Abstract

Objective

It has been established that most patients prescribed opioids after minor surgery have tablets left over, better understanding the variation in opioid prescribing and variation in dosage of the prescription could guide efforts to reduce prescribing. This study describes the state-level variation in opioid prescribing after a knee arthroscopy among opioid-naïve patients.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Commercial insurance claims data.

Participants

98 623 individual across the USA with commercial insurance who were opioid-naïve and had a knee arthroscopy between 2015 and 2019.

Exposure

Patients who filled an opioid prescription within 3 days of a knee arthroscopy.

Outcome measures

Opioid prescriptions were measured as a pharmacy claim for filling an opioid within 3 days of a knee arthroscopy. We measured the patient and state-level opioid prescribing rate, tablet count, morphine milligram equivalent dose per prescription and risk-adjusted predicted opioid quantity.

Results

Overall, 72% of patients filled an opioid prescription with a median tablet count of 40 and median morphine milligram equivalent of 250. Patients with an invasive procedure (27.9% vs 22.4%; p<0.001), higher education level (p<0.001) and fewer comorbidities (0.9 vs 1.2, p<0.001) had higher rates of opioid prescribing. The prescribing rate in the highest state, Nebraska (85%), was double the prescribing rate in the lowest state, South Dakota (40%). Comparing the casemix adjusted expected prescribing rate to the observed prescribing rate displayed that 18 states had observed prescribing rates that were higher than their expected prescribing rates.

Conclusion

Wide variation in the likelihood of receiving a prescription, depending on state of residence, was observed. The dosages prescribed were high and have been associated with transition to long-term use. These findings suggest that there is substantial opportunity for the development of guidelines to reduce variability in opioid prescribing for this common ambulatory procedure.

Keywords: health policy, knee, public health, pain management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is among the first to demonstrate the degree of state-level variation in opioid prescribing rates for a common minor surgical procedure.

The work provides a clear view of the degree to which prescribing rates can be reduced given that surgical approaches and pain response is not expected to dramatically vary by state.

Another strength is the adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics to account for differences in casemix across states.

Our study is a claims-based study does not capture prescriptions that were made but not filled by patients or prescriptions that were paid out of pocket.

Demographic and clinical characteristics we could assess were limited to the claims data.

Introduction

Between 1999 and 2016, opioid prescribing quadrupled to over 259 million prescriptions per year. Opioid-related deaths are the leading cause of unintentional death in the USA responsible for at least 47 000 fatalities in 2018.1 For many procedures, opioid analgesics have become the default standard of care for postoperative pain management and are the leading exposure of patients to opioid prescriptions, particularly among the opioid-naïve, even after low-risk surgical procedures.2–5 This can be problematic because a single prescription and higher dosage prescriptions have been associated with prolonged opioid use.6–14 Furthermore, 50%–70% of opioid tablets prescribed are never taken posing the risk of misuse and diversion.15

Surgical societies have called for more judicious opioid prescribing and have promoted the concept of ‘opioid stewardship’ in postoperative pain.16–18 As with long-standing efforts to promote antibiotic stewardship, the first step in establishing postoperative opioid stewardship initiatives is to establish baseline use, duration and variation by procedure and indication.19 Even though the national levels of prescribing are well documented, limited attention has been given to the regional variation in opioid prescribing for opioid-naïve patients after common outpatient surgeries.4 20–22 Orthopaedic arthroscopic procedures account for two of the top three most common outpatient surgical procedures performed in the USA, yet there is a dearth of literature benchmarking opioid prescribing rates and dosages for these procedures.23–25 Knee arthroscopy is the most common outpatient orthopaedic procedure in the USA, with approximately 1 million procedures per year.26 27 A new report from National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine highlight knee arthroscopy as a priority indication for establishing evidence-based opioid prescribing guidelines.28 Establishing the baseline variation in opioid prescribing after knee arthroscopy is a critical knowledge gap to fill to establish quality improvement targets. Prescribing targets are essential in reducing prescribing with a large potential public health impact given the volume of this procedure and current lack of consensus for this procedure on postoperative opioid use.

