Abstract

Objective

Patients’ expectations—as a central mechanism of placebo and nocebo effects—are an important predictor of health outcomes. However, the lack of a way to assess expectations across different settings restricts progress in understanding the role of expectations and to quantify their importance in medical and psychological treatments. The aim of this study was to develop a theory-based, generic, multidimensional measure assessing patient expectations of medical and psychological treatments.

Design

The Treatment Expectation Questionnaire (TEX-Q) was developed based on the integrative model of expectations and a systematic literature review of treatment expectation scales. After creating a comprehensive item pool, the scale was further refined by use of expert ratings and patient interviews.

Setting

Patients were recruited in primary care at two hospitals in Hamburg, Germany.

Participants

13 scientific experts participated in the expert survey. 11 patients waiting for psychological or surgical treatments participated in the qualitative interviews.

Results

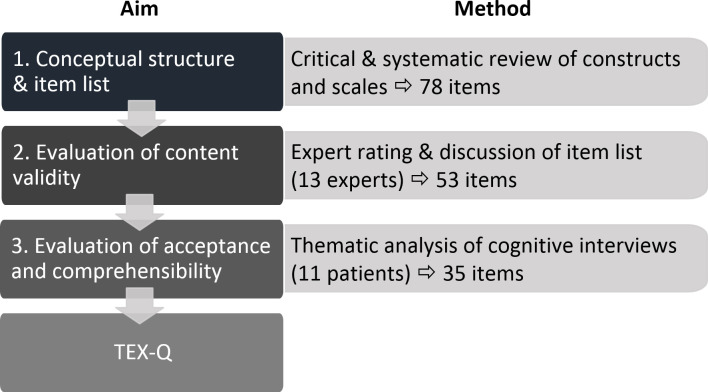

The 2×2×2 multidimensional structure of the TEX-Q assesses two expectation constructs (probabilistic vs value-based) across two outcome domains with two valences (direct benefits and adverse events, broader positive and negative impact), plus process and behavioural control expectations. We examined 583 items from 38 scales identified in the systematic review and developed 78 initial items. Content validity was then rated by experts according to item fit and comprehensibility. The best 53 items were further evaluated for comprehensibility, acceptability, phrasing preference and understanding by interviewing patients prior to treatment using the ‘think aloud’ technique. This resulted in a first 35-item version of the TEX-Q.

Conclusions

The TEX-Q is a generic, multidimensional measure to assess patient expectations of medical and psychological treatments and allows comparison of the impact of multidimensional expectations across different conditions. The final TEX-Q will be available after psychometric validation.

Keywords: general medicine (see internal medicine), mental health, preventive medicine, qualitative research, statistics & research methods, therapeutics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A generic, multidimensional scale measuring patients’ treatment expectations is constructed.

The conceptual model contains eight subscales for outcome expectations and two process expectations.

The study employed a three-step empirical process: systematic review, expert ratings and cognitive patient interviews.

Generation and iterative reformulation of items were informed by empirical steps.

The generic nature of the Treatment Expectation Questionnaire needs further research in additional clinical settings.

Introduction

Patients’ treatment expectations are an important predictor of outcome for a broad range of medical and psychological treatments.1–3 As non-specific treatment components, they can induce subjective and psychological changes and are a central mechanism driving placebo and nocebo effects.4 Positive treatment expectations have been linked to health outcomes for a variety of different illnesses and treatments, including cancer,5 stroke,6 musculoskeletal disorders,7 8 pain,9 surgery,10 11 antidepressant medication12 and psychotherapy.3 Furthermore, negative expectations have been linked to the occurrence of adverse events in the treatment of a number of illnesses.5 13 14 Generally, studies find a moderate overall effect of patients’ expectations on outcomes.15 16

The large number of treatment expectation measures has been identified as an important limitation for the integration of the existing evidence across different treatments and diseases in several systematic reviews.1 15–17 On the level of assessment, this stems from most studies developing a single treatment or disease measure of expectations18 often using single-item or very brief non-validated ad-hoc instruments.10 15 Other questionnaires only assess partial aspects of expectations, for example only positive expectations,19 or do not distinguish between the types of expectations assessed.20

On the conceptual level, there is a diversity of underlying theories on expectations, being one of the most studied constructs in psychology.21 The theoretical conception of the Treatment Expectation Questionnaire (TEX-Q) is based on our integrative model of expectations in patients undergoing medical treatment,18 and on an extensive review of the expectation literature. The model defines treatment expectations as future-directed cognitions that focus on the incidence or non-incidence of a specific event or experience. In general, it distinguishes between probabilistic expectations, describing realistic estimations about the future, and ideal or value-based expectation, describing what someone would like or dislike to happen (eg, hopes, fears). It defines treatment expectations in distinction from behavioural expectations about the subjective control over the treatment, as well as generalised expectations (eg, generalised self-efficacy, optimism) and expectations about the timeline of diseases, treatments, behaviour or related outcomes. Regarding treatment expectations, the model distinguishes between outcome-related expectations about the benefits and side effects of the treatment and structural and process-related expectations about the course of the treatment itself. Furthermore, it differentiates outcomes continuously, ranging from internal effects (eg, symptom improvement) to external effects (eg, impact on patients’ social life). The integrative model itself aims to integrate several central expectation theories. For further conceptual clarity, two of those theories with high relevance for the development of the TEX-Q are discussed in more detail.

