Abstract

This meta-analysis assesses oncologic phase 3 trials using a mandatory web-based registration database as a means of identifying and quantifying factors associated with accrual completion.

Poor accrual is the leading cause of cancer clinical trial failure, most commonly affecting late-phase trials, but the factors associated with successful accrual remain poorly understood.1,2,3 We therefore sought to evaluate oncologic phase 3 trials using a mandatory web-based registration database as a means of identifying and quantifying factors associated with accrual completion.

Methods

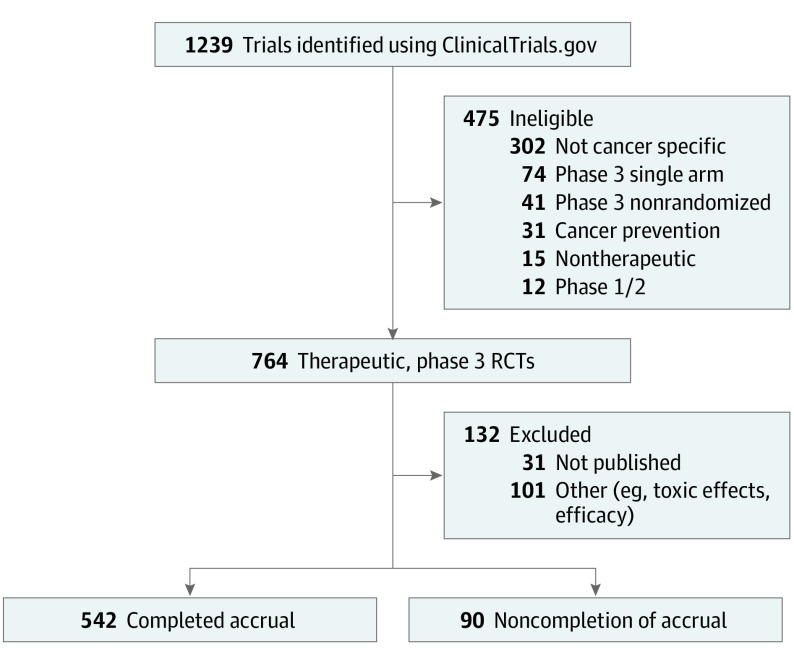

ClinicalTrials.gov was searched using the following parameters: term: cancer; status: excluded not yet recruiting; phase: 3; and study results: with results. The search yielded 1239 trials, which were screened for eligibility to generate a final cohort of 764 cancer-specific, phase 3, randomized, multiarm trials testing a therapeutic intervention from 1991 to 2015 (Figure). Data abstraction for eligible trials was finalized in November 2019. Completion was defined as actual patient enrollment greater than or equal to planned enrollment as per ClinicalTrials.gov, or if the primary end point article publication indicated that targeted accrual or event goals were met. Noncompletion was based on closure of trial with incomplete accrual as indicated by ClinicalTrials.gov or, if available, article publication. Trials were excluded if closure was due to non–accrual-related factors (eg, toxic effects, efficacy), or if accrual was not cited as the reason for trial failure and there was no primary end point publication available to confirm accrual numbers (Figure). Pearson χ2 and binary logistic regression analyses were performed using SPSS, version 24.0 (IBM); all P values were 2-sided and significance was set at P < .05. Institutional review board approval was waived because all data used were publicly available.

Figure. Flowchart of Trial Screening and Inclusion.

Of 1239 trials identified, 475 were ineligible, for a final total of 764 phase 3, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with an interventional and therapeutic intent. Of those, 132 were excluded, to arrive at 542 trials that completed accrual and 90 that had noncompletion of accrual.

Results

Out of 764 eligible trials, 132 were excluded primarily as a result of factors not related to accrual (Figure). Of 632 included trials, 542 (85.8%, total enrollment 396 763 patients) completed accrual, and 90 (14.2%, total enrollment 11 790 patients) did not. Industry sponsorship was associated with successful accrual, as 445 of 485 industry-sponsored trials (91.8%) completed accrual, in contrast with 97 of 147 studies without industry support (66.0%; P < .001) (Table). Moreover, multi-institutional enrollment, multinational enrollment, and trials assessing metastatic disease were all associated with completed accrual (Table). On multiple binary logistic regression analysis, industry sponsorship (odds ratio, 6.64; 95% CI, 2.93-15.08; P < 0.001) and multi-institutional setting (odds ratio, 5.61; 95% CI, 1.86-16.88; P = 0.002) were independently associated with accrual completion.

