Abstract

Objective

Though estimates of longevity are available by states, age, sex and place of residence in India, disaggregated estimates by social and economic groups are limited. This study estimates the life expectancy at birth and premature mortality by caste, religion and regions of India.

Design

This study primarily used cross-sectional data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–2016 and the Sample Registration System (SRS), 2011–2015. The NFHS-4 is the largest ever demographic and health survey covering 601 509 households and 811 808 individuals across all states and union territories in India.

Measures

The abridged life table is constructed to estimate the life expectancy at birth, adult mortality (45q15) and premature mortality (70q0) by caste, religion and region.

Results

Life expectancy at birth was estimated at 63.1 years (95% CI 62.60 -63.64) for scheduled castes (SC), 64.0 years (95% CI 63.25 - 64.88) for scheduled tribes (ST), 65.1 years (95% CI 64.69 - 65.42) for other backward classes (OBC) and 68.0 years (95% CI 67.44 - 68.45) for others. The life expectancy at birth was higher among o Christians 68.1 years (95% CI 66.44 - 69.60) than Muslims 66.0 years (95% CI 65.29 - 66.54) and Hindus 65.0 years (95% CI 64.74 -65.22). Life expectancy at birth was higher among females than among males across social groups in India. Premature mortality was higher among SC (0.382), followed by ST (0.381), OBC (0.344) and others (0.301). The regional variation in life expectancy by age and sex is large.

Conclusion

In India, social and religious differentials in life expectancy by sex are modest and need to be investigated among poor and rich within these groups. Premature mortality and adult mortality are also high across social and religious groups.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology, adult intensive & critical care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first ever study that provides estimates of life expectancy, by caste, religion and region in India.

It provides estimates of premature and adult mortality across social groups and regions in India.

Disease burden, disability and cause of premature mortality have not been explored in this study.

State-specific estimates of life expectancy and premature mortality have not been estimated due to inadequate sample size.

Estimates of mortality and longevity are not linked to socioeconomic status in India.

Introduction

Life expectancy at birth is one of the most frequently used summary measures of health. It is used to quantify the health dimension of the human development index.1 Globally, life expectancy at birth is converging among and within countries.2–4 Countries are also converging in infant mortality rate, under-five mortality rate and utilisation of basic health services.5–7 Despite higher life expectancy at birth of females than male, findings from a large number of studies in developing countries suggest that females are disadvantaged in health and healthcare utilisation.8–13 Though life expectancy at birth has been rising in almost all societies, mortality differences exist within, as well as between, population subgroups within national and regional boundaries.14–23 Regional disparity in mortality is associated with socioeconomic well-being and access to healthcare.24–26 Conventionally, those with an urban residence and the economically and socially better off tend to have lower mortality and higher longevity.27–30

India, with a population of 1.35 billion in 2018, is experiencing significant improvement in health indicators. Life expectancy at birth has increased from 58.7 years in 1990 to 68.30 years in 2015 (Registrar General of India(RGI)). The state variations in life expectancy have been narrowing down over the years. Although India has witnessed spectacular improvement in mortality, the changes in mortality conditions across the states have been different.26 There is strong north–south gradient across the states, with great variations in the level and the pace of mortality reduction over time.31–33 For instance, life expectancy was higher in Kerala than in Uttar Pradesh in India34–37; adult mortality and premature deaths were also high.33 The national and state average in life expectancy conceal large variation among states and social groups in India.

Health, education and employment in India vary by social and economic groups in India. Caste and religion are often used as key social variables and given priority in national and state policies. The population of India is classified into four caste groups, namely: scheduled castes (SC), scheduled tribes (ST), other backward classes (OBC) and others. The ST population, accounting for 8.6% of the total population, is the most deprived followed by SCs. A large number of studies have examined the caste differentials in health and healthcare in India and its states and found that the SC and ST population have poor health.38–40 However, studies suggest that the increasing socioeconomic inequality over the years has led to poor health outcomes among population subgroups in the country.41–47

The Sample Registration System (SRS) provides regular estimates of life expectancy at birth and age-specific death rate (ASDR) for major states, by sex and place of residence. However, such estimates are not available for social groups such as caste and religion and by economic groups. To our knowledge, there are few studies that provided the estimates of life expectancy by social group/economic group. Mohanty and Ram48 stimated life expectancy at birth among the social groups using National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-2 and NFHS-3 data and found that life expectancy at birth is similar among the poor across caste groups. Recently, Asaria et al47 have provided estimates of life expectancy at birth across wealth quintiles using NFHS-4 data and found that life expectancy at birth among the poorest wealth quintile was 65.1 years compared with 72.7 years in the richest wealth quintile.

Patel explains that SC women may be inequitably served by maternal health services and, in some cases, even face specific discrimination. Low health status is observed among poor, female, rural and specific minority groups of ST and SC.49–52 In comparison with the general castes, lower caste (OBC and SC/ST) women were more likely to experience discrimination in rural western India.53 Lower caste women reported a higher prevalence of poorer health than women of higher castes.38 54 At age 60 years, life expectancy, active life expectancy and inactive life expectancy estimates were significantly higher, by 2.3, 1.9 and 0.4 years, for older persons in the general castes group versus those in the SC/ST/OBC groups, respectively.46 55 Many studies support the finding that life expectancy was lower in the central region than in other regions.40 56

The national average in longevity conceals large variations across population subgroups and by socioeconomic characteristics. This is the first-ever study that estimates the life expectancy and mortality pattern by caste, religion, region and sex in India.

Data sources

Data from the NFHS-4, 2015–2016 and the SRS, 2011–2015 have been used. The NFHS are cross-sectional study based on large-scale, multiround surveys, conducted in a representative sample of households throughout India. The first round of NFHS was conducted in 1992–1993 and the fourth round in 2015–2016. The NFHS-4 covered 601 509 households and 811 808 individuals. The NFHS provides reliable estimates of fertility, child mortality, family planning, child nutritional status and childhood morbidity for the country. With regard to mortality, NFHS 1, 2 and 3 were intended to provide reliable estimates of infant and child mortality. However, in NFHS-4, an attempt was made to capture overall mortality, and data were collected at the national and district levels. It has the distinction of the largest ever population-based health survey in the country.