The goal of our study was to describe the patient and state-level variation in postoperative opioid prescribing rates and dosages for opioid-naïve patients after a knee arthroscopy in the USA. Our investigation focused on the prescribing practices among the commercially insured, a relatively unexplored group of individuals in terms of opioid prescribing, but the one with the highest risk of opioid use and abuse.7 We hypothesised that there would be substantial variation in the state and patient-level prescribing rates and dosages, even after accounting for patient characteristics.

Methods

We used the Clinformatics Data Mart Database (OptumInsight) from January 2015 to June 2019, which comprises commercial insurance claims from a large national US private health insurer covering 7.5 million lives annually represented in every state. We defined an index knee arthroscopy encounter as the earliest visit in which a beneficiary had a knee arthroscopy provider medical claim.29

We focused our analysis on opioid-naïve patients and excluded any patients who filled an opioid prescription within the 6 months preceding the index surgery date. We also excluded patients who did not receive the knee arthroscopy in the outpatient hospital or ambulatory surgical centre setting to retain a more homogeneous sample. Patients who did not have medical claims for the surgery and the operational facility charge on the same day or the day after were also excluded to mitigate concerns regarding the day of the actual surgery. Lastly, we excluded patients who had multiple knee arthroscopy surgeries to reduce the confounding effect of reoperation on the probability that opioid prescriptions were associated with additional surgeries.

We collected patient demographic information on age, gender, education, household income, ethnicity and the state where the surgery was performed. We identified the patients’ Elixhauser comorbidities, as well as diagnosis codes for drug abuse, alcohol abuse, depression and psychoses from any medical claims filed in the previous 6 months. We also used Current Procedural Technology codes to classify knee arthroscopy procedures based on involvement of bone (invasive, such as anterior cruciate ligament repair) versus soft tissue only (non-invasive, such as simple knee arthroscopy) (See online supplementary appendix for a list of included Current Procedural Terminology codes).

bmjopen-2019-035126supp001.pdf (606.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient-relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Definition of opioid prescription

We identified prescription claims based on the pharmacy claims and identified opioids according to National Drug Codes (excluding methadone and non-tablet formulations) filled within 3 days of the index visit. See online supplementary appendix for a description of included opioids. We excluded opioids primarily used for treatment of opioid use disorder. We attributed a filled prescription within 3 days of the surgery to the physician by extracting the encrypted National Provider Identifier (NPI) on the pharmacy claim. We also used the pharmacy claim to identify the drug name, strength, number of tablets, and days supplied. We calculate morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per tablet based on conversion factors available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which were used to calculate the total MME per prescription.

Outcomes

The goal of the study was to describe the prescription rate, defined as the per cent of opioid-naïve patients who filled an opioid prescription within 3 days of the knee arthroscopy, and the regional variation of the prescription rate across the US states. Secondary outcomes of interest were the average quantity (in tablets) per prescription, and the total MME of the prescription. To assess the geographic variation, we aggregated all opioid outcomes to the state level, resulting in average outcomes for each state. We also analysed the primary and secondary outcomes by procedure type (invasive vs non-invasive). Lastly, we used age, race, ethnicity, level of education, comorbidities, procedure and state information to predict the probability of receiving an opioid prescription within 3 days using a logistic regression model to understand how observed versus predicted prescribing patterns vary after adjusting for patient characteristics. We then follow previously established methods by Delgado et al and estimated observed-to-expected state-level prescribing ratios with 95% CIs, with values over 1 indicating patients in that state that were more likely to fill opioids than expected, and less than 1 indicating patients in states that were less likely to fill opioids than expected.14