The most central understanding of treatment expectations was provided by Kirsch’s response expectancy theory.22 Here he distinguishes between two kinds of general outcome expectations: stimulus expectancies, which are a person’s expectation of external stimuli as an outcome, and response expectancies, which refer to a person’s expectations of a non-volitional internal response as an outcome. Response expectancies are particularly relevant in treatment contexts. They provide a description of patients’ expectations in a broad range of treatment situations, ranging from their position of passive recipients in some instances (eg, expecting that taking metformin will lower your blood sugar in diabetes) to more active patient roles involving volitional health-directed behaviour (eg, expecting that changing your lifestyle will lower your blood sugar).

Another important theory influencing the development of the TEX-Q is Leventhal et al’s common-sense model of illness representation.23 This model describes patients’ subjective representations of their illness and its consequences for their lives. It differentiates beliefs about the causes of the illness, its timeline, the identity of the illness through its associated symptoms, and the possibility to control the illness through personal behaviour and the treatment itself. The model does not refer to expectations explicitly, but they are regarded as important general constructs underlying illness beliefs.24 Thus, the model presents an elaborate differentiation of patients’ illness and treatment beliefs that can also be applied as a framework for the differentiation of treatment expectations.

To facilitate a comprehensive understanding of treatment expectations and overcome the limitations of previous scales, we developed the TEX-Q. It was constructed with the following five aims: (1) the scale will be able to measure treatment expectations generically and comparably for different medical and psychological treatments; (2) the scale will be multidimensional, taking into account aspects of treatment expectations with potential predictive links to treatment outcomes; (3) the scale will be sensitive to change in order to capture effects of expectation management interventions; and (4) the scale’s conceptual framework is applicable to research and everyday clinical practice.

Methods

Overview of the development process

The development process of the TEX-Q followed three main steps (see figure 1). First, we developed a conceptual structure for the TEX-Q and created a comprehensive item pool. This step was based on the integrative model of expectations18 and a systematic literature review of treatment expectation scales. Second, expert ratings were obtained to evaluate the items’ content validity. Third, we conducted qualitative cognitive interviews with patients to evaluate the comprehensibility and acceptance of the items and the fit among our target population. Informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study. The TEX-Q was developed in German. Preliminary English translations of its contents are used in this paper. A final translation will be available after the finalisation of its psychometric validation.

Figure 1.

Overview of the development process of the Treatment Expectation Questionnaire (TEX-Q).

Conceptual structure and generation of item list

The conceptual structure of the TEX-Q was developed based on the most relevant expectation theories22 23 incorporated in our integrative model of expectations.18 Our goal for the conceptual structure was to cover a relevant range of treatment-related expectation constructs with potential predictive value for outcome. At the same time, we aimed to include concepts that can be generically assessed.

First, a comprehensive list of existing scales relevant to the development process was assembled through a literature review of generic and treatment-specific scales. To do this we completed a systematic literature search of PubMed and PsycINFO databases (last date of search: 1 August 2018). The search was designed to include all published articles describing empirical studies with adults that featured a scale to measure patient expectations written since 1900 in English language (for the specific search term, see online supplementary appendix A). The articles found were then screened in two steps: first regarding titles and abstracts and second regarding the full texts of the remaining articles. A review protocol can be obtained from the authors.

bmjopen-2019-036169supp001.pdf (680.9KB, pdf)

Second, the systematic review was complemented by a critical review of treatment-specific expectation scales. As a systematic review of treatment-specific scales would have by far exceeded reasonable capacities for our purpose, our approach was non-systematic. This review was based on our integrative model of expectations,18 treatment-specific reviews of expectation scales6 10 15 17 25 26 and treatment-specific scales identified in our search for generic scales. For all identified expectation scales, the references of the respective publications were screened and additional scales were included.

The identified scales were assessed in conjunction with our theoretical model to finalise the conceptual structure and subscales of the TEX-Q. The items from each identified scale provided the pool from which we selected our items. Through the exclusion of duplicates and items that did not fit with the model, we created the first list of potential items for the TEX-Q.

Evaluation of content validity

Our next empirical aim was the evaluation of content validity. To do this we sent our item list to 13 experts from the fields of placebo research, psychosomatic medicine and clinical psychology. They were requested to rate each item on a 6-point Likert scale according to (1) comprehensibility, (2) fit to our theoretical construct (which we introduced attached to the rating) and (3) overall quality of the item. Furthermore, they were asked to provide open feedback for each item. After ranking the items for each dimension and taking into account the commentaries given, we decided on the inclusion and eventual rewording of the most appropriate items.

Evaluation of comprehensibility and acceptance

Next, we evaluated the comprehensibility of the items, their acceptability and fit to our model in a clinical sample. We therefore conducted cognitive interviews with patients. We recruited a convenience sample of 11 patients waiting for psychological or surgical treatments at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf and the Schön Hospital Hamburg-Eilbek. In the selection of these patients for the interviews, we aimed to maximise the diversity of conditions and treatments. Patients were interviewed by male and female researchers with prior experience with this assessment (JA and MAG). Data saturation was discussed regularly and data collection was continued until we found it to be sufficient within this sample.

Based on a semistructured interview guide (see online supplementary appendix B), the patients were asked to complete the potential TEX-Q items, some of them in different phrasings to examine the differences, while speaking out their thoughts (think aloud technique27). Furthermore, they were asked open questions about prior experiences and expectations with their symptoms and treatment and about specific aspects of the phrasing of the items. The interviews took about 1 hour each. The interviews were audio-recorded and the answers to the open questions were transcribed verbatim. Additionally, the researcher took field notes of any observed difficulty the patients had in filling out the questionnaire.

