In outpatients with ulcerative colitis starting a new biologic agent, short disease duration was associated with higher risk of treatment failure and lower risk of achieving endoscopic remission, as compared with longer disease duration. This effect was primarily seen in biologic-naïve patients, but not biologic-experienced patients. These findings suggest that requirement of biologic therapy early in the course of disease may be a negative prognostic marker in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Keywords: Disease duration, prognosis, treatment failure, IBD

Abstract

Background

Longer disease duration is associated with inferior response to biologic therapy in Crohn’s disease. However, the effect of disease duration on response to biologic therapy in ulcerative colitis (UC) has not been well studied.

Methods

In a single-center retrospective cohort study of outpatients with UC starting a biologic agent, we evaluated treatment response by disease duration. The primary outcome was treatment failure (composite outcome of inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]–related surgery/hospitalization or treatment modification including dose escalation, treatment discontinuation, or addition of corticosteroids); secondary outcomes were risk of IBD-related surgery/hospitalization and endoscopic remission. We conducted multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses to evaluate the independent impact of disease duration on clinical outcomes.

Results

We included 160 biologic-treated UC patients (73% biologic-naïve) with a median age (interquartile range) of 36 (26–52) years and disease duration (range) of 4.5 (1–9) years. After adjusting for immunosuppressive medications, albumin, and body mass index, each 1-year increase in disease duration was associated with a 5% lower risk of treatment failure (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.91–0.99) and a 9% higher risk of achieving endoscopic remission (adjusted odds ratio, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01–1.18). This association of short disease duration with treatment failure was observed only in biologic-naïve patients, but not biologic-experienced patients. No significant association was seen between disease duration and risk of surgery or hospitalization.

Conclusion

Shorter disease duration is independently associated with increased risk of treatment failure in biologic-treated patients with UC. Requirement of biologic therapy early in the course of disease may be a negative prognostic marker in patients with UC.

INTRODUCTION

Several disease-related prognostic factors have been studied in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and frequently overlap with factors identified in Crohn’s disease (CD). However, unlike in CD, the impact of disease duration on response to therapy has not been well studied in patients with UC.1, 2 Disease duration has been consistently associated with response to different biologic agents in patients with Crohn’s disease. Suboptimally treated inflammatory CD may progress to fibrostenotic and penetrating complications that are not responsive to medical management; hence, early initiation of biologic therapy is more effective and is recommended in patients with CD.3 Over the last decade, treatment targets in UC have evolved from focusing on symptomatic remission toward achieving mucosal healing, which has been associated with a decrease in risk of colectomy.4 Population-based cohort studies have demonstrated a decline in colectomy rates with increasing use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α antagonists.5, 6 However, whether the timing of initiation of biologic therapy impacts its effectiveness in patients with UC is unknown. Unlike CD, UC is primarily a luminal disease with mucosal inflammation, although long-term inadequate control of disease may result in mural changes and submucosal fibrosis. It is unclear whether timing of biologic therapy may influence its effectiveness. Prior small retrospective studies or post hoc analyses of clinical trials have variably demonstrated either no association between disease duration and response to biologic therapy or higher risk of treatment failure in patients with short disease duration at the time of starting biologic therapy.7–11

Hence, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of biologic-treated patients with UC to understand how disease duration may impact treatment response, achieving endoscopic remission, and risk of colectomy and/or hospitalization in biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study in biologic-treated patients with UC seen and followed at the University of California San Diego (UCSD). Patients were included if they had UC, were new users of any biologic agent (TNFα antagonists such as infliximab, adalimumab or golimumab, or an anti-integrin agent such as vedolizumab) started at conventional Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved doses and regimens between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2016, and were followed at UCSD for at least 6 months. Patients were excluded if they (a) had Crohn’s disease or indeterminate colitis, (b) were not treated with biologic agents or biologics were initiated as during inpatient hospitalization for acute severe UC, (c) were followed at UCSD for <6 months, (d) were pregnant, or (e) had already undergone colectomy before starting biologic therapy. As patients hospitalized with acute severe ulcerative colitis represent a distinct set of patients with known poor prognosis, with high rates of treatment failure and short-term colectomy, we opted to exclude them to avoid confounding by disease severity. Prevalent users of biologic agents (ie, patients who were already on a biologic agent at the time of the study start date) were also excluded to minimize immortal time bias. This study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board (IRB #160967).

