Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) management differs dramatically between Iraqi public and private sectors; this variability is due to treatment access discrepancy. The aim of this consensus is to put for the first-time uniform recommendation on how to manage patients with T2DM taking in consideration the local obstacles in Iraq. These consensuses were approved by a group of Iraqi Internist and diabetologist from all over the country. Up-to-date and latest level of evidence was used throughout the recommendation.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, consensus, management, prediabetes, Iraq

Introduction

Insulin deficiency secondary to a progressive decline of ß-cell function or insulin resistance (or both) leads gradually to a chronic increase in blood glucose levels or diabetes.1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the major type of diabetes around the world. It is caused by the body’s ineffective use of insulin added to a slow progressive loss of pancreatic β-cells.2,3 Both types of diabetes may have the same symptoms, but in T2DM they are often less marked or absent. Subsequently, it may be a silent disease without manifestation for a long time, until complications occur.4 For many years, this type of diabetes was observed only in adults, but, based on recent World Health Organization (WHO) data, it is also increasingly manifesting in children.3

For the past 30 years, the world has experienced a continuous raise in the prevalence of diabetes particularly in low- and middle-income countries which marks the most rapid growth.3 Earlier onset of T2DM is described in children, potentially due to modernization of lifestyle.5 The prevalence of diabetes worldwide in 2017, is estimated to be 8.8% (425 million people) among the adult population as presented by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Among IDF regions, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has the second highest rate of diabetes and 9.2% prevalence. Between 2017 and 2045, it is estimated that diabetes prevalence will increase by 110% in the MENA region and will reach 629 million worldwide in 2045.6

Diabetes is a heavy burden disease. In 2017, the mortality rate due to diabetes reached 10.7% in adult patients (20-79 years). In MENA Region, diabetes accounts for 373 557 deaths (21 countries and territories including Iraq) and an estimate of 51.8% of deaths are due to diabetes in patients aged below 60; this puts the region in the highest second level among IDF regions.6 Despite the high prevalence of diabetes in the MENA region, data on diabetes progression and complications are scarce and only 2.9% of total global spending on diabetes is invested in the region.

Around 1.4 million of Iraqis have diabetes.3 Reported T2DM prevalence in Iraq ranges from 8.5% (IDF—age-adjusted) to 13.9%.3 A local study including more than 5400 people in the city of Basrah, Southern Iraq, reported a 19.7% age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes in subjects aged 19 to 94 years.7

In Iraq, there are insufficient epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) related to diabetes; therefore, it remains difficult to fully understand the prevalence of diabetes in Iraq and the most effective therapies for Iraqi population.

Considerations

A group of internists and diabetologist with high expertise in the treatment of T2DM met in Beirut, Lebanon on the 6 July 2018 to reach a consensus on the management of T2DM in adults in Iraq and develop clear country-specific practice guidelines. The expert panel reviewed international guidelines prior to the consensus meeting including the “American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Medical Care in diabetes 2018”8 “the management of hyperglycemia in T2DM 2018—a consensus report by the ADA” and the “European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)”9 and the “IDF (2017).”10 The main consensus’ objective was to develop clear practice guidelines that are specific to Iraq and to unify T2DM management in addition to support the training of junior physicians and guide GPs in the management of T2DM adults. The consensus statement excludes secondary diabetes, diabetes in children, type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes, management of cardiovascular risk, and identification or management of complications.

Challenges and Unmet Needs Specific to Type 2 Diabetes Management in Iraq

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) include several non-transmissible chronic diseases such as diabetes and Iraq has established goals to prevent and control these diseases. However, security challenges and political instability have made these goals difficult to reach.11 Healthcare funds are distributed equally across all specialties and not according to needs or future plans. NCDs are neglected by regional policy makers in Iraq who tend to allocate funds toward cancer treatment and vaccines.12 Changing lifestyle contributed to the rise of T2DM in younger population. In 2016, 15.2% of school aged children in Iraq were overweight and 12.1% of them were obese13 while another study conducted approximately 10 years earlier showed that 6% of the children were overweight and 1.3% of them were obese.14

Fitness facility and access to exercise opportunities still lack in Iraq and physical activity, particularly in women, is seen as shameful.15 Recent rapid economic development increased availability of cars, access to cheap labor, mechanization of farming equipment, and use of electronic devices (eg, TV, smart phones, and tablets)—all promoting a more sedentary lifestyle.16 In addition, poor urban planning and urban expansion are claimed to be the primary cause of rising levels of sedentary behavior and the lack of necessary infrastructure such as walking or cycling paths and warm temperatures during several months of the year deters patients from being physically active.17 Conversely, the westernization of taste, eating-out and the preference of salty food, especially among children and adolescents were widely spread in the Iraqi daily life and have led to an increased fast-food consumption.18

The primary care infrastructure and expertise are lacking in Iraq and healthcare provision relies heavily on secondary and tertiary care.19 Programs for early detection of hypertension, diabetes, and breast cancer were developed for primary care; however, their implementation was not successful.

Many Iraqi health ministers showed willingness to support primary care; however, this is a lengthy and complicated process that requires new legislation and budget allocation, in addition, there is a limited availability of therapies for T2DM in the Iraq public sector dispensaries. This result in a two-tier system where patient access to treatment modalities differs based on income.20

Consensus Recommendations for the Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults

Precise figures on where patients with diabetes are diagnosed in Iraq are not available; settings vary based on geographical location. Primary healthcare physician usually diagnose the majority of patients with T2DM when compared to secondary and tertiary care providers; however, the ratio varies across the country. Thus, the expert panel suggested the possibility of a program to be implemented in a primary care setting that could be managed by primary healthcare physician.

