Effective wastewater management is crucial to ensure safe direct and indirect water reuse; nevertheless, few countries have adopted the virus log reduction value management approach established by the World Health Organization. In this study, we investigated an alternative and/or complementary approach to the virus log reduction value framework for the indirect reuse of activated sludge-treated wastewater effluent. Specifically, we employed a well-accepted statistical approach to identify a statistically sound somatic coliphage threshold value which corresponded to an increased likelihood of human enteric virus detection. This study demonstrates an alternative approach to the virus log reduction value framework which can be applied to improve wastewater reuse practices and effluent management.

KEYWORDS: activated sludge, enteric viruses, fecal indicator bacteria, somatic coliphage, threshold values, wastewater treatment

ABSTRACT

Effective wastewater management is crucial to ensure the safety of water reuse projects and effluent discharge into surface waters. Multiple studies have demonstrated that municipal wastewater treatment with conventional activated sludge processes is inefficient for the removal of a wide spectrum of viruses in sewage. In this study, a well-accepted statistical approach was used to investigate the relationship between viral indicators and human enteric viruses during wastewater treatment in a resource-limited region. Influent and effluent samples from five urban wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in Costa Rica were analyzed for somatic coliphage and human enterovirus, hepatitis A virus, norovirus genotypes I and II, and rotavirus. All WWTPs provide primary treatment followed by conventional activated sludge treatment prior to discharge into surface waters that are indirectly used for agricultural irrigation. The results revealed a statistically significant relationship between the detection of at least one of the five human enteric viruses and somatic coliphage. Multiple logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic curve analysis identified a threshold of 3.0 × 103 (3.5 log10) somatic coliphage PFU per 100 ml, which corresponded to an increased likelihood of encountering enteric viruses above the limit of detection (>1.83 × 102 virus targets/100 ml). Additionally, quantitative microbial risk assessment was executed for farmers indirectly reusing WWTP effluent that met the proposed threshold. The resulting estimated median cumulative annual disease burden complied with World Health Organization recommendations. Future studies are needed to validate the proposed threshold for use in Costa Rica and other regions.

IMPORTANCE Effective wastewater management is crucial to ensure safe direct and indirect water reuse; nevertheless, few countries have adopted the virus log reduction value management approach established by the World Health Organization. In this study, we investigated an alternative and/or complementary approach to the virus log reduction value framework for the indirect reuse of activated sludge-treated wastewater effluent. Specifically, we employed a well-accepted statistical approach to identify a statistically sound somatic coliphage threshold value which corresponded to an increased likelihood of human enteric virus detection. This study demonstrates an alternative approach to the virus log reduction value framework which can be applied to improve wastewater reuse practices and effluent management.

INTRODUCTION

Conventional activated sludge is prepared by an aerobic, secondary wastewater treatment technology that takes advantage of biological processes to remove organic matter and is commonly used in low-, middle-, and high-income countries (1). Frequently, activated sludge wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) effluent does not receive additional treatment, even though it is well-known that pathogen removal can be insufficient for safe water reuse (2–9). This is particularly true for enteric viruses, because traditional activated sludge treatment typically removes 2.02 log10 viruses (1, 10). Currently, human enteric viruses cause a significant fraction of the disease burden related to wastewater pollution worldwide. Direct and indirect wastewater reuse (e.g., for agricultural irrigation, recreational activities in contaminated surface waters) represents a public health risk; thus, the microbial quality of WWTP effluent should be monitored to manage those risks (11, 12).

Fecal indicator bacteria (e.g., fecal coliforms, enterococci, and Escherichia coli) are the indicators most commonly used for assessing WWTP effluent microbial quality (13). They were initially introduced as indicators when Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi was the principal pathogen of concern. Despite their effectiveness for indicating bacterial pathogens, several studies have demonstrated that fecal indicator bacteria do not correlate with enteric viruses in WWTP effluent (14–17). Furthermore, high enteric virus concentrations were detected when fecal indicator bacteria concentrations were low.

While fecal indicator bacteria are not useful viral indicators in wastewater treatment processes (18, 19), country-specific legislation concerning WWTP effluent reuse and discharge frequently relies on fecal indicator bacteria (13). No universally accepted viral indicator or criteria exist to date (10). Some governments now include viral indicators, either human reference viral pathogens, somatic coliphage, or F+ coliphage, to determine WWTP virus reductions (summarized in reference 7). Meta-analyses conducted in wastewater matrices report that bacteriophages, particularly somatic coliphage, are good surrogates of human enteric viruses because of their similar characteristics, their high concentrations, and the low-cost methods that distinguish infectious viruses from noninfectious viruses (10, 20, 21).

Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a multiple-barrier approach to managing WWTP effluent, in which a reference human enteric virus log reduction value is associated with each treatment process (13). Practitioners define the physical and chemical conditions that achieve the target virus log reduction value and then assume that the log reduction value remains constant if the physical-chemical conditions do not change (22). While this approach was accepted among experts, most countries in the world have yet to apply this management approach for a variety of reasons (7). Even though routine monitoring is not required if physical-chemical conditions remain constant, this log reduction value effluent management approach has been met with resistance in many countries because it is difficult to implement into practice, given that it is not a threshold value.

Additionally, the reference human enteric virus analyses required to identify the conditions associated with a target log reduction value are not feasible in many municipal WWTPs in high-income settings, let alone feasible in middle- and low-income country contexts. They require expertise and sophisticated laboratory equipment and are time-consuming and costly, and enteric virus concentrations are frequently below detectable concentrations (4, 22–24). Furthermore, these reference pathogen analyses are typically executed using molecular methods, which cannot distinguish infectious and noninfectious viruses (7, 23, 25). Even though some countries’ legislation focuses on reference enteric virus log reduction values, somatic and F+ coliphages have also been used in the log reduction value management framework (10, 11, 26). Regardless of the human enteric reference virus or indicator used, the log reduction value management framework has been criticized for not effectively protecting public health because it focuses on removal and disregards the variability of human enteric virus concentrations in WWTP influent. Consequently, additional 2- to 3-log10 removal can be needed to ensure safe WWTP discharge and reuse, even if log reduction value targets are met (4).

Prior to the virus log reduction value management approach 2 decades ago, a somatic coliphage threshold (3 log10 PFU/100 ml) associated with infectious enterovirus concentrations was proposed to better manage WWTP effluent discharges (20). However, this threshold value was never applied to management and needs to be recalculated because it was based on a nonrobust statistical approach and considered just one human enteric virus (27). Given the difficulties and disadvantages associated with applying the virus log reduction value management approach, the objective of this study was to determine a statistically sound, robust somatic coliphage concentration threshold useful for monitoring WWTP effluents.

To demonstrate this approach, somatic coliphage and enteric viruses were monitored at five activated sludge WWTPs in the San José metropolitan area, Costa Rica (Fig. 1). The human enteric viruses included in this study were human enterovirus (EV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), norovirus (NoV) genotype I (NoVGI), NoVGII, and rotavirus group A (RV) because they are important causes of outbreaks and diarrheal illness in Costa Rica (28, 29). Data were analyzed using the most-accepted, robust statistical methods (multiple logistic regression models and receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curves [27, 30, 31]) to establish a useful threshold that corresponds to the minimum somatic coliphage concentration associated with increased human enteric virus detection. Since Costa Rican domestic WWTP effluent is currently managed using fecal coliform concentration thresholds that vary on the basis of potential wastewater reuse activities, fecal coliforms were also monitored simultaneously and similar statistical analyses were executed to compare the current bacterial indicator with the proposed viral indicator. Finally, quantitative microbial risk assessment was used to estimate the annual disease burden associated with indirectly irrigating with WWTP effluent that met the proposed somatic coliphage threshold.

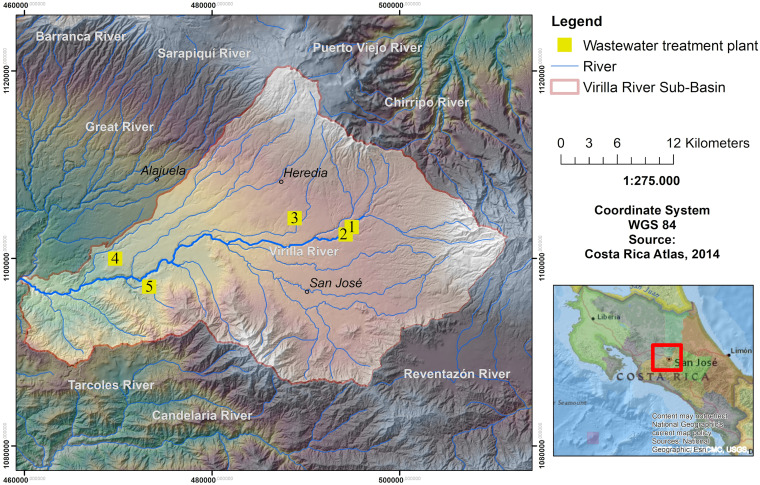

FIG 1.