Questions were asked on the death of any members of the household in a 3-year reference period. A total of 74 945 deaths was recorded during the survey. Along with death records, data on sex, place of residence, caste, religion and household’s assets and amenities were collected. Caste data were collected for SC, ST, OBC and others. Generally, the STs are considered to be socially and economically poorer, followed by SCs and OBCs. Many central and state government welfare schemes have been specifically designed for the welfare of the population. Similarly, data on religion were collected in seven groups. These are Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, other religion and religion not stated. We have combined Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, other religion and religion not stated groups owing to sample size constraints. The ASDR from SRS is used to compare the mortality rate across age groups.

Methods

The SRS data do not provide information on death by socioeconomic status (SES). The advantages of using NFHS data is the use of its death statistics by socioeconomic characteristics. In the NFHS-4, 0.6% (479) of 74 945 deaths were found missing for one or more SES. The missing information on SES for age at death were adjusted.

The following steps were used in adjusting missing cases, computing the ASDR, life expectancy at birth, adult mortality (45q15) and premature mortality (70q0) by caste, religion and region.

Adjustment of missing death cases: The cases with missing information on SES for age at death were inflated by 100/100 -x for each age group.47

A total of 479 cases was found missing for some basic variables like age, sex and other SES characteristics. We have distributed 479 cases equally in each age group.

Estimation of ASDR:The annual ASDR was estimated as the data were collected in 3-year reference period.

Estimation of life expectancy using abridged life table: life expectancy at birth was computed using age-specific death and midyear population from the NFHS-4 life table approach. The 95% CI of estimates are provided.57

The abridged life table is constructed to estimate life expectancy at birth, adult mortality (45q15) and premature mortality (70q0) by caste, religion and region. Premature mortality is defined as any death under 70 years of age. The mathematical form of premature mortality (70q0) = and mortality in working age (45q15) =.58

Finally, the ASDR was used to compute life expectancy at birth by sex, caste, religion and region using the Chiang method. In the Chiang method, the nax is estimated by the average number of years lived in the x to x+n age interval by those dying in the interval.58–60

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved. The paper uses secondary data available for public use.

Results

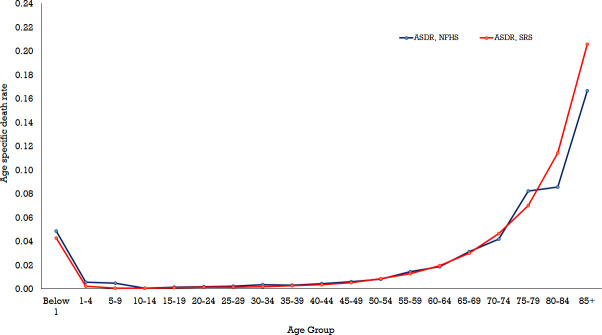

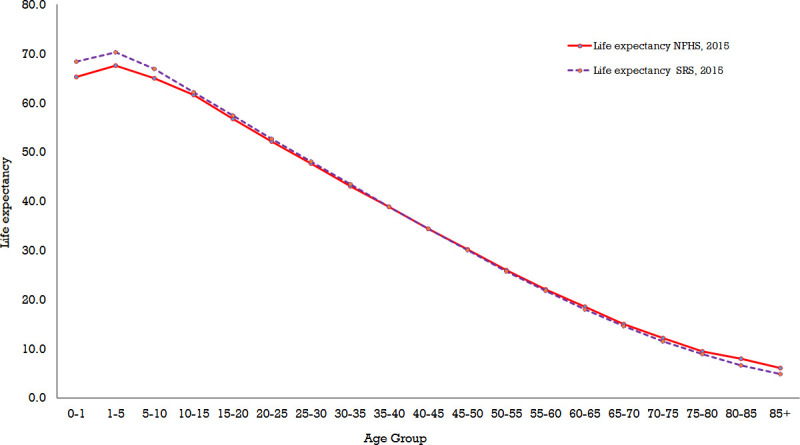

Figure 1 plots the ASDR from SRS and NFHS in a 5-year age group. The SRS estimates of life expectancy at birth in India was 68.3 years and that from NFHS-4 is 65.3 years. In general, the ASDRs is close from both the sources and the ASDRs overlap in a large number of age groups. Table 1 presents the numerical value of ASDR from SRS and NFHS by a 5-year age group. Figure 2 presents the life expectancy at various ages. Results suggest that life expectancy varies with different social characteristics; caste, religion and region in India.

Figure 1.

Age-specific death rate (ASDR) from NFHS-4 and SRS, 2011–2015, in India. NFHS, National Family Health Survey; SRS, Sample Registration System.

Table 1.

ASDR by 5-year age group and estimated life expectancy from NFHS-4 and SRS in India, 2015–2016

| Age group | ASDR_NFHS | ASDR_SRS | Life expectancy NFHS_2015 with CIs | Life expectancy SRS_2015 |

| 0–1 | 0.0485 | 0.0429 | 65.3 (65.08 to 65.54) | 68.3 |

| 1–5 | 0.0055 | 0.0022 | 67.5 (67.34 to 67.75) | 70.3 |

| 5–10 | 0.0049 | 0.0008 | 65.0 (64.79 to 65.20) | 66.9 |

| 10–15 | 0.0008 | 0.0007 | 61.5 (61.35 to 61.74) | 62.2 |

| 15–20 | 0.0014 | 0.0011 | 56.8 (56.59 to 56.94) | 57.4 |

| 20–25 | 0.0018 | 0.0015 | 52.2 (51.98 to 52.34) | 52.7 |

| 25–30 | 0.0021 | 0.0017 | 47.6 (47.44 to 47.79) | 48.1 |

| 30–35 | 0.0036 | 0.0020 | 43.1 (42.93 to 43.28) | 43.5 |

| 35–40 | 0.0032 | 0.0027 | 38.8 (38.68 to 39.01) | 38.9 |

| 40–45 | 0.0045 | 0.0038 | 34.4 (34.24 to 34.57) | 34.4 |

| 45–50 | 0.0060 | 0.0054 | 30.1 (29.98 to 30.31) | 30.0 |

| 50–55 | 0.0083 | 0.0086 | 26.0 (25.83 to 26.15) | 25.7 |

| 55–60 | 0.0147 | 0.0127 | 22.0 (21.84 to 22.15) | 21.7 |

| 60–65 | 0.0188 | 0.0196 | 18.5 (18.32 to 18.63) | 18.0 |

| 65–70 | 0.0311 | 0.0303 | 15.1 (14.91 to 15.20) | 14.6 |

| 70–75 | 0.0418 | 0.0465 | 12.2 (12.04 to 12.32) | 11.5 |

| 75–80 | 0.0821 | 0.0700 | 9.4 (9.29 to 9.58) | 8.9 |

| 80–85 | 0.0856 | 0.1142 | 8.0 (7.89 to 8.13) | 6.6 |

| 85+ | 0.1664 | 0.2058 | 6.0 (6.01 to 6.01) | 4.9 |

ASDR, age-specific death rate; NFHS, National Family Health Survey; SRS, Sample Registration System.

