1. Introduction

In the past two decades, we have witnessed significant advances in the management of autoimmune diseases. The widespread use of biologic therapies in patients with severe or refractory autoimmune diseases has improved the prognosis of these conditions. Tocilizumab (TCZ), an anti-interleukin 6 receptor (IL-6 R), is one of these biologic agents. Recent studies indicate that TCZ is an effective treatment in SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) patients [1,2]. In the present report, we briefly summarized the use of TCZ in rheumatic diseases as well as the recent evidence supporting its use in the treatment for COVID-19 patients experiencing severe complications.

This editorial was elaborated by a group of clinicians that included two rheumatologists with experience in the management of systemic diseases, an internist dedicated to vasculitis and autoinflammatory syndromes, a pneumologist, and an infectious diseases specialist. Based on our vision as clinical physicians involved in different aspects of COVID-19, we have realized that human beings often learn from our own mistakes. Unfortunately, we do not tend to learn from others in advance for taking early actions against any new potential threat when this danger signal is affecting other communities or countries may be too far from us (but not any longer in today’s globalized world). In addition, when COVID-19 arrives in our own countries, mainly infectious diseases and intensive care specialists rapidly take over the management of the acute process with all the weapons available at this time (again, being unaware of all the medical information from other affected countries in this regard). Several days or weeks later, most physicians dedicated to immunology and autoimmune diseases discover that the disease is of our concern, due to the predominant immunology-mediated hyperinflammatory response as the ultimate cause of death in COVID-19 patients. A delayed implication is also recognized by hematologists for problems derived from a hypercoagulative state, and pulmonologists for the acute and chronic consequences of the early and uncontrolled lung involvement. This is a repetitive process that has sadly occurred (and still occurs) in all the places in a similar way. However, we finally learn that working together altruistically as a local or international network, and also bringing together expert people from different fields in multidisciplinary teams, can make us succeed and defeat this infectious and immune-inflammatory pandemic disease caused by a complex virus.

2. The role of tocilizumab in systemic autoimmune and inflammatory diseases

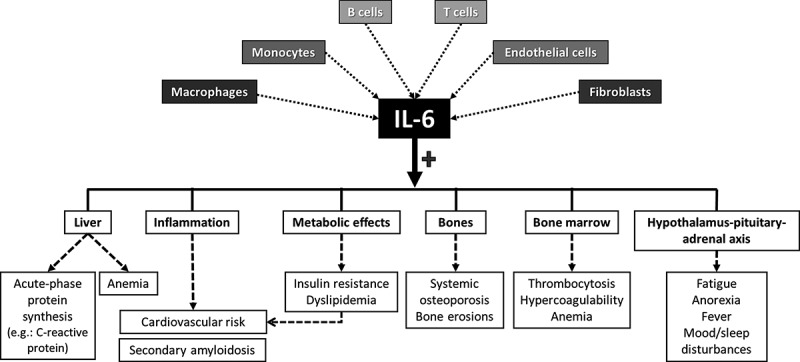

Going back to inflammation, it is already known that interleukin 6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine, which, apart from its role in the inflammatory and immune responses, influences a variety of systems (Figure 1). This pivotal proinflammatory cytokine promotes the production of acute-phase protein such as the C-reactive protein (CRP) by the liver. IL-6 also leads to the hepatic production of hepcidin that is responsible for the development of chronic anemia in inflammatory conditions. The effect of IL-6 on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis promotes the development of fatigue. Besides effects on osteoporosis, IL-6 induces metabolic abnormalities that lead to insulin resistance, and it is also implicated in the increased risk of cardiovascular disease associated with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases [3].

Figure 1.

Pleiotropic effects of interleukin-6 (IL-6).

TCZ is the first recombinant humanized anti-human monoclonal antibody directed against soluble and membrane-bound interleukin 6 receptors (IL-6 R). TCZ inhibits the binding of IL-6 to its receptors, thus reducing this cytokine’s pro-inflammatory activity by competing with both the soluble and membrane-bound forms of the IL-6 R [4]. This biologic agent prevents the interaction of IL-6 with both the IL-6 R and the signal transducer glycoprotein 130 complex, which leads to inhibition of both the cis- and trans-signaling cascades involving the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and the activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway [5].

As illustrated in Table 1, the anti-IL-6 R tocilizumab has been labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for different autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), giant cell arteritis (GCA), and severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS) secondary to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy. Of note, CRS is directly caused by the excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines during an exaggerated immune response [6].

