Abstract

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a rare congenital disorder with an incidence of 1 in 100,000. It is characterized by a triad of capillary malformations (hemangiomas) or port-wine stains, venous varicosities, and bony- or soft-tissue hypertrophy. The capillary malformation is usually confined to a single extremity, usually a lower limb. The disease can lead to various morbidities, such as bleeding, deep vein thrombosis, venous ulcers, and embolic complications. We report a case of an 11-year-old girl who presented with the three classical symptoms of KTS, with port-wine stains in the left leg, an enlarged and elongated left leg, and soft-tissue hypertrophy and multiple venous varicosities in the left tibia. A subcutaneous hemangioma along with intramuscular hemangiomas in the leg muscles was noted with increased adipose tissue. The rare finding of an intraneural hemangioma of the distal posterior tibial nerve was also diagnosed. Ultrasound of the lower limb was the main tool in making the diagnosis of KTS. X-Ray and MRI were ancillary imaging modalities. This article describes the case study of the child and the findings of a detailed ultrasound examination.

Keywords: Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, Angio-osteo-hypertrophy, Adipose tissue, Haemangiomas, Musculoskeletal ultrasound, Color Doppler, Intraneural hemangioma, Intramuscular hemangioma, Hemihypertrophy, Varicose veins

Introduction

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS), a rare congenital disorder with an incidence of 1 in 100,000 [1], is an angio-osteo-hypertrophic syndrome characterized by the classical triad of cutaneous capillary hemangiomas or port-wine stains, bony- or soft-tissue hypertrophy of an extremity (localized gigantism), and varicose veins or venous malformations.

The diagnosis of KTS is usually made when any two of the three features are present. Capillary malformations may be absent in the atypical form. The malformation is usually limited to a single extremity, usually the lower limb. When associated with AV fistulas, it is known as Parkes–Weber syndrome.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound (US) and Doppler are essential for the diagnosis of rare diseases such as KTS and its various symptoms in the vascular and musculoskeletal system.

Case report

An 11-year-old girl clinically presented with elongation and gradually increasing girth of the left leg for the past 5 years (Fig. 1). She has multiple focal small cutaneous capillary hemangiomas/nevi of varying sizes in the anterior and medial aspects of the lower thigh and in the anterior aspect of the knee and mid leg. The lesions are reddish-purplish in color. According to her parents, the skin lesions were hardly present at birth, and they appeared when the child was around 4 years old, gradually increasing in size and number for the past 7 years. The child has no sensory or motor weakness. Gait is normal, but she complains of a dull ache at the back of her knee joint. No other history of bleeding was given.

Fig. 1.

This image shows the hypertrophy of the left limb with an increase in its length and girth. A few scattered port-wine stains or capillary hemangiomas were noted