Figure 2.

Estimated life expectancy at birth from NFHS-4, 2015–2016 and SRS, 2011–2015, in India. NFHS, National Family Health Survey; SRS, Sample Registration System.

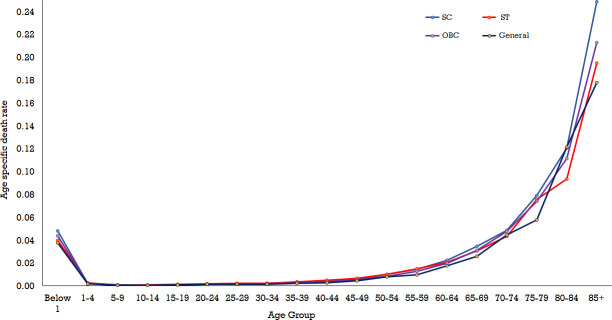

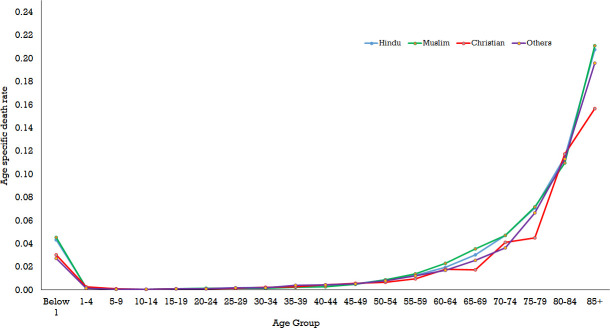

Figure 3 summarises the estimated ASDR by caste in India. The ASDR was higher among SCs (0.055) followed by OBCs (0.050), STs (0.045) and then others (0.043) at below age 1 year. Similarly, at later ages, the curve shows a skewed pattern in each category. Figure 4 presents the ASDR by religion. The ASDR was higher among Muslims (0.051) than among others (0.031) for age below 1 year. Among population aged 50 years, the ASDR was higher for Hindus than for Christian. However, at later ages, the ASDR was higher among Muslims followed by Hindus, others and Christians in India.

Figure 3.

Age-specific death rate across caste groups in India, 2015–2016. OBC, other backward classes; SC, scheduled castes; ST, scheduled tribes.

Figure 4.

Age-specific death rate by religion in India, 2015–2016.

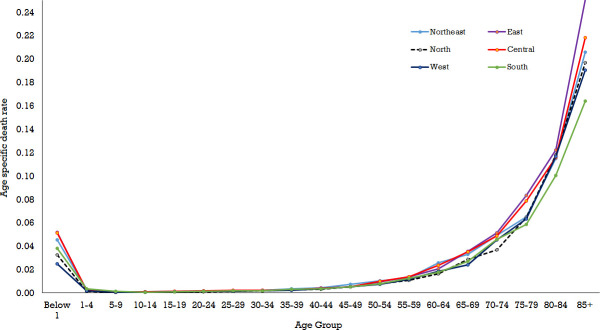

Figure 5 shows that the ASDR for those below 1 year, was higher in the Eastern region (0.059) followed by the Central region (0.025). The death rate among children aged 1–9 years was higher in the Southern than in the Northern regions (0.009 vs 0.003). The death rate was almost similar between age groups 10–34. The death rate for population in the age group 65–69 was higher in the Eastern region than in the Western region (0.036 vs 0.025). The variations were visible at age below one and in the 1–4 age group and showed a gap among the population of age-groups 60–85.

Figure 5.

Age-specific death rate across regions in India, 2015–2016.

The life expectancy at birth varies from 4 years across different caste groups in India (table 2). The life expectancy at birth was estimated at 63.1 years (95% CI 62.60 - 63.64) for SC, 64.0 years (95% CI 63.25 - 64.88) for STs, 65.1 years (95% CI 64.69 - 65.42) for OBCs and 68.0 years (95% CI 67.44 - 68.45) for others (see online supplementary appendix table 1). Females had a higher life expectancy at birth compared with males, and this gap remains consistent across all the social groups. However, this gap decreases at the onset of elderly age (60 years) and ranges from 0.8 to 2.5 years across social groups. The life expectancy at age 60 years was 17 years for SCs, 18.2 years for OBCs, 18.6 years for STs and 19.5 years for Others. These findings are consistent with those of other studies.8 9 Women had a higher life expectancy than men across different caste categories in India.

Table 2.

Life expectancy by caste and sex in India, 2015–2016

| Age Interval | SC | ST | OBC | Others | ||||||||

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| Below 1 | 63.13 | 60.32 | 66.31 | 64.02 | 60.53 | 67.89 | 65.06 | 62.88 | 67.47 | 67.94 | 66.09 | 69.95 |

| 1 | 65.65 | 63.13 | 68.48 | 65.96 | 62.90 | 69.34 | 67.35 | 65.25 | 69.64 | 69.89 | 68.11 | 71.81 |

| 5 | 63.12 | 60.59 | 65.95 | 63.84 | 60.98 | 67.01 | 64.82 | 62.81 | 67.00 | 67.07 | 65.26 | 69.01 |

| 10 | 59.70 | 57.18 | 62.52 | 60.04 | 57.18 | 63.19 | 61.43 | 59.41 | 63.62 | 63.59 | 61.89 | 65.41 |

| 15 | 54.96 | 52.43 | 57.78 | 55.35 | 52.52 | 58.47 | 56.65 | 54.62 | 58.87 | 58.77 | 57.06 | 60.58 |

| 20 | 50.39 | 47.90 | 53.17 | 50.83 | 47.98 | 53.98 | 52.03 | 49.98 | 54.26 | 54.10 | 52.37 | 55.96 |

| 25 | 45.87 | 43.42 | 48.61 | 46.44 | 43.58 | 49.60 | 47.48 | 45.46 | 49.69 | 49.53 | 47.77 | 51.41 |