Results

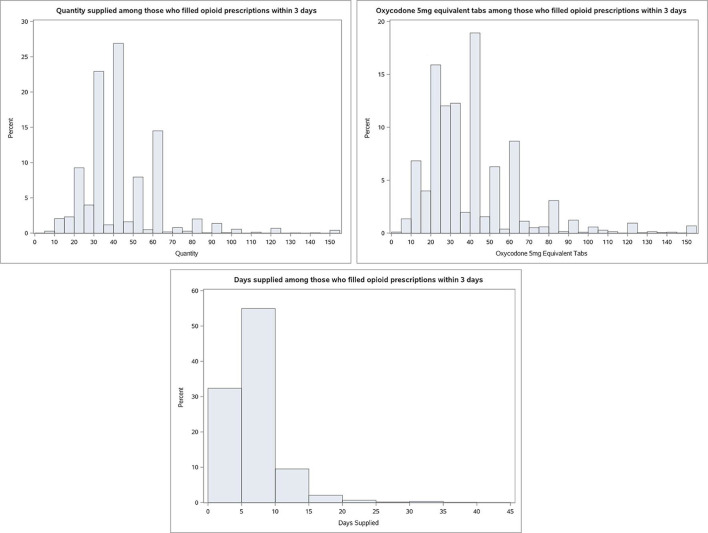

During the study period, 225 277 patients underwent knee arthroscopy. After exclusions, 98 623 opioid-naïve patients were available for the final analysis (figure 1) with 26 011 patients undergoing an invasive arthroscopic procedure involving drilling or cutting of bone and 72 612 patients who had a non-invasive arthroscopic procedure in which only soft tissue work was performed. Figure 1 displays that 72% of opioid-naïve patients filled a prescription. The prescription rate was only slightly higher for invasive vs non-invasive procedures (76% vs 71%). Compared with patients who did not fill an opioid prescription in table 1, patients with an initial opioid prescription were more likely to be younger (46.7 years of age vs 52.3 years of age, p<0.001) and more predominately female (54.4% vs 53.0%, p<0.001). Those who filled an opioid prescription were more likely to be higher educated (have a bachelor’s degree or more 23.4% vs 21.6%, p<0.001), were more likely to have household incomes above US$100 000 (41.3% vs 38.4%, p<0.001), were slightly more likely to be white (73.2% vs 71.9%, p<0.001) and were more likely to have an invasive procedure relative to a non-invasive procedure (27.9% vs 22.4%, p<0.001). In terms of comorbidities, those who received an opioid prescription were more likely to have fewer comorbidities than those who did not receive an opioid (0.9 vs 1.2 Elixhauser Index score, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of Sample. It displays the flow chart from the full sample that leads to our final sample after sample exclusion restrictions.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics stratified by filled prescription within 3 days of surgery

| Patient characteristics | Opioid-naïve | Opioid-naïve and opioid prescription (n=71.190) | P value |

| (n=27 433) | |||

| Age (mean, SD) | 52.28 (18.82 | 46.71 (17.77) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 12 894 (47.0%) | 32 445 (45.6%) | <0.001 |

| Female | 14 537 (53.0%) | 38 741 (54.4%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (0.0%) | 4 (0.0%) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | ||

| No high school degree | 46 (0.2%) | 120 (0.2%) | |

| High school degree | 5208 (19.0%) | 12 934 (18.2%) | |

| Some college | 14 011 (51.1%) | 36 685 (51.5%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 5915 (21.6%) | 16 680 (23.4%) | |

| Unknown | 87 (0.3%) | 223 (0.3%) | |

| Procedure type | |||

| Invasive | 6135 (22.4%) | 19 876 (27.9%) | <0.001 |

| Household income | <0.001 | ||

| Less than 40 k | 2699 (9.8%) | 6536 (9.2%) | |

| 40–49 k | 1077 (3.9%) | 2766 (3.9%) | |

| 50–59 k | 1367 (5.0%) | 3186 (4.5%) | |

| 60–74 k | 2155 (7.9%) | 5104 (7.2%) | |

| 75–99 k | 3874 (14.1%) | 9487 (13.3%) | |

| 100 k and more | 10 528 (38.4%) | 29 415 (41.3%) | |

| Unknown | 2166 (13.0%) | 4548 (14.3%) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Asian | 559 (2.0%) | 1738 (2.4%) | |