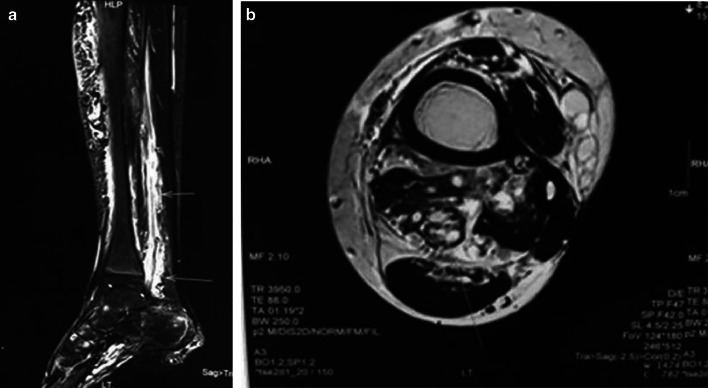

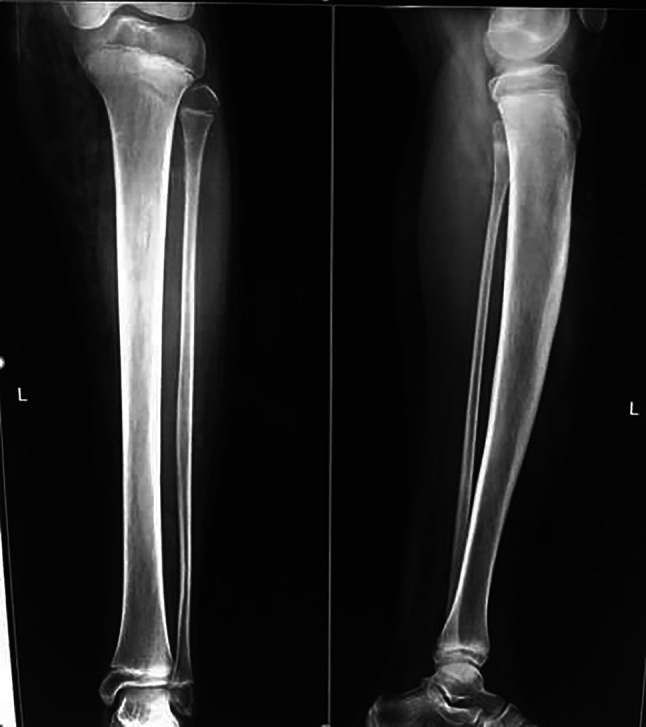

The preliminary X-ray of the left leg reveals a mild thickening of the girth of the tibia.

The architecture of the cortex and medulla appeared normal. No lytic or sclerotic lesion was seen. Elongation of the tibia was noted (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

X-Ray reveals a thickening of the tibia with no architectural distortion. There was an increase in soft-tissue thickness mainly in the anterior and medial aspects of the leg. No calcification was noted

US of the subcutaneous tissue and skin revealed multiple—some ill-defined and others well-defined—hypoechoic masses of heterogeneous echotexture with multiple anechoic spaces within them. These masses were in the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior mid thigh, the medial lower thigh, the anterior aspect of the mid tibia, and the lateral aspect of the lower leg.

The anechoic and hypoechoic spaces were surrounded by hyperechoic tissue suggestive of adipose tissue. Small focal calcification was noted in the lower thigh lesion suggestive of a phlebolith. Color Doppler revealed no detectable or weak venous flow in the lesions.

Capillary hemangiomas in the skin were away from the site of the subcutaneous hemangiomas. A mild hyperechoic thickening of the skin was noted at the site with no detectable flow (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Subcutaneous hemangioma in the thigh, consisting of an ill-defined hypoechoic mass in the subcutaneous tissue with anechoic spaces showing venous flow on color Doppler. The lesion is surrounded by hyperechoic fatty tissue

Multiple dilated linear and round tortuous vascular venous channels were also noted in the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior and medial aspects of the leg with an associated hyperechoic subcutaneous fat thickening.

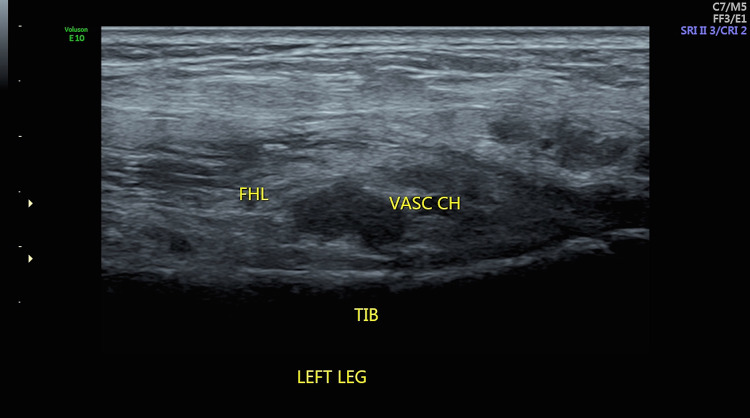

The plane in the leg, between the soleus muscle and the tibialis posterior and the flexor hallucis longus muscles, shows an increased amount of hyperechoic fatty tissue with numerous anechoic venous channels within them. Color Doppler showed a weak venous flow in some of them. The increase in adipose tissue is seen to extend inferiorly to Kager’s fat pad deep to the Achilles tendon with multiple dilated venous channels within it (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kager’s fat pad shows an increased fat component with dilated venous channels within it. The underlying FHL is also heterogeneous with an ill-defined mass

The posterior tibial artery was normal.