| 30 | 41.45 | 39.08 | 44.11 | 42.06 | 39.29 | 45.14 | 42.96 | 41.02 | 45.07 | 44.92 | 43.25 | 46.71 |

| 35 | 37.25 | 35.02 | 39.75 | 37.96 | 35.38 | 40.80 | 38.70 | 36.90 | 40.68 | 40.48 | 38.98 | 42.10 |

| 40 | 32.87 | 30.83 | 35.17 | 33.72 | 31.36 | 36.30 | 34.27 | 32.64 | 36.07 | 35.96 | 34.62 | 37.40 |

| 45 | 28.76 | 26.98 | 30.77 | 29.65 | 27.42 | 32.08 | 29.97 | 28.53 | 31.55 | 31.55 | 30.36 | 32.82 |

| 50 | 24.66 | 23.04 | 26.47 | 25.69 | 23.75 | 27.77 | 25.78 | 24.56 | 27.13 | 27.31 | 26.30 | 28.39 |

| 55 | 20.76 | 19.45 | 22.26 | 21.88 | 20.30 | 23.63 | 21.74 | 20.72 | 22.91 | 23.30 | 22.73 | 23.97 |

| 60 | 17.39 | 16.27 | 18.69 | 18.62 | 17.44 | 19.93 | 18.24 | 17.44 | 19.15 | 19.51 | 19.16 | 19.96 |

| 65 | 14.09 | 13.20 | 15.10 | 15.29 | 14.44 | 16.21 | 14.79 | 14.14 | 15.53 | 16.01 | 15.82 | 16.29 |

| 70 | 11.37 | 10.72 | 12.12 | 12.47 | 11.69 | 13.28 | 11.95 | 11.44 | 12.52 | 12.93 | 12.87 | 13.08 |

| 75 | 8.55 | 8.00 | 9.15 | 9.63 | 9.04 | 10.19 | 9.22 | 8.85 | 9.61 | 10.27 | 10.34 | 10.28 |

| 80 | 7.22 | 6.66 | 7.78 | 8.70 | 8.28 | 9.09 | 7.95 | 7.51 | 8.39 | 8.44 | 8.66 | 8.34 |

| 85+ | 4.97 | 4.47 | 5.43 | 6.35 | 6.32 | 6.38 | 5.82 | 5.46 | 6.15 | 6.95 | 7.97 | 6.28 |

OBC, other backward classes; SC, scheduled castes; ST, scheduled tribes.

bmjopen-2019-035392supp001.pdf (125.1KB, pdf)

Table 3 summarises religious differentials in life expectancy. It suggests that the life expectancy at birth was higher among others with 68.6 years (95% CI 67.38 - 69.80) compared with Christian with 68.1 years (95% CI 66.44 - 69.60) and Muslims with 65.9 years (95% CI 65.29 - 66.54) than India with 65.0 years (95% CI 64.74 - 65.22) (see online supplementary appendix table 2). The gap in life expectancy between male and female was highest among Christians (8 years), followed by others (6 years), Hindus (5 years) and Muslims (3 years). Female life expectancy at birth was highest among Christians (72.1 years) followed by others (71.5 years) and Hindus (67.7 years), but it was lowest among Muslims (67.6). The sex differential in life expectancy at age 20 was higher among Christians followed by Hindus, others and Muslims.

Table 3.

Life expectancy by religion and sex in India, 2015–2016

| Age interval | Hindu | Muslim | Christian | Others | ||||||||

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| Below 1 | 64.98 | 62.51 | 67.71 | 65.89 | 64.39 | 67.55 | 68.07 | 64.33 | 72.06 | 68.59 | 65.89 | 71.53 |

| 1 | 67.22 | 64.94 | 69.71 | 68.32 | 66.84 | 69.92 | 69.41 | 65.80 | 73.24 | 69.74 | 67.39 | 72.28 |

| 5 | 64.74 | 62.54 | 67.14 | 65.54 | 63.92 | 67.29 | 67.19 | 64.11 | 70.40 | 66.60 | 64.46 | 68.91 |

| 10 | 61.39 | 59.19 | 63.78 | 61.61 | 60.03 | 63.33 | 64.40 | 61.88 | 66.96 | 62.53 | 60.30 | 64.94 |

| 15 | 56.63 | 54.42 | 59.03 | 56.82 | 55.20 | 58.58 | 59.60 | 57.18 | 62.05 | 57.64 | 55.41 | 60.05 |

| 20 | 52.03 | 49.81 | 54.45 | 52.15 | 50.59 | 53.84 | 54.97 | 52.50 | 57.48 | 52.91 | 50.75 | 55.22 |

| 25 | 47.51 | 45.30 | 49.91 | 47.60 | 46.03 | 49.30 | 50.26 | 47.74 | 52.83 | 48.27 | 46.23 | 50.44 |

| 30 | 43.01 | 40.90 | 45.32 | 42.96 | 41.45 | 44.62 | 45.66 | 43.28 | 48.09 | 43.77 | 41.74 | 45.94 |

| 35 | 38.77 | 36.83 | 40.89 | 38.51 | 37.07 | 40.09 | 41.45 | 39.10 | 43.83 | 39.44 | 37.72 | 41.25 |

| 40 | 34.35 | 32.59 | 36.28 | 34.01 | 32.66 | 35.50 | 37.02 | 34.94 | 39.14 | 35.33 | 33.58 | 37.16 |

| 45 | 30.10 | 28.55 | 31.79 | 29.55 | 28.26 | 30.98 | 32.91 | 31.19 | 34.64 | 31.22 | 29.79 | 32.71 |

| 50 | 25.95 | 24.60 | 27.42 | 25.32 | 24.18 | 26.58 | 28.90 | 27.47 | 30.35 | 27.11 | 25.81 | 28.44 |

| 55 | 21.97 | 20.93 | 23.14 | 21.31 | 20.33 | 22.42 | 24.75 | 23.85 | 25.72 | 23.04 | 22.05 | 24.10 |

| 60 | 18.45 | 17.64 | 19.36 | 17.87 | 17.08 | 18.77 | 21.02 | 20.11 | 21.98 | 19.54 | 18.93 | 20.20 |

| 65 | 14.99 | 14.37 | 15.70 | 14.66 | 14.16 | 15.22 | 17.68 | 17.20 | 18.18 | 15.99 | 15.35 | 16.69 |

| 70 | 12.10 | 11.60 | 12.66 | 12.09 | 11.79 | 12.43 | 14.08 | 13.81 | 14.39 | 12.89 | 12.48 | 13.33 |

| 75 | 9.37 | 8.97 | 9.80 | 9.36 | 9.49 | 9.23 | 11.44 | 11.40 | 11.49 | 9.74 | 9.19 | 10.33 |

| 80 | 7.97 | 7.61 | 8.34 | 8.01 | 7.97 | 8.07 | 9.16 | 9.41 | 8.92 | 8.24 | 7.77 | 8.71 |

| 85+ | 5.97 | 5.85 | 6.09 | 5.86 | 5.86 | 5.89 | 7.91 | 7.89 | 7.96 | 6.32 | 6.68 | 6.06 |