The transcripts and notes from the interviews were qualitatively analysed using thematic analysis.28 Two different analyses were conducted. First, we looked at how patients expressed their expectations throughout the interviews, examining their fit to our conceptual model. Second, we examined the materials for all criticisms about the questionnaire and its items. Categories for both analyses were created both deductively based on our conceptions and inductively derived from the interviews. The analyses of the interviews then informed the final discussion and selection process from which the research team chose the wording of the items for the TEX-Q.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the TEX-Q was evaluated through patient involvement in the third empirical step, as presented above in detail. Through the qualitative interviews, the phrasing of our items was adjusted according to their priorities, experience and preferences. The results of their involvement will be disseminated to the patients through the publication of the final TEX-Q questionnaire. There was no further patient or public involvement in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study.

Results

Literature review: conceptual model of the TEX-Q

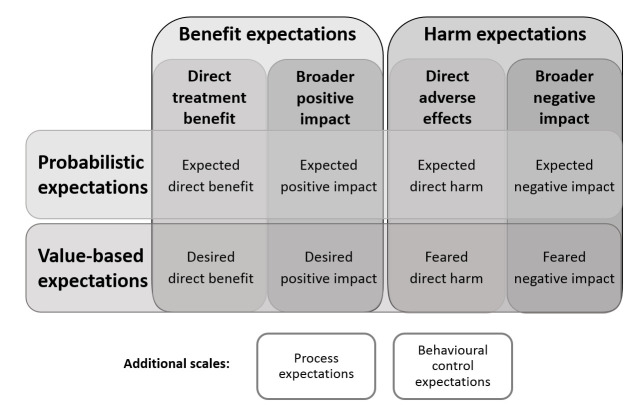

The literature review generally provided additional support for the integrative model of expectations,18 with all reviewed items fitting to one or more of the aspects of expectations differentiated in the model. Some of the scales reviewed, however, focused more specifically on one or more aspects of the model and therefore introduced additional, more nuanced differentiations within it. Our rationale was to capture the most potentially relevant aspects of this expectations with predictive value for outcome in the TEX-Q. Hence, we developed a 2×2×2 concept to operationalise outcome expectations in the questionnaire (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual structure of the Treatment Expectation Questionnaire (TEX-Q). Cells describe the theorised subscales of TEX-Q.

First, we distinguished probabilistic expectations, describing realistic assumptions about what is likely to happen (eg, expecting symptom improvement) from value-based expectations, describing more affective, less rational feelings like hopes or fears (eg, hoping to be pain-free). Our rationale here was to capture the potentially different predictive value of these expectation constructs as theorised in the literature.16 18 Second, we distinguished expectations about beneficial outcomes (eg, treatment success) from expectations about harmful outcomes (eg, complications). This inclusion was based on empirical evidence from the literature pointing to these aspects being separate dimensions rather than two sides of a unidimensional structure.29 Third, we distinguished expectations about direct, symptom-related treatment outcomes (eg, benefit or side effects) from expectations about the broader impacts of the treatment (eg, improved quality of life or reduced functioning). We thereby introduced a categorial operationalisation of the range of possible treatment outcomes described in the integrative model of expectations as relevant for different treatment outcomes to secure generic applicability.18 22 The eight terms depicted in the central cells of figure 2 describe the resulting theorised subscales of the TEX-Q. In addition to the aforementioned scales measuring outcome expectations, we included two additional subscales. The first was process-related expectations (eg, a straightforward procedure), based on the assumption that the expectations and experiences of the treatment process will be related to treatment outcome particularly in long-lasting treatments.18 23 24 The second was the expected behavioural control of the treatment (eg, being able to influence treatment success), based on the rationale these capture situation-specific correlates of generalised self-efficacy.30 In total this led to 10 different theorised subscales for the TEX-Q.

We refrained from the inclusion of further nuanced views from the conceptualisation of the TEX-Q for the sake of its applicability and generic nature. We also excluded general expectation constructs from our conceptualisation, as the TEX-Q was planned to focus on expectations about medical and psychological treatments, and good measures for relevant general expectation constructs like self-efficacy or optimism already exist.31 32 Furthermore, we had to exclude the timeline dimension of treatment expectations due to the dissimilarity of timelines in different treatments and the resulting lack of potential generic formulations possible in its operationalisation.

Literature review: generation of item list

For generic treatment expectation scales, our systematic search strategy identified 9312 articles. The additional critical review of treatment-specific expectation scales led to the inclusion of further 33 relevant articles, resulting in a total of 9345 articles. After the removal of duplicates, 7888 records remained. The screening of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 7849 articles which did not mention instruments measuring expectations. After assessment of the remaining 40 articles in full text, one article was excluded for not presenting an expectation measurement. A detailed overview of the review process is depicted in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart in online supplementary appendix C figure 1. The search strategies resulted in 39 articles containing 38 different relevant scales in total, of which 13 were multidimensional and 25 were unidimensional, the latter relating to 16 different treatments. Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of all scales found. The scales contained a total of 583 relevant items that provided inspiration for our primary item pool.

Table 1.

