Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the effectiveness of sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve at the first operation for closed humeral fracture cases.

Methods

Seventeen cases of closed humeral fractures were included in this study. These cases were categorized into two groups: Group P, consisting of seven cases with complete radial nerve palsy after the injuries; and Group C, consisting of ten cases without radial nerve palsy after the injuries. Sonographic evaluation of the condition of the radial nerve was performed before or after open or closed reduction and internal fixation (ORIF or CRIF) during the first operation.

Results

Five of seven Query ID="Q2" Text=" As keywords are mandatory for this journal, please provide 3-6 keywords." cases in Group P showed entrapment or compression of the radial nerve at fracture sites with sonography. Simultaneous radial nerve exploration (SRNE) confirmed sonographic findings in these five cases. The other two cases showed no abnormal sonographic findings except swelling of the radial nerve. CLIF without SRNE was selected and additional sonographic reevaluation of the nerve after CRIF confirmed there were no iatrogenic nerve injuries in these two cases. All of the ten cases in Group C showed no abnormal sonographic findings of the radial nerve. Five of these ten cases selected ORIF, exposed the nerve at the time of approaching the fracture site, and matched sonographic findings. The other five cases without exposure of the nerve confirmed no iatrogenic radial nerve injuries with additional sonographic reevaluation after ORIF or CRIF. All cases in Group P had complete resolution of radial nerve palsy within 4 months postoperatively, and no case in Group C had postoperative iatrogenic radial nerve palsy.

Conclusions

Sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve at the first operation was a useful method to detect conditions of the nerve which can prevent compression or entrapment of the nerve and the need for secondary nerve exploration.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Sonography, Radial nerve, Humeral fracture

Introduction

Radial nerve injuries are common complications associated with closed upper limb injuries such as displaced distal humeral fractures [1–3]. However, there is no consensus on the treatment of these nerve injuries among surgeons. Some surgeons support conservative treatment, as most of these nerve injuries are cases of neurapraxia and resolve spontaneously within 6 months [4–6]. On the other hand, others support early surgical nerve exploration [7–9]. We attribute this discrepancy among surgeons to the few objective methods that are available to observe the condition of the radial nerve.

Some clinical studies suggest that high-resolution ultrasound may be valuable in the pre-operative assessment of traumatic radial nerve neuropathies [1, 10, 11]. However, in most of these studies, sonographic evaluation was performed after the first operation and required a second operation for treatment of the nerve palsy. We hypothesize that sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve under general anesthesia (UGA) during the first operation to perform open or closed reduction and fixation (ORIF or CRIF) for humeral fractures can be a useful method to avoid a second surgery for nerve exploration. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve UGA during the first operation for cases of upper limb fractures.

Methods

From March 2013 to July 2018, 17 cases with traumatic humeral fractures were evaluated the radial nerve condition by sonography UGA in the operating room at the first operation for ORIF or CRIF. All of these cases were included in this study. These cases were categorized into two groups: Group P, consisting of seven cases with complete radial nerve palsy after the injuries; and Group C, consisting of 10 cases without radial nerve palsy after the injuries. We retrospectively reviewed medical records of sonographic examinations, operative findings, and final results of these cases. This study was approved by the institutional review board and informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Group P

All of the seven cases were male, and their mean age was 34.7 years (5–77 years). Three cases had closed supracondylar humerus fractures (Cases 1–3), three cases had closed humeral diaphyseal fractures (Cases 4–6), and one case had a closed avulsion fracture of the lateral ligamentous complex with elbow dislocation (Case 7). In all three supracondylar humerus fracture cases (Cases 1–3), the mechanism of injury was a fall from a height, the fracture type was the extension type (Gartland type III) [12] and the displacement of the distal fragment was posterior and medial (Figs. 1a, 2a), which is commonly associated with radial nerve injury [4, 13].

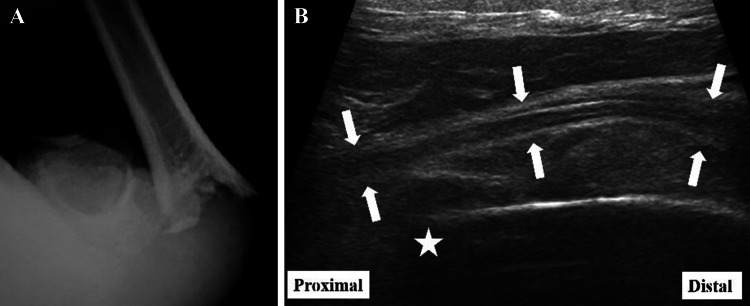

Fig. 1.

