Abstract

Introduction

This clinical trial is designed to evaluate the effect of multiple-dose tranexamic acid (TXA) on perioperative blood loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods and analysis

A randomised, single-blinded, parallel-controlled study will be designed. Patients with RA (age 50–75 years) undergoing unilateral primary end-stage total knee arthroplasty will be randomly divided into group A or group B. Group A will be treated with one dose of TXA (1 g; intravenous injection 3 hours postsurgery) and group B with three doses (1 g; intravenous injection at 3, 6 and 12 hours postsurgery) after surgery. The primary outcomes will be evaluated with blood loss, maximum haemoglobin drop and transfusion rate. The secondary outcomes will be evaluated with knee function and complications.

Ethics and dissemination

The Shanghai Guanghua Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine Ethics Committee approved in this study in July 2019. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants. Results of the trial will be published in the Dryad and repository in a peer-reviewed journal. Additionally, deidentified data collected and analysed for this study will be available for review from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR1900025013.

Keywords: tranexamic acid, total knee arthroplasty, perioperative blood management, knee, paediatric orthopaedics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study in China to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a perioperative multiple-dose regimen of tranexamic acid (TXA) during total knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The bias of this study was reduced dramatically by the extensive study design, which included proper randomisation, allocation concealment and objective indications.

If multiple-dose TXA after surgery can reduce postoperative blood loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis without adverse events, this medication regimen may reduce the occurrence of postoperative anaemia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The short follow-up time may be insufficient in fully assessing the risk of complications in a multiple-dose regimen of TXA during total knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) may be accompanied by haematological diseases such as anaemia.1 The overall prevalence of RA is 0.5%–1% in Europe and North America, 0.31% in France, 0.32%–0.38% in China and 0.02%–0.047% in Japan.2 3 Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is effective in treating flexion contractures and maintaining the stability of knees effected by RA.4 About 0.005% of patients with RA receive TKA, a rate that has gradually decreased over the past decades. However, surgery remains the first choice for articular deformity and pain, despite the fact that disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics agents can manage synovitis-related symptoms in patients with RA.5 Haemorrhage is a major perioperative complication of TKA.6 Excessive blood loss should be treated with an allogeneic blood transfusion, but this has adverse effects such as immune complications, prolong hospitalisation time and increased infection rate.7 8 Haemoglobin (Hb) has a negative correlation with disease activity in RA.9 Therefore, we believe that perioperative blood loss management is needed for patients with RA.

Accounting for approximately 50% of the total blood loss (TBL), hidden blood loss (HBL) is the blood lost as infiltrates into the tissue intraoperatively and postoperatively. This blood resides in the knee joint cavity before being haemolysed.10 HBL often leads to the joint swelling, postoperative inflammation and pain.11 12

Use of a surgical tourniquet can reduce intraoperative bleeding,13 provide a clear view during the surgery and facilitate the connection between the cement, bone and joint prostheses.14 However, after the release of the tourniquet, local tissue may be damaged by ischaemic reperfusion injury, and the fibrinolytic system may be activated.15 16 As a consequence, peripheral blood circulation can be accelerated, plasma fibrinolysis enhanced and postoperative HBL increased.15 Therefore, reducing the dissolution of fibrin can reduce postoperative HBL.17

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic lysine derivative that competitively inhibits the binding between plasminogen and fibrin, prevents the activation of plasminogen and protects fibrin from degradation and dissolution by plasmin. TXA was initially used in obstetric and gynaecological surgery, and its use was then gradually replicated in other surgeries to reduce bleeding and blood transfusion rates.18 19 The Clinical Randomisation of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Haemorrhage trial has demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of TXA in reducing blood loss.20 A large amount of literature has reported that TXA can significantly reduce peri-TKA blood loss.21,22–25 Currently, TXA is recommended for perioperative management of blood loss during TKA.26 However, its efficacy and safety in patients with RA undergoing TKA has rarely been reported.27 TXA can be administered through oral intake, a single large-dose intravenous injection, an intra-articular injection, joint cavity irrigation, postoperative drainage tube injection or through a combination of these methods.25 28–30 There is no consensus on the optimal dosage and timing of perioperative TXA administration for TKA.18 31 32 Studies have shown that fibrinolysis peaks at 6 hours and continues for approximately 18 hours after TKAs that were performed with tourniquets.33 The half-life of TXA in the plasma is 2 hours, and its concentration peaks at 1 hour after injection.34 Thus, we suspect that a single dose of TXA may not be sufficient to exert an antifibrinolytic effect. There are also studies suggesting that, for patients with osteoarthritis, higher doses (within the normal range) during the perioperative period can increase the efficacy of TXA.35 36 The purpose of this clinical trial is to verify the effectiveness and safety of multiple doses of TXA in reducing perioperative blood loss in patients with RA treated with TKA, in order to determine a new strategy for management of perioperative blood loss during TKA.

