Abstract

Front-of-package (FOP) food labels are symbols, schemes, or systems designed to communicate concise and useful nutrition-related information to consumers to facilitate healthier food choices. FOP label policies have been implemented internationally that could serve as policy models for the U.S. However, the First Amendment poses a potential obstacle to U.S. government-mandated FOP requirements. We systematically reviewed existing international and major U.S.-based nutrition-related FOP labels to consider potential U.S. policy options and conducted legal research to evaluate the feasibility of mandating a FOP label in the U.S. We identified 24 international and 6 U.S.-based FOP labeling schemes. FOP labels which only disclosed nutrient-specific data would likely meet First Amendment requirements. Certain interpretive FOP labels which provide factual information with colors or designs to assist consumers interpret the information could similarly withstand First Amendment scrutiny, but questions remain regarding whether certain colors or shapes would qualify as controversial and not constitutional. Labels that provide no nutrient information and only an image or icon to characterize the entire product would not likely withstand First Amendment scrutiny.

Keywords: Food labels, front-of-pack, First Amendment

INTRODUCTION

Suboptimal diet is associated with a substantial proportion of diet-related disease in the U.S. (Micha et al. 2017), yet the diets of most Americans remain poor (Rehm et al. 2016). Globally, countries are now considering or have implemented front-of-package (FOP) labels on food products to communicate concise and useful nutrition-related information to consumers (WCRF; L’Abbé et al. 2012; Kanter et al. 2018). Similar labeling policies for the U.S. have been considered but not yet adopted, in part because of legal constraints imposed by the First Amendment. These constraints deserve further analysis, to understand more precisely what is feasible under U.S. law.

Food labels in the U.S. are governed by the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act. This requires a standardized Nutrition Facts label, ingredients list, and allergen information, and that certain health and nutrition claims abide by specific requirements (NLEA 1990). Much of the factual information resides on the back or sides of food packages, and relatively little standardized health-related information is mandated for the front of the package. The U.S. federal government began to explore policy options to create a uniform FOP label in 2009 (IOM 2011). In 2010 and 2011, the Institute of Medicine issued two reports, including a proposed FOP system, and recommended that FOP labels should apply to as many foods as possible and facilitate comparisons of nutritional values within and across food categories (IOM 2011). The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not take action based on these recommendations. In 2018, the FDA announced a Nutrition Innovation Strategy, including a potential voluntary “healthy” FOP icon; it is unclear the extent the FDA will consider a FOP label providing more extensive information or a mandatory FOP label (Federal Register 2018).

A range of FOP labels have become widely used internationally and could be more effective in communicating information and altering consumer behavior, compared with more complex or difficult to see nutrition information and ingredient lists (Lowenstein et al. 2014). In the U.S., voluntary FOP labels or shelf tags are used by some manufacturers and retailers but leave room for consumer confusion in the face of multiple schemes or to determine whether a product did not meet the criteria or whether the manufacturer or retailer did not participate in a particular scheme (Hieke, Harris 2016). This leads to an inability to make comparisons across products or retailers (Draper 2013). Moreover, research indicates that just the presence of the most common voluntary FOP label creates a consumer perception that the product is healthier than it is (Board 2009). Thus, mandatory FOP labels evaluated for efficacy may be relevant.

A mandatory FOP label could encourage consumer reliance on the FOP labeling system across products and companies and could also potentially motivate food manufacturers to reformulate their products, leading to additional health gains (Lowenstein et al. 2014; Talati et al. 2016; Shangguan et al. 2019). Mandatory FOP labeling may address problems of imperfect information for consumers (Wilde 2018), increase competition for healthier products (Duncan 2016), and rectify information asymmetry by providing information up-front to less informed buyers (Lowenstein et al. 2014). Requiring FOP disclosures is also relevant for food because consumer preferences are heterogeneous, labels can be clear and precise because there is a feasible method to establish standards and implement the labeling approach, and there is no political consensus on alternative approaches such as simply requiring manufacturers to improve the healthfulness of their products (Golan et al. 2001).

Many considerations are relevant for the U.S. to formulate a mandatory FOP label policy (Andrews et al. 2011; Roberto et al. 2012; Rahkovsky et al. 2013; Phulkerd et al. 2017), including whether the FOP label is noticed and noticeable by consumers (Bialkova et al. 2013; Becker et al. 2015), presents information that is understood by consumers (IOM 2011; Neal et al. 2017) and effectively supports consumers’ ability to identify unhealthy products (Balcombe et al. 2010) and select healthier products (Rahkovsky et al. 2013; Andrews et al. 2011; Neal et al. 2017). However, legal considerations for the feasibility of the U.S. government mandating specific FOP labels have not been reported. In particular, the First Amendment protects companies from laws that restrict and compel certain types of speech, including on food labels (Rubin v. Coors Brewing 1995; Board of Trustees v. Fox 1989).

The principal display panel (i.e., the front of the package) is a primary location food manufacturers use to market their product. Consequently, any required FOP label that seems to compete or conflict with manufacturers’ desired statements or claims may provide an incentive for manufactures to challenge them in court. The food industry has challenged a whole range of labels under the First Amendment, including calorie disclosure and sodium warning labels on menus (NYSRA v. NYC 2009; NRA v. NYC 2017), and GMO and country-of-origin labels on food products (GMA v. Sorrell 2015; AMI v. USDA 2014). Mandatory FOP labels elicit complex First Amendment questions because they summarize information disclosed in nutrition labeling or provide specific positive or negative interpretive or evaluative information. Therefore, First Amendment considerations related to disclosure requirements are particularly relevant for any governmental policy mandating FOP labels.

To address these gaps in knowledge, this paper reviewed international and U.S.-based FOP labels to identify a range of labeling schemes, which could serve as a model for U.S. FOP policy (Ahmed et al. 2018; Nestle 2013; Hawley et al. 2013). Next, this paper engaged in First Amendment analysis to determine if any of the FOP labels identified could potentially be constitutionally mandated by the federal government on food products in the U.S. This investigation was performed as a part of the Food-PRICE (Policy Review and Intervention Cost-Effectiveness) Project (www.food-price.org).

METHODOLOGY

International and U.S. FOP Labels Identified for Evaluation

To identify examples of FOP policies that theoretically could be adapted in the U.S., we systematically researched all international and U.S. nutrition-related FOP labels, including FOP-like symbols on shelf tags, implemented as of June 30, 2018, using the World Cancer Research Fund International’s NOURISHING framework (WCRF), the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports (IOM 2010; IOM 2012) a presentation on the IOM report (Lichtenstein 2013), and additional online research to gather details of the FOP systems identified (see Appendix). We included industry-designed FOP labels that were voluntarily adopted by the food industry in the U.S. because, unlike other countries, there is no U.S. FOP policy.

