Abstract

Objective

The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) is the most commonly used clinician-rated evaluation tool for Tourette syndrome (TS), with established reliability and validity. This study aims to determine whether the YGTSS is a valid parent-reported assessment in the TS population.

Design

A prospective cohort study.

Setting

A major medical centre in Taiwan.

Methods

A total of 594 patients were enrolled. A revised traditional Chinese version of the YGTSS was made available to parents via Google docs. Parents were encouraged to complete the YGTSS the day before each outpatient clinic visit. At each visit, a paediatric neurology fellow also administered the YGTSS assessment. We investigated whether differences in scores between physicians and parents changed as the number of parent evaluations increased. The results of the physician assessments were also taken as the expert standard for evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of the parent-reported assessments was conducted for the same visit.

Results

The differences in the YGTSS scores between participants and physicians were small. The mean difference in the total assessment score was 4.15 points. As the number of times the parent evaluation was performed increased, the difference between the parent and physician scores decreased. Discrimination of moderate-to-severe attacks was good using the parent-assessed YGTSS (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, 0.858; 95% CI 0.839 to 0.876). The sensitivity for detecting a moderate-to-severe attack by YGTSS parent assessment was 79.7% (95% CI 76.6 to 82.8), and the specificity was 91.8% (95% CI 89.9 to 93.7).

Conclusion

The parent-reported YGTSS is a promising tool for TS assessment, demonstrating good discriminative ability for disease severity, with user precision increasing with experience.

Keywords: paediatric neurology, paediatric neurology, public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study evaluated the hypothesis that the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) is a valid tool for parent-reporting, allowing for better communication and decision-making between doctors and patients.

It is difficult to train many parents repeatedly to ensure them to achieve an acceptable level before they posted their scores, and the internal reliability may be difficult to be evaluated.

There may also have been variability in the YGTSS evaluations from pedestrians.

Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is characterised by persistent motor and vocal tics that begin before 18 years of age, and it is estimated to affect 6 per 1000 children.1 The clinical presentation of TS is complex, as the symptoms may wax and wane in frequency, intensity and type.2 3 The severity is influenced by multiple factors, including stress and social interactions,4–6 making clinical assessment challenging. The most widely used measure to assess the severity of TS is the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS),7 8 a clinician-administered, semistructured interview that assesses tic and tic-related impairment severity over the previous week.

The YGTSS includes a symptom checklist for motor and vocal tics. Both motor and vocal tics are assessed for symptom number, frequency, intensity, complexity and interference on a 0–5 Likert scale. Scores from each dimension are totalled to reflect the severity of motor tics (range 0–25), vocal tics (range 0–25) and combined tics (range 0–50). A separate tic-related impairment scale, scored from 0 to 50, is also included. Although several other assessments have been developed, the YGTSS is still the most commonly used, with established reliability and validity.7 9–12

In practice, clinicians do rely in part on patient report to make their assessment; that is, not all tics present during the interview.13 The use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) has the potential to narrow the gap in clinical manifestations observed between clinicians and patients and to help adjust treatment plans.14 15 Several self-report instruments for TS have been developed for this purpose. The Proxy Report Questionnaire for Parents and Teachers and the Apter 4-questions are limited by insufficient validation and relatively low specificity.12 16 17 The Premonitory Urges for Tics Scale has shown good psychometric properties; however, it is not acceptable for patients younger than 10 years of age.12 18 This study evaluates the hypothesis that YGTSS is a valid tool for parent-reporting in the TS population. Such a tool would allow for better communication and decision-making between doctors and patients, and patient satisfaction regarding their care may also improve.

