During the study period, it was observed that the prevalence rates of anxiety, depression, and PTSD increased among veterans with IBD, whereas the incident rates, particularly depression, seemed to be declining.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, inflammatory bowel disease, veterans

Abstract

Background

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are more susceptible to mental health problems than the general population; however, temporal trends in psychiatric diagnoses’ incidence or prevalence in the United States are lacking. We sought to identify these trends among patients with IBD using national Veterans Heath Administration data.

Methods

We ascertained the presence of anxiety, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans with IBD (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease) during fiscal years 2000–2015. Patients with prior anxiety, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder before their first Veterans Health Administration IBD encounter were excluded to form the study cohort. We calculated annual prevalence, incidence rates, and age standardized and stratified by gender using a direct standardization method.

Results

We identified 60,086 IBD patients (93.9% male). The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and/or posttraumatic stress disorder increased from 10.8 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 38 per 100 with IBD in 2015; 19,595 (32.6%) patients had a new anxiety, depression, and/or posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis during the study period. The annual incidence rates of these mental health problems went from 6.1 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 3.6 per 100 in 2015. This trend was largely driven by decline in depression.

Conclusions

The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder is high among US veterans with IBD and increasing, given the chronicity of IBD and psychological diagnoses. Incidence, particularly depression, appears to be declining. Confirmation and reasons for this encouraging trend are needed.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a chronic and debilitating group of inflammatory conditions of the digestive system, includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Although the etiology is not well established, IBD is best conceptualized as a multifactorial disorder, which results from a complex interaction between genetic and environmental variables.1 The chronic and episodic nature of IBD is associated with impaired quality of life, and those with IBD are more susceptible to mental health problems than the general population.2 Research also suggests that mental health problems may precede IBD3 and are associated with clinical recurrence.4

Of the mental health problems, anxiety and depression are particularly elevated among patients with IBD.2, 5, 6 A Canadian study examined the 12-month prevalence of depression in a subset of people with IBD from 2 nationally representative surveys and found ranging prevalence from 14.7%–16.3%, which was approximately triple that of the general population.7 A subsequent Canadian study by Walker et al8 compared a cohort of IBD cases to a matched sample of community controls selected from a population-based national health survey who did not have IBD and found a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of major depression among IBD cases (27%) relative to the community controls (12%). An Australian study by Tribbick et al examined prevalence rates of anxiety and depressive disorders in an IBD tertiary care outpatient setting and found that 19.8% of patients with IBD had at least 1 anxiety condition and 11.1% had a depressive disorder.9 Byrne et al examined the point prevalence of anxiety and depression among patients with IBD attending a gastroenterology clinic at a tertiary academic hospital in Canada and found rates of depression and anxiety to be 25.8% and 21.2%, respectively.10 Despite these findings, it is difficult to compare prevalence rates of anxiety and depression across studies due to the significant variability in methodology used to assess diagnoses, sample selection, and the timeframe in which prevalence was assessed. Further, there have been no estimates of temporal trends in psychiatric diagnoses’ incidence or prevalence rates among a national cohort of patients with IBD within the United States.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States. Previously, our group identified a large and growing cohort of military veterans who suffer from IBD.11 However, it is unclear how many of these patients are experiencing mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression, which are common among patients with other chronic illnesses.12 Veterans in particular may be more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a related trauma and stressor-related disorder that has been shown to be associated with chronic health problems.13 The aim of this study was to identify temporal trends in incidence and prevalence of these mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD in this population of veteran patients with IBD. Identifying these comorbid mental health problems within this patient population would improve health care practices by helping providers streamline appropriate treatment options and address gastrointenstinal (GI) concerns and mental health difficulties simultaneously.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical Considerations

The institutional review boards of the Baylor College of Medicine and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas, approved this study.

Study Design and Data Source

This retrospective cohort study used data from the national VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) administrative data sets. The CDW comprises information on each patient’s inpatient and outpatient encounters from any facility in the VHA nationwide, including International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) codes.

