Abstract

Soft-tissue palpable lesions are common in clinical practice, and ultrasound (US) represents the first imaging option in the evaluation of a patient with a soft-tissue swelling. A full and systematic US assessment is necessary, however. This includes grayscale, color- and power-Doppler, spectral-Doppler, and possibly elastography facilities, as well as a trained operator. Several lesions showing characteristic US features can be diagnosed confidently, without any further work-up, and the high spatial resolution of ultrasound in the superficial layers can be a powerful tool to discriminate their etiologies. Second-level options, to be reserved for indeterminate cases or those suspected malignant at initial ultrasound, include magnetic resonance imaging, percutaneous fine-needle aspiration or biopsy, and surgical-excision biopsy. In this article, we discuss the proper US approach for addressing superficial soft-tissue lesions.

Keywords: Soft-tissue ultrasound, Color-Doppler ultrasound, Dermatology ultrasound, Skin tumors, Soft tissues, Soft-tissue sarcoma

Introduction

Superficial soft-tissue masses represent a common occurrence in clinical practice; most are benign, with the benignity to malignancy ratio over 100:1 [1]. Early, accurate diagnosis with subsequent appropriate treatment is crucial for the clinical outcome of soft-tissue sarcomas [1, 2]. The challenge of managing patients with a soft-tissue mass is to avoid extensive studies and unnecessary surgery in the large number of patients with benign abnormalities, while avoiding delayed diagnosis in the small number of patients with malignancy [3]. The patient presenting with a superficial palpable lesion may have a vast number of underlying abnormalities (Table 1) [4–11]. In 1 MRI study of 136 patients with “superficial soft-tissue tumors,” [12] the abnormalities detected most frequently were lipoma (11 cases), spindle cell sarcoma (11 cases), myxofibrosarcoma (9 cases), liposarcoma (8 cases), lymphoma (8 cases), fat necrosis (8 cases), hemangioma (7 cases), fibromatosis (5 cases), unclassified sarcoma (5 cases), and synovial sarcoma (5 cases). US series include a significantly higher rate of benign lesions [3, 5, 8, 11].

Table 1.

Main soft-tissue masses that can be encountered in clinical practice

| Normal or abnormal lymph node |

| Hematoma (spontaneous or traumatic) |

| Muscle hernias |

| Foreign body |

| Retained fillers after esthetic procedures |

| Granulomas |

| Pilomatrixoma |

| Sinuses and fistulas (congenital or acquired) |

| Infections (cellulitis, abscess, phlegmon) |

| Hydatid disease |

| Tuberculosis |

| Parasitic infections (Sarcoptes scabei, Demodex species, Tunga penetrans, myiasis-causing fly larvae, Leishmania, round worms, tapeworms, flukes, etc.) |

| Surgical complications (seroma, lymphocele, gossypiboma, etc.) |

| Granuloma annulare |

| Myositis ossificans circumscripta |

| Gout nodules |

| Fat necrosis (steatonecrosis), including necrosis after lipofilling procedures |

| Pseudocysts (acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, etc.) |

| Cysts (epidermal inclusion cyst, dermoid cysts, trichilemmal cysts, etc.) |

| Myxoma |

| Synovial abnormalities (synovial cyst [ganglia], pigmentous villonodular synovitis, synovial osteochondromatosis) |

| Tendon tumors (fibroma of tendon sheath, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath, intratendinous ganglia, etc.) |

| Fibroplastic/myofibroplastic tumors and pseudotumors (nodular fasciitis, fibroma nodular fasciitis, elastofibroma, superficial fibromatosis [palmar or plantar], deep fibromatoses [desmoids, etc.]) |

| Vascular lesions (pseudoaneurysm, thrombosed arteries or veins, hemangioma, lymphangioma, arterio-venous malformation, glomic tumor, etc.) |

| Angioleiomyoma |

| Adipocytic tumors (lipoma, angiolipoma, lipoblastoma [infantile lipoma], hibernoma, etc.) |

| Lymphoma (primary and secondary) |

| Neurogenic lesions (peripheral nerve sheath tumors, neuromas, amputation neuromas) |

| Sarcomas (liposarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans) |

| Metastasis (cutaneous melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, myeloma, other primary tumors) |

| Iatrogenic tumor seeding |

US is commonly regarded as the imaging modality of choice in the assessment of palpable soft-tissue abnormalities [3, 13]. According to the appropriateness criteria of the American College of Radiology, US is “usually appropriate” to evaluate superficial or palpable soft-tissue masses, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is “usually appropriate” in case of nondiagnostic initial US evaluation [14]. In the superficial layers, US presents a much higher spatial resolution than do computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for discriminating differences in the tissues. Thus, US can detect submillimeter alterations, while CT and MRI can only detect and diagnose an entity confidently in lesions measuring ≥ 5 mm. Examples of these limitations are nail tumors or metastasis of melanoma that measures 3 mm, which could be false negatives on MRI or PET-CT [15–19].

In the case of soft-tissue lesions, the goals of US imaging are to confirm the actual presence of a focal lesion (i.e., rule out any mimicker), establish the precise features of the lesion (location, size, structure, etc.), differentiate solid from cystic and malignant from benign lesions, provide a definitive (histology-like) diagnosis (if possible), plan and guide the cytology/histology sampling (when needed), help establish the best management, identify the involvement of any critical adjacent structure or the presence of any anatomical variation of interest for the surgical exposure and excision, and follow-up the area after treatment (if needed) [3, 13, 14, 20, 21].

Systematic approach

There are some preliminary key questions the US operator must ask the patient when approaching a new soft-tissue lesion [3]. Time from identification of the swelling is critical and should be categorized in terms of a few days, a few weeks, a few months, more than 1 year, or several years. In some cases, the patient seeks medical attention when he/she discovers the lesion, although it may have been presented much longer. In other cases, the patient has been aware of the lesion for months or years before but, due to its slow growth and the absence of pain, it has been not a concern. In the latter case, it is our experience that patients are frequently vague in indicating the time intervening from the lesion growth, usually underrating it. Congenital abnormalities represent a special subset. It is also essential to know whether the lesion has undergone any change in its diameters since the lesion was first noted, although most if not all subjects answer affirmatively. Then, it is important to ask the patient whether the lesion is painful. The degree of pain is important, as well as whether the pain is spontaneous or only elicited by hand pressure. As a more objective confirmation, the probe pressure above the lesion could confirm precisely whether the lesion corresponds to the site of the pain. As a general rule, painless lesions will be regarded with more suspicion of malignancy than painful ones. Finally, a patient’s recent and long-term history, such as the presence of any previous or concomitant major systemic disease, including cancer, diabetes, and immunodepression, should be investigated. Also valuable for framing are recent events, such as a history of surgical or non-surgical procedures, injury, drug consumption, or travel in tropical countries. Any change on the overlying skin should be noted. Additionally, the whole area where the lesion is located must be carefully inspected, looking for scars, wounds, pimples, etc. [3].