Table 4 presents the life expectancy at birth by region in India, which ranges from 64 to 69 years. With a difference of more than 5 years, the life expectancy was as low as 63.6 years (95% CI 63.12 - 64.05) in the East region compared with 68.7 years (95% CI 68.06 - 69.34) (see online supplementary appendix table 3) in the North region. However, the life expectancy at age 1 year was 68.7 years in the Northern region and 63.8 years in the northeast—a difference of 4.9 years. Similarly, among males, the life expectancy at birth ranged from 66.2 years (95% CI 65.42 - 67.09) in the west to 60.9 years (95% CI 59.16 - 62.58) (see online supplementary appendix table 3) in the northeast region—a difference of 5.3 years. At age 1 year, the gap in life expectancy by sex was as high as 8 years in the south followed by the northeast (5.5 years), north (5.4 years) and west (4.8 years). Below age 1 year, the gap in life expectancy by sex was lower in the eastern region. Similarly, life expectancy at birth for females was higher in the north region 71.8 years (95% CI 70.96 - 72.73) and lower in the eastern region 64.8 years (95% CI 64.15 - 65.45) (see online supplementary appendix table 3), a difference of 7.0 years.

Table 4.

Life expectancy across regions and sex in India, 2015–2016

| Age interval | Northeast | East | North | Central | West | South | ||||||||||||

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| Below 1 | 63.77 | 60.88 | 67.09 | 63.57 | 62.39 | 64.79 | 68.68 | 65.97 | 71.82 | 63.76 | 61.80 | 65.94 | 68.64 | 66.19 | 71.35 | 64.87 | 60.97 | 69.22 |

| 1 | 66.11 | 63.56 | 69.04 | 66.37 | 65.22 | 67.56 | 70.24 | 67.75 | 73.11 | 66.55 | 64.76 | 68.52 | 69.58 | 67.28 | 72.11 | 66.69 | 63.14 | 70.59 |

| 5 | 64.07 | 61.63 | 66.86 | 63.59 | 62.44 | 64.77 | 67.15 | 64.75 | 69.89 | 63.95 | 62.02 | 66.08 | 66.78 | 64.48 | 69.30 | 65.04 | 61.87 | 68.46 |

| 10 | 60.26 | 57.79 | 63.11 | 60.19 | 59.01 | 61.40 | 63.12 | 60.74 | 65.83 | 60.11 | 58.25 | 62.17 | 62.93 | 60.39 | 65.72 | 62.90 | 59.94 | 66.08 |

| 15 | 55.53 | 53.07 | 58.34 | 55.46 | 54.24 | 56.70 | 58.30 | 55.91 | 61.03 | 55.38 | 53.51 | 57.45 | 58.07 | 55.52 | 60.88 | 58.09 | 55.16 | 61.22 |

| 20 | 51.01 | 48.55 | 53.82 | 50.87 | 49.65 | 52.11 | 53.63 | 51.24 | 56.35 | 50.85 | 48.99 | 52.89 | 53.41 | 50.80 | 56.29 | 53.41 | 50.50 | 56.50 |

| 25 | 46.42 | 44.04 | 49.17 | 46.34 | 45.13 | 47.57 | 49.00 | 46.62 | 51.70 | 46.41 | 44.56 | 48.45 | 48.84 | 46.19 | 51.77 | 48.82 | 45.99 | 51.84 |

| 30 | 41.95 | 39.65 | 44.61 | 41.77 | 40.61 | 42.96 | 44.37 | 42.07 | 46.99 | 42.00 | 40.24 | 43.95 | 44.25 | 41.66 | 47.12 | 44.35 | 41.66 | 47.23 |

| 35 | 37.70 | 35.59 | 40.14 | 37.59 | 36.54 | 38.68 | 39.99 | 37.85 | 42.43 | 37.77 | 36.17 | 39.57 | 39.87 | 37.42 | 42.54 | 40.10 | 37.66 | 42.71 |

| 40 | 33.38 | 31.37 | 35.71 | 33.16 | 32.32 | 34.04 | 35.54 | 33.53 | 37.82 | 33.32 | 31.81 | 35.02 | 35.38 | 33.07 | 37.90 | 35.76 | 33.56 | 38.12 |

| 45 | 29.19 | 27.38 | 31.29 | 28.92 | 28.27 | 29.62 | 31.18 | 29.33 | 33.28 | 29.08 | 27.71 | 30.63 | 31.11 | 29.07 | 33.32 | 31.49 | 29.53 | 33.57 |

| 50 | 25.29 | 23.80 | 27.03 | 24.72 | 24.18 | 25.30 | 27.07 | 25.39 | 28.97 | 24.90 | 23.67 | 26.28 | 26.98 | 25.18 | 28.87 | 27.34 | 25.64 | 29.15 |

| 55 | 21.44 | 20.30 | 22.84 | 20.78 | 20.42 | 21.18 | 23.03 | 21.66 | 24.63 | 21.01 | 19.98 | 22.19 | 22.85 | 21.53 | 24.29 | 23.29 | 21.96 | 24.76 |

| 60 | 17.91 | 16.96 | 19.06 | 17.32 | 17.10 | 17.60 | 19.37 | 18.36 | 20.59 | 17.52 | 16.68 | 18.49 | 19.27 | 18.30 | 20.29 | 19.83 | 18.72 | 21.04 |

| 65 | 14.93 | 14.21 | 15.77 | 13.86 | 13.72 | 14.02 | 15.74 | 14.85 | 16.80 | 14.31 | 13.69 | 15.04 | 15.84 | 15.09 | 16.62 | 16.34 | 15.54 | 17.21 |

