Abstract

There has been no clear consensus on the optimal consolidation periods following HBeAg seroconversion (SC) in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. Our study aimed to prospectively compare relapse rates between 12 months’ and 18 months’ consolidation periods to see whether or not there is beneficial durability of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) therapy with longer consolidation periods.

We enrolled a total of 137 HBeAg-positive Asian CHB patients treated with TDF monotherapy. Forty-six patients achieved HBeAg SC. Then, they were randomly assigned to consolidation period of either 12 months (group A) or 18 months (group B). After stopping TDF therapy, all patients were followed up for 12 months.

Thirteen patients (56.5%) relapsed in group A and 12 patients (52.2%) relapsed in group B after 12 months’ follow-up (P = .958). Pretreatment HBsAg level is the only significant predictor for off-therapy recurrence by univariate analysis (P = .024). Baseline HBeAg >1000 S/CO in group B patients were significantly less likely to relapse than those of group A (P = .046). Baseline alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >133 U/L could significantly predict occurrence of HBeAg SC (P = .008; 95% CI: 0.545–0.763; AUC: 0.654).

Overall, a prolonged consolidation period has no positive effect on TDF therapy on sustained viral suppression in HBeAg-positive Asian CHB patients. However, a prolonged consolidation period was beneficial to patients with high baseline semi-quantitative HBeAg levels in terms of off-treatment durability. Baseline ALT > 133 U/L could significantly predict the occurrence of HBeAg SC.

Keywords: HBV DNA, hepatitis B e antigen, hepatitis B surface antigen

1. Introduction

A recent study reported that 240 million individuals are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV). Chronic HBV infection is a major cause of chronic hepatitis B (CHB), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.[1] The definition of CHB infection is persistent HBV infection accompanied by the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the serum of patients lasting >6 months.[2] It is reasonable to assume that most patients with CHB infection were infected in early infancy.[2–4]

The presently available antiviral medications include interferon (interferon-α and pegylated interferon-α) and nucleoside or nucleotide analogues (NAs; entecavir, adefovir dipivoxil, telbivudine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate [TDF], and lamivudine). Guidelines established by the European Association for the Study of the Liver, Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver, and American Association for the Study of Liver Disease for the treatment of CHB advocate that a satisfactory endpoint is a sustained off-therapy virological response with sustained anti-hepatitis B e (HBeAb) seroconversion (SC) in HBe antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients. After achieving this endpoint, these guidelines recommend continuous consolidation therapy for 6 to 12 months before discontinuing NAs. It is clinically informative that the duration of consolidation therapy is linked to the relapse rates in HBeAg-positive CHB patients who have achieved HBeAg SC.[4,5]

Generally speaking, HBeAg positivity correlates with a high level of HBV DNA.[6,7] Data suggest that extending treatment with NAs following SC, i.e., consolidation therapy for an additional period, increases durability.[8,9] However, the potential additional benefits of continuous TDF therapy to sustained viral suppression have not been thoroughly studied. This prospective study investigated the efficacy of prolonged TDF monotherapy in treatment-naïve CHB patients to determine whether continuous TDF therapy offers better viral suppression after HBeAg SC.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients and treatment

From 2013 to 2018, we conducted a prospective multi-center, single-arm, and open-label study, which included a total of 137 HBeAg-positive patients (male: 84, female: 53; mean age: 48.6 ± 11.8 years) treated with TDF monotherapy (dose: 300 mg/day). All patients enrolled in this study met the following inclusion criteria: age 20 to 75 years; positivity for serum HBsAg for ≥6 months; elevated levels (greater than the upper limit of normal) of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) on two occasions ≥3 months apart; HBV DNA (>20,000 IU/mL) for more than 6 months; detection of HBeAg; cirrhosis or significant liver fibrosis detected via fibrosis-4 index and imaging technique tests in patients with ALT < 2 ULN. The exclusion criteria were patients who had coinfection with hepatitis A, C, D, or E viruses or human immunodeficiency virus; co-existing liver disease, such as Wilson's disease, autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma; undergone treatment with other antiviral drugs within 6 months.