Consider also the patient’s age. For example, pilomatricomas are rarely encountered in adults but are a relatively common occurrence in childhood. Epidermal cysts most commonly affect young- and middle-aged adults. Melanoma metastases are quite rare in infancy, while patients with Merkel cell carcinoma metastasis are usually older than 70 years. For purposes of analysis, it is useful to consider two patient age groups: adults and children/adolescents [10]. Additionally, some lesions are found frequently in some body areas and rarely in others. Epidermal cysts commonly present on the scalp, face, neck, trunk, and extremities [22]. Muscle hernias are quite typical on the legs [23]. Ganglions arise from tendons or joints. Neural fibrolipoma is typically seen at level of the median nerve [5]. More than 40% of epithelioid sarcomas occur in the hand and wrist [10].

B-mode scanning

Only after the preliminary clinical assessment will US imaging be carried out. Owing to the high resolution of current transducers and to Doppler and elastography capabilities, US is the first-choice imaging modality in the assessment of superficial soft-tissue lesions. Hockey-stick-shaped probes represent a useful tool, particularly for studying the face, fingers, and nails, as well as to scan children [11]. The highest possible transmission frequency that provides adequate deep visualization will be chosen [3]. One or two variable-frequency transducers, covering a frequency between 7.5 and 22 MHz, must be available, according to the depth of the lesion [18, 24] (Figs. 1, 2). The same applies to the time-gain compensation curve regulation. For larger patients or in some anatomical areas (proximal thigh, buttocks), low-frequency transducers may be needed [5, 25].

Fig. 1.

Epidermal cyst. When imaged at 13 MHz, the lesion appears as a non-specific, subcutaneous, hypoechoic nodule without Doppler signals (a). When using a 22 MHz probe, the cystic duct becomes evident, allowing a definitive diagnosis (b)

Fig. 2.

Pericicatricial seroma in a patient with recent melanoma exeresis. If scanned at 13 MHz, the lesion appears as a small, avascular, non-specific nodule (a). When imaged at 22 MHz, the lesion is clearly anechoic (b)

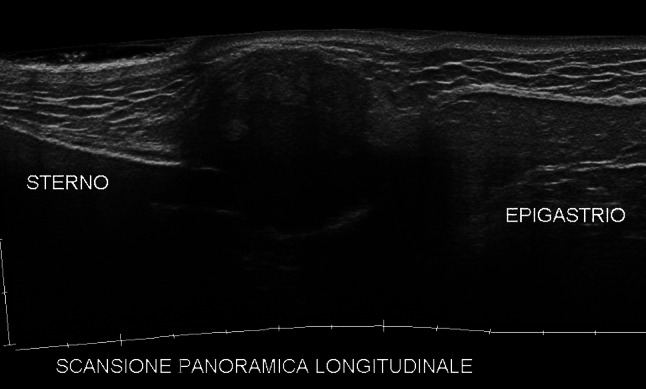

The gain should be increased to amplify the echoes, but not excessively so as to avoid creating artifacts. For very superficial lesions, the use of a large gel heap or a gel-pad spacer can be helpful [26]. The field of view (FOV) will be adjusted according to the appropriate depth, and the focal zone will be placed at level of the abnormality [20]. Trapezoid scans, widening the rectangular FOV at its deeper aspect, are useful to display large, deep lesions or to measure the distance between multiple lesions [27]. Real-time, extended-FOV scans have also proven useful to better define the spatial relationship between multiple lesions and between the abnormalities and anatomic landmarks (vessels, bony promontories, etc.). Additionally, extended-FOV images improve the display and measurement of very large abnormalities [5, 25, 28] (Fig. 3). The optimal patient positioning should be found, allowing the lesion to bulge clearly and the operator’s hand to be stable [29]. Dynamic assessment during passive movements, active movements, or Valsalva maneuver can be useful for both diagnosis and assessment of the relationship of the lesional area with the surrounding structures [20, 23, 25, 30]. The lesion is scanned on multiple axes, and comparative scans of the contralateral side can be helpful, particularly when the initial US scanning fails to identify a focal abnormality or when it is necessary to detect subclinical contralateral involvement [5].

Fig. 3.

Sagittal extended field-of-view scan of the chest. A xiphoid appendix plasmacytoma mass—hypoechoic, ill-defined, and heterogeneous—is optimally displayed at the tip of the sternum

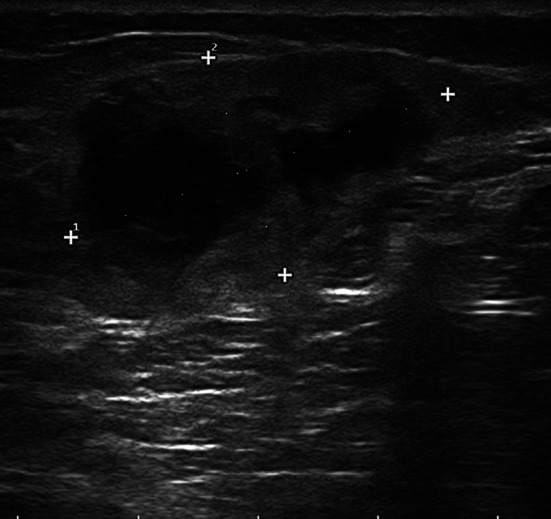

Several features must be considered when writing the report [5, 20]. The number of lesions must be described, whether solitary or multiple. The location of the lesion will be established, considering whether it involves the epidermis, dermis, superficial hypodermis, deep hypodermis, fascia, muscular layer, or a combination of the above. Two orthogonal diameters will be traced, and the measures will be recorded in millimeters (Fig. 4). Definition of the shape, such as, round, oval, polilobulated, or irregular, is releveant. As with thyroid and breast nodules, the spatial orientation will be observed and separated into sub-orientations parallel to the skin (i.e., to the probe) or perpendicular (i.e., vertical or depth axis). The internal echotexture of the lesion will be analyzed: whether cystic, solid, mixed with cystic prevalence, mixed with solid prevalence, pseudosolid (solid-looking, fluid-containing lesions), or pseudocystic (cystic-looking solid lesions). Melanoma lesions and lymphoma lesions can be quite echo-free, mimicking a cystic lesion [31]. Complex fluid masses are usually, but not always, benign; for example, a hematoma may mimic a sarcoma and vice versa [25, 32]. The strength of the echoes in comparison with the surrounding plane will be evaluated: whether hyperechoic, isoechoic, hypoechoic, or anechoic, and whether homogeneous or heterogeneous. Special contents, such as calcifications (marginal, radial, or spot-like), septations (fine or thick), or hair (linear echogenic reflections) will be noted, as well as the presence of any tail (one or two poles), connection or duct, and the presence of any capsule (intact or ruptured). A tail may indicate a neural origin or, sometimes, the growth of a melanoma metastasis along a tumor-filled lymphatic vessel [33]. A hypoechoic tract reaching the epidermis is a common finding in epidermal cysts, although the corresponding “punctum” will be visible clinically only in a minority of the cases. In addition, fistulized abscesses show a tract. Synovial cysts usually show joint connections [5]. Margins can be sharp and well defined or blurred and ill defined. The spreading pattern within the area of growth can be expansile, displacing the adjacent structures (tendons, muscles, fasciae, vessels, nerves, etc.), or infiltrating, with penetration and encasement of the surrounding structures. Bony scalloping or cortical irregularity must be noted. The acoustic behavior of the tissue deeper than the lesion must be evaluated, considering whether it increases through transmission (acoustic enhancement) or increases attenuation (acoustic shadowing). The appearance of perilesional tissues must be considered, looking for any haziness, halo, or edema. The lesion may or may not be deformable under the probe pressure, mobile, painful, or pulsatile [20].