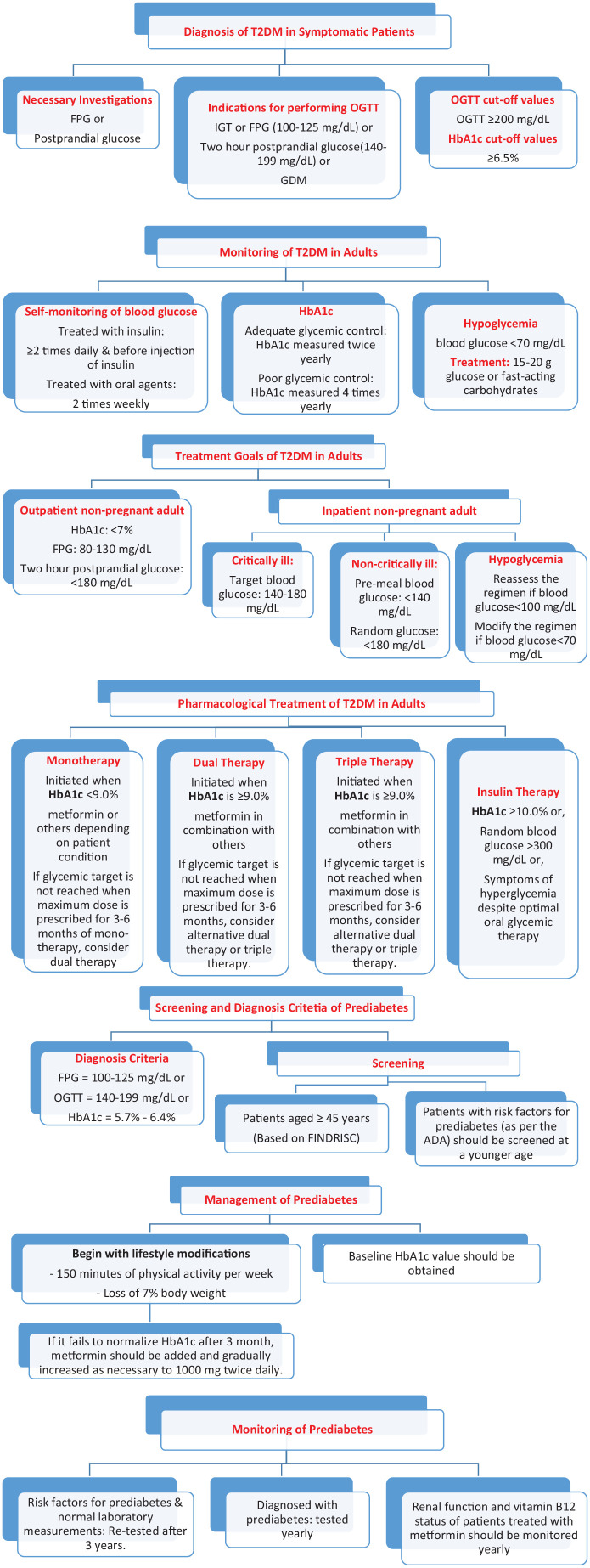

The expert panel agreed that further screening for diabetes and pre-diabetes should be done across the various regions of Iraq. The expert panel noted that the “Finnish Diabetes Risk Score” (FINDRISC) is an appropriate screening tool for T2DM and advised to be translated to Arabic and to be made available to all asymptomatic patients across Iraq. Diagnosis modalities of T2DM is an important matter that the panel wished to address through clear and simple practice recommendations in order to support new physicians, family medicine doctors, and other medical specialists in diabetes management. They highlighted the importance of conducting detailed steps of a comprehensive medical evaluation at the initial visit. They agreed on key elements of diagnostic investigations and criteria, glycemic targets in the outpatient and in-patient settings, in addition to glycemic control monitoring; all of these elements are summarized in Table 1 below and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Iraqi consensus on the diagnosis of T2DM in symptomatic patients.

| Necessary investigations | • Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or, • Postprandial glucose • Renal function test |

| Indications for performing OGTT | • Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or, • FPG (100-125 mg/dL) (5.5-6.93 mmol/L) or, • Two-hour postprandial glucose ([140-199] mg/dL [7.7-11 mmol/L]) or, • Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) |

| OGTT cut-off values | • Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ⩾ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), This test ought to be performed after 2 hours of taking 75 g oral glucose load in the morning post at least 8 hours of overnight fasting |

| HbA1c cut-off values | • ⩾6.5% (48 mmol/mol) |

Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 1.

Iraqi Algorithm for Types 2 Diabetes and Prediabetes Screening and Management

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the diagnosis criteria of T2DM are as follow:8

“FPG ⩾ 126 mg/dL (6.99 mmol/L).” Fasting is described as no energy intake for 8 h or more.

“Two-hour plasma glucose ⩾ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) during an OGTT.” This test needs to be done after a glucose load of 75 g anhydrous glucose dissolved in water.

“HbA1c ⩾ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol).” The Lab performing the test should be National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) certified and standardized to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) assay.

“Random plasma glucose ⩾ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L).” In symptomatic patient

In the first three options, the test needs to be repeated on two separate occasions to verify diagnosis.

