To date, the major host organisms used for the heterologous production of terpenoids, i.e., E. coli and S. cerevisiae, do not have high-flux isoprenoid pathways and involve tedious metabolic engineering to increase the precursor pool. Since carotenoid-producing bacteria carry endogenous high-flux isoprenoid pathways, we used a carotenoid-producing mutant of A. brasilense as a host to show its suitability for the heterologous production of geraniol and amorphadiene as a proof-of-concept. The advantages of using A. brasilense as a model system include (i) dispensability of carotenoids and (ii) the possibility of overproducing carotenoids through a single mutation to exploit high carbon flux for terpenoid production.

KEYWORDS: metabolic engineering, geraniol, amorphadiene, carotenoids, A. brasilense

ABSTRACT

Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been used extensively for heterologous production of a variety of secondary metabolites. Neither has an endogenous high-flux isoprenoid pathway, required for the production of terpenoids. Azospirillum brasilense, a nonphotosynthetic GRAS (generally recognized as safe) bacterium, produces carotenoids in the presence of light. The carotenoid production increases multifold upon inactivating a gene encoding an anti-sigma factor (ChrR1). We used this A. brasilense mutant (Car-1) as a host for the heterologous production of two high-value phytochemicals, geraniol and amorphadiene. Cloned genes (crtE1 and crtE2) of A. brasilense encoding native geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthases (GGPPS), when overexpressed and purified, did not produce geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) in vitro. Therefore, we cloned codon-optimized copies of the Catharanthus roseus genes encoding GPP synthase (GPPS) and geraniol synthase (GES) to show the endogenous intermediates of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in the Car-1 strain were utilized for the heterologous production of geraniol in A. brasilense. Similarly, cloning and expression of a codon-optimized copy of the amorphadiene synthase (ads) gene from Artemisia annua also led to the heterologous production of amorphadiene in Car-1. Geraniol or amorphadiene content was estimated using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and GC. These results demonstrate that Car-1 is a promising host for metabolic engineering, as the naturally available endogenous pool of the intermediates of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway of A. brasilense can be effectively utilized for the heterologous production of high-value phytochemicals.

IMPORTANCE To date, the major host organisms used for the heterologous production of terpenoids, i.e., E. coli and S. cerevisiae, do not have high-flux isoprenoid pathways and involve tedious metabolic engineering to increase the precursor pool. Since carotenoid-producing bacteria carry endogenous high-flux isoprenoid pathways, we used a carotenoid-producing mutant of A. brasilense as a host to show its suitability for the heterologous production of geraniol and amorphadiene as a proof-of-concept. The advantages of using A. brasilense as a model system include (i) dispensability of carotenoids and (ii) the possibility of overproducing carotenoids through a single mutation to exploit high carbon flux for terpenoid production.

INTRODUCTION

Mining of chemical diversity of secondary metabolites for therapeutic or societal needs has been of great interest in recent times. Terpenes represent one of the largest and most diverse classes of secondary metabolites (1). The enormous diversity of their structures is responsible for diverse functions, such as photosynthetic pigments (phytol, carotenoids), hormones (gibberellins), electron carriers (ubiquinone, plastoquinone), communication, defense mechanisms, etc. Different terpene derivatives (terpenoids) possess anticancer, antifungal, antimicrobial, antiviral, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, and immunomodulatory properties (2). Monoterpenes (geraniol, limonene, and menthol), sequiterpenes (valencene, humulene, artemisinin, zerumbone, and nootkatone), and diterpenes (paclitaxel and sclareol) are currently in use in therapeutic (artemisinin, zerumbone, paclitaxel, etc.) and flavor/fragrance (menthol, nootkatone, linalool, and sclareol) industries (1). Ever-increasing knowledge about their properties related to health and well-being have continued to increase the demand for them.

Plants are the most frequent natural sources of these secondary metabolites but take relatively longer periods to produce them, and only in small quantities. Their purification from biological material suffers from low yields, impurities, and consumption of large amounts of natural resources (3). Because of their chemical complexity, their complete chemical synthesis is inherently difficult and expensive, and it requires environmentally hazardous catalysts (4). For these reasons, engineering of the metabolic pathways to produce large quantities of terpenoids in a suitable biological host presents an attractive alternative for producing these compounds in a cost-effective manner. The last decade has seen rapid increases in the use of synthetic biological approaches to produce phytochemicals in microorganisms to scale up their production and commercial availability and to create more resilient alternative sources. A large number of natural products, like terpenoids, polyketides, and flavonoids, have been produced using metabolic engineering in microbial hosts (5, 6). Various terpenoids or their precursors, such as taxadiene (7, 8), amorphadiene (9), limonene (10), carvone (10), carveol (10), pinene (11), sabinine (11), and artemisinic acid (12), have been produced in Escherichia coli. Taxadiene (13), artemisinic acid (14), valencene (15), and patchoulol (15) have also been produced in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The metabolic engineering approaches used in E. coli have involved engineering the expression of exogenous mevalonate pathway genes to enhance the availability of precursors, as this bacterium does not possess a high-flux isoprenoid pathway (9).

So far, metabolically engineered strains of E. coli and S. cerevisiae have been the main workhorses for the biotechnological production of a few terpenoids (e.g., artemisinin, paclitaxel) or their precursors (amorphadiene, taxadiene, etc.) (7, 9, 13, 14), but neither possesses the high-flux isoprenoid pathway required for terpenoid production. Hence, tedious metabolic engineering was done in both to increase the flux (9, 14). Carotenoid-producing microorganisms appear to be more promising hosts, as they harbor an intrinsic high-flux isoprenoid pathway that can be channeled toward the production of desired metabolites by engineering of only a few steps. Most of the carotenoid-producing microorganisms are photosynthetic, and carotenoid biosynthesis is essential for harvesting light and quenching reactive oxygen species in these microorganisms (16). Cyanobacteria, because of their carotenoid-producing ability, have been used as a host for the production of terpenoids (17). Some attempts were also made to use photosynthetic carotenoid-producing bacteria as a host for heterologous terpenoid production (18). Since carotenoids are indispensable in these microorganisms, the native carbon flux toward carotenoids pathway cannot be completely exploited for terpenoid biosynthesis. Carotenoid production, however, is not essential for the growth and survival of nonphotosynthetic carotenoid-producing bacteria, which offer an opportunity for almost complete exploitation of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway for heterologous production of terpenoids.

Corynebacterium glutamicum is a nonphotosynthetic, carotenoid-producing bacterium which has been successfully used as a host for the production of valencene and patchoulol (19, 20). The first attempt to produce valencene in this bacterium, by heterologous expression of the (+)-valencene synthase gene from Citrus sinensis, failed due to the small intracellular pool of farnesyl diphosphate (FPP). However, expression of the FPP synthase gene (ispA) from E. coli or ERG20 from S. cerevisiae and the valencene synthase gene from the Nootka cypress plant improved (+)-valencene titers by 10-fold to 2.41 ± 0.26 mg (+)-valencene per liter (19). Systematic metabolic engineering of this bacterium was later done to improve the production of patchoulol by reducing carotenoid formation, increasing precursor supply by overproducing limiting enzymes of the MEP pathway, and heterologous expression of the gene encoding patchoulol synthase (PcPS) from Pogostemon cablin (20). By using such strategies, patchoulol titers could increase to 60 mg per liter.

Azospirillum brasilense, a nonphotosynthetic bacterium, produces low levels of bacterioruberin-type carotenoids (21) under ambient conditions but possesses the ability to produce enhanced levels of carotenoids in the presence of light or other inducing conditions (22). In an earlier study, we had isolated a carotenoid-overproducing mutant (Car-1) of A. brasilense Sp7 by transposon (Tn5) mutagenesis and showed that the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway was regulated by an extracytoplasmic sigma factor (RpoE1) and its cognate anti-sigma factor (ChrR1) (23). Here, we have metabolically engineered Car-1 to produce geraniol and amorphadiene to show that it is a promising host that can be engineered with ease to produce a variety of other terpene derivatives.