| Black | 1650 (6.0%) | 4303 (6.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 2306 (8.4%) | 5797 (8.1%) | |

| White | 19 714 (71.9%) | 52 106 (73.2%) | |

| Unknown | 3204 (11.7%) | 7246 (10.2%) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Mean no of elixhauser comorbidities (SD) | 1.20 (1.59) | 0.91 (1.35) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 8708 (31.7%) | 17 165 (24.1%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (%) | 161(0.6%) | 278 (0.4%) | <0.001 |

| Depression (%) | 2181 (8.0%) | 5268 (7.4%) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes (%) | 1199 (4.4%) | 2285 (3.2%) | <0.001 |

| Psychoses (%) | 65 (0.2%) | 117 (0.2%) | 0.009 |

| Alcohol abuse (%) | 187 (0.7%) | 436 (0.6%) | 0.888 |

| Drug abuse (%) | 207 (0.8%) | 300 (0.4%) | <0.001 |

| Median no tablets (IQR) | – | 40 (30–50) | |

| Days supplied, median (IQR) | – | 5 (4–7) | |

| MME/prescription, median (IQR) | – | 250 (150–375) |

MME, morphine milligram equivalent.

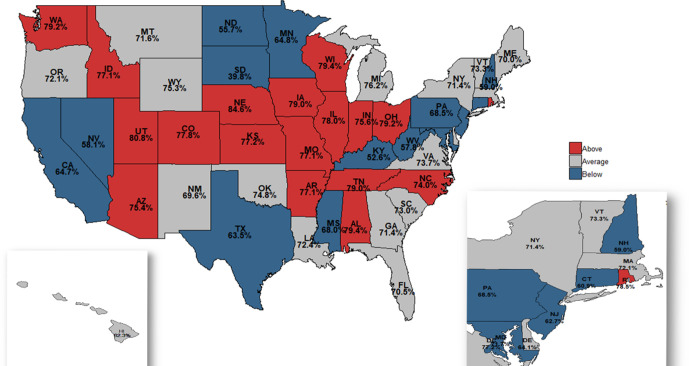

Patient-level variation in dosages of opioid prescriptions

We observed wide variation in opioid prescribing in terms of the number of tablets, the day’s supply and total MME for the 72% of patients who filled a prescription within 3 days of the index surgery (figure 2). The median prescription was for 40 tablets (IQR 30–50), 250 MME (150-375), with a median duration of 5 days (IQR 4–7) (online supplementary appendix table 1). At the 90th percentile, patients who filled a prescritpion with more than 60 tablets experienced a prescription duration of at least 13 days and an MME of more than 733 MME.

Figure 2.

Details on the prescriptions filled within 3 days of the index date. It displays the distribution of the opioid fill for members who filled an opioid within 3 days of the index date for the quantity, MME and days supply. MME, morphine milligram equivalent.

Translating the dosage to MME per day suggests that the median patient received an average daily dosage of 50 MME, which is the same as the 50 MME level identified as increasing the risks for overdose death by the Center for Disease Control (CDC).30 In terms of differences in prescribing by procedure type, invasive procedures resulted in a slightly higher average quantity, MME and day’s supply than non-invasive procedures, however, these findings are not-statistically different from each other (online supplementary appendix table 1 and figure 1).