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is often used for the T2DM diagnosis in Iraq; however, a standardized method should be applied while doing this test. In Iraq, no standardization of HbA1c assay exists in laboratories; thus, the variability in results. Therefore, the expert panel privileged the use of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and postprandial glucose for the diagnosis of T2DM. They recommended both tests to be repeated in two different days and the use of venous plasma for blood glucose measurement.

Alternatively, serum could be used for blood glucose test; however, it should be noted that the glucose serum value could be approximately 5 mg/dL(0.2 mmol/L) lower than plasma when compared.21 The expert panel endorsed the use of fluoride-containing tubes to reduce glycolysis and insisted on their availability in all settings.22

HbA1c level in some patient may not be directly correlated with blood glucose, thus this should be taken into consideration when using HbA1c to diagnose T2DM.23 Certain conditions can affect the HbA1c level in blood;24 these conditions could range from anemia, asplenia, uremia, severe hypertriglyceridemia or hyperbilirubinemia, chronic salicylate or opioid or vitamin E or C ingestion, splenomegaly, pregnancy and other conditions.25 Thus, in these conditions blood glucose levels should be evaluated for T2DM diagnosis.

Consensus Recommendations for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults

A substantial difference exists in the management of patients with T2DM between Iraqi public and private sectors; this variability is due to treatment access discrepancy.26 Given the challenges encountered in primary care, specialists in tertiary centers and private clinics usually undertake the whole responsibility of educating patients about the disease. They tend to provide nutrition counseling and lifestyle modifications since the number of dieticians available and their role in diabetes management are restricted.27 When specialized care is needed, patients should be referred to the appropriate specialists and multidisciplinary teams usually available in diabetes centers.

In Iraq, recommended laboratory investigations such as HbA1c, lipid profile, and urinalysis are easily accessible to all patients but other clinical care diagnosis and delivery are inconsistent (eg, foot examination); therefore, patient education is crucial and needs an implementable long-term strategy.

Despite the numerous challenges of the healthcare system in Iraq, optimal glycemic control should be the aim of practitioners and patients. Therefore, the experts’ panel developed strict treatment targets to help practitioners and patients to reach the best outcomes in regard to diabetes control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Iraqi consensus recommendations on monitoring and treatment goals of T2DM in adults.

| Glucose monitoring | • Blood glucose self-monitoring • Patients treated with insulin: ⩾ 2 times daily and before injection of insulin • Patients treated with oral agents: 2 times weekly (more frequently if poorly controlled or upon revision of therapy) • HbA1c • In patients with adequate glycemic control, HbA1c should be measured twice yearly • In patients with poor glycemic control, HbA1c should be measured 4 times yearly (more frequently if medication is adjusted) |

| Treatment goals | • Out-patient non-pregnant adult • HbA1c: < 7% (53 mmol/mol) • FPG: 80-130 mg/dL (4.4-7.2 mmol/L) • Postprandial glucose (after 2 hours): < 180 mg/dL (9.9 mmol/L) • Inpatient non-pregnant adult28,29 • Intensive care unit critically ill patients • Target blood glucose: 140-180 mg/dL (7.7-9.9 mmol/L) • Insulin intravenous desired • Non-critically ill patients • Blood glucose (before meal): < 140 mg/dL (7.7 mmol/L) • Postprandial glucose (after 2 hours): < 180 mg/dL (9.9 mmol/L) • Scheduled subcutaneous insulin preferred • Sliding-scale insulin discouraged • Hypoglycemia • Reassess the treatment when blood glucose level < 100 mg/dL (5.5 mmol/L) • Modify the treatment when blood glucose level < 70 mg/dL (3.8 mmol/L) |

| Hypoglycemia | • Random blood sugar < 70 mg/dL (3.8 mmol/L) • Treatment: 15-20 g glucose or fast-acting carbohydrates that contain glucose. If the patient is unable to swallow or is unresponsive, subcutaneous or intramuscular glucagon or intravenous glucose should be given by a trained family member or medical personnel. • Repeated hypoglycemic episodes should prompt clinician to evaluate treatment regimen. |

Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

All agreed that glycemic target for patients with T2DM can be individualized based on

Age;

Disease duration;

Psycho-socioeconomic considerations;

Hypoglycemia risk;

Vascular complications;

Other comorbidities.

Lifestyle management

Eating healthy, exercising regularly, quitting smoking and maintaining a healthy weight are all component of a healthy lifestyle which is essential for diabetes control.30 Physicians and health authorities should invest in programs that support patients with diabetes mellitus in implementing lifestyle modifications.

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus should be involved in exercise program diabetes in 2 to 3 sessions/week (150 min) of resistance exercise on nonconsecutive days. Exercise program improve glucose control, reduce insulin resistance and improve wellbeing.

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) trial showed that a decrease by 58% in the cumulative incidence of diabetes with lifestyle medications versus placebo. However, patients treated with metformin showed risk reduction by 31%.31-33 Due to the lack of infrastructure, social and religious constraints, strict lifestyle changes similar to the DPP trial may be not achievable for most patients in Iraq; traditional nutritional advice about weight loss and sugar restriction also proved to be inadequate. Intensive medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is an effective approach to lifestyle management and is the cornerstone of diabetes management and prevention of its complications. Nutritional recommendations should take in account the individual’s knowledge of nutrition, willingness to change eating habits, and barriers to change in addition to personal and cultural preferences.