2.2. Study protocols

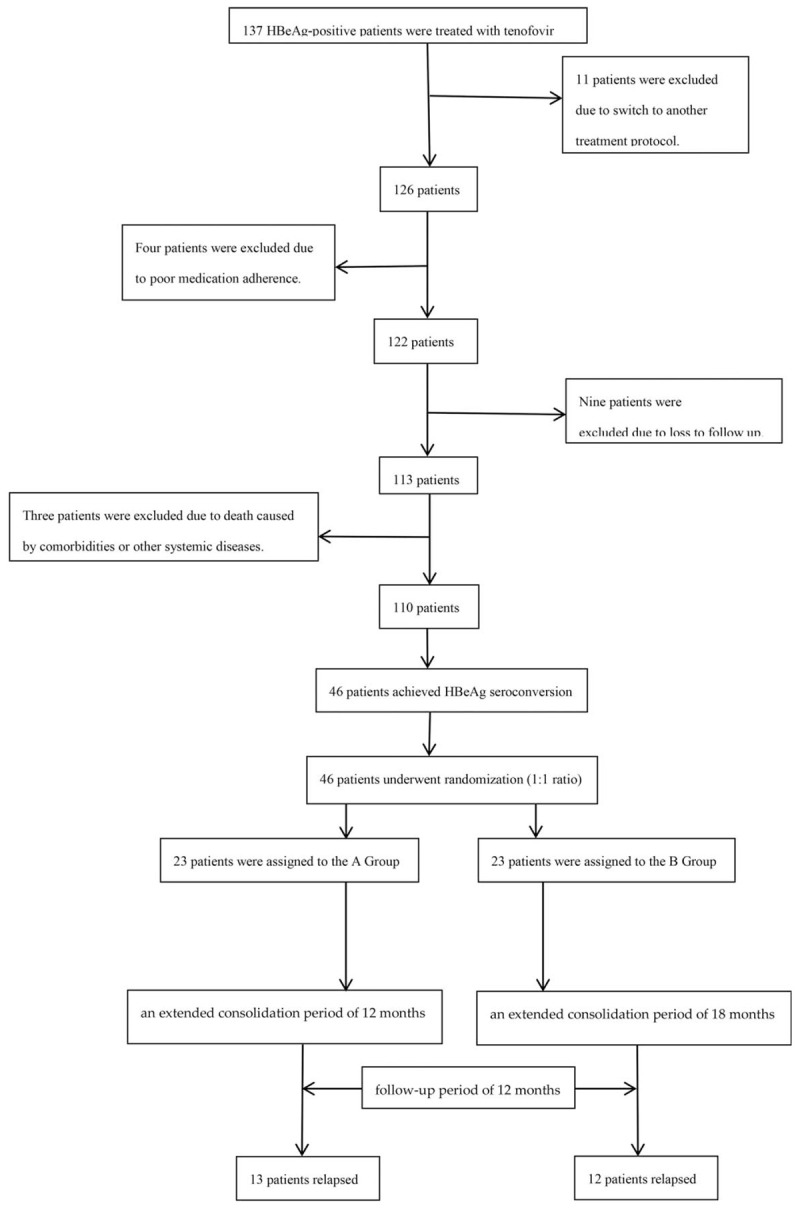

Eleven patients were excluded due to having switched to another treatment protocol. Four patients were excluded due to poor medication adherence. Nine patients were excluded due to loss to follow-up. Finally, three patients were excluded due to death caused by comorbidities or other systemic diseases.