The tarsal tunnel in the medial ankle also shows increased hyperechoic adipose tissue with a smooth bulge of the flexor retinaculum. The posterior tibial vessels and the posterior tibial nerve embedded in it were normal.

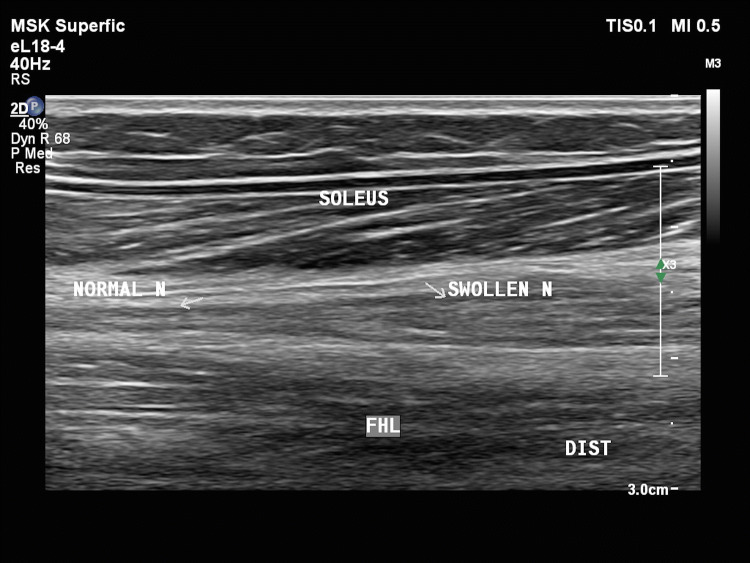

With regard to nerves, an assessment of the posterior knee and leg was made. This revealed a long segment of a swollen posterior tibial nerve in the widened intermuscular fat plane deep to the soleus muscle along the posterior tibial vessels and dilated venous channels (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Intraneural hemangioma of the posterior tibial nerve. The posterior tibial nerve is swollen and hypoechoic. Anechoic tubular channels are noted between the nerve fascicles along their long axis. The nerve fascicles maintain continuity

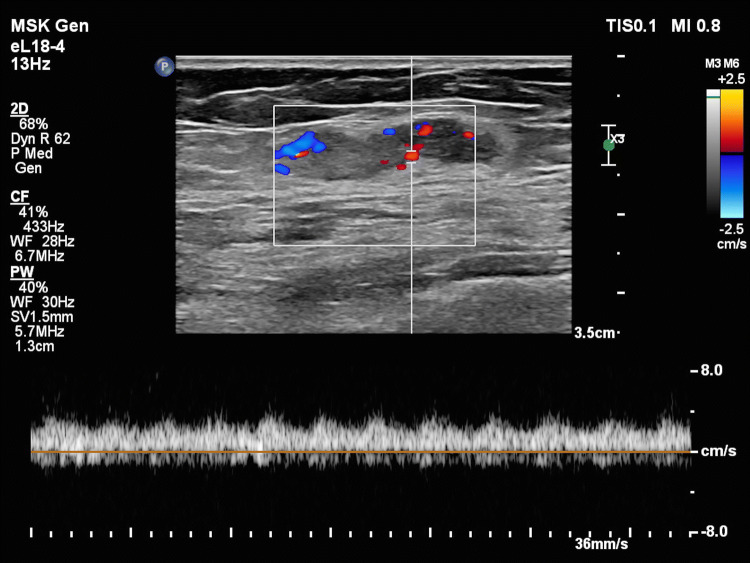

The part of the nerve involved (approximately 10 cm long with a cross-sectional area of 0.4 cm2)—whose fascicles, however, were continuous—was mainly hypoechoic with multiple anechoic tubular structures within it along the long axis of the nerve. A few of these tubular channels showed flow on color and power Doppler (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Intraneural hemangioma of the posterior tibial nerve. Doppler reveals venous flow in anechoic tubular channels

The posterior tibial nerve was traced proximally to the popliteal fossa and the sciatic nerve bifurcation and distally up to the tarsal tunnel. The nerve showed gradual tapering both proximally and distally and had normal filamentous echotexture and a normal diameter from mid leg superiorly and from the supramalleolar region inferiorly.