San José Province, depicting the locations of the five wastewater treatment plants included in the study. San José Province has altitudes ranging from 760 to 1,230 m above sea level and has an average temperature of 22°C year-round. The annual average precipitation ranges from 2,000 to 3,000 mm. Maps were created using ArcGIS (version 10.3) (86).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Fecal coliforms and somatic coliphage in untreated wastewater.

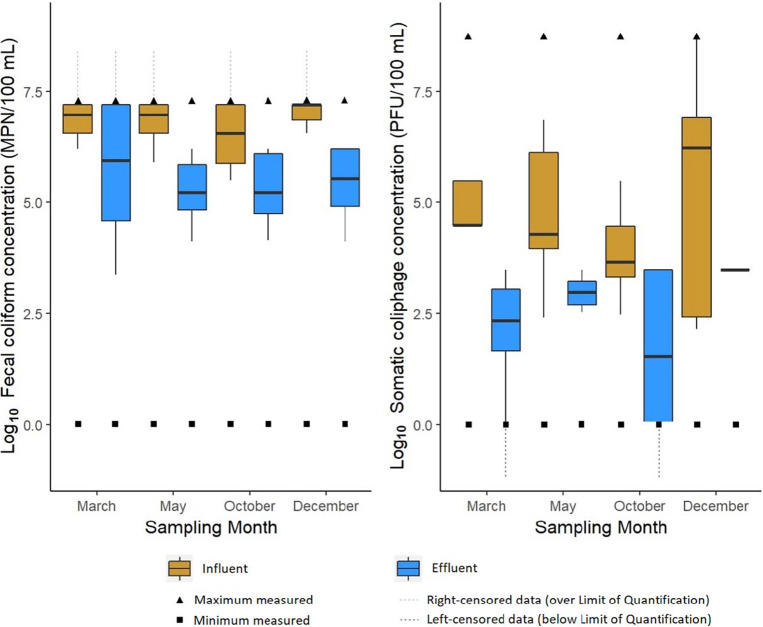

For the five WWTPs investigated during this study, the mean ± standard deviation fecal coliform influent concentration was estimated to be 6.8 ± 6.8 log10 most probable number (MPN)/100 ml, similar to the values summarized in the literature (32). The mean ± standard deviation somatic coliphage influent concentration was 8.7 ± 9.0 log10 PFU/100 ml, which is 3 log10 PFU/100 ml greater than the mean concentration calculated in a recent global meta-analysis (Fig. 2) (11). It is important to note that this recent meta-analysis did not include any Latin American countries and identified statistically significant differences between the geographical locations studied (11). The mean somatic coliphage influent concentrations reported in this study are more comparable to those in Argentina and Colombia, which are likely more similar to those in Costa Rica due to geographic location and water usage (33).

FIG 2.

Global somatic coliphage and fecal coliform concentrations in the influents and effluents of the WWTPs by sampling period.

Fecal coliform and somatic coliphage concentrations are highly variable in treated wastewater.

Both fecal coliform and somatic coliphage concentrations were highly variable in the WWTP effluent studied, with mean ± standard deviation concentrations estimated to be 6.1 ± 6.6 log10 MPN/100 ml and 3.2 ± 3.1 log10 PFU/100 ml, respectively (Fig. 2). The effluent fecal coliform and somatic coliphage concentrations were similar to those in other WWTP studies (3, 20, 34, 35). Variability in the WWTP operational conditions (e.g., the concentration of mixed-liquor suspended solids, temperature, and biochemical oxygen demand [BOD]) is likely responsible for the indicator variability observed in this study (10, 33, 36, 37). Globally, fecal coliform and somatic coliphage mean concentrations were significantly lower in the effluent than in the influent (P < 0.0001). However, with respect to the individual WWTPs, the mean fecal coliform and somatic coliphage concentrations were lower in the effluents than in the influents at three of the five WWTPs (P = 6.0 × 10−6 to 0.02) and all five of the WWTPs (P = 6.0 × 10−7 to 0.04), respectively. Globally, the fecal coliform and somatic coliphage mean ± standard deviation log reduction values were 0.99 ± 1.33 log10 and 2.70 ± 2.60 log10, respectively, and coincided with the ranges previously reported (1).

Human enteric viruses frequently detected in (un)treated wastewater.

Human enteric viruses (EV, HAV, NoVGI, NoVGII, or RV) were detected in WWTP influent and effluent at variable frequencies (Table 1). No statistically significant difference with respect to the frequency of human enteric virus detection was found between the WWTP influent and the WWTP effluent (P > 0.45). RV was the most frequently detected in both influent and effluent samples (47% and 39%, respectively; Table 1), followed by NoVGI (39% and 36%, respectively). Globally, NoVGI was detected two times more frequently than NoVGII. Less than 25% of the samples were positive for EV, and less than 10% of the samples were positive for HAV. It is important to mention that EV and HAV were analyzed in 117 out of 119 water samples; meanwhile, RV and NoV were analyzed in two-thirds of the samples (n = 79 and 80, respectively). Similar to all PCR-based analyses, it is possible that samples with undetected viruses had virus concentrations below the method detection limits or that inhibitors decreased the reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR efficiency (24). Additionally, a mixture of endpoint and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays were effectively used in this study because improved resources were not logistically available. The lack of available resources is common in middle- and low-income countries because funds are limited and supplies are often more expensive than they are in other countries as well as difficult to import. When possible, future studies should use just one type of PCR-based analysis.

TABLE 1.

Results for samples positive for human enteric viruses in wastewater influent and effluent from five activated sludge WWTPs in Costa Rica, 2013

| Variable | No. of positive samples/total no. of samples (%) |

Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influent | Effluent | Total | ||

| Any viral pathogenb | 32/60 (53) | 31/59 (53) | 63/119 (53) | 0.93 |

| Enterovirus | 13/59 (22) | 13/58 (22) | 26/117 (22) | 0.96 |

| Hepatitis A virus | 5/59 (8) | 3/58 (5) | 8/117 (7) | 0.48 |

| Rotavirus | 18/38 (47) | 16/41 (39) | 34/79 (43) | 0.45 |

| Norovirus genotype I | 16/38 (39) | 13/34 (36) | 29/72 (37) | 0.74 |

| Norovirus genotype II | 9/38 (24) | 4/34 (12) | 13/72 (18) | 0.19 |

| All noroviruses | 16/41 (39) | 14/39 (36) | 30/80 (37) | 0.77 |

Pearson chi-square test results for differences in the detection of pathogens.

The total number of water samples positive for any pathogenic virus.

The RV and NoV data presented in this study corroborate the RV and NoV epidemiologies in Central and South American countries, in which they are present throughout the year and peak during the dry season (December to May) (38–40). Similar to our study, NoVGI has previously been quantified in Costa Rican wastewater year-round, with peaks in the dry season, at a WWTP in the province of Puntarenas; in contrast, RV was the most frequently detected virus in our study and the virus quantified at the lowest level in the study of Symonds et al. (41). The difference in RV prevalence between the two studies is likely due to the epidemiology of RV in Costa Rica, where RV infection is more frequent in the greater metropolitan area than in the coastal regions (such as the WWTP in Puntarenas) (42). With respect to EV, the rate of detection in influents and effluents was very low (22%) in comparison to that in the United States (e.g., >92% [25]). This difference may be due to differences in epidemiology and/or methods between the two studies; however, it is difficult to ascertain the origin of these differences because data on the epidemiology of EV in Central America are limited.

Fecal coliforms do not correlate with human enteric virus detection, and no threshold was identified.

Multiple logistic regression models were used to analyze the statistical relationship between fecal coliform concentrations and the detection of human enteric viruses in influent and effluent wastewater samples. The estimated parameters from this logistic regression model were −3.47 × 10−7 (P = 0.258) for fecal coliform concentrations and 0.8881 (P = 0.297) for the dry/rainy season. According to the model, fecal coliforms do not correlate with human enteric virus detection in WWTP influent or effluent (odds ratio [OR] = 0.99, P = 0.26). Despite the lack of a relationship between fecal coliform and human enteric virus detection, ROC analysis was used to estimate a possible fecal coliform concentration associated with the detection of any of the five human enteric viruses analyzed (i.e., to identify an appropriate maximum fecal coliform concentration associated with increased human enteric virus detection). The ROC analysis for fecal coliform and human enteric virus detection did not have an acceptable precision (ROC/area under the ROC curve [AUC] = 0.64). These findings corroborate those of previous studies that did not identify correlations between fecal coliform concentrations and human enteric virus detection (10, 20, 43, 44).

Somatic coliphage concentrations correlate with human enteric virus detection, and a threshold was identified.