This could be achieved through intensive nutrition counseling during the first 6 months that follow the initial diagnosis and annual follow-up thereafter. MNT can help patients normalize their blood glucose, lipid profile, and blood pressure. It takes into account individual and cultural preferences and is evidence-based.34

In the ADA 2017 guidelines, the following goals were presented for an effective MNT:35

Endorse a healthy lifestyle and a good eating pattern to reach and maintain body weight goals.

Achieve individualized goals of glucose level, blood pressure and lipids.

Promote behavioral change to achieve goals and overcome barriers

Provide a comprehensive, practical and, if possible, pleasurable diet plan rather than to focus on individual nutrients.

The dietary recommendations were as follows:

Carbohydrate intake from whole grains, vegetables, and others, especially foods high in fiber and low in glycemic load.

Control sugar-sweetened beverages for patients with diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease (CVD) patient and to reduce weight.

Mediterranean, DASH, and plant-based diets could be good choices.

Proteins: In individuals with T2DM, carbohydrate sources high in proteins are preferable not to be used.

Dietary fat: a Mediterranean-style diet rich in monounsaturated fats may improve glucose metabolism. Eating foods including long-chain ω-3 fatty acids (fatty fish, nuts. . .) may be beneficial for CVD; ω-3 dietary supplementation is not supported by studies.

Sodium: sodium ingestion needs to be limited to less than 2300 mg/day, additional restriction might be indicated for patients with DM, hypertension (HTN) and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Nonnutritive sweeteners

Consumption of nonnutritive sweeteners decrease overall energy intake when it substitutes caloric sweeteners; however, people are encouraged to reduce both and to drink more water.23 According to Iraqi experts, the socio-economic status of patients treated in the private sector permits them more to attain their lifestyle modifications goals. Unfortunately, MNT is only sporadically implemented in Iraq due to the limited number of dieticians and dietary modifications are challenging due to food availability and limited financial resources.

Pharmacological management

Although a healthy lifestyle is the cornerstone of diabetes management but after a certain period time medication (monotherapy or combination) may be needed in addition to lifestyle modifications to normalize blood glucose levels; the following Table 3 lists the available treatment in Iraq:

Table 3.

Diabetic medications available in Iraq.

| Public sector (eg, hospitals, diabetic centers) | Private sector |

|---|---|

| First line: metformin Second line: sulfonylureas (SUs)—glibenclamide Third line: insulin |

First line: metformin Second line: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i) SUs, thiazolidinedione-(TZD)—pioglitazone, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 Inhibitors (SGLT2i)—dapagliflozin, empagliflozin and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist—(GLP-1RA)—liraglutide Third line: insulin |

Abbreviations: DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; SUs, sulfonylureas; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Patients with T2DM may need insulin injections in case the disease was not controlled with an oral medication.36 Nevertheless, pharmacological treatment should always be combined with lifestyle modifications.37 According to the experts’ opinion and experience, approximately 70% of the patients with T2DM in Iraq are treated with oral therapy and 30% with injectable medications. It should be noted that dual/combination therapies either oral or injectable are largely superior to monotherapy. Factors that must be considered when selecting a pharmacological treatment option for patients with T2DM include38

Efficacy of the medication;

Durability of anti-hyperglycemic effect;

Risk of hypoglycemia associated with the medication;

Potential cardiovascular benefit;

Patient’s weight;

Cost and ease of administration;

Other comorbid conditions (eg, chronic kidney disease).

The expert panel agreed that the preferred treatment for T2DM in Iraq takes into consideration several factors as follows:

Glycemic control;

Patient preferences;

Available therapies.

It should be noted that the treatment choices is not limited to the above factors.

Monotherapy

According to the ADA guidelines,23 monotherapy should be initiated if HbA1c is < 9.0% (75 mmol/mol). Monotherapy treatment options in Iraq include metformin, SUs, TZD, DPP-4i and GLP-1RA. Sometimes an initial combination therapy could be considered since the absolute effectiveness of most oral medications rarely exceeds 1%.

Metformin is the medication of choice in monotherapy because of its high efficacy (up to 2% HbA1c reduction), low risk of hypoglycemia, and low cardiac toxicity.39 However, a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 30 mL/min is a contraindication for metformin.40 The ADA,41 “American association of clinical endocrinologists/American college of endocrinologist (AACE/ACE)”42 and IDF guidelines10 established metformin as the medication of choice at all stages of diabetes management. A recent draft of the joint consensus statement from the ADA and the EASD on the management of hyperglycemia in T2DM reaffirmed metformin combined with comprehensive lifestyle management as the foundational therapy of T2DM.9

The expert panel agreed that patient diagnosed with T2DM should start metformin immediate release at a dose of 500 to 1000 mg/day gradually titrated to 2000 mg/day, unless contraindicated along with lifestyle therapy. The maximum dose of metformin immediate release that can be prescribed is 3000 mg/day.

Metformin extended release (XR) is recommended to improve patient compliance or in patients who develop side effects on the immediate-release formulation. The maximum dose of metformin should be continued at least for 3 months before adding another medication.41 Metformin can be used and is well tolerated as a combination therapy with other oral therapies or with insulin. Table 4 below summarizes the steps in metformin prescription, its initial dose, titration and maximal dose in both release forms.

Table 4.

Metformin prescription steps in first line.

| Metformin | ||

|---|---|---|

| Form | Immediate release | Extended release |

| Initial dose | 500-1000 mg/day | 500 mg/day |

| Titration | 500 mg every 10-15 day | 500 mg every 10-15 day |

| Optimum dose | 2000 mg/day There is evidence that 3000 mg/day may have extra benefit |

2000 mg/day |

SUs are still the most used anti-diabetic agents in Iraq. This is maybe due to their lower cost, to the possibility of once-a-day dosing and to the presence of an association with metformin in the same tablet. Their main effect is to increase plasma insulin concentrations.

