177/0956797612446707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill TH, Dilley LC, McAuley JD, & Pitt MA (2014). Distal rhythm influences whether or not listeners hear a word in continuous speech: Support for a perceptual grouping hypothesis. Cognition, 131(1), 69–74. 10.1016/j.cognition.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata T, & Trehub SE (2004). Infants’ responsiveness to maternal speech and singing. Infant Behavior and Development, 27(4), 455–464. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2004.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overy K, & Molnar-Szakacs I (2009). Being together in time: Musical experience and the mirror neuron system. Music Perception, 26(5), 489–504. 10.1525/mp.2009.26.5.489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AD (2011). Why would musical training benefit the neural encoding of speech? The OPERA hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 2(JUN), 1–14. 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriquin MA, Hartwig EM, Friedman BH, Porges SW, & Scarpa A (2019). Autonomic response in autism spectrum disorder: Relationship to social and cognitive functioning. Biological Psychology, 145, 185–197. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2019.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Augustyn A, Klin A, & Volkmar FR (2005). Perception and production of prosody by speakers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(2), 205–220. 10.1007/s10803-004-1999-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellecchia M, Connell JE, Beidas RS, Xie M, Marcus SC, & Mandell DS (2015). Dismantling the Active Ingredients of an Intervention for Children with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(9), 2917–2927. 10.1007/s10803-015-2455-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz I, & Vuvan DT (2017). Prevalence of congenital amusia. European Journal of Human Genetics, 25(5), 625–630. 10.1038/ejhg.2017.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politimou N, Stewart L, Müllensiefen D, & Franco F (2018). Music@Home: A novel instrument to assess the home musical environment in the early years. PLoS ONE, 13(4), 1–23. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prizant BM, Wetherby AM, Rubin E, & Laurent AC (2003). The SCERTS Model: A Transactional, Family Centered Approach to Enhancing Communication and Socioemotional Abilities of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Infants and Young Children, 16(4), 296–316. 10.1097/00001163-200310000-00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintin E-M, Bhatara A, Poissant H, Fombonne E, & Levitin DJ (2011). Emotion perception in music in high-functioning adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(9), 1240–1255. 10.1007/s10803-010-1146-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay G (2015). Functional data analysis for profiling of vocal development in ASD. American-Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger JJ (1978). Generalization of Cooperative Behavior Across Classroom Situations. The Journal of Special Education, 12(2), 209–217. 10.1177/002246697801200212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samson AC, Wells WM, Phillips JM, Hardan AY, & Gross JJ (2015). Emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from parent interviews and children’s daily diaries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 56(8), 903–913. 10.1111/jcpp.12370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaug G, Marchina S, & Norton A (2009). Evidence for plasticity in white-matter tracts of patients with chronic broca’s aphasia undergoing intense intonation-based speech therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169(1), 385–394. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04587.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaug G, Norton A, Marchina S, Zipse L, & Wan CY (2010). From singing to speaking: Facilitating recovery from nonfluent aphasia. Future Neurology, 5(5), 657–665. 10.2217/fnl.10.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, Landa R, Rogers SJ, McGee GG, Kasari C, Ingersoll B, Kaiser AP, Bruinsma Y, McNerney E, Wetherby A, & Halladay A (2015). Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions: Empirically Validated Treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2411–2428. 10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg ET, & Silverman MJ (2017). Parent perceptions of music therapy in an on-campus clinic for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Musicae Scientiae, 21(1), 98–112. 10.1177/1029864916644420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Hong J, Smith LE, Almeida DM, Coe C, & Stawski RS (2010). Maternal cortisol levels and behavior problems in adolescents and adults with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(4), 457–469. 10.1007/s10803-009-0887-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharda M, Midha R, Malik S, Mukerji S, & Singh NC (2015). Fronto-Temporal connectivity is preserved during sung but not spoken word listening, across the autism spectrum. Autism Research, 8(2), 174–186. 10.1002/aur.1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharda M, Silani G, Specht K, Tillmann J, Nater U, & Gold C (2019). Music therapy for children with autism: investigating social behaviour through music. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 10.1016/s2352-4642(19)30265-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sharda M, Tuerk C, Chowdury R, Jamey K, Fostern N, Custo-Blanh M, Tan M, Nadig A, & Hyde K (2018). Music improves social communication and brain connectivity outcomes in children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. 