Case Identification

We identified VHA users with IBD by our previously defined and validated algorithms for Crohn’s disease (555.x) or ulcerative colitis (556.x) of at least 2 codes, with at least 1 occurring from an outpatient encounter (positive predictive value of 0.87)11, 14 between fiscal years (FYs) 1998 and 2015. We identified using previous ICD-9 criteria of patients with new diagnoses of anxiety, depression, or PTSD in VHA outpatient facilities during the study period. New diagnoses are defined as no ICD-9 code specific to the mental health condition of interest within 6 months before the first date (index date) in the FY. We used the following codes for depression: codes 293.83, 296.20–296.36, 300.4, and 311. We used the following codes for anxiety: codes 293.84, 293.89, 300.00–300.02, 300.09, 300.20–300.23, 300.29, and 300.3. We used the following codes for PTSD: codes 308 and 309.81.15, 16 We retained patients with either depression, anxiety, or PTSD from FYs 2000 to 2015. We also excluded all individuals with a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or PTSD any time before their index IBD diagnosis from the study cohort to eliminate patients with preexisting mental health conditions.

Statistical Analyses

Prevalence and incidence rates were calculated for each mental health condition—depression, anxiety, or PTSD—and combined for all 3 mental health conditions. Age-standardized rates, stratified by gender to the base FY 2000, were calculated per FY. The study period of interest was FYs 2000 to 2015.

We calculated the crude annual prevalence as proportions of IBD patients with either anxiety, depression, or PTSD, or all 3 MH conditions combined, identified within each FY. We defined the numerator as the total number of IBD patients with either anxiety, depression, or PTSD cases during each FY and the denominator as the total number of IBD patients with at least 1 VA encounter during that FY.

We calculated the crude annual incidence rates for each mental health condition—depression, anxiety, or PTSD—and a combined rate for all 3 conditions. The numerator for these rates was the total number of newly identified cases for that specific mental health condition in a given FY, based on the presence of the ICD-9 code for mental health condition of interest in that year, among IBD patients with no previous diagnosis code for that specific mental health condition, as described in the previous section. The denominator for incidence rates served as an estimate of the at-risk population of VHA users with IBD in each FY with no prior mental health diagnosis for the given condition. We considered the total number of all VHA users with IBD in each FY, excluding those with any previous diagnosis for the specific mental health condition of interest (either anxiety, depression, or PTSD).

Subsequently, we standardized the calculated incidence and prevalence crude rates for possible temporal changes in the age distribution, stratified by gender of the underlying population, by applying the direct standardization method using the FY 2000 IBD cases in the VHA as the reference population. The rates were expressed per 100 veterans with IBD. The age groups were categorized into younger than 25, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and older than 85 years at IBD index, and gender was expressed as males vs female. Age-specific incidence rates were calculated for each FY. Incidence-rate ratios were also calculated, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing men and women. Age-standardized prevalence and incidence, stratified by gender, was then plotted, with FY 2000 as the base year.

RESULTS

In all, 77,906 cases of IBD were identified using the criteria described. Cases with a preexisting mental health diagnosis at IBD index (n = 17,820) were excluded, giving a final study cohort of 60,086 unique IBD cases. The identified IBD study cohort included patients with or without anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Inflammatory bowel disease with a mental health condition was defined as a case with an index mental health encounter occurring after the index IBD in FY 2000 to 2015. Among the 60,086 IBD cases, 93.9% were men; and the ethnic distribution was 74.2% white, 8.0% African American, 1.9% Hispanic, 1.4% other, and 14.5% in whom race could not be classified. A total of 50% were between the ages of 55 and 74 years at IBD index.

A total of 19,595 patients with a new diagnosis of mental health problems were identified among veterans with IBD during FY 2000 to 2015. The demographic features were not different from those of prevalent mental health cases. Of incident mental health patients, 91% were men; and the ethnic distribution was 75.7% white, 9.6% African American, 2.4% Hispanic, 1.7% other, and 10.6% in whom race could not be classified.