The remaining 110 patients completed the study and subsequent follow-up. Because, we used a randomization approach in our study, the randomization sequence was developed using Excel 2007 with a 1:1 allocation by an independent researcher. Accordingly, the patients were randomly assigned to an extended consolidation period of 12 months (group A) or 18 months (group B) following HBeAg SC plus undetectable HBV-DNA in the serum. Antiviral therapy was discontinued after HBeAg SC and HBV DNA negativity, followed by consolidation therapy for 12 months or 18 months. After discontinuation of TDF therapy, all patients were followed up for 12 months.

The study endpoint was serologic and virologic recurrence after discontinuation of antiviral treatment. Serologic recurrence was defined as a reappearance of HBeAg positivity after HBeAg SC. Virologic recurrence was defined as an increase in the level of HBV–DNA. The protocol of this study was in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committees of all participating hospitals. All patients provided written informed consent prior to initiating treatment. The present study was in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. An identification code (NCT01732354) was provided by the ClinicalTrials.gov Protocol Registration and Results System.

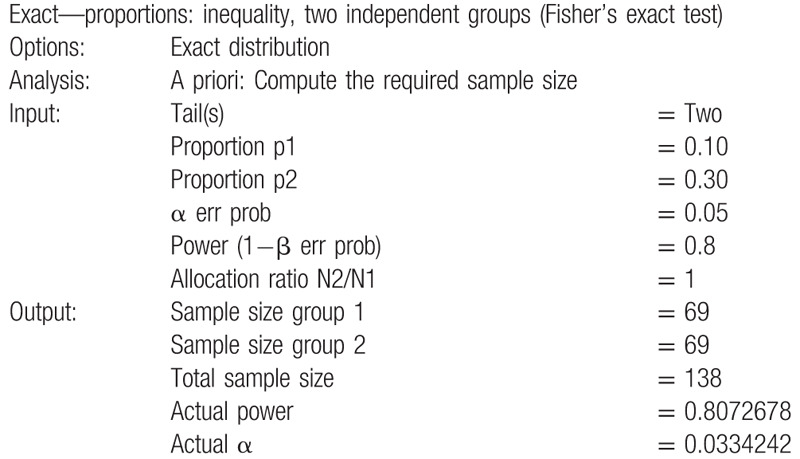

2.3. Sample size calculation

We use G∗power software[10] to perform sample size estimation as follows:

A total of a sample size of 138 was obtained. One subject decided to withdraw from present research prior to the beginning of the study due to personal reasons. As such, 137 eligible subjects were enrolled.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means, where appropriate. The level of HBV DNA was logarithmically transformed for analysis. The Student's t test was used for between-group comparisons of continuous variables.

Multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression to identify factors associated with virologic relapse or HBeAg reconversion after discontinuing TDF monotherapy. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to assess the relative risk confidence.

Independent risk factors predicting the achievement of HBeAg SC were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression models. The cumulative recurrence rates of viral recurrence, after HBeAg SC, were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) version 18.0. A P-value of <.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

After excluding 27 patients, a total of 137 patients with CHB were recruited into the study. Of those, 110 patients completed the study, and were followed up for 1 year after discontinuation of TDF treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing enrollment, randomization, and follow-up of study participants.

The mean baseline serum data showed the following: AST level, 157.8 ± 199.9 IU/L (range: 27–1107); ALT level, 276.1 ± 302.3 (range: 30–1344) IU/L; HBsAg level, 1,337,231 ± 12,422,695 IU/mL (range: 6.1–117,879,160); HBeAg level: 12,805.2 ± 141,510.6 S/CO (range: 1.1–1,650,940), and HBV DNA level, 7.3 ± 1.2 (range: 3.2–9.1) log10 copies/mL. The mean duration of treatment with TDF was 28.7 ± 11.8 (range: 14–53) months. The mean duration of HBeAg SC was 16.7 ± 11.5 months after the initiation of treatment with TDF. The mean time from HBeAg loss to HBeAg SC was 2.4 ± 1.5 months. The mean time from HBeAg SC to relapse was 22.7 ± 10 months.