Data Abstraction

A single reviewer abstracted data through medical record review using a piloted data abstraction form, in consultation with a second gastroenterologist reviewer. Besides exposure and outcomes (as detailed below), data on the following variables were abstracted: (a) patient characteristics—age, sex, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI) at time of starting new biologic therapy; (b) disease characteristics—disease extent, disease duration, endoscopic disease activity at the time of starting a biologic agent, classified by Mayo endoscopy score, laboratory variables including hemoglobin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, albumin, and C-reactive protein at time of starting the biologic agent, prior hospitalization within 1 year of cohort entry; (c) treatment characteristics—current index biologic agent, prior use of immunomodulators and other biologic agents, prior use of corticosteroids within the past year, concurrent therapy with immunomodulators and/or corticosteroids; and (d) outcomes—date of IBD-related surgery, hospitalization, dose escalation, treatment discontinuation and addition of corticosteroids, and endoscopic re-assessment after starting biologic therapy.

Exposure

The primary predictor variable was disease duration as a continuous variable. We evaluated the association between each 1-year increase in disease duration and clinical outcomes. Secondary analysis using disease duration (<2 years vs ≥2 years) as a categorical predictor variable was also performed.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was time to treatment failure, a composite outcome of IBD-related surgery, hospitalization, or treatment modification (including index biologic dose escalation beyond FDA-approved dosing regimen, drug discontinuation, or addition/continuation of corticosteroids ≥3 months after starting index biologic therapy). Secondary outcomes of interest were time to IBD-related surgery (ileal pouch anal anastomosis, ileorectal anastomosis, or colectomy with end ileostomy), time to IBD-related hospitalization (primary discharge diagnosis of UC flare), or achieving endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopy subscore of 0 or 1, based on review of endoscopy reports performed by study IBD specialists) within 1 year of starting biologic therapy. Patients were followed from time of starting biologic therapy until occurrence of study outcome or definitive colectomy surgery (all other outcomes were considered independently), loss to follow-up, treatment interruption for >6 months, or study completion (December 31, 2016).

Statistical Analysis

We performed univariate time-to-event analysis or logistic regression (for endoscopic remission outcome) to evaluate the association between disease duration and clinical outcomes. To evaluate the independent effect of disease duration on response to biologic therapy, we performed multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses with a combination of backward variable selection (P < 0.15 in univariate analysis among age, sex, BMI, disease duration, disease extent, C-reactive protein, prior and concomitant use of steroids and/or immunomodulators) and inclusion of clinically relevant variables (albumin as a continuous variable [per 1 g/dL], prior anti-TNF failure for all outcomes; in addition, for hospitalization outcome, prior hospitalization within 1 year of cohort entry). To meet the assumption of normality, we performed a logarithmic transformation of the variable for disease duration and performed our analysis using the logarithmically transformed variable. The proportional hazard assumption was met based on graphical evaluation and examining weighted residuals.

All outcomes were analyzed in all biologic-treated patients, and subsequently stratified by biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients. To evaluate whether disease duration may differentially impact response to TNFα antagonists vs vedolizumab, we performed stratified analysis by drug type. Our sample was a convenient consecutive sample, starting from the time the IBD center was established at our hospital. No formal sample size assessment was performed.