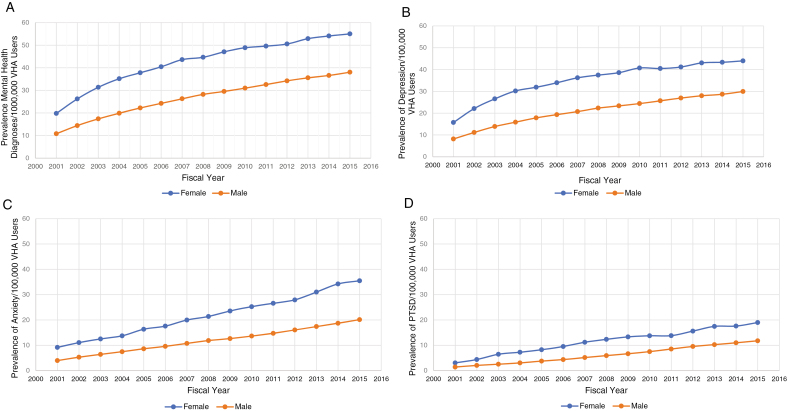

Standardized Prevalence Rates: Overall

Annual age-standardized prevalence rates of overall mental health diagnoses increased approximately 3.5-fold for male veterans, from 10.8 (95% CI) per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 38 per 100 with IBD in 2015. There was a slightly lower increase for female veterans, from 19.8 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 55 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A, Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of overall mental health diagnoses, stratified by gender. B, Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of depression, stratified by gender. C, Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of anxiety, stratified by gender. D, Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of posttraumatic stress disorder, stratified by gender.

Standardized Prevalence Rates: Depression

Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of depression increased approximately 3.75-fold for male veterans, from 8.2 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 30 per 100 with IBD in 2015. There was a slightly lower increase for female veterans, from 15.7 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 44 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 1B).

Standardized Prevalence Rates: Anxiety

Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of anxiety increased approximately 5-fold for male veterans, from 4 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 20 per 100 with IBD in 2015. The rates for female veterans increased slightly less, from 9.2 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 35.5 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 1C).

Standardized Prevalence Rates: PTSD

Annual age-standardized prevalence rates (base year of 2000) of PTSD increased substantially, approximately 8-fold, for male veterans from 1.4 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 11.8 per 100 with IBD in 2015. The rates for female veterans increased approximately 6-fold, from 3 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 19 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 1D).

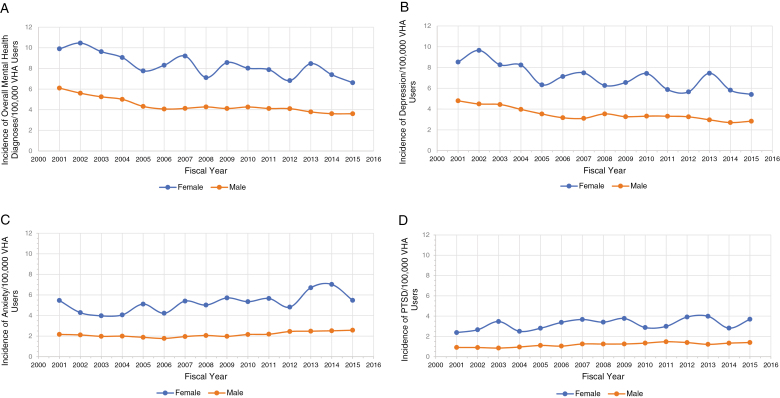

Standardized Incidence Rates: Overall

Annual age-standardized incidence rates of overall mental health (anxiety, depression, or PTSD) conditions varied for male veterans, from a high of 6.1 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to a low of 3.6 per 100 with IBD in 2015. The rates also varied for female veterans, from a high of 9.9 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to a low of 6.1 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 2A). The standardized incidence rates of overall mental health were higher in female patients than in male patients (incidence rate ratios, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.19–1.31).

Figure 2.

A, Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of overall mental health, stratified by gender. B, Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of depression, stratified by gender. C, Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of anxiety, stratified by gender. D, Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of PTSD, stratified by gender.

Standardized Incidence Rates: Depression

Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of depression varied for male veterans, from a high of 4.8 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to a low of 2.7 per 100 with IBD in 2014, followed by a slight increase to 2.8 per 100 with IBD in 2015. The rates also varied for female veterans, from 8.5 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to a high of 9.7 per 100 with IBD in 2002, back down to a low of 5.4 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 2B). The standardized incidence rates of depression were higher in female veterans than in male veterans (incidence rate ratios, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23–1.38).