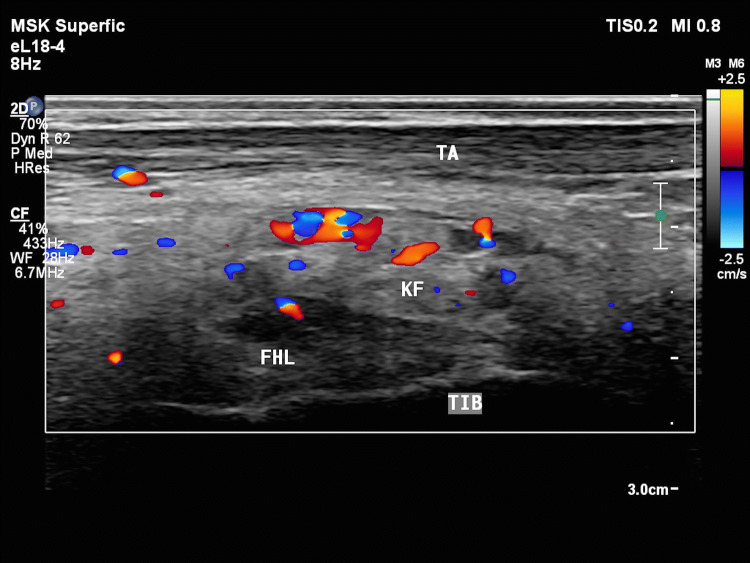

As for the muscles, a few anechoic dilated venous channels, which showed a weak flow on color Doppler, were noted in the tibialis anterior muscle in the mid leg. Mild hyperechoic adipose tissue is seen to surround these vessels. The flexor hallucis longus muscle was mildly enlarged. An ill-defined mass lesion with heterogeneous echotexture, adipose tissue, and multiple tubular internal hypoechoic areas with venous flow was noted in the bulk of the muscle in the lower leg (Fig. 7). These features suggested intramuscular hemangiomas of the tibialis anterior and flexor hallucis longus muscles.

Fig. 7.

Intramuscular hemangioma in the flexor hallucis longus muscle. Enlarged FHL with an ill-defined mass showing heterogeneous echotexture. Multiple tubular anechoic structures with weak venous flow on color Doppler (see Fig. 4). Adipose tissue is also noted at places. The lesion blends imperceptibly with Kager’s fat pad

A Doppler study of the superficial venous system revealed a dilated vein in the subcutaneous tissue of the lower third of the leg lateral to the lateral malleolus. It is narrow over the lateral malleolus and is seen to become gradually dilated as it ascends superiorly. The vein is seen to go anteromedially in the mid leg over the tibia. It is seen in the anterior medial aspect in the upper leg and in the medial aspect of the knee and was noted to be in continuation with the great saphenous vein (GSV), which was traced distally from the saphenofemoral junction. The GSV showed a normal course in the thigh with gradual dilatation distally.

The saphenofemoral junction was competent. A few dilated perforators were noted from the GSV in the lower thigh and the upper medial leg. This entire subcutaneous venous channel was patent with normal flow and response to a Valsalva maneuver and distal compression. The short saphenous vein did not show any flow. Its diameter was narrow with an echogenic rim. Multiple superficial varicosities were noted in the subcutaneous tissues of the anterior and medial aspects of the leg.

The deep venous system was normal with a normal diameter and flow. No thrombosis was noted.

An MRI study of the left leg in 3D was carried out mainly for further evaluation of the intraneural hemangioma and the bone marrow.

The left tibia was thickened with bone edema. A large tortuous vascular channel was noted in the lateral aspect of the distal leg going anteromedial proximally. An intraneural hemangioma of the distal posterior tibial nerve, as well as intramuscular hemangiomas of the flexor hallucis longus, soleus, tibialis anterior, and peroneal muscles, was noted.

Subcutaneous fat, as well as the deep fascia, was thickened with a linear vascular channel with aneurysmal dilatations in the subcutaneous fat. Prominent vascular channels were noted beneath the deep fascia (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Thickening of the tibialis posterior nerve was noted with intraneural T2 hyperintense foci. The thickened nerve appears isointense on the Tl-weighted image, suggestive of an intraneural hemangioma. The lesion was seen to extend from the mid third of the leg to above the tarsal tunnel. The thickened nerve measured up to 2 cm

Discussion and conclusion

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a rare complex congenital anomaly with an incidence of 1 in 100,000. It is considered an angio-osteo-hypertrophic syndrome [2, 3], and it was first described by two French doctors, Klippel and Trenaunay, in 1900 [2].