Case 9: 10-year-old boy with supracondylar humerus fracture without the complete radial nerve palsy. a Anteroposterior X-ray showed a Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fracture. b The longitudinal sonography of the radial nerve (white arrows) showed the nerve had a normal fibrillar pattern and no contact with the fragment at the fracture site (white star)

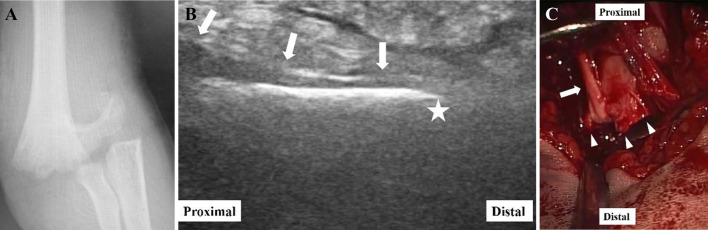

Fig. 2.

Case 1: 5-year-old boy with complete radial nerve palsy. a Anteroposterior X-ray showed a Gartland type III supracondylar humerus fracture. b The longitudinal sonography of the radial nerve (white arrows) showed the nerve became thinner as it got close to the fracture site and suddenly disappeared at the fracture site (white star). The nerve appeared hypoechoic and had a loss of the normal fibrillar pattern. c Operative findings showed the radial nerve (white arrow) was entrapped by spikes (white arrow heads) of the edge of the proximal fragment and was tightly bent about 90° in the posterior direction

In two of three cases of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Cases 4, 5), the cause of the injuries was arm wrestling, and the fractures were at the junction of the middle and distal thirds. They were spiral fractures with distal fragments displaced proximally and radially (Fig. 3a). This pattern is also typically associated with radial nerve injury [2]. These five cases were isolated injuries.

Fig. 3.

Case 5: 51-year-old man with complete radial nerve palsy. a Anteroposterior X-ray showed a displaced spiral distal third humerus diaphyseal fracture. b The longitudinal sonography of the radial nerve (white arrows) showed the nerve was compressed by the edge of the distal humerus fragment (white star) from the bottom and became flattened at the fracture site. c Operative findings showed the radial nerve (white arrow) was compressed by the edge of the distal fragment (white arrow head) from the bottom

On the other hand, in the case of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Case 6) and the case of avulsion fracture of the lateral ligamentous complex with elbow dislocation (Case 7), the cause of injury was motor vehicle accident. These two cases had a high-energy injury and associated injuries. In Case 6, the humerus diaphyseal fracture was at the middle third and transverse. An open fracture of the capitulum of humerus, closed incomplete humeral transcondylar fracture, and skin avulsion of proximal forearm were associated with the fracture. In Case 7, an elbow dislocation occurred in the posterolateral direction, and open diaphyseal forearm fractures were associated (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Case 7: 62-year-old man with complete radial nerve palsy. a Lateral X-ray showed elbow dislocation with forearm diaphyseal fractures. b The longitudinal sonography of the radial nerve (white arrows) showed the nerve had the normal fibrillar pattern; however, it was enlarged compared to c the opposite side (white arrows)

Complete radial nerve palsy was confirmed in these seven cases on arrival. From the findings of sonography of the radial nerve, five cases (Cases 1–5) underwent simultaneous surgical radial nerve explorations (SSRNE) with ORIF, and the other two cases (Cases 6, 7) underwent ORIF or CRIF without SSRNE.

In the three patients with supracondylar humerus fractures (Cases 1–3), radial nerve palsy was confirmed by only touch sensation and motor strength because they were pediatric patients and were not fit for invasive examinations such as electromyography. However, in the other four patients (Cases 4–7), electromyographic examination confirmed radial nerve palsy 4–5 weeks postoperatively. Details are shown in Table. 1.

Table 1.