RESULTS

Selection of a carotenoid-overproducing strain of A. brasilense.

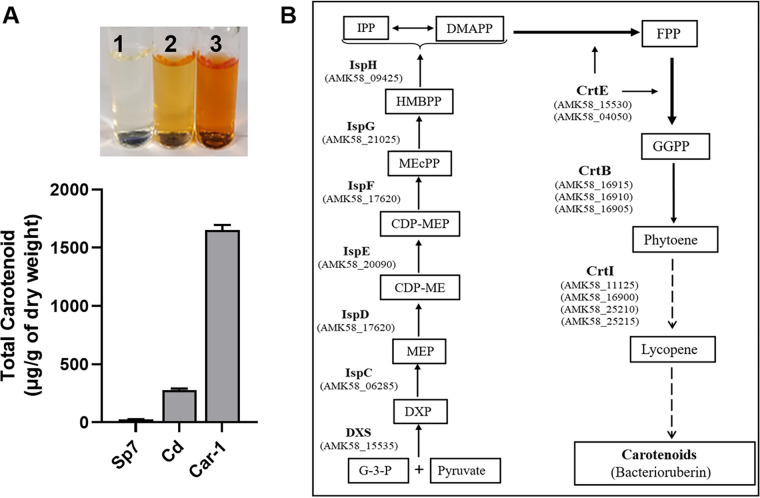

Carotenoid-producing strains of A. brasilense were evaluated for their suitability as hosts for metabolic engineering. Comparison of the carotenoid contents of A. brasilense Cd, a naturally carotenoid-overproducing strain (21), and Car-1, a Tn5 mutant of A. brasilense Sp7 (23), revealed that the latter produced almost 7-fold higher levels of carotenoids (Fig. 1A) than A. brasilense Cd. Since Car-1 produces higher levels of carotenoids (21, 23), it seems to carry an efficient but cryptic carotenoid biosynthetic pathway. We used it as a platform strain for channeling the metabolic intermediates of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway toward heterologous production of plant terpenoids.

FIG 1.

(A) Comparison of carotenoid contents of different A. brasilense strains. The y axis shows total carotenoid (TC) in μg/gram dry weight of the cells. Error bars show the standard deviation from three replicates. Tubes in the inset show the methanol extracts from equal amounts of cells of Sp7 (1), Cd (2), and Car-1 (3) strains. (B) Schematic representation of carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in Azospirillum brasilense. Enzymes involved in different steps of the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) pathway are DXS, deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase; IspC, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase; IspD, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; IspE, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase; IspF, 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidylyltransferase; IspG, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate synthase; and IspH, 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase. This bacterium encodes 2 paralogs of FPP/GGPP synthase (CrtE), 3 paralogs of phytoene synthase (CrtB), and 4 paralogs of phytoene desaturase (CrtI). Intermediates of the pathway are given in enclosed boxes: DXP, d-xylulose-5-phosphate; MEP, 2C-methyl-d-erythritol-4-phosphate; CDP-ME, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol; CDP-MEP, 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol-2-phosphate; MEcPP, 2C-methyl-d-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate; HMBPP, 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate; and GGPP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. Thick arrows indicate the steps that have been established in this bacterium, while the thin arrows indicate the possible steps based on the carotenoid biosynthetic pathways studied in other bacteria. Dotted arrows indicate multistep enzyme pathways.

Analysis of the A. brasilense Sp7 genome for an isoprenoid pathway using the KEGG pathway database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?abf00900) revealed that it possesses all the genes involved in the deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) pathway for the production of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), as well as carotenoids (Fig. 1B). The DXP pathway genes annotated in the A. brasilense Sp7 genome include dxs (AMK58_15535), ispC (AMK58_06285), ispDF (AMK58_17620), ispE (AMK58_20090), ispG (AMK58_21025), and ispH (AMK58_09425). The annotated carotenoid biosynthetic genes include 2 paralogs of crtE (AMK58_15530 and AMK58_04050), 3 paralogs of crtB (AMK58_16915, AMK58_16910, and AMK58_16905), and 4 paralogs of crtI (AMK58_11125, AMK58_16900, AMK58_25210, and AMK58_25215). Since the A. brasilense genome carries multiple paralogs of crt genes, it is not clear whether all the paralogs are functional and, if so, which paralog is more efficient.

Analysis of CrtE1 and CrtE2 enzymatic activity.

We examined whether A. brasilense is able to produce geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and FPP, which are used as substrates for mono- and sesquiterpenoid production, respectively. The terpenoid biosynthetic pathway and the genes of A. brasilense encoding the pathway enzymes are shown in Fig. 1B. Although we have shown earlier the role of two paralogs (CrtE1 and CrtE2) of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS) in the biosynthesis of carotenoids in A. brasilense (24), it is not known if these enzymes release GPP and FPP during synthesis of GGPP from IPP/DMAPP. To examine this, we cloned the genes encoding CrtE1 and CrtE2 in pET28a to construct pET28a-crtE1 (pAK054) and pET28a-crtE2 (pAK055), respectively. The constructs were used for the overexpression of 6×His-tagged CrtE1 and CrtE2, which were purified using Ni-NTA resin. In vitro enzymatic assays carried out individually by providing IPP and DMAPP as the substrates showed the formation of both FPP and GGPP, indicating that both of these enzymes are bifunctional in nature (Fig. 2). These assays, however, did not indicate formation of GPP as an intermediate. This suggests that although CrtE1 and CrtE2 synthesize FPP and GGPP from IPP/DMAPP, they do not seem to produce GPP as an intermediate.

FIG 2.

GC analysis of extracts of CrtE2 and CrtE1 in in vitro enzymatic reactions along with the standards of geraniol and farnesol. The x axis denotes the retention time in minutes and the y axis denotes peak intensity in μV.

Development of a medium-copy-number, broad-host-range expression vector.

We constructed a strong and inducible expression system for A. brasilense by transferring the lacZ promoter (tac-lacUV5) from pMMB206 (25) to pBBR1MCS3 (26), which is a pBBR1 replicon-based, broad-host-range, medium-copy (more than 20 per cell) vector (Tables 1 and 2). For this, lacI and tac-lacUV5 promoters were amplified as one fragment and the t1 and t2 terminators of the E. coli rrnB operon as another fragment from pMMB206. These fragments were inserted into the AseI/XbaI sites of pBBR1MCS3 to construct an expression system (pAK032). The terminator was placed downstream of lacI to stop the transcriptional read-through, which can make the plasmid unstable by transcribing an antisense mRNA of the tetracycline resistance gene located downstream and in the opposite orientation (Fig. 3A). To compare expression efficiencies, we cloned egfp downstream of the lacZ promoter in both the vectors and constructed pMMB206-egfp (pAK024) and pAK032-egfp (pAK040), which were mobilized in A. brasilense, and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) fluorescence of the A. brasilense strains harboring these plasmids was measured. A 2.5-fold higher fluorescence from A. brasilense cells harboring pAK040 than from the cells harboring pAK024 (Fig. 3B) indicated the suitability of pAK032 as a vector for relatively higher expression of genes in A. brasilense.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | (Δlac)U169 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 40 |

| S17-1 | Smr, recA thi pro hsdRM+ RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 λpir | 46 |

| BL21λ(DE3) pLysS | ompT hsdS(rB− mB−) dcm+endA galλ BL21(DE3) | Novagen |

| A. brasilense | ||

| Sp7 | Wild-type strain | 21 |

| Cd | Wild-type carotenoid-producing strain | 21 |

| Car-1 | Carotenoid-producing chrR:Tn5 mutant of A. brasilense Sp7 | 23 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMMB206 | Broad-host-range, low-copy-number lactose-inducible expression vector; Cmr | 25 |