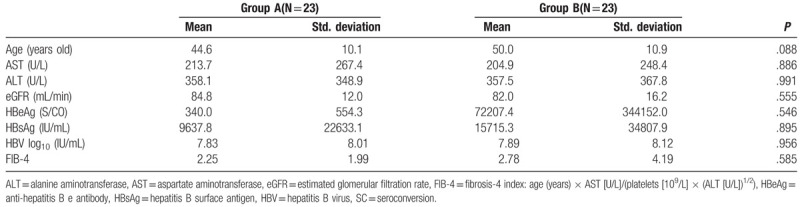

A total of 46 HBeAg SC patients were randomly assigned to group A (n = 23) and group B (n = 23) for 12- and 18-month consolidation therapy, respectively. Table 1 shows the comparative analysis of pre-treatment factors between patients with HBeAg SC in groups A and B. The two groups did not show differences in baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of pretreatment factors between groups A and B in patients with HBeAg SC.

3.2. Efficacy

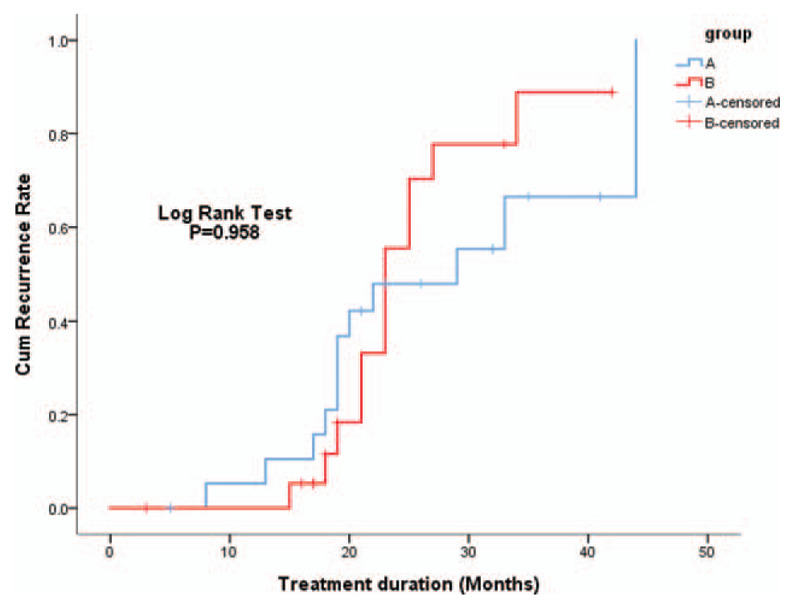

At the 12-month follow-up, 13 (56.5%) and 12 (52.2%) patients relapsed in group A and group B, respectively. The Kaplan–Meier method did not reveal a difference in the relapse rates between group A and group B (P = .958) (Fig. 2). Among the patients who relapsed, HBeAg seroreversion occurred in 13 of the 46 anti-HBe positive patients (28.3%).

Figure 2.

Cumulative recurrence rates were compared between groups A and B by the Kaplan–Meier method. Logrank test showed no significant difference between the two groups (P = .958).

3.3. Factors associated with responses

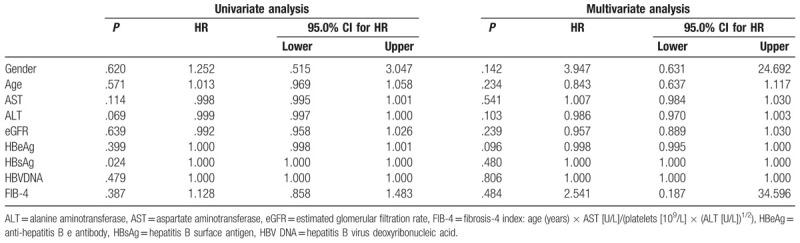

According to the univariate analysis, the pre-treatment level of HBsAg was the only significant predictor for off-therapy recurrence (P = .024). However, the multivariate analysis demonstrated that none of the pre-treatment factors could predict off-therapy recurrence (Table 2). Furthermore, the magnitude of serum HBsAg levels reduction from baseline did not differ significantly at 12 months post-treatment between relapsers and non-relapsers using the Mann–Whitney test (P = .924).