The etiology of KTS is still uncertain. It is sporadic and occurs worldwide. There is no sex predilection or family inheritance. It can be caused by somatic mutations in the PIK3CA gene, which lead to increased cell proliferation resulting in abnormal growth of bones, soft tissue, and blood vessels [1, 3]. Recent theories suggest a mesodermal abnormality during fetal growth [2, 4].

KTS classically comprises a triad of cutaneous capillary hemangiomas or port-wine stains, bony- or soft-tissue hypertrophy of an extremity (localized gigantism), and varicose veins or venous malformations of unusual distribution. Diagnosis, potentially made prenatally [2] or at birth [3], is usually made when any two of the three features are present, but the capillary malformations may be absent in the atypical form. KTS has no significant arteriovenous shunting, the absence of which is an important differentiating feature with Parkes–Weber syndrome.

Port-wine stains or capillary malformations in KTS are of the nevus flammeus type and are limited to the skin. They often have a patchy distribution and are reddish-purplish in color. Typically, they involve the enlarged limb, as was seen in our case. But they can be seen in any part of the body. If they are large enough, the cutaneous lesions may sequester platelets, leading to a consumptive coagulopathy called Kasabach–Merritt syndrome [5].

Bony- or soft-tissue hypertrophy of an extremity is the most variable of the three classic features of KTS. Enlargement of the extremity can be either bone elongation and overgrowth, leading to limb length discrepancy and circumferential soft-tissue hypertrophy, or increased vascular tissue thickness, leading to increased limb girth, or both [3, 6]. All these features were seen in our case.

Tissue overgrowth is secondary to impaired venous return [6]. Chronic venous hypertension during childhood has been suggested as a cause of limb gigantism, and this gigantism is disproportionally large distally [7].

Subcutaneous fat hypertrophy may be seen [8]. Adipose tissue is most prominent along the circumference of the vascular complex in soft-tissue hemangiomas. This fatty tissue may reflect muscle atrophy secondary to chronic vascular insufficiency, caused by the steal phenomenon. In some patients, the fat overgrowth is so prominent that the lesions can be mistaken for lipomas [9]. In our patient, there was an increase in adipose tissue in the subcutaneous tissue of the leg as well as in the deep intermuscular fat planes, Kager’s fat pad, and the tarsal tunnel, especially in relation to hemangiomas and venous malformations.

Varicosities or venous malformations are present in 72% of KTS patients [10], and these are congenital. Varicosities are extensive, atypically very large, and begin to manifest in early childhood [7]. They can be present at birth or arise shortly thereafter. They may be slowly progressive or may remain static [6]. They involve extensive areas of the affected extremity without a saphenous distribution. These venous abnormalities can occur in the superficial, deep, and perforating systems [10].

Abnormal venous drainage is frequently caused by persistent embryonic veins, agenesis, hypoplasia, valvular incompetence, or aneurysms of deep veins. Persistence of embryonic veins can be seen, in which the lateral marginal vein (vein of Servelle) is involved in 60–80% of patients [1, 7]. In patients with deep venous aplasia, it may act as a collateral channel [7], but deep venous aplasia is less common than previously thought [11].

In addition, lymphatic malformations may be an association, but they do not necessarily constitute the syndrome [7]. Varicose veins can cause comorbidities, such as deep vein thrombosis, skin ulcers, cellulitis, and embolic complications, as well as bleeding from abnormal vessels in the intestine and genitourinary systems [1].

In our case, US revealed anomalous venous channels and varicosities mainly involving the superficial venous system. The deep venous system was patent and mildly dilated.

US with color Doppler has a role in identifying the abnormal venous system and varicosities as well as the associated hemangiomas. The flow characteristics of venous malformations are best demonstrated by US. US is superior to the more established venographic techniques in the investigations of patients with KTS [11].

In plain radiographs, phleboliths in a young patient are usually diagnostic for venous malformations [5].