To minimize the risk of hypoglycemia that might be associated with SUs, several factors should be considered prior to prescribing this class of pharmacological agents mainly:

Patient aged < 65 years;

Normal renal and hepatic functions;

No diagnosis of hypothyroidism or Addison disease

Some SUs combinations have different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics properties than the plain SUs.

Dual therapy

Dual therapy ought to be started when HbA1c is ⩾ 9.0% (75 mmol/mol) or on failure to control blood glucose level after 3 months of maximum dose of monotherapy. Metformin is the monotherapy drug of choice in Iraq and is usually combined with SUs or DPP-4i; as per the expert’s opinion, dual therapy treatment options that can be considered as add-on to metformin are as follows:

Sus

Meglitinides

DPP-4i

TZD

GLP-1RA

SGLT2i

Insulin

Fixed-dose combinations (FDC) are generally recommended in dual therapy especially metformin and SUs since they have a favorable pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetic over other free combination. Available studies support the wider use of FDC in the treatment of T2DM patients and the efficacy and safety of newer FDC seems to be promising and adds more treatment options.43,44

The panel highlighted that, when prescribing and choosing the dual therapy option, the physician should consider drug-specific effect and patient factors. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular patients should take in combination to diabetic therapy a medication shown to reduce cardiovascular risks, two different SUs should not be combined, DPP-4i should not be combined with GLP-1RA and the insulin secretagogues such as SUs and meglitinides should be discontinued once insulin is introduced into a treatment regimen or at least within few months. To minimize the risk of hypoglycemia that might be associated with SUs combinations, take into consideration the same factors mentioned in the previous section for SUs. In dual therapy, some FDC of SUs and metformin have a favorable pharmacodynamics/pharmacokinetics over the free combination.

Insulin resistance results from a low insulin cellular response, low-insulin-dependent glucose levels and low hepatic insulin sensitivity. Clinical studies showed that pioglitazone enhances insulin sensitivity by improving all these parameters. Subsequently, the decrease in insulin resistance due to pioglitazone in patients with T2DM contributes in lowering plasma glucose, insulin concentrations and HbA1c values.

It is demonstrated that pioglitazone has a cumulative impact on glycemic control when combined to SUs, metformin, or insulin. Despite its benefits, pioglitazone may increase the risk of bladder cancer.45

The “Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus” (SAVOR)” “Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 53” trial was done in 2013 in the aim to evaluate the cardiovascular safety and efficacy of saxagliptin in patients with diabetes mellitus with cardiovascular risk factors. It showed that despite the fact that saxagliptin controls diabetes very well and decreases and prevents microalbuminuria; heart failure and hypoglycemia cases were reported. Therefore, patients with a history of heart failure and CVD should use this medication with care.46

Triple therapy

Triple therapy should be considered after 3 months in patients who are not well controlled on dual therapy. Drug-specific effect and patient factors should be considered.

Insulin therapy

In newly diagnosed and currently treated patients, insulin therapy with metformin and intense lifestyle modifications should be considered in those when:

HbA1c ⩾ 10.0% (86 mmol/mol);

Random blood glucose ⩾ 300 mg/dL (16 mmol/L);

Presence of hyperglycemia symptoms and evidence of catabolism (weight loss).

The dose of insulin should be divided equally into basal and bolus. Insulin therapy may be initiated with basal insulin at a dose of 0.2 U/kg before bed then the dose may be adjusted by 3 U every 3 days to achieve the target FPG, or as bolus insulin with a dose of 5 U and increase the dose by 2 U until the target 2 hour postprandial glucose is achieved or as replacement, with a standard total daily dose (TDD) of basal-bolus regimen of 0.5 U/kg.

Augmentation therapy may contain basal or bolus insulin as basal-bolus insulin and correction or premixed insulin constitutes replacement therapy.47 The dose of insulin can be reduced by 4 U in case of hypoglycemia.

If the maximum bedtime basal insulin dose of 30 U is reached without achieving target FPG, the total dose of basal insulin required should be divided into two doses, one dose administered in the morning and one dose administered at night. If HbA1c value didn’t reach normal levels, consider insulin intensification by adding one bolus insulin before the main meal (basal plus 1) then two bolus insulin (basal plus 2) before reaching the full basal-bolus regimen (one or two basal, with three bolus insulin before each meal).48 For patients who prefer fewer injections per day, premixed insulin could be attempted with the same TDD, where 60% is taken before breakfast and 40% before dinner(premixed insulin available in Iraq includes NPH/regular 70/30, Lispro 50/50, Lispro 75/25 and Aspart 70/30).49 The Table 5 and Figure 1 here below summarizes the Iraqi Consensus Recommendations on Pharmacological Treatment of T2DM in Adults, and the Table 6 summarizes the recommended insulin regimens.

Table 5.