Multiple logistic regression models were also used to analyze the statistical relationship between somatic coliphage concentrations (in number of PFU/100 ml) and human enteric virus detection in WWTP influents and effluents. For the WWTP influent, the estimated multiple logistic regression model parameters were 3.98 × 10−10 (P = 0.074) for the somatic coliphage concentration and 0.5606 (P = 0.035) for the dry/rainy season. WWTP influents had a 75% probability of being positive for at least one of the human enteric viruses studied during the dry season in comparison to their probability of detection in the rainy season (OR = 1.75, P = 0.035). Additionally, a significant correlation between somatic coliphage concentrations and human enteric virus detection was identified in WWTP effluents (OR = 1.00, P = 0.01), a finding which was similar to the findings described previously (3, 10, 45). For the WWTP effluents, the estimated multiple logistic regression model parameters were −0.0004 (P = 0.006) for somatic coliphage concentration and 0.8881 (P = 0.297) for dry/rainy season. It is important to note that season was not a significant predictor of human enteric virus detection in WWTP effluents (OR = 2.43, P = 0.297).

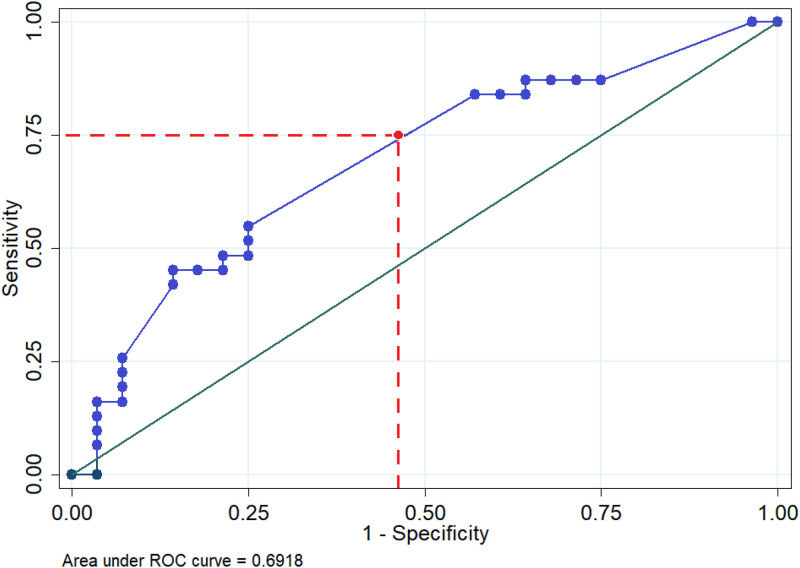

In order to determine an appropriate somatic coliphage concentration associated with an increased probability of human enteric virus detection, ROC analysis was used to estimate the somatic coliphage concentration associated with the detection of human enteric viruses (i.e., any of the five viruses) in WWTP effluents. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.7 (Fig. 3); thus, it had an acceptable discrimination ability. The sensitivity and specificity curves intersected near the 0.526 probability cutoff, where the highest specificity (75%) and sensitivity (54%) were found when the somatic coliphage concentration was 3.5 log10 PFU/100 ml (P = 0.526). Thus, this somatic coliphage threshold (3.5 log10 PFU/100 ml) was the concentration most likely associated with a lack of human enteric virus detection.

FIG 3.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the multiple logistic regression model of somatic coliphage concentrations as a function of human enteric virus detection in conventional activated sludge WWTP effluent.

This somatic coliphage threshold was evaluated for its ability to identify human enteric virus PCR-positive WWTP effluent samples by calculating the positive and negative predictive values (31). The frequencies of true- and false-positive results and true- and false-negative results were calculated for each enteric virus type (Table 2) and were used to calculate the positive and negative predictive values. The positive predictive value was 46%; therefore, 46% of the samples had somatic coliphage concentrations above the threshold and human enteric viruses were detected. The negative predictive value was 33%; thus, 33% of the samples had somatic coliphage concentrations less than the threshold and no human enteric viruses were detected. Using this threshold, only 34.5% of the samples were classified as false negative and would represent a possible human health risk (Table 2). Overall, 65.6% of WWTP effluent samples were safely classified using the proposed somatic coliphage threshold.

TABLE 2.

Relationship between human enteric virus detection and somatic coliphage concentrations above the calculated threshold in WWTP effluent

| Human enteric virusa | No. (%) of WWTP effluent samples with somatic coliphage detection above the threshold |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True positive | False positive | False negative | True negative | |

| Enterovirus (n = 58) | 6 (10.3) | 22 (37.9) | 7 (12.1) | 23 (39.7) |

| Hepatitis A virus (n = 58) | 0 (0) | 28 (48.3) | 3 (5.2) | 27 (46.6) |

| Rotavirus (n = 41) | 6 (14.6) | 23 (56) | 10 (24.4) | 12 (29.3) |

| Norovirus (n = 40) | 6 (15.8) | 13 (31.7) | 7 (18.4) | 14 (36.8) |

| Any virus (n = 58) | 13 (22.4) | 15 (25.9) | 20 (34.5) | 10 (17.2) |

Some samples were positive for more than one human enteric virus.

Similar to the findings of this study, low or undetectable human enteric virus concentrations were measured in WWTP effluents when somatic coliphage concentrations were below 3.5 log10 PFU/100 ml (3, 20, 34, 35, 45, 46). Nevertheless, it is important to note that the results of this study are directly dependent on the efficiencies and detection limits of the methods used. It is possible that the somatic coliphage threshold would be different if different methods (e.g., virus concentration, RNA extraction) were used or if additional/fewer human enteric viruses had been analyzed. Furthermore, this study did not take into consideration the detection of infectious human enteric viruses. Future studies are needed to explore and confirm the somatic coliphage threshold identified in this study. Specifically, studies that take into consideration human enteric virus infectivity are needed. It is also important to analyze how the use of different methods may or may not influence the somatic coliphage threshold identified. Interestingly, the somatic coliphage threshold identified in this study is similar to the threshold previously proposed 2 decades ago (3 log10 PFU/100 ml), even though that study was executed using statistical and virus methods different from those used in the present study, analyzed only human EV, and used cell culture methods (20).

Annual disease burden for indirectly reusing wastewater effluent below the proposed threshold.

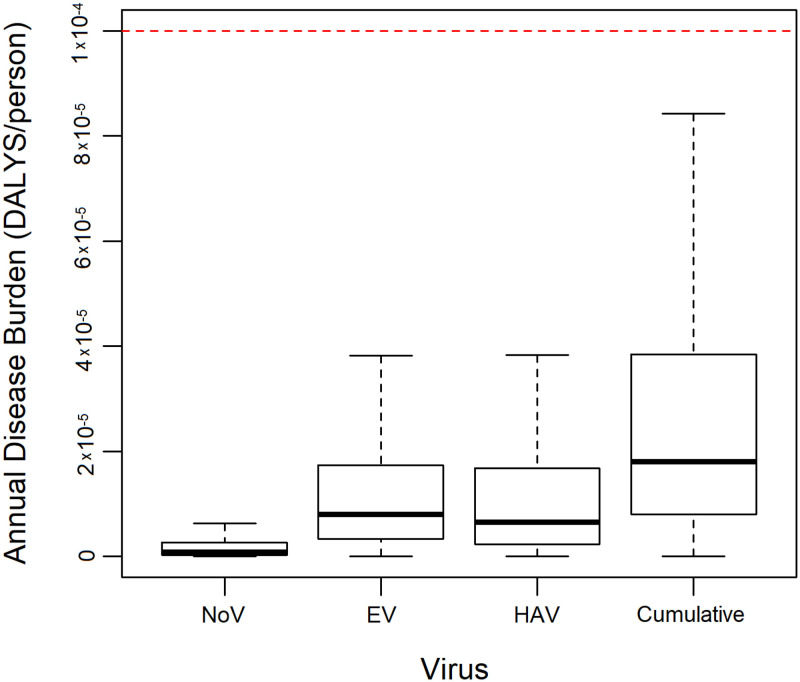

Quantitative microbial risk assessment was used to estimate the annual disease burden for EV, HAV, NoVGI, as well as the cumulative burden (of all three viruses), for an adult farmer irrigating indirectly (75 days per year) with WWTP effluent below the proposed somatic coliphage threshold. The median cumulative annual disease burden per adult farmer was 2.52 × 10−5 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (Fig. 4), which is less than the recommendation of 10−4 (11, 47). EV contributed the most to the cumulative annual disease burden, followed by HAV and NoVGI. The exposure assessment parameter sensitivity analysis indicated that the daily volume ingested (ρ = 0.479, P = 2.2 × 10−16), the WWTP effluent infectious enteric virus concentrations (ρ = 0.471, P = 2.2 × 10−16), and the dilution factor (ρ = −0.466, P = 2.2 × 10−16) rather than the decay-related variables (0.102 ≤ | ρ | ≤ 0.231, P < 2.2 × 10−16) had the most influence on the cumulative annual disease burden estimates. Furthermore, the NoVGI decay rate did not significantly correlate with the cumulative annual disease burden (ρ = −0.017, P = 0.087).

FIG 4.

Estimated annual disease burden for an adult farmer indirectly irrigating with wastewater treatment plant effluent below the somatic coliphage threshold, which was estimated for norovirus genotype I (NoV), enterovirus (EV), and hepatitis A virus (HAV), as well as cumulatively, considering the three aforementioned viruses. The dashed red line identifies the World Health Organization’s annual recommended limit for the additional disease burden caused by wastewater reuse (10−4 DALYs per person).