| pBBR1MCS-3 | Broad-host-range, medium-copy-number cloning vector; Tcr | 26 |

| pAK024 | egfp cloned into EcoRI-BamHI sites of pMMB206 | This work |

| pAK032 | pBBR1MCS-3 replicon-based lactose-inducible expression vector; Tcr | This work |

| pAK040 | pBBR1MCS-3 replicon-based lactose-inducible EGFP expressing plasmid; Tcr | This work |

| pAK041 | Codon-optimized A. annua ads cloned into NdeI-PstI sites of pAK032 | This work |

| pAK042 | E. coli ispA cloned into PstI-XhoI sites of pAK041 | This work |

| pAK043 | A. brasilense rpoE1 cloned into XhoI-KpnI sites of pAK042 | This work |

| pAK050 | As pAK042, but ispA replaced with its codon-optimized version | This work |

| pAK051 | As pAK043, but ispA replaced with its codon-optimized version | This work |

| pAK054 | crtE1 cloned into NdeI-HindIII sites of pET28a | This work |

| pAK055 | crtE2 cloned into NdeI-HindIII sites of pET28a | This work |

| pAK056 | Codon-optimized C. roseus gpps cloned into NdeI-XhoI sites of pAK032 | This work |

| pAK057 | Codon-optimized C. roseus ges cloned into NdeI-XhoI sites of pAK032 | This work |

| pAK058 | Codon-optimized C. roseus ges cloned into XhoI-KpnI sites of pAK056 | This work |

| pAK059 | As pAK058, but gpps replaced with mutated E. coli ispA | This work |

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study, with restriction sites underlined

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| TF:BglII | GAAGATCTGCGATGGCTGTTTTGGCGGATGAGAG |

| TR:AseI | GCTATTAATGTTTGTAGAAACGCAAAAAGGCCATC |

| lacP:F:BglII | GAAGATCTGAACGCCAGCAAGACGTAGCCCAG |

| lacP:R:XbaI | TGCTCTAGAGATCATATGGGAATTCGTAATCATGGTCATAGCTG |

| OF | TATGGTCGACCTGCAGCCAAGCTTGGCTCGAGCCGTCGGTACCTTACAACGTCGTGACTGAT |

| OR | CTAGATCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAGGTACCGACGGCTCGAGCCAAGCTTGGCTGCAGGTCGACCA |

| eGFP:F:EcoRI | GGAATTCCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG |

| eGFP:R:BamHI | CGGGATCCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCA |

| egfp:F:NdeI | GGAATTCCATATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG |

| egfp:R:XbaI | TGCTCTAGATTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCA |

| crtE1:F:NdeI | GGAATTCCATATGGCGGTCGTGACCAACCTCGAGCCGAAAC |

| crtE1:R:HindIII | CCCAAGCTTTTAGAAATCGCGCTCGATCACGAAATC |

| crtE2:F:NdeI | GGAATTCCATATGCAGACCGACCTCAAGACAGCCATG |

| crtE2:R:HindIII | CCCAAGCTTGTTGGAAACGTCCTCCGTTCAGGTC |

| ads:F:NdeI | GGAATTCCATATGAGCCTGACCGAGGAGAAG |

| ads:R:PstI | AACTGCAGTCAGATGGACATCGGGTAGACCAG |

| ispA:F:PstI | AACTGCAGCATAAACAGTAATACAAGGGGTGTATGAGCCATATTCAAATGGACTTTCCGCAGCAACTCGAAG |

| ispA:R:XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTTATTTATTACGCTGGATGATGTAGTC |

| rpoE1:F:XhoI | CCGCTCGAGGAAGACGTGCCCGAAGACGTGGATGCAG |

| rpoE1:R:KpnI | GGGGTACCACGGTCATCGGGAGTCCCTCATG |

| ispAo:F:PstI | AACTGCAGCATAAACAGTAATACAAGGGGTGTATGAGCCATATTCAAATGGACTTCCCGCAGCAGCTGGAG |

| ispAo:R:XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTCACTTGTTGCGCTGGATGATGTAGTC |

| gpps:F:NdeI | GGGAATTCCATATGATGCGCTCCAACCTGTGCC |

| gpps:R:XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTCAGTTGTCGCGGTAGGCGAT |

| ges:F:XhoI | AACTCGAGCATAAACAGTAATACAAGGGGTGTATGAGCCATATTCAAATGTCGCTGCCGCTGGCC |

| ges:R:KpnI | GGGGTACCTCAGAAGCACGGGGTGAAG |

| ispAS80F:F | GAGTGTATCCACGCTTACTTTTTAATTCATGATGATTTACCG |

| ispAS80F:R | AAAGTAAGCGTGGATACACTCAACGGCGGCAGC |

| ispA:F:PstI | AACTGCAGATGGACTTCCCGCAGCAGCTGGAG |

| ispA:R:XhoI | CCGCTCGAGTCACTTGTTGCGCTGGATGATGTAGTC |

FIG 3.

(A) Construction of an IPTG-inducible medium-copy expression vector, pAK032. A 428-bp fragment encompassing the t1 and t2 terminators of the E. coli rrnB operon and a 1.7-kb fragment encompassing the lacI and tac-lacUV5 promoters were PCR amplified from pMMB206 using TF:BglII/TR:AseI and lacP:F:BglII/lacP:R:XbaI primer pairs. Both fragments were cloned into AseI-XbaI sites of pBBR1MCS3 to make pAK032. (B) Comparison of expression efficiencies of pAK032 and pMMB206 (a low-copy IPTG-inducible expression vector) by measuring the fluorescence due to egfp in the strains harboring pMMB206-egfp (pAK024) and pAK032-egfp (pAK040).

Metabolic engineering in Car-1 for geraniol production.

Attempts were made to exploit the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway of A. brasilense for the production of geraniol. For this, the large subunit (LSU) of Catharanthus roseus geranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GPPS), which has been shown to synthesize GPP and GGPP in a 2:1 ratio (27), was codon optimized and cloned in pAK032 to construct pAK032-gpps, designated pAK056 (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the codon-optimized C. roseus geraniol synthase (ges) gene was also cloned to construct pAK032-ges (pAK057). A third derivative of pAK032 was made by cloning both the gpps and ges genes (pAK032-gpps-ges), i.e., pAK058. These constructs were individually mobilized into the Car-1 strain (Fig. 4B) and analyzed for their ability to produce geraniol. After 48 h of growth, Car-1(pAK056) showed a geraniol-specific peak in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. However, its concentration was too low to quantify. Car-1(pAK057), however, showed traces of geraniol after 48 h (Fig. 4C). Car-1(pAK058) eventually produced a distinct geraniol-specific peak in the GC-MS analysis (Fig. 4C and Fig. S1), showing a considerable increase in the production of geraniol up to 77 ± 5.3 μg/liter (33 ± 2.1 μg/g dry weight). A visually distinct decline in the carotenoid content of the Car-1(pAK058) colonies grown on IPTG-supplemented plates (Fig. 4B) clearly indicated that the expression of GPPS and GES via pAK058 directed the flux of the carotenoid pathway toward geraniol synthesis.

FIG 4.

(A) Schematic presentation of the genes present in different expression plasmids constructed for geraniol biosynthesis in A. brasilense. Arrows represent the relative size, location, and transcriptional orientation of the ORFs. (B) Luria-Bertanii plates with (+) and without (−) IPTG showing the colonies of A. brasilense Car-1 harboring pAK032 (a), pAK056 (b), pAK057 (c), and pAK058 (d). (C) GC-MS chromatogram of the hexane extracts; the geraniol-specific peak has been circled. The x axis denotes the retention time in minutes and y axis denotes peak intensity.