Currently, it is said that MRI is the method of choice for the identification of soft-tissue and intraneural hemangiomas [9, 12], but with the advent of high-resolution transducers, muscle-skeletal US has become a very reliable diagnostic tool for evaluation of the above. US can help to evaluate subcutaneous tissues, muscles, nerves, and intra- and intermuscular fat. In our case, it has helped to diagnose not only the venous varicosities and malformations but also the soft-tissue and nerve hemangiomas, as well the increase in adipose tissue.

In port-wine stains, US is usually unable to display such superficial abnormalities limited to the dermis. In some instances, however, an increased thickness of the subcutaneous tissue and some prominent veins may be demonstrated [13]. In our case, the area of port-wine stains revealed a thickening of the dermis.

Subcutaneous hemangiomas may be hypoechoic or hyperechoic relative to the surrounding tissue and may have a homogenous or a complex appearance. Prominent vascular channels, phleboliths, and fat can be seen. In our case, subcutaneous hemangiomas were seen as ill-defined or well-defined hypoechoic heterogeneous mass lesions with multiple anechoic spaces within them. Color Doppler showed absent or weak flow within these spaces. The lesions were surrounded by hyperechoic reactive fatty tissue, and a phlebolith was detected in one lesion in the thigh.

In general, vascular malformation can be distinguished from hemangiomas owing to the absence of solid tissue [13]. Arteriovenous malformations can be differentiated from hemangiomas as they show high vascularity and a higher mean peak systolic velocity on Doppler US [13, 14].

Intramuscular hemangiomas can be well detected by US, which is also effective in the follow-up [12]. US demonstrates a complex, ill-defined mass within the affected muscle, characterized by a mixture of hypoechoic (blood-filled cavities) and hyperechoic (reactive fat overgrowth) components. The heterogeneous appearance of intramuscular hemangiomas depends on the variety of tissue found. Prominent vascular channels can be identified on grayscale imaging. During prolonged observation, very slow blood motion in the hypoechoic cavities of the mass can be recognized as a “swarming mass.” One-to-one correlation between US and MR images shows good correspondence [13]. Doppler can identify prominent vascular channels, abnormal flow patterns, or may not be useful if the flow is too slow [12, 13, 15]

Sometimes, the boundaries of the lesion are undefined, especially in large masses infiltrating more than one muscle or blending imperceptibly with the intermuscular fatty planes [12, 13].

In our case, US detected two of the four intramuscular hemangiomas diagnosed on MRI. The hemangioma in the flexor hallucis longus muscle was seen as an ill-defined mass lesion with heterogeneous echotexture, adipose tissue, and multiple tubular anechoic areas with venous flow on color Doppler. The tibialis anterior muscle just showed dilated venous channels with weak flow on color Doppler, and hyperechoic adipose tissue was seen surrounding these vessels.

Intraneural hemangiomas are very rare, benign, mesodermal tumors [16, 17]. As an isolated finding, these rare lesions may involve various peripheral nerves, most commonly the median nerve. Tibial nerve hemangiomas, on the other hand, are extremely rare even as isolated findings [16]. There has been no reported case of intraneural hemangiomas associated with KTS.

Currently, the standard for evaluating soft-tissue and intraneural hemangiomas is MRI [9]. US is useful for detection and assessing size and location and provides real-time dynamic information on the tumor’s vascularity and relation to surrounding soft-tissue structures [16, 18]. On US, intraneural hemangiomas may have a heterogeneous appearance with a variable echogenicity, ranging from hypoechoic to hyperechoic relative to the surrounding soft tissue. They may be well defined with posterior acoustic enhancement, or they may infiltrate surrounding soft tissues [17]. US may reveal a markedly swollen nerve containing large intraneural fluid-filled places, separating the fascicle. Typically, these anechoic spaces are oriented along the long axis of the nerve. Some may show varied echogenicity with multiple cystic spaces [18].

Color and power Doppler show slow-flowing blood within them with venous waveforms [13]. However, Doppler US may detect only sparse flow in the slow-flow involuted hemangiomas, in which case a compression test may show increased blood flow inside the lesion. Lack of blood flow may be related to thrombosis or hemorrhage within the lesion [17].