Based upon the sensitivity analysis results, it is likely that the cumulative annual disease burdens may increase or decrease markedly if the estimated daily volume ingested and/or WWTP effluent infectious enteric virus concentrations were higher or lower, respectively. In order to incorporate uncertainty and variability into this study, WWTP effluent infectious enteric virus concentrations were defined as a uniform distribution between 0 and the maximum theoretical process limit of detection. It was assumed that all viruses were infectious; thus, it is possible that the cumulative disease burden calculated overestimated the risk. Additionally, the cumulative disease burden calculated could underestimate the actual risk if the theoretical process limit of detection was greater than the maximum value estimated. Nevertheless, the theoretical process limit of detection took into account losses associated with the virus concentration and detection.

Since Costa Rican culture lacks habits associated with additional hand-mouth contact (e.g., chewing coca leaves, as in Bolivia), a point value traditionally used in quantitative microbial risk assessment was used, even though it can impact the model output (48). Similarly, it was difficult to identify the dilution factor of the WWTP effluent entering the river due to constant fluctuations in river flow rates and the volume. Consequently, this parameter was defined as a distribution between a conservative (99:1) and a maximum (50,000:1) assumption (49). If the dilution factor was greater, then the cumulative annual disease burden estimates would be much lower. Finally, the cumulative annual disease burden would be greatly affected if the number of days that farmers irrigated indirectly with WWTP effluent was greater or less than the assumed 75 days.

While quantitative microbial risk assessment is a useful tool, it is based upon assumptions that may or may not reflect reality. Consequently, this quantitative microbial risk assessment incorporated the use of parameter distributions to account for this uncertainty and variability. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize that the dose-response curves and parameter distributions may not reflect realistic human populations, which can highly influence model outputs (49, 50). This is particularly true for EV, which is based upon a nonhuman model (48, 51), and NoVGI, because there is no agreement on which parameters are most appropriate (52). Point values were also used for certain parameters when preferred values were previously identified in other studies. Additionally, data from other contexts were used when contextualized data were lacking. Similar to other studies, it is likely that these assumptions influenced the model output (48–50). Although wastewater contains a wide variety of disease-causing viruses, it is not possible to estimate the disease burden of all pathogens, given the lack of disease-related and dose-response data. Consequently, this study incorporated three reference pathogens to calculate the cumulative annual disease burden associated with indirect wastewater reuse with WWTP effluent meeting the somatic coliphage threshold.

Implications for activated sludge WWTP effluent management.

Our study reports a statistically sound somatic coliphage threshold estimation for WWTP effluent management. The use of a somatic coliphage threshold of 3.5 log10 PFU/100 ml is an affordable alternative and/or complement to the virus log reduction value multiple-barrier-system approach and, if implemented, could improve WWTP effluent management in resource-limited regions that have been resistant to the aforementioned approach. Thus, compliance with this threshold would ensure that lower enteric virus concentrations are discharged into nearby rivers with downstream uses in agriculture.

Additionally, the indirect reuse of WWTP effluent meeting the proposed somatic-coliphage threshold was associated with a median cumulative annual disease burden that complies with the WHO recommendation (13, 47). Given the potential of the proposed somatic coliphage to improve activated sludge WWTP effluent management, further research is warranted to validate, improve, and optimize this threshold for use in Costa Rica. Future investigations should include improved disease burden estimates that contain the most context-appropriate data possible, especially with respect to the exposure assessment parameters. Additional research is also needed to validate the way in which such a threshold should be implemented (e.g., geometric mean, single measurement, 95th percentile) to ensure improved wastewater effluent management and, ultimately, better protect public health. Finally, the statistical approach presented here can be implemented in other regions to determine a logical and feasible metric to improve upon existing WWTP discharge legislation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Wastewater treatment plant sample collection.

A total of 119 1.5-liter influent (n = 60) and effluent (n = 59) samples were collected from five urban WWTPs located in the San José metropolitan area, Costa Rica (Fig. 1). All of the WWTPs are small (i.e., they treat waste from 123 to 1,033 inhabitants and receive only domestic wastewater) (5, 6, 53). Their procedures consist of a primary treatment followed by a secondary treatment via conventional activated sludge processes. The WWTP effluents are discharged into the Virilla River, which is also source water for agricultural irrigation. None of these wastewater treatment facilities disinfect the effluent prior to discharge into surface waters. This study was executed in a tropical country, where there are two seasons: (i) the dry season, from December through April, and (ii) the rainy season, from May through November. In order to account for seasonal differences in weather and human enteric virus seasonality, grab samples were collected from each WWTP between 9:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. on three consecutive days in each of the following months in 2013: March, May, October, and December. All samples were collected in sterile, amber bottles and maintained at 4°C until they were processed. All samples were analyzed for somatic coliphage and fecal coliform concentrations. Presence/absence analyses for the following human enteric viruses were carried out on a subset of samples using PCR-based methods: EV (n = 117), HAV (n = 117), NoVGI (n = 72), NoVGII (n = 72), and RV (n = 79).

Fecal coliform analyses.

Fecal coliform most probable number (MPN) concentrations were determined by multiple-tube fermentation (MPN/100 ml), according to method 9221E, within 8 h of collection (54). Briefly, all samples were inoculated in a series of five tubes with lauryl sulfate broth, in which the WWTP influent and effluent samples were serially diluted to a concentration of 1:1,000,000 and 1:100,000, respectively, prior to inoculation. Confirmation was executed after 48 ± 4 h of incubation at 35°C, and an inoculum of each tube with bacterial growth and gas were transferred to EC medium with methylumbelliferyl-β-glucuronide (EC-MUG) broth and were incubated for 24 ± 2 h at 44.5°C; tubes positive for fecal coliforms had bacterial growth and gas characteristics. A positive control (E. coli ATCC 25922), a negative control (S. enterica serovar Enteritidis ATCC 13076), and a blank (containing the dilution buffer as the inoculum) were analyzed alongside all samples. No contamination was observed, and all positive and negative controls generated positive and negative results, respectively.

Wastewater pretreatment for virus isolation and concentration.

All samples were prefiltered with a metal sieve (0.15-mm pore size) in order to break up large organic particles. Viruses were concentrated in accordance with and following section 9510C of Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater (54). Briefly, the prefiltered wastewater sample (1.25 liters) was successively filtered through three filters that had been pretreated with 3% beef extract (pH 7.2; Oxoid, United Kingdom) to remove larger particles and prevent viruses from sticking to the filters: (i) a 47-mm, 80-μm-pore-size glass fiber filter (catalog number 13400-47-Q; Sartorius, Germany); (ii) a 47-mm, 1.2-μm-pore-size nitrate cellulose filter (catalog number 11303-47-N; Sartorius, Germany); and (iii) a 47-mm, 0.4-μm-pore-size acetate cellulose filter (catalog number 11106-47-ACN; Sartorius, Germany). This filtrate was divided into two parts: 250 ml for somatic coliphage analyses and 1 liter for enteric virus analyses. With the exception of the somatic coliphage analyses for WWTP effluent, the filtrate was stored at −70°C prior to human enteric virus concentration and WWTP influent somatic coliphage quantification.

Human enteric virus concentration and detection.

One liter of filtered WWTP influent and effluent was concentrated using a modified adsorption-elution method (method 9510B [54]). The sample pH was adjusted to 3.5 with HCl (0.1 N) and filtered with a 47-mm, 0.2-nm-pore-size cellulose acetate filter (catalog number 1110tr-47N; Sartorius, Germany) to adsorb the viruses onto the filter; approximately three filters were used for each sample in order to filter the entire 1-liter sample. Subsequently, the viruses were eluted off the filter(s) with 15 ml 3% beef extract, pH 9.0. All the eluate was collected and precipitated at 4°C with polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 and 17.5-g/liter NaCl (55). The final virus concentrates (0.5 ml) were stored at −70°C prior to RNA purification. The concentration efficiency of this method ranged from 40% to 90% in previous studies (54, 56). It was also tested with a poliovirus vaccine strain (the Sabin vaccine strain), in which the concentrations of the original and concentrated samples were determined using the Dulbecco plate method (57) with HEp-2 cells. The concentrated sample was 1 log10 more concentrated than it was in the original sample (data not shown).

Viral RNA (50 μl) was obtained from the entire final virus concentrate (0.5 ml) using a NucleoSpin RNA virus kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany), and cDNA (20 μl) was synthesized from 8.0 μl viral RNA using a RevertAid H minus-first-strand cDNA synthesis kit with random hexamers (Thermo Scientific, USA); both of these procedures were done by following the manufacturers’ instructions. Presence/absence analyses for the following human enteric viruses were carried out on a subset of samples using reverse (RT) transcriptase PCR-based methods and previously published assays and conditions (Table 3) (58–61): enterovirus (EV; n = 117), hepatitis A virus (HAV; n = 117), norovirus genotype I (NoVGI; n = 72), norovirus genotype II (NoVGII; n = 72), and rotavirus group A (RV; n = 79). Presence/absence human enteric virus data were generated in this study because previous studies demonstrated a better correlation between enteric virus presence/absence and coliphages than the correlations obtained with quantitative enteric virus data (27, 43). All RT-PCR-based analyses were executed using 2× master mix (Fermentas, USA) with a final reaction volume of 25 μl.