All hypothesis testing was performed using a 2-sided P value with a statistical significance threshold <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata MP (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of 160 patients with UC who formed the study cohort. The median age of cohort (interquartile range [IQR]) was 36.0 (26.0–51.8) years, with 80 males and 80 females. Forty-three patients (27%) had a disease duration <2 years at the time of initiation of biologic agents. The median BMI (IQR) was 24.3 (21.4–28.7), and 18.1% were obese. Approximately 61% of patients had pancolitis, and 53% had severely active endoscopic disease. Approximately 73% of patients were biologic-naïve at the time of cohort entry, 55% were treated with infliximab, and 18.8% were treated with vedolizumab. About 53% and 52% were concomitantly on immunomodulators and corticosteroids, respectively, and 81% had used corticosteroids in the year before initiation of biologic therapy. Over a median follow-up of 2 years after starting biologic therapy, 110 patients experienced treatment failure, 23 patients underwent surgery, and 41 patients experienced IBD-related hospitalization. All patients with “treatment failure” underwent treatment modification as the primary reason for treatment failure; within treatment modification, initiation of corticosteroids was the most common intervention. These have been detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Biologic-Treated Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Included in the Cohort by Disease Duration

| Baseline Characteristics | All Patients | <2 y | ≥2 y | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 160 | 43 | 117 | - |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age at cohort entry, median (IQR), y | 36.0 (26.0–51.8) | 37.0 (23.0–51.0) | 40.2 (37.3–43.2) | 0.33 |

| Sex, males (%) | 50 | 49 | 50 | 0.89 |

| Disease duration, median (IQR), y | 4.5 (1.0–9.0) | N/A | N/A | - |

| Follow-up, median (IQR), mo | 24.0 (14.8–34.7) | 22.1 (14.4–24.7) | 28.6 (25.6–31.6) | <0.01 |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 24.3 (21.4–28.7) | 24.6 (21.5–28.7) | 25.8 (24.7–27.0) | 0.70 |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||

| •Current smokers | 8 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (6.8) | 0.03 |

| •Recent past smoker (<1 y from cohort entry) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | |

| •Former smokers | 39 (24.4) | 16 (37.2) | 23 (19.7) | |

| •Never smoker | 111 (69.4) | 26 (60.5) | 85 (72.7) | |

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| Disease extent, No. (%) | ||||

| •Extensive colitis | 98 (61.3) | 27 (62.8) | 71 (60.7) | 0.82 |

| •Left-sided colitis | 61 (38.1) | 16 (37.2) | 45 (38.5) | |

| •Proctitis | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Disease severity, No. (%) | ||||

| •Mayo score 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0.93 |

| •Mayo score 1 | 10 (9.8) | 3 (10.3) | 7 (9.6) | |

| •Mayo score 2 | 27 (36.3) | 11 (37.9) | 26 (35.6) | |

| •Mayo score 3 | 54 (52.9) | 15 (51.7) | 39 (53.4) | |

| Prior IBD hospitalization <1 y from cohort entry (%) | 44 (27.5) | 14 (32.6) | 30 (25.6) | 0.39 |

| Treatment characteristics | ||||

| TNFα antagonists taken at cohort entry, No. (%) | ||||

| •Infliximab | 88 (55.0) | 27 (62.8) | 61 (52.1) | 0.74 |

| •Adalimumab | 31 (19.4) | 8 (18.6) | 23 (19.7) | |

| •Golimumab | 10 (6.3) | 2 (4.7) | 8 (6.8) | |

| •Certolizumab pegol | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| •Vedolizumab | 30 (18.8) | 6 (13.9) | 24 (20.5) | |

| No. prior TNFα antagonist failures | ||||

| •0 | 117 (73.1) | 34 (79.1) | 83 (70.9) | 0.64 |

| •1 | 34 (21.3) | 8 (18.6) | 26 (22.2) | |

| •2 | 8 (5.0) | 1 (2.3) | 7 (6.0) | |

| •3 | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Prior steroid use <1 y from cohort entry, No. (%) | 130 (81.3) | 41 (95.4) | 89 (76.1) | <0.01 |