Fig. 4.

Sarcoma of the tight. Proper measurement of the mass requires tracing the largest diameter and the largest diameter perpendicular to the former (34 × 19 mm)

Experience with computer-assisted diagnosis (CAD) of soft-tissue masses is still preliminary. Chiou and coauthors extracted from the US images five features: area, boundary transition ratio, circularity, high intensity spots, and uniformity. The CAD system achieved 88% sensitivity and 87.5% specificity in differentiating benign from malignant masses [34].

Color-Doppler assessment

Doppler assessment of the presence and distribution of flows around and within the lesion is mandatory and should never be neglected in an ultrasound study of a superficial abnormality. The presence of even minimal flow signals, providing that they are not artifacts, indicates confidently that the lesions are solid. The contrary is not always true, since flows may be too slow to be detectable by Doppler techniques.

To properly analyze the flow signals, the scanner must be set to detect slow flows. This means a high Doppler transmission frequency, a low pulse repetition frequency, a low or null wall filter, a high color gain (just below the noise threshold), and a minimized color box [3, 13, 20, 25, 29, 35]. In many scanners, the power-Doppler mode is more sensitive than the color-Doppler one and consequently should be favored by the operator [20].

Additionally, it is always essential to avoid excessive pressure with the probe over the lesion [20, 25]. If the lesion is located in the neck or thoracoabdominal region of the patient, he or she should hold his or her breath for a while to minimize artifacts [29]. Additionally, it is always essential to avoid excessive pressure with the probe over the lesion [20, 25].

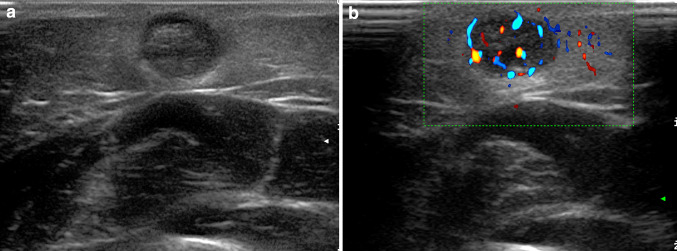

The following aspects of lesion vascularization must be evaluated and indicated in the report: presence of perilesional flow signals, presence of intralesional flow signals, distribution of intralesional flow signals (peripheral vs. central, symmetric vs. asymmetric), appearance of intralesional vessels (regular vs. heterogeneous, pulsatile or not), and presence and number of vascular poles, feeding vessels, or stalks (Figs. 5, 6) [35].

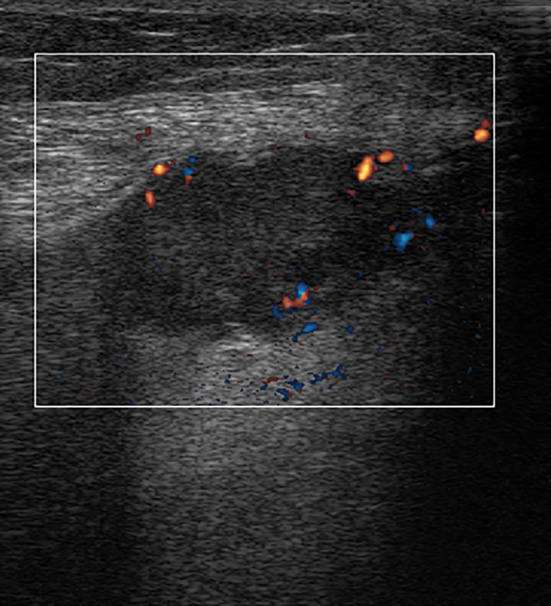

Fig. 5.

Locally recurring leg sarcoma. Directional power-Doppler scan. Heterogeneous, hypoechoic nodule with peripheral vascularization

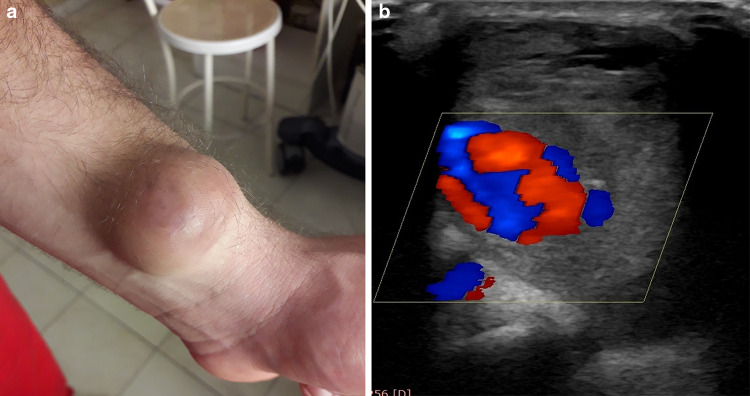

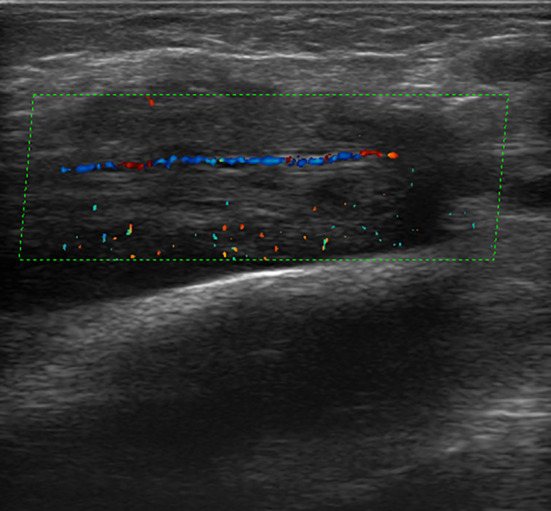

Fig. 6.

Young butcher with wrist swelling 4 months after a knife wound. Patient photograph (a). Color-Doppler scan depicts a radial artery pseudoaneurysm (b)

New tools for microvasculature display have recently been developed by many manufacturers [36]. These applications tend to be more sensitive for detecting slow flow in comparison with color- or power-Doppler and also use a higher frame rate. If available, their use is desirable.