Table 2.

Neither univariate nor multivariate analyses by Cox regression showed any significant predictor for relapse.

3.4. Predictive role of HBeAg

Based on the dynamics of change in the semi-quantitative levels of HBeAg, patients who exhibited an HBeAg decline <25% from baseline after 6 months of treatment showed a significantly higher relapse rate compared with those who showed a decline ≥25% (P < .001). We further separated the levels of HBeAg into a sequence of graded status in groups A and B. The patients with baseline HBeAg level >1000 S/CO in group B had a significantly lower risk of relapse than those in group A (P = .046).

3.5. Predictive role of ALT

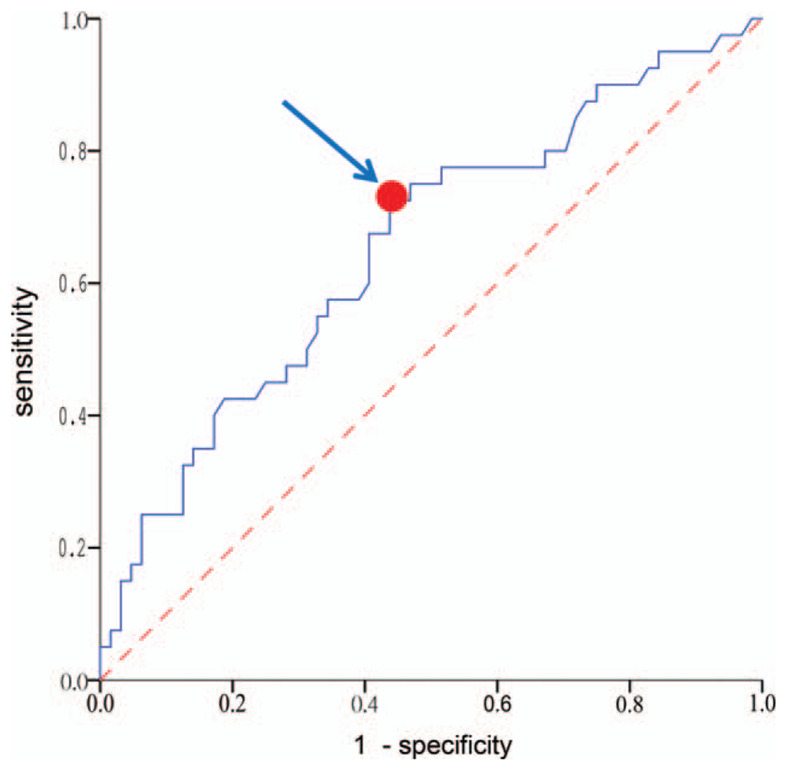

Patients with a decline in the level of ALT ≥90% from baseline to 6 months of treatment had a lower risk of relapse than those with a decline <90%. Based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (Fig. 3), a baseline level of ALT >133 U/L could significantly predict the occurrence of HBeAg SC (P = .008; 95% CI: 0.545–0.763; area under the curve: 0.654) with a positive predictive value of 0.51 (95% CI: 0.38–0.64) and negative predictive value of 0.77 (95% CI: 0.64–0.87). None of the patients experienced decompensation after relapse.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve statistics for a baseline level of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >133 U/L could significantly predict the occurrence of HBeAg SC (P = .008; 95% CI: 0.545–0.763; area under the curve: 0.654). Arrow indicates the best cutoff point of highest sensitivity while maintaining high specificity.