Methods and analysis

Study context

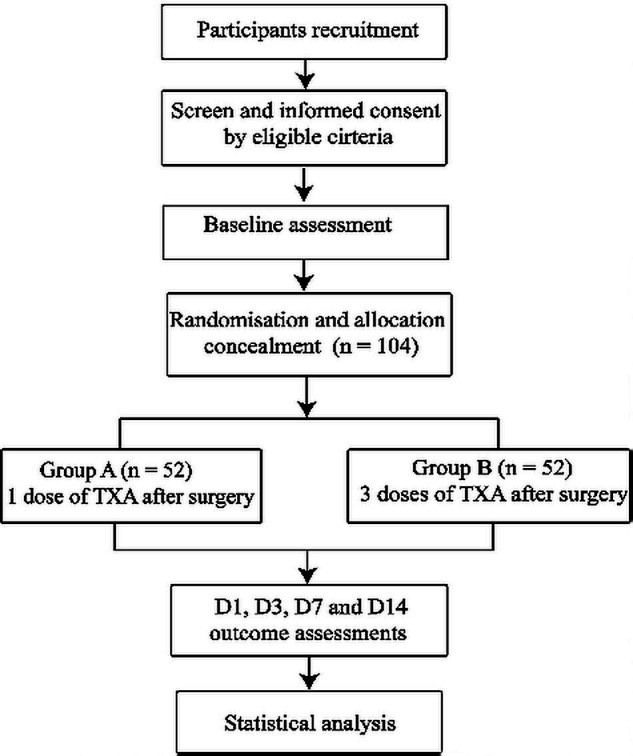

This clinical trial was initiated on 1 September 2019 in the wards of Guanghua Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Shanghai, China). The annual number of TKA cases performed in RA patients with RA was about 300 in 2018. Eleven investigators will be involved in this study including two senior orthopaedic surgeons (L-BX and W-TZ) with 20 years of clinical experience, six orthopaedic physicians (C-XG, JZ, JX, S-TS, Y-HM and SZ), two data collectors who are also statisticians (B-XK and HX) and a nurse (Xi-Rui Xu). Informed consent will be obtained from all patients. The perioperative enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) blood management programme and the trial flow chart are shown in box 1 and figure 1. The schedule is shown in table 1.

Box 1. Enhanced recovery after surgery blood management.

Preoperative

Treatment of haemorrhagic primary disease.

Nutritional guidance, balanced diet.

Iron application.

Rhu-Epo application.

Intraoperative

Minimally invasive surgery.

Tourniquet optimisation.

Controlled buck.

Autologous blood return.

Use of tranexamic acid.

Postoperative

Reduce bleeding (pressure dressing of wounds, prevent stress ulcers).

Nutritional support, iron supplementation, use of Rhu-Epo.

Rhu-Epo, recombinant human erythropoietin.

Figure 1.

The study flow diagram, including participants recruitment, eligibility, screening, randomisation, allocation concealment and outcome assessments. D1, the frist day after surgery; D3, the third day after surgery; D7, the seventh day after surgery; D14, the 14th day after surgery; TXA, tranexamic acid.

Table 1.