Spectral-Doppler analysis

Sampling of the Doppler spectrum is not performed routinely. In some lesions, however, detection of the spectral curve can be critical, not only for differential diagnosis, but also for categorization and management. This includes mainly vascular abnormalities, such as hemangiomas or vascular malformations and sarcomas. The maximum systolic velocity and the resistive index must be recorded, with the latter providing an indirect estimation of the intralesional microcirculation. Doppler spectrum analysis allows to establish the kind of flow (arterial, venous, or both) and categorize the arterial flows as high or low speed and as high or low resistance.

Elastography assessment

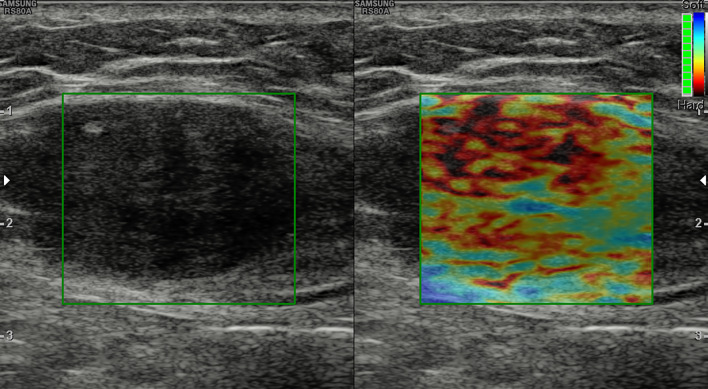

Sonoelastography allows the subjective or objective (strain ratio, SR) analysis of the stiffness patterns of the lesion and the surrounding tissues: whether soft or hard and homogeneous or heterogeneous (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Abdominal wall desmoid tumor. Ill-defined, heterogeneous mass within the rectus muscle. The lesion is mostly stiff at elastography (red and brown colors of the elasticity scale)

Pass et al. prospectively evaluated 105 consecutive soft-tissue masses referred for biopsy within a specialist sarcoma center. Patients underwent B-mode, quantitative (m/s) and qualitative (color map) shear wave elastography. These authors failed to identify any statistically significant association between shear wave velocity and malignancy [37]. Li et al. obtained different results when they performed an evaluation of 61 patients with superficial masses and found significantly increased strain ratio values and elastic scores in the malignant masses. With an SR of > 2.3 as the optimal threshold value, the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing a malignant mass were 94% and 80.5%, respectively; while using an elastic score of ≥ 3 as the optimal threshold value, the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing a malignant mass were 100% and 52%, respectively [38]. Park et al. found that superficial epidermal cysts exhibit a softer nature than do malignant tumors but do not have a different SE pattern from other benign tumors [39].

Contrast-enhanced US assessment

Real-time, grayscale, contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) represents a rather sensitive modality in evaluating intralesional microvasculature, even in case of very slow flows. Since the contrast media currently available do not work perfectly at the high frequency needed to explore the superficial structures, however, there is still limited experience with CEUS investigation of soft tissue. CEUS may allow both qualitative and quantitative assessment of intratumorally vascularization. Heterogeneous contrast enhancement is regarded as a feature suspect for malignancy [40] (Fig. 8). Stramare and coworkers evaluated 14 lesions and found a statistically significant difference between benign and malignant lesions in terms of mean times to peak enhancement intensity but not in terms of mean filling times. When schwannomas were analyzed as a separate group, their mean filling time was found to be significantly different from that of the other benign lesions and from that of the group comprising other benign lesions as well as malignant lesions [41]. In addition, according to Gay et al. [42], the area under the curve, the slope, and the peak intensity differ significantly between benign and malignant lesions. The absence of contrast uptake has a sensitivity of 60% and a specificity of 68% for a diagnosis of benignity. De Marchi et al. studied 216 soft-tissue tumors, applying 7 CEUS perfusion patterns and 3 types of vascularization (arterial-venous uptake, absence of uptake). CEUS pattern 6 (inhomogeneous perfusion), arterial uptake, and location in the lower limb were associated with high risk of malignancy [43].

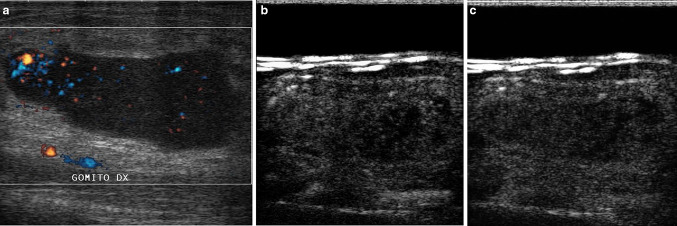

Fig. 8.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as an elbow mass. The enlarged epitrochlear lymph node exhibits some irregular, peripheral flow at directional power-Doppler imaging (s). Discrete, heterogeneous contrast enhancement is seen during the arterial phase of CEUS (13 s after contrast medium injection, b). Marked wash-out is noted during the venous phase (63 s after contrast medium injection, c)

Suspicion of malignancy according to US features

Cases indeterminate at imaging should be managed according to patient history, choosing between US follow-up, MRI assessment, and cytology/histology assessment. A retrospective study reviewed 42 soft-tissue masses (≤ 2 cm) with indeterminate imaging features encountered in a tertiary referral center [44]. Lipomas, synovial cysts, metastases, and cases without histologic confirmation were excluded. There were nine (21%) malignant masses, seven of which were superficial. It was concluded that soft-tissue masses should be managed cautiously when indeterminate at imaging, despite their small size or superficial location.

When a decision of conservative management is made and US monitoring is planned, it is imperative to have an accurate sizing of the lesion, with the maximal diameter traced accurately along the largest sectional view of the lesion and the maximal diameter perpendicular to the first one also measured. Both perpendicular diameters should be seen on a single stored or printed image. The image must be of good quality, with the lesion margins clearly delimited. Repeating the two measurements more than once may be helpful. Measuring a third diameter and calculating the lesion volume or the lesion maximal cross-sectional areas is also useful [5]. At the follow-up US examination, the initial images should be available to use the same scan plane for tracing the measures. Relying only on the previous report may cause incorrect estimation of the lesion growth over time, with consequent incorrect management decisions.

Though most of the lesions will turn out to be benign, a key role for US is to suspect malignancy and prompt direct assessment instead of follow-up [45]. In many cases, patient history, clinical assessment, and US imaging allow enough information to be obtained to rule out malignancy. Lipoma, synovial cyst, vascular malformation, abscess, and hematoma can be diagnosed confidently at US [5, 25]. In one retrospective series, the sensitivity and specificity of the first US diagnosis were 95% and 94%, respectively, for lipoma, 73% and 98% for vascular malformation, 8% and 95% for epidermal cyst, and 69% and 95% for nerve sheath tumor [46]. Improved operator awareness of less-frequently encountered lesions can be of great value in their appropriate US assessment [46].