| Steroid use at cohort entry, No. (%) | 83 (51.9) | 27 (62.8) | 56 (47.9) | 0.09 |

| Prior use of immunomodulators, No. (%) | 85 (53.1) | 19 (44.2) | 66 (56.4) | 0.17 |

| Immunomodulator use at cohort entry, No. (%) | ||||

| •Azathioprine | 54 (60.7) | 16 (69.6) | 38 (57.6) | 0.34 |

| •6-mercaptopurine | 26 (29.2) | 4 (17.4) | 22 (33.3) | |

| •Methotrexate | 9 (10.1) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (9.1) | |

| CRP, median (IQR), mg/dL | 0.30 (0.10–1.40) | 0.50 (0.15–1.95) | 0.30 (0.10–1.30) | 0.18 |

| Albumin, median (IQR), g/dL | 4.10 (3.75–4.30) | 4.00 (3.70–4.30) | 4.10 (3.80–4.30) | 0.33 |

| Hgb, mean (SD), g/dL | 12.3 (2.1) | 11.8 (1.8) | 12.4 (2.2) | 0.14 |

| ESR, median (IQR), mm/h | 15.0 (6.3–28.0) | 18.0 (11.0–28.0) | 15.0 (6.0–28.0) | 0.58 |

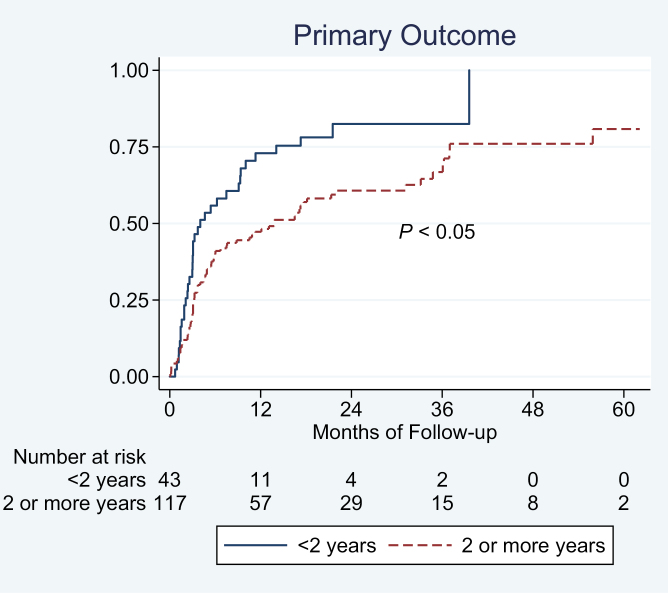

Primary Outcome

Using time-to-event analysis, shorter disease duration (<2 years) was associated with a higher risk of treatment failure in all biologic-treated patients with UC (Fig. 1). On multivariate analysis, adjusting for prior corticosteroid and TNFα antagonist exposure, concomitant immunomodulator use, albumin, disease extent, and body mass index, each 1-year increase in disease duration was associated with a 5% lower risk of treatment failure (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91–0.99) (Table 2). On categorical analysis, longer disease duration (≥2 y) was independently associated with a 23% lower risk of treatment failure (aHR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.60–0.98). Besides disease duration, low albumin was associated with treatment failure.

FIGURE 1.

Association between disease duration and risk of treatment failure in biologic-treated patients with UC.