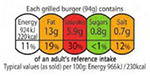

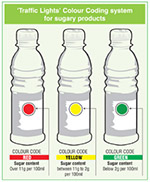

The present evaluation utilized the following definitions to classify FOP labels into three main types: (1)“nutrient-specific data,” disclosing specific nutrient values/content using absolute numbers or percentages per standardized serving or percentage meeting guidelines (e.g., “5 grams saturated fat;” “11% energy”); (2) “interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicators,” interpreting nutrient-specific information, using words, scores, and/or icons (e.g., a low sodium symbol); and (3) “evaluative summary indicators,” evaluating overall food quality or healthfulness using a broad nutrition profile, using words, scores, and/or icons (e.g., an image of a checkmark representing that food meets multiple nutrition criteria for healthy). The second and third types of indicators may or may not incorporate food group ingredient information (e.g., whole grain) depending on the scheme. Hybrid systems combine two or more of the above classifications. All such FOP schemes can be further classified as positive, meaning the FOP label provides positive only information (e.g., a star for healthy); negative, when the FOP label provides a warning or bad score indicating unhealthy (e.g., warning sign); and graded quality, which occurs when a food can earn a specific number of positive marks (e.g., can earn 1 to 5 stars). The absence of a positive mark may indicate something negative about the food (Duncan 2013; Hotz and Xiao 2013) but this was not assessed. This study did not evaluate health or safety warning labels (e.g., the City and County of San Francisco’s warning message that drinking beverages with added sugar(s) contributes to obesity, diabetes, and tooth decay) (SF Ordinance 2015), or FOP labels that solely noted the presence of a food group (e.g., the Whole Grain Stamp (Whole Grain Council)).

For each identified FOP label, data extracted included the FOP name; country or entity proposing or using it; FOP location (on the package or shelf tag); foods to which it applies; whether voluntary or mandatory; type of FOP (nutrient-specific data, interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicator, evaluative summary indicator); and the image of the FOP label to covey visual information, such as colors, illustrations, data, and words. The data extracted was also utilized for First Amendment analysis below. Data were reviewed and extracted by one author (xx) and checked for consistency by the remaining authors.

First Amendment Research

Utilizing LexisNexis, we conducted legal research into First Amendment jurisprudence and law journals evaluating First Amendment case law, published through January 31, 2019, to determine the feasibility of the U.S. federal government requiring food companies to display any of the FOP labels identified above consistent with the First Amendment. We researched First Amendment case law that would be applicable if a mandated FOP label was challenged in court. We focused on Supreme Court precedent, which is binding on all courts. When Supreme Court cases did not provide insight into the relevant legal questions, we researched lower court opinions, specifically focusing on federal appellate (circuit) courts whose legal determinations are binding on lower courts within their jurisdictions and are considered persuasive or influential to courts outside of their jurisdictions.

First Amendment Background

If challenged in court, a properly drafted mandatory FOP label should be analyzed under the test developed in the Supreme Court case, Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel (Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel 1985). Zauderer is applicable when the government compels purely factual information in the commercial context and is the least burdensome test in this context (Pomeranz 2015). Commercial speech is speech that proposes a commercial transaction, such as advertising and labeling, and is principally protected to provide information to consumers (Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel 1985). Under the Zauderer test, the Supreme Court held that commercial disclosure requirements, including warnings and disclaimers, are constitutional if they are (a) “reasonably related to the State’s interest in preventing deception of consumers,” (b) require purely factual, accurate, and uncontroversial information about the product or service itself, and (c) not “unjustified or unduly burdensome (Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel 1985; Milavetz v. U.S. 2010; NIFLA v. Becerra 2018).”

Under the first part of Zauderer, the government must identify a sufficient interest supporting its requirements (Adler 2016). Preventing deception of consumers was confirmed to be a valid government interest in the Zauderer case itself. Notably, each of the federal appellate courts that have expressly considered this requirement have held that the government may require factual disclosures in the commercial context for reasons other than preventing deception of consumers (Pomeranz 2015; ABA v. San Francisco 2019). In the Supreme Court’s most recent case on disclosure requirements, NIFLA v. Becerra, it did not hold otherwise and did not strike down an “informational interest” as inherently unconstitutional (although it found the government did not provide evidence to support such an interest in this particular case) (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018). Thus, this part of the test may be more accurately read as “reasonably related to the State’s interest.”

Second, disclosure requirements must be accurate (Milavetz v. U.S. 2010), factual, and uncontroversial and must be about the product or service itself (Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel 1985; NIFLA v. Becerra 2018). In NIFLA, the Court stated that it does “not question the legality of health and safety warnings long considered permissible, or purely factual and uncontroversial disclosures about commercial products (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018).” Nonetheless, it did not provide examples of which warnings and disclosures qualify as constitutional under this reasoning. In a subsequent federal case, several circuit court judges argued in their concurring opinion that only “health and safety warnings [that] date back to 1791” would qualify as “long considered permissible (ABA v. San Francisco 2019).” Thus, the government could not rely on the Supreme Court’s statement from NIFLA but rather would need to ensure its FOP labels qualified as accurate, factual, and uncontroversial to pass part two of the Zauderer test.

Lastly, Zauderer states that disclosures must not be “unjustified or unduly burdensome.” In order for a disclosure to be “justified,” the government must have evidence to support it (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018; Dwyer v. Cappell 2014). Therefore, the government must provide evidence that the problem it seeks to address is “real and not purely hypothetical (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018).” Importantly, rulings do not suggest that the government needs evidence that the disclosure would solve the issues identified; the Court has explained that “governments are entitled to attack problems piecemeal,” so a disclosure requirement need not solve “all facets of the problem it is designed to ameliorate (Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel 1985).” In addition, the disclosure cannot be unduly burdensome. The Court explained that a requirement is unduly burdensome when it would “chill” protected speech by dissuading it in the first place (Ibanez v. FL 1994). For example, the Court found the government violated this mandate in a case evaluating a Florida requirement that lawyers, who stated they were specialists on their business cards and letterhead, must include a disclaimer that was so detailed, it effectively ruled out their ability to use the designation (Ibanez v. FL 1994).

The First Amendment applies equally regardless of which level of government passes the labeling law. As such, the Zauderer standard has provided the basis for lower courts upholding other food labeling laws, such as calorie disclosures on restaurant menus (NYSRA v. NYC 2009) and country-of-origin (COOL) labeling on meats (AMI v. USDA 2014). (COOL labeling was upheld in the U.S. as consistent with the First Amendment despite international controversy over trade issues; Congress, in 2016, discontinued mandatory COOL for imported beef and pork products that are not yet packaged for consumer use.) In order to evaluate how theoretical FOP policies would fare under a First Amendment analysis in the U.S., we analyzed the international and U.S. FOP systems identified in our search described above under each of the three parts of the Zauderer test.

Two additional First Amendment tests were also relevant to our legal research. Courts have sometimes mistakenly applied the Central Hudson test to disclosure requirements even though this test is generally applicable to restrictions on commercial speech (AMI v. USDA 2014; RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012; Central Hudson v. Public Service Commission 1980). Under Central Hudson, courts ask whether the asserted governmental interest in restricting the speech is “substantial,” whether the regulation directly advances that interest, and whether it is not more extensive than necessary to serve that interest (Central Hudson v. Public Service Commission 1980). This test has proven more difficult to pass than Zauderer. The second test relevant to a disclosure requirement is the “strict scrutiny” test. Strict scrutiny applies when the government requires the disclosure of non-commercial fully protected speech (e.g., an ideological viewpoint) (Pacific Gas v. Public Utilities Commission 1986). If a court applies this test, it generally means the disclosure requirement will be found unconstitutional (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018). Courts thus strike down requirements that attempt to compel businesses to carry non-factual information in the commercial context (Entertainment Software Association v. Blagojevich 2006).