Iraqi consensus recommendations on pharmacological treatment of T2DM in adults.

| Monotherapy | Initiated when HbA1c is < 9.0% (75 mmol/mol)23

Monotherapy: metformin or metformin XRa or the following depending on patient condition • SUs • Meglitinides • TZD • DPP-4i • SGLT2i • GLP-1RA • Consider drug intensification to help achieve glycemic control • If glycemic target is not reached when maximum dose is prescribed for 3-6 months of mono-therapy, consider dual therapy |

|||||

| Dual therapy | Initiated when HbA1c is ⩾ 9.0% (75 mmol/mol) Dual therapy: metformin in combination (FDC preferred) with: • SUs • Meglitinides • TZD • DPP-4i • SGLT2i • GLP-1RA • Insulin basal If glycemic target is not reached when maximum dose is prescribed for 3-6 months, consider alternative dual therapy or triple therapy. |

|||||

| Triple therapy | Metformin in combination with | |||||

| SUs + TZD Or DPP-4i Or SGLT2i Or GLP-1RA Or Insulin |

TZD + SUs Or DPP-4i Or SGLT2i Or GLP-1RA Or Insulin |

DPP-4i + SUs Or TZD Or SGLT2i Or Insulin |

SGLT2i + SUs Or TZD Or DPP-4i Or GLP-1RA Or Insulin |

GLP-1RA + SUs Or TZD Or SGLT2i Or Insulin |

Insulin (Basal) + TZD Or DPP-4i Or SGLT2i Or GLP-1-RA |

|

| Insulin therapy | Considered in patients with: • HbA1c ⩾ 10.0% (86 mmol/mol) or, • Random blood glucose > 300 mg/dL or, • Symptoms of hyperglycemia despite optimal oral glycemic therapy |

|||||

Abbreviations: FDC, fixed dose combination; DPP-4i, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor; GLP-1RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors; SUs, sulfonylureas; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TZD, thiazolidinedione; XR, extended release.

Metformin extended release (XR) can be considered to improve patient compliance or in patients who develop side effects on the immediate release formulation.

Table 6.

Iraqi consensus recommendations on insulin regimens.

| Type of regimen | Dosing | Adjustments |

|---|---|---|

| Basal insulin | 0.2 U/kg/daily at bed time | • If target FPG not reached • add 3 U/every 3 days • If maximum bedtime 30U dose reached divide into 2 doses: 1 morning and 1 evening; if target not reached add bolus before main meals 1 then 2 then 3. • If hypoglycemia reduce by 4U |

| Bolus | 5U/daily | 2U till target FPG reached: TDD 0.5U/kg |

| Premixed | Same TDD 60% before breakfast & 40% before dinner |

Abbreviations: FPG, fasting plasma glucose; TDD, total daily dose.

Ramadan

During Ramadan, fasting is a very important obligation for many Muslims, even if they are not obliged to fast due to some health issues. Blood glucose levels can be affected during fasting, it may cause severe hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.50 Patients with diabetes are affected differently during Ramadan due to several factors such as diabetes type, medications, presence of comorbidities and complications, work conditions, social status and prior experience.51 For those who seek exemption, HbA1c should be well controlled at least 3 months before Ramadan and patients should be educated about Ramadan fasting. Exceptionally, metformin treatment allows patients to fast without dose modification because of the minimal risk of hypoglycemia. Patients should take extended-release formulations of metformin with the sunset meal (once daily).52 For patients treated with once daily SUs, it can be taken with Iftar. Those on twice daily SUs may reduce the dose taken with Suhoor by half.53 Patients treated with DPP-4i, GLP-1RA, SGLT2i, and TZDs do not require dose adjustment while patients on basal insulin may reduce the dose by 30% and take it with Iftar.54

Patients on twice-daily basal or premixed insulin may reduce the Suhoor dose by 50% and those on basal-bolus insulin therapy should be encouraged not to fast. If these patients insist on fasting, their glucose should be well controlled at least 3 months prior to Ramadan.

It should be noted that the usual breakfast bolus dose may be taken before Iftar, half of the dinner dose should be taken before Suhoor, and the lunch dose should be omitted.55

Prediabetes

Prediabetes, as defined by the ADA, is a condition characterized by glycemic parameters above normal but below diabetes threshold.23 Diagnosis criteria, screening, management and monitoring are summarized in Table 7 and Figure 1 below.

Table 7.

Iraqi consensus recommendations on prediabetes.

| Diagnosis criteria | • FPG = 100-125 mg/dL (5.5-6.93 mmol/L) or, • OGTT = 140-199 mg/dL (7.7-11 mmol/L) or, • HbA1c = 5.7%-6.4% (39 mmol/mol-46 mmol/mol) |

| Screening | • Patients aged ⩾ 45 years who visit clinic or a hospital in Iraq should be systematically screened for prediabetes using the FINDRISC as precursor to laboratory measurement (FPG for confirmation). • Patients with risk factors for prediabetes23 should be screened opportunistically at a younger age; the risk factors are as follow: • “HbA1c ⩾ 5.7% (39 mmol/mol), IGT, or IFG on previous testing” • “First-degree relative with diabetes” • Women who were diagnosed with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus • “CVD history” • “Hypertension (⩾140/90 mmHg or on therapy for hypertension)” • “HDL cholesterol level < 35 mg/dL (0.90 mmol/L) and/or a triglyceride level > 250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L)” • “Women with polycystic ovary syndrome” • “Physical inactivity” • “Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance (eg, severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans)” • Metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), macrosomia, chronic glucocorticoid exposure, atypical antipsychotic therapy use |

| Management | • Baseline creatinine with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and HbA1c value should be obtained. • Management of prediabetes should begin with lifestyle modifications. • Lifestyle change programs should encourage 150 minutes of physical activity per week and loss of 7% body weight. • After 3 months, if lifestyle therapy fails to normalize HbA1c or if HbA1c value approaches 6.5%, metformin immediate release should be added and gradually increased as necessary to 1000 mg twice daily. • Metformin can be added in patients with IFG and/or IGT who also have additional risk factors. • Metformin extended release (XR) is recommended to improve patient compliance or in patients who develop side effects on the immediate release formulation. |