4. Discussion

Many published results from predominantly Caucasian CHB cohorts have demonstrated that there have been reports of the persistence of HBeAg SC in 80% to 90% of patients, whereas in Asian studies relapse rates as high as 68% have been reported.[11,12] Generally speaking, in Asian patients, it is difficult to achieve HBeAg SC through treatment with NAs, and SC is less durable even with extensive (1 year) consolidation therapy.[13–18] Despite the recommendations from current guidelines for consolidation periods of 6 to 12 months after HBeAg SC,[1,19,20] virologic or serologic relapse remains unavoidable.

To the best of our knowledge, thus far, no prospective longitudinal study has directly compared two different consolidation periods of TDF monotherapy in terms of off-treatment durability. In our study, 56.5% and 52.2% of patients who received consolidation therapy for 12 and 18 months, respectively, relapsed within 1 year of follow-up. Given these data, there was no statistically significant difference between the two consolidation periods, indicating that longer consolidation therapy with TDF did not exert obvious beneficial effects on off-treatment durability. However, it may be argued that prolonged consolidation or follow-up periods maybe not being long enough to detect significant differences between the two groups. Recently published results showed that most relapses occurred within the first year after discontinuing antiviral therapy.[15,17] Therefore, it is evident that the first year after discontinuation of antiviral therapy is an important period during which the vast majority of off-treatment virologic relapses occur. Thus, follow-up for 1 year after discontinuation of treatment with TDF is appropriate to determine the durability of TDF.

Studies have shown that the best treatment endpoint for CHB is HBsAg SC[1,19]; however, it is only achieved in a small proportion of patients. Therefore, long-term treatment with NAs is inevitable.[21] However, this type of treatment is limited by safety concerns and unsatisfactory patient compliance. Another issue of great concern is that long-term NAs therapy is associated with a financial burden in many Asian counties where the costs of anti-viral treatment are not entirely reimbursed.[22]

Given the aforementioned reasons, several investigators have been attempting to identify useful predictors, which could define the optimal time point for discontinuation of treatment with NAs offering satisfactory off-therapy durability.[23–25]

Therefore, in this study, we highlighted this critical issue in HBeAg-positive patients and aimed to clarify uncertainty: what is the optimal duration of a consolidation period for treatment with TDF? Despite the availability of numerous retrospective studies,[25–27] thus far, no prospective studies have been conducted.

Current guidelines recommend that treatment with NAs in HBeAg-positive patients may be discontinued after the emergence of HBeAg SC and 6 to 12 months of consolidation therapy.[28] Although prolonged therapy with NAs may reduce the rate of relapse,[15,17,29] there is limited information regarding the long-term outcomes in terms of cost-effectiveness. Identification of patients with high-risk of relapse (i.e., those who require longer consolidation therapy after cessation of treatment with NAs) is mandatory for determining the optimal anti-HBV therapeutic strategy. This strategy is greatly dependent on many pre-treatment and on-treatment serological and virological factors, such as age, genotype, serum liver function tests, HBV viral loads, HBsAg levels, and duration of consolidation therapy.[30–32] In our study, the magnitude of benefit was not substantially greater in patients who received extensive consolidation TDF therapy (18 months) after HBeAg SC. In accordance with previously reported findings, the univariate analysis of our data revealed that the pre-treatment level of HBsAg is the only significant predictor of off-therapy recurrence.

The most noteworthy finding in our study was that the dynamics of change in the semi-quantitative level of HBeAg most probably contributed as a precise predictive factor for off-treatment relapse in patients treated with TDF. Patients with a limited reduction in the level of HBeAg (<25% from baseline) after 6 months of treatment showed a significantly higher relapse rate after discontinuing TDF therapy. This observation suggests that we may be able to safely cease antiviral therapy after 1 year of consolidation therapy in patients with a rapid reduction in the level of HBeAg within 6 months.