Comprehensive list of scales measuring patients’ treatment expectations

| Instrument | Treatment specificity | Dimensionality | Number of relevant items |

| Illness Perception Questionnaire, Brief and Revised (IPQ-R/B-IPQ)42 43 | Generic | Multi | 32 |

| Milwaukee Psychotherapy Expectancies Questionnaire (M-PEQ)34 | Generic | Multi | 13 |

| Patient Centered Outcomes Questionnaire (PCOQ)36 | Generic | Multi | 5 |

| Patient Questionnaire on Therapy Expectation and Evaluation (PATHEV)35 | Generic | Multi | 7 |

| Questionnaire for Patients’ Expectations of Healthcare (QPEHC)16 | Generic | Multi | 36 |

| Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ)38 | Generic | Single | 6 |

| Expectations for Activities of Daily Living (ADL-E)44 | Generic | Single | 22 |

| Expected Illness-Related Disability (PDI-E)45 | Generic | Single | 7 |

| General Assessment of Expected Side Effects Scale (GASE-EXPECT)46 | Generic | Single | 36 |

| General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)31 | Generic | Single | 10 |

| Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R)32 | Generic | Single | 6 |

| Physical Functioning Quality of Life Component Score (PCS-E)47 | Generic | Single | 13 |

| Positive Health Expectations Scale (PHES)20 | Generic | Single | 7 |

| Stanford Expectations of Treatment Scale (SETS)29 | Generic | Single | 9 |

| Treatments Representations Inventory (TRI)48 | Generic | Single | 28 |

| Expectations About Counseling-Brief Form (EACB)49 | Specific | Multi | 66 |

| Expectations of Gynecological Treatment Questionnaire (EGTQ)50 | Specific | Multi | 24 |

| Exercise Outcomes Expectations Questionnaire (EOE-Q)51 | Specific | Multi | 20 |

| Expectations Towards Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapy (EXPECT-ICD)52 | Specific | Multi | 10 |

| Orthodontic Treatment Expectations53 | Specific | Multi | 15 |

| Self-Efficacy Expectations and Outcome Expectations after Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Implantation (SE-ICD and OE-IC)54 | Specific | Multi | 17 |

| Smoking Abstinence Expectancies Questionnaire (SAEQ)55 | Specific | Multi | 28 |

| Psychosocial Treatment Expectations Questionnaire (PTEQ)56 | Specific | Multi | 13 |

| Acupuncture Expectancy Scale (AES)57 | Specific | Single | 7 |

| Anaesthesiological Expectations Questionnaire (ANP-E) 58 | Specific | Single | 17 |

| Cardiac Surgery Patient Expectations Questionnaire (C-SPEQ)59 | Specific | Single | 20 |

| Chiropractic Patients’ Expectations60 | Specific | Single | 15 |

| Control Attitudes Scale-Revised (CAS-R)61 | Specific | Single | 3 |

| Expectations for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments Questionnaire (EXPECT)62 | Specific | Single | 13 |

| Expectations Questionnaire (EQ)63 | Specific | Single | 6 |

| Future Expectations Regarding Life with Heart Disease Scale (FERLHDS)64 | Specific | Single | 18 |

| Hospital for Special Surgery Knee Surgery Expectations Survey (KSES)19 | Specific | Single | 23 |

| Knee Self-Efficacy Scale (K-SES)65 | Specific | Single | 22 |

| Musculoskeletal Outcomes Data Evaluation and Management System (MODEMS)66 | Specific | Single | 6 |

| New Knee Society Knee Scoring System (NKSSS)67 | Specific | Single | 8 |

| Patient Shoulder Outcome Expectancies (PSOE)68 | Specific | Single | 3 |

| Sample Patient Questionnaire (SPQ)69 | Specific | Single | 12 |

| Treatment-Specific Optimism (TSO)70 | Specific | Single | 10 |

The format of the table has been adapted from Laferton et al.18

Generic: not directly referring to a specific treatment.

Multi: several expectation dimensions are each assessed by an independent scale.

Single: only one expectation dimension is assessed.

Specific: directly referring to a specific treatment.

Based on this list, all authors took part in an iterative discussion process about the construction of the scale and its potential items. In that process, the items were further evaluated regarding their fit to our conceptual model, their applicability as generic items and our overall impression of them. Several items were reformulated to make them more generic and additional ones were constructed. With the deletion of duplicates and those substantially overlapping content-wise, as well as those we consensually found to not fit our conceptual model, we selected 78 items, each clearly associated with one of our conceptual subscales. These provided the basis for the further development of the TEX-Q.

Expert ratings: evaluation of content validity

The ratings showed a high level of approval for our items, with each global rating ranging between 4.0 and 5.9 (M=4.35, SD=0.30) on a 6-point Likert scale. All items were rated as comprehensible (range: 4.5–5.9, M=4.55, SD=0.31) and fitting our theoretical framework (range: 4.9–6.0, M=4.32, SD=0.21).

The commentary section of the ratings contained criticism about the wording of approximately one-third of the items. Eight different items were supposed to double-load on more than one of the theoretical subdimensions. In 15 items the use of technical terms, for example, functionality (German: Funktionsfähigkeit) and adverse effects (negative Effekte), was criticised for being potentially difficult to understand for patients. The synonymous use of different verbs for expectations and hopes, for example, to hope (hoffen) and to wish for (sich wünschen) was identified as a problem.

The rating results guided the further discussion process in the research team that resulted in the rewording of several items and a ranking of the items for each subscale according to the received rating and its variance. It was followed with a reduction to 53 items with 5–6 items per subscale by consensual decision in the research team.

