Abstract

Thermoresponsive copolymers that exhibit a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) have been exploited to prepare stimuli-responsive materials for a broad range of applications. It is well understood that the LCST of such copolymers can be controlled by tuning molecular weight or through copolymerization of two known thermoresponsive monomers. However, no general methodology has been established to relate polymer properties to their temperature response in solution. Herein, we sought to develop a predictive relationship between polymer hydrophobicity and cloud point temperature (TCP). A series of statistical copolymers were synthesized based on hydrophilic oligoethylene glycol monomethyl ether methacrylate (OEGMA) and hydrophobic alkyl methacrylate monomers and their hydrophobicity was compared using surface area-normalized partition coefficients (log Poct/SA). However, while some insight was gained by comparing TCP and hydrophobicity values, further statistical analysis on both experimental and literature data showed that the molar percentage of comonomer (i.e., grafting density) was the strongest influencer of TCP, regardless of the comonomer used. The lack of dependence of TCP on comonomer chemistry implies that a broad range of functional, thermoresponsive materials can be prepared based on OEGMA by simply tuning grafting density.

The motivation to design polymers to respond to environmental triggers such as light, ultrasound, pH, redox state, or temperature has led to significant advances in the field of stimuli-responsive materials.1−5 These developments have underwritten their application as biosensors,6 coating materials,7 or drug delivery systems.8 Temperature has been most widely studied because of the simplicity of its external application and the availability of methods for tuning polymer thermoresponsiveness.9 Such thermoresponsive polymers typically display two distinct behaviors in solution, known as the upper critical solution temperature (UCST) and lower critical solution temperature (LCST), representing the critical points above and below which the polymer and solvent are completely miscible.10 Polymers that exhibit an LCST transition are soluble below a critical temperature, above which they undergo a phase transition and demix as a result of increased entropy (for further details, see the following representative references).8,11 The LCST transition is particularly attractive for biological applications due to the relatively low temperatures required to elicit response.12

There are several ways to control the LCST of a polymer solution and thus achieve a phase transition at a desired temperature.13−18 The LCST can be tuned via changing polymer molecular weight (MW) or solution concentration or by varying the composition of a copolymer based on two or more monomers (i.e., P(oligoethylene glycol monomethyl ether methacrylate-co-diethylene glycol methacrylate), P(OEGMA-co-DEGMA), Figure 1).19−22 For example, Gibson and co-workers studied the thermoresponsive behavior of a series of P(N-vinylpiperidone) homopolymers with molecular weights ranging from 4.5 to 83 kDa. The authors showed that the cloud point (TCP) of P(N-vinylpiperidone) decreased from 99 to 67 °C with increasing polymer MW.14 Lecommandoux and co-workers investigated the possibility of manipulating the LCST through copolymerization of 2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline (hydrophobic) with 2-methyl-2-oxazoline (hydrophilic). The TCP of the resulting copolymer increased by 21 °C compared with the P(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline) homopolymer due to an overall increase in hydrophilicity.23 However, the scope of monomers known to yield LCST-responsive materials upon copolymerization is currently limited, complicating the design of new and functional polymers with bespoke transition temperatures.

Figure 1.

Previous studies have focused on the influence of MW or composition on LCST. Herein, we investigate how hydrophobicity influences thermoresponsive behavior.

We have had recent success correlating polymer properties such as solubility and self-assembly behavior to descriptors of their hydrophobicity. In particular, the classification of small molecule hydrophobicity using octanol–water partition coefficients (log Poct) has proven exceptionally successful when leveraged to describe polymer phenomena. For example, we demonstrated that surface area-normalized log Poct (log Poct/SA) values provided predictive information to guide the selection of corona- and core-forming monomers for polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) using either reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization or ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP).24,25 Log Poct/SA was also used effectively as a tool to optimize solvent selection for crystallization-driven self-assembly (CDSA) of P(l-lactic acid) (PLLA)-based block copolymers.26 In order to further benefit from the advantages of using this computational tool to dramatically reduce experimental workload, we postulated that it could be exploited to relate polymer chemical structure to TCP.