10.1093/annonc/mdy139/4983109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shriberg LD, Paul R, McSweeny JL, Klin A, Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, C., B., D., B., K., E., W., F., P., F., L., G., B., G., P., H., L., K., L., K., A., K., D., S. L., D., S. L., … E., W. (2001). Speech and Prosody Characteristics of Adolescents and Adults With High-Functioning Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 44(5), 1097 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/087) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreewichian P (2019). Exploring the Influence of Music Intervention on Social and Communication Development in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mahidol Music Journal, 2(1), 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Eigsti I, Gifford T, & Bhat A (2016). The effects of embodied rhythm and robotic interventions on the spontaneous and responsive verbal communication skills of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum, 27, 54–72. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1750946716300435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan SM, Kaur M, Park IK, Gifford TD, Marsh KL, & Bhat AN (2015). The Effects of Rhythm and Robotic Interventions on the Imitation/Praxis, Interpersonal Synchrony, and Motor Performance of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Autism Research and Treatment, 2015, 1–18. 10.1155/2015/736516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson RA, Siemann JK, Woynaroski TG, Schneider BC, Eberly HE, Camarata SM, & Wallace MT (2014). Evidence for Diminished Multisensory Integration in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(12), 3161–3167. 10.1007/s10803-014-2179-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss K, Vicari S, Valeri G, D’Elia L, Arima S, & Fava L (2012). Parent inclusion in Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention: The influence of parental stress, parent treatment fidelity and parent-mediated generalization of behavior targets on child outcomes. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(2), 688–703. 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y-H (2014). Content congruency and its interplay with temporal synchrony modulate integration between rhythmic audiovisual streams. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 8(December), 92 10.3389/fnint.2014.00092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GA (2017). Long-term perspectives of family quality of life following music therapy with young children on the autism spectrum: A phenomenological study. Journal of Music Therapy, 54(4), 432–459. 10.1093/jmt/thx013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor LJ, & Cirelli L (2015). Rhythm and interpersonal synchrony in early social development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337(1), 45–52. 10.1111/nyas.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trehub SE, & Cirelli LK (2018). Precursors to the performing arts in infancy and early childhood. Progress in Brain Research, 237, 225–242. 10.1016/BS.PBR.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trehub SE, Ghazban N, & Corbeil M (2015). Musical affect regulation in infancy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337(1), 186–192. 10.1111/nyas.12622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trehub SE, & Gudmundsdottir HR (2015). Mothers as singing mentors for infants. The Oxford Handbook of Singing, online publication. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199660773.013.25 [DOI]

- Trehub SE, Plantinga J, Brcic J, & Nowicki M (2013). Cross-modal signatures in maternal speech and singing. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(NOV), 1–9. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trehub SE, Plantinga J, & Russo FA (2016). Maternal Vocal Interactions with Infants: Reciprocal Visual Influences. Social Development, 25(3), 665–683. 10.1111/sode.12164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C (1999). Musicality and the intrinsic motive pulse: evidence from human psychobiology and infant communication. Musicae Scientiae, 3(1_suppl), 155–215. 10.1177/10298649000030S109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tunçgenç B, & Cohen E (2018). Interpersonal movement synchrony facilitates pro-social behavior in children’s peer-play. Developmental Science, 21(1), 1–9. 10.1111/desc.12505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer AL, Hepburn S, & McMahon Griffith E (2017). Remembering parents in parent-mediated early intervention: An approach to examining impact on parents and families. Autism, 21(1), 5–17. 10.1177/1362361315622411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan CY, Bazen L, Baars R, Libenson A, Zipse L, Zuk J, Norton A, & Schlaug G (2011). Auditory-motor mapping training as an intervention to facilitate speech output in non-verbal children with autism: A proof of concept study. PLoS ONE, 6(9), 1–7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan CY, & Schlaug G (2010). Neural pathways for language in autism: the potential for music-based treatments. Future Neurology, 5(6), 797–805. 10.2217/fnl.10.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens N, & Gordon RL (2018). The case for treatment fidelity in active music interventions: why and how. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1423(1), 219–228. 10.1111/nyas.13639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse MH, Tidhar D, & Cross I (2016). Effects on inter-personal memory of dancing in time with others. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(February), 167 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo GE, & Kim SJ (2018). Dyadic Drum Playing and Social Skills: Implications for Rhythm-Mediated Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Music Therapy. 10.1093/jmt/thy013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman E, & Lahav A (2012). The multisensory brain and its ability to learn music. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1252(1), 179–184. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]