Therefore, the challenge for the government when mandating a FOP food label is to devise a FOP scheme that would be subject to and meet the Zauderer test. Thus, while we analyze the identified FOP policy options under Zauderer, we note relevant case law that applied Central Hudson or strict scrutiny when applicable.

Results

International and U.S. FOP Labels

A total of 30 FOP labels were identified and evaluated, including 24 used in other countries (16 voluntary, 8 mandatory) and six voluntary FOP labels used in the U.S. (Table 1; see Appendix for references). Identified FOP labels were classified into evaluative summary indicators (N=14), interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicators (N=8), nutrient-specific data (N=4), and hybrid systems (N=4). The evaluative summary indicators more often positively characterized products, while the interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicators utilized a mix of positive and negative information. Specifically, all fourteen evaluative summary indicators were voluntary; 11 used positive criteria and images (e.g., Swedish Keyhole); one, graded quality images (Hannaford Guiding Stars); and two, both positive and negative ratings (France and NuVal). Of the eight interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicators, three provided positive and negative interpretive information (e.g., Ecuador Traffic Light); three provided only negative interpretive information (e.g., Chile Excess Labels); one provided graded quality images (IOM); and one provided positive only (Singapore Healthier Choice Symbol). The four nutrient-specific data FOP labels (Mexico, Philippines, Thailand, and GMA/FMI’s Facts Up Front (FUF)) provided contents without characterizing the information as positive or negative (e.g., discloses specific information from the Nutrition Facts label on the FOP). Four hybrid systems included Australia/New Zealand’s Health Star Rating (mix of nutrient-specific data plus an evaluative summary indicator of graded quality), Slovenia’s Little Heart (a positive evaluative summary indicator and positive interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicator), and UK and Iranian Traffic Light systems (a mix of a nutrient specific data plus a nutrient specific summary indicator using both positive and negative information).

Table 1.

International and U.S.-based FOP Policies and Labeling Schemes

| Country or Entity/ Name of FOPS/foods |

Proposing Entity/Nutrition Disclosed | Nutrient-Specific Data; Interpretive Nutrient-Specific Summary Indicator; Evaluative Summary Indicator; Hybrid |

Image |

|---|---|---|---|

Australia and New Zealand Health Star Rating

|

|

Hybrid:

|

|

Belgium, Czech Republic, Netherlands, Poland, Nigeria, Slovakia: Choices Programme, Healthy Choice Logo

|

|

|

|

Brunei “Healthier Choice Symbol”

|

|

|

|

Chile Excess Warning Label

|

|

|

|

Ecuador Traffic Light Food Labeling System

|

|

|

|

Fiji / Solomon Islands

|

|

|

“This brand of canned luncheon meat/canned meat with (name of the other food) is high in fat. For a healthy diet eat less.” |

Finland Heart Symbol

|

|

|

(Better Choices) (Better Choices) |

Finland High Salt Content Warning

|

|

|

“High Salt Content” |

France NutriScore Label

|

|

|

|

Iran Traffic Light Label

|

|

Hybrid

|

|

Malaysia “Healthier Choice Logo”

|

|

|

|

Mexico Guideline daily amount labeling (GDA)

|

|

|

|

Nigeria Heart Check

|

|

|

|

Philippines “Wise Eat”

|

|

|

|

Philippines Energy logo

|

|

|

|

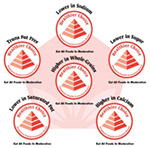

Singapore Healthier Choice Symbol

|

|

|

Singapore Health Promotion Board Eat all Foods in Moderation |

Slovenia “Little Heart” logo (formerly Protective Food symbol or Protects Health Label)

|

|

|

(Clear image with interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicator not available) |

South Korea Traffic Light Sign

|

|

|

|

Sri Lanka Traffic Lights

|

|

|

|

Swedish National Food Agency’s Keyhole Symbol

|

|

|

|

Thailand Guideline Daily Allowance

|

|

|

|

Thailand “Healthier Choice Logo”

|

|

|

|

United Arab Emirates Weqaya logo (“weqaya” means prevention in Arabic)

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom and EU Regulation Traffic Light label

|

|

Hybrid

|

|

United States American Heart Association Heart-Check Food Certification Program

|

|

|

|

United States Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) and Food Marketing Institute (FMI) Facts Up Front

|

|

|

|

United States Hannaford Guiding Stars

|

|

|

|

United States Institute of Medicine

|

|

|

|

United States

|

|

|

|

United States Walmart Great for you

|

|

|

|

Nearly all the FOP labels utilized a mixture of numbers (absolute numbers, percentages, scores), words, images, and colors to display nutritional information. Words typically characterized nutritional content (e.g., high sodium; trans-fat free) or expressed a qualitative evaluation of the food (e.g., Healthier Choice; Great for You), or identified the government or nongovernment entity providing the information (e.g., Singapore Health Promotion Board; Nuval). Images included checks, hearts, stars, pyramids, octagons, figures of people, and a keyhole. Certain colors were most common (e.g., red, blue) but did not consistently have any meaning; conversely, traffic light colors (red, amber, and green) were used to facilitate understanding of nutritional levels or quality (inferior, moderate, and superior). Only the Swedish Keyhole did not use any words or numbers. The foregoing findings for FOP labels implemented internationally and nationally provide potential policy options for U.S. consideration; the First Amendment analysis below applied the law to these policies.

First Amendment Application to Mandatory FOP Labels

The legal research uncovered case law evaluating First Amendment considerations for disclosure requirements in the commercial context. We report the results according to the three parts of the Zauderer test by separately applying the identified case law from each part of the test to the 30 identified FOP labels that served as theoretical policy options for the U.S.

Zauderer’s First Part: Reasonably Related to the State’s Interest

Previous cases provide insight into how courts interpret the requirement that disclosures must be reasonably related to the government's interest (Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel 1985). For example, the Second Circuit upheld Vermont’s requirement that manufacturers disclose the mercury content of their products on the products and packaging, based on the state’s interest in providing consumers with information to properly dispose of products to reduce contamination and protect environmental and human health (NEMA v. Sorrell 2001). The Second Circuit also upheld NYC’s requirement that restaurants disclose the number of calories per menu item on menus, based on both the interests in reducing consumer confusion and deception and in promoting informed consumer decision-making to reduce obesity and its comorbidities (NYSRA v. NYC 2009). The Ninth Circuit (which requires the government’s interest to be “substantial”) upheld Berkeley’s interests in protecting the health and safety of consumers, in the context of Berkeley’s requirement that cell phone retailers prominently display a notice at the point-of-sale disclosing federal guidelines for radio-frequency radiation exposure, even though federal law already required this information to be disclosed in cell phone manuals (CTIA v. Berkeley 2017). (The Supreme Court questioned this case but the Ninth Circuit stood by its decision (ABA v. San Francisco 2019).)