TABLE 3.

Primers and conditions used in RT-PCR and RT-qPCR assays to detect enterovirus, hepatitis A virus, rotavirus group A, and norovirus genotypes I and II

| Virus | Gene | Primer name | Primer sequencea | PCR conditions | Primer final concn | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV | 5′ noncoding region | EV1 | 5′-ATTGTCACCATAAGCAGCCA-3′ | PCRI for EV1 and EV2 (activation cycle of 95°C 5 min and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 70°C for 45 s) | 6.1 mM | 58 |

| EV2 | 5′-TCCGGCCCCTGAATGCGGCTAATCC-3′ | 7.6 mM | ||||

| EV3 | 5′-ACACGGACACCCAAAGTAGTCGGTTCC-3′ | PCRII for EV3 and EV4 (activation cycle of 95°C for 5 min and then 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 70°C for 45 s) | 8.2 mM | |||

| EV4 | 5′-TCCGGCCCCTGAATGCGGCTAATCC-3′ | 7.6 mM | ||||

| HAV | VP1 region | HA1 | 5′-TTGCTCCTCTTTATCATGCTATG-3′ | Activation cycle (95°C for 5 min) | 8.7 mM | 59 |

| HA3 | 5′-TGGTTAAATCTAATGGTCCTCTATA-3′ | 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 46°C for 30 s, and 70°C 30 s | 9.6 mM | |||

| RV | NSP-3 | ROTAS1 | 5′-ACCATCTTCACgTAACCCTC-3′ | Activation cycle (95°C for 5 min) | 0.2 pM | 60 |

| ROTAS2 | 5′-ACCATCTACACATGACCCTC-3′ | 0.2 pM | ||||

| ROTAA | 5′-CACATAACGCCCCTATAGCC-3′ | 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s and 60°C for 40 s | 0.2 pM | |||

| ROTAP | 6FAM-GGGGATGAGCACAATAGTTAAAAGCTAACACTGTCAA-BBQ | 0.2 pM | ||||

| NoVGI | ORF1 | NVG1F | 5′-CGYTGGATGCGNTTCCATGA-3′ | Activation cycle (95°C 5 min) and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 56°C for 60 s | 0.2 pM | 61 |

| NVG1R | 5′-GTCCTTAGACGCCATCATC-3′ | 0.2 pM | ||||

| G1-prob | 6FAM-AGATYGCGRTCYCCTGTCCA-BHQ1 | 0.2 pM | ||||

| NoVGII | ORF1 | NVG2F | 5′-ATGTTYAGRTGGATGAGRTTYTC-3′ | Activation cycle (95°C for 5 min) and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 56°C for 60 s | 0.2 pM | 61 |

| COG2R | 5′-TCGACGCCATCTTCATTCACA-3′ | 0.2 pM | ||||

| G2-prob | JOE-TGGGAGGGCGATCGCAATCT-BHQ1 | 0.2 pM |

BBQ, BlackBerry quencher 650; 6FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; BHQ1, black hole quencher 1; JOE, 6-carboxy-4′,5′-dichloro-2′,7′-dimethoxyfluorescein .

For the endpoint RT-PCR assays (EV and HAV), an Applied Biosystems Veriti 9902 thermocycler was used. A sample was identified to be positive when PCR products with the anticipated size (EV, 113 bp; HAV, 266 bp) were visualized using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis with GelRed. For NoVGI, NoVGII, and RV, presence/absence was determined using RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) with a StepOne real-time PCR thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). A sample was identified as positive if the quantification cycle (Cq) value was less than 35. For samples with a Cq value of greater than 35 and less than 40, the sample was rerun, and all samples with mean Cq values of ≤35 were classified as positive.

In addition to a negative control (sterile water), the following positive controls, specific to each assay, were used for each instrument run: RV-, NoVGI-, and NoVGII-positive fecal samples (Costa Rican National Children’s Hospital), the Sabin 1 (NIBSC 1/528) vaccine strain for EV (University of Costa Rica, Department of Microbiology, Virology Section), and the HAX-70 strain for HAV (University of Costa Rica, Department of Microbiology, Virology Section). All positive controls yielded positive results, and all negative controls were negative. The enteric virus theoretical process detection limit (number of copies/100 ml) was back-calculated using the following equation, which took into account the efficiency published for each step in the molecular analyses as well as the concentration methods used (equation 1):

| (1) |

where the limit of detection is in number of copies per milliliter, c equals the number of copies that could be detected per RT-qPCR (i.e., the lowest copy number detected divided by 2 [the difference between the double-stranded standard curve material and single-stranded viral RNA]), v1 equals the volume of cDNA added to the qPCR mixture (5 μl), V1 equals the total volume of cDNA synthesized (20 μl), E1 equals the worst-case RT efficiency previously reported (19%) (62), v2 equals the volume of RNA in the retrotranscription reaction mixture (8 μl), V2 equals the total volume of RNA purified (50 μl), E2 equals the worst-case viral RNA purification efficiency (90%) (63), v3 equals the volume of PEG concentrate that RNA was purified from (500 μl), V3 equals the total volume of PEG concentrate (500 μl), v4 equals the eluate volume that was PEG concentrated (45 ml), V4 equals the total volume of eluate (45 ml), V5 equals the total volume of wastewater (1,000 ml), and E3 equals the estimated virus concentration efficiency (40%) (56). The limit of detection for the assays could have been as few as 10 copies (J. Nordgren, personal communication) and as great as 1,000 copies (58, 59). Since the limit of detection of each assay was not tested in this study, the limit of detection (c) was defined as 10 copies and 1,000 copies. Thus, the theoretical process limit of enteric virus detection for any given assay was estimated to range from 183 virus copies/100 ml to 18,300 virus copies/100 ml.

Somatic coliphage quantification.

Somatic coliphage concentrations were determined according to methods 9924B (somatic coliphage assay) and 9924E (single-agar-layer method), with modifications: 250-ml sample volumes were filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter (cellulose acetate; catalog number 11107-91 47N; Sartorius, Germany) that had been pretreated with 3% beef extract, pH 7.2 (54, 64). Somatic coliphage concentrations were identified in WWTP effluent samples using a single-layer plaque assay (with undiluted sample) and in WWTP influent samples using a double-layer plaque assay (with a 1:10,000 serial dilution of sample). Analyses used the host strain E. coli ATCC 13706. Positive (phiX174 phage; ATCC 13706-B1) and negative (buffer-only) controls were run alongside the samples. No contamination was observed, and all controls gave the anticipated results.

Data analyses: statistics and indicator concentration threshold evaluation.

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and comparative analyses (two-group comparisons) were executed using R software (version 3.5.3; www.r-project.org) with the appropriate methods for nonparametric uncensored data as well as right- and left-censored data from the NADA package (65). The mean and standard deviation were calculated for somatic coliphages for the WWTP influent and excluded WWTP influent concentrations that were 5 log10 PFU/100 ml below the average (n = 31). These data were excluded because somatic coliphages were analyzed with culture-based analyses that were likely inhibited by high concentrations of household disinfectants (66).

The mean and standard deviation were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method for the following censored data: somatic coliphage WWTP effluent concentrations and fecal coliform WWTP influent and effluent concentrations. All somatic coliphage WWTP effluent concentrations below the detection limits (<1 PFU/100 ml; e.g., left censored) were conservatively censored to 0.9 PFU/100 ml (n = 8). All fecal coliform concentrations greater than the method detection limits (e.g., right censored) were censored to 1 plus the highest detectable concentration (i.e., >8.2 log10 MPN/100 ml for WWTP influent [n = 22] and >6.2 log10 MPN/100 ml for WWTP effluent [n = 11]). The Peto-Prentice test is a nonparametric analysis that is appropriate for censored data. It was used to test the null hypotheses that there was no significant difference in indicator concentrations (somatic coliphage or fecal coliform) between WWTP influents, WWTP effluents, and WWTP influents and effluents combined.

In order to calculate an indicator threshold concentration that corresponds to human enteric virus detection, multiple logistic regression models were created to determine the statistical significance of and the association between each indicator and any human enteric virus detection for WWTP influents and effluents (43). The positive classification for human enteric virus detection was based upon the detection of any of the five viruses, which reflects the existence of a public health risk if any one of the viruses is detected, and was previously recommended for this type of analysis (27). The multiple logistic regression model equation was defined as (equation 2)

| (2) |

where p is human enteric virus detection (PCR positive/negative; dependent and dichotomous variable), β0 is the intercept, β1 and β2 are the regression parameters, χ1 is the indicator (either somatic coliphage or fecal coliform) concentration, and χ2 is the dichotomous variable for season. Analyses were conducted for WWTP influents and effluents separately. The specific WWTP was a factor controlled in the model. Chi-square and unpaired two-sample t test analyses were used to identify significant (P < 0.05) differences between the multiple logistic regression model parameters. Since the WWTP influent multiple logistic regression models did not yield statistically significant relationships, subsequent analyses were conducted only on the WWTP effluent models.