Table 1.

Current indications of tocilizumab.

| Autoimmune/ inflammatory condition | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | FDA administration route | European Medicines Agency (EMA) | EMA administration route |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | Adults with active RA and inadequate response to DMARDs | IV or SC | Adults with severe RA and inadequate response to methotrexate, or with moderate to severe active RA not responding to DMARDs or TNF blockers |

IV or SC |

| Systemic JIA | Patients ≥ 2 years with active disease | IV | Patients ≥ 1 year with poor response to NSAIDs and GC | IV |

| Polyarticular JIA | Patients ≥ 2 years with active disease | IV | Patients ≥ 2 years with active disease, not responding to methotrexate | IV or SC |

| GCA | Adult patients | SC | Adult patients | SC |

| CRS due to CAR-T cell therapy | Adults and pediatric patients ≥2 years with CAR T cell-induced severe or life-threatening CRS |

IV | Adults and pediatric patients ≥2 years with CAR T cell-induced severe or life-threatening CRS |

IV |

Abbreviations: CAR = Chimeric antigen receptor; CRS = Cytokine release syndrome; DMARDs = Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; GC = Glucocorticoids; GCA = Giant cell arteritis; IV = Intravenous; JIA = Juvenile idiopathic arthritis; NSAIDs = Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RA = Rheumatoid arthritis; SC = Subcutaneous; TNF = Tumor necrosis factor.

In more detail, TCZ was initially approved for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors [7], and systemic onset JIA, at doses of 4–8 mg/kg intravenously once every 2 weeks [8]. More recently, a clinical trial in patients with GCA, the most common systemic vasculitis in people older than 50 years, using subcutaneous TCZ (162 mg/week) [9], confirmed the promising results shown in a GCA open-label study in which TCZ was given intravenously at a dose of 8 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks [10]. Additional open-label studies have demonstrated the efficacy of TCZ in severe ocular complications, such as uveitis associated with Behçet’s disease and JIA refractory to conventional and biological immunosuppressive drugs, including anti-TNF agents [11,12]. Although the main monogenic autoinflammatory diseases are mostly caused by an uncontrolled increase of IL-1, TCZ has shown efficacy in several cases refractory to colchicine, anti-IL-1, and anti-TNF agents [13].

More familiar to rheumatologists and internists is the use of TCZ in adult-onset Still’s disease (AOSD), particularly in patients who are refractory to conventional therapies and present a predominant polyarticular pattern of the disease [14–16]. AOSD is a rare multisystem inflammatory disease of unknown origin that is included within the clinical spectrum of autoinflammatory disorders [16,17]. It shares many clinical and laboratory features as well as gene profile activation with systemic onset JIA, for which the usefulness of biologic therapies is also similar [16].

Around 15–20% of patients with AOSD develop some life-threatening events, being the macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), a secondary form of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), the most feared complication leading to high mortality rate [16]. It may occur as the first manifestation or during the disease course, usually associated with infections, drugs, or disease relapses [16,18,19]. In AOSD and other autoimmune diseases, MAS is characterized by high non-remitting fever, central nervous system dysfunction, involvement of the heart (as myocarditis or pericarditis) and lung (as acute respiratory distress syndrome), pancytopenia, coagulopathy, abnormally increased triglycerides, or hyperferritinemia (generally >5,000 mg/L) [16,19,20]. TCZ onset after adequate nonselective immunosuppressive therapy, such as pulses of methylprednisolone or a prednisone-based combination of immunosuppressants, can be an effective treatment for AOSD-associated MAS [18].

3. The role of tocilizumab and other anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive agents in COVID-19

Patients with COVID-19 present with features mimicking autoimmune diseases, such as fever, arthralgia, acute interstitial pneumonia, myocarditis, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and biological inflammatory changes derived from a cytokine storm, similar to HLH or MAS associated with autoimmune or inflammatory conditions [1,2,16,21,22].

COVID-19 patients may suffer severe complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome and death, which is finally provoked by an increased alveolar exudate and damage secondary to an abnormal local immune-inflammatory response. Based on the experience with TCZ in CAR-T cell-associated CRS and autoimmune diseases-related MAS [6,16,18–20], and the presence of a cytokine storm syndrome potentially causing fatal lung tissue damage, also responding to TCZ in patients with severe COVID-19 [1,2], TCZ and other anti-IL-6 agents (such as siltuximab and sarilumab) are being investigated in ongoing COVID-19 clinical trials in different countries.