Conversely, when courts have found the government’s interest to be unconstitutional, they often were (mistakenly) applying Central Hudson to the disclosure requirement. Examples include the DC Circuit’s evaluation of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act’s (Tobacco Control Act) graphic warning labels for tobacco packaging, finding the government’s interest in “effectively” communicating health information regarding the negative effects of cigarettes was insufficient; however, it found sufficient, interests in encouraging current smokers to consider quitting and discouraging nonsmokers from initiating cigarette use (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). The Second Circuit found that “consumer curiosity” could not justify a factual disclosure requirement for milk products derived from rBST-treated cows (International Dairy v. Amestoy 1996). Similarly, the DC Circuit found an interest in “idle curiosity” likely insufficient to justify the federal COOL food labeling requirement. (However, it found other interest— questioned by legal scholars (Tushnet 2015; Post 2015) — to be sufficient: consumers wishing to buy American-made products, demonstrated consumer interest in countries of origin for foods, and individual health concerns and market impacts that can arise from food-borne illness outbreaks (AMI v. USDA 2014).)

Application of Zauderer’s First Part to International and U.S. FOP Labels

Regardless of the FOP policy the government chooses to pursue, legal precedent requires the government to set forth a valid interest to mandate a FOP label on food products. Like in NYC’s calorie labeling case, a valid interest would be to help prevent consumer confusion and deception for FOP labels that seek to clarify key nutritional information to assist consumers to identify healthier products especially in the face of various marketing messages on the front of packages and a potentially difficult to interpret Nutrition Facts label. Additional relevant interests upheld by other courts include promoting informed consumer decision-making (NRA v. NYC 2017) and protecting the health of consumers (CTIA v. Berkeley 2017).

Under the case law, the government’s interests in reducing consumer confusion and assisting consumers to make informed choices must be reasonably related to the disclosure requirement. Therefore, FOP labels that actually assist consumers to make informed choices, such as those that provide interpretive information, would be in line with this interest. Conversely, if a scheme’s significance or meaning is too attenuated or removed from the food products, such as the Swedish Keyhole, it might not be considered reasonably related to these interests. The Ninth Circuit case upholding Berkeley’s retail cell phone requirement would seem to provide a strong precedent for FOP labels because the court found the city’s interests in protecting the health and safety of consumers were “substantial,” even though the information was already required to be disclosed in the more detailed owner’s manual (CTIA v. Berkeley 2017), similar to the more detailed Nutrition Facts label for food. However, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of this remains unclear.

It is unclear whether a government interest in “effective” communication would be a sufficiently “valid interest,” despite its relevance to FOP labels, because the case striking it down under the Tobacco Control Act was decided under Central Hudson instead of Zauderer (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). Likewise, a government interest in encouraging food manufacturer reformulation would raise concerns under Central Hudson, but this is unclear under the Zauderer test. Under Central Hudson, the Court has disapproved of restricting speech to modify speakers’ behavior and instead suggested the government regulate the products directly, such as by limiting unhealthy ingredients or banning or restricting the sale of problematic products (Lorillard v. Reilly 2001). It can be argued that many if not most disclosure requirements seek to change consumer behavior (e.g., warning of toxic substances), even if they encourage reformulation. But, given that the protection of commercial speech is ostensibly to benefit consumers, the identified case law suggested that an interest in changing the speaker’s behavior may still be too attenuated under Zauderer.

Zauderer’s Second Part: Purely Factual, Accurate, and Uncontroversial Information about the Product or Service Itself

Most requirements that fail Zauderer, do so because courts find the disclosure was found to be not factual or uncontroversial under this second part of the test. Straightforward examples of factual information include Vermont’s mercury disclosure and NYC’s calorie labeling laws (NEMA v. Sorrell 2001; NYSRA v. NYC 2009). Likewise, the Sixth Circuit upheld the Tobacco Control Act’s textual health warnings (e.g., "WARNING: Cigarettes cause cancer"), finding the statements were factual and not disputed within the scientific or medical community (Discount Tobacco v. U.S. 2012). Similarly, a state court upheld NYC’s requirement that restaurants place a salt shaker image and warning statement next to menu items that contain more sodium than the federal daily recommended limit, stating that scientific evidence “is factual, accurate and uncontroversial” that consuming a day’s worth of sodium can increase medical risks (NRA v. NYC 2017).

Conversely, in NIFLA, the Court found that Zauderer did not apply to a state requirement that licensed reproductive health facilities disclose information about the availability of state services because the disclosure did not relate to the services the regulated entities provided including “abortion, anything but an ‘uncontroversial’ topic (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018).” Prior to this case, appellate courts traditionally explained “controversial” to mean that the factual basis was controversial, not that there is controversy surrounding the topic (Pomeranz 2015). For example, GMO labeling is politically controversial but whether a product is genetically modified is not (GMA v. Sorrell 2015). NIFLA may provide cause for concern because it would be difficult to find a public health topic that is not controversial (Berman 2016). At the same time, it is unclear the extent the Court’s statement is related to the first finding— that the disclosure was not about the services provided— or whether a factual disclosure would be subject to strict scrutiny instead of Zauderer if the subject matter itself is controversial (Pomeranz 2019).

Additional cases failing this part of Zauderer include a federal requirement that certain securities issuers disclose the use of “conflict minerals,” referring to the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The DC Circuit found that this was not “factual and non-ideological” because it required the issuer “to tell consumers that its products are ethically tainted (NAM v. SEC 2015).” The court found that the government’s factual definition of “conflict free” did not cure the defect and cautioned that otherwise, “there would be no end to the government's ability to skew public debate by forcing companies to use the government's preferred language” of “moral responsibility,” such as stating products were “not ‘environmentally sustainable’ or ‘fair trade’ … even if the companies vehemently disagreed that their products were ‘unsustainable’ or ‘unfair (NAM v. SEC 2015).’”

Lastly, the DC Circuit found the FDA’s proposed graphic tobacco warning labels unconstitutional, stating “the images do not convey any warning information” or “accurate” statements about cigarettes (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). The FDA provided evidence that “pictures are easier to remember than words” and explained that they were “not meant to be interpreted literally,” but rather to symbolize the textual warning statements (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). However, the court found that the labels unconstitutionally required tobacco products to be a “‘mini billboard’ for the government's anti-smoking message” and that images, such as of a woman crying and a small child, did not provide information about the health effects of smoking and were subject to misinterpretation by consumers (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). In addition, the majority deemed the government’s "1-800-QUIT-NOW" hotline, biased and “provocatively-named.” The dissent, which would have upheld the graphic warnings under Zauderer, likewise found that the hotline would fail both Zauderer and Central Hudson (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012).

Application of Zauderer’s Second Part to International and U.S. FOP Labels

According to the second requirement under Zauderer, the FOP label itself and the underlying nutrition definition must be accurate, factual, and uncontroversial, and about the food products themselves (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018). The identified case law suggested that nutrient-specific data disclosures, such as Thailand’s and the GMA/FMI’s FUF, should meet the requirement to be accurate, factual, and uncontroversial because they provide raw data and convey the government’s recommended percent daily value targets for the information disclosed. FOP labels that provide information and simultaneously disclose the basis for their symbols on the food packages themselves may avoid being considered subject to misinterpretation and may also meet Zauderer. For example, the Australian/New Zealand scheme is a hybrid disclosure of factual nutrition information and a summary indicator using stars based on information disclosed on the NFP and ingredient list. Thus, the star provides a summary evaluation of factual criteria disclosed elsewhere on the package. Similarly, the IOM’s proposed FOP label is based entirely on nutrients disclosed on the NFP; using symbols, it interprets and integrates the NFP itself.