Cognitive interviews: evaluation of comprehensibility and acceptance

The qualitative analysis of patients’ treatment expectations identified eight major expectation themes. Of these, six themes fitted our theoretical model, with 60 statements that could clearly be assigned to one of the hypothesised subdimensions of the TEX-Q. The two other themes were the absence of expectations (eg, “I do not expect anything in particular,” ID: 1001) with 11 mentions, and an unspecific feeling of stress about the treatment mentioned two times (eg, “I am tense how this will proceed,” ID: 1003). The results of this analysis were interpreted as support for our conception of the TEX-Q. Therefore, this conception was retained for the construction of the scale.

The analysis of criticism about the items, derived from the interview transcripts as well as the interviewers’ notes, led to identification of four major aspects of criticism. Each of these aspects had implications for the presentation and phrasing of the TEX-Q that directly informed our construction of the scale’s initial version (table 2). Especially aspect 4 was broadly discussed with the aim to capture both the probabilistic and strength-related aspects of expectations in an easily comprehensible way, resulting in the reformulation of all remaining items into a change question format and the addition of a brief introductory text asking patients to assess their expectations ‘as realistically as possible’. Furthermore, various item-level criticisms on the content and wording of specific items were identified as minor themes of criticism and led to a modification or deletion of the respective items.

Table 2.

Aspects of qualitative analysis and consequences for questionnaire development

| Aspects of criticism | Illustrative examples | Implications for development process |

| Aspect 1: commentary on the preferred wording of the anchors of the Likert scales. | “The anchors don’t match the question, seems like they are asking for two different things in one question.” (ID: 1002) Commentary about item 2b: How much improvement in your condition do you expect? Anchors: 0 (no change)/10 (largest possible improvement). |

|

| ||

| Aspect 2: comparison of analogue phrasings for key constructs to hope/to expect/to fear with phrasings like to think or to wish. | “To wish for something isn’t reality, you can wish for inaccessible things, to hope for something is more realistic.” (ID: 1004) |

|

| ||

| Aspect 3: evaluation of the theoretical differentiation between probabilistic and value-based expectation. | “To expect and to hope are different from each other. You can hope for a lot more than expect. To expect is more realistic.” (ID: 1009) |

|

| Aspect 4: comparison of two different versions of exemplary items: change question or statement formulation. | “The phrasing of 24a triggers burdens when you’re at the beginning of the treatment, 24b doesn’t trigger burdens.” (ID: 1005) Commentary about item (24a) vs (24b): (24a) I expect to be burdened by the treatment. (24b) How much burden do you expect your treatment will cause? |

|

| ||

| Item-level criticism: commentary on the content or wording of specific items. | “Item sounds like it is just for psychotherapy.” (ID: 1007) Commentary about item 15: I expect to take part more actively in social life due to treatment. |

|

| ||

|

The Treatment Expectation Questionnaire

After completion of the aforementioned steps of gathering empirical evidence, the construction of the initial TEX-Q version was accomplished in a final item selection process. It contains 35 items on the 10 different subscales derived from our theoretical model, with 3–4 items in each subscale. Every item contains either the verb to expect, to hope or to fear, and is formulated as a question asking for the amount of change the patients expect to experience following their treatment. Each item is presented on a 10-point Likert scale with specific anchors, the lower anchor always indicating no expected change. Example items for each subscale of the TEX-Q in preliminary translation are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Illustrative TEX-Q items for each subscale

| Expected benefits | ||||||||||||

| How much relief in your symptoms do you expect from the treatment? | ||||||||||||

| No relief | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Complete relief |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Expected positive impact | ||||||||||||

| How much improvement do you expect in your ability to do your daily activities (eg, occupation, household, social life)? | ||||||||||||

| No improvement | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Complete improvement |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Expected harm | ||||||||||||

| To what extent do you expect risks from your treatment? | ||||||||||||

| No risks | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extreme risks |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Expected negative impact | ||||||||||||

| How much do you expect the treatment will reduce your quality of life? | ||||||||||||

| Not at all | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extremely |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Desired benefits | ||||||||||||

| How much benefit do you hope for from the treatment? | ||||||||||||

| No benefit | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extreme benefit |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Desired impact | ||||||||||||

| How much improvement do you hope for considering your emotional state? | ||||||||||||

| No improvement | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extreme improvement |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Feared harm | ||||||||||||

| To what extent do you fear risks from the treatment? | ||||||||||||

| No risk | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extreme risk |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Feared negative impact | ||||||||||||

| How much do you fear the treatment will limit your day-to-day responsibilities (eg, at home, at work, in the family)? | ||||||||||||

| Not at all | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extremely |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Process-related expectations | ||||||||||||

| To what extent do you expect to be satisfied with the treatment procedure or process? | ||||||||||||

| Not at all | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extremely |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Expected behavioural control of the treatment | ||||||||||||

| To what extent do you expect your own behaviour to influence the success of the treatment? | ||||||||||||

| Not at all | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | Extremely |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

TEX-Q, Treatment Expectation Questionnaire.

Discussion

This study describes the successful development of the TEX-Q, a new scale for generically and multidimensionally measuring expectations of medical or psychological treatments. To accomplish this, an elaborate development process was necessary that incorporated the complex and diverse literature and evidence on expectations. The final TEX-Q will be available in German and English after psychometric evaluation. The scale is based on a comprehensive review of literature that provided an overview of existing treatment expectation scales and items. The evidence gathered from the review empirically validated our integrative model of expectations18 as well as our conceptualisation for the TEX-Q with 10 subdimensions derived from it. In line with our results, our model has further been empirically supported by a recent systematic review of expectation measurement in orthopaedic surgery.33 Few generic multidimensional scales, but several good treatment-specific measures were found and served as a source for our items. These items were modified and reformulated in the course of the development of the scale. This was informed by feedback from external experts in the field of placebo, psychosomatic and clinical psychology research and by patient feedback.