The schedule of trial enrolment, interventions and assessments

| Outcome assessment | |||||

| Pre-OP | D1 | D3 | D7 | D14 | |

| Enrolment | ● | ||||

| Assessment of eligibility | ● | ||||

| Randomisation | ● | ||||

| Group A Post-OP 1 dose of TXA |

● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Group B Post-OP 3 doses of TXA |

● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| HBL | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Haemoglobin level | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Inflammatory index | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Inflammatory factor | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Coagulation index | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Swelling rate | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| DVT | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| PE | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Postoperative complications and adverse events | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

D1, the first day after surgery; D3, the third day after surgery; D7, the seventh day after surgery; D14, the 14th day after surgery; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; HBL, hidden blood loss; OP, operative; PE, pulmonary embolism; TXA, tranexamic acid.

Sample size calculation

This study uses a completely randomised trial design. Multiple sample sizes will evaluated by a review of previously conducted clinical research.25 The primary outcome will be measured with the amount of HBL, dependent on TXA therapy. The overall SD is σ=250, and the allowable error estimate is δ=200. These values were estimated using the statistical formula Predicting an estimated drop-out rate of 10%, 104 subjects will be required to yield a power of 90% with a significance level of 0.05.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Patients will be randomly assigned to two groups (1:1 ratio). This will be done by assigning each patient a number from 1 to 104. SPSS V.25.0 (IBM) will be used to generate a random sequence containing the numbers 1–104, dividing these numbers in two groups. These group lists will be placed in an opaque envelope and put into a computer by encryption. The group data will be saved by the statistician. Only the nurse will be allowed to check the enrolment and give the corresponding treatment.

Single-blinded design

Only the nurse will be allowed to know the patients’ enrolment and give them the corresponding treatment. The outcome evaluators will objectively record the patients’ test results.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria have been set in accordance with the ‘American Rheumatism Association criteria for RA’37 and the 2010 ‘ American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for RA’.38 The eligibility criteria are as follows: (1) The patient must have been diagnosed with RA in Stage III or IV according to the Kellgren-Lawrence classification39; (2) The patient must be 50–75 years old; (3) The patient must be willing to undergo the unilateral primary TKA; (4) The patient must receive perioperative anti-fibrinolytic TXA therapy and (5) The patient must show normal blood-clotting function and must not have preoperative anaemia.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Other types of arthritis (such as primary arthritis, post-traumatic osteoarthritis, gouty osteoarthritis, haemophilic osteoarthritis and tuberculous arthritis); (2) Bilateral knee arthroplasty (patients with RA); (3) Severe cardiovascular disease (such as myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, angina pectoris and cardiac failure) or cerebrovascular disease (such as cerebral infarction and cerebral haemorrhage) and (4) Prolonged use of oral anticoagulant drugs (such as aspirin, warfarin and clopidogrel).

Elimination criteria

The elimination criteria are as follows: (1) Acquired colour vision disorder; (2) Active intravascular coagulation patients and (3) A history of seizures.

Termination criteria

The termination criteria are as follows: (1) Shock; (2) Allergic symptoms such as itching and a rash; (3) Digestive disorders such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and diarrhoea after medication; (4) Symptoms such as reactive dermatitis, dizziness, hypotension, drowsiness, headache; convulsions, and visual impairment and (5) Adverse events such as intracranial thrombosis and intracranial haemorrhage after medication.

Perioperative antirheumatic treatment

Methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine will be used during the perioperative period. Leflunomide will be discontinued 1 week before surgery. Use of other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs will be discontinued 2 days before surgery, and restarted 1–2 days after gastrointestinal function recovery. The use of newer biological agents such as tumour necrosis factor alpha will be discontinued 4–5 half-lives before surgery and restarted after wound healing and infection elimination.40 41

Surgery and anaesthesia

Surgery will be performed by two senior surgeons (L-BX and W-TZ). During each surgery, a standard midline incision will be followed by a medial parapatellar capsular incision to expose the knee joint. A tourniquet will be used for all patients at a pressure of 200–250 mm Hg. The operations will be conducted under general anaesthesia and blood pressure will be controlled within a range of 80–100/60–70 mm Hg by anaesthetists throughout the surgical procedure. During the operation, conventional anti-infective, combined analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anticoagulation treatment and other symptomatic treatments will be administered according to the ‘Chinese Hip and TKA Surgery Perioperative Anti-fibrinolytic Drug Sequential Anticoagulant Application Programme Expert Consensus’.26 Ten min prior to skin incision, 1 g of TXA + 100 mL of intravenous-saline will be administered, and then 1.5 g of TXA + 50 mL articular-injection saline will be administered postoperatively into the sutured joint cavity. Group A and B will then receive additional TXA therapy according to the treatment regime devised for each group.