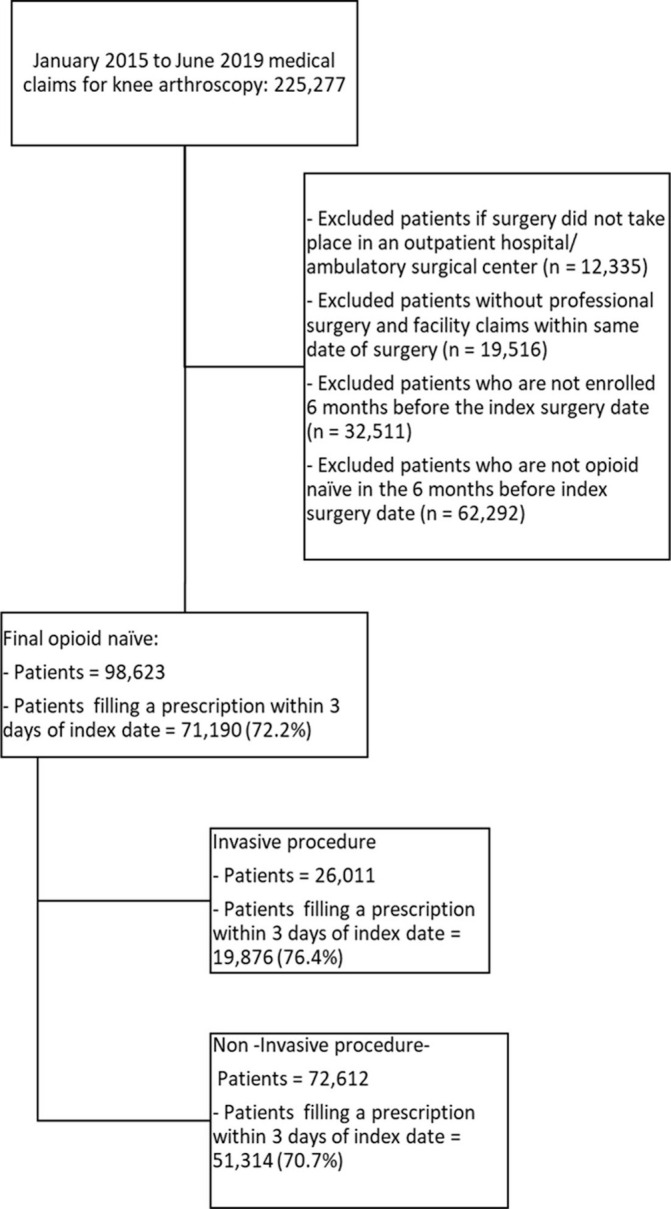

State-level variation in opioid prescribing rates and dosages

We also observed wide variation in the state level in the proportion of patients who filled an opioid prescription within 3 days of the index date was also observed (figure 3). The observed prescription fill rate ranged from 40% in South Dakota to 85% in Nebraska (see also online supplementary appendix table 2). Figure 3 also highlights states that had statistically different observed prescribing rates either above (shown in red) or below the expected prescribing rate (blue) adjusted for casemix and covariates. Several states had observed prescribing rates well below the expected rate. North Dakota, South Dakota, Nevada, Kentucky and West Virginia had prescribing rates that were between 20% and 40% lower than expected based on patient characteristics. In contrast, Alabama, Rhode Island, Utah and Nebraska exhibited prescribing rates that were 10% higher than the expected rates. Overall, 18 states had prescribing rates that were higher than expected based on patient casemix (online supplementary appendix figures 2-4). These results highlight significant variation in terms of prescribing even after adjusting for patient characteristics.

Figure 3.

Observed to expected opioid prescribing rate. State-level variation in the opioid prescribing rate for knee arthroscopies among patients who were opioid-naïve. The median state-level prescribing rate during these years was 72%. The observed prescribed rate is displayed within each state. States with higher-than-expected prescribing rates based on covariates are highlighted in red and those with lower-than-expected prescribing rates are shown in blue. Expected prescribing rate was adjusted for casemix with age, sex, procedure type, race, ethnicity, education, household income, comorbidities and year, using multivariate logistic regression.