With regard to anti-IL-1 therapy, anakinra has also shown benefit in patients with autoimmune diseases-associated MAS, both subcutaneously [18,19] and intravenously [16]. In severe COVID-19, some cases have similarly responded to the sole administration of anakinra at high doses by intravenous infusion (at 10 mg/kg/day during a mean of 9 days) [21] or by the subcutaneous route (at 100 mg/6 hours during 14 days) [22]. In addition, different clinical trials with intravenous anakinra are ongoing at this moment. In the same sense, several clinical trials using colchicine (as an inhibitor of inflammatory cell migration, also with anti-IL-1 properties) for treating COVID-19 patients are also being tested.

The role of conventional immunosuppressive agents in treating or preventing severe forms of COVID-19 is being analyzed. It is noticeable that patients with conditions characterized by drug-induced immunosuppression, such as those with autoimmune diseases or transplant recipients, were considered a priori to be at a higher risk for developing severe forms of COVID-19. However, some authors have postulated that low doses of tacrolimus in kidney transplant patients may attenuate the hyperinflammatory reaction leading to severe COVID-19 [23]. In a similar way, baseline immunosuppression with cytotoxic drugs (e.g. methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, etc.) or biologic agents (anti-IL-6, anti-IL-1, anti-TNF, JAK inhibitors, or B-cell depleting agents), or even previous immunomodulatory treatment (e.g. hydroxychloroquine or colchicine), might play a protective role in the development of the exaggerated immune-mediated inflammatory response associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases.

As in some preliminary reports [1,2], the real-word experience in COVID-19 patients with TCZ, mostly given in an early inflammatory phase, has shown a rapid resolution of fever and improvement of respiratory function and chest imaging changes, as well as the progressive reduction of inflammatory parameters such as CRP and ferritin. Our own experience also supports these observations with the use of this biologic agent in severe COVID-19 patients.

4. Our expert opinion in recognizing and treating COVID-19

From its occurrence in China first and Italy afterward, until the experience of having to deal with urgent solutions in our own country, we have learned how to recognize the different phases (or ‘faces’) of COVID-19, and also how to manage them. After the initial viral phase (‘face 1’) with variable symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic forms to overt clinical situations with fever, coughing, ageusia, anosmia, and upper respiratory airway involvement, some patients develop an immunologic and hyperinflammatory phase (‘face 2’), which is manifested with biological changes of a cytokine storm (macrophage activation-like) syndrome, usually accompanied by a quick respiratory deterioration due to a bilateral pneumonitis. A hypercoagulative status (‘face 3’) may be present in critically ill patients during the inflammatory phase, and mild to life-threatening thrombotic complications are quite frequent. Inflammatory pneumonitis and lung fibrotic changes (‘face 4’) have been also described in patients who have suffered from an acute and uncontrolled lung involvement. Finally (by now), dermatologic (mainly with pseudo-chilblain and vesicular lesions) and coronary inflammatory changes, probably related to immune-mediated vasculitic-like lesions, may be developed by young patients in a delayed phase (‘face 5’).

Although the exact role of an effective antiviral therapy and the best moment for its administration have to be determined yet, most of the clinical studies in real life have identified that a delay in applying the correct anti-inflammatory treatment may influence negatively in the outcome of COVID-19 patients. However, these hypotheses have also to be unveiled in the near future after knowing the results of different clinical trials. In the meantime and with the only aim of saving lives, many (urgent) clinical guidelines and standardized working protocols for managing admitted patients with COVID-19 have been similarly used with a real low level of evidence during the outbreak.

While the first-line therapy in all patients with COVID-19 has been based in hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine, azithromycin, and lopinavir/ritonavir combinations, without showing clear benefit in most clinical studies [24–26], and while remdesivir is still pending to be validated as a clear option [27], in patients with a moderate to severe disease (defined by the presence of hypoxemia due to a bilateral pneumonia, usually associated to increased inflammatory markers, especially CRP and ferritin), the prompt use of glucocorticoids at high doses and/or intravenous TCZ (ideally at 8 mg/kg) has become the treatment of choice in real life. In this regard, the first retrospective and observational studies using glucocorticoids [28] and tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 have shown promising results [1,2].