Methods

Participants

Data collection

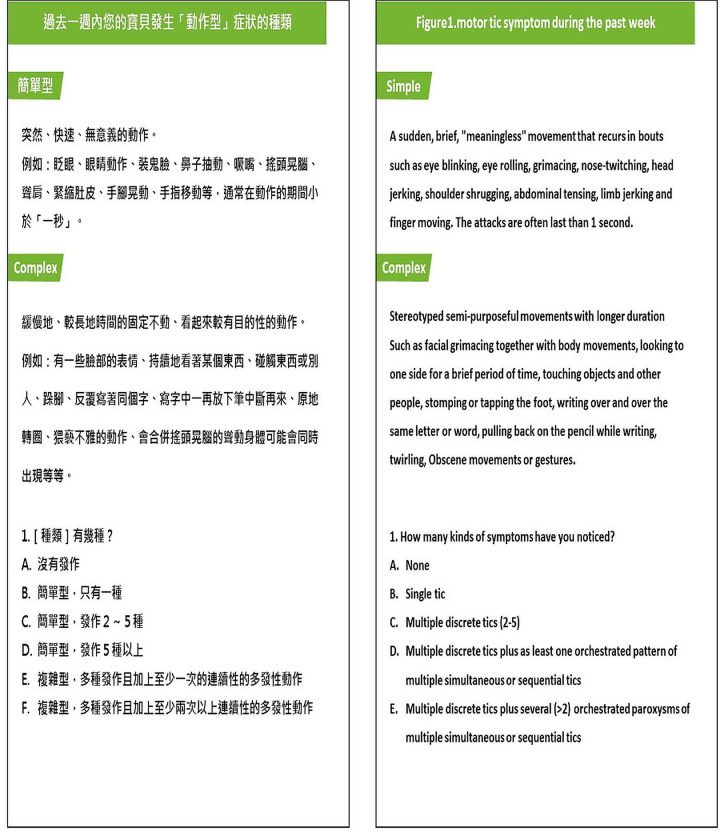

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taiwan. A database was created to collect patient information. Paediatric patients with TS who are regularly followed up in the Taipei Mackay Memorial Hospital were enrolled after informed consent was provided by their parents. The authors carried out a Chinese translation of the YGTSS. Physicians in the Division of Paediatric Neurology, Department of Paediatrics, MacKay Children's Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan reviewed the contents to reach a consensus, and differing perspectives were resolved by group discussions. Beginning in June 2018, a revised traditional Chinese version of the YGTSS was made available to parents via Google docs (figure 1). On introduction of the assessment to parents, a paediatric neurologist explained the use of the assessment scales to make sure parents clearly understood how to rate their symptoms. Parents were encouraged to complete the YGTSS the day before each outpatient clinic visit. On the date of the visit, a paediatric neurology fellow was assigned to the patients by convenience sampling in the waiting room and also administered the YGTSS. The parents and the paediatric fellows were blind to the YGTSS results of the other. Some patients were administered the YGTSS evaluation by both the parents and the paediatric fellow during the same visit. The attending physicians used the YGTSS results as a reference for making medical decisions during the visit. Patient age and sex, date of visit and parent-assessed or paediatric-fellow-administered YGTSS scores were recorded.

Figure 1.

Revised traditional Chinese version of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale made available via Google docs.

Statistical analyses

We first evaluated the absolute differences in the YGTSS scores by subtracting the scores of parents from that of physicians. We also assessed the difference between the two measurements across multiple visits using linear regression. To adjust for correlations in the data due to being collected at multiple times by the same participants, the generalised estimating equation (GEE) method19 was adapted to account for clustering of participants in the evaluation of score differences.

We also dichotomised tic attack as mild or moderate/severe by defining a mild attack as a YGTSS score <20 and a moderate-to-severe tic attack as >20.20 The discriminatory power of the parent-reported YGTSS for a moderate-to-severe attack was assessed by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) based on a logistic regression model with GEE. Feedback from the parents was collected by convenience sampling at outpatient clinics. All p values were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software for Windows, V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or planning of this study.