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Analysis Examining Factors Associated With Treatment Failure in Biologic-Treated Patients With Ulcerative Colitis

| Variables | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior TNFα antagonist exposure (yes vs no) | 0.75 | 0.46–1.23 | 0.25 |

| Disease duration (per 1 y) | 0.95 | 0.91–0.99 | 0.016 |

| Body mass index (per 1-kg/m2 increase) | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | 0.047 |

| Concomitant immunomodulators (yes vs no) | 0.65 | 0.41–1.02 | 0.063 |

| Albumin (per 1 g/dL) | 0.66 | 0.45–0.99 | 0.045 |

| Prior prednisone use (yes vs no) | 1.85 | 0.93–3.67 | 0.078 |

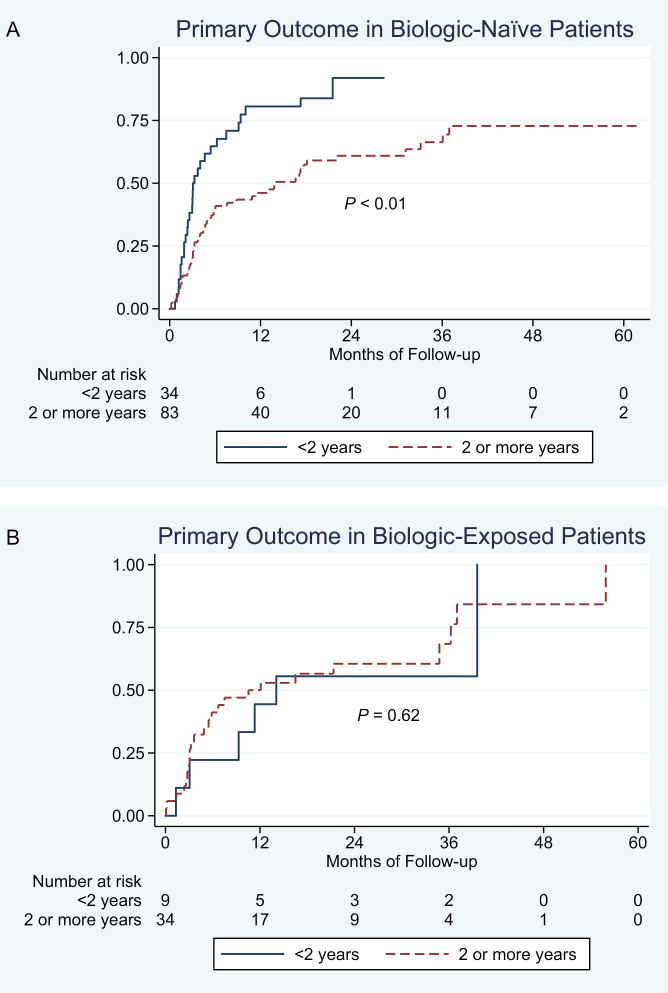

Biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients

Approximately 29% of biologic-naïve patients (34/117) and 21% of biologic-experienced patients (9/43) had a short disease duration at the time of starting biologic therapy. The negative impact of disease duration on response to biologic therapy was strongest in biologic-naïve patients (Fig. 2A); in patients with prior biologic exposure, disease duration did not significantly impact response to second- or third-line biologic therapy (Fig. 2B). On multivariate analysis, in biologic-naïve patients, longer disease duration (≥2 y) was independently associated with a 46% lower risk of treatment failure (aHR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.32–0.90) (Supplementary Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Association between disease duration and risk of treatment failure in (A) biologic-naïve and (B) biologic-experienced patients with UC.

Type of biologic agent

On stratifying by type of biologic agent, longer disease duration was associated with lower risk of treatment failure in TNFα antagonist–treated patients (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Disease duration was not associated with treatment response in vedolizumab-treated patients with UC on univariate analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1B); due to the small number of vedolizumab-treated patients, multivariate analysis was not performed.