| Monitoring | • Patients with risk factors for prediabetes and normal laboratory measurements should be re-tested after 3 years. • Patients diagnosed with prediabetes should be tested yearly. • Renal function and vitamin B12 status of patients treated with metformin should be monitored yearly56 • In Iraq, laboratory tests to assess B12 status are not standardized. • Particular attention should be given to patients who are vegetarian and those who present with peripheral neuropathy. • Regarding treatment goals of outpatient non-pregnant T2DM, glucose targets should be individualized and take into account life expectancy, disease duration, presence or absence of micro- and macrovascular complications, CVD risk factors, comorbid conditions, and risk for hypoglycemia, as well as the patient’s psychological status. |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; FINDRISC, Finnish Diabetes Risk Score; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; XR, extended release.

Patients aged 45 years and above, overweight or obese, and with risk factors including, but not limited to, first-degree relative with diabetes, history of CVD, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, should be screened for prediabetes.57 Ideally, screening for prediabetes can be done using the FINDRISC questionnaire.58 If a questionnaire is not available, fasting blood glucose should be used. Patients with prediabetes should be tested yearly. The tests should be done every 3 years in case of normal values.59

Management of prediabetes can be achieved through lifestyle interventions, pharmacotherapy, and control of risk factors.60 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved yet any medication for the management of prediabetes, but evidence base data suggest that metformin is the safest long-term drug to prevent diabetes.61

In addition, thiazolidinediones and GLP-1RA may prevent the conversion to diabetes by as much as 60%–70% but patients report frequent side effects from these classes of medication.62 Alternatively, metformin can achieve a 25% to 30% reduction in conversion with less side effects.63

Discussion and Conclusion

Iraq has gone through an excruciating and painful process to reach the point where it is today. Multiple factors, including wars, sectarian conflicts, politics, financial matter, and security situation, had a lasting effect on healthcare system. This has led to a lack of expertise, medical equipment, supplies and drugs.

RCT and epidemiological studies could provide the necessary data to support the development of country-specific clinical practice guidelines. For undiagnosed diabetes patents, educational programs and social media platforms should be used to raise awareness about diabetes and impaired fasting glucose (IFG). Ready-to-use population-specific (eg, nutrition for weight reduction; nutrition in CKD) educational cards should be developed to assist healthcare practitioners with nutritional advice. Brief informative videos could be recorded and displayed on social media or in clinic and hospital waiting rooms. According to experts, more resources should be invested to properly manage patients with diabetes mellitus.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was financially supported by Merck KGaA Middle East Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Author Murad Al-Naqshbandi was employed by company Merck KGaA Middle East Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Merck KGaA was only involved in funding the logistical arrangement for the meeting, the authors declare that this study received no funding from any party.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: The experiments were conceived and designed by MA, MA, HAN, HAA, MAA, AA, BAM performed the experiments. MS analyzed and interpreted the data. AAK contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. SA-I., AA-K, HA-R, T, A.A., H.H., M.S., M.A.-N., A.M wrote the paper.

ORCID iDs: Haider Ayad Alidrisi  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3132-1758

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3132-1758

Majid Al-Abbood  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2625-8013

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2625-8013

Abbas Mansour  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8083-6024

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8083-6024

References

- 1. Chen C, Cohrs CM, Stertmann J, Bozsak R, Speier S. Human beta cell mass and function in diabetes: recent advances in knowledge and technologies to understand disease pathogenesis. Mol Metab. 2017;6:943-957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerich JE. Contributions of insulin-resistance and insulin-secretory defects to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:447-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Updated October 30, 2018. Accessed March, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Informed Health.org. Type 2 Diabetes: Overview. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279509/. Updated January 11, 2018. Accessed March, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hu FB. Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1249-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Diabetes Federation. Chapter 3. The global picture. In: Diabetes Atlas. 8th ed Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2017. https://idf.org/e-library/epidemiology-research/diabetes-atlas/134-idf-diabetes-atlas-8th-edition.html. Accessed March, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mansour AA, Al-Maliky AA, Kasem B, Jabar A, Mosbeh KA. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in adults aged 19 years and older in Basrah, Iraq. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:139-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. American Diabetes Association. 2 classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:S14-S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2018;41:2669-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Clinical Practice Recommendations for Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2017. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwj_sZvRitjlAhUBXxoKHXimDrUQFjAAegQIBBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.idf.org%2Fcomponent%2Fattachments%2Fattachments.html%3Fid%3D1270%26task%3Ddownload&usg=AOvVaw2o-Kymowd4Kx910Ewyw_Ar. Updated 2017. Accessed March, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Non-Communicable Diseases–Iraq. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO EMRO; 2019. http://www.emro.who.int/pdf/irq/programmes/non-communicable-diseases-ncds.pdf?ua=1. Updated November 7, 2019. Accessed March, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Health in Iraq–The Current Situation, Our Vision for the Future and Areas of Work. Baghdad, Iraq: Iraq Ministry of Health; 2004. https://www.who.int/hac/crises/irq/background/Iraq_Health_in_Iraq_second_edition.pdf. Updated December, 2004. Accessed March, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haleem AA, Al-Rabaty AA. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among school age children in Kurdistan region/IRAQ. J Nutr Disord Ther. 2016;6 https://www.longdom.org/conference-abstracts-files/2161-0509.C1.004-009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lafta RK, Kadhim MJ. Childhood obesity in Iraq: prevalence and possible risk factors. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:389-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American Bar Association. The status of women in Iraq: an assessment of Iraq’s De Jure and De Facto compliance with international legal standards. http://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/hr_statusofwomeniniraq_aba_july2005_0.pdf. Published July, 2005.