Results

Study population

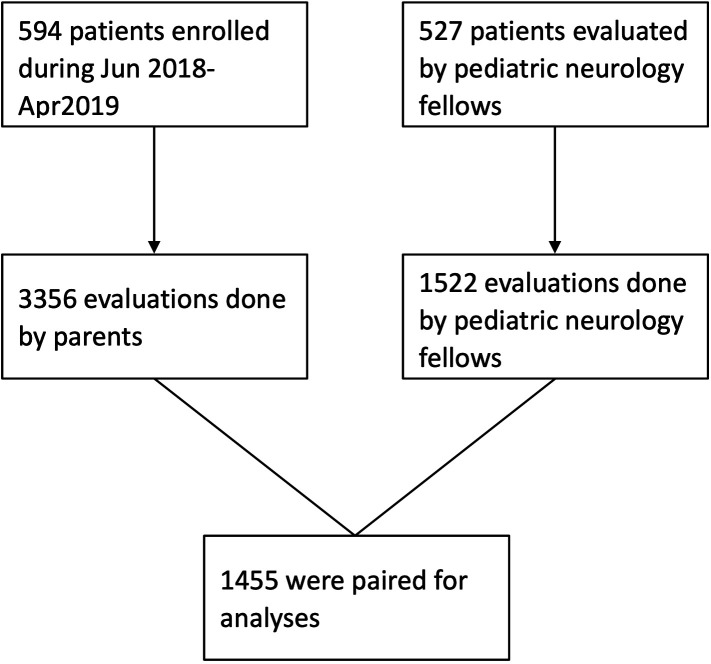

A total of 594 patients were enrolled in this study between June 2018 and April 2019, with 3356 evaluations contributed by their parents. On average, each participant contributed 5.65 parent-reported YGTSS evaluations during the study period. Among these parent reports, 1455 were paired with simultaneous evaluations by paediatric fellows and were used for analyses. The final analysis included 527 patients. The mean patient age was 8.8 years (SD, 2.97), and 82.5% (n=435) of the patients were men. A flow chart of the patient selection process is illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of patient selection.

Comparison of assessment scores between participants and physicians

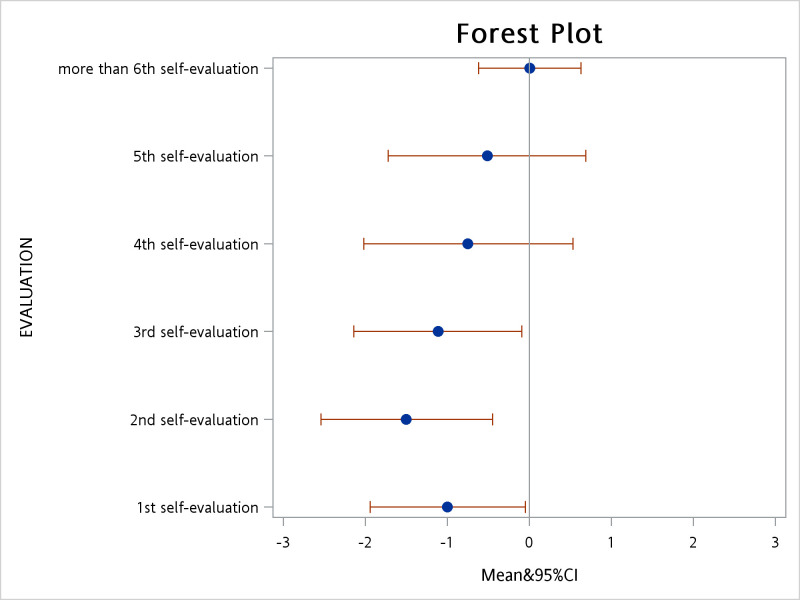

The differences in the YGTSS scores between participants and physicians were small (table 1). The mean difference in the total assessment score was 4.15 points, with the greatest difference being for ‘tic-related impairments’. As the number of times the parent evaluation was completed increased, the difference between the parent and physician scores decreased. After taking parent clustering into account, the absolute difference in total scores between participants and physicians decreased by 0.24 points (95% CI 0.14 to 0.34; p<0.001) for each repetition of the assessment. A subgroup analysis of the combined tic severity category revealed an absolute average difference of 2.40 points. The absolute difference in combined tic severity decreased by 0.17 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.22; p<0.001) for each repetition of the assessment. After participants completed the assessment four times, the difference between participant and physician scores was no longer significant (figure 3).

Table 1.

Comparison of parent-assessed and physician-assessed YGTSS scores according to assessment category*

| Assessment category | Mean difference (points) | 95% CI |

| Entire assessment (all categories) | 4.15 | 3.82 to 4.48 |

| Motor tic severity | 1.17 | 1.07 to 1.28 |

| Vocal tic severity | 1.23 | 1.11 to 1.35 |

| Combined tic severity | 2.40 | 2.22 to 2.58 |

| Tic-related impairment | 2.41 | 2.14 to 2.68 |

*n=1455.

YGTSS, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale.

Figure 3.

Distribution of average score differences.