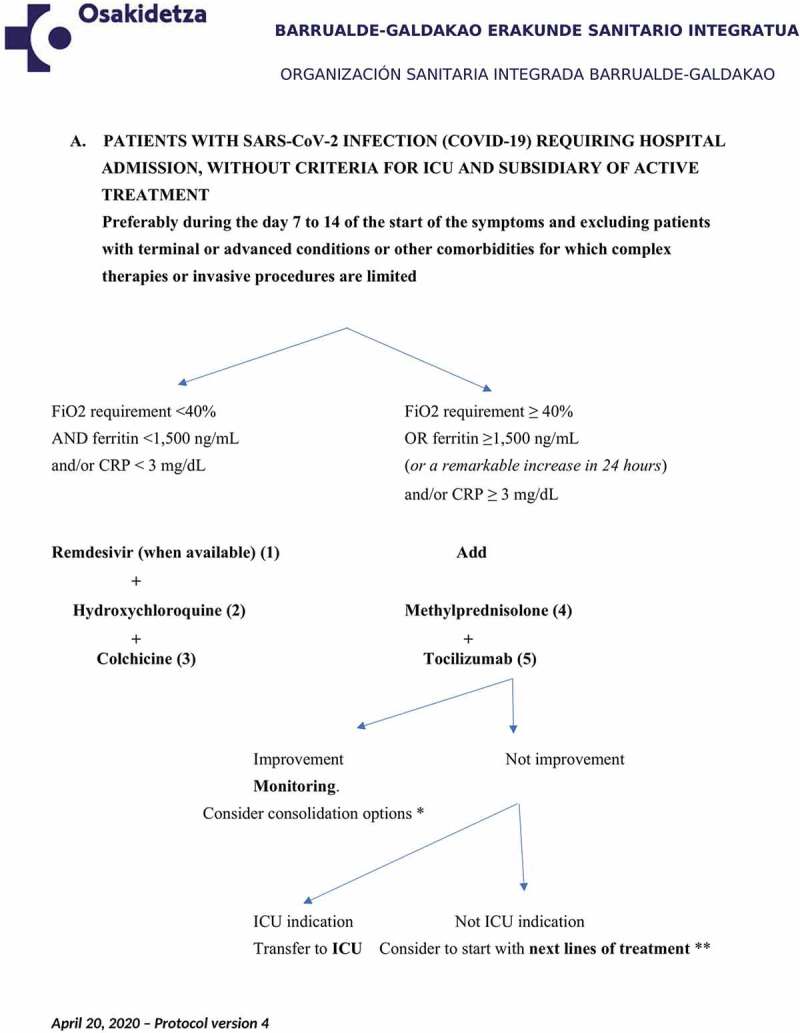

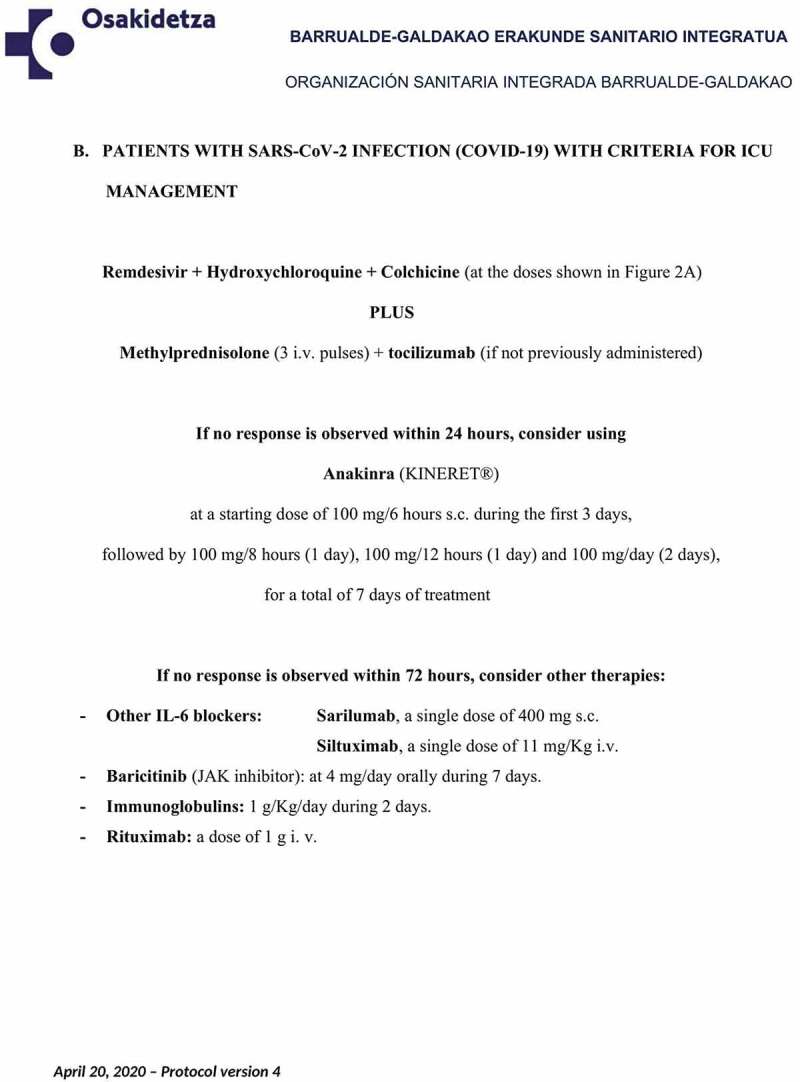

Herein, we intend to show the collaborative and multidisciplinary protocol for managing COVID-19 at Hospital Galdakao (Bizkaia, Spain), elaborated with the participation of all the authors (Figures 2A and 2B). The protocol was adjusted several times during the entire outbreak period, and the last version at this time (20 April 2020) has been included. For mild COVID-19 cases, a combination of hydroxychloroquine and colchicine (with remdesivir, if available) was used. For moderate to severe cases, depending on the respiratory severity (FiO2 requirement ≥40%) and levels of ferritin (≥1,500 ng/mL) and/or CRP (≥3 mg/dL), the prompt administration (during the first 7 to 14 days of the beginning of the symptoms) of intravenous methylprednisolone (250 mg/day during 3 days) and a single infusion of TCZ (600 mg in patients ≥75 Kg, limited by the Spanish Ministry of Health) was given with the intention of avoiding patient transfer to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or, if ICU was required, these drugs were still administered to avoid invasive ventilation. In non-responsive cases, anakinra was subcutaneously administered at doses of 100 mg/6 hours for 3 days, followed by daily reductions of 100 mg until maintain 100 mg/day during a total of 7 days. In our hands, this scheme of management yielded good results in hospital wards and also in ICU (data not published, still under analysis).

Figure 2A.

Treatment protocol for COVID-19 – Part I.

(1) Remdesivir (from Gilead Sciences): loading dose of 200 mg i. v. on day 1, then 100 mg i.v. for the following 9 days. Only antiviral likely active, trials currently ongoing.(2) Hydroxychloroquine (DOLQUINE®): 200 mg per tablet; 2 tablets (400 mg)/12 hours the first 24 hours, and subsequently, 1 tablet (200 mg)/12 hours; duration of treatment 7–14 days.