The large subunit of C. roseus GPPS has been shown to possess both GPPS and GGPPS activity and produces both GPP and GGPP (∼2:1) (27). However, a site-directed mutation in the E. coli FPP synthase (IspA), which replaces serine 80 with a phenylalanine [IspA(S80F)], was shown to convert it into a GPPS (16). To enhance the intracellular pool of GPP in Car-1, we generated an IspA(S80F) derivative by site-directed mutagenesis and replaced the gpps present in pAK058 with ispA(S80F) to construct pAK059. The GC-MS analysis of Car-1(pAK059) revealed that this replacement increased geraniol production up to 184 ± 5.8 μg/liter (58 ± 6.9 μg/g dry weight). This clearly suggests that the use of IspA(S80F) increases the production and the productivity of geraniol, and GPP is the limiting factor for its synthesis in Car-1. These results also suggest that the geraniol production by Car-1 might be increased further by using a more efficient GPPS.

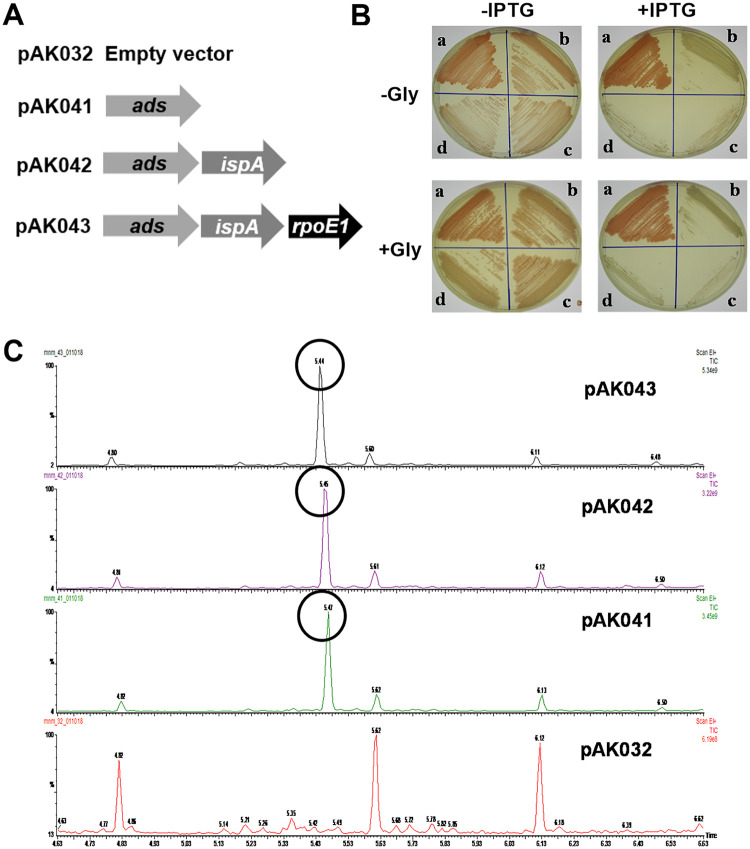

Metabolic engineering in Car-1 for amorphadiene production.

Next, we attempted to evaluate the potential of this strain for producing amorphadiene, a precursor of the antimalarial artemisinin. Since CrtE1 and CrtE2 assays in this study showed that both of these enzymes synthesize and release FPP, we cloned a codon-optimized copy of the Artemisia annua amorphadiene synthase gene (ads) in pAK032 to construct pAK032-ads (pAK041), which was then mobilized into Car-1 (Fig. 5A and B). GC-MS analysis of the hexane extract of the Car-1(pAK041) culture showed an amorphadiene-specific peak (Fig. 5C and Fig. S2). The amount of amorphadiene produced was equivalent to 23 ± 2.2 mg/liter of α-humulene (Table 3) and corresponds to 2.1 ± 0.31 mg/g dry weight (Table 3). This indicated that Car-1 had an endogenous pool of FPP which could be converted into amorphadiene. However, to increase the FPP pool further and to examine its effect on amorphadiene production, we cloned the E. coli FPP synthase gene (ispA) downstream of the ads in pAK041 to construct pAK042 (pAK032-ads-ispA) (Fig. 5A), which was then mobilized into Car-1 (Fig. 5B). A hexane extract of the IPTG-induced culture of Car-1(pAK042) showed an amorphadiene-specific peak (Fig. 5C), which was equivalent to 48 ± 2.5 mg/liter of α-humulene (5.2 ± 0.56 mg/g dry weight) (Table 3). This suggests that expression of ispA increased amorphadiene production by more than 2-fold (Table 2). Furthermore, a distinct decline in the carotenoid content of the Car-1(pAK041) and Car-1(pAK042) colonies grown on IPTG-supplemented plates clearly indicated ADS and ADS-IspA expression-mediated channelization of FPP toward amorphadiene production (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

(A) Schematic presentation of the genes present in different expression plasmids constructed for amorphadiene biosynthesis in A. brasilense. Arrows represent the relative size, location, and translational orientation of the ORFs encoding amorphadiene synthase (ads) of A. annua, farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase (ispA) of E. coli, and extracytoplasmic function sigma factor (rpoE1) of A. brasilense. (B) Luria-Bertani plates with (+) and without (−) IPTG and glycerol (Gly) showing the colonies of A. brasilense Car-1 harboring pAK032 (a), pAK041 (b), pAK042 (c), and pAK043 (d). (C) GC-MS chromatogram of the hexane extracts of Car-1 harboring different expression constructs; the amorphadiene-specific peaks have been encircled. The x axis denotes the retention time in minutes and the y axis denotes peak intensity.

TABLE 3.

Amorphadiene production in LB medium by A. brasilense Car-1 harboring different plasmidsa

| No. | Plasmid present in Car-1 | Amorphadiene production |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| mg/liter | mg/g dry wt | ||

| 1 | pAK032 (empty vector) | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | pAK041 (pAK032-ads) | 23 (±2.2) | 2.1 (±0.31) |

| 3 | pAK042 (pAK032-ads-ispA) | 48 (±2.5) | 5.2 (±0.56) |

| 4 | pAK043 (pAK032-ads-ispA-rpoE1) | 37 (±1.9) | 5.1 (±0.63) |

| 5 | pAK050 (pAK032-ads-ispAo) | 72 (±3.2) | 8.5 (±0.51) |

| 6 | pAK051 (pAK032-ads-ispAo-rpoE1) | 59 (±2.7) | 8.7 (±0.58) |

Data shown are the mean (±SD) from three replicates.

Although Car-1 constitutively produces high levels of carotenoids due to the constitutive expression of RpoE1 (23), we attempted to further enhance the flux toward the isoprenoid pathway by increasing the level of RpoE1 expression in Car-1. For this, rpoE1 of A. brasilense with its native ribosome binding site (RBS) was inserted into pAK042 to construct pAK032-ads-ispA-rpoE1 (pAK043) (Fig. 5A). The Car-1(pAK043) strain showed a growth rate lower than that of the Car-1(pAK042). A hexane extract of the Car-1(pAK043) culture showed an amorphadiene-specific peak (Fig. 5C) equivalent to 37 ± 1.9 mg/liter (5.1 ± 0.63 mg/g dry weight) (Table 3). Since amorphadiene production/g dry weight in Car-1(pAK043) is almost equal to that in Car-1(pAK042) (Table 3), the apparently lower production of amorphadiene by per-liter culture of Car-1(pAK043) than that of Car-1(pAK042) might be a consequence of slower growth and lower yield of biomass of Car-1(pAK043).