Details of the cases

| Case no. | Sex | Age | Fracture site of humerus | Associated injuries | Sonographic findings of radial nerve | Operation | Exploration of radial nerve | Operative findings of radial nerve | Final result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P group | 1 | Male | 5 | Supracondyle | – |

Thinner proximal to fracture site and disappeared at fracture site Disappeared normal fibrillar pattern proximal to fracture site |

ORIF | + | Kinked by proximal fragment at fracture site | Complete recovery of radial nerve palsy |

| 2 | Male | 9 | Supracondyle | – | Same as case. 1 | ORIF | + | Same as case. 1 | Same as case. 1 | |

| 3 | Male | 8 | Supracondyle | – | Same as case. 1 | ORIF | + | Same as case. 1 | Same as case. 1 | |

| 4 | Male | 31 | Distal diaphyseal | – |

Compressed by distal fragment at fracture site Disappeared normal fibrillar pattern distal to fracture site |

ORIF | + | Compressed by distal fragment | Same as case. 1 | |

| 5 | Male | 51 | Distal diaphyseal | Same | Same as case. 4 | ORIF | + | Same as case. 4 | Same as case. 1 | |

| 6 | Male | 77 | Distal diaphyseal |

Elbow dislocation Open diaphyseal forearm fractures |

Same as case. 6 | CRIF | – | – | Same as case. 1 | |

| 7 | Male | 62 | Lateral epicondyle (avulsion fracture of lateral ligament complex) |

Open fracture of capitulum of humerus Incomplete humeral transcondylar fracture Skin avulsion of proximal forearm |

Swelling Preserve fibrillar pattern |

ORIF | – | – | Same as case. 1 | |

| C group | 8 | Male | 6 | Supracondyle | – |

Normal fibrillar pattern No contact between nerve and fragments |

CRIF | – | – | No secondary radial nerve palsy |

| 9 | Male | 10 | Supracondyle | – | Same as case. 8 | CRIF | – | – | Same as case. 8 | |

| 10 | Male | 10 | Supracondyle | – | Same as case. 8 | CRIF | – | – | Same as case. 8 | |

| 11 | Female | 7 | Supracondyle | – | Same as case. 8 | ORIF | – | – | Same as case. 8 | |

| 12 | Female | 33 | Diaphyseal | – | Same as case. 8 | CRIF | – | – | Same as case. 8 | |

| 13 | Male | 34 | Diaphyseal | – | Same as case. 8 | ORIF | + | Intact | Same as case. 8 | |

| 14 | Male | 27 | Diaphyseal | – | Same as case. 8 | ORIF | + | Intact | Same as case. 8 | |

| 15 | Male | 28 | Diaphyseal | – | Same as case. 8 | ORIF | + | Intact | Same as case. 8 | |

| 16 | Male | 30 | Diaphyseal | Open Monteggia fracture | Same as case. 8 | ORIF | + | Intact | Same as case. 8 | |

| 17 | Male | 28 | Diaphyseal | Brachial artery injury | Same as case. 8 | ORIF | – | – | Same as case. 8 |

Group C

Eight cases were males, and two cases were females with a mean age of 21.0 years (6–34 years). Four cases had closed supracondylar humerus fractures (Cases 8–11), and six cases had closed humeral diaphyseal fractures (Cases 12–17).

In all four cases of supracondylar humerus fracture (Cases 8–11), the mechanism of injury was a fall from a height, and their fracture type was the extension type (Gartland type III)12. The displacement of the distal fragment was posteromedial in three cases and posterolateral in one case.

In four of six cases of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Cases 12–15), the cause of injury was arm wrestling in two, fall from a height in one, and throwing in one case. The fractures were at the junction of the middle and distal thirds, and they were spiral fractures with distal fragments displaced proximally and radially. These eight cases (Cases 8–15) were isolated injuries.

In the other two cases of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Cases 16, 17), the cause of injury was motor vehicle accident. These two cases had high-energy-associated injuries. These humerus diaphyseal fractures were at the middle third and transverse and were associated with an open Monteggia fracture in Case 16 and an injury of the brachial artery in Case 17. Three of four cases of supracondylar humerus fractures (Cases 8–10) and one case of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Case 12) underwent CRIF. The other case of supracondylar humerus fracture and five cases of humerus diaphyseal fractures underwent ORIF. Details are shown in Table 1.

Sonographic examination

In this study, we used two commercial sonographic devices (My Lab Five; Esaote, Florence, Italy or Aplio 300 and Canon Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with 10–18 MHz linear probes. Sonographic evaluation was performed by the first or third author. Both these individuals had over 2 years’ experience of sonographic examinations and were aware of the condition of each patient.