Secondary Outcomes

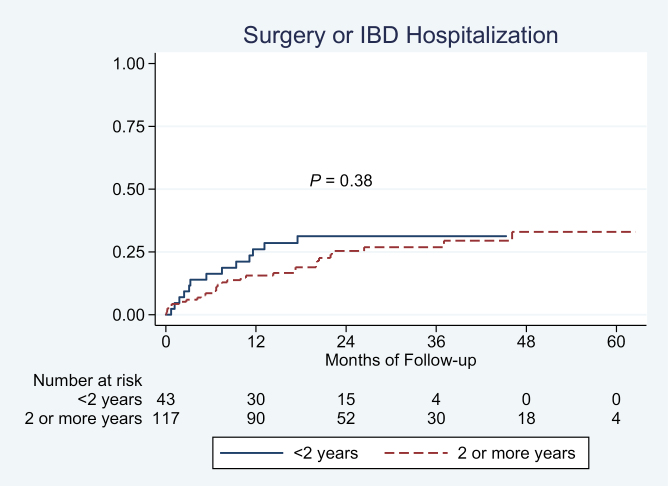

Surgery and/or hospitalization

Disease duration was not significantly associated with risk of surgery and/or hospitalization on univariate (Fig. 3) or multivariate analysis (odds ratio [OR] per 1 year of disease duration, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.93–1.07).

FIGURE 3.

Association between disease duration and risk of UC-related surgery or hospitalization in biologic-treated patients with UC.

Endoscopic remission

On multivariate logistic regression analysis, each 1-year increase in disease duration was associated with 9% higher odds of achieving endoscopic remission (adjusted OR [aOR], 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01–1.18) (Table 3). Among biologic-naïve patients, longer disease duration (≥2 years) was associated with a numerically higher odds of achieving endoscopic remission (aOR, 2.59; 95% CI, 0.90–7.44), though this was not statistically significant. In contrast, among biologic-experienced patients, longer disease duration was not associated with higher odds of achieving endoscopic remission (aOR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.08–9.64).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis Examining Factors Associated With Achieving Endoscopic Remission in Biologic-Treated Patients With Ulcerative Colitis

| Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior TNFα antagonist exposure (yes vs no) | 0.83 | 0.32–2.14 | 0.71 |

| Body mass index (per 1-kg/m2 increase) | 0.93 | 0.87–1.00 | 0.056 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.12 |

| Albumin (per 1 g/dL) | 2.26 | 0.91–5.59 | 0.079 |

| Disease duration (per 1 y) | 1.09 | 1.01–1.18 | 0.036 |

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study on the impact of disease duration on treatment response and outcomes in 160 biologic-treated patients with UC, we observed that short disease duration is independently associated with an increased risk of treatment failure and lower likelihood of achieving endoscopic remission. Short disease duration at the time of biologic initiation was not associated with increased risk of IBD-related surgery and/or hospitalization. When stratified by biologic-naïve vs biologic-experienced patients, short disease duration was associated with increased risk of treatment failure only in biologic-naïve patients, not in biologic-experienced patients. Our findings suggest that early need for biologic therapy may be an independent negative prognostic factor in patients with UC, regardless of inflammatory burden, disease extent, or albumin. These patients may require closer proactive monitoring and aggressive treatment to decrease risk of treatment failure.

Several patient-related (high body mass index), disease-related (severe endoscopic activity, more extensive disease, elevated inflammatory biomarkers, low albumin), and treatment-related characteristics (low trough concentration, antidrug antibodies, lack of concomitant immunomodulators) have been associated with inferior response to biologic therapy in patients with UC.12 However, the impact of disease duration at the time of starting biologic therapy has not been well studied. In post hoc analysis of ULTRA clinical trials of adalimumab for moderately to severely active UC, Sandborn and colleagues observed no difference in the risk of achieving clinical remission in patients with short (≤2 years) vs long (>2 years) disease duration13; subsequent analysis showed a lower risk of colectomy with longer disease duration in adalimumab-treated patients with UC.7 In a retrospective cohort study of 190 infliximab-treated patients with corticosteroid-dependent or -refractory patients, Murthy and colleagues observed a lower risk of infliximab failure and colectomy with longer disease duration; however, 35% of their cohort included patients with corticosteroid-refractory, hospitalized acute severe UC, patients who are intrinsically at significantly higher risk of colectomy.11 In contrast, Ma and colleagues observed that early use of TNFα antagonists was not associated with increased risk of surgery, hospitalization, or secondary loss of response, despite these patients having more severe endoscopic disease at baseline.9 Although our study was not adequately powered to evaluate the association between disease duration and response to vedolizumab, similar results have been reported for vedolizumab in patients with UC. In the multicenter VICTORY consortium, Faleck and colleagues observed that disease duration was not associated with risk of achieving clinical remission, corticosteroid-free remission, or mucosal healing.8 In a subsequent validated prediction model for response to vedolizumab in patients with moderately to severely active UC, using data from the phase III GEMINI 1 clinical trial, Dulai and colleagues observed that disease duration ≥2 years was independently predictive of achieving corticosteroid-free clinical remission by week 26.14