Diagnostic accuracy of the YGTSS parent evaluation

The power of discriminating moderate-to-severe attacks with the YGTSS parent assessment was good (AUROC, 0.858; 95% CI 0.839 to 0.876). The specificity for detecting a moderate-to-severe attack using the YGTSS parent assessment was significantly high. Of 819 physician assessments of mild attacks, 752 were in accordance with that of the parents, yielding a specificity of 91.8% (95% CI 89.9 to 93.7). In 636 physician assessments of moderate-to-severe attacks, 507 were in accordance with that of the parents, yielding a sensitivity of 79.7% (95% CI 76.6 to 82.8).

Evaluation of feedback

Most comments from participants were positive, as the following examples indicate:

After assessment of my child, I know better what the doctor needs to know, and this process also helps me better understand how to take care of my child.

With these long-term, objective trends in my results, I think discussing the goals of treatment with doctors is clearer.

Feedback taken by convenience sampling from physicians at hospital outpatient clinics was also encouraging:

Being able to understand the patient’s condition outside of the hospital allows me to communicate more effectively with caregivers.

Discussions

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the potential use of the YGTSS as a parent-reported measure of tic severity in children with TS. The results showed an overall good ability to discriminate a moderate-to-severe TS attack via parent-reporting (AUROC, 0.858). The sensitivity and specificity for detecting a moderate-to-severe TS attack were reasonably high. With repeated practice responding to the assessment, the parent-reported scores became similar to those of physicians, with no difference after the fourth assessment. Our results indicate that the YGTSS, the most widely used TS assessment tool, may be as accurate when used by a child’s parent as it is when administered by the child’s clinician.

In this study, we used a step-by-step online Google doc interface to help the participants fill out the forms with little difficulty. The online parent-reported YGTSS database also allowed participants to complete the evaluation without time and space limits, and more than 3000 parent evaluations submitted during the study period are one factor contributing to the efficiency of the system. The feedback from both parents and clinicians was positive, and the database continues to grow as the number of parent-reported submissions increases. Paediatric neurologists currently often rely on parent-reported assessments to adjusting treatment plans.3 4 As self-assessments allow parents and clinicians to share the same information regarding a patient’s condition, the communication is more fluent and efficient.21 22

Another reason for our positive results is that the parents were aware of the disease and highly motivated to be involved in the management of their child’s TS. They may be more likely to present precise evaluations if possible. During the multiple interactions about the conditions with their clinicians, parents became more practiced and accurate with their evaluations. Patients generally welcome systems that routinely use PROMs.14 The parent-reported YGTSS correlates highly with factors that have value to clinicians. Even for the clinician-administered YGTSS, the interviewer relies heavily on patients’ and their family members’ insights, as patients may not present with the full range of tics during the interview. As a result, parent-reporting may more closely reflect the actual patient condition.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the participants were parents of children with TS, and most of them had already participated in regular follow-up at our outpatient clinics. Thus, these parents may have been more aware of their child’s symptoms, allowing for an easier understanding of the YGTSS parameters, resulting in a high correlation between the responses of the parents and physicians. Second, as more than 500 patients were included in the database, it was difficult to provide parents intensive training to ensure that they had achieved an acceptable level of performance before they began submitting their scores; thus, the internal reliability may be difficult to be evaluated. There may also have been variability in the YGTSS evaluations from paediatric fellows. However, these results are representative of real clinical situations. Third, the paediatric fellows visit and evaluate the patients in the waiting room by convenience sampling, which may have led to sampling bias. Fourth, in our cohort there were only a few patients newly diagnosed with TS. As a result, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses for these patients, comparing between those whose child was recently diagnosed and thus were less familiar with the symptoms versus those whose child had the diagnosis for quite a while and were therefore very familiar with the symptoms. We also did not adjust for important patient characteristics such as severity of tics and duration since initial diagnosis as that information was lacking. Lastly, the evaluations from the physicians were not performed simultaneously with the participants. Since the physicians evaluated information by directly observing patients, the symptoms may have differed from those at the time of the parent-reporting.