The substance of Chile’s Excess Warning Labels for high sugar and salt would also seem to fit the second requirement under Zauderer because it warns about ingredients that can harm when consumed in excess. Legal precedent indicated that the underlying standard should be clearly explained scientifically (Pearson v. Shalala 1999), perhaps similar to New York City’s sodium warning in that there can be no question that the product is one of concern (NRA v. NYC 2017). However, the food industry could challenge Chile’s labels based on an argument that the design— the black octagon shape (implying a “stop sign” or warning)— is controversial. On one hand, warnings about products (e.g., tobacco warnings) are clearly constitutional (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018) and the stop sign symbolizes the same concept but using a visual image to assist consumer understanding. On the other hand, the industry might argue that the stop sign is a controversial method to warn about ingredients of concern and could be interpreted to indicate concern over the entire product rather than just the ingredients of concern– which from a public health perspective may be considered accurate but from an industry perspective would be considered controversial. It is unknown if a court would agree that the design is controversial. Potential methods to provide scientifically valid information similar to Chile’s FOP label (and NYC’s sodium warning icon), but potentially less controversially, could be for the FOP to warn of high sugar or salt using words, such as Finland’s “High Salt Content,” or enclosing the message using a less “provocative” shape (e.g., a rectangle), or using an image of salt (or sugar) as upheld in the NYC sodium warning menu labeling case.

The traffic light system provides factual nutrition information similar to FUF but with colors to assist consumers interpret the information as opposed to the monochrome FUF which may be more difficult to interpret. If the colors matched nutrition standards otherwise used for food labeling, for example if they correspond with the Nutrition Facts label’s Percent Daily Values and RDIs like FUF, this would align with Zauderer’s requirement to be factual and accurate. Yet, it is unclear whether the traffic light colors themselves would qualify as controversial under the First Amendment given red’s connotation to stop. However, even more so than Chile’s excess warning, the colors clearly relate to ingredients of concern and not the entire product. Therefore, there is a good argument that the colors should be regarded as uncontroversial because they assist in consumer interpretation of the facts already disclosed on the package (which also supports the government’s interest in requiring them).

The case law suggested that it might prove challenging under the First Amendment for the government to require evaluative summary indicators that do not disclose factual information but rather solely use graphics such as stars, hearts, and check marks. When the DC Circuit struck down the FDA’s graphic warning labels, it found that the images did not convey warning information or make an accurate statement about cigarettes (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). Applying this reasoning to FOP labels, the label should provide factual and accurate information, not a symbol alone, about the product’s nutrition content so it is not subject to misinterpretation (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012). For example, the Swedish Keyhole does not meet this standard and conveys no factual information on its own. Similarly, Finland’s “Better Choice” might be subject to misinterpretation (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012)– better than what, or for what, or for whom?- or even ideological (NAM v. SEC 2015): a “mini-billboard” for the government’s “eat healthy” message. Similarly, a generic FOP that suggested consumers “eat healthy” would additionally fail Zauderer because it would not be about the food product itself (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018). Legal precedent suggested that courts would likely find the foregoing even if they are based on factual nutrition science, because factual definitions have not previously cured non-factual disclosure requirements (NAM v. SEC 2015).

Zauderer’s Third Part: Not Unjustified or Unduly Burdensome

As noted, a disclosure requirement may not be “unjustified or unduly burdensome.” Therefore, the government must justify its requirement with evidence supporting the requirement itself, as courts regularly review the evidence in the government’s record (RJ Reynolds v. FDA 2012; Discount Tobacco v. U.S. 2012; NAM v. SEC 2015). Related to the prohibition on unduly burdensome disclosure requirements, in NIFLA, the Court found burdensome a state’s requirement that unlicensed clinics disclose a notice in all print and digital advertising using text that is larger and in contrasting type or color to the main message, and in as many as 13 different languages (NIFLA v. Becerra 2018). Similarly, the Ninth Circuit found San Francisco’s requirement that the SSB warning must occupy 20% of the advertisement, to be overly burdensome (ABA v. San Francisco 2019), and a lower court found a disclaimer burdensome when the font size was required to be at least as large as the largest print size used in the advertisement (Public Citizen v. LA 2011). Conversely, the Sixth Circuit upheld the Tobacco Control Act’s requirement that tobacco warnings must take up 50% of the front and back of cigarette packages (Discount Tobacco v. U.S. 2012), and courts upheld a disclosure that was required to be in all caps (or a similarly distinguishable manner) (Borgner v. Brooks 2002), and one that required the font size to be the same or larger than the font size of the statement it was meant to clarify (Loan Payment v. Hubanks 2015).

Application of Zauderer’s Third Part to International and U.S. FOP Labels

To satisfy the requirement under Zauderer that the FOP label must be justified, the government must amass evidence on the need for the FOP system it chooses as well as the scientific basis to support the disclosure itself. Evidence is thus necessary to support the nutrition rationale for the FOP scheme and to clarify the government’s bases for policymaking, which include the interests identified above: addressing consumer confusion and deception and enabling consumers to make informed choices about the foods they purchase and consume.

In order to avoid being burdensome, the identified case law suggested that the government must limit the size of the FOP symbol and should not require the FOP label to be displayed in more than one language. An indication that the size of the current FOP labels are not burdensome is the routine voluntary use by food companies; for example, FUF is utilized in the U.S. and internationally by over 90 companies (Food Industry Asia 2016; GMA/FMI). Despite the Sixth Circuit upholding the constitutionality of the requirement that tobacco manufacturers reserve 50% of both sides of cigarette packaging for health warnings (Discount Tobacco v. U.S. 2012), a similar finding is unlikely for food. The Ninth Circuit found that San Francisco’s sugary beverage advertisement warnings were too large even though they were the same size as warnings required to be placed on tobacco product advertisements (ABA v. San Francisco 2019). Moreover, unlike cigarette packages, the principal display panel on food packages is a primary mode that manufacturers use to communicate commercial information about their products to consumers. Food companies could argue that a 50% requirement amounts to an unconstitutional restriction on commercial speech, with which a court could agree under Central Hudson (Berman 2016). Current FOP labels and symbols take up a relatively small amount of space. For example, Chile’s mandatory FOP symbols are required to be approximately 4-10% of the FOP surface depending on the package size (USDA 2015). Thus, a requirement closer to the actual size commonly used would be less constitutionally questionable.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Despite the effectiveness of labeling interventions (Shangguan et al. 2019) and the global interest in FOP schemes (Kanter et al. 2018), there has been no federally mandated adoption in the U.S. Therefore, First Amendment evaluation of FOP policy options is essential to understand its potential as a viable policy option in the U.S. This investigation identified 30 existing FOP labels utilized internationally and nationally that varied in format, information disseminated, intent, and the level of positive or negative information conveyed. Some FOP labels disclose data using numbers or words, whereas others are more interpretive or evaluative. While the U.S. government could create a voluntary FOP icon without implicating the First Amendment, our analysis demonstrates that a mandatory FOP label is possible if implemented consistent with established legal precedent. This includes ensuring that disclosures would further valid government justifications of addressing consumer confusion and providing information to enable healthy choices; are factual, accurate and about the products themselves; relatively modest in size while remaining clearly visible and noticeable; in one language; and based on scientific evidence. In particular, FOP labels which disclosed nutrient-specific data would likely meet First Amendment requirements as purely factual and uncontroversial and reasonably related to the identified government interests. Interpretive nutrient-specific summary information which provides factual information with colors or designs to assist consumers interpret the information should similarly withstand First Amendment scrutiny, but questions remain regarding whether certain colors or shapes would qualify as controversial. Evaluative summary indicators that provide no information and only an image to characterize the entire product (e.g., check marks) may be more difficult to mandate in the U.S. because they do not provide factual information. Many identified evaluative summary indicators provided positive information only so given strong market incentives to disclose favorable qualities, manufacturers would likely continue to utilize these positive FOP labels voluntarily (Caswell, Mojduszka 1996).