The TEX-Q has advantages over previous measures of treatment expectations. Its fully generic nature enables the comparability of assessments across different treatments and conditions. It thus presents an advantage over treatment-specific measurements as well as generic scales with limited scope, such as scales limited to psychotherapy,34 35 scales solely focusing expectations regarding symptoms (ie, pain), but not expectations regarding a broader impact on life (ie, quality of life).36 37 It furthermore has a theory-based, multidimensional structure, covering different aspects of treatment expectations about symptom change, possible adverse events and the broader impact of the treatment and its process. This distinguishes the TEX-Q from established generic instruments like the Questionnaire for Patient Expectations of Health Care,16 which mostly focuses on expectations about the structure and process of the treatment process, or the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire,38 and the newly developed Expectation for Treatment Scale,39 which only assesses positive outcome expectations.

Several issues within the development process need to be considered. A major challenge of developing a generic measure of treatment expectations was that it was impossible, at least empirically, to take every possible medical application specifically into account. While the scale could be developed and tested in a variety of different clinical settings, involving different surgical as well as psychological treatments, further settings, like pharmacological or physical therapy treatments, could have been beneficial. The development might therefore have been shaped by the treatments of patients interviewed, as well as other conditions of the development process, such as the limited scope of the research team or the experts involved for feedback. In future, we will test the TEX-Q in additional clinical settings to further broaden the empirical basis for the argument of the generic applicability of the TEX-Q. Other important limitations lie on the conceptual level. Our item phrasing is ambiguous with regard to two different aspects of expectations, assessing the magnitude of an expected change as well as the expected probability of its occurrence to some extent. The relevance of this differentiation was pointed out in the integrative model of expectations18 and is further supported by recent empirical evidence.40 Based on Kirsch’s22 theoretical considerations regarding the probabilistic nature of non-volitional expectations, and on Sherman et al’s41 indepth analysis of patients’ understanding of treatment expectations, our phrasing aimed to capture best both aspects of magnitude and probability. To prevent ambiguity, each of these aspects could have been assessed in a separate item (eg, ‘How likely do you think your symptoms will improve?’ and ‘How much improvement do you expect?’), but we refrained from it for the sake of our scale’s brevity and applicability. This may lead to differences in individual interpretations of our items and thereby lower their quality. Furthermore, although the theory-based construction of the questionnaire grounded in the integrative model of expectations18 provided a valuable framework for its subdimensions, it may thereby also have led to the exclusion of additional dimensions that could have emerged in a purely empirical concept development. Furthermore, expectation constructs mentioned by some authors had to be excluded from the TEX-Q for the sake of feasibility and applicability. Especially the work of Bowling et al16 is to be mentioned here, whose focus on treatment process expectations allowed them a more nuanced assessment, for example including items on expectations about the doctor–patient communication style or information provision. Another aspect is the exclusion of expectations about the timeline of the treatment and effects caused by it, for example, their duration and sustainability. While it was hoped initially the TEX-Q could measure such expectations, it was not feasible at the item level to ask for the many possible treatment trajectories.

The development of the TEX-Q facilitates a broad range of possibilities for future research, both in the evaluation and further development of the scale itself, as well as its use in applied research. Further validation of the scale in different clinical settings is necessary to confirm the psychometric properties of the TEX-Q and possibly further reduce its number of items. Therefore, the psychometric evaluation with patients from four different clinical settings will be published elsewhere. Other planned steps include the development of a brief version, evaluation of sensitivity to change and translation of the scale into other languages. An important contribution of the TEX-Q is that it will enable a comparison of the data gathered across studies on different conditions and treatments. Thereby, it will produce integrated evidence leading to further knowledge about the role of patients’ treatment expectations. Furthermore, the subscales of the TEX-Q can be used to further differentiate the effects of the aspects of treatment expectations between conditions and treatment outcomes. The knowledge gained can also contribute to the development of interventions designed to use expectation-related placebo effects to improve outcomes of everyday clinical practices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating patients for their valuable contribution to the development of the TEX-Q. We are grateful to Jasmin Conradi, Stephanie Assaker and all expert colleagues for their support in the scale development.

Footnotes

Twitter: @keithpetrie

Contributors: JA and MS-M were involved in the conception of the scale, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the first draft and revision. BL, KP and JL were involved in conception of the scale, data interpretation and revising the manuscript. MAG was involved in data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and revising the manuscript. YN was involved in scale conception, data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Medical Faculty Young Researchers Fund, Hamburg University, Germany (PI: MS-M, grant number NWF-18/10).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Chamber Hamburg, Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon reasonable request. Data sets and statistical codes are available from the Figshare repository at https://figshare.com/projects/TEX-Q/72347.