Standardized Incidence Rates: Anxiety

Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of anxiety were stable for male veterans, ranging from 1.95 per 100 with IBD to 2.57 per 100 with IBD over the study period. However, the rates varied over time for female veterans, ranging from 4.06 per 100 with IBD to 7.02 per 100 with IBD over the study period (Fig. 2C). The standardized incidence rates of anxiety were higher in female veterans than in male veterans (incidence rate ratios, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.34–1.53).

Standardized Incidence Rates: PTSD

Annual age-standardized incidence rates (base year of 2000) of PTSD were stable over time for male veterans, ranging from 0.85 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 1.39 per 100 with IBD in 2015. However, the rates varied over time for female veterans, ranging from 2.37 per 100 with IBD in 2001 to 3.91 per 100 with IBD in 2015 (Fig. 2D). The standardized incidence rates of PTSD were higher in female veterans than in male veterans (incidence rate ratios, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.05–1.27).

Discussion

Our study expands upon previous research that examined temporal trends in IBD incidence and prevalence in a US national cohort of VHA users11 and represents the first report of descriptive epidemiology associated with anxiety, depression, and PTSD in this population. Among patients with IBD, we observed a progressive increase in prevalent cases for anxiety, depression, and/or PTSD during the study period. There was a downward trend in the incidence of mental health problems among men and women over time. This trend was largely driven by depression, as rates of anxiety and PTSD were stable for male veterans and varied for female veterans.

The finding that prevalent cases of mental health problems among patients with IBD increased over time supports previous literature that indicates that IBD patients are burdened by concomitant mental health problems.2 Depression, anxiety, and PTSD are highly prevalent among veterans in general; 17–19 however, when patients have psychiatric distress complicated by IBD, they may be particularly vulnerable to negative health outcomes. Psychiatric distress may impair health-related quality of life,20 precipitate IBD flares,21 increase health care costs and utilization,22 and complicate IBD management.23 Interestingly, prevalence rates of mental health problems had a slow and steady rise, which may be explained, in part, by the chronic and relapsing/remitting nature of IBD. Over time, patients with IBD may become more burdened and limited by IBD and susceptible to psychiatric distress. It is also possible that the increase in prevalence reflects an increase in the number of veterans who use the VHA in the United States to address mental health problems, given that people with anxiety and mood disorders often seek health care more frequently than others22 and that mental health treatments have become increasingly accessible in the VHA.16

We found that the standardized incidence and prevalence rates for anxiety, depression, and PTSD were consistently higher in women than in their male counterparts. Our findings align with the broader medical literature that anxiety and mood disorders are more common among women than men24, 25 and may reflect heightened levels of emotional stress associated with women’s military experience.26 However, more research needs to fully understand biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors that may be responsible for why women with IBD are prone to higher incident and prevalent rates of such mental health problems compared to men with IBD.

Interestingly, we observed a stable or decreased incidence of mental health diagnoses, particularly depression, among veterans with IBD. One possible reason for this observation is that improvements in IBD treatments helped individuals better manage their GI symptoms and have an improved functional status and quality of life, which consequently had a protective effect against the development of depressive symptoms. Other potential explanations for this observation may be related to increasing recognition and the corresponding increase in mental health resources provided by the VA during the study period.27 The VA health system is unique in its ready access to mental health resources relative to patients in commercial insurance, where patients may use out-of-pocket resources to obtain access to mental health providers, and therefore this data would not be captured using claims-based data sets.

Our study has several strengths. We used the VHA CDW data sets, which contain national data from which we could determine a basis of the overall burden of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among VHA users with IBD. This is the first study to examine these trends in a US-based population. We were also able to examine temporal trends of incidence and prevalence of mental health problems over several years, whereas prior studies provided only incidence and prevalence rates at a particular point in time.10 This study has limitations inherent to a large administrative data set; for example, our findings are based on the accuracy and completeness of ICD-9 coding. We did, however, validate a prior IBD cohort in the VHA, with a positive predictive value of 0.87.14 It is also impossible to determine whether the ICD-9 diagnoses align with Diagnostic & Statistical Manual-5 diagnoses or definitions for each patient. Furthermore, patients in our study population may not reflect the general IBD population, given the unique environmental exposure of veterans that may predispose them to mental health disorders and the large proportion of males in our data set. To enhance the generalizability of our findings, future studies should address the difference between anxiety, depression, and PTSD among veterans versus nonveterans with IBD and consider gender differences to clarify how these concomitant mental health problems differentially impact males and females with the disorder. We also did not compare our findings to a control group of patients without IBD; therefore, it is unclear how temporal trends of anxiety, depression, and PTSD differ among patients with and without IBD. Examining these differences would be an important avenue of future research. In addition, we did not examine the mechanisms responsible for our findings, which limits the ability to make recommendations about how to best use these data in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