TXA is produced by Hunan Dongting Pharmaceutical, and used according to the second edition of the 2015 Chinese Pharmacopoeia and Drug Supplement Application Approval (2013B02016), YBH07372010; the National Drug Standard approval number is H43020565.

Study interventions

Group A: 1 g of TXA + 100 mL of physiological saline will be administered intravenously 3 hours after the operation. Group B: 1 g of TXA + 100 mL of physiological saline will be administered intravenously 3, 6 and 12 hours after the operation.

Pain management and rehabilitation

A cocktail injection will be given during the operation, and 0.2 g of oral celecoxib will be given after surgery for analgesia. After the anaesthesia, the maximum angles of flexion and extension of the ankle will be maintained for 6 s, and the foot will then be allowed to relax for 5 s. This exercise will be performed on both limbs in order to ensure the quadriceps contractions are equal. On the first postoperative day, the patients will be encouraged to exercise using straight-leg-raises, supine-knee-flexion and knee flexion and extension in sitting. Machine-assisted exercises, such as continuous passive motion, will begin on the third day after surgery.

Antibiotics

For perioperative infection prophylaxis, cefazolin (40 mg) will be administered 30 min before surgery and 24–48 hours after surgery.42

Prevention of lower extremity venous thrombosis

Six hours after the surgery, enoxaparin sodium injections (60 mg) will be initiated and continued daily for 14 days to prevent formation of a deep vein thrombosis.26

Outcome measures

Complete blood count, hepatic function, renal function and coagulation function will be routinely tested before surgery. Complete blood count, inflammatory index, inflammatory factor and coagulation index will be tested on the 1st, 3rd, 7th and 14th days after surgery. All the blood tests will be assessed in our hospital (Department of Clinical Laboratory of Guanghua Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine) by an inspector who is not involved in this clinical trial.

Primary outcome measures

Blood loss, haemoglobin level and transfusion rate

Blood loss is calculated according to the formulae by Nadle et al43 and Gross44: Patient’s blood volume (PBV)=K1 × height3 (m3) + K2 × weight (kg) + K3. Male: K1=0.3669, K2=0.03219, K3=0.6041; Female: K1=0.3561, K2=0.03308, K3=0.1833. TBL=PBV × (Hctpre − Hctpost) / Hctave. Hctpre=the initial preoperative Hct level; Hctpost=the lowest Hct post-operative; Hctave=the average of the Hctpre and Hctpost. The amount of intraoperative blood loss=the total volume of fluid in the negative pressure drain − the volume of normal saline. HBL volume=TBL vol − intraoperative blood loss volume.

The maximum haemoglobin decline will be defined as the difference between the preoperative Hb level and the minimal Hb level drawn postoperatively during the hospitalisation and prior to any blood transfusion. The transfusion rate for patients requiring a transfusion will be determined postoperatively during the inpatient hospital stay.

Secondary outcome measures

Knee function and swelling

Knee function will be measured using the American Knee Society Score 1 day before surgery and on the 3rd, 7th and 14th days after surgery. A trained researcher will educate all patients until they fully understand how to assess their knee function using the questionnaires. The degree of swelling is defined as the postoperative circumference of the upper tibia divided by the preoperative circumference of the upper tibia.

Adverse event measures

Potential adverse events include deep vein thrombosis (clinical manifestations: acute onset, affected limb swelling, sever pain, or significant tenderness at the femoral triangle or/and leg) and pulmonary embolism (clinical manifestations: cough, chest tightness, palpitations, haemoptysis, shortness of breath, dizziness, shock, cyanosis, increased respiratory rate, arteriovenous filling or pulsation, etc). Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism will be diagnosed by Doppler ultrasound and CT, respectively. The wound healing process and complications (wound bleeding, haematoma, wound infection and deep infection) will be observed and recorded in the patient’s case report forms (CRFs) during the hospitalisation and follow-ups.