- 16. Idris I. K4D Helpdesk Report: Inclusive and Sustained Growth in Iraq. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies; 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b6d747440f0b640b095e76f/Inclusive_and_sustained_growth_in_Iraq.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faihan SM. Urban policy in Iraq for the period 1970-2012, evaluation study. J Adv Soc Res. 2014;4:58-76. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Musaiger AO, Al-Mufty BA, Al-Hazzaa HM. Eating habits, inactivity, and sedentary behaviour among adolescents in Iraq: sex differences in the hidden risks of non-communicable diseases. Food Nutr Bull. 2014;35:12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Al-Hilfi TK, Lafta R, Burnham G. Health services in Iraq. Lancet. 2013;381:939-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mikhael EM, Hassali MA, Hussain SA, Shawky N. Self-management knowledge and practice of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Baghdad, Iraq: a qualitative study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;12:1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frank EA, Shubha MC, D’Souza CJ. Blood glucose determination: plasma or serum? J Clin Lab Anal. 2012;26:317-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peake MJ, Bruns DE, Sacks DB, Horvath AR. It’s time for a better blood collection tube to improve the reliability of glucose results. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S13-S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shepard JG, Airee A, Dake AW, McFarlands MS, Vora A. Limitations of A1c interpretation. South Med J. 2015;108:724-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Radin MS. Pitfalls in hemoglobin A1c measurement: when results may be misleading. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:388-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mansour AA, Alibrahim NTY, Alidrisi HA, et al. Prevalence and correlation of glycemic control achievement in patients with type 2 diabetes in Iraq: a retrospective analysis of a tertiary care database over a 9-year period. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mansour AA. Patients’ opinion on the barriers to diabetes control in areas of conflicts: the Iraqi example. Confl Health. 2008;2:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, Dinardo M, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1119-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:16-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aschner P. New IDF clinical practice recommendations for managing type 2 diabetes in primary care. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;132:169-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. 10-year follow up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677-1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow up: the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:866-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. American Diabetes Association. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:S61-S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American Diabetes Association. Lifestyle management. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:S33-S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chaudhury A, Duvoor C, Reddy Dendi VS, et al. Clinical review of antidiabetic drugs: implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus management. Front Endocrinol. 2017;8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Centis E, Marzocchi R, El Ghoch M, Marchesini G. Lifestyle modification in the management of the metabolic syndrome: achievements and challenges. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:373-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cavaiola TS, Pettus JH. Management of type 2 diabetes: selecting amongst available pharmacological agents. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al. , eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rhee SY, Kim HJ, Ko SH, et al. Monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Korean J Intern Med. 2017;32:959-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Heaf J. Metformin in chronic kidney disease: time for a rethink. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34:353-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;40:S73-S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2017 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:207-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blonde L, Montanya E. Comparison of liraglutide versus other incretin-related anti-hyperglycaemic agents. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:20-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vijayakumar TM, Jayram J, Meghana Cheekireddy V, Himaja D, Dharma Teja Y, Narayanasamy D. Safety, efficacy, and bioavailability of fixed-dose combination in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic updated review. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2017;84:4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lewis JD, Habel LA, Quesenberry CP, et al. Pioglitazone use and risk of bladder cancer and other common cancers in persons with diabetes. JAMA. 2015;314:265-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1317-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Petznick A. Insulin management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:183-190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davidson MB. Insulin therapy: a personal approach. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33:123-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Walsh J, Roberts R, Bailey T. Guidelines for optimal bolus calculator settings in adults. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5:129-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahmad J, Pathan MF, Jaleel MA, et al. Diabetic emergencies including hypoglycemia during Ramadan. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:512-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Al-Arouj M, Assaad-Khalil S, Buse J, et al. Recommendations for management of diabetes during Ramadan: update 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1895-1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Niazi AK, Kalra S. Patient centred care in diabetology: an Islamic perspective from South Asia. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2012;11:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beshyah SA, Benbarka MM, Sherif IH. Practical management of diabetes during Ramadan fast. Libyan J Med. 2007;2:185-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hassanein M, Al-Arouj M, Hamdy O, et al. Diabetes and Ramadan: practical guidelines. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;126:303-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Candido R, Wyne K, Romoli E. A review of basal-bolus therapy using insulin glargine and insulin lispro in the management of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:927-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aroda VR, Knowler WC, Crandall JP, et al. Metformin for diabetes prevention: insights gained from the diabetes prevention program/diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Diabetologia. 2017;60:1601-1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology: clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:1-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang Y, Hu G, Zhang L, Mayo R, Chen L. A novel testing model for opportunistic screening of pre-diabetes and diabetes among U.S. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S81-S90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kanat M, De Fronzo RA, Abdul-Ghani MA. Treatment of prediabetes. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1207-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sherwin RS, Anderson RM, Buse JB, et al. Prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:s47-s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Soccio RE, Chen ER, Lazar MA. Thiazolidinediones and the promise of insulin sensitization in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2014;20:573-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nathan DM, Davidson MB, Defronzo RA, et al. Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:753-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]