In order to further increase the production of amorphadiene in Car-1, we redesigned E. coli ispA according to A. brasilense codon preferences (ispAo) and used it to replace the native ispA gene (sourced from E. coli) present in pAK042 and pAK043 to construct pAK032-ads-ispAO (pAK050) and pAK032-ads-ispAo-rpoE1 (pAK051), respectively. The extracts of Car-1(pAK050) and Car-1(pAK051) cultures showed amorphadiene-specific peaks equivalent to 72 ± 3.2 mg/liter (8.5 ± 0.51 mg/g dry weight) and 59 ± 2.7 mg/liter (8.7 ± 0.58 mg/g dry weight), respectively (Table 3). Since Car-1(pAK051) grows slower than Car-1(pAK050), an almost equal production of amorphadiene in terms of per-gram dry weight by Car-1(pAK050) and Car-1(pAK051) (Table 3) suggests that the lower amorphadiene production by Car-1(pAK051) culture than that by Car-1(pAK050) might also be a consequence of a relatively lower biomass yield for Car-1(pAK051) culture. Use of a codon-optimized copy of ispA (ispAo) led to an increase in amorphadiene production from 48 ± 2.5 mg/liter (5.2 ± 0.56 mg/g dry weight) by Car-1(pAK042) to 72 ± 3.2 mg/liter (8.5 ± 0.51 mg/g dry weight) by Car-1(pAK050) and from 37 ± 1.9 mg/liter (5.1 ± 0.63 mg/g dry weight) by Car-1(pAK043) to 59 ± 2.7 mg/liter (8.7 ± 0.58 mg/g dry weight) by Car-1(pAK051) (Table 3). However, increased expression of RpoE1 in Car-1 seems to inhibit its growth, as the strains harboring rpoE1 expression plasmids (pAK043 or pAK051) grew slower than those lacking plasmid-borne expression of rpoE1 (pAK041, pAK042, or pAK050). These results indicated that, among all the above strains, Car-1(pAK050), which coexpresses ADS and IspAo, was the most efficient strain of A. brasilense for producing amorphadiene.

Optimization of growth conditions for the production of amorphadiene and geraniol.

Further optimization of growth conditions was attempted for efficient production of amorphadiene and geraniol in A. brasilense. Addition of glycerol to the Luria-Bertani (LB) medium led to increased amorphadiene production, from 72 ± 3.2 mg/liter to 94 ± 2.6 mg/liter by Car-1(pAK050) and from 59 ± 2.7 mg/liter to 76 ± 3.2 mg/liter by Car-1(pAK051). However, in terms of amorphadiene production per gram dry weight, addition of glycerol did not show any significant enhancement (Fig. 6B). Cultivation in terrific broth (TB) increased amorphadiene production up to 127 ± 2.1 mg/liter by Car-1(pAK050) and up to 90 ± 2.65 mg/liter by Car-1(pAK051). Addition of glycerol to TB further increased amorphadiene production up to 149 ± 3.4 mg/liter by Car-1(pAK050) and to 109 ± 3.7 mg/liter by Car-1(pAK051). However, in terms of amorphadiene production per gram dry weight, there was no significant enhancement by glycerol supplementation (Fig. 6B). When these cultivation conditions were applied to assess geraniol production, addition of glycerol led to a significant increase in geraniol production by Car-1(pAK058), from 77 ± 5.3 μg/liter to 117 ± 7.6 μg/liter. However, in terms of geraniol production per gram dry weight, there was only a marginal increase (Fig. 6A). Unexpectedly, addition of glycerol resulted in a decline in the production of geraniol by Car-1(pAK059) from 184 ± 5.8 μg/liter (58 ± 6.9 μg/g dry weight) to 120 ± 3.7 μg/liter (35.45 ± 5.0 μg/g dry weight) (Fig. 6A). We noted that the growth of Car-1(pAK059) after the mid-log phase decreased suddenly in the glycerol-supplemented LB medium (data not shown). Cultivation of Car-1(pAK058) and Car-1(pAK059) in the TB medium also severely hampered their growth. These results suggest that glycerol supplementation increases amorphadiene production in LB as well as TB media by increasing the biomass, while TB medium increases amorphadiene productivity. However, glycerol supplementation or use of TB negatively affected geraniol production.

FIG 6.

(A) Effect of different media on amorphadiene production by Car-1(pAK050) and Car-1(pAK051). Each bar shows the mean and standard deviation of values obtained from three replicates. (B) Effect of replacement of Catharanthus roseus gpps with mutated ispA [ispA(S80F)] of E. coli and of glycerol supplementation on geraniol production. The effect of different constructs and media on the production of amorphadiene (A) and geraniol (B) was analyzed by performing multiple pairwise comparisons using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, and P values of <0.05 were considered to represent a significant difference. Different letters show statistically significant differences.

DISCUSSION

By expressing heterologous genes in a carotenoid-overproducing mutant of A. brasilense, we have redirected the native substrate pool of its carotenoid biosynthetic pathway toward the production of geraniol and amorphadiene and have shown the suitability of A. brasilense as a potential host for the production of terpenoids and other secondary metabolites. In S. cerevisiae, the endogenously produced FPP cannot be completely channelized toward the production of heterologous compounds as FPP is necessary for the synthesis of ergosterol (28). Therefore, metabolic engineering for the biotechnological production of the artemisinin precursor amorphadiene and artemisinic acid (9, 14) required upregulation of the endogenous mevalonate pathway to synthesize higher levels of FPP. Squalene synthase, which utilizes FPP for ergosterol synthesis in S. cerevisiae, was downregulated to enhance accumulation of FPP for its conversion to amorphadiene (14).

Production of amorphadiene in E. coli also required engineering of the whole terpenoid backbone biosynthetic genes to increase the substrate pool (7, 9). After a series of metabolic engineering and process optimization steps, the present E. coli strains can produce more than 25 g/liter amorphadiene (29). However, the first attempts to express ADS in E. coli produced only 86 μg amorphadiene/liter (9). Expression of exogenous genes from S. cerevisiae encoding the mevalonate pathway components, along with the gene encoding ADS from A. annua, increased the yield of amorphadiene up to 22.6 mg/liter, which was further enhanced up to 112 mg/liter by the addition of 0.8% glycerol (9). In this study, we obtained up to 23 mg/liter of amorphadiene by expressing ADS alone in the Car-1 mutant strain, which increased further to 94 mg/liter and 127 mg/liter by culturing in glycerol-supplemented LB or TB medium, respectively. This shows that the endogenous pool of FPP in Car-1 might be at par with E. coli strains expressing mevalonate pathway-encoding genes of S. cerevisiae and corroborates our results on in vitro enzymatic assays showing release of FPP by CrtE1 and CrtE2 of A. brasilense. Although the expression of FPP synthase (IspA of E. coli) and ADS in Car-1 doubled amorphadiene production, expression of RpoE1 sigma factor along with ADS and IspA in Car-1 could not increase amorphadiene production further. Since RpoE1 is known to regulate the expression of several other genes in addition to those involved in carotenoid biosynthesis (30), the slower growth of Car-1(pAK043) or Car-1(pAK051) might be due to the overexpression of RpoE1, which might outcompete the housekeeping sigma factor RpoD for core enzyme, leading to an adverse effect on housekeeping functions of the cell.

Production of geraniol by geraniol synthase (GES) requires GPP as a precursor, which is formed by the condensation of isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). Many bacteria, including A. brasilense, do not express specific GPP synthases (GPPS) and hence do not accumulate GPP (31). GPP further condenses with another IPP to form FPP, and FPP condenses with another IPP to form GGPP (32). Our data from the in vitro assays of the recombinant CrtE1 and CrtE2 of A. brasilense Sp7 suggest that both synthesize FPP and GGPP but neither releases GPP. This observation suggested the necessity of expression of heterologous GPP synthase to provide a GPP pool for the synthesis of geraniol. Although E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing Ocimum basilicum GES (ObGES), Abies grandis GPPS, and a heterologous mevalonate pathway could produce up to about 69 mg geraniol/liter (33), initial attempts to produce geraniol in E. coli by expressing ObGES yielded only 185 μg geraniol/liter (34). Expression of a mutated version of FPP synthase [IspA(S80F)] along with the ObGES and exogenous mevalonate pathway genes in E. coli increased the production up to 117 mg/liter geraniol (32, 33, 35).