Surgical neurolysis of nerve hemangiomas is not recommended as intraneural vessels are part of the “vasa vasorum” system and because of the intermingled distribution of vessels with fascicles [13].

In our case, intraneural hemangiomas of the distal posterior tibial nerve were reliably diagnosed by muscle-skeletal US, with a clear demonstration of the long, thickened segment of the hypoechoic nerve and the anechoic venous channels within it along the long axis; this segment showed flow on power Doppler. Continuity of the nerve fascicles was seen. The findings were comparable to the MRI findings.

In conclusion, US with color Doppler has a role in identifying the abnormal venous system and varicosities as well as the associated hemangiomas. US is superior to the more established venographic techniques in the investigations of patients with KTS. In addition, US can help to evaluate subcutaneous tissues, muscles, nerves, and intra- and intermuscular fat.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they do not have conflict of interest to disclose. The estatement have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and its late amendments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Alwalid O, Makamure J, Cheng Q, et al. Radiological aspect of Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome: a case series with review of literature. Curr Med Sci. 2018;38:925–931. doi: 10.1007/s11596-018-1964-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cakiroglu Y, Doğer E, Yildirim Kopuk S, Dogan Y, Caliskan E, Yucesoy G. Sonographic identification of Klippel–Trenaunay–Weber syndrome. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:595476. doi: 10.1155/2013/595476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob AG, Driscoll DJ, Shaughnessy WJ, et al. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: spectrum and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:28–36. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63615-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oluwafemi AJ, Omokafe LR, Maduka Ogechi CD, Ganiyu A, Bako IJ, Oluleke IP, Ifeoma IC. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: a rare case presenting in a 5-years-old girl. West Afr J Radiol. 2016;23:136–139. doi: 10.4103/1115-1474.164870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kharat AT, Bhargava R, Bakshi V, Goyal A. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: a case report with radiological review. Med J DY Patil Univ. 2016;9:522–526. doi: 10.4103/0975-2870.186069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gulati YS, Pathak K, Naware SS, Negi RS. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Med J Armed Forces India. 2004;60:73–74. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdul-Rahman NR, Mohammad KF, Ibrahim S. Gigantism of the lower limb in Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome: anatomy of the lateral marginal vein. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:e223–e225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy OJ, Gafoor JA, Rajanikanth M, Prasad PO. Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome with review of literature. J NTR Univ Health Sci. 2015;4:120–123. doi: 10.4103/2277-8632.158592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen KI, Stacy GS, Montag A. Soft-tissue cavernous hemangioma. Radiographics. 2004;24:849–854. doi: 10.1148/rg.243035165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung SC, Lee W, Chung JW, et al. Unusual causes of varicose veins in the lower extremities: CT venographic and Doppler US findings. Radiographics. 2009;29:525–536. doi: 10.1148/rg.292085154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howlett DC, Roebuck DJ, Frazer CK, Ayers B. The use of ultrasound in the venous assessment of lower limb Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome. Eur J Radiol. 1994;18:224–226. doi: 10.1016/0720-048X(94)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown RA, Crichton K, Malouf GM. Intramuscular haemangioma of the thigh in a basketball player. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:346–348. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.004671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bianchi S, Martinoli C. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toprak H, Kilic E, Serter A, Kocakoc E, Ozgocmen S. Ultrasound and Doppler US in evaluation of superficial soft-tissue lesions. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2014;4:12. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.127965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wierzbicki JM, Henderson JH, Scarborough MT, et al. Intramuscular hemangiomas. Sports Health. 2013;5:448–454. doi: 10.1177/1941738112470910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwong S, Seeger LL, Motamedi K, Nelson SD, Golshani B. Intraneural hemangioma: case report of a rare tibial nerve lesion. Cureus. 2018;10:e3784. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song HB, Lee YH, Kang UR, Lee SM, Chae SB. Ultrasound and MRI finding of intraneural capillary hemangioma of the median nerve mimicking traumatic neuroma: a case report. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2018;78:115–119. doi: 10.3348/jksr.2018.78.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy YM, Meena AK, Uppin MS, Vadapalli R, Challa S. Intraneural capillary hemangioma: a rare cause of proximal median neuropathy. Neurol India. 2013;61:660–662. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.125280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]