(3) Colchicine (COLCHICINA SEID®): 0.5 mg per tablet; 1 tablet (0.5 mg)/12 h for 3 days, followed by 0.5 mg/day during a total of 7 days.(4) Methylprednisolone (URBASON®): 250 mg i.v./day x 3 days.(5) Tocilizumab (RoACTEMRA®): if possible, an i.v. dose of 8 mg/Kg. However, due to a shortage of stock, a dose per patient was authorized, of 600 mg (if weight ≥75 Kg) or 400 mg (if weight <75 Kg).* Additional dose of tocilizumab if available or a similar anti-IL6 agent (e.g. sarilumab, siltuximab) or anakinra (according to doses in Part II – Figure 2B).** Specified in the following section (ICU)

Figure 2B.

Treatment protocol for COVID-19 – Part II.Adapted with permission from the updated protocol proposed on 20 April 2020, by Dr. Mayo at Hospital Galdakao, Bizkaia, Spain (anticoagulation recommendations not included).

In conclusion, while conventional biologic markers (ferritin, CRP, etc.) or cytokine measurements (circulating levels of IL-6, IL-1 receptor-antagonist, among others) have to be determined as prognostic factors for COVID-19 in still required rigorous studies, and while the results of still pending clinical trials will shed the ultimate light on the accurate management of COVID-19, at this moment, we strongly support a proactive and early management with the administration of glucocorticoids and anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-1 agents in critically ill patients, or in those with a rapidly progressive disease in the context of a hyperinflammatory state. By doing so, the progression to the different phases and faces of COVID-19 will be probably minimized or avoided. Indeed, to achieve these goals faster and better, we believe we have worked together, in multidisciplinary teams, from the beginning.