While we found variation in observed to expected opioid prescription dosages at the state level, it was less dramatic than the variation in the prescription rate. The median tablet count for all states was 40 (IQR=36–42 tablets). Tablet count per prescription varied from 24.1 in Vermont to 44.9 in Oklahoma. The median state level MME was 277 MME (IQR=245–300 MME) per prescription and varied from 157 MME in Vermont to 371 MME in Oklahoma (online supplementary appendix table 2).

Discussion

In a US sample of over 98 000 opioid-naive commercially insured patients who underwent an outpatient knee arthroscopy between 2015 and 2019, we found high rates of opioid prescribing and large variation in patient and state-level opioid prescribing rates, even after adjusting for key patient characteristics. Over 72% of patients filled an opioid prescription within 3 days of the surgery date, where the median patient received a 5-day supply, a median tablet count of 40 tablets and a dosage of 250 MME. There was twofold state-level variation prescribing between the highest prescribing rate (85% in Nebraska) compared with the state with the lowest prescribing rate (40% in South Dakota), and this variation persisted even after adjustment for patient characteristics.

The significant variation in prescribing rates and dosages indicates there could be ample room to reduce variation in prescribing as we do not expect the pathophysiology of pain to be markedly different across state lines for these common outpatient procedures. The observed dosage suggests that the median patient received an average daily dosage of 50 MME, which is equal to the 50 MME level identified as increasing the risks for overdose death by the CDC.30 Nevertheless, these prescribing levels may pose adverse health risks when alternative strategies may be equally effective for many patients.31 32 Over 5 million MME could have been prevented from being distributed if the MME level would not have exceeded the median total MME dosage in each year (online supplementary appendix table 3). A growing general consensus outlines that prescriptions should not be written for more than 50 MME per day and no more than 6 days (ie, 300 MME).30 Nevertheless, 36% of patients who filled a prescription received a dosage that is higher than the recommended threshold.

Our results expand previous work by examining more broadly the prescribing patterns after minor surgeries among opioid-naïve patients who are commercially insured. Using data from a national commercial insurer allowed us to investigate the prescribing rates among a younger population that has a documented higher risk of opioid dependence and misuse.7 33 34 To date, the existing evidence has predominately focused on inpatient procedures among single institutions or has focused on specific groups such as the military population or the elderly.5 13 35

In terms of the existing literature evaluating opioid prescribing after surgical procedures, our results imply similarly high rates of prescribing compared with those reported for inpatient procedures. Opioid prescribing after orthopaedic surgery is very common and orthopaedic surgery has one of the highest frequency of opioid claims among Medicare patients.3 Our results mirror prior studies suggesting that post-operative opioids continue to be prescribed at high amounts independent of type of procedure and expected pain intensity and duration.5 This is an opportunity for improvement given that excessive opioid prescribing among the opioid-naïve is associated with the risk of long-term opioid use22 and left over tablets can be diverted and misused.33 36 37

Our findings demonstrate that postoperative knee arthroscopy pain management relies heavily on opioids, while more conservative treatments may be sufficient, especially for less severe cases, though few guidelines exist.30 31 The National Academies of the Sciences, Engineering and Medicine highlighted knee arthroscopy as a high priority procedure that would benefit from evidence-based guidelines for postoperative opioid prescribing.28 Orthopaedic-specific opioid prescribing guidelines could have a significant impact on reducing excessive variation in prescribing and reducing risks of long-term use and misuse.2 3 Health systems could implement lower electronic default opioid dosage based on these guidelines. These strategy has been shown to reduce opioid prescribing while still preserving clinician autonomy.38 39

Future research should aim at understanding how many opioid tablets are actually needed to control pain after knee arthroscopy and to optimise and guide prescribing levels that minimise the opportunity for left over opioids and subsequent opioid diversion. Studies are also needed to identify whether there is a dosage threshold level that is associated with prolonged use and other long-term unintended health outcomes and consequences on overall patient care needs.24 25