The radial nerve was observed running from the radial groove to the humeroradial joint, at which the radial nerve divides into the superficial radial sensory nerve and posterior interosseous nerve [14]. Axial and longitudinal images of the radial nerve were obtained. Swelling, compression, entrapment, and rupture of the radial nerve were examined.

All cases were evaluated the radial nerve sonographically immediately UGA in an operating room. Depending on sonographic findings, we decided whether SSRNE should be performed or not. When SSRNE was performed, we compared between sonographic and operative findings. On the other hand, when SSRNE was not performed, sonographic reevaluation was added after CRIF or ORIF to confirm that an iatrogenic radial nerve injury would not be caused by these procedures.

The authors have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Results

Sonographic findings

In the C group, axial and longitudinal ultrasonographic scans of the radial nerve showed a normal fibrillar pattern, no swelling, and no contact between the humeral bone fragments and the radial nerve at the fracture site (Fig. 1b). In four cases of supracondylar humerus fractures (Cases 8–11) and two cases of humerus diaphyseal fractures (Cases 12, 17), SSRNE was not performed and sonographic reevaluation of the radial nerve after CRIF or ORIF confirmed there was no change in the condition of the radial nerve due to these procedures.

On the other hand, in the P group, three cases with supracondylar humerus fractures (Cases 1–3) had abnormal radial nerve observations. The radial nerve was in contact with the volar surface of the cortex of the proximal humeral fragment. It became thinner as it approached the fracture site and suddenly disappeared at the fracture site. In addition, the nerve appeared hypoechoic and had a loss of its normal fibrillar pattern (Fig. 2b). The radial nerve in two of three cases of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Cases 4, 5) was visualized from the proximal to the distal region of the fracture site. However, it was compressed by the edge of the distal humerus fragment from the bottom and flattened at the fracture site. In addition, the nerve appeared hypoechoic and had a loss of its normal fibrillar pattern around the fracture site (Fig. 3b). In these five cases, SSRNE was performed, and these findings were compared to the sonographic findings. However, in the other case of humerus diaphyseal fracture (Case 6) and the case of elbow dislocation (Case 7), the radial nerve was swelling (Fig. 4b) compared to the opposite side (Fig. 4c), but it had a normal fibrillar pattern and no compression along it (Fig. 4b). In these two cases, SSRNE was not performed and sonographic reevaluation of the radial nerve after ORIF or CRIF (intramedullary nail fixation in Case 6) confirmed no change in the condition of the radial nerve from these procedures. Details are shown in Table 1.

Operative findings

In Group C, five of six cases of humerus diaphyseal fracture cases (Cases 13–17) received ORIF depending on the backgrounds of each case such as age and fracture type, although sonographic findings of the radial nerve were judged as normal. In four of these five cases (Cases 13–16), the radial nerve was observed to reach the fracture site directly from the posterior approach, and the macroscopic findings of the nerve corresponded with sonographic findings in these cases. In Group P, SSRNE was performed in five cases with radial nerve palsy (Cases 1–5). The operative findings corresponded with the sonographic findings in all five cases. In the three cases of supracondylar humerus fracture (Cases 1–3), the radial nerve ran along the volar cortex of the proximal humerus fragment from the proximal side, was entrapped by spikes of the fragment edge, and was tightly bent about 90° to the posterior direction. However, no rupture of the nerve was observed. Therefore, we resected the fragment spikes and exfoliated the radial nerve from the surrounding soft tissue distally to Frohse’s arcade to loosen the tension of the nerve and release it from the entrapment (Fig. 2c). In two cases of humeral diaphyseal fracture (Cases 4, 5), the radial nerve had no entrapment; however, it was compressed by the edge of the distal fragment from the bottom (Fig. 3c). Details are shown in Table 1.

Postoperative condition

No postoperative complications occurred such as infection and iatrogenic nerve palsy in any case, and bone union was obtained in all cases. In Group P, radial nerve palsy resolved completely within 4 months in all five cases with SSRNE and the two cases without SSRNE.

Discussion

The vast majority of humeral fractures affect the peripheral nerves. The most commonly affected nerve is the radial nerve, with the most common cause of disturbance being a diaphyseal fracture of the humerus [1, 15, 16]. Its relationship with radial nerve injury is due to anatomical factors, as this nerve is fixed near the bone in the middle third to the distal third transition to the humerus [1–3].