Herein, we synthesized a series of copolymers of OEGMA and various alkyl methacrylates (RMA, R = methyl, ethyl, n-butyl, n-hexyl, and n-dodecyl (lauryl)) and studied their LCST response. Polymer cloud point temperature (TCP), the temperature at which polymers undergo a solubility-to-insolubility transition,14 was used as a proxy for the LCST. We then attempted to correlate TCP to copolymer hydrophobicity via log Poct/SA to predict TCP of new polymers. Surprisingly, we found log Poct/SA to be a secondary descriptor of TCP for OEGMA copolymers compared to mol % of comonomer. Indeed, copolymer molar composition (which can be viewed through the lens of grafting density) correlated strongly for both copolymers synthesized in this study and for related copolymers identified from previous literature reports. These discoveries highlight the importance of copolymer topology in determining thermal properties and suggest a route to prepare a wide variety of functional, brush-like copolymers with precisely defined TCP values.

In the vast majority of studies regarding the manipulation of the LCST through copolymerization, two monomers known to produce homopolymers with LCSTs are copolymerized to produce statistical copolymers possessing intermediate LCSTs (Figure 1). Luzon, Ramírez-Jiménez, Porsch, Bebis, and Lutz have all reported thermoresponsive copolymers based on OEGMA and DEGMA, where TCP decreased as a linear function of the molar quantity of DEGMA.20,27−30 While numerous studies have been carried out involving the copolymerization of these two monomers, no consensus has been reached regarding the mechanisms underlying the capability to tune the LCST through copolymerization. Compared with their homopolymers, copolymers of the same degree of polymerization (DP) containing two or more thermoresponsive monomers can have different MW, hydrophobicity, surface area, radius of gyration, and so on. It is unclear if a single factor dominates the LCST or a combination of multiple factors. Moreover, parameters that contribute to determining the LCST in one system may not be general for others.

To isolate influence of copolymer hydrophobicity upon TCP, we prepared a series of copolymers of OEGMA and various alkyl methacrylates (RMA), varying the composition within each series by changing the hydrophobic molar composition in order to observe the effect of both alkyl chain length (hydrophobicity) and initial feed ratio. Alkyl methacrylates (e.g., MMA, nBMA, LMA) were selected as comonomers due to their commercial availability, compatibility with polymerization conditions, and simple hydrocarbon side chain structure. Overall copolymer MW and composition range (i.e., targeted hydrophobic mol %) were maintained as consistently as possible across each series.