Traffic light FOP icons present an interesting case because on one hand the scientific literature indicates that consumers notice and can use them better than other schemes, particularly monochrome FOP labels (Balcombe et al. 2010; Roberto et al. 2012; Hawley et al. 2013; Becker et al. 2015), and thus, they are clearly reasonably related to the government’s goals and there is evidence to support them, meeting the Zauderer test. On the other hand, the colors have latent meaning to which the industry might object. However, if the colors correspond with information already disclosed on the Nutrition Facts label, then providing interpretive help to consumers should not actually be considered controversial. Nonetheless, if a court were to find the actual traffic light colors (red, amber, green) were controversial, the government could revise the color scheme and educate the public on the meaning of the chosen colors. This would be a method to provide factual information and assist consumers of all backgrounds. Given that the FOP label should be in only one language, interpretive colors are helpful for non-English speakers, youth, and those who have difficulty reading. Similarly, schemes that provide information and simultaneously disclose the basis for their symbols on the food packages using symbols, like the Australian and IOM’s recommended FOP label, should meet the Zauderer test and may help consumers of all literacy levels identify healthier products.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate international and U.S.-based FOP systems and analyze the legal feasibility of the U.S. government mandating such a FOP label consistent with the First Amendment. These findings have important implications for any federal government efforts to mandate a FOP label. The government can dedicate scarce resources to developing the evidence base for FOP labels more likely to withstand First Amendment scrutiny. Whichever FOP label the government were to choose, such a system should be tested for efficacy and salience among consumers.

This study has potential limitations. We may not have captured all the FOP labels in use internationally or nationally. Further, First Amendment jurisprudence in this area is in a state of extreme flux so courts could disagree with the analysis presented. In addition, new and emerging cases continuously provide new insights on the constitutionality of disclosure requirements and it will take years to understand how the nuances of these decisions affect commercial disclosure requirements. Additionally, the most legally viable FOP label might not be the most salient or effective for consumers. Finally, we did not evaluate which FOP schemes would be most applicable for voluntary adoption, nor did we examine international legal issues or world trade issues related to FOP labels. The foregoing limitations are all viable areas for future research and analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

A diverse range of FOP labels have been implemented globally, including mandatory and voluntary systems outside of the U.S. and voluntary systems within the U.S. Specific legal considerations in the U.S., particularly related to the First Amendment, provide important information about which types and characteristics of FOP labels would be most legally feasible to require. Our findings suggest that any mandatory government FOP scheme should carefully align its requirement with First Amendment jurisprudence to avoid a successful legal challenge.

Highlights.

Front-of-package (FOP) food labels are increasingly being considered in the US

FOP labels may support healthier food choices and encourage reformulation

Systematic comparison of global FOP labels adds a range of U.S. policy options

In the U.S., mandatory FOP labels must be consistent with the First Amendment

Certain FOP labels could face legal obstacles if mandated in the U.S.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all of the collaborators and advisory groups in the Food Policy Review and Intervention Cost-Effectiveness (Food-PRICE) project (www.food-price.org). The authors wish to thank Nicole Gracias, Gabriella Bolanos, and Joshua Arshonsky for their stellar research assistance.

Funding

This research was supported by the NIH, NHLBI (R01 HL130735). The funding agencies did not contribute to design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

All authors report support from NIH grants during the conduct of the study. In addition, Dr. Micha reports research funding from Unilever and personal fees from the World Bank and Bunge; and Dr. Mozaffarian, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Acasti Pharma, GOED, DSM, Haas Avocado Board, Nutrition Impact, Pollock Communications, Boston Heart Diagnostics, Bunge, and UpToDate; all outside the submitted work.

Appendix

International and U.S.-based FOP References a

| Country or Entity/ Name of FOPS/foods |

Image | |

|---|---|---|

| Australia and New Zealand Health Star Rating | Australian Government Department of Health. Health Star Rating System. December 23, 2016. http://healthstarrating.gov.au/internet/healthstarrating/publishing.nsf/Content/About-health-stars. (accessed August 8, 2017). | |

| Belgium, Czech Republic, Netherlands, Poland, Nigeria, Slovakia: Choices Programme, Healthy Choice Logo | Choices Programme https://www.choicesprogramme.org (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| Brunei “Healthier Choice Symbol” | Brunei “Healthier Choice Symbol” http://www.moh.gov.bn/Image%20Gallery/HealthyChoiceLogo/Nutrient%20Criteria%20of%20Foods%20and%20Beverages%20with%20the%20Healthier%20Choice%20Logo.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| Chile Excess Warning Label | Rodriguez Osiac L. The implementation of new regulations on nutritional labelling in Chile. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tbt_e/8_Chile_e.pdf. (accessed September 6, 2017). |

|

| Ecuador Traffic Light Food Labeling System | Salameh B. Food labeling in Ecuador: Will the power of the people triumph over the power of the food industry. Groundswell International. November 3, 2016. https://www.groundswellinternational.org/ecuador/food-labeling-in-ecuador-will-the-power-of-people-triumph-over-the-power-of-the-food-industry/. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| Fiji / Solomon Islands | WCRF. NOURISHING Database. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database (accessed July 13, 2018). |

“This brand of canned luncheon meat/canned meat with (name of the other food) is high in fat. For a healthy diet eat less.” |

| Finland Heart Symbol | Sydanliitto. Heart Symbol. http://www.sydanmerkki.fi/en/criteria-for-healthy-lunch. (accessed August 10, 2017). |

(Better Choices) (Better Choices) |

| Finland High Salt Content Warning | Finland. High Salt Content Warning Labels. March 2009. http://www.worldactiononsalt.com/worldaction/europe/53774.html. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