Conclusion

The parent-reported YGTSS is a promising tool for TS assessment, demonstrating good discriminative ability for disease severity, with user precision increasing with experience.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Chen-Yang Hsu (Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan) for the in-depth discussion on statistical methods. The authors thank Dr James F Leckman (Yale Child Study Center, New Haven, Connecticut, USA) and Dr Jung-Chieh Du (Department of Pediatrics, Taipei City Hospital, Zhongxiao Branch, Taipei, Taiwan) for the development of Chinese version of Yale Global Tic Severity Scale.

Footnotes

M-YH and Y-CS contributed equally.

Contributors: M-YH analysed and interpreted the data. J-YH, C-HY and Y-JL interpreted the data and contributed to the manuscript development. C-SH supervised the study and interpreted the data. Y-CS analysed the data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was initiated after approval from the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taiwan.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Jeon S, Walkup JT, Woods DW, et al. Detecting a clinically meaningful change in tic severity in Tourette syndrome: a comparison of three methods. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;36:414–20. 10.1016/j.cct.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramovitch A, Reese H, Woods DW, et al. Psychometric properties of a self-report instrument for the assessment of tic severity in adults with tic disorders. Behav Ther 2015;46:786–96. 10.1016/j.beth.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin H, Yeh C-B, Peterson BS, et al. Assessment of symptom exacerbations in a longitudinal study of children with Tourette's syndrome or obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:1070–7. 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eapen V, Fox-Hiley P, Banerjee S, et al. Clinical features and associated psychopathology in a Tourette syndrome cohort. Acta Neurol Scand 2004;109:255–60. 10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang S, Himle MB, Tucker BTP, et al. Initial psychometric properties of a brief Parent-Report instrument for assessing tic severity in children with chronic tic disorders. Child Fam Behav Ther 2009;31:181–91. 10.1080/07317100903099100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva RR, Munoz DM, Barickman J, et al. Environmental factors and related fluctuation of symptoms in children and adolescents with Tourette's disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995;36:305–12. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01826.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, et al. The Yale global tic severity scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989;28:566–73. 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho C-S, Chiu N-C, Tseng C-F, et al. Clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole in short-term treatment of tic disorder in children and adolescents: a naturalistic study. Pediatr Neonatol 2014;55:48–52. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Yale global tic severity scale. Psychol Assess 2005;17:486–91. 10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Storch EA, De Nadai AS, Lewin AB, et al. Defining treatment response in pediatric tic disorders: a signal detection analysis of the Yale global tic severity scale. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2011;21:621–7. 10.1089/cap.2010.0149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho C-S, Chen H-J, Chiu N-C, et al. Short-Term sulpiride treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorder. J Formos Med Assoc 2009;108:788–93. 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60406-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martino D, Pringsheim TM, Cavanna AE, et al. Systematic review of severity scales and screening instruments for tics: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord 2017;32:467–73. 10.1002/mds.26891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conelea CA, Woods DW. The influence of contextual factors on tic expression in Tourette's syndrome: a review. J Psychosom Res 2008;65:487–96. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson EC, Eftimovska E, Lind C, et al. Patient reported outcome measures in practice. BMJ 2015;350:g7818. 10.1136/bmj.g7818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 2012;366:780–1. 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cubo E, Sáez Velasco S, Delgado Benito V, et al. Validation of screening instruments for neuroepidemiological surveys of tic disorders. Mov Disord 2011;26:520–6. 10.1002/mds.23460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linazasoro G, Van Blercom N, de Zárate CO. Prevalence of tic disorder in two schools in the Basque country: results and methodological caveats. Mov Disord 2006;21:2106–9. 10.1002/mds.21117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods DW, Piacentini J, Himle MB, et al. Premonitory urge for tics scale (puts): initial psychometric results and examination of the premonitory urge phenomenon in youths with tic disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2005;26:397–403. 10.1097/00004703-200512000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 1986;42:121–30. 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallee F, Kohegyi E, Zhao J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial demonstrates the efficacy and safety of oral aripiprazole for the treatment of Tourette's disorder in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2017;27:771–81. 10.1089/cap.2016.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crandall W, Kappelman MD, Colletti RB, et al. ImproveCareNow: the development of a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease improvement network. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:450–7. 10.1002/ibd.21394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lannon CM, Peterson LE. Pediatric collaborative networks for quality improvement and research. Acad Pediatr 2013;13:S69–74. 10.1016/j.acap.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.