For treatment of primary radial nerve palsy with closed humerus fractures, some authors suggest that late surgical exploration of the radial nerve (3–4 months after injuries) is better than SSRNE, because many cases of radial nerve palsy recover spontaneously (approximately 70% of cases without SSRNE); [2, 5, 6, 15] therefore, many cases with radial nerve palsy do not require SSRNE [17]. However, as some cases with late surgical exploration require a second operation that may negatively affect patients, we do not support this suggestion. Avoiding a second operation for late surgical exploration, we have performed sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve UGA before ORIF or CRIF at the first operation in select cases requiring SSRNE in cases with primary radial nerve palsy in this study. Referring to the report of Bonder et al. [1], we set the indications of SSRNE when sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve UGA showed abnormal findings such as compression or entrapment at the fracture site, because spontaneous recovery is unlikely to occur if the radial nerve is lacerated, riding on or pinched between bone fragments, or entrapped in calluses or scars. On the other hand, SSRNE was not performed in cases without sonographic abnormal findings such as those aforementioned except swelling of the nerve because most of those cases can recover conservatively. As a result, all seven cases with the radial nerve palsy recovered completely without a second operation in this study.

Secondary radial nerve palsy after closed reduction or operative management is not uncommon (10–20% of cases) [18]. The pattern and duration of radial nerve recovery in secondary nerve injury were similar to those seen in primary radial nerve palsy, and the treatment was also similar.

Therefore, some cases of secondary radial nerve palsy also required a second operation for late nerve exploration. We have considered avoiding a second surgery for secondary radial nerve palsy, and a lack of entrapment or compression by implants or fracture fragments should be confirmed after ORIF or CRIF during the first operation. Sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve after ORIF or CRIF during the first operation for cases without simultaneous radial nerve exploration was useful to confirm a lack of secondary compression or entrapment of the radial nerve due to ORIF or CRIF in this study. In addition, especially in Case 7, we would have selected intramedullary fixation for a humeral diaphyseal fracture without SSRNE because this case had many associated injuries and we expected that the soft tissues of the affected upper limb would be severely damaged and would need to be treated with a less invasive method. Intramedullary nail fixation is not recommended in primary radial nerve palsies associated with humeral diaphyseal fractures because of the potential for entrapment of the nerve in the fracture site, leaving it vulnerable to further damage during canal preparation and rod insertion [15]. However, the sonographic evaluation before intramedullary nail fixation was able to confirm that there was no entrapment of the nerve at the fracture site and to ensure that intramedullary nail fixation would not lead to further damage to the nerve.

In our cases with radial nerve palsy, the operative and sonographic findings matched. Therefore, we believe that sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve can detect the existence of nerve compression or entrapment correctly. As such, surgeons should perform sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve intraoperatively in the first operation, even with a closed reduction and fixation without SSRNE, to confirm the absence of radial nerve compression or entrapment at the fracture site. We believe that this evaluation can decrease secondary operations for radial nerve exploration.

There are some methods to diagnose peripheral nerve lesions. Electromyography and nerve conduction studies are useful methods to diagnose the existence of nerve palsies, but they may not yield reliable information as to the precise sites of nerve damage, thereby providing insufficient help in determining whether to proceed with conservative or surgical treatment [11]. Imaging examinations are frequently necessary to identify the structures associated with nerve abnormalities [19].

Computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can also be used for neuroradiological imaging of nervous and musculoskeletal tissue. However, these techniques have some difficulties in terms of non-real-time images, and they necessitate reconstruction for determining and distinguishing the nerves [20].

We recommend that nerve palsies with closed humerus fractures be estimated during the first operation, as mentioned above, and only sonography is possible in these cases as it is a real-time and mobile image processing technique [20].

This study has some limitations. First, the sample size is small, and the study is retrospective. Second, sonographic evaluation of peripheral nerve conditions requires an operator who is skilled in the sonographic anatomy of the peripheral nerve, and this technique also requires high-frequency linear-array transducers because the ability of sonography to detect peripheral nerves is reduced, especially when the nerve lies deeper than 3 cm and a linear array probe of less than 7 MHz is used [11].

Few cases have undertaken sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve immediately after humerus fractures (within a week) in previous reports. We consider one of the reasons for this to be that the pain is so severe immediately after the injuries, and it is difficult to perform sonographic evaluation of the radial nerve without anesthesia. Another reason is that soft tissues around the radial nerve in particular swell immediately after the injuries. This makes it is difficult to detect the nerve with sonography, and high-frequency probes with more spatial and contrast resolution are required.