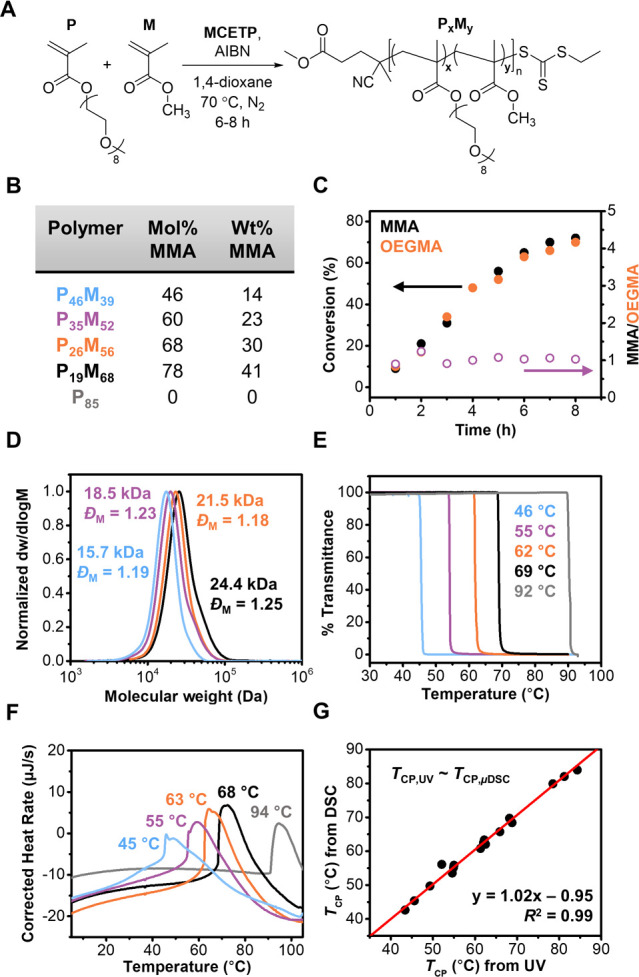

The copolymers were prepared via reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization in 1,4-dioxane for 6–8 h until targeted DPs were reached (Figure 2A). The final molar and mass composition of the purified copolymers were determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy by relative integration of resonances corresponding to each monomer (Figures 2B and S16–S19). Kinetic analysis was conducted to confirm the statistical nature of the copolymerizations. As shown in Figure 2C (and Figures S12–S15), both OEGMA and RMA monomers were consumed at an approximately equal rate. Molecular weight distributions (MWDs) for the P(OEGMA-co-RMA) copolymers were determined using size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). As shown in Figure 2D (and Figures S12–S15), copolymers were obtained with narrow and symmetrical MWDs. Variations in number-average MW (Mn) and dispersity (ĐM) values were determined by calculating coefficients of variance. Using this measure, Mn varied by only 17% across the entire data set, while ĐM varied by 5% with all values <1.40.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative synthetic scheme for the preparation of P(OEGMA-co-RMA) statistical copolymers. MMA is used as the comonomer in this example. (B) Composition of P(OEGMA-co-MMA) copolymers, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. (C) Kinetics of monomer conversion during the synthesis of P(OEGMA-co-MMA) with an initial monomer molar feed ratio of 1:1 OEGMA/MMA. (D) Normalized SEC molecular weight distributions for the P(OEGMA-co-MMA) series (eluent: CHCl3 + 0.5 v/v% NEt3, PS standards). (E) Percent transmittance as a function of temperature for the P(OEGMA-co-MMA) copolymers dissolved in H2O at 5 mg/mL as measured by UV–vis spectroscopy (λ = 550 nm, 20–93 °C, 1 °C min–1). (F) μDSC thermograms for the P(OEGMA-co-MMA) copolymers (3 atm, 0–115 °C, 0.5 °C min–1). (G) Comparison of TCP values measured by UV–vis spectroscopy and μDSC. The solid red line represents a linear fit of the data. The colors in (D), (E), and (F) correspond to those assigned to the various copolymers in (B).

Turbidity measurements were conducted using UV–vis spectroscopy in order to measure the TCP of the copolymers. Changes in the percentage transmittance were recorded at λ = 550 nm within the temperature range of 20 to 93 °C. Temperature points that corresponded to 50% transmittance values were taken as the TCP of polymers (see Supporting Information for the detailed method). In general, TCP decreased for P(OEGMA-co-RMA) copolymers with increasing RMA content (Figure 2E). This inverse relationship was further corroborated by microcalorimetry (μDSC), which measures changes in heat flow as a function of temperature for dilute liquid samples. For these data, the maximum point of the first derivative of the heating traces were chosen as the TCP values. Figure 2F shows a similar decrease in TCP as the hydrophobic content of the copolymers increased. Good agreement between the TCP values obtained from both measurements confirmed their consistency. A similar analysis was performed for the other copolymer series (see Supporting Information).

We next sought to understand the relationship between measured TCP values and copolymer hydrophobicity.