We observed that the prevalence of mental health problems increased among veterans with IBD, whereas the incident rates decreased. It is clear that mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD, remain a burden among veterans with IBD; however, the impact and clinical implications of these disorders require further investigation. Future research is warranted to understand the role IBD plays in contributing to psychiatric distress and vice versa, as well as to identify potential etiologic factors associated with mental health problems in this population. Improving our understanding of these factors would then facilitate the development of more targeted pharmacological and behavioral treatments that could effectively address comorbid mental health difficulties among patients with IBD.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

- CDW

VHA Corporate Data Warehouse

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition codes

Notes

Author Contributions: JH, ERT, SS, and JK contributed to the study design, data analysis, and authorship of the manuscript. AW, JG, LAF, SG, LD, and HBE contributed to authorship and editorial input of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved of the final draft of the manuscript.

Supported by: The research reported here was supported in part with resources at the VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13–413), at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX (JKH) and NIH grant P30 DK56338, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (HES)

Conflicts of interest: JH has served as a speaker for Abbvie and Janssen and served as a consultant for Pfizer, Janssen, Daichii Sankyo, and Abbvie. JH has received research funding from Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer, Celgene, Eli-Lilly, and Redhill Biopharma. LAF has received research funding from Takeda, Inc. JRK has received research funding from Merck. The other authors have no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1. Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Graff LA, Walker JR, Bernstein CN. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: a review of comorbidity and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1105–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cawthorpe D, Davidson M. Temporal comorbidity of mental disorder and ulcerative colitis. Perm J. 2015;19:52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel JB, et al. ; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:829–835.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Häuser W, Janke KH, Klump B, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, et al. Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a literature review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuller-Thomson E, Sulman J. Depression and inflammatory bowel disease: findings from two nationally representative Canadian surveys. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walker JR, Ediger JP, Graff LA, et al. The Manitoba IBD cohort study: a population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1989–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tribbick D, Salzberg M, Ftanou M, et al. Prevalence of mental health disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: an Australian outpatient cohort. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Byrne G, Rosenfeld G, Leung Y, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:6496727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hou JK, Kramer JR, Richardson P, et al. The incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among U.S. veterans: a national cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1059–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009;190:S54–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McFarlane AC. The long-term costs of traumatic stress: intertwined physical and psychological consequences. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hou JK, Tan M, Stidham RW, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic codes for identifying patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2406–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cully JA, Jameson JP, Phillips LL, et al. Use of psychotherapy by rural and urban veterans. J Rural Health. 2010;26:225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mott JM, Hundt NE, Sansgiry S, et al. Changes in psychotherapy utilization among veterans with depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suris A, Lind L. Military sexual trauma: a review of prevalence and associated health consequences in veterans. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2008;9:250–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zatzick DF, Marmar CR, Weiss DS, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1690–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guthrie E, Jackson J, Shaffer J, et al. Psychological disorder and severity of inflammatory bowel disease predict health-related quality of life in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1994–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, et al. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1994–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Limsrivilai J, Stidham RW, Govani SM, et al. Factors that predict high health care utilization and costs for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:385–392.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evertsz FB, Thijssens NAM, Stokkers PC, et al. Do inflammatory bowel disease patients with anxiety and depressive symptoms receive the care they need? J Crohn’s Colitis. 2012;6:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Remes O, Brayne C, van der Linde R, et al. A systematic review of reviews on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in adult populations. Brain Behav. 2016;6:e00497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weissman MM, Bland R, Joyce PR, et al. Sex differences in rates of depression: cross-national perspectives. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bray RM, Camlin CS, Fairbank JA, et al. The effects of stress on job functioning of military men and women. Armed Forces Soc. 2001;27:397–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zeiss AM, Karlin BE. Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]