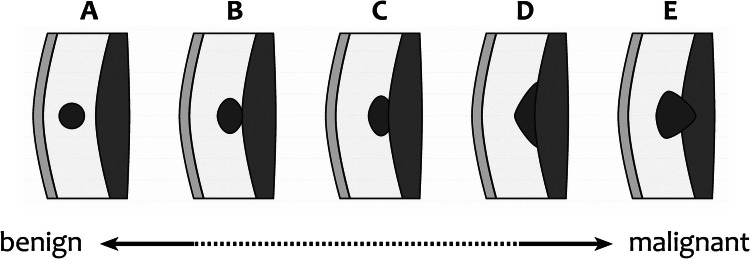

The US findings that might suggest benignity of a soft tissue mass that has a small size, superficial location, homogeneous echo pattern, or hypovascularity. Similar findings, however, can also occur in synovial sarcoma, liposarcoma, melanoma, lymphoma, myeloid sarcoma, and metastasis [32], which of course are less frequent in the population. Mass rupture or combined infection can cause difficulty in differentiating a benign lesion from a malignant one [32]. As a general rule, any new lesion, atypically appearing lesion, or objectively growing lesion must be evaluated carefully. Risk factors for malignancy include the following: patient age above 50 years, previous history of malignancy, obtuse contact angle with the fascia, location below the fascia (intra-muscular), growth beneath the fascia (bicompartmental extension), lesion diameter > 5 cm, a shape taller than it is wide (vertical diameter greater than the transverse diameter), lesion roundness, lobulated shape, indistinct margins, heterogeneous echotexture, intralesional necrotic, hemorrhagic, and/or cystic components, an absence of typical signs of benignity (hair, duct, tail, etc.), poorly defined margins, focal skin thickening, presence of perilesional edema, edema of the fascia, significant displacement/infiltration of the adjacent structures, intense and chaotic intralesional vascularization at color-Doppler (vascular loops, areas of stenosis, occlusions, or unbalanced or irregular vascular branches), high peak velocity values at spectral-Doppler sampling, early, intense, and/or heterogenous lesional perfusion at CEUS, or objective increase in size and/or depth over time [10, 12, 20, 32, 35, 40, 47] (Figs. 9, 10, 11). None of the above-reported features is usually diagnostic for malignancy, but any of them should prompt further assessment. The more risk factors present, the more additional investigation is needed. In one large, retrospective series, the sensitivity and specificity of US for identifying malignant superficial soft-tissue tumors was 94% and 100%, respectively [46].

Fig. 9.

The risk of malignancy increases with the depth of the lesion location. Drawing from Galant et al. [46], modified

Fig. 10.

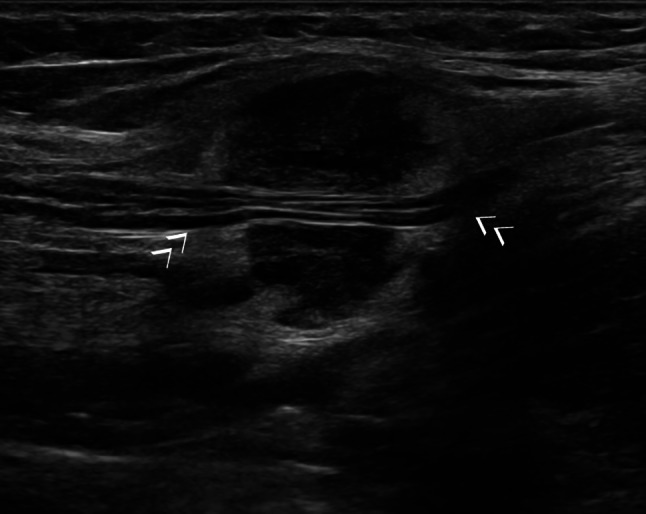

Forearm aggressive fibromatosis encasing the radial artery. Color-Doppler scan

Fig. 11.

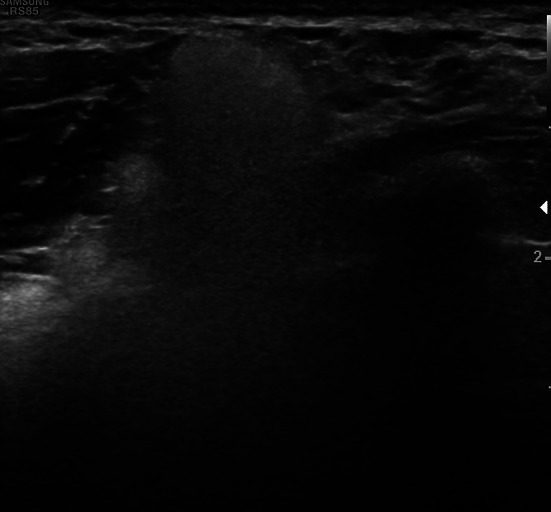

Axillary recurrence of breast cancer with infiltration of the axillary nerve (arrows)

Special body areas

On the scalp, the most frequent lesion is represented by trichilemmal cysts (pilar cysts), either calcified or not [19, 48]. Pilomatricomas present the most common head and neck lesions of the child and young adult, involving the scalp in 9% of cases [19]. Lipomas are frequent, as well as normal or inflamed lymph nodes, particularly in the occipital area. Temporal artery pseudoaneurysms should also be considered [49].

Thoracic wall masses include fluid collections, lipomas, rib cage tumors, and sarcomas [13, 50].

In the abdominal wall, analyzing the location frequently allows, together with the US findings, a definitive diagnosis to be obtained [13, 51–53]. A median bulging is usually due to a hernia, while typical recti muscle sheath abnormalities include hematoma and desmoid tumor. A small mass below the sternum may simply be the xyphoid appendix itself, particularly when it has a curved shape and when the patient has undergone a relevant weight reduction. A Cesarean scar endometriosis can be diagnosed easily based on patient history and symptoms [29]. This, despite the discrete vascularization of these nodules, could be misleading. Tumor implants and umbilical metastasis (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) should also be considered.

Scapular region and shoulder girdle masses include bursitis, acromioclavicular cysts, paralabral cysts, fluid collections, lipomas, elastofibroma dorsi, sarcomas, and masses of bony or cartilaginous origin [13, 25, 54].

Axillary masses include lymphadenopathies, suppurative hidradenitis changes, epidermal cysts, lipomas (and fatty accumulation), siliconomas (breast implant rupture), accessory breast tissue (and related focal abnormalities) [13, 55, 56] (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Palpable axillary mass. The classical snowstorm pattern indicates silicone-filled lymph nodes due to breast implant rupture. The patient was unaware of the rupture of the prosthesis before US and mentioned the presence of the implant only when asked

Elbow masses include epitrochlear lymphadenopathies, epidermal cysts, olecranon bursitis, calcinosis, lipomas, desmoids, and peripheral nerve sheath tumors [57, 58].