| 70 | 12.22 | 11.92 | 12.57 | 11.13 | 11.00 | 11.30 | 12.85 | 12.08 | 13.76 | 11.66 | 11.11 | 12.28 | 12.61 | 12.02 | 13.21 | 13.39 | 12.88 | 13.93 |

| 75 | 9.64 | 9.31 | 10.01 | 8.38 | 8.24 | 8.55 | 9.72 | 9.03 | 10.51 | 8.91 | 8.46 | 9.41 | 9.90 | 9.62 | 10.17 | 10.88 | 10.62 | 11.13 |

| 80 | 7.99 | 7.77 | 8.23 | 7.16 | 7.20 | 7.15 | 8.11 | 7.32 | 8.96 | 7.76 | 7.44 | 8.08 | 8.27 | 7.89 | 8.62 | 9.36 | 9.03 | 9.66 |

| 85+ | 6.01 | 5.74 | 6.29 | 4.94 | 5.18 | 4.74 | 6.28 | 5.63 | 6.95 | 5.67 | 5.67 | 5.68 | 6.49 | 6.70 | 6.38 | 7.55 | 7.35 | 7.72 |

The probability of death for adults (15–59 years) and premature mortality (before at age 70 years) were estimated by sex, caste, region and religion. Results were presented in tables 5 and 6. Table 5 shows that the level of adult mortality is higher among males than among females in India. Individuals belonging to STs have a higher probability of adult death (0.178) than SC groups (0.165). Similarly, by religion, the probability of death among Hindus was 0.147 compared with 0.145 among others, followed by 0.133 among Christians and 0.129 among Muslims. By region, the probability of adult death in the northeastern region was higher (0.167) than that in the central regions (0.158). Similarly, premature mortality by caste group revealed that individuals belonging to SCs had a higher probability of premature mortality than general castes (0.382 vs 0.301). Premature mortality was also analysed by religions and regions in India and was found to vary. For instance, Hindu (0.347) had a higher premature mortality than Muslim (0.341) and Christians (0.316). By region, the probability of premature mortality in the northeast was 0.385 followed by central 0.372, east 0.364, southern 0.349, western 0.303 and northern regions 0.294. Table 6 reveals that the adult mortality and premature mortality was higher among males than among females in each social strata; caste, religion and region in India. Premature mortality among males and females was high among STs (0.159) followed by SCs (0.127), OBCs (0.099) and others (0.097). Similarly, for religion, premature mortality gap was higher among Christians than among Hindu. Regional variations shows that the gap was wider in the south than in other regions.

Table 5.

Probability of death at age 15–60 years and premature mortality at age 70 years by caste, religion and region in India

| Probability of dying between n to x+n interval | ||||||

| Caste | SC | ST | OBC | Others | ||

| 45q15 | 0.1651 | 0.1783 | 0.1407 | 0.1223 | ||

| 70q0 | 0.3823 | 0.3811 | 0.3443 | 0.3006 | ||

| Religion | Hindus | Muslims | Christians | Others | ||

| 45q15 | 0.1466 | 0.1286 | 0.1326 | 0.1453 | ||

| 70q0 | 0.3473 | 0.3412 | 0.3164 | 0.3089 | ||

| Region | Northeast | East | North | Central | West | South |

| 45q15 | 0.1671 | 0.1520 | 0.1291 | 0.1575 | 0.1292 | 0.1380 |

| 70q0 | 0.3851 | 0.3636 | 0.2935 | 0.3724 | 0.3029 | 0.3493 |

OBC, other backward classes; SC, scheduled castes; ST, scheduled tribes.

Table 6.

Probability of death at age 15–60 years and premature mortality at age 70 years among different categories of caste, religion and region by sex in India

| Probability of dying between n to x+n interval | SC | ST | OBC | Others | ||||||||

| Caste | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||

| 45q15 | 0.2097 | 0.1201 | 0.2263 | 0.1307 | 0.1754 | 0.1064 | 0.1593 | 0.0861 | ||||

| 70q0 | 0.4430 | 0.3157 | 0.4567 | 0.2979 | 0.3923 | 0.2929 | 0.3478 | 0.2512 | ||||

| Religion | Hindus | Muslims | Christians | Others | ||||||||

| 45q15 | 0.1866 | 0.1067 | 0.1523 | 0.1059 | 0.1815 | 0.0869 | 0.1842 | 0.1065 | ||||

| 70q0 | 0.4018 | 0.2886 | 0.3828 | 0.2967 | 0.3888 | 0.2394 | 0.3606 | 0.2542 | ||||

| Probability of dying between n to x+n Interval | Northeast | East | North | Central | West | South | ||||||

| Regions | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| 45q15 | 0.2142 | 0.1197 | 0.1795 | 0.1253 | 0.1655 | 0.0925 | 0.1879 | 0.1271 | 0.1753 | 0.0830 | 0.1884 | 0.0891 |

| 70q0 | 0.4464 | 0.3144 | 0.3945 | 0.3318 | 0.3500 | 0.2321 | 0.4179 | 0.3233 | 0.3655 | 0.2353 | 0.4234 | 0.2683 |

Prior studies suggests that caste and religion differentials show inequality in mortality across populations, subgroups and geographic areas.44 60 61 This study addresses social disparities in health and provides evidence for the gap in life expectancy and premature mortality across different social groups in India.

Discussion

Life expectancy at birth is widely used as a summary measure of health. Disaggregated estimates of life expectancy are limited in many developing countries including India. This is the first ever study that estimates life expectancy at birth and premature mortality by social groups such as caste, religion and region in India. The following are salient findings of this study.

First, life expectancy at birth varies largely across caste, religion and region in India. Life expectancy at birth among SCs was lowest, followed by STs, OBCs and Others. Second, the caste and religion differentials in life expectancy were observed at birth and across the ages. Life expectancy at birth was highest among Christians followed by others, Muslims and Hindus. The gap in life expectancy at birth between Christians and Hindus was 3 years. It was low in the central region compared with the western region at age below 1 year. Third, we found consistent sex differentials in life expectancy across caste and religious groups. Life expectancy at birth for women was higher for men across social groups in both rural and urban areas. Fourth, adult mortality (45q15) was highest among SCs. However, in the case of religion, the probability of adult death (45q15) was higher among Hindus than among Muslims. The probability of death was higher among Northeast than in the Western region in India. Fifth, premature mortality (70q0) was highest among SCs. In the case of religion, premature deaths (0q70) among Muslims was higher than among Christians. By region, premature mortality (70q0) in the Northeast was higher than in the North.