The frequency of the probe in our study was 10–18 MHz, higher than that used in previous studies (5–12 MHz) [1, 10, 21]. Bodner et al. [1] described that “upcoming technical developments will improve the spatial resolution and lead to a more accurate delineation of abnormal peripheral nerve conditions.” As they described, we believe the developments reported in this study make it possible to detect radial nerve condition immediately after humerus fractures.

Conclusions

Ultrasonographic evaluation of radial nerve palsy associated with humerus fractures in the first operation is a useful method to decide to perform simultaneous radial nerve exploration for cases with primary radial nerve palsy, to confirm the absence of secondary radial nerve palsy in cases with open or closed reduction and fixation without simultaneous radial nerve exploration, and to decrease the number of cases requiring a second operation for radial nerve exploration.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bodner G, Buchberger W, Schocke M, et al. Radial nerve palsy associated with humeral shaft fracture: evaluation with US-initial experience. Radiology. 2001;219(3):811–816. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.3.r01jn09811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bumbasirevic M, Palibrk T, Lesic A, et al. Radial nerve palsy. EFFORT Open Rev. 2017;27(1):286–294. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.1.000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ricci FPFM, Barbosa RI, Elui VMC, et al. Radial nerve injury associated with humeral shaft fracture: a retrospective study. Acta Orthop Bras. 2015;23(1):19–21. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0836-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louahem DM, Nebunescu A, Canavese F, et al. Neurovascular complications and severe displacement in supracondylar humerus fractures in children: defensive or offensive strategy? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15(1):51–57. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollock F, Drake D, Novill EG, et al. Treatment of radial neuropathy associated with fractures of the humerus. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1981;63(2):239–243. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramachandran M, Birch R, Eastwood DM. Clinical outcome of nerve injuries associated with supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children: the experience of a specialist referral centre. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2006;88(1):90–94. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han SH, Hong IT, Lee HJ, et al. Primary exploration for radial nerve palsy associated with unstable closed humeral shaft fracture. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahl Derg. 2017;23(5):405–409. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2017.26517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keighley G, Hermans D, Lawton V, et al. Radial nerve palsy in mid/distal humeral fractures: is early exploration effective? ANZ J Surg. 2018;88(3):228–231. doi: 10.1111/ans.14259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwok HY, Silk ZM, Quick TJ, et al. Nerve injuries associated with supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children: our experience in a specialist peripheral nerve injury unit. Bone Jt J. 2016;98(6):851–856. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B6.35686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee FC, Singh H, Nazarian LN, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis and intraoperative management of peripheral nerve lesions. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(1):206–211. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.JNS091324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toros T, Karabay N, Özaksar K, et al. Evaluation of peripheral nerves of the upper limb with ultrasonography: a comparison of ultrasonographic examination and the intra-operative findings. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2009;91(6):762–765. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gartland JJ. Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1959;109(2):145–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyons ST, Quinn M, Stanitski CL. Neurovascular injuries in type III humeral supracondylar fractures in children. Clin Orthop and Rel Res. 2000;376:62–67. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigues J, Santos-Faria D, et al. Sonoanatomy of anterior forearm muscles. J Ultrasound. 2019;22(3):401–405. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang G, Ilyas AM. Radial nerve palsy after humeral shaft fractures: the case for early exploration and a new classification to guide treatment and prognosis. Hand Clin. 2018;34(1):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ring D, Chin K, Jupiter JB. Radial nerve palsy associated with high-energy humeral shaft fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(1):144–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, et al. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: a systematic review. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2005;87(12):1647–1652. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B12.16132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaishya R, Kandel IS, Agarwal AK, et al. Is early exploration of secondary radial nerve injury in patients with humerus shaft fracture justified? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019;10(3):535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draghi F, Bortolotto C, Ballerini D, et al. Ultrasonography of the ulnar nerve in the elbow: video article. J Ultrasound. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40477-020-00451-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cokluck C, Aydin K. Ultrasound examination in the surgical treatment for upper extremity peripheral nerve injuries: part I. Turk Neurosurg. 2007;17(4):277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altay MA, Erturk C, Altay M, et al. Ultrasonographic examination of the radial and ulnar nerves after percutaneous cross-wiring of supracondylar humerus fractures in children: a prospective, randomized controlled study. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2011;20(5):334–340. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e32834534e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]