For each indicator’s WWTP effluent multiple logistic regression model, the area under the ROC curves were estimated in order to measure the regression model’s ability to discriminate between effluent samples with and without the detection of any human enteric virus pathogens. The ROC curve is a plot of sensitivity (true-positive rate, y axis) and specificity (false-positive rate, x axis) of the logistic regression model, and it was used to predict the detection of a human enteric virus (any of the five human enteric viruses) in effluent samples. The area under the ROC curve, also known as the ROC/AUC value, is a precision estimate expressed as a continuous value within a range of 0 to 1. The higher that the ROC/AUC value is, the more precise that the logistic prediction model is. The ROC/AUC value and the area under the ROC curve are among the most objective methods for the evaluation of binary classifiers (27, 31) and have previously been used to predict enterovirus presence based upon somatic coliphage concentrations in recreational waters (67). Multiple logistic regression and ROC curve analyses (27, 67) were executed using STATA software (version 13) (68).

The recommended cutoff points for ROC/AUC were used in this study to determine the logistic regression model’s discrimination ability, as follows: 0 to 0.5, null discrimination; 0.7 to 0.8, acceptable discrimination; 0.8 to 0.9, excellent discrimination; and 0.9 to 1.0, exceptional discrimination (31, 69). The multiple logistic regression model’s discrimination ability must be at least acceptable (ROC/AUC ≥ 0.7) in order to identify a statistically sound WWTP effluent indicator threshold concentration associated with an increased probability of human enteric virus detection. Additionally, the indicator concentration parameter in the multiple logistic regression model must have a significant association (P < 0.05) with the detection of any human enteric virus. The WWTP effluent somatic coliphage multiple regression model was the only model to comply with the aforementioned criteria. The somatic coliphage threshold concentration was identified as the concentration associated with the greatest sensitivity and specificity in the ROC analysis.

The calculated somatic coliphage threshold concentration was evaluated for its ability to identify human enteric virus PCR-positive WWTP effluent samples (27, 31). The numbers of true-positive samples (i.e., samples PCR positive for any of the human enteric viruses analyzed and with a somatic coliphage concentration equal to or above the threshold), true-negative samples (i.e., samples PCR negative for any of the human enteric viruses analyzed and with a somatic coliphage concentration below the threshold), false-positive samples (i.e., samples PCR negative for any of the human enteric viruses analyzed and with a somatic coliphage concentration equal to or above the threshold), and false-negative samples (i.e., samples PCR positive for any of the human enteric viruses analyzed and with a somatic coliphage concentration below the threshold) were calculated. Finally, the positive predictive value (i.e., the probability of being PCR positive for any of the human enteric viruses analyzed and having a concentration that exceeded the indicator threshold) and the negative predictive value (i.e., the probability of being PCR negative for any of the human enteric viruses analyzed and having a concentration that was below the indicator threshold) were calculated.

Quantitative microbial risk assessment for indirect reuse of wastewater treatment plant effluent meeting the somatic coliphage threshold.

In order to understand the health risks associated with the proposed somatic coliphage threshold, a quantitative microbial risk assessment was executed for a hypothetical wastewater reuse scenario using EV, HAV, and NoVGI as the reference pathogens. RV was not included in this analysis because adults are not susceptible to RV (70). NoVGII was not included because no dose-response curve currently exists for NoVGII (52). The annual disease burden for an adult farmer indirectly irrigating with WWTP effluent meeting the somatic coliphage threshold was estimated in R software (version 3.5.3; www.r-project.org). For each model parameter defined as a distribution, a set of 10,000 random values was used to calculate the annual disease burdens in order to account for the uncertainty and variability associated with the model parameters.

First, daily exposure was defined for an adult farmer indirectly using the WWTP effluents from this study to irrigate crops, using the following equation (equation 3) for each enteric virus and parameter value/distribution (Table 4):

| (3) |

where c is the WWTP effluent virus concentration when somatic coliphage concentrations are below the threshold, v is the volume of water accidentally ingested by the adult farmer irrigating in 1 day, d is the dilution factor from the WWTP effluent mixing in the river, kd is the mean virus decay rate constant, and t is the decay time (i.e., the amount of time that the virus was in the river prior to irrigation). Similar to other studies, it was assumed that 1 ml of water was accidentally ingested per day of exposure (48, 71). The infectious enteric virus concentration in the WWTP effluent was defined as a uniform distribution between 0 and the maximum theoretical process limit of detection. Virus decay followed a first-order decay equation (49), using mean decay rates determined from experiments with conditions similar to those in the Virilla River (72–74). The WWTP effluent in this study is indirectly reused at distances ranging from 1 m to 3 km from the site of WWTP discharge; thus, decay time was defined as a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 days (75). Since the dilution factor can vary greatly over time and by season, the dilution factor was defined as a uniform distribution between a conservative dilution factor (99:1) and a maximum dilution factor (50,000:1) (49).

TABLE 4.

Quantitative microbial risk model parameter values/distributions and dose-response equations

| Parameter | Units | Value/distribution or equation | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus concn in WWTP effluent (c) | No. of viruses/1 ml | Uniform (0, 182) | This study |

| Vol of water ingested (v) | ml | 1 | 48, 71 |

| Dilution factor (d) | Proportion | Uniform (99, 50,000) | 49 |

| Time in river (t) | Day | Uniform (0, 1) | 49, 75 |

| Mean decay rate (kd) | Day−1 | ||

| Enterovirus | 0.028 | 73 | |

| Hepatitis A virus | 0.22 | 72 | |

| Norovirus genotype I | 0.08 | 74 | |

| Dose-response | |||

| Enterovirus | Exponential | , k = uniform (0.00291, 0.00562) | 51 |

| Hepatitis A virus | Exponential | , k = uniform (0.00005871, 0.001191) | 76 |

| Norovirus genotype I | Fractional Poisson | , P = uniform (0.87, 1), μ = uniform (1, 1,106) | 52, 77, 78 |

| Morbidity ratio (M) | |||

| Menterovirus | Median | 0.9 | 70 |

| Mhepatitis A virus | Median | Uniform (0.25, 0.92) | 76, 79 |

| Mnorovirus | Median | Uniform (0.3, 1) | 80 |

| Total annual days of irrigation | No. of days/farmer | 75 | 48, 81, 82 |

| Disease burden per illness (B) | DALYS/case of illness | ||

| Benterovirus | Uniform (0.0024,0.0150) | 84, 85 | |

| Bhepatitis A virus | Uniform (0.0761, 0.191) | 70 | |

| Bnorovirus | Uniform (0.000371, 0.00623) | 83 | |

| Susceptible fraction of population (Sf) | Proportion | ||

| Sf, enterovirus | 1 | 48 | |

| Sf, hepatitis A virus | 0.717 | 28 | |

| Sf, norovirus | Uniform (0.87,1.00) | 52, 78 |

The daily probability of infection (Pinf) for each virus was then calculated using the dose previously calculated (equation 3) and the previously published dose-response curves and parameter distributions (Table 4). Briefly, the exponential dose-response curve was used for EV and was derived from a study with pigs and porcine enterovirus type 7 (51). The exponential dose-response curve was also used for HAV and was derived from a HAV human challenge study (76). For NoVGI, the fractional Poisson dose-response curve, derived from NoVGI human challenge studies, was used (77). Since there is no agreement among the members of the scientific community with respect to NoV dose-response parameters, they were described as recommended previously (52). The NoVGI aggregation factor (μ) was described as a distribution ranging from minimum to maximum aggregation. The NoVGI genetically susceptible fraction of the population (p) was adjusted to represent Costa Rica’s demographics (52, 78).

Subsequently, the daily probability of illness (Pill) for each virus was calculated with the following equation (equation 4):

| (4) |

where Pinf is the probability of infection previously calculated and M is the morbidity ratio (Table 4) (48, 70, 76, 79–82). The annual risk of illness (Pa) for each virus was then calculated as follows (equation 5):

| (5) |

where Pill is the daily risk of illness (equation 4) and n is the number of days that adult farmers are exposed each year. Similar to other wastewater reuse irrigation studies, it was assumed that farmers irrigated 75 days per year (48, 81, 82). Finally, the annual disease burden (DB; disability-adjusted life years [DALYs] per person) for each virus was estimated as follows (equation 6):

| (6) |

where Pa is the annual risk of illness (equation 5), B is the disease burden per case of illness, and Sf is the susceptible fraction of the population (Table 4). The disease burden per case of illness (B) was not available for Costa Rica (a middle-income country); thus, it was defined as a uniform distribution with minimum and maximum values identified for developing and developed countries (70, 83–85). The NoV-susceptible fraction of the population (Sf) was defined as a uniform distribution for the Costa Rican demographic (52, 78). The EV-susceptible fraction of the population (Sf) was assumed to be 1, given the high EV diversity (48). The HAV-susceptible fraction of the population was 0.717, as defined by its seroprevalence in the adult Costa Rican population (28). Finally, the cumulative annual disease burden per person from the three reference viruses was calculated by adding together the annual disease burden (DB) for each virus. Since the dose calculation usually has the most significant influence on model outputs (50), this quantitative microbial risk assessment’s sensitivity to the exposure assessment (equation 3) input parameters was tested by calculating the Spearman rank order coefficients between the simulated input parameters and the estimated cumulative annual disease burden (α = 0.05).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We recognize the vice rector of investigation at the University of Costa Rica (Vicerrectoría de Investigación de la Universidad de Costa Rica) for funding our research. E.M.S. was funded by U.S. National Science Foundation grant OCE-1566562.