Caution needs to be exercised in interpreting these findings. Due to the noninterventional nature of these studies, with lack of randomization, our study does not address or interpret the role of “step-up” vs “top-down” therapy for UC. A blinded randomized trial, stratifying patients with moderately to severely active UC based on disease duration (short vs long disease duration) to either “step-up” or “top-down” therapy will address that question. Rather, our findings suggest that patients whose disease warrants initiation of biologic agents within 2 years of UC diagnosis may have higher rates of treatment failure, perhaps related to more severe disease not being adequately represented using conventional measures of disease severity. Biologically, patients with severe disease activity shortly after disease onset may have different inflammatory pathways with more active memory adaptive cells without any fatiguing of the immune response15; in effect, short disease duration may be a separate “clinical biomarker” of currently unmeasured biological factors.

Our study is one of the largest studies evaluating the impact of disease duration on treatment response to biologics in patients with UC with systematic data collection and evaluation of patient-important outcomes. By limiting analyses to new users of biologics followed at our center, excluding patients with acute severe UC, and by adjusting for key confounders, we were able to mitigate the potential limitations of a tertiary referral center retrospective cohort study. However, our study has some limitations that merit attention. First, though we adjusted for typical clinical and biochemical markers of disease severity, we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured confounders. In fact, we believe that our findings likely represent confounding by disease severity, wherein biologic agents are started early in the disease course only in a subset of patients at high risk of adverse outcomes. Second, findings on subgroup analysis, particularly on the impact of disease duration on response to vedolizumab, should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of patients. As noted above, the VICTORY consortium, which includes vedolizumab-treated patients from our center, has already addressed this association comprehensively. Due to the recency of its approval, we could not ascertain the impact of disease duration on response to tofacitinib, and this will be addressed in an upcoming analysis of a multisite consortium of new users of tofacitinib in UC. Third, we were unable to evaluate the impact of obesity on achieving clinical remission or response based on validated disease activity indices in this retrospective study. Instead we relied on pragmatic clinically relevant outcomes including surgery, hospitalization, or need for treatment modification, which may be subject to provider preferences. The secondary outcomes including IBD-related surgery and/or hospitalization and achieving endoscopic remission, however, are more robust with limited risk of bias. All endoscopies at our center are performed by providers with a clinical and research focus on IBD, which decreases risk of misinterpretation.

Our findings have important clinical implications. In clinical practice, physicians may consider aggressive treatment and close proactive monitoring in patients with UC whose disease warrants early initiation of biologic agents. Some potential changes include potentially considering use of biologic agents in combination with immunomodulators and having a low threshold for monitoring postinduction biologic trough concentration. Ideally, to address the role of “step-up” vs “top-down” therapy for UC, a clinical trial with stratified randomization of patients with short and long disease duration, at similar levels of disease activity, to either “step-up” vs “top-down” therapy is warranted.