References

- 1.Mondloch MV, Cole DC, Frank JW. Does how you do depend on how you think you’ll do? A systematic review of the evidence for a relation between patients’ recovery expectations and health outcomes. CMAJ 2001;165:174–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rief W, Glombiewski JA, Gollwitzer M, et al. Expectancies as core features of mental disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2015;28:378–85. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Constantino MJ, Arnkoff DB, Glass CR, et al. Expectations. J Clin Psychol 2011;67:184–92. 10.1002/jclp.20754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enck P, Bingel U, Schedlowski M, et al. The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013;12:191–204. 10.1038/nrd3923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colagiuri B, Zachariae R. Patient expectancy and post-chemotherapy nausea: a meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 2010;40:3–14. 10.1007/s12160-010-9186-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones F, Riazi A. Self-efficacy and self-management after stroke: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:797–810. 10.3109/09638288.2010.511415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, et al. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1273–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Akker-Scheek I, Stevens M, Groothoff JW, et al. Preoperative or postoperative self-efficacy: which is a better predictor of outcome after total hip or knee arthroplasty? Patient Educ Couns 2007;66:92–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smeets RJEM, Beelen S, Goossens MEJB, et al. Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain 2008;24:305–15. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318164aa75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auer CJ, Glombiewski JA, Doering BK, et al. Patients’ expectations predict surgery outcomes: a meta-analysis. Int J Behav Med 2016;23:49–62. 10.1007/s12529-015-9500-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juergens MC, Seekatz B, Moosdorf RG, et al. Illness beliefs before cardiac surgery predict disability, quality of life, and depression 3 months later. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:553–60. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shedden Mora M, Nestoriuc Y, Rief W. Lessons learned from placebo groups in antidepressant trials. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011;366:1879–88. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nestoriuc Y, von Blanckenburg P, Schuricht F, et al. Is it best to expect the worst? influence of patients’ side-effect expectations on endocrine treatment outcome in a 2-year prospective clinical cohort study. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1909–15. 10.1093/annonc/mdw266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nestoriuc Y, Orav EJ, Liang MH, et al. Prediction of nonspecific side effects in rheumatoid arthritis patients by beliefs about medicines. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:791–9. 10.1002/acr.20160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hartingsveld F, Ostelo RWJG, Cuijpers P, et al. Treatment-related and patient-related expectations of patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of published measurement tools. Clin J Pain 2010;26:470–88. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e0ffd3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowling A, Rowe G, Lambert N, et al. The measurement of patients’ expectations for health care: a review and psychometric testing of a measure of patients’ expectations. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:1–509. 10.3310/hta16300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zywiel MG, Mahomed A, Gandhi R, et al. Measuring expectations in orthopaedic surgery: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:3446–56. 10.1007/s11999-013-3013-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laferton JAC, Kube T, Salzmann S, et al. Patients’ expectations regarding medical treatment: a critical review of concepts and their assessment. Front Psychol 2017;8:233. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Wickiewicz TL, et al. Patients’ expectations of knee surgery. JBJS 2001;83:1005–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leedham B, Meyerowitz BE, Muirhead J, et al. Positive expectations predict health after heart transplantation. Health Psychol 1995;14:74–9. 10.1037/0278-6133.14.1.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maddux J. Expectations and health. Cambridge handbook of psychology. Health and Medicine 2007:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirsch I. Response expectancy as a determinant of experience and behavior. Am Psychol 1985;40:1189–202. 10.1037/0003-066X.40.11.1189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz DD. The common sense represen tation of illness danger. Medical psychology. New York: Pergamon, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron LD, Leventhal H. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. Psychology Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadyl J, McPherson K. Return to work after injury: a review of evidence regarding expectations and injury perceptions, and their influence on outcome. J Occup Rehabil 2008;18:362–74. 10.1007/s10926-008-9153-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haanstra TM, van den Berg T, Ostelo RW, et al. Systematic review: do patient expectations influence treatment outcomes in total knee and total hip arthroplasty? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:152. 10.1186/1477-7525-10-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beatty PC, Willis GB. Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opin Q 2007;71:287–311. 10.1093/poq/nfm006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Younger J, Gandhi V, Hubbard E, et al. Development of the Stanford expectations of treatment scale (SETS): a tool for measuring patient outcome expectancy in clinical trials. Clin Trials 2012;9:767–76. 10.1177/1740774512465064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarzer R. Optimism, vulnerability, and self-beliefs as health-related cognitions: a systematic overview. Psychol Health 1994;9:161–80. 10.1080/08870449408407475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. The general self-efficacy scale (GSE). Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 2010;12:329–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Optimism CCS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol 1985;4:219–47. 10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cortes A, Meints SM, Katz JN. Characterizing the use of expectations in orthopedic surgery research: a scoping review. ACR Open Rheumatol 2019;1:440–51. 10.1002/acr2.11054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norberg MM, Wetterneck CT, Sass DA, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Milwaukee psychotherapy expectations questionnaire. J Clin Psychol 2011;67:574–90. 10.1002/jclp.20781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulte D. Patients’ outcome expectancies and their impression of suitability as predictors of treatment outcome. Psychother Res 2008;18:481–94. 10.1080/10503300801932505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson ME, Brown JL, George SZ, et al. Multidimensional success criteria and expectations for treatment of chronic pain: the patient perspective. Pain Med 2005;6:336–45. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagé MG, Ziemianski D, Martel MO, et al. Development and validation of the treatment expectations in chronic pain scale. Br J Health Psychol 2019;24:610–28. 10.1111/bjhp.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2000;31:73–86. 