Log Poct, which describes the partitioning of a substance between octanol and water and reflects transfer free energy, was used as the means of quantifying and comparing hydrophobicity.31−33 Toward this end, we calculated log Poct values for short oligomers as proxies for the synthesized copolymers and normalized them with surface areas of optimized conformations using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations (see Supporting Information for the detailed model). We then attempted to relate these calculated log Poct/SA values to measured TCP values.

As shown in Figure 3A, log Poct/SA increased with increasing RMA content, consistent with the established relationship between hydrophobicity and log P. Comonomers with longer alkyl chains had a more dramatic impact on log Poct/SA than those with shorter ones and thus produced relationships with relatively steeper slopes. Figure 3B shows the relationship between TCP and log Poct/SA. Here, inverse linear relationships were observed for each series, confirming our hypothesis that increased copolymer hydrophobicity, resulting from increasing the molar ratio of hydrophobic comonomer in the P(OEGMA-co-RMA) copolymers, acted to decrease TCP. We also hypothesize log Poct/SA values reflect localized degrees of hydrophobicity and the size of the oligomeric models represents a length scale that may not extend to longer range topological influences. As such, each series possessed a unique slope that was related to the alkyl chain length of the comonomer and thus no general correlation could be drawn between copolymer log Poct/SA and TCP.

Figure 3.

(A) Calculated log Poct/SA values for various copolymer oligomers as a function of the mol % of hydrophobic comonomer. (B) Plot of TCP as measured by UV–vis spectroscopy vs log Poct/SA for the same copolymer series.

The complexity of the LCST process was further reinforced by investigating the influence of hydrophobicity on the heat of phase separation (ΔH) calculated from the μDSC data.34 As shown in Figure S22, weak correlations and lack of a general linear relationship were noted between log Poct/SA or polymer composition and ΔH. These data indicate that hydrophobicity contributes to the LCST for statistical copolymers. However, they also imply that a picture of hydrophobicity based on transfer free energy (log P) and conformational insight (SA) only partially captures the LCST process for brush-like copolymers and that other factors must be considered.

The mixing of polymer molecules with H2O, described by ΔGmix, represents a balance of the enthalpically favorable binding of H2O molecules (ΔHmix > 0) and their increased ordering upon binding (ΔSmix > 0). The LCST phenomenon is thus understood as a disruption in the balance of these contributors at higher temperatures, where the entropic term dominates.10,35 Based on this argument and the fact that log P represents a transfer free energy term,36 it was somewhat surprising that a general relationship could not be drawn between copolymer hydrophobicity and TCP, as we anticipated ΔHmix to be directly relatable to hydrophobicity. To better understand determinants of TCP, we searched for relationships involving other polymer descriptors such as molar (mol % RMA) and mass (wt % RMA) composition, Mn, ĐM, and DP.

Figure S1 shows a scatterplot matrix highlighting the intercorrelations between descriptors or correlations with the response variable TCP. It should be noted that data from all of the copolymer series were combined prior to analysis. From these data, relationships were apparent between TCP and each of the descriptors, with the molar and mass compositions exhibiting the strongest correlations. Intriguingly, this initial visualization seemed to imply that the identity (chemistry) of the comonomer was less important in determining TCP than was its quantity in the copolymers. Single and stepwise multivariable linear regression analyses were then applied to the collected data set to develop a quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) model (see SI for full discussion). The model was trained on experimental data using stratified k-fold data sets. An initial optimized model based on two descriptors, the mol % and wt % RMA comonomer, was obtained using either R2 or RMSE as the selection parameter. However, this model was deemed inappropriate due to concerns regarding the influence of collinearity between these parameters on model predictive power for future data sets. Instead, a simplified model using only the mol % of comonomer was adopted, allowing for a simple prediction of TCP based on copolymer composition.