HBeAg SC is regarded as an initial step of immune clearance in the natural history of CHB. Moreover, HBeAg positivity correlates with a high level of HBV DNA; thus, it can be used as a marker for active viral replication.[33–35] However, HBeAg continues to be qualitatively assayed despite the fact that HBsAg is quantitatively detected. The level of HBeAg was evaluated using the S/CO, and HBeAg positivity was confirmed in those with an S/CO ≥1.0.[36] A sub-analysis showed that patients who received consolidation therapy for 18 months and had a baseline level of HBeAg >1000 S/CO experienced a significantly lower risk of relapse. In other words, a prolonged consolidation period was beneficial to patients with a high baseline semi-quantitative level of HBeAg in terms of off-treatment durability.

In addition to the level of HBeAg, baseline and dynamic changes in the level of ALT demonstrated its pre-treatment and on-treatment roles in predicting the occurrence of HBeAg SC. Invariably, in Asian patients, NA-induced HBeAg SC is more difficult to achieve and maintain and is associated with frequent relapses after discontinuation of treatment.[37,38] HBeAg SC is not sustained in most CHB patients regardless of the type of oral high-potency antiviral agent used (e.g., TDF). The present study investigated one of the larger prospective cohorts of HBeAg-positive patients treated with TDF until SC and conducted a comparison of two different consolidation periods before the cessation of treatment. However, this study was characterized by the following limitations:

-

1.

lack of virological sequence information; and

-

2.

all patients were Asian, thus our findings may not be applicable to non-Asian patients with CHB.

5. Conclusions

In this prospective randomized study, the non-inferior efficacy of TDF treatment on HBeAg-positive CHB patients with a consolidation period of 12 months compared to 18 months, which highlighted that a prolonged consolidation period of TDF therapy did not exert a positive effect on sustained viral suppression. Furthermore, patients with higher baseline HBeAg levels (>1000 S/CO) by semi-quantification assay needed longer consolidation periods to avoid relapses.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Uni-edit for editing and proofreading this manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Data curation: Chun-Hsiang Wang, Yuan-Tsung Tseng.

Formal analysis: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Funding acquisition: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Investigation: Chun-Hsiang Wang, Yuan-Tsung Tseng.

Methodology: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Project administration: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Resources: Chang Seok Bang, Young Joo Yang, Gwang Ho Baik.

Visualization: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Writing – original draft: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Writing – review & editing: Chun-Hsiang Wang.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase, CHB = chronic hepatitis B, CI = confidence interval, HBeAb = anti-hepatitis B e, HBeAg = HBe antigen, HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen, HBV = hepatitis B virus, OR = odds ratio, ROC = receiver operating characteristic, SC = seroconversion, STROBE = the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology, TDF = tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

How to cite this article: Wang CH, Chang KK, Lin RC, Kuo MJ, Yang CC, Tseng YT. Consolidation period of 18 months No Better at promoting off-treatment durability in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment than a 12 month period: A prospective randomized cohort study. Medicine. 2020;99:18(e19907).