Our results show that A. brasilense produces considerable amounts of GGPP and FPP but no GPP. When we expressed codon-optimized genes encoding GPPS and GES from Catharanthus roseus in Car-1, it produced only 77 μg geraniol/liter, which is nearly 50% of that produced by E. coli initially (34). However, replacement of C. roseus GPPS with the IspA(S80F) mutant of FPP synthase of E. coli (35) increased geraniol production in Car-1 up to 184 μg/liter. The lower yields of geraniol in A. brasilense observed in this study might be due to the sensitivity of A. brasilense to geraniol, the lower catalytic efficiency of C. roseus GES vis-a-vis ObGES, and the presence of enzymes involved in the degradation of geraniol that are encoded in its genome. Further, the differences might also be due to the type of promoter and copy number of the vector used for expressing GES. Since availability of GPP is a limiting factor in the production of geraniol in A. brasilense, GPP availability can be enhanced by expressing more-efficient GPPS and GES. A higher production of geraniol can also be achieved by preventing geraniol degradation via metabolic engineering (35). In S. cerevisiae also, geraniol was produced by expressing ObGES in an ERG20 mutant, which possessed high GPPS activity (34). Although attempts were made to increase the GPP pool by expressing GPPSs from different plants, all of them failed to produce geraniol to the level produced by the ERG20 mutant (36).

Broad-host-range vectors with high copy numbers and highly efficient and tightly regulated promoters are not available yet for A. brasilense (21). Earlier, we have used pMMB206 (25), which is an RSF1010 replicon-based broad-host-range, low-copy-number (10 copies per cell) expression vector having a lacIq repressor-regulated tac-lacUV5 promoter, for routine complementation and other expression studies in A. brasilense (37). Since the tac-lacUV5 promoter of pMMB206 is weak in nature, the efficiency of expression from this vector is rather low to support expression of the exogenous genes for an efficient conversion of precursor metabolites into the desired products. In addition, it also encodes chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT), which is also known to cause a nonspecific esterification of alcohols, such as conversion of perillyl alcohol into perillyl acetate (38) and geraniol into geranyl acetate (35). To increase the efficiency of expression of the heterologous genes, and to rule out the possibility of CAT-mediated conversion of geraniol into geranyl acetate, we constructed a stronger and inducible broad-host-range expression vector to work in A. brasilense by placing the tac-lacUV5 promoter on pBBR1MCS3 (26). The efficiency of expression from the newly constructed vector (pAK032) was 2.5-fold higher than that from pMMB206. Developing vectors with native inducible promoters from A. brasilense with severalfold higher efficiency can help to further improve yields of the targeted metabolites.

Although the amount of geraniol and amorphadiene produced by the Car-1 mutant is relatively lower than that shown by the other well-developed host-vector systems wherein extensive metabolic engineering has been done (7, 9, 35, 39), this study indicates the potential of this new bacterial system, which can be harnessed by improving and optimizing expression of the pathways leading to an enhanced availability of precursors, preventing biotransformation of target compounds by native enzymes, and improving the efflux efficiency of the desired metabolites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, media, and chemicals.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmids were propagated and maintained in E. coli DH5α (40) using Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with the required antibiotics. A. brasilense (21) strains were routinely grown at 30°C in LB or minimal medium for A. brasilense (MMA) (41). Terrific broth (TB) (42) was also used as a production medium. Broth cultures of A. brasilense and E. coli were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and grown at 30°C and 37°C, respectively, with shaking at 180 rpm in an orbital incubator shaker. Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density of the cultures at 600 nm (OD600). Growth media were from Difco (Becton, Dickinson and Company, France), while high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade organic reagents (ethanol, isopropanol, hexane, decane, dodecane, etc.) were from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). IPP, DMAPP, farnesol, geraniol, geranylgeraniol, and α-humulene were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Plasmid isolation and gel elution/purification kits were purchased from Qiagen (Germany) and Promega (USA), respectively. Restrictions enzymes and primers were obtained from New England BioLabs (USA) and Integrated DNA Technologies (USA), respectively. Nucleotide sequences of the primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Bioinformatics analysis.

The terpenoid backbone and carotenoid biosynthesis pathway of A. brasilense Sp7 were analyzed using the KEGG pathway database, available at https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?abf00900. Genes encoding terpenoid pathway enzymes were identified by analyzing the A. brasilense Sp7 genome, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/11059?genome_assembly_id=676097. Codon optimization of the genes was done using the GenSmart Codon Optimization Tool, available at the GenScript site (https://www.genscript.com/gensmart-free-gene-codon-optimization.html). The optimized sequences were provided to GenScript (USA) for synthesis.

Carotenoid estimation for different A. brasilense strains.

Carotenoid content of A. brasilense Cd, a naturally carotenoid-producing strain of A. brasilense, was compared with that of Car-1, which is a carotenoid-producing Tn5 mutant. Both strains were grown in LB medium with shaking in an orbital shaker for 72 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with chilled MilliQ water, and freeze dried. Carotenoids were extracted by suspending the cell pellet in methanol at 4°C overnight. The methanol extraction was repeated 3 to 4 times for maximum extraction of carotenoids. Carotenoid content was estimated by measuring the absorbance of the methanol extract at 480 nm. The total carotenoids (TC) (μg/g dry weight) was estimated by using equation 1 (43):

| (1) |

where A is absorbance of extract at 480 nm, D is the dilution factor, V is the volume (in milliliters) of methanol, 0.16 is the extinction coefficient of carotenoids, and W is the dry weight of A. brasilense in grams.

In vitro enzyme assays.

The genes encoding CrtE1 and CrtE2 were PCR amplified using crtE1:F:NdeI/crtE1:R:HindIII and crtE2:F:NdeI/crtE2:R:HindIII primer pairs, respectively, and cloned into the expression vector pET28a to generate pET28a-crtE1 (pAK054) and pET28a-crtE2 (pAK055), which were then expressed in E. coli BL21λ(DE3) pLysS (Novagen) and purified using Ni-NTA resin. The prenyl transferase assay of Ni-NTA-purified CrtE1 and CrtE2 was performed in a 300-μl final volume containing 80 μM IPP and 80 μM DMAPP in assay buffer (25 mM 3-morpholino-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid [MOPSO; pH 7.0], 10% glycerol, 2 mM diothreitol (DTT), and 10 mM MgCl2) (27). The reaction mixture was incubated for 8 h at 30°C. Finally, the products as well as the substrates were hydrolyzed by incubating the assay mixture with 10 units of alkaline phosphatase (44). The reaction mixture was extracted with n-hexane (HPLC grade; Sigma-Aldrich) and the extracts were analyzed by GC.

Construction of an improved expression vector.

A 428-bp fragment encompassing the t1 and t2 terminators of the E. coli rrnB operon and a 1.7-kb fragment encompassing the lacI and tac-lacUV5 promoters were PCR amplified from pMMB206 (25) using TF:BglII/TR:AseI and lacP:F:BglII/lacP:R:XbaI primer pairs, respectively. Amplified fragments were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes and inserted between the AseI-XbaI sites of pBBR1MCS3 (26) using a three-fragment-ligation protocol. The lacP:R:XbaI primer was designed to generate NdeI and XbaI restriction sites at the 3′ ends of the amplified fragment. These sites were used to insert an adapter to produce pAK032. The adapter was produced by annealing two oligonucleotides, OF/OR, which were designed to create PstI, XhoI, and KpnI sites in addition to NdeI/XbaI sites. The egfp ORF was amplified from pOT1e (45) using egfp:F:EcoRI/egfp:R:BamHI and egfp:F:NdeI/egfp:R:XbaI primer pairs and cloned into EcoRI/BamHI and NdeI/XbaI sites of pMMB206 and pAK032 to construct pMMB206-egfp (pAK024) and pAK032-egfp (pAK040), respectively. These plasmids were conjugatively mobilized in A. brasilense via E. coli S17-1 (46), and eGFP fluorescence was measured with a FLUOStar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 nm and 508 nm, respectively.