Adverse event treatment

Adverse events during the follow-up period will be recorded in the CRFs, and their relevance to drug use will be evaluated. All the adverse events will be classified in accordance with the five-level scoring systems (5.0) of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Serious adverse events are defined as those that may cause cancer, teratogenicity, death, permanent damage to organ function, permanent or significant disability and prolonged hospital stay. In the case of adverse events occurring, the researcher should immediately take appropriate measures and report these events to the hospital and ethics committees within 24 hours.

Data management

Data on the CRFs will be put into the computer by two independent trained research assistants with a double-entry method. The hospital’s independent investigators will check the data periodically.

Statistical analysis

(1) Descriptive analysis on the characteristics of the study participants; (2) Balance analysis on the baseline values in groups; (3) Comparison of the balance of primary outcomes between groups and (4) Comparison of secondary outcomes and safety between groups. The total rate of adverse events in the two groups will be tested by the bidirectional disordered R*C list X2 test. The association between the incidence of adverse events and the dose of TXA use will be described.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public will not be involved in the development of the research question or in the design of the study. Patients will receive oral and written information about this trial, pertaining to the benefits, risks and discomforts that they may experience during the study. Further, the burden of the intervention will be assessed by patients themselves. Dissemination of the general results (no personal data) will be made available on reasonable request.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been granted by the Shanghai Guanghua Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine Ethics Committee. Written inform consent will be obtained from all participants or their authorised agents before initiation of the study. All TXA treatments will be free. Personal data of participants will be kept strictly confidential and obtained from appropriate authors on reasonable request. Results of the trial will be published on the Dryad website and in a peer-reviewed journal.

Discussion

Controlling blood loss can facilitate the recovery from TKA surgery. Previous clinical studies have shown that high doses of TXA can reduce blood loss after TKA in patients with osteoarthritis.25 45 46 It has been reported that an intravenous infusion of TXA, combined with intra-articular injection may be the optimal bleeding-control scheme.47 48 Previous studies have shown that knee joint swelling after TKA is associated with HBL in the joint cavity. TXA can reduce postoperative HBL, thereby relieving the swelling around the joint.11 Given that plasminogen activators play an important role in RA-involved inflammation, the dissolution of fibrin will trigger an inflammatory response.49 Therefore, we suspect that multiple doses of TXA in the perioperative period may exert an auxiliary anti-inflammatory effect.

Enhanced recovery after surgery is strongly advocated, and the management of perioperative blood loss is an essential component. The RA patients with RA aged 50–80 years undergoing TKA have a lower risk of requiring a revision, and are likely to obtain higher knee function and present with fewer complications.50 51 In order to reduce bias caused by a wide age range, patients aged 50–75 will be selected. This study will provide new evidence for managing perioperative blood loss in TKA in Chinese patients with RA if the results indicate that the administration of the additional three doses of TXA therapy after surgery is beneficial over a single dose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants who volunteered to participate in this research.

Footnotes

B-XK and HX contributed equally.

Contributors: B-XK, HX and L-BX conceived the study while B-XK and HX drafted the study protocol. The study protocol was designed by C-XG, SZ, JZ, JX, S-TS, Y-HM and W-TZ. All authors approved the final manuscript of this study protocol.