Funding Statement

This paper is not funded.

Declaration of interest

MA Gonzalez-Gay has received grants/research supports from Abbvie, MSD, Jansen and Roche, and had consultation fees/participation in company sponsored speaker´s bureau from Abbvie, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Lilly, MSD and Novartis. S Castañeda has received grants/research supports from MSD and Pfizer, consultation fees/participation in company sponsored speaker´s bureau from Amgen, MSD, Lilly, Sobi and Pfizer. J Hernández-Rodríguez has participated in Sobi, Novartis and Roche sponsored educational activities and has received consultation fees from Sobi. J Cifrián participated in Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD and Roche sponsored educational activities. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. The remaining authors have nothing to declare.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Xu X, Han M, Li T, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020. April 29:202005615. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Outstanding report of an initial Chinese series of 20 patients with severe COVID-19 treated with tocilizumab with satisfactory results.

- 2.Toniati P, Piva S, Cattalini M, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe COVID-19 pneumonia with hyperinflammatory syndrome and acute respiratory failure: A single center study of 100 patients in Brescia, Italy. Autoimmun Rev. 2020. May 3:102568. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A study-series of 100 consecutive patients with confirmed severe COVID-19 requiring ventilatory support who were treated with intravenous tocilizumab, obtaining rapid, sustained, and significant clinical improvement.

- 3.Srirangan S, Choy EH.. The role of interleukin 6 in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2010;2:247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Excellent review on the role of IL-6 in the mechanisms associated with inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. It describes in an elegant way the inflammatory pathways activated by IL-6.

- 4.Sebba A. Tocilizumab: the first interleukin-6-receptor inhibitor. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • In this report the author provided useful information on the pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, clinical efficacy, safety, and role of tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis

- 5.Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Review on the role of IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling in the tumor microenvironment and the status of preclinical and clinical investigations of agents targeting this pathway. The authors also discussed the potential of combining IL-6/JAK/STAT3 inhibitors with therapeutic agents directed against immune-checkpoint inhibitor.

- 6.Le RQ, Li L, Yuan W, et al. FDA Approval Summary: tocilizumab for Treatment of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell-Induced Severe or Life-Threatening Cytokine Release Syndrome. Oncologist. 2018;23:943–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Tocilizumab proved to be useful for the treatment of severe or life‐threatening chimeric antigen receptor T cell‐induced cytokine release syndrome.

- 7.Biggioggero M, Crotti C, Becciolini A, et al. Tocilizumab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: an evidence-based review and patient selection. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;13:57–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Outstanding review article on tocilizumab and its efficacy in the management of rheumatoid arthritis.

- 8.Yokota S, Itoh Y, Morio T, et al. Tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a real-world clinical setting: results from 1 year of postmarketing surveillance follow-up of 417 patients in Japan. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1654–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Study showing the efficacy of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, a chronic inflammatory disease that in some cases may be associated with the development of a macrophage activation syndrome.

- 9.Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of Tocilizumab in Giant-Cell Arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A randomized controlled trial confirming the efficacy of tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis, the most common vasculitis in people 50 years and older from Western countries.

- 10.Loricera J, Blanco R, Hernández JL, et al. Tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis: multicenter open-label study of 22 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44:717–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Data supporting the efficacy of tocilizumab in real-world giant cell arteritis patients. In this open-label study tocilizumab led to clinical improvement in most cases. Significant reduction of acute phase proteins and prednisone dose was also achieved.

- 11.Atienza-Mateo B, Calvo-Río V, Beltrán E, et al. Anti-interleukin 6 receptor tocilizumab in refractory uveitis associated with Behçet’s disease: multicentre retrospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57:856–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Study showing the efficacy of tocilizumab in a large series of patients with uveitis due to Behçet’s disease refractory to conventional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs and anti-TNF agents.

- 12.Calvo-Río V, Santos-Gómez M, Calvo I, et al. Anti-Interleukin-6 Receptor Tocilizumab for Severe Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis Refractory to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy: A Multicenter Study of Twenty-Five Patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:668–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Tocilizumab yielded beneficial effects in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated uveitis refractory to TNF inhibitors.

- 13.Soriano A, Soriano M, Espinosa G, et al. Current therapeutic options for the main monogenic autoinflammatory diseases and PFAPA syndrome: evidence-based approach and proposal of a practical guide. Front Immunol. 2020;11:865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Exhaustive review focused on conventional and biologic therapies available (including colchicine, anakinra and tocilizumab) for the main monogenic autoinflammatory diseases and PFAPA syndrome.