Special thanks go to the participants of the INISA-CDRC University of Miami Scientific Publications Workshop for their valuable suggestions and Eric Morales Mora from INISA-UCR for his help with creating Fig. 1. Finally, we thank Walter Betancourt for his suggestions with respect to the manuscript.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Naughton C, Rousselot O. 2017. Activated sludge In Mihelcic J, Verbyla M (ed), Global water pathogen project, 1st ed. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Luca G, Sacchetti R, Leoni E, Zanetti F. 2013. Removal of indicator bacteriophages from municipal wastewater by a full-scale membrane bioreactor and a conventional activated sludge process: implications to water reuse. Bioresour Technol 129:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.11.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias E, Ebdon J, Taylor H. 2018. The application of bacteriophages as novel indicators of viral pathogens in wastewater treatment systems. Water Res 129:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerba CP, Betancourt WQ, Kitajima M. 2017. How much reduction of virus is needed for recycled water: a continuous changing need for assessment? Water Res 108:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewitt J, Leonard M, Greening GE, Lewis GD. 2011. Influence of wastewater treatment process and the population size on human virus profiles in wastewater. Water Res 45:6267–6276. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruiz Fallas F. 2012. Gestión de las excretas y aguas residuales en Costa Rica. Situación actual y perspectiva. Colegio de Ingenieros Quimicos y Profesionales Afines, San José, Costa Rica. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano D, Amarasiri M, Hata A, Watanabe T, Katayama H. 2016. Risk management of viral infectious diseases in wastewater reclamation and reuse: review. Environ Int 91:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidhu JPS, Sena K, Hodgers L, Palmer A, Toze S. 2018. Comparative enteric viruses and coliphage removal during wastewater treatment processes in a sub-tropical environment. Sci Total Environ 616-617:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2012. Guidelines for water reuse. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency National Risk Management Research Laboratory and U.S. Agency for International Development, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMinn BR, Ashbolt NJ, Korajkic A. 2017. Bacteriophages as indicators of fecal pollution and enteric virus removal. Lett Appl Microbiol 65:11–26. doi: 10.1111/lam.12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nappier SP, Hong T, Ichida A, Goldstone A, Eftim SE. 2019. Occurrence of coliphage in raw wastewater and in ambient water: a meta-analysis. Water Res 153:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Research Council. 2011. Water reuse: expanding the nation’s water supply through reuse of municipal wastewater. Understanding the risks, 1st ed National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. 2006. WHO guidelines for the safe use of wastewater, excreta and greywater in agriculture. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Indicators for Waterborne Pathogens, Board on Life Sciences, Water Science and Technology Board, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council. 2004. Indicators for waterborne pathogens. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baggi F, Demarta A, Peduzzi R. 2001. Persistence of viral pathogens and bacteriophages during sewage treatment: lack of correlation with indicator bacteria. Res Microbiol 152:743–751. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carducci A, Battistini R, Rovini E, Verani M. 2009. Viral removal by wastewater treatment: monitoring of indicators and pathogens. Food Environ Virol 1:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s12560-009-9013-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Review of coliphages as possible indicators of fecal contamination for ambient water quality. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savichtcheva O, Okabe S. 2006. Alternative indicators of fecal pollution: relations with pathogens and conventional indicators, current methodologies for direct pathogen monitoring and future application perspectives. Water Res 40:2463–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yates MV. 2007. Classical indicators in the 21st century—far and beyond the coliform. Water Environ Res 79:279–286. doi: 10.2175/106143006x123085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gantzer C, Maul A, Audic JM, Schwartzbrod L. 1998. Detection of infectious enteroviruses, enterovirus genomes, somatic coliphages, and Bacteroides fragilis phages in treated wastewater. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:4307–4312. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.11.4307-4312.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillai SD. 2006. Bacteriophages as fecal indicator organisms, p 205–222. Goyal SM. (ed), Viruses in foods. Springer US, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito T, Kato T, Hasegawa M, Katayama H, Ishii S, Okabe S, Sano D. 2016. Evaluation of virus reduction efficiency in wastewater treatment unit processes as a credit value in the multiple-barrier system for wastewater reclamation and reuse. J Water Health 14:879–889. doi: 10.2166/wh.2016.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerba CP, Betancourt WQ, Kitajima M, Rock CM. 2018. Reducing uncertainty in estimating virus reduction by advanced water treatment processes. Water Res 133:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haramoto E, Kitajima M, Hata A, Torrey JR, Masago Y, Sano D, Katayama H. 2018. A review on recent progress in the detection methods and prevalence of human enteric viruses in water. Water Res 135:168–186. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitajima M, Iker BC, Pepper IL, Gerba CP. 2014. Relative abundance and treatment reduction of viruses during wastewater treatment processes—identification of potential viral indicators. Sci Total Environ 488-489:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.04.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pouillot R, Van Doren JM, Woods J, Plante D, Smith M, Goblick G, Roberts C, Locas A, Hajen W, Stobo J, White J, Holtzman J, Buenaventura E, Burkhardt W, Catford A, Edwards R, DePaola A, Calci KR. 2015. Meta-analysis of the reduction of norovirus and male-specific coliphage concentrations in wastewater treatment plants. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4669–4681. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00509-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorevitch S. 2016. Comments on the US EPA “Review of coliphages as possible indicators of fecal contamination for ambient water quality.” University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, Chicago, IL: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/32a4/da627003c5663b6b37aeeddde71f9b79ee6d.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor ML, García Z, Holst I, Somogye T, Cunningham L, Visoná KA. 2001. Seroprevalencia de los virus de la hepatitis A y B en grupos etarios de Costa Rica. Acta Med Costarric 43:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. 2017. Guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edition, incorporating the 1st addendum World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 30.White SE. 2020. Statistical methods for multiple variables In Basic & clinical biostatistics, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 31.White SE. 2020. Methods of evidence-based medicine and decision analysis In Basic & clinical biostatistics, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill Education, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harwood V, Shanks O, Korajkic A, Verbyla M, Ahmed W, Iriarte M. 2019. General and host-associated bacterial indicators of faecal pollution In Farnleitner A, Blanch A (ed), Global Water Pathogen Project. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucena F, Duran AE, Moron A, Calderon E, Campos C, Gantzer C, Skraber S, Jofre J. 2004. Reduction of bacterial indicators and bacteriophages infecting faecal bacteria in primary and secondary wastewater treatments. J Appl Microbiol 97:1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrinca AR, Donia D, Pierangeli A, Gabrieli R, Degener AM, Bonanni E, Diaco L, Cecchini G, Anastasi P, Divizia M. 2009. Presence and environmental circulation of enteric viruses in three different wastewater treatment plants. J Appl Microbiol 106:1608–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francy DS, Stelzer EA, Bushon RN, Brady AMG, Williston AG, Riddell KR, Borchardt MA, Spencer SK, Gellner TM. 2012. Comparative effectiveness of membrane bioreactors, conventional secondary treatment, and chlorine and UV disinfection to remove microorganisms from municipal wastewaters. Water Res 46:4164–4178. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerba CP, Kitajima M, Iker B. 2013. Viral presence in waste water and sewage and control methods, p 293–315. In Viruses in food and water. Elsevier, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang C-M, Xu L-M, Xu P-C, Wang XC. 2016. Elimination of viruses from domestic wastewater: requirements and technologies. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 32:69. doi: 10.1007/s11274-016-2018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bucardo F, Lindgren P, Svensson L, Nordgren J. 2011. Low prevalence of rotavirus and high prevalence of norovirus in hospital and community wastewater after introduction of rotavirus vaccine in Nicaragua. PLoS One 6:e25962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.da Silva Poló T, Peiró JR, Mendes LCN, Ludwig LF, de Oliveira-Filho EF, Bucardo F, Huynen P, Melin P, Thiry E, Mauroy A. 2016. Human norovirus infection in Latin America. J Clin Virol 78:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel MM, Pitzer V, Alonso W, Vera D, Lopman B, Tate J, Viboud C, Parashar UD. 2013. Global seasonality of rotavirus disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J 130:1514–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Symonds EM, Young S, Verbyla ME, McQuaig-Ulrich SM, Ross E, Jiménez JA, Harwood VJ, Breitbart M. 2017. Microbial source tracking in shellfish harvesting waters in the Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica. Water Res 111:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ministerio de Salud. 2019. Vigilancia de la salud: enfermedades de notificación individual. Ministerio de Salud, San José, Costa Rica. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harwood VJ, Levine AD, Scott TM, Chivukula V, Lukasik J, Farrah SR, Rose JB. 2005. Validity of the indicator organism paradigm for pathogen reduction in reclaimed water and public health protection. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3163–3170. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3163-3170.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu J, Long SC, Das D, Dorner SM. 2011. Are microbial indicators and pathogens correlated? A statistical analysis of 40 years of research. J Water Health 9:265–278. doi: 10.2166/wh.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costán-Longares A, Montemayor M, Payán A, Méndez J, Jofre J, Mujeriego R, Lucena F. 2008. Microbial indicators and pathogens: removal, relationships and predictive capabilities in water reclamation facilities. Water Res 42:4439–4448. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomila M, Solis JJ, David Z, Ramon C, Lalucat J. 2008. Comparative reductions of bacterial indicators, bacteriophage-infecting enteric bacteria and enteroviruses in wastewater tertiary treatments by lagooning and UV-radiation. Water Sci Technol 58:2223–2233. doi: 10.2166/wst.2008.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose JB, Hofstra N, Murphy HM, Verbyla ME. 2019. What is safe sanitation? J Environ Eng 145:02519002. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001599. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Symonds EM, Verbyla ME, Lukasik JO, Kafle RC, Breitbart M, Mihelcic JR. 2014. A case study of enteric virus removal and insights into the associated risk of water reuse for two wastewater treatment pond systems in Bolivia. Water Res 65:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sunger N, Hamilton KA, Morgan PM, Haas CN. 2019. Comparison of pathogen-derived ‘total risk’ with indicator-based correlations for recreational (swimming) exposure. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 26:30614–30624. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verbyla ME, Symonds EM, Kafle RC, Cairns MR, Iriarte M, Mercado Guzmán A, Coronado O, Breitbart M, Ledo C, Mihelcic JR. 2016. Managing microbial risks from indirect wastewater reuse for irrigation in urbanizing watersheds. Environ Sci Technol 50:6803–6813. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cliver DO. 1981. Experimental infection by waterborne enteroviruses. J Food Prot 44:861–865. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-44.11.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Abel N, Schoen ME, Kissel JC, Meschke JS. 2017. Comparison of risk predicted by multiple norovirus dose-response models and implications for quantitative microbial risk assessment. Risk Anal 37:245–264. doi: 10.1111/risa.12616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mora-Alvarado DA, Portuguez-Barquero CF. 2016. Cobertura de la disposición de excretas en Costa Rica en el periodo 2000–2014 y expectativas para el 2021. Technol Marcha 29:43. doi: 10.18845/tm.v29i2.2690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Public Health Association (APHA), American Water Works Association (AWWA), and Water Environment Federation (WEF). 2005. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 21st ed. American Public Health Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deshpande JM, Shetty SJ, Siddiqui ZA. 2003. Environmental surveillance system to track wild poliovirus transmission. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:2919–2927. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.5.2919-2927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cashdollar JL, Wymer L. 2013. Methods for primary concentration of viruses from water samples: a review and meta-analysis of recent studies. J Appl Microbiol 115:1–11. doi: 10.1111/jam.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dulbecco R, Vogt M. 1954. Plaque formation and isolation of pure lines with poliomyelitis viruses. J Exp Med 99:167–182. doi: 10.1084/jem.99.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sarmiento L, Mas P, Goyenechea A, Palomera R, Morier L, Capó V, Quintana I, Santin M. 2001. First epidemic of echovirus 16 meningitis in Cuba. Emerg Infect Dis 7:887–889. doi: 10.3201/eid0705.017520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arauz-Ruiz P, Sundqvist L, García Z, Taylor L, Visoná K, Norder H, Magnius LO. 2001. Presumed common source outbreaks of hepatitis A in an endemic area confirmed by limited sequencing within the VP1 region. J Med Virol 65:449–456. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pang X, Cao M, Zhang M, Lee B. 2011. Increased sensitivity for various rotavirus genotypes in stool specimens by amending three mismatched nucleotides in the forward primer of a real-time RT-PCR assay. J Virol Methods 172:85–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Japhet MO, Adesina OA, Famurewa O, Svensson L, Nordgren J. 2012. Molecular epidemiology of rotavirus and norovirus in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: high prevalence of G12P[8] rotavirus strains and detection of a rare norovirus genotype. J Med Virol 84:1489–1496. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miranda JA, Steward GF. 2017. Variables influencing the efficiency and interpretation of reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR): an empirical study using bacteriophage MS2. J Virol Methods 241:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Macherey-Nagel. 2014. Viral RNA and DNA isolation user manual: NucleoSpin RNA virus F. Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solano Barquero M, Chacón Jiménez L, Barrantes Jiménez K, Achí Araya R. 2013. Implementación de dos métodos de recuento en placa para la detección de colifagos somáticos, aportes a las metodologías estándar. Rev Peru Biol 19:335–340. doi: 10.15381/rpb.v19i3.1050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee L. 2017. NADA: nondetects and data analysis for environmental data. R package version 1.6-1 R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 66.McDonnell G, Russell AD. 1999. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:147–179. doi: 10.1128/CMR.12.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mocé-Llivina L, Lucena F, Jofre J. 2005. Enteroviruses and bacteriophages in bathing waters. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:6838–6844. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.6838-6844.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.StataCorp LLC. 2013. Stata statistical software: release 13. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berrar D, Flach P. 2012. Caveats and pitfalls of ROC analysis in clinical microarray research (and how to avoid them). Brief Bioinform 13:83–97. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbr008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Havelaar AH, Melse JM. 2003. Quantifying public health risk in the WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality. RIVM report 734301022/2003 RIVM, Bilthoven, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ottoson J, Stenström TA. 2003. Faecal contamination of greywater and associated microbial risks. Water Res 37:645–655. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boehm AB, Silverman AI, Schriewer A, Goodwin K. 2019. Systematic review and meta-analysis of decay rates of waterborne mammalian viruses and coliphages in surface waters. Water Res 164:114898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.114898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Roda Husman AM, Lodder WJ, Rutjes SA, Schijven JF, Teunis P. 2009. Long-term inactivation study of three enteroviruses in artificial surface and groundwaters, using PCR and cell culture. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:1050–1057. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01750-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bae J, Schwab KJ. 2008. Evaluation of murine norovirus, feline calicivirus, poliovirus, and MS2 as surrogates for human norovirus in a model of viral persistence in surface water and groundwater. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:477–484. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02095-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quesada Q ME, Waylen PR. 2012. Diferencias hidrológicas anuales y estacionales en regiones adyacentes: estudio de las subcuencas de los ríos Virilla y Grande de San Ramón, Costa Rica. Cuad Geogr Rev Colomb Geogr 21:167–179. doi: 10.15446/rcdg.v21n2.32218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weir MH. 2020. A data simulation method to optimize a mechanistic dose-response model for viral loads of hepatitis A. Microb Risk Anal 15:100102. doi: 10.1016/j.mran.2019.100102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Messner MJ, Berger P, Nappier SP. 2014. Fractional Poisson—a simple dose-response model for human norovirus. Risk Anal 34:1820–1829. doi: 10.1111/risa.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morera B, Barrantes R, Marin-Rojas R. 2003. Gene admixture in the Costa Rican population. Ann Hum Genet 67:71–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ward R, Krugman S, Giles JP, Jacobs AM, Bodansky O. 1958. Infectious hepatitis. N Engl J Med 258:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195802272580901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Soller JA, Schoen M, Steele JA, Griffith JF, Schiff KC. 2017. Incidence of gastrointestinal illness following wet weather recreational exposures: harmonization of quantitative microbial risk assessment with an epidemiologic investigation of surfers. Water Res 121:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seidu R, Heistad A, Amoah P, Drechsel P, Jenssen PD, Stenström TA. 2008. Quantification of the health risk associated with wastewater reuse in Accra, Ghana: a contribution toward local guidelines. J Water Health 6:461–471. doi: 10.2166/wh.2008.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mara DD, Sleigh PA, Blumenthal UJ, Carr RM. 2007. Health risks in wastewater irrigation: comparing estimates from quantitative microbial risk analyses and epidemiological studies. J Water Health 5:39–50. doi: 10.2166/wh.2006.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mok HF, Barker SF, Hamilton AJ. 2014. A probabilistic quantitative microbial risk assessment model of norovirus disease burden from wastewater irrigation of vegetables in Shepparton, Australia. Water Res 54:347–362. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Howard G, Feroze Ahmed M, Gaifur Mahmud S, Teunis P, Davison A, Deere D. 2007. Disease burden estimation to support policy decision-making and research prioritization for arsenic mitigation. J Water Health 5:67–81. doi: 10.2166/wh.2006.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Prüss-Üstün A, Bos R, Gore F, Bartram J. 2008. Safer water, better health: costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ortiz-Malavasi E. 2014. Atlas de Costa Rica. Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica, Cartago, Costa Rica. [Google Scholar]