We put forward the following explanations. Life expectancy has been explained by a combination of biological and behavioural factors.47 The caste system, with its societal stratification and social restrictions, continues to have a major impact in India.62 Caste and religion are inextricably linked to and is a proxy for SES in India. The poor SES is significantly associated with poor health outcomes and lower access to healthcare facilities. The benefits of caste-based employment, education and health schemes are largely availed by better off within the deprived caste group. As a result, the average remained low and poor are getting poorer. Similarly, gender variations in health are persistent cutting across caste and religion. Though women are living longer than men, they have higher morbidity and disability at later ages.63 The average year of disability free life expectancy among females was lower than among male. Adult mortality risks could be a result of chronic diseases or malnutrition in childhood. Most of the non-communicable diseases are non-curable but can be controlled with regular treatment. However, while the risk of being affected by these lifestyle conditions is relatively lower among the poor, once affected, they cannot afford the continued high treatment costs and so they experience premature death. The findings indicate significant differences in the population’s health across different castes, religions and regions. Hindu children have higher mortality than Muslim children.64

The study has some limitations too. Several studies indicates that SES and educational attainment significantly associated with adult deaths. The scope of further research is to examine the differential within caste group, say poor and rich within SCs and STs, which is not captured in the study. We believe that the inequality within the caste group is high and contribute to mortality differentials and longevity. Second, the life expectancy in the paper is not comparable with the SRS due to non-use of adjustment factor used in estimation of CI. The CI and life expectancy was estimated without adjustment factor. Third, the paper provide result of probability of dying and life expectancy without adjusting for cause of death across the caste, religion and region.

The reduction of premature mortality, a major public health focus, is one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.65 The mortality rate has decreased for most age groups from 2000 to 2016, especially for adolescents and young adults in many developed and developing regions, but remains high among middle-aged adults (ages 36–55 years) and older adults (55 years). However, premature mortality and adult mortality are still higher among all ethnic groups globally.66–68

Conclusion

The findings suggest that the mortality differentials are significant across caste, religion and region in India. Though, female life expectancy at birth is higher for females, they might be suffering from higher morbidity. Premature mortality is high across caste and religious groups. Prioritising reduction of premature mortality, including infant and under-five mortality, is recommended.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank editor and reviewers for their useful suggestions in revising the earlier draft. Authors would also like to thank Mr Suyash Mishra for his useful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design of the study: both authors. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: both authors; drafting the manuscript: both authors; revising the manuscript critically for important content: SKM.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository: https://dhsprogram.com/what-we-do/survey/survey-display-355.cfm and https://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/Appendix_SRS_Based_Life_Table.html.

References

- 1.WHO World health statistics 2016 monitoring health for the SDGs. Geneva, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerry CJ, Raskina Y, Tsyplakova D. Convergence or divergence? life expectancy patterns in post-communist countries, 1959-2010. Soc Indic Res 2018;140:309–32. 10.1007/s11205-017-1764-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joe W, Liou L, Subramanian SV. Increasing global heterogeneity in the life expectancy of older populations. bioRxiv 2019;589630. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson C. Understanding global demographic convergence since 1950. Popul Dev Rev 2011;37:375–88. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMichael AJ, McKee M, Shkolnikov V, et al. Mortality trends and setbacks: global convergence or divergence? Lancet 2004;363:1155–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15902-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moser K, Shkolnikov VM, Leon DA, et al. Divergence replaces convergence from the late 1980s BT - HIV, resurgent infections and population change in Africa. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2007: 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459–544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations. Department of International Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division Sex differentials in survivorship in the developing world: levels, regional patterns and demographic determinants. Popul Bull UN 1988;51:51–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glei DA, Horiuchi S. The narrowing sex differential in life expectancy in high-income populations: effects of differences in the age pattern of mortality. Popul Stud 2007;61:141–59. 10.1080/00324720701331433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanfongnon R, Bourbeau R. Sex differential in life expectancy at birth in Canada 1921-2004: provincial variations, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubey M, Ram U, Ram F. Threshold levels of infant and under-five mortality for crossover between life expectancies at ages zero, one and five in India: a decomposition analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0143764. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh A, Ladusingh L. Life expectancy at birth and life disparity: an assessment of sex differentials in mortality in India. Int J Popul Stud 2016;2 10.18063/IJPS.2016.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GBD 2017 Mortality Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2018;392:1684–735. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31891-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassett MT, Krieger N. Social class and black-white differences in breast cancer survival. Am J Public Health 1986;76:1400–3. 10.2105/AJPH.76.12.1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keil JE, Sutherland SE, Knapp RG, et al. Does equal socioeconomic status in black and white men mean equal risk of mortality? Am J Public Health 1992;82:1133–6. 10.2105/AJPH.82.8.1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hummer RA, Rogers RG, Eberstein IW. Sociodemographic differentials in adult mortality: a review of analytic approaches. Popul Dev Rev 1998;24:553–78. 10.2307/2808154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagstaff A. Socioeconomic inequalities in child mortality: comparisons across nine developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78:19–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowd K, Blake D, Cairns AJG. Facing up to uncertain life expectancy: the longevity fan charts. Demography 2010;47:67–78. 10.1353/dem.0.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh A, Pathak PK, Chauhan RK, et al. Infant and child mortality in India in the last two decades: a geospatial analysis. PLoS One 2011;6:e26856. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eggleston KN, Fuchs VR. The new demographic transition: most gains in life expectancy now realized late in life. J Econ Perspect 2012;26:137–56. 10.1257/jep.26.3.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenelon A. Geographic divergence in mortality in the United States. Popul Dev Rev 2013;39:611–34. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00630.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon E-S, Haklai Z, Meron J, et al. Regional variations in mortality and causes of death in Israel, 2009-2013. Isr J Health Policy Res 2017;6:39. 10.1186/s13584-017-0164-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Chu Y, Oza S, et al. National, regional, and state-level all-cause and cause-specific under-5 mortality in India in 2000-15: a systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e721–34. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30080-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery AL, Ram U, Kumar R, et al. Maternal mortality in India: causes and healthcare service use based on a nationally representative survey. PLoS One 2014;9:e83331. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knudson A, Meit M, Tanenbaum E, et al. Exploring rural and urban mortality differences. Bethseda Rural Heal Reform Policy Res Cent 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saikia N. Trends in mortality differentials in India, 2016: 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakraborti B. Rural-urban mortality differential in Indian states: effect of environmental inequality and associated factors. Rural Demogr 1982;9:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartley D. Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1675–8. 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969-2009. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:e19–29. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah VR, Christian DS, Prajapati AC, et al. Quality of life among elderly population residing in urban field practice area of a tertiary care Institute of Ahmedabad city, Gujarat. J Family Med Prim Care 2017;6:101–5. 10.4103/2249-4863.214965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnaji N, James KS. Gender differentials in adult mortality: with notes on rural-urban contrasts. Econ Polit Wkly 2002:4633–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saikia N, Jasilionis D, Ram F. Trends in geographical mortality differentials in India. Rostock Max Planck Inst Demogr Res 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ram U, Jha P, Gerland P, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific adult mortality risk in India in 2014: analysis of 0·27 million nationally surveyed deaths and demographic estimates from 597 districts. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e767–75. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00091-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kannan KP, Thankappan KR, Ramankutty V, et al. Kerala: a unique model of development. Health Millions 1991;17:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pal P, Ghosh J. Inequality in India: a survey of recent trends, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen A. Development as freedom (1999). N Glob Dev Read Perspect Dev Glob Chang 2014;2:525–47. [Google Scholar]