From a policy research perspective, it is critical to understand how differences in state opioid prescribing limits, policies on mandated Prescription Drug Monitoring Programme use, guidelines and culture contribute to the state-level variation in prescribing rates and dosages and associated downstream and local health outcomes. Insights gleaned from lower prescribing states could be applied to help reduce variation in higher prescribing states with the potential to safely reduce excessive prescribing.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we were only able to measure filled prescriptions (not prescribed prescriptions) obtained within the population that generated an insurance bill, and cannot speak to the number of consumed tablets, or measure opioid prescriptions obtained through other channels. We potentially underestimated the prescribing rate, as unfilled prescriptions and filled prescription paid out of pocket were not captured. Second, unmeasured differences between patients, such as access to different provider networks, copayments and coinsurance may have contributed to the observable variation in opioid prescribing. Third, limitations in data do not allow us to decisively attribute patients to physicians. Excluding patients without a knee arthroscopy and an opioid prescription within a 3-day window should improve patient–physician match. Fourth, we cannot make any statements regarding how state policies may have already reduced prescribing, such as prescribing guidelines or how effective policies may be.40–42 Lastly, our results are only generalisable to the general commercially insured opioid-naïve population who received a knee arthroscopy.

Conclusions

Our findings using US data from 2015 to 2019 suggest there is still wide patient and state-level variation in postoperative opioid prescribing for opioid-naïve patients undergoing knee arthroscopy. This suggests substantial opportunities to reduce practice variation with the development and implementation of knee arthroscopy-specific opioid prescribing guidelines. Development of such guidelines is urgently needed because of the potential health consequences associated with the current dosages being prescribed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correction notice: The article has been corrected since it was published online. The author's name M Kit Delgado has been updated.

Contributors: BU and MKD conceived the study. YH acquired the data. BU and MKD conducted the analysis. MKD supervised the analysis. All authors (BU, YH, BS and MKD) interpreted the results. BU and MKD drafted the manuscript. All authors (BU, YH, BS and MKD) contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. BU takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Funding: 'Research reported in this publication was supported by pilot grant funding from the National Institute On Drug Abuse (P30DA040500). KD was also supported by a contract from Food and Drug Administration (HHSF223201810209C), a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD090272001), and The Abramson Family Foundation Fund for Acute Care and Injury Prevention Research.'

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data are not available due to data-sharing restrictions. Data can be purchased from Optum (please visit the website for more information: https://www.optum.com/solutions/data-analytics.html). Statistical code available on request.

References

- 1.NIH National Institute on drug abuse, 2020. Available: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates [Accessed May 29, 2020].