We then sought to validate this simple model against TCP data for OEGMA copolymers in the literature. A total of 94 TCP values for OEGMA copolymers with two different side chain lengths were extracted from about 20 reports.37 These data were selected based on the following criteria: (1) they pertained to OEGMA500/300 statistical copolymers; (2) they included TCP measurements obtained via UV–vis spectroscopy on dilute polymer solutions (i.e., ≤5 mg mL–1) in H2O; (3) the comonomers were ideally simple in structure and/or commercially available; and (4) the comonomers did not possess ionizable groups that would introduce additional stimuli-responsiveness. Comonomers included diethylene glycol methyl ether methacrylate (DEGMA), methyl methacrylate (MMA), N-isopropylacrylamide, pentafluorostyrene (PFS), and others (Figure 4A). Again, the data was visualized using a scatterplot matrix (Figure S4), revealing a similarly strong correlation between TCP and comonomer molar composition. As shown in Figure 4B, linear relationships could generally be drawn between TCP and mol %, with two clusters similar in slope that corresponded to OEGMA copolymers with different OEG side chain lengths. OEGMA300-co-DEGMA copolymers exhibited exceptional behavior, sharing slopes with both clusters depending on composition. Interestingly, the data collected from the literature for OEGMA500 copolymers agreed strongly with our experimental observations (Figure 5A). The same model describing the relationship between TCP and mol % was used to evaluate these literature data. As shown in Figure 5B, this model was reasonably successful in predicting the literature TCP values. This further supported the hypothesis that comonomer chemistry plays a limited role in determining TCP for OEGMA copolymers. Given the “brushy” nature of poly(OEGMA), an increase in comonomer molar quantity can be viewed as a decrease in grafting density. A simple model relating TCP to grafting density may be generally appropriate for other brush copolymers.

Figure 4.

(A) Example comonomers present in P(OEGMA-co-R) copolymers for which TCP values have been measured. (B) Plot of TCP as a function of the molar quantity of comonomer constructed using data collected from literature sources.

Figure 5.

(A) Plot of TCP vs the molar quantity of comonomer. Data from P(OEGMA500-co-R) copolymers obtained from literature sources is overlaid with experimental data from this report. (B) Comparison between literature TCP values and those predicted from molar compositions. The solid red line represents a linear fit of these data.

To conclude, we report the synthesis of a series of P(OEGMA-co-RMA) copolymers via copolymerization of OEGMA and different alkyl methacrylate monomers. LCST behavior of the brush-like copolymers was investigated by using complementary methods. We then attempted to relate TCP to hydrophobicity based on a thermodynamic perspective (log P) and a structural parameter (SA); however, the multifaceted nature of TCP complicated a predictive model. Instead, linear and stepwise regression analysis using a variety of predictors revealed that TCP appeared to depend most significantly on the mol % of comonomer, suggesting that grafting density is the most important determinant of the LCST for OEGMA brush copolymers. Our analysis of both experimental and literature data implies that a wide variety of functional copolymers can be prepared using this guiding principle, as the identity of the comonomer in P(OEGMA-co-R) copolymers does not appear to influence TCP.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Ministry of Turkish Education EPSRC (EP/S00338X/1)), ERC Consolidator Grant (No. 615142), and the University of Birmingham.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00461.