- 14.Castañeda S, Martínez-Quintanilla D, Martín-Varillas JL, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of adult-onset Still’s disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Review article that discussed in depth the use of tocilizumab in adult-onset Still’s disease.

- 15.Ortiz-Sanjuán F, Blanco R, Calvo-Rio V, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in conventional treatment-refractory adult-onset Still’s disease: multicenter retrospective open-label study of thirty-four patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1659–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Real-world study confirming the efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with adult-onset Still’s disease who were refractory to other therapies.

- 16.Mehta P, Cron RQ, Hartwell J, et al. Silencing the cytokine storm: the use of intravenous anakinra in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis or macrophage activation syndrome. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020. May 4. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An interesting case-series of patients with secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis or macrophage activation syndrome associated to autoimmune diseases, in whom intravenous anakinra administration at high doses led to a clinical and biological resolution.

- 17.Hernández-Rodríguez J, Ruiz-Ortiz E, Yagüe J. Monogenic autoinflammatory diseases: general concepts and presentation in adult patients. Med Clin (Barc). 2018;150:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Interesting review about clinical presentation of autoinflammatory diseases in adult patients.

- 18.Watanabe E, Sugawara H, Yamashita T, et al. Successful Tocilizumab Therapy for Macrophage Activation Syndrome Associated with Adult-Onset Still’s Disease: A Case-Based Review. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:5656320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Study supporting the efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with macrophage activation syndrome associated with adult-onset Still’s disease.

- 19.Lenert A, Oh G, Ombrello MJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and comorbidities in adult-onset Still’s disease using a large US administrative claims database. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020. January 21:pii: kez622. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Large series of patients with adult-onset Still’s disease showing macrophage activation syndrome manifestations, which included the inflammatory involvement of the lungs as acute respiratory distress syndrome.

- 20.Gavand PE, Serio I, Arnaud L, et al. Clinical spectrum and therapeutic management of systemic lupus erythematosus-associated macrophage activation syndrome: A study of 103 episodes in 89 adult patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A large series of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus developing a macrophage activation syndrome with pulmonary inflammatory changes.

- 21.Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, et al. Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020. May 7. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Interesting series of 29 patients with severe COVID-19 in whom anakinra at high doses (10 mg/kg/day intravenously) showed better results than lower doses (100 mg twice a day subcutaneously) in terms of mechanical ventilation-free survival and mortality.

- 22.González-García A, García-Sánchez I, Lopes V, et al. Successful treatment of severe COVID-19 with anakinra as a sole treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020. [in press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This is the first case reported of a patient with severe COVID-19 treated with anakinra alone during 14 days with good response.

- 23.Ahmadpoor P, Rostaing L. Why the immune system fails to mount an adaptive immune response to a COVID-19 infection. Transpl Int. 2020. April 1. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Editorial that nicely reviews different potential etiopathogenic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the associated immune-mediated inflammatory response. The authors also provides with the idea of the potential protective role of low doses of immunosuppressive agents in immunocompromised patients, such as kidney transplant recipients.

- 24.Geleris J, Sun Y, Platt J, et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020. May 7. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • An observational study of 1,446 consecutive patients of COVID-19 hospitalized, in whom hydroxychloroquine did not provide any benefit to avoid intubation or death.

- 25.Cheng CY, Lee YL, Chen CP, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir did not shorten the duration of SARS CoV-2 shedding in patients with mild pneumonia in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;S1684–1182(20)30092–X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Lopinavir/ritonavir was not associated with a shorter duration of viral shedding during the first ten days of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to patients not receiving the combination.

- 26.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A randomized, controlled, open-label trial of 199 hospitalized adult patients with severe COVID-19, for whom lopinavir-ritonavir treatment was not associated with any improvement compared with the standard care.

- 27.Mahase E. Covid-19: remdesivir is helpful but not a wonder drug, say researchers. BMJ. 2020. May;1(369):m1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • In this opinion article, the author explains that the current evidence to support remdesivir in COVID-19 patients is still poor.

- 28.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;e200994. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This retrospective Chinese series of 201 patients with COVID-19 showed that in patients developing acute respiratory distress syndrome, treatment with high doses of glucocorticoids is associated with a reduced mortality, compared with patients not receiving them.