- 37.GBD 2016 Mortality Collaborators Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1084–150. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31833-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohindra KS, Haddad S, Narayana D. Women's health in a rural community in Kerala, India: do caste and socioeconomic position matter? J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:1020–6. 10.1136/jech.2006.047647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Subramanian SV. Health inequalities in India: the axes of stratification. Brown J World Aff 2008;14. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vart P, Jaglan A, Shafique K. Caste-based social inequalities and childhood anemia in India: results from the National family health survey (NFHS) 2005-2006. BMC Public Health 2015;15:537. 10.1186/s12889-015-1881-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:757–71. 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00073-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kakwani N, Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: measurement, computation, and statistical inference. J Econom 1997;77:87–103. 10.1016/S0304-4076(96)01807-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burström K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F. Increasing socio-economic inequalities in life expectancy and QALYs in Sweden 1980-1997. Health Econ 2005;14:831–50. 10.1002/hec.977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subramanian SV, Davey Smith G, Subramanyam M. Indigenous health and socioeconomic status in India. PLoS Med 2006;3:e421. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorant V, Croux C, Weich S, et al. Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:293–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malhotra C, Do YK. Socio-economic disparities in health system responsiveness in India. Health Policy Plan 2013;28:197–205. 10.1093/heapol/czs051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asaria M, Mazumdar S, Chowdhury S, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in life expectancy in India. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001445. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohanty SK, Ram F. Life expectancy at birth among social and economic groups in India. IIPS India, 2010. http://iipsindia.org/pdf/RB-13fileforuploading.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coffey D, Deshpande A, Hammer J, et al. Local social inequality, economic inequality, and disparities in child height in India. Demography 2019;56:1427–52. 10.1007/s13524-019-00794-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LoPalo M, Coffey D, Spears D. The consequences of social inequality for the health and development of India’s children: the case of caste, sanitation, and child height. Soc Justice Res 2019;32:239–54. 10.1007/s11211-019-00323-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel P, Das M, Das U. The perceptions, health-seeking behaviours and access of scheduled caste women to maternal health services in Bihar, India. Reprod Health Matters 2018;26:114–25. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1533361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Acharya SS. Health equity in India: an examination through the lens of social exclusion. J Soc Incl Stud 2018;4:104–30. 10.1177/2394481118774489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khubchandani J, Soni A, Fahey N, et al. Caste matters: perceived discrimination among women in rural India. Arch Womens Ment Health 2018;21:163–70. 10.1007/s00737-017-0790-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caste GS. Caste and care: is Indian healthcare delivery system favourable for Dalits? Institute for Social and Economic Change, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malhotra R, Rajan I, Syam S, et al. Social group disparities in life expectancy and active life expectancy among older persons in Kerala, India. Innov Aging 2018;2:230 10.1093/geroni/igy023.855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guillot M, Gavrilova N, Torgasheva L, et al. Divergent paths for adult mortality in Russia and central Asia: evidence from Kyrgyzstan. PLoS One 2013;8:e75314. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andreev EM, Shkolnikov VM. Spreadsheet for calculation of confidence limits for any life table or healthy-life table quantity. Rostock: Max Planck Inst Demographic Research (MPIDR) Technical Report-5, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Preston Samuel H, Patrick H, Michel G. Demography: measuring and modeling population processes. MA Blackwell Publ, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chiang CL. On constructing current life tables. J Am Stat Assoc 1972;67:538–41. 10.1080/01621459.1972.10481245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schoen R. Calculating life tables by estimating Chiang's a from observed rates. Demography 1978;15:625–35. 10.2307/2061212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Irving M, et al. The mortality divide in India: the differential contributions of gender, caste, and standard of living across the life course. Am J Public Health 2006;96:818–25. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borooah VK, Dubey A, Iyer S. The effectiveness of jobs reservation: caste, religion and economic status in India. Dev Change 2007;38:423–45. 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00418.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vijayanath V, Anitha MR, Vijayamahantesh SN, et al. Caste and health in Indian scenario. J Punjab Acad Forensic Med Toxicol 2010;10:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saikia N, Bora JK. Does increasing longevity lead increasing disability? Evidence from Indian states. Soc Chang Dev 2016;13. [Google Scholar]

- 65.IIPS, ORC Macro . National family health survey (NFHS-3) 2005-2006. Mumbai, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Norheim OF, Jha P, Admasu K, et al. Avoiding 40% of the premature deaths in each country, 2010-30: review of national mortality trends to help quantify the UN sustainable development goal for health. Lancet 2015;385:239–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61591-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu L, Hill K, Oza S. Levels and causes of mortality under age five years In: Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: disease control priorities, 2015: 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Masquelier B, Hug L, Sharrow D, et al. Global, regional, and national mortality trends in older children and young adolescents (5-14 years) from 1990 to 2016: an analysis of empirical data. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1087–99. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30353-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035392supp001.pdf (125.1KB, pdf)