Materials, characterization techniques, experimental procedures, and additional data (statistical analysis, SEC, 1H NMR, μDSC, and UV–vis spectra) (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gibson M. I.; O’Reilly R. K. To aggregate, or not to aggregate? considerations in the design and application of polymeric thermally-responsive nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7204–7213. 10.1039/C3CS60035A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo M.; Yuan J.; Tao L.; Wei Y. Redox-responsive polymers for drug delivery: from molecular design to applications. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 1519–1528. 10.1039/C3PY01192E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manouras T.; Vamvakaki M. Field responsive materials: photo-, electro-, magnetic- and ultrasound-sensitive polymers. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 74–96. 10.1039/C6PY01455K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S.; Ravi P.; Tam K. C. pH-Responsive polymers: synthesis, properties and applications. Soft Matter 2008, 4, 435–449. 10.1039/b714741d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumers J.-M.; Fustin C.-A.; Gohy J.-F. Light-Responsive Block Copolymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 1588–1607. 10.1002/marc.201000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabane E.; Zhang X.; Langowska K.; Palivan C. G.; Meier W. Stimuli-Responsive Polymers and Their Applications in Nanomedicine. Biointerphases 2012, 7, 9. 10.1007/s13758-011-0009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai L. Stimuli-responsive polymer films. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7148–7160. 10.1039/c3cs60023h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawa P.; Pillay V.; Choonara Y. E.; du Toit L. C. Stimuli-responsive polymers and their applications in drug delivery. Biomed. Mater. 2009, 4, 022001. 10.1088/1748-6041/4/2/022001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom R.2 - Temperature-responsive polymers: properties, synthesis and applications. In Smart Polymers and their Applications; Aguilar M. R., San Román J., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2014; pp 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Weber C.; Schubert U. S.; Hoogenboom R. Thermoresponsive polymers with lower critical solution temperature: from fundamental aspects and measuring techniques to recommended turbidimetry conditions. Mater. Horiz. 2017, 4, 109–116. 10.1039/C7MH00016B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg L. E.; Ron E. S. Temperature-responsive gels and thermogelling polymer matrices for protein and peptide delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1998, 31, 197–221. 10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D.; Brooks W. L. A.; Sumerlin B. S. New directions in thermoresponsive polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7214–7243. 10.1039/c3cs35499g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe K.; Neuwirth T.; Czaplewska J.; Gottschaldt M.; Hoogenboom R.; Schubert U. S. Poly(2-oxazoline) glycopolymers with tunable LCST behavior. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 1737–1743. 10.1039/c1py00099c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ieong N. S.; Hasan M.; Phillips D. J.; Saaka Y.; O’Reilly R. K.; Gibson M. I. Polymers with molecular weight dependent LCSTs are essential for cooperative behaviour. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 794–799. 10.1039/c2py00604a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glassner M.; Lava K.; de la Rosa V. R.; Hoogenboom R. Tuning the LCST of poly(2-cyclopropyl-2-oxazoline) via gradient copolymerization with 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 3118–3122. 10.1002/pola.27364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.; Zhou J.; Chi X. Pillar[10]arene-Based Size-Selective Host–Guest Complexation and Its Application in Tuning the LCST Behavior of a Thermoresponsive Polymer. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 36, 23–30. 10.1002/marc.201400570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh R.; Blackman L. D.; Foster J. C.; Varlas S.; O’Reilly R. K. The Importance of Cooperativity in Polymer Blending: Toward Controlling the Thermoresponsive Behavior of Blended Block Copolymer Micelles. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 41, 1900599. 10.1002/marc.201900599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Solorzano I.; Bejagam K. K.; An Y.; Singh S. K.; Deshmukh S. A. Solvation dynamics of N-substituted acrylamide polymers and the importance for phase transition behavior. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 1582–1593. 10.1039/C9SM01798D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenboom R.; Thijs H. M. L.; Jochems M. J. H. C.; van Lankvelt B. M.; Fijten M. W. M.; Schubert U. S. Tuning the LCST of poly(2-oxazoline)s by varying composition and molecular weight: alternatives to poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)?. Chem. Commun. 2008, 5758–5760. 