- 2.Ringwalt C, Gugelmann H, Garrettson M, et al. . Differential prescribing of opioid analgesics according to physician specialty for Medicaid patients with chronic noncancer pain diagnoses. Pain Res Manag 2014;19:179–85. 10.1155/2014/857952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen JH, Humphreys K, Shah NH, et al. . Distribution of opioids by different types of Medicare prescribers. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:259–61. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, et al. . Trends in opioid Analgesic–Prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:409–13. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scully RE, Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W, et al. . Defining optimal length of opioid pain medication prescription after common surgical procedures. JAMA Surg 2018;153:37–43. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah A. Characteristics of initial prescription episodes and likelihood of long-term opioid Use—United states, 2006–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2017;66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Russo JE, et al. . The role of opioid prescription in incident opioid abuse and dependence among individuals with chronic noncancer pain: the role of opioid prescription. Clin J Pain 2014;30:557. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med 2017;376:663–73. 10.1056/NEJMsa1610524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Hallvik SE, Hildebran C, et al. . Association between initial opioid prescribing patterns and subsequent long-term use among opioid-naïve patients: a statewide retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:21–7. 10.1007/s11606-016-3810-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozet I, Nishio I, Robbertze R, et al. . Prolonged opioid use after knee arthroscopy in military veterans. Anesth Analg 2014;119:454–9. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffery MM, Hooten WM, Hess EP, et al. . Opioid prescribing for Opioid-Naive patients in emergency departments and other settings: characteristics of prescriptions and association with long-term use. Ann Emerg Med 2018;71:326–36. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soneji N, Clarke HA, Ko DT, et al. . Risks of developing persistent opioid use after major surgery. JAMA Surg 2016;151:1083–4. 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang X, Orton M, Feng R, et al. . Chronic opioid usage in surgical patients in a large academic center. Ann Surg 2017;265:722–7. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delgado MK, Huang Y, Meisel Z, et al. . National Variation in Opioid Prescribing and Risk of Prolonged Use for Opioid-Naive Patients Treated in the Emergency Department for Ankle Sprains. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72:389–400. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, et al. . Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery. JAMA Surg 2017;152:1066–71. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.bulletin.facs.org American College of surgeons Bulletin. 102, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varley PR, Zuckerbraun BS. Opioid stewardship and the surgeon. JAMA Surg 2018;153:e174875. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trasolini NA, McKnight BM, Dorr LD. The opioid crisis and the orthopedic surgeon. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:3379–82. 10.1016/j.arth.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier TP, Lantz E, Heyliger A, et al. . Internet-Based institutional antimicrobial stewardship program resources in leading US academic medical centers. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:445–6. 10.1093/cid/cit705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis LH, Stoddard J, Radeva JI, et al. . Geographic variation in the prescription of schedule II opioid analgesics among outpatients in the United States. Health Serv Res 2006;41:837–55. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00511.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izrael D. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the U.S. J Pain 2012;13:988–96. 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, et al. . Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1286–93. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, et al. . Long-Term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:425–30. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, et al. . Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g1251. 10.1136/bmj.g1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. . New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg 2017;152:e170504. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steiner CA, Karaca Z, Moore BJ, et al. . Surgeries in Hospital-Based Ambulatory Surgery and Hospital Inpatient Settings, 2014: Statistical Brief# 223, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan JP, et al. . Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of national surveys of ambulatory surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:994–1000. 10.2106/JBJS.I.01618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine Framing opioid prescribing guidelines for acute pain: developing the evidence. National Academies Press, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Optum.com Clinformatics data Mart, 2018. Available: https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum/resources/productSheets/Clinformatics_for_Data_Mart.pdf [Accessed 28 Nov 2018].

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage, 2017. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdfViewinArticleGoogleScholar[Accessed 17 Jan 2018].

- 31.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. . Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American pain Society, the American Society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists' Committee on regional anesthesia, executive Committee, and administrative Council. J Pain 2016;17:131–57. 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegmann KT, Weiss MS, Bowden K, et al. . ACOEM practice guidelines: opioids for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, and postoperative pain. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:e143–59. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. . Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA 2008;300:2613–20. 10.1001/jama.2008.802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, et al. . Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among Veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain 2007;129:355–62. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, et al. . Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg 2017;265:709–14. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, et al. . Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2017;152:1066–71. 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maughan BC, Hersh EV, Shofer FS, et al. . Unused opioid analgesics and drug disposal following outpatient dental surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;168:328–34. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delgado MK, Shofer FS, Patel MS, et al. . Association between electronic medical record implementation of default opioid prescription quantities and prescribing behavior in two emergency departments. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:409–11. 10.1007/s11606-017-4286-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiu AS, Jean RA, Hoag JR, et al. . Association of lowering default pill counts in electronic medical record systems with postoperative opioid prescribing. JAMA Surg 2018;153:1012. 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiner SG, Baker O, Poon SJ, et al. . The effect of opioid prescribing guidelines on prescriptions by emergency physicians in Ohio. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:799–808. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden RM, et al. . Vital Signs: Demographic and Substance Use Trends Among Heroin Users - United States, 2002-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:719. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. . Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:697–704. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035126supp001.pdf (606.8KB, pdf)