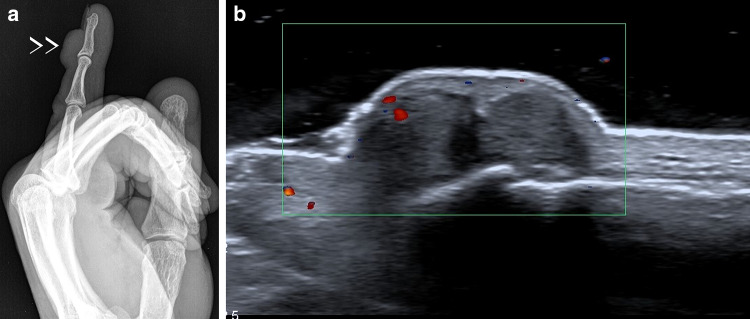

Wrist and hand masses account for 13% of soft-tissue tumors [30] (Figs. 13, 14). These lesions can be benign (76.5%) or malignant (12%) or can be pseudomasses (11%) [30]. Cysts account for 60% of hand masses, with 95% of them being typical at US [30, 59]. In a large Indian series on hand and wrist lesions submitted to FNA, 12% were diagnosed as inflammatory, 77% as benign non-neoplastic, and 11% as neoplastic (benign or malignant). The most frequent inflammatory lesions included synovitis, tuberculosis, and abscess. In the benign, non-neoplastic (tumor-like) lesions, the most common lesion was ganglion (synovial cyst). The most frequent neoplastic lesion was giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath [45]. In an US series, there were six lipomas, six ganglion cysts, three neurilemmomas, three neurofibromas, ten giant cell tumor, two tenosynovitis lesions, and one malignant lymphoma [60]. In a retrospective surgical series on deep palmar lesions, all 48 abnormalities were benign. Histopathologic diagnoses were ten lipomas, eight ganglions, five giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath, four schwannomas, three hemangiomas, three palmar fibromatosis, two epidermal cysts, two neurofibroma, one angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, one granuloma, one calcifying aponeurotic fibroma, one digital fibroma, one foreign body granuloma, and one lipofibromatous hamartoma [61]. The epidermal cysts of the hands are usually found over the palm. In the finger, they arise in the terminal phalanx, while the lateral border of the sole is the most common site of the plantar epidermal cyst [22].

Fig. 13.

Palpable mass of the hand dorsum. Painless, four-day lasting swelling in an elderly woman (a). US shows fluid effusion around the extensor tendons due to tenosynovitis (b)

Fig. 14.

Giant-cell tendon sheath tumor of the small finger. X-ray shows dorsal swelling of the distal phalanx, with no calcifications or bony change (a). Power-Doppler scans showed a bilobed hypoechoic nodule without significant flow signals (b)

Inguinal swelling can be due to hernias, lymphadenopathies, suppurative hidradenitis changes, spermatic cord tumors (lipomas, sarcomas, mesotheliomas, etc.), post-puncture femoral artery pseudoaneurysms, iliopsoas bursitis, undescended testis, and bony masses [13, 62].

Masses in the gluteal region can become very large before becoming palpable. Main causes include post-injection abscesses and granulomas, hidradenitis suppurative, epidermal cysts, pilonidal cysts (coccyx), amyloidosis, lateral sacral meningocele, sciatic bursitis, gluteal artery pseudoaneurysms, sciatic nerve masses, rectal duplication cysts, lesions of bone or cartilage origin, and sarcomas [13, 63].

Popliteal fossa masses include bursitis (gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa distention), popliteal artery aneurysms or adventitial cysts, muscle ruptures, lipomas, and synovial sarcomas [13, 64, 65].

The most frequent soft-tissue masses of the foot include synovial cysts (the third-most common location after the wrist and the hand), bursitis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, foreign body granulomas, plantar fibromatosis, and giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath (toe) [66].

US-guided procedures

In cases of suspicious nodules, even if palpation is clear, US-guided sampling is preferred. Pre-procedure US assessment is useful for choosing between fine needle aspiration (FNA) of cytology or core needle biopsy for histology. It also allows the ruling out of lesions that are not candidates for puncture, such as pseudoaneurysms. The color-Doppler evaluation of the overall vascularization of the lesion allows for the appropriate planning for the percutaneous procedure, choosing the appropriate needle size. An US guide allows the critical structures present along the needle path (vessels, nerves, etc.) to be avoided and the most appropriate area of the lesion to be reached, avoiding necrotic, cystic, or hypervascularized areas. CEUS can be even more accurate than US in targeting biopsy [67, 68]. In cases where there is a potential risk of malignant seed in the path of the percutaneous ultrasound procedure, such as for example in sarcomas, the axis of the procedure should be discussed with the surgeon and should be in the same section that will be removed during the surgery [1].

US may also be employed to guide percutaneous drainage, percutaneous therapy, or percutaneous placement of surgical guidewires [69].

Conclusion

Soft-tissue palpable lesions are extremely common in clinical practice, and a systematic clinical and sonographic approach is mandatory for their study. Full-potential (multiparametric) US imaging is needed, including color-power-Doppler, spectral-Doppler, and elastography facilities. The high spatial resolution of ultrasound in the superficial tissues can be a powerful tool for discriminating among the wide range of superficial soft-tissue masses. Epidermal cysts, synovial cysts, bursitis, foreign bodies, lipomas, and pilomatricomas can usually be diagnosed confidently using US (Fig. 15). In some cases, there are overlapping US features among the benign, intermediate, and malignant entities, requiring further imaging. Second-level options include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), FNA, biopsy, and surgical excision [1, 12, 45]. MRI is mandatory in cases of superficial soft-tissue lesions unclear at initial US investigation or in cases suspected of malignancy and consequently requiring local staging [2, 20, 21]. Owing to its high-contrast resolution, MRI is quite specific, and only a small proportion of lesions with indeterminate MRI features will be diagnosed as malignant tumors in the end [70].

Fig. 15.

Palpable, painless thigh nodule in a 9-year-old boy. The classical appearance of a heterogeneous, subcutaneous nodule with hyperechoic, near-calcified center and hypoechoic halo (a) and with discrete intralesional flows at directional power-Doppler (b) should be diagnosed as a pilomatricoma

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Alessandra Trocino, librarian at the National Cancer Institute Fondazione Pascale of Naples, Italy, for the bibliographic assistance.

Abbreviations

- CAD

Computer-assisted diagnosis

- CT

Computed tomography

- FNA

Fine-needle aspiration

- FOV

Field of view

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SR

Strain ratio

- US

Ultrasound

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they did not receive any funding for this study.