10.1039/b813140f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Jiménez A.; Montoya-Villegas K. A.; Licea-Claverie A.; Gónzalez-Ayón M. A. Tunable Thermo-Responsive Copolymers from DEGMA and OEGMA Synthesized by RAFT Polymerization and the Effect of the Concentration and Saline Phosphate Buffer on its Phase Transition. Polymers 2019, 11, 1657. 10.3390/polym11101657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uǧuzdoǧan E.; Çamli T.; Kabasakal O. S.; Patir S.; Öztürk E.; Denkbaş E. B.; Tuncel A. A new temperature-sensitive polymer: Poly(ethoxypropylacrylamide). Eur. Polym. J. 2005, 41, 2142–2149. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2005.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward M. A.; Georgiou T. K. Thermoresponsive triblock copolymers based on methacrylate monomers: effect of molecular weight and composition. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 2737–2745. 10.1039/c2sm06743a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legros C.; De Pauw-Gillet M.-C.; Tam K. C.; Taton D.; Lecommandoux S. Crystallisation-driven self-assembly of poly(2-isopropyl-2-oxazoline)-block-poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) above the LCST. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 3354–3359. 10.1039/C5SM00313J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. C.; Varlas S.; Couturaud B.; Jones J. R.; Keogh R.; Mathers R. T.; O’Reilly R. K. Predicting Monomers for Use in Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15733–15737. 10.1002/anie.201809614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlas S.; Foster J. C.; Arkinstall L. A.; Jones J. R.; Keogh R.; Mathers R. T.; O’Reilly R. K. Predicting Monomers for Use in Aqueous Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 466–472. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inam M.; Cambridge G.; Pitto-Barry A.; Laker Z. P. L.; Wilson N. R.; Mathers R. T.; Dove A. P.; O’Reilly R. K. 1D vs. 2D shape selectivity in the crystallization-driven self-assembly of polylactide block copolymers. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 4223–4230. 10.1039/C7SC00641A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebis K.; Jones M. W.; Haddleton D. M.; Gibson M. I. Thermoresponsive behaviour of poly[(oligo(ethyleneglycol methacrylate)]s and their protein conjugates: importance of concentration and solvent system. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 975–982. 10.1039/c0py00408a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz J.-F.; Akdemir Ö.; Hoth A. Point by Point Comparison of Two Thermosensitive Polymers Exhibiting a Similar LCST: Is the Age of Poly(NIPAM) Over?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13046–13047. 10.1021/ja065324n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzon M.; Corrales T. Thermal studies and chromium removal efficiency of thermoresponsive hyperbranched copolymers based on PEG-methacrylates. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 116, 401–409. 10.1007/s10973-013-3550-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porsch C.; Hansson S.; Nordgren N.; Malmström E. Thermo-responsive cellulose-based architectures: tailoring LCST using poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylates. Polym. Chem. 2011, 2, 1114–1123. 10.1039/c0py00417k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leo A.; Hansch C.; Elkins D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 525–616. 10.1021/cr60274a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim E.; Dakshinamoorthy D.; Peretic M. J.; Pasquinelli M. A.; Mathers R. T. Synthetic Design of Polyester Electrolytes Guided by Hydrophobicity Calculations. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 7868–7876. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Eloi J.-C.; Harniman R. L.; Richardson R. M.; Whittell G. R.; Mathers R. T.; Dove A. P.; O’Reilly R. K.; Manners I. Uniform Biodegradable Fiber-Like Micelles and Block Comicelles via “Living” Crystallization-Driven Self-Assembly of Poly(l-lactide) Block Copolymers: The Importance of Reducing Unimer Self-Nucleation via Hydrogen Bond Disruption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19088–19098. 10.1021/jacs.9b09885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil H.; Bae Y. H.; Feijen J.; Kim S. W. Effect of comonomer hydrophilicity and ionization on the lower critical solution temperature of N-isopropylacrylamide copolymers. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 2496–2500. 10.1021/ma00062a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. D.; Bedrov D. Roles of Enthalpy, Entropy, and Hydrogen Bonding in the Lower Critical Solution Temperature Behavior of Poly(ethylene oxide)/Water Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 3095–3097. 10.1021/jp0270046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bannan C. C.; Calabró G.; Kyu D. Y.; Mobley D. L. Calculating Partition Coefficients of Small Molecules in Octanol/Water and Cyclohexane/Water. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 4015–4024. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabulated data and their sources can be found in the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.