“High Salt Content” |

| France NutriScore Label | http://www.euro.who.int/en/countries/france/news/news/2017/03/france-becomes-one-of-the-first-countries-in-region-to-recommend-colour-coded-front-of-pack-nutrition-labelling-system (accessed July 13, 2018). |  |

| Iran Traffic Light Label | WCRF. NOURISHING Database. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| Malaysia “Healthier Choice Logo” | WCRF. NOURISING Database https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database?topic=Front-of-pack (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| Mexico Guideline daily amount labeling (GDA) | WCRF. NOURISHING Database. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| Nigeria Heart Check | Nigeria. Nigeria Heart Check Logo. http://www.nigerianheart.org/ApprovedProducts.html. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| Philippines “Wise Eat” | Philippines. “Wise Eat” http://ilsisea-region.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2016/06/Session-3-2_Pauline-Chan.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| Philippines Energy logo | Philippines Energy logo http://ilsisea-region.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2016/06/Session-3-2_Pauline-Chan.pdf (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| Singapore Healthier Choice Symbol | Singapore. The Healthier Choice Symbol (HCS). May 6, 2016. https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/913/reading-food-labels. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

Singapore Health Promotion Board Eat all Foods in Moderation |

| Slovenia “Little Heart” logo | Slovenia “Little Heart” logob http://zasrce.si/znak_varovalna_zivila/ https://www.aktivni.si/prehrana/oznake-za-prvake/ (accessed July 13, 2018) |

(Clear image with interpretive nutrient-specific summary indicator not available) |

| South Korea Traffic Light Sign | South Korea. Traffic light color nutrition label. August 4, 2013. http://www.icfood.co.kr/_module/bbs/view.html?module=join&bo_id=notice_news&pmmu=3&smmu=3&idx=940. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| Sri Lanka Traffic Lights | Sri Lanka. Traffic Lights. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database?country=Sri%20Lanka (accessed July 13, 2018) |

|

| Swedish National Food Agency’s Keyhole Symbol • Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland |

Sweden. The National Food Agency’s Keyhold Symbol. February 24, 2015. https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/en/food-and-content/labelling/nyckelhalet. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| Thailand Guideline Daily Allowance • FOP • Snack foods • Mandatory |

Thailand. Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA). June 13, 2011. https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Thai%20FDA’s%20New%20Guideline%20Daily%20Amounts%20(GDA)%20Labeling%20_Bangkok_Thailand_6-13-2011.pdf. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| Thailand “Healthier Choice Logo” | Thailand “Healthier Choice Logo” https://www.choicesprogramme.org/news-updates/news/thailand-launches-healthier-choico-logo-to-reduce-ncds/ (accessed July 13, 2018). |

|

| United Arab Emirates Weqaya logo (“weqaya” means prevention in Arabic) | WCRF. NOURISHING Database. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database (accessed July 13, 2013). |

|

| United Kingdom and EU Regulation Traffic Light label | U.K. Department of Health &Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. Food Labeling e-Learning Course, Additional forms of expression (AFE). Food Standards Agency. http://labellingtraining.food.gov.uk/module5/overview_5.html. (accessed August 9, 2017). |

|

| United States American Heart Association Heart-Check Food Certification Program | American Heart Association. The Heart-Check Mark. June 27, 2016. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyEating/Heart-CheckMarkCertification/How-the-Heart-Check-Food-Certification-Program-Works_UCM_300133_Article.jsp#.WY0W8NPyuu5. (accessed August 10, 2017). |

|

| United States Grocery Manufacturers Association (GMA) and Food Marketing Institute (FMI) Facts Up Front | GMA/FMI Facts Up Front. http://www.factsupfront.org/AboutTheIcons. (accessed September 30, 2017). |

|

| United States Hannaford Guiding Stars | Hannaford. Guiding Stars. https://guidingstars.com/what-is-guiding-stars/. (accessed August 8, 2017). |

|

| United States Institute of Medicine | Institute of Medicine. 2012. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Promoting Healthier Choices. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.ors/10.17226/13221. Chapter 7. https://www.nap.edu/read/13221/chapter/9#75 |

|

| United States NuVal Nutritional Scoring System | Katz, D. NuVal System. NuVal LLC. http://www4.nuval.com/How. (accessed August 8, 2017). |

|

| United States Walmart Great for you | Walmart. The Great For You Icon. 2017. http://corporate.walmart.com/global-responsibility/hunger-nutrition/great-for-you. (accessed August 10, 2017). |

|

The WCFR NOURISHING Database was consulted for all international FOP labels even when not specified.

Additionally, author personal email communication with Društvo za zdravje srca in ožilja Slovenije, Slovenian Heart Foundation (July 2018).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Am. Bev. Ass'n (ABA) v. City & County of San Francisco, 2019 U.S. App. LEXIS 3175 (9th Cir. 2019).

- Adler JH. Compelled Commercial Speech and the Consumer “Right to Know.” 58 Ariz. L. Rev. 421 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed A, Richtel M, Jacobs A. In Nafta Talks, U.S. Tries to Limit Junk Food Warning Labels. The New York Times; March 20, 2018https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/20/world/americas/nafta-food-labels-obesity.html [Google Scholar]

- Am. Meat Inst. v. (AMI) United States Dep't of Agric., 760 F.3d 18 (2014).

- Andrews JC, Burton S, Kees J. Is Simpler Always Better? Consumer Evaluations of Front-of-Package Nutrition Symbols. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing: 2011;30(2):175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Balcombe K, Fraser I, Di Falco S. Traffic lights and food choice: A choice experiment examining the relationship between nutritional food labels and price. Food Policy 2010;35:211–220 [Google Scholar]

- Becker MW, Bello NM, Sundara RP, Peltiera C, Bixa L. Front of pack labels enhance attention to nutrition information in novel and commercial brands. Food Policy. 2015;56:76–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman ML. Clarifying Standards for Compelled Commercial Speech, 50 Wash. U. J.L. & Pol'y 53 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Bialkova S, Grunert KG, van Trijp H. Standing out in the crowd: The effect of information clutter on consumer attention for front-of-pack nutrition labels. Food Policy 2013;41:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Board O. Competition and Disclosure. The Journal of Industrial Economics 2009;57(1). [Google Scholar]

- Board of Trustees of State Univ. of N.Y. v. Fox, 492 U.S. 469 (1989).

- Borgner v. Brooks, 284 F.3d 1204 (11th Cir. 2002).

- Caswell JA, Mojduszka EM. Using Informational Labeling to Influence the Market for Quality in Food Products. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 1996;78(5):1248–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Cent. Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Public Serv. Comm'n, 447 U.S. 557 (1980).

- CTIA - Wireless Ass'n v. City of Berkeley, 854 F.3d 1105 (9th Cir. 2017).

- Discount Tobacco City & Lottery, Inc. v. U.S., 674 F.3d 509 (6th Cir. 2012)

- Draper AK, Adamson AJ, Clegg S, Malam S, Rigg M, Duncan S Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: are multiple formats a problem for consumers? Eur J Public Health 2013;23(3):517–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: are multiple formats a problem for consumers? Eur J Public Health 2013;23(3):517–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer v. Cappell, 762 F.3d 275 (3rd Cir. 2014).

- Entertainment Software Association v. Blagojevich, 469 F.3d 641 (7th Cir. 2006).