Ethical approval

This is a review article. The images included are from our current clinical practice. Anyway, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

This is a review article. The images included are from our current clinical practice. For retrospective chart reviews, the authors obtained the consent requirement to be waived.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Andritscha E, Beishonb M, Bielacc S, et al. ECCO essential requirements for quality cancer care: soft tissue sarcoma in adults and bone sarcoma. A critical review. Critical Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2017;110:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noebauer-Huhmann IM, Weber MA, Lalam RK, et al. Soft tissue tumors in adults: ESSR-approved guidelines for diagnostic imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2015;19:475–482. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1569251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner JM, Rebik K, Spicer PJ. Ultrasound of soft tissue masses and fluid collections. Radiol Clin North Am. 2019;57:657–669. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martorell A, Wortsman X, Alfageme F, Roustan G, Arias-Santiago S, Catalano O, Scotto di Santolo M, Zarchi K, Bouer M, Gaitini D, Gonzalez C, Bard R, García-Martínez FJ, Mandava A. Ultrasound evaluation as a complementary test in hidradenitis suppurativa: proposal of a standardized report. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1065–1073. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierucci A, Teixeira P, Zimmermann V, Sirveaux F, Rios M, Verhaegue JL, Blum A. Tumours and pseudotumours of the soft tissue in adults: perspectives and current role of sonography. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:238–254. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norgan AP, Pritt BS. Parasitic infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25:106–123. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esposito F, Ferrara D, Di Serafino M, Diplomatico M, Vezzali N, Giugliano AM, Colafati GS, Zeccolini M, Tomà P. Classification and ultrasound findings of vascular anomalies in pediatric age: the essential. J Ultrasound. 2019;22:13–25. doi: 10.1007/s40477-018-0342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Józsa L, Renner A. Tumors and tumor-like lesions arising in tendons. A clinicopathological study of 75 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:83–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00393879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jo VY, Fletcher CD. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology. 2014;46:95–104. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaman FD, Kransdorf MJ, Andrews TR, Murphey MD, Arcara LK, Keeling JH. Superficial soft-tissue masses: analysis, diagnosis, and differential considerations. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:509–523. doi: 10.1148/rg.272065082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wortsman X, Jemec GBE (eds) (2013) Dermatologic ultrasound with clinical and histologic correlations. Springer

- 12.Calleja M, Dimigen M, Saifuddin A. MRI of superficial soft tissue masses: analysis of features useful in distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. Skelet Radiol. 2012;41:1517–1524. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catalano O, Nunziata A, Siani A (2009) Fundamentals in oncologic ultrasound. Springer, Italia