Construction of geraniol biosynthetic operon.

Nucleotide sequences of the gpps large subunit (accession: JX417183) and ges (accession: JN882024) of C. roseus were obtained from GenBank, codon optimized, and synthesized according to the codon preferences of A. brasilense by GenScript, USA. The codon-optimized gpps and ges ORFs were PCR amplified using gpps:F:NdeI/gpps:R:XhoI and ges:F:NdeI/ges:R:XhoI primer pairs and cloned separately into NdeI/XhoI sites of pAK032 to construct pAK056 and pAK057, respectively. gpps:F:NdeI and ges:F:NdeI were designed to exclude the 5′ regions predicted to encode N-terminal signal peptides of 26 amino acids in GPPS and 52 amino acids in GES, respectively. To construct pAK058, the ges ORF was amplified using ges:F:XhoI/ges:R:KpnI primers and cloned into XhoI/KpnI sites of pAK056. The ges:F:XhoI primer was designed to introduce an independent RBS upstream of the ges start codon. E. coli FPP synthase (IspA) was converted into GPP synthase by replacing serine 80 with phenylalanine using overlapping PCR. Primer pair ispAS80F:F/ispAS80F:R was used as the internal and ispA:F:PstI/ispA:R:XhoI as the external primer pair. The mutated ispA [ispA(S80F)] ORF was used to replace the gpps large subunit present in pAK058 to construct pAK059.

Construction of amorphadiene biosynthetic operon.

The nucleotide sequence of the amorphadiene synthase gene (ads) of Artemisia annua was obtained from GenBank (accession: JF951730.1), and a codon-optimized copy of ads ORF was synthesized (GenScript, USA) according to the GC content and codon usage pattern of A. brasilense. The codon-optimized ORF was PCR amplified using the ads:F:NdeI/ads:R:PstI primer pair and cloned into the NdeI/PstI sites of pAK032 to make pAK032-ads (pAK041). The FPP synthase (ispA) ORF was amplified from E. coli genomic DNA using ispA:F:PstI/ispA:R:XhoI and cloned into the PstI/XhoI sites of pAK041 to make pAK032-ads-ispA (pAK042). The ispA:F:PstI primer was designed to introduce an independent ribosomal binding site (RBS) upstream of the ispA start codon. The A. brasilense ECF sigma factor (rpoE1) ORF was amplified along with its native RBS using rpoE1:F:XhoI/rpoE1:R:KpnI primers and cloned into XhoI/KpnI sites of pAK042 to construct pAK032-ads-ispA-rpoE1 (pAK043). Finally, pAK050 and pAK051 were constructed by replacing the original ispA in pAK042 and pAK043 with its codon-optimized (ispAo) copy, respectively. For this, the nucleotide sequence of the ispA gene of E. coli was obtained from GenBank (accession: AP009048.1) and a codon-optimized (ispAo) copy of the ispA ORF was synthesized (GenScript, USA) according to the codon usage pattern of A. brasilense. ispAo was amplified using ispAo:F:PstI/ispAo:R:XhoI primers and cloned into PstI/XhoI sites of pAK042 and pAK043 to replace the original ispA ORF.

Production and extraction of metabolites.

A. brasilense Car-1 cultures harboring different expression constructs were grown to mid-log phase (0.7 to 0.9 OD600) and IPTG was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. After 60 min, dodecane/decane was added to make 0.2% to 2% of the culture volume. These cultures were allowed to grow for 48 h. The decane/dodecane overlay was separated and collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Further extraction of geraniol/amorphadiene was done using hexane (10 to 20% of the culture volume). The process was repeated three times for better extraction. Both the hexane and dodecane/decane phases were concentrated and subjected to GC-MS and GC analysis. After extraction, the cell pellets were dried and weighed to calculate metabolite production in grams of dry weight.

GC/GC-MS analysis.

Geraniol and amorphadiene were identified by GC-MS (Perkin Elmer Clarus 680 gas chromatograph coupled with a Clarus S Q 8C mass spectrometer) and quantified using a model 7890B gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). For GC analysis, 1 μl of each sample was resolved on an HP-5 column (30 mm × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm). The initial oven temperature of 60°C was increased at the rate of 3°C/min to 240°C, at which it was finally held for 2 min. Hydrogen was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.7 ml/min. The detector temperature was maintained at 290°C. Standard curves of geraniol and α-humulene were prepared based on their peak areas obtained from GC analysis of different standards using decane/dodecane/hexane as a solvent.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds from the CSIR-Aroma Mission to A.K.T. and M.N.M. and a grant from the ICAR, New Delhi to A.K.T. S.M., P.P., A.P.D., and A.Z. were supported by fellowships from UGC, ICAR, CSIR, and DST, respectively.