Table. Trial Factors Associated With Accrual Completion.

| Trial characteristic | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accrual completion (n = 542) | Incomplete accrual (n = 90) | ||

| Industry sponsorship | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 445 (82.1) | 40 (44.4) | |

| No | 97 (17.9) | 50 (55.6) | |

| Cooperative group sponsorship | .07 | ||

| Yes | 142 (26.2) | 32 (35.6) | |

| No | 400 (73.8) | 58 (64.4) | |

| Multi-institutional enrollment | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 515 (95.0) | 63 (70.0) | |

| No | 25 (4.6) | 27 (30.0) | |

| Multinational enrollment | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 412 (76.0) | 35 (38.9) | |

| No | 130 (24.0) | 55 (61.1) | |

| Metastatic disease | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 294 (54.2) | 32 (35.6) | |

| No | 88 (16.2) | 27 (30.0) | |

| Treatment modalityb | .01 | ||

| Systemic | 421 (77.7) | 61 (67.8) | |

| Supportive care | 104 (19.2) | 22 (24.4) | |

| Radiation | 12 (2.2) | 7 (7.8) | |

| Surgery | 5 (0.9) | 0 | |

| Disease site | .67 | ||

| Hematologic | 106 (19.6) | 21 (23.3) | |

| Breast | 96 (17.7) | 11 (12.2) | |

| Thoracic | 80 (14.8) | 11 (12.2) | |

| Genitourinary | 68 (12.5) | 14 (15.6) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 68 (12.5) | 10 (11.1) | |

| Other | 124 (22.9) | 23 (25.6) | |

| PS restrictionc | .65 | ||

| Yes (restricted to ECOG PS to 0-1) | 263 (48.5) | 41 (45.6) | |

| No (not restricted to ECOG PS 0-1) | 266 (49.1) | 46 (51.1) | |

| Study design | .91 | ||

| Superiority | 430 (79.3) | 47 (52.2) | |

| Noninferiority | 52 (9.6) | 6 (6.7) | |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status.

P values reflect Pearson χ2 test results comparing trial factors.

Defined as the modality used for the primary intervention and associated randomization of a given trial.

Trials were divided by PS restriction vs no restriction; PS restriction was defined as ECOG PS of 0 to 1 or Karnofsky PS 80 or higher.

Discussion

This analysis of a trial database that included all phase 3 interventional oncologic trials reveals that a substantial minority—14.2%—failed to accrue as targeted. Despite attempts at predictive models and national efforts to curtail poor accrual over the past decade, this suggests little improvement in the previously reported noncompletion rates of 9% to 14%.2,3 Our data demonstrate that accrual success is independently associated with a number of factors, most notably industry sponsorship.

This association of industry support and accrual success is likely multifactorial and may be related to an integrated and efficient infrastructure for clinical trial management; it may also reflect increased funding to assist with research support staff or to offer financial incentives for patient participation.4,5 Alternatively, financial interests may be at play, as there is potential for bias that leads to disproportionately positive results by using surrogate end points that require lower patient accrual.4,5 As industry-funded trials continue to rise, the broader academic community would benefit from understanding and distilling industry methodologies that can improve patient accrual, while avoiding methodological biases.4,6

Limitations of the study include those inherent when using ClinicalTrials.gov. The association of accrual completion among multinational trials should be interpreted with caution, because registration is only mandatory if accrual included centers in the United States. Our search parameters included trials that complied with mandatory results reporting, opening the possibility of having missed noncompliant incompletely accrued trials. Finally, our search may have missed trials that reached a primary end point but continue to accrue patients, or slow-accruing trials that remain open on ClinicalTrials.gov without results reported to date. Moving forward, efforts to understand the basis for improved trial accrual among industry-supported studies may allow for generalizable lessons in avoiding accrual failure.

References

- 1.Tang C, Sherman SI, Price M, et al. Clinical trial characteristics and barriers to participant accrual: the MD Anderson Cancer Center experience over 30 years, a historical foundation for trial improvement. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(6):1414-1421. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stensland KD, McBride RB, Latif A, et al. Adult cancer clinical trials that fail to complete: an epidemic? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(9):dju229. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennette CS, Ramsey SD, McDermott CL, Carlson JJ, Basu A, Veenstra DL. Predicting low accrual in the National Cancer Institute’s Cooperative Group clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(2):djv324. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra SS. MSJAMA: industry funding of clinical trials: benefit or bias? JAMA. 2003;290(1):113-114. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelijns AC, Thier SO. Medical innovation and institutional interdependence: rethinking university–industry connections. JAMA. 2002;287(1):72-77. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth CM, Cescon DW, Wang L, Tannock IF, Krzyzanowska MK. Evolution of the randomized controlled trial in oncology over three decades. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5458-5464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]