- Federal Register. August 22, 2018;83(163):42513–42514. [Google Scholar]

- Food Industry Asia. FAST FACTS ON PACKS GDA Nutrition Labelling Report 2016. https://foodindustry.asia/documentdownload.axd?documentresourceid=21221

- Golan E, Kuchler F, Mitchell L, Greene C and Jessup A, 2001. Economics of food labeling. Journal of Consumer Policy 2001;24(2):117–184. [Google Scholar]

- GMA/FMI Facts Up Front. http://www.factsupfront.org/AboutTheIcons.

- Grocery Mfrs. Ass’n v. Sorrell, 102 F. Supp. 3d 583 (D.Vt. 2015).

- Hawley KL, Roberto CA, Bragg MA, Liu PJ, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. The science on front-of-package food labels. Public Health Nutr 2013;16(3):430–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieke S, Harris JL. Nutrition information and front-of-pack labelling: issues in effectiveness. Public Health Nutrition 2016;19(12), 2103–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotz VJ, Xiao M. Strategic Information Disclosure: The Case Of Multiattribute Products With Heterogeneous Consumers. Economic Inquiry, Western Economic Association International 2013;51(1):865–881. [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez v. Fla. Dep't of Bus. & Prof'l Regulation, 512 U.S. 136 (1994).

- International Dairy Foods Association v. Amestoy, 92 F.3d 67 (2nd Cir. 1996).

- Institute of Medicine. 2010. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Phase I Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/12957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Promoting Healthier Choices. October 20, 2011. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Front-of-Package-Nutrition-Rating-Systems-and-Symbols-Promoting-Healthier-Choices.aspx.

- Institute of Medicine. 2012. Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols: Promoting Healthier Choices. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/13221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter R, Vanderlee L, Vandevijvere S. Front-of-package nutrition labelling policy: global progress and future directions. Public Health Nutr 2018;21(8):1399–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Abbé MR, McHenry EW, Emrich T. What is Front-of-Pack Labelling? Codex Committee on Food Labelling FAO/WHO Information Meeting on Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling Charlottetown PEI, May 11, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein AH. IOM Report on Front-of-Package Nutrition Rating Systems and Symbols 2013. http://www.who.int/nutrition/events/2013_FAO_WHO_workshop_frontofpack_nutritionlabelling_presentation_Lichtenstein.pdf [PubMed]

- Loan Payment Admin, LLC v. Hubanks, 2015 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 32897 (N.D.Cal., March 17, 2015).

- Loewenstein G, Sunstein CR, Golman R. Disclosure: Psychology Changes Everything. Annu. Rev. Econ 2014. 6:391–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lorillardv. Reilly, 533 U.S. 525 (2001).

- Micha R, Peñalvo JL, Cudhea F, Imamura F, Rehm CD, Mozaffarian D Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017;317(9):912–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milavetz, Gallop &Milavetz, P.A. v. U.S., 559 U.S. 229 (2010).

- Nat'l Ass'n of Mfrs. (NAM) v. SEC, 800 F.3d 518 (D.C. Cir. 2015).

- Neal B, Crino M, Dunford E, Gao A, Greenland R, Li N, Ngai J, Ni Mhurchu C, Pettigrew S, Sacks G, Webster J, Wu JH. Effects of Different Types of Front-of-Pack Labelling Information on the Healthiness of Food Purchases-A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2017;9(12). pii: E1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nat'l Elec. Mfrs. Ass'n (NEMA) v. Sorrell, 272 F.3d 104 (2nd Cir. 2001).

- Nestle M Chile’s new food labeling rules: Why can’t we do this? Food Politics. December 19, 2013. https://www.foodpolitics.com/2013/12/chiles-new-food-labeling-rules-why-cant-we-do-this/

- Nat'l Inst. of Family & Life Advocates (NIFLA) v. Becerra, 2018 U.S. LEXIS 4025 (June 26,2018)

- The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA), Public Law 101-535 (1990).

- New York State Restaurant Association (NYSRA) v. NYC Board of Health, 556 F.3d 114 (2nd Cir. 2009).

- National Restaurant Association (NRA) v. NYC Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, 148 A.D.3d 169 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. App Div. 1st Dept 2017).

- Pac. Gas & Elec. Co. v. Pub. Utilities Comm'n of Cal., 475 U.S. 1, 16 (1986).

- Pearson v. Shalala, 164 F.3d 650 (D.C. Cir. 1999).

- Phulkerd S, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, Worsley A, Lawrence M. Barriers and potential facilitators to the implementation of government policies on front-of-pack food labeling and restriction of unhealthy food advertising in Thailand. Food Policy 2017;71:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz JL Outstanding Questions In First Amendment Law Related To Food Labeling Disclosure Requirements For Health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1986–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz JL. Abortion Disclosure Laws and the First Amendment: The Broader Public Health Implications of the Supreme Court's Becerra Decision. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):412–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RC Edwin Baker Lecture for Liberty, Equality, and Democracy: Compelled Commercial Speech. 117 W. Va. L. Rev. 867 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Public Citizen v. La. Atty. Disciplinary Bd, 632 F.3d 212 (5th Cir. 2011).

- Rahkovsky I, Lin B-H, Lin C-TJ, Lee J-Y. Effects of the Guiding Stars Program on purchases of ready-to-eat cereals with different nutritional attributes: Research article. Food Policy 2013;43:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm CD, Peñalvo JL, Afshin A, Mozaffarian D Dietary Intake Among US Adults, 1999-2012. JAMA 2016;315(23):2542–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. FDA, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012).

- Roberto CA, Bragg MA, Schwartz MB, Seamans MJ, Musicus A, Novak N, Brownell KD. Facts up front versus traffic light food labels: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43(2):134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin v. Coors Brewing, 514 U.S. 476 (1995).

- City and County of San Francisco (San Francisco Ordinance). Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Warning for Advertisements. Ordinance No.100-15 (June/25/15).

- Shangguan S, Afshin A, Shulkin M, Ma W, Marsden D, Smith J, Saheb-Kashaf M, Shi P, Micha R, Imamura F, Mozaffarian D; Food PRICE (Policy Review and Intervention Cost-Effectiveness) Project. A Meta-Analysis of Food Labeling Effects on Consumer Diet Behaviors and Industry Practices. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(2):300–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talati Z, Pettigrew S, Dixon H, Neal B, Ball K, Hughes C. Do Health Claims and Front-of-Pack Labels Lead to a Positivity Bias in Unhealthy Foods? Nutrients 2016;8:787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tushnet R COOL Story: Country of Origin Labeling and the First Amendment, 70 Food Drug L.J. 25 (2015). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA. Chile Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards. Gain Report No. CI1527. 11/September/2015. http://agriexchange.apeda.gov.in/IR_Standards/Import_Regulation/Food%20and%20Agricultural%20Import%20Regulations%20and%20Standards%20%20NarrativeSantiagoChile1192015.pdf.

- World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF). NOURISHING Framework Database. https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database

- Whole Grains Council. Whole Grain Stamp. https://wholegrainscouncil.org/whole-grain-stamp

- Wilde P Food Policy in the United States: An Introduction (2nd Edition). 2018. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court, 471 U.S. 626 (1985).