- 14.Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD, Wessell DE, et al. Expert panel on musculoskeletal imaging: ACR appropriateness criteria® soft-tissue masses. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:S189–S197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Qattan MM, Al-Namla A, Al-Thunayan A, Al-Subhi F, El-Shayeb AF. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of glomus tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg [Br] 2005;30:535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García Bustos, de Castro A, Ferreirós Domínguez J, Delgado Bolton R, Fernández Pérez C, Cabeza Martínez B, García García-Esquinas M, Carreras Delgado JL. PET-CT in presurgical lymph node staging in non-small cell lung cancer: the importance of false-negative and false-positive findings. Radiologia. 2017;59:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.rx.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Workman RB, Coleman RE. Fundamentals of PET/CT. In: Coleman RE, editor. PET/CT: Essentials for clinical practice. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wortsman X, Wortsman J. Clinical usefulness of variable-frequency ultrasound in localized lesions of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wortsman X, Wortsman J, Matsuoka L, Saavedra T, Mardones F, Saavedra D, Guerrero R, Corredoira Y. Sonography in pathologies of scalp and hair. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:647–655. doi: 10.1259/bjr/22636640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiDomenico P, Middleton W. Sonographic evaluation of palpable superficial masses. Radiol Clin North Am. 2014;52:1295–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD. Imaging of soft-tissue musculoskeletal masses: fundamental concepts. RadioGraphics. 2016;36:1931–1948. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016160084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nigam JS, Bharti JN, Nair V, Gargade CB, Deshpande AH, Dey B, Singh A. Epidermal cysts: a clinicopathological analysis with emphasis on unusual findings. Int J Trichology. 2017;9:108–112. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_16_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma N, Kumar N, Verma R, Jhobta A. Tibialis anterior muscle hernia: a case of chronic, dull pain and swelling in leg diagnosed by dynamic ultrasonography. Pol J Radiol. 2017;82:293–295. doi: 10.12659/PJR.900846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalano O, Alfageme Roldan F, Varelli C, Bard R, Corvino A, Wortsman X. Skin cancer: findings and role of high-resolution ultrasound. J Ultrasound. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00379-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carra BJ, Bui-Mansfield LT, O’Brien SD, Chen DC. Sonography of musculoskeletal soft-tissue masses: techniques, pearls, and pitfalls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1281–1290. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corvino A, Sandomenico F, Corvino F, Campanino MR, Verde F, Giurazza F, Tafuri D, Catalano O (2019) Utility of a gel stand-off pad in the detection of Doppler signal on focal nodular lesions of the skin. J Ultrasound Mar 29. 10.1007/s40477-019-00376-3(Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Catalano O, Setola SV, Vallone P, Mattace Raso M, D’Errico Gallipoli A. Sonography for locoregional staging and follow-up of cutaneous melanoma: how we do it. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:791–802. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catalano O, Sandomenico F, Siani A. Value of the extended field of view modality in the sonographic imaging of cutaneous melanoma: a pictorial essay. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1300–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toprak H, Kiliç E, Serter A, Kocakoç E, Ozgocmen S. Ultrasound and Doppler US in evaluation of superficial soft-tissue lesions. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2014;4:12. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.127965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerini H, Morvan G, Vuillemin V, Campagna R, Thevenin F, Larousserie F, Leclercq C, Le Viet D, Drapé JL. Ultrasound of wrist and hand masses. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:1247–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catalano O, Caracò C, Mozzillo N, Siani A. Locoregional spread of cutaneous melanoma: sonography findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:735–745. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung HW, Cho KH. Ultrasonography of soft tissue “oops lesions”. Ultrasonography. 2015;34:217–225. doi: 10.14366/usg.14068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corvino A, Corvino F, Catalano O, Sandomenico F, Petrillo A. The tail and the string sign: new sonographic features of subcutaneous melanoma metastasis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2017;43:370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiou HJ, Chen CY, Liu TC, Chiou SY, Wang HK, Chou YH, Chiang HK. Computer-aided diagnosis of peripheral soft tissue masses based on ultrasound imaging. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2009;33:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiou HJ, Chou YH, Chiu SY, Wang HK, Chen WM, Chen TH, Chang CY. Differentiation of benign and malignant superficial soft-tissue masses using grayscale and color doppler ultrasonography. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009;72:307–315. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Artul S, Nseir W, Armaly Z, Soudack M. Superb microvascular imaging: added value and novel applications. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2017;7:45. doi: 10.4103/jcis.JCIS_79_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pass B, Jafari M, Rowbotham E, Hensor EM, Gupta H, Robinson P. Do quantitative and qualitative shear wave elastography have a role in evaluating musculoskeletal soft tissue masses? Eur Radiol. 2017;27:723–731. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4427-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S, Liu L, Lv G. Diagnostic value of strain elastography for differentiating benign and malignant soft tissue masses. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:2041–2044. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park HJ, Lee SY, Lee SM, Kim WT, Lee S, Ahn KS. Strain elastography features of epidermoid tumours in superficial soft tissue: differences from other benign soft-tissue tumours and malignant tumours. Br J Radiol. 2015;88:20140797. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruber L, Gruber H, Luger AK, Glodny B, Henninger B, Loizides A. Diagnostic hierarchy of radiological features in soft tissue tumours and proposition of simple diagnostic algorithm to estimate malignant potential of an unknown mass. Eur J Radiol. 2017;95:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stramare R, Gazzola M, Coran A, Sommavilla M, Beltrame V, Gerardi M, Scattolin G, Faccinetto A, Rastrelli M, Grisan E, Montesco MC, Rossi CR, Rubaltelli L. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound findings in soft-tissue lesions: preliminary results. J Ultrasound. 2013;16:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s40477-013-0005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gay F, Pierucci F, Zimmerman V, Lecocq-Teixeira S, Teixeira P, Baumann C, Blum A. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography of peripheral soft-tissue tumors: feasibility study and preliminary results. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Marchi A, Prever EBD, Cavallo F, Pozza S, Linari A, Lombardo P, Comandone A, Piana R, Faletti C. Perfusion pattern and time of vascularisation with CEUS increase accuracy in differentiating between benign and malignant tumours in 216 musculoskeletal soft tissue masses. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pham K, Ezuddin NS, Pretell-Mazzini J, Subhawong TK (2019) Small soft tissue masses indeterminate at imaging: histological diagnoses at a tertiary orthopedic oncology clinic. Skeletal Radiol Mar 22. 10.1007/s00256-019-03205-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Goyal A, Pathak P, Sharma P, Sharma S. Role of FNAC in diagnosing lesions of hand and wrist. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:853–858. doi: 10.1002/dc.24050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hung EH, Griffith JF, Ng AW, Lee RK, Lau DT, Leung JC. Ultrasound of musculoskeletal soft-tissue tumors superficial to the investing fascia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:W532–W540. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galant J, Martí-Bonmatí L, Soler R, Saez F, Lafuente J, Bonmatì C, Gonzalez I. Grading of subcutaneous soft tissue tumors by means of their relationship with the superficial fascia on MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:657–663. doi: 10.1007/s002560050455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, Zhao B, Chen W, Xu Y. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic features. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91–96. doi: 10.1002/jum.14666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corvino A, Catalano O, Corvino F, Sandomenico F, Setola SV, Petrillo A. Superficial temporal artery pseudoaneurysm: what is the role of ultrasound? J Ultrasound. 2016;19:197–201. doi: 10.1007/s40477-016-0211-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Souza FF, de Angelo M, O’Regan K, Jagannathan J, Krajewski K, Ramaiya N. Malignant primary chest wall neoplasms: a pictorial review of imaging findings. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gokhale S. Sonography in identification of abdominal wall lesions presenting as palpable masses. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1199–1209. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.9.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bashir U, Moskovic E, Strauss D, Hayes A, Thway K, Pope R, Messiou C. Soft-tissue masses in the abdominal wall. Clin Radiol. 2014;69:e422–e431. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahn SE, Park SJ, Moon SK, Lee DH, Lim JW. Sonography of abdominal wall masses and masslike lesions: correlation with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:189–208. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.03027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harish S, Saifuddin A, Bearcroft PW. Soft-tissue masses in the shoulder girdle: an imaging perspective. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:768–783. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.An JK, Oh KK, Jung WH. Soft-tissue axillary masses (excluding metastases from breast cancer): sonographic appearances and correlative imaging. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:288–297. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oliff MC, Birdwell RL, Raza S, Giess CS. The breast imager’s approach to nonmammary masses at breast and axillary us: imaging technique, clues to origin, and management. RadioGraphics. 2016;36:7–18. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Catalano O, Nunziata A, Saturnino PP, Siani A. Epitrochlear lymph nodes: anatomy, clinical aspects, and sonography features. Pictorial essay. J Ultrasound. 2010;13:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JY, Kim SM, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA. Sonography of benign palpable masses of the elbow. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:1113–1119. doi: 10.7863/jum.2011.30.8.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teh J. Ultrasound of soft tissue masses of the hand. J Ultrason. 2012;12:381–401. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng JW, Tang SF, Yu TY, Chou SW, Wong AM, Tsai WC. Sonographic features of soft tissue tumors in the hand and forearm. Chang Gung Med J. 2007;30:547–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozcanli H, Ozaksar K, Cavit A, Gurer EI, Cevikol C, Ada S. Deep palmar tumorous conditions of the hand. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27:2309499019840736. doi: 10.1177/2309499019840736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oh SN, Jung SE, Rha SE, Lim GY, Ku YM, Byun JY, Lee JM. Sonography of various cystic masses of the female groin. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1735–1742. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.12.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bloem JL, Reidsma II. Bone and soft tissue tumors of hip and pelvis. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:3793–3801. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.03.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pathria MN, Zlatkin M, Sartoris DJ, Scheible W, Resnick D. Ultrasonography of the popliteal fossa and lower extremities. Radiol Clin North Am. 1988;26:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toolanen G, Lorentzon R, Friberg S, Dahlström H, Oberg L. Sonography of popliteal masses. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;59:294–296. doi: 10.3109/17453678809149366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ganguly A, Aniq H, Skiadas B. Lumps and bumps around the foot and ankle: an assessment of frequency with ultrasound and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:1051–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1575-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Marchi A, Brach del Prever EM, Linari A, Pozza S, Verga L, Albertini U, Forni M, Gino GC, Comandone A, Brach del Prever AM, Piana R, Faletti C. Accuracy of core-needle biopsy after contrast-enhanced ultrasound in soft-tissue tumours. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2740–2748. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1847-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coran A, Di Maggio A, Rastrelli M, Alberioli E, Attar S, Ortolan P, Bortolanza C, Tosi A, Montesco MC, Bezzon E, Rossi CR, Stramare R. Core needle biopsy of soft tissue tumors, CEUS vs US guided: a pilot study. J Ultrasound. 2015;18:335–342. doi: 10.1007/s40477-015-0161-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Voit C, Proebstle TM, Winter H, Kimmritz J, Kron M, Sterry W, Schwürzer M. Presurgical ultrasound-guided anchor-wire marking of soft tissue metastases in stage III melanoma patients. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:129–132. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khoo M, Pressney I, Hargunani R, Saifuddin A. Small, superficial, indeterminate soft-tissue lesions as suspected sarcomas: is primary excision biopsy suitable? Skelet Radiol. 2017;46:919–924. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]