Funding: This work will be supported by the Foundation of Health and Family planning Commission of Shanghai (Grant No. ZY (2018–2020)-FWTX-6023).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Goyal L, Shah PJ, Yadav RN, et al. Anaemia in newly diagnosed patients of rheumatoid arthritis and its correlation with disease activity. J Assoc Physicians India 2018;66:26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minichiello E, Semerano L, Boissier M-C. Time trends in the incidence, prevalence, and severity of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine 2016;83:625–30. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shichikawa K, Inoue K, Hirota S, et al. Changes in the incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Kamitonda, Wakayama, Japan, 1965-1996. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:751–6. 10.1136/ard.58.12.751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan D, Yang J, Pei F. Total knee arthroplasty treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with severe versus moderate flexion contracture. J Orthop Surg Res 2013;8:41. 10.1186/1749-799X-8-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Louie GH, Ward MM. Changes in the rates of joint surgery among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in California, 1983-2007. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:868–71. 10.1136/ard.2009.112474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ker K, Roberts I. Tranexamic acid for surgical bleeding. BMJ 2014;349:g4934. 10.1136/bmj.g4934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman J, Luke K, Escobar M, et al. Experience of a network of transfusion coordinators for blood conservation (Ontario Transfusion Coordinators [ONTraC]). Transfusion 2008;48:237–50. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormack PL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the treatment of hyperfibrinolysis. Drugs 2012;72:585–617. 10.2165/11209070-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padjen I, Öhler L, Studenic P, et al. Clinical meaning and implications of serum hemoglobin levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47:193–8. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sehat KR, Evans R, Newman JH. How much blood is really lost in total knee arthroplasty?. correct blood loss management should take hidden loss into account. Knee 2000;7:151–5. 10.1016/s0968-0160(00)00047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishida K, Tsumura N, Kitagawa A, et al. Intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid reduces not only blood loss but also knee joint swelling after total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2011;35:1639–45. 10.1007/s00264-010-1205-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu X, Zhang X, Chen Y, et al. Hidden blood loss after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:1100–5. 10.1016/j.arth.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarwala R, Dorr LD, Gilbert PK, et al. Tourniquet use during cementation only during total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:169–74. 10.1007/s11999-013-3124-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arthur JR, Spangehl MJ. Tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2019;32:719–29. 10.1055/s-0039-1681035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnettler T, Papillon N, Rees H. Use of a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty causes a paradoxical increase in total blood loss. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:1331–6. 10.2106/JBJS.16.00750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aglietti P, Baldini A, Vena LM, et al. Effect of tourniquet use on activation of coagulation in total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;85:169–77. 10.1097/00003086-200002000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benoni G, Lethagen S, Fredin H. The effect of tranexamic acid on local and plasma fibrinolysis during total knee arthroplasty. Thromb Res 1997;85:195–206. 10.1016/S0049-3848(97)00004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennings JD, Solarz MK, Haydel C. Application of tranexamic acid in trauma and orthopedic surgery. Orthop Clin North Am 2016;47:137–43. 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Napolitano LM, Cohen MJ, Cotton BA, et al. Tranexamic acid in trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1575–86. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318292cc54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CRASH-2 trial collaborators, Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:23–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adravanti P, Di Salvo E, Calafiore G, et al. A prospective, randomized, comparative study of intravenous alone and combined intravenous and intraarticular administration of tranexamic acid in primary total knee replacement. Arthroplast Today 2018;4:85–8. 10.1016/j.artd.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakash J, Seon J-K, Park YJ, et al. A randomized control trial to evaluate the effectiveness of intravenous, intra-articular and topical wash regimes of tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg 2017;25:230949901769352–7. 10.1177/2309499017693529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao Z, Yue B, Wang Y, et al. A comparative, retrospective study of peri-articular and intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid for the management of postoperative blood loss after total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:1–8. 10.1186/s12891-016-1293-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jansen JA, Lameijer JRC, Snoeker BAM. Combined intravenous, topical and oral tranexamic acid administration in total knee replacement: evaluation of safety in patients with previous thromboembolism and effect on hemoglobin level and transfusion rate. Knee 2017;24:1206–12. 10.1016/j.knee.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lei Y, Xie J, Xu B, et al. The efficacy and safety of multiple-dose intravenous tranexamic acid on blood loss following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Int Orthop 2017;41:2053–9. 