Dr Chun-Hsiang Wang received a research grant from Gilead Sciences, Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 2009;50:661–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat 2004;11:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Liver Dis 2004;24:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, et al. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology 2007;45:1056–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hu P, Ren H. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis, B., virus, infection. J Hepatol 2012;57:167–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int 2016;10:1–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Merriman RB, Tran TT. AASLD practice guidelines: the past, the present, and the future. Hepatology 2016;63:31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Byun KS, Kwon OS, Kim JH, et al. Factors related to post-treatment relapse in chronic hepatitis B patients who lost HBeAg after lamivudine therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;20:1838–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee HW, Lee HJ, Hwang JS, et al. Lamivudine maintenance beyond one year after HBeAg seroconversion is a major factor for sustained virologic response in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;51:415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, et al. G∗Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Poynard T, Hou JH, Chutaputti A. Sustained durability of HBeAg seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B patients after treatment with telbivudine. J Hepatol 2008;48:S268. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Song BC, Suh DJ, Lee HC, et al. Hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion after lamivudine therapy is not durable in patients with chronic hepatitis B in Korea. Hepatology 2000;32:803–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jo K, Dodge JL, Wadley A. HBeAg seroconversion is lower in Asian versus non-Asian patients during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with tenofovir or entecavir. Hepatology 2013;58:669A. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee CM, Ong GY, Lu SN, et al. Durability of lamivudine-induced HBeAg seroconversion for chronic hepatitis B patients with acute exacerbation. J Hepatol 2002;37:669–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wang L, Liu F, Liu YD, et al. Stringent cessation criterion results in better durability of lamivudine treatment: a prospective clinical study in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients. J Viral Hepat 2010;17:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Song BC, Cui XJ, Cho YK, et al. New scoring system for predicting relapse after lamivudine-induced hepatitis B e-antigen loss in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatol Res 2009;39:1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fung J, Lai CL, Tanaka Y, et al. The duration of lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B: cessation versus continuation of treatment after HBeAg seroconversion. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1940–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jin YJ, Kim KM, Yoo DJ, et al. Clinical course of chronic hepatitis B patients who were off-treated after lamivudine treatment: analysis of 138 consecutive patients. Virol J 2012;9:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 2018;67:1560–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int 2012;6:531–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chevaliez S, Hézode C, Bahrami S, et al. Long-term hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) kinetics during nucleoside/nucleotide analogue therapy: finite treatment duration unlikely. J Hepatol 2013;58:676–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ridruejo E, Silva MO. Safety of long-term nucleos(t)ide treatment in chronic hepatitis B. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2012;11:357–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liang Y, Jiang J, Su M, et al. Predictors of relapse in chronic hepatitis B after discontinuation of antiviral therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:344–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Dai CY, Tseng TC, Wong GL, et al. Consolidation therapy for HBeAg positive Asian chronic hepatitis B patients receiving lamivudine treatment: a multicentre study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013;68:2332–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jeng WJ, Sheen IS, Chen YC, et al. Off-therapy durability of response to entecavir therapy in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology 2013;58:1888–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lee IC, Sun CK, Su CW, et al. Durability of nucleos(t)ide analogues treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ito K, Tanaka Y, Orito E, et al. Predicting relapse after cessation of Lamivudine monotherapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lee KM, Cho SW, Kim SW, et al. Effect of virological response on post-treatment durability of lamivudine-induced HBeAg seroconversion. J Viral Hepat 2002;9:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yeh CT, Hsu CW, Chen YC, et al. Withdrawal of lamivudine in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients after achieving effective maintained virological suppression. J Clin Virol 2009;45:114–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee JM, Ahn SH, Kim HS, et al. Quantitative hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B e antigen titers in prediction of treatment response to entecavir. Hepatology 2011;53:1486–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chen CH, Lu SN, Hung CH, et al. The role of hepatitis B surface antigen quantification in predicting HBsAg loss and HBV relapse after discontinuation of lamivudine treatment. J Hepatol 2014;61:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 2006;295:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jardi JR, Buti M, Rodriguez-Frias F, et al. The value of quantitative detection of HBV-DNA amplified by PCR in the study of hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol 1996;24:680–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rabbi FJ, Rezwan MK, Shirin T. HBeAg/anti-HBe, alanine aminotransferase and HBV DNA levels in HBsAg positive chronic carriers. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 2008;34:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hasan KN, Rumi MA, Hasanat MA, et al. Chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus in Bangladesh: a comparative analysis of HBV-DNA, HBeAg/anti-HBe, and liver function tests. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2002;33:110–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Alghamdi A, Aref N, El-Hazmi M, et al. Correlation between hepatitis B surface antigen titers and HBV DNA levels. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2013;19:252–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chien RN, Yeh CT, Tsai SL, et al. Determinants for sustained HBeAg response to lamivudine therapy. Hepatology 2003;38:1267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].van Nunen AB, Hansen BE, Suh DJ, et al. Durability of HBeAg seroconversion following antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B: relation to type of therapy and pretreatment serum hepatitis B virus DNA and alanine aminotransferase. Gut 2003;52:420–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]