In conclusion, in a cohort of patients with UC starting a biologic agent, we observed that short disease duration is independently associated with increased risk of treatment failure and a lower risk of achieving endoscopic remission, particularly in biologic-naïve patients. This suggests that early need for biologic agents in routine practice in patients with UC may be a prognostic marker for adverse outcomes that warrants early recognition and an aggressive treatment approach.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Supported by: Dr. Nguyen is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; T32 DK007202). Dr. Dulai is supported by the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholar Award. Dr. Singh is supported by the NIH/NIDDK (K23DK117058), an American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award, and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award (#404614).

Conflicts of interest: S.S.: research grants from AbbVie; consulting fees from AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, AMAG Pharmaceuticals. N.H.N.: none to declare. S.K.: none to declare. B.S.B.: research grant from Prometheus Laboratories (owned by Precision IBD), consulting fees from Abbvie, Pfizer. P.S.D.: research support from Takeda, Pfizer, Abbvie, Janssen, Polymedco, ALPCO, Buhlmann; consulting fees from Takeda, Pfizer, Abbvie, Janssen. W.J.S.: research grants from Atlantic Healthcare Limited, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories (owned by Precision IBD); consulting fees from Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Avexegen Therapeutics, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Conatus, Cosmo, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Forbion, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Gossamer Bio, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Research, Landos Biopharma, Lilly, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Pfizer, Precision IBD (owns Prometheus Laboratories), Progenity, Prometheus Laboratories (owned by Precision IBD), Reistone, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials (owned by Health Academic Research Trust, HART), Series Therapeutics, Shire, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Sterna Biologicals, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences, Vivelix Pharmaceuticals; and stock or stock options from BeiGene, Escalier Biosciences, Gossamer Bio, Oppilan Pharma, Precision IBD (owns Prometheus Laboratories), Progenity, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences. Spouse: Opthotech: consultant, stock options; Progenity: consultant, stock; Oppilan Pharma: employee, stock options; Escalier Biosciences: employee, stock options; Precision IBD (also owns Prometheus Laboratories): employee, stock options; Ventyx Biosciences: employee, stock options; Vimalan Biosciences: employee, stock options.

Author contributions: Study concept and design: S.S. Acquisition of data: S.S., S.K. Analysis and interpretation of data: N.H.N., W.J.S., S.S. Drafting of the manuscript: S.S. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: N.H.N., S.K., B.S.B., P.S.D., W.J.S. Approval of the final manuscript: N.H.N., S.K., B.S.B., P.S.D., W.J.S., S.S. Guarantor of the article: Dr. Siddharth Singh had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, et al. . Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. . Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389:1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Danese S, Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Early intervention in Crohn’s disease: towards disease modification trials. Gut. 2017;66:2179–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. . Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eriksson C, Cao Y, Rundquist S, et al. . Changes in medical management and colectomy rates: a population-based cohort study on the epidemiology and natural history of ulcerative colitis in Örebro, Sweden, 1963-2010. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parragi L, Fournier N, Zeitz J, et al. ; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group Colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis are low and decreasing: 10-year follow-up data from the Swiss IBD Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Lazar A, et al. . Adalimumab therapy is associated with reduced risk of hospitalization in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:110–118.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Faleck DM, Winters A, Chablaney S, et al. . Shorter disease duration is associated with higher rates of response to vedolizumab in patients with Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(12):2497–2505.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, et al. . Similar clinical and surgical outcomes achieved with early compared to late anti-TNF induction in mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:2079582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mir SA, Nagy-Szakal D, Smith EO, et al. . Duration of disease may predict response to infliximab in pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murthy SK, Greenberg GR, Croitoru K, et al. . Extent of early clinical response to infliximab predicts long-term treatment success in active ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2090–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barré A, Colombel JF, Ungaro R. Review article: predictors of response to vedolizumab and ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. . Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:257–265.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dulai PS, Singh S, Vande Casteele N, et al. . Development and validation of a clinical scoring tool for predicting treatment outcomes with vedolizumab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:S67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kugathasan S, Saubermann LJ, Smith L, et al. . Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:1696–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.