10.1016/S0005-7916(00)00012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barth J, Kern A, Lüthi S, et al. Assessment of patients’ expectations: development and validation of the expectation for treatment scale (ETS). BMJ Open 2019;9:e026712. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devlin EJ, Whitford HS, Denson LA, et al. ‘Measuring up’: a comparison of two response expectancy assessment formats completed by men treated with radiotherapy for prostate cancer‘. J Psychosom Res 2020;132:109979. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherman KJ, Eaves ER, Ritenbaugh C, et al. Cognitive interviews guide design of a new CAM patient expectations questionnaire. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:39. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res 2006;60:631–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie K, et al. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health 2002;17:1–16. 10.1080/08870440290001494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dohnke B, Müller-Fahrnow W, Knäuper B. Der Einfluss von Ergebnis- und Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen auf die Ergebnisse einer rehabilitation nACh Hüftgelenkersatz. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie 2006;14:11–20. 10.1026/0943-8149.14.1.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laferton JAC, Shedden Mora M, Auer CJ, et al. Enhancing the efficacy of heart surgery by optimizing patients' preoperative expectations: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Am Heart J 2013;165:1–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Blanckenburg P, Schuricht F, Albert U-S, et al. Optimizing expectations to prevent side effects and enhance quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing endocrine therapy: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2013;13:426. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Powell R, Johnston M, Smith WC, et al. Psychological risk factors for chronic post-surgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain 2012;16:600–10. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirani SP, Patterson DLH, Newman SP. What do coronary artery disease patients think about their treatments? an assessment of patients’ treatment representations. J Health Psychol 2008;13:311–22. 10.1177/1359105307088133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tinsley H. Expectations about counseling: unpublished test manual. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, Department of Psychology, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchant-Haycox S, Liu D, Nicholas N, et al. Patients’ expectations of outcome of hysterectomy and alternative treatments for menstrual problems. J Behav Med 1998;21:283–97. 10.1023/A:1018721117588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gecht MR, Connell KJ, Sinacore JM, et al. A survey of exercise beliefs and exercise habits among people with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 1996;9:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Habibović M, Pedersen SS, van den Broek KC, et al. Monitoring treatment expectations in patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator using the EXPECT-ICD scale. Europace 2014;16:1022–7. 10.1093/europace/euu006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bos A, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B. Expectations of treatment and satisfaction with dentofacial appearance in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;123:127–32. 10.1067/mod.2003.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dougherty CM, Johnston SK, Thompson EA. Reliability and validity of the self-efficacy expectations and outcome expectations after implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation scales. Appl Nurs Res 2007;20:116–24. 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abrams K, Zvolensky MJ, Dorman L, et al. Development and validation of the smoking abstinence expectancies questionnaire. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:1296–304. 10.1093/ntr/ntr184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Carvalho Leite JC, Seminotti N, Fontoura Freitas P, et al. The psychosocial treatment expectations questionnaire (PTEQ) for alcohol problems. European J Psychol Asses 2011;27:228–36. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao JJ, Armstrong K, Farrar JT, et al. Acupuncture expectancy scale: development and preliminary validation in China. Explore 2007;3:372–7. 10.1016/j.explore.2006.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hüppe M, Klotz K-F, Heinzinger M, et al. Beurteilung Der perioperativen Periode durch Patienten Erste evaluation eines anästhesiologischen Nachbefragungsbogens. Anaesthesist 2000;49:613–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holmes SD, Fornaresio LM, Miller CE, et al. Development of the cardiac surgery patient expectations questionnaire (C-SPEQ). Qual Life Res 2016;25:2077–86. 10.1007/s11136-016-1243-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sigrell H. Expectations of chiropractic patients: the construction of a questionnaire. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2001;24:440–4. 10.1016/S0161-4754(01)32187-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moser DK, Riegel B, McKinley S, et al. The control attitudes scale-revised: psychometric evaluation in three groups of patients with cardiac illness. Nurs Res 2009;58:42. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181900ca0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones SMW, Lange J, Turner J, et al. Development and validation of the expect questionnaire: assessing patient expectations of outcomes of complementary and alternative medicine treatments for chronic pain. J Altern Complement Med 2016;22:936–46. 10.1089/acm.2016.0242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Razmjou H, Finkelstein JA, Yee A, et al. Relationship between preoperative patient characteristics and expectations in candidates for total knee arthroplasty. Physiother Can 2009;61:38–45. 10.3138/physio.61.1.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Axelrad KJ. Locus of control and causal attributions as they relate to expectations for coping with a heart attack. Los Angeles: California School of Professional Psychology, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomeé P, Währborg P, Börjesson M, et al. A new instrument for measuring self-efficacy in patients with an anterior cruciate ligament injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:181–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tashjian RZ, Bradley MP, Tocci S, et al. Factors influencing patient satisfaction after rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007;16:752–8. 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noble PC, Scuderi GR, Brekke AC, et al. Development of a new knee Society scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:20–32. 10.1007/s11999-011-2152-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O’Malley KJ, Roddey TS, Gartsman GM, et al. Outcome expectancies, functional outcomes, and expectancy fulfillment for patients with shoulder problems. Med Care 2004;42:139–46. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108766.00294.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Habib SB, Sonoda L, See TC, et al. How do patients perceive the benefits and risks of peripheral angioplasty? implications for informed consent. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:177–81. 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohen L, de Moor C, Amato RJ. The association between treatment-specific optimism and depressive symptomatology in patients enrolled in a phase I cancer clinical trial. Cancer 2001;91:1949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036169supp001.pdf (680.9KB, pdf)