We thank Shree Apte (Bhabha Atomic Research Center, Mumbai) for reading the manuscript. We also thank Ajit K Shasany, CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow, and Dinesh Nagegowda, CSIR-CIMAP, Bengaluru, for their suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breitmaier E. 2006. Terpenes: flavors, fragrances, pharmaca, pheromones. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paduch R, Kandefer-Szerszeń M, Trytek M, Fiedurek J. 2007. Terpenes: substances useful in human healthcare. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 55:315–327. doi: 10.1007/s00005-007-0039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingston DG. 1994. Taxol: the chemistry and structure-activity relationships of a novel anticancer agent. Trends Biotechnol 12:222–227. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maimone TJ, Baran PS. 2007. Modern synthetic efforts toward biologically active terpenes. Nat Chem Biol 3:396–407. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang MC, Keasling JD. 2006. Production of isoprenoid pharmaceuticals by engineered microbes. Nat Chem Biol 2:674–681. doi: 10.1038/nchembio836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts KT, Lee PC, Schmidt‐Dannert C. 2004. Exploring recombinant flavonoid biosynthesis in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Chembiochem 5:500–507. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KE, Wang Y, Simeon F, Leonard E, Mucha O, Phon TH, Pfeifer B, Stephanopoulos G. 2010. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for Taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science 330:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1191652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Q, Roessner CA, Croteau R, Scott AI. 2001. Engineering Escherichia coli for the synthesis of taxadiene, a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of taxol. Bioorganic Med Chem 9:2237–2242. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0896(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin VJ, Pitera DJ, Withers ST, Newman JD, Keasling JD. 2003. Engineering a mevalonate pathway in Escherichia coli for production of terpenoids. Nat Biotechnol 21:796–802. doi: 10.1038/nbt833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter OA, Peters RJ, Croteau R. 2003. Monoterpene biosynthesis pathway construction in Escherichia coli. Phytochemistry 64:425–433. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiling KK, Yoshikuni Y, Martin VJ, Newman J, Bohlmann J, Keasling JD. 2004. Mono and diterpene production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 87:200–212. doi: 10.1002/bit.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang MC, Eachus RA, Trieu W, Ro DK, Keasling JD. 2007. Engineering Escherichia coli for production of functionalized terpenoids using plant P450s. Nat Chem Biol 3:274–277. doi: 10.1038/nchembio875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engels B, Dahm P, Jennewein S. 2008. Metabolic engineering of taxadiene biosynthesis in yeast as a first step towards Taxol (paclitaxel) production. Metab Eng 10:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ro D-K, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, Fisher KJ, Newman KL, Ndungu JM, Ho KA, Eachus RA, Ham TS, Kirby J, Chang MCY, Withers ST, Shiba Y, Sarpong R, Keasling JD. 2006. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature 440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asadollahi MA, Maury J, Møller K, Nielsen KF, Schalk M, Clark A, Nielsen J. 2008. Production of plant sesquiterpenes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: effect of ERG9 repression on sesquiterpene biosynthesis. Biotechnol Bioeng 99:666–677. doi: 10.1002/bit.21581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schweiggert RM, Carle R. 2016. Carotenoid production by bacteria, microalgae, and fungi, p 217–240. In Carotenoids: nutrition, analysis and technology. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi SY, Lee HJ, Choi J, Kim J, Sim SJ, Um Y, Kim Y, Lee TS, Keasling JD, Woo HM. 2016. Photosynthetic conversion of CO2 to farnesyl diphosphate-derived phytochemicals (amorpha-4,11-diene and squalene) by engineered cyanobacteria. Biotechnol Biofuels 9:202. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0617-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beekwilder J, van Houwelingen A, Cankar K, van Dijk AD, de Jong RM, Stoopen G, Bouwmeester H, Achkar J, Sonke T, Bosch D. 2014. Valencene synthase from the heartwood of Nootka cypress (Callitropsis nootkatensis) for biotechnological production of valencene. Plant Biotechnol J 12:174–182. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frohwitter J, Heider SA, Peters-Wendisch P, Beekwilder J, Wendisch VF. 2014. Production of the sesquiterpene (+)-valencene by metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Biotechnol 191:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henke NA, Wichmann J, Baier T, Frohwitter J, Lauersen KJ, Risse JM, Peters-Wendisch P, Kruse O, Wendisch VF. 2018. Patchoulol production with metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Genes 9:219. doi: 10.3390/genes9040219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nur I, Steinitz YL, Okon Y, Henis Y. 1981. Carotenoid composition and function in nitrogen-fixing bacteria of the genus Azospirillum. J Gen Microbiol 122:27–32. doi: 10.1099/00221287-122-1-27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta N, Kumar S, Mishra MN, Tripathi AK. 2013. A constitutively expressed pair of rpoE2–chrR2 in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7 is required for survival under antibiotic and oxidative stress. Microbiology 159:205–218. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.061937-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thirunavukkarasu N, Mishra MN, Spaepen S, Vanderleyden J, Gross CA, Tripathi AK. 2008. An extra-cytoplasmic function sigma factor and anti-sigma factor control carotenoid biosynthesis in Azospirillum brasilense. Microbiology 154:2096–2105. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rai AK, Dubey AP, Kumar S, Dutta D, Mishra MN, Singh BN, Tripathi AK. 2016. Carotenoid biosynthetic pathways are regulated by a network of multiple cascades of alternative sigma factors in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7. J Bacteriol 198:2955–2964. doi: 10.1128/JB.00460-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morales VM, Backman A, Bagdasarian M. 1991. A series of wide-host-range low copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop IR I, Peterson KM. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rai A, Smita SS, Singh AK, Shanker K, Nagegowda DA. 2013. Heteromeric and homomeric geranyl diphosphate synthases from Catharanthus roseus and their role in monoterpene indole alkaloid biosynthesis. Mol Plant 6:1531–1549. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albertsen L, Chen Y, Bach LS, Rattleff S, Maury J, Brix S, Nielsen J, Mortensen UH. 2011. Diversion of flux toward sesquiterpene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by fusion of host and heterologous enzymes. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:1033–1040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01361-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuruta H, Paddon CJ, Eng D, Lenihan JR, Horning T, Anthony LC, Regentin R, Keasling JD, Renninger NS, Newman JD. 2009. High-level production of amorpha-4,11-diene, a precursor of the antimalarial agent artemisinin, in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 4:e4489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta N, Gupta A, Kumar S, Mishra R, Singh C, Tripathi AK. 2014. Cross-talk between cognate and noncognate RpoE sigma factors and Zn2+-binding anti-sigma factors regulates photooxidative stress response in Azospirillum brasilense. Antioxid Redox Signal 20:42–59. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer MJ, Meyer S, Claudel P, Bergdoll M, Karst F. 2011. Metabolic engineering of monoterpene synthesis in yeast. Biotechnol Bioeng 108:1883–1892. doi: 10.1002/bit.23129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohmer M. 1999. The discovery of a mevalonate-independent pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacteria, algae and higher plants. Nat Prod Rep 16:565–574. doi: 10.1039/a709175c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W, Xu X, Zhang R, Cheng T, Cao Y, Li X, Guo J, Liu H, Xian M. 2016. Engineering Escherichia coli for high-yield geraniol production with biotransformation of geranyl acetate to geraniol under fed-batch culture. Biotechnol Biofuels 9:58. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer MJC, Meyer S, Claudel P, Perrin M, Ginglinger JF, Gertz C, Masson JE, Werck-Reinhardt D, Hugueney P, Karst F. 2013. Specificity of Ocimum basilicum geraniol synthase modified by its expression in different heterologous systems. J Biotechnol 163:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Wang C, Yoon SH, Jang HJ, Choi ES, Kim SW. 2014. Engineering Escherichia coli for selective geraniol production with minimized endogenous dehydrogenation. J Biotechnol 169:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao J, Li C, Zhang Y, Shen Y, Hou J, Bao X. 2017. Dynamic control of ERG20 expression combined with minimized endogenous downstream metabolism contributes to the improvement of geraniol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact 16:17. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0641-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mishra MN, Kumar S, Gupta N, Kaur S, Gupta A, Tripathi AK. 2011. An extracytoplasmic function sigma factor co-transcribed with its cognate anti-sigma factor confers tolerance to NaCl, ethanol and methylene blue in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7. Microbiology 157:988–999. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.046672-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alonso-Gutierrez J, Chan R, Batth TS, Adams PD, Keasling JD, Petzold CJ, Lee TS. 2013. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for limonene and perillyl alcohol production. Metab Eng 19:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman JD, Marshall J, Chang M, Nowroozi F, Paradise E, Pitera D, Newman KL, Keasling JD. 2006. High‐level production of amorpha‐4, 11‐diene in a two‐phase partitioning bioreactor of metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng 95:684–691. doi: 10.1002/bit.21017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor RG, Walker DC, McInnes RR. 1993. E. coli host strains significantly affect the quality of small-scale plasmid DNA preparations used for sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 21:1677–1678. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.7.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vanstockem M, Michiels K, Vanderleyden J, Van Gool A. 1987. Transposon mutagenesis of Azospirillum brasilense and Azospirillum lipoferum: physical analysis of Tn5 and Tn5-mob insertion mutants. Appl Environ Microbiol 53:410–415. doi: 10.1128/AEM.53.2.410-415.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hobbs KTC, Tartoff K. 1987. Improved media for growing plasmid and cosmid clones. Focus 9:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gu Z, Deming C, Yongbin H, Zhigang C, Feirong G. 2008. Optimization of carotenoids extraction from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. LWT-Food Sci Technol 41:1082–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Misra RC, Garg A, Roy S, Chanotiya CS, Vasudev PG, Ghosh S. 2015. Involvement of an ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase in tissue-specific accumulation of specialized diterpenes in Andrographis paniculata. Plant Sci 240:50–64. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pothier JF, Wisniewski-Dyé F, Weiss-Gayet M, Moënne-Loccoz M, Prigent-Combaret C. 2007. Promoter-trap identification of wheat seed extract-induced genes in the plant-growth-promoting rhizobacterium Azospirillum brasilense Sp245. Microbiology 153:3608–3622. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.