10.1007/s00264-017-3519-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhen Y, Zongke Z, Fuxing P, et al. Chinese hip and total knee arthroplasty surgery perioperative Anti-fibrinolytic drug sequential anticoagulant application programme expert consensus. Chin J Bone Joint Surg 2015;8:281–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie J, Hu Q, Huang Z, et al. Comparison of three routes of administration of tranexamic acid in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty: analysis of a national database. Thromb Res 2019;173:96–101. 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yue C, Kang P, Yang P, et al. Topical application of tranexamic acid in primary total hip arthroplasty: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:2452–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Yang C, Huang X, et al. Tranexamic acid reduces occult blood loss, blood transfusion, and improves recovery of knee function after total knee arthroplasty: a comparative study. J Knee Surg 2018;31:239–46. 10.1055/s-0037-1602248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Lv Y-M, Ding P-J, et al. The reduction in blood loss with intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid in unilateral total knee arthroplasty without operative drains: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015;25:135–9. 10.1007/s00590-014-1461-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young B, Moondi P. A questionnaire-based survey investigating the current use of tranexamic acid in traumatic haemorrhage and elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JRSM Open 2014;5:204253331351694. 10.1177/2042533313516949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cid J, Lozano M. Tranexamic acid reduces allogeneic red cell transfusions in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion 2005;45:1302–7. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanié A, Bellamy L, Rhayem Y, et al. Duration of postoperative fibrinolysis after total hip or knee replacement: a laboratory follow-up study. Thromb Res 2013;131:e6–11. 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt BJ. The current place of tranexamic acid in the management of bleeding. Anaesthesia 2015;70:50–e18. 10.1111/anae.12910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demos HA, Lin ZX, Barfield WR, et al. Process improvement project using tranexamic acid is cost-effective in reducing blood loss and transfusions after total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:2375–80. 10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang Y, Wen Y, Li W, et al. The efficacy and safety of multiple doses of oral tranexamic acid on blood loss, inflammatory and fibrinolysis response following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg 2019;65:45–51. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silman AJ. The 1987 revised American rheumatism association criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1988;27:341–3. 10.1093/rheumatology/27.5.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Britsemmer K, Ursum J, Gerritsen M, et al. Validation of the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: slight improvement over the 1987 ACR criteria. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1468–70. 10.1136/ard.2010.148619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND. Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474:1886–93. 10.1007/s11999-016-4732-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause ML, Matteson EL. Perioperative management of the patient with rheumatoid arthritis. World J Orthop 2014;5:283–91. 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thorsness RJ, Hammert WC. Perioperative management of rheumatoid medications. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:1928–31. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JT. Commentary on the “guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999”. Am J Infect Control 1999;27:96 10.1016/S0196-6553(99)70094-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadler SB, Hidalgo JH, Bloch T. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 1962;51:224–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gross JB. Estimating allowable blood loss: corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology 1983;58:277–80. 10.1097/00000542-198303000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park JH, Choi SW, Shin EH, et al. The optimal protocol to reduce blood loss and blood transfusion after unilateral total knee replacement: low-dose IA-TXA plus 30-min drain clamping versus drainage clamping for the first 3 H without IA-TXA. J Orthop Surg 2017;25:230949901773162–7. 10.1177/2309499017731626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Voorn VMA, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, van der Hout A, et al. The effectiveness of a de-implementation strategy to reduce low-value blood management techniques in primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a pragmatic cluster-randomized controlled trial. Implement Sci 2017;12:72. 10.1186/s13012-017-0601-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mi B, Liu G, Lv H, et al. Is combined use of intravenous and intraarticular tranexamic acid superior to intravenous or intraarticular tranexamic acid alone in total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Orthop Surg Res 2017;12:61. 10.1186/s13018-017-0559-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iseki T, Tsukada S, Wakui M, et al. Intravenous tranexamic acid only versus combined intravenous and intra-articular tranexamic acid for perioperative blood loss in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2018;28:1397–402. 10.1007/s00590-018-2210-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, Ny A, Leonardsson G, et al. The plasminogen activator/plasmin system is essential for development of the joint inflammatory phase of collagen type II-induced arthritis. Am J Pathol 2005;166:783–92. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62299-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goh GS-H, Liow MHL, Bin Abd Razak HR, et al. Patient-reported outcomes, quality of life, and satisfaction rates in young patients aged 50 years or younger after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:419–25. 10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyd JA, Gradisar IM. Total knee arthroplasty after knee arthroscopy in patients older than 50 years. Orthopedics 2016;39:e1041–4. 10.3928/01477447-20160719-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.