Highlights

-

•

We estimated CO2 emission reductions in different sectors in China due to COVID-19.

-

•

Industry sector contribute the most significant absolute CO2 emission decrease.

-

•

Energy-related CO2 emissions decreased by 18.7% (182 MtCO2) in first quarter of 2020.

-

•

Economic stimulus packages may increase CO2 emission growth rate in coming years.

Keywords: China, CO2 emissions, COVID-19, Energy consumption

Abstract

Coronavirus has confined human activities, which caused significant reductions in coal, oil, and natural gas consumptions in China since January of 2020. We compile industrial, transport, and construction data to estimate the reductions in energy-related CO2 emissions during the first quarter of 2020 in China. Our results show that the fossil fuel related CO2 emissions decreased by 18.7% (182 MtCO2) in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period last year, including reductions of 12.2% (92 MtCO2) in industry sectors, 61.9% (62 MtCO2) in transport, and 23.9% (28 MtCO2) in construction. The figure in annual CO2 emission reductions is expected to limit with an estimate of 1.6%. However, to achieve the economic target for the 13th Five-Year-Plan, stimulus packages including investments in “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects issued by China’s central and local governments to response the COVID-19 may increase CO2 emissions with a higher speed in the coming years. Thus, sustainable stimulus packages are needed for accelerating China’s climate goals.

1. Introduction

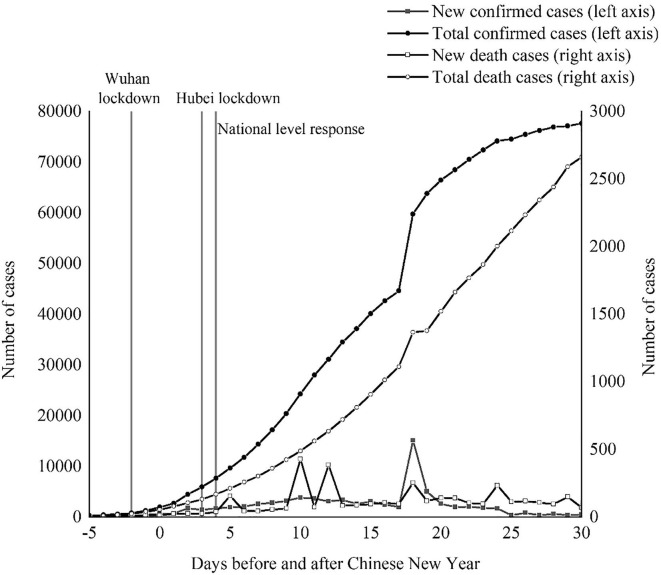

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease that has been creating panic over the last few months and had led to about 193,000 deaths and more than 2,800,000 confirmed diagnosis worldwide by the end of April 2020 [1]. Chinese government has adopted prompt and effective confined measures to limit the spread of the virus (Fig. 1 ). Although the effect of enforcing these aggressive measures to control the transmission in China and the world is undoubtedly enormous, the economic impacts of this disease outbreak were significant too. Every sector of the economy – from industry, transport, and construction, to catering services – has been feeling the effects. The epidemic has shut factories, disrupted travels, closed construction sites, cut off communities, and shook up economic markets. As a result, the preliminary accounting of China's GDP decreased by 6.8% in the first quarter of 2020 year-on-year, in which the growth rates of primary, secondary, and tertiary industries were −3.2%, −9.6% and −5.2%, respectively [2]. Besides, the economic activities were nearly at a standstill in China, which reduced energy consumptions and related CO2 emissions as well. In this study, we estimated how much the CO2 emissions decreased in the first quarter compared with the same period of last year due to the COVID-19 and then analysis the possible effect on CO2 emissions in medium- and long-term in China.

Fig. 1.

Confirmed and death cases in China. X-axis shows days before and after Chinese New Year in 2020. The three vertical grey reference lines refer to Wuhan lockdown in January 23, Hubei lockdown in January 28, and National level response launched in January 29, respectively. Data Source: National Health Commission.

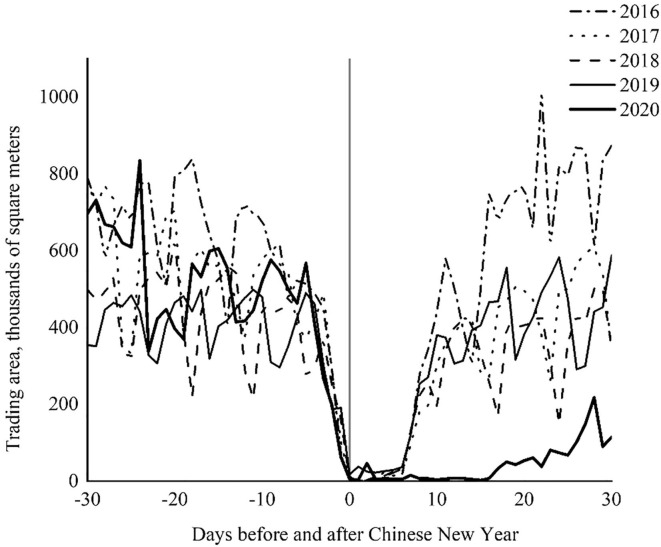

Accommodation and restaurant suffered the most as their output dropped by 35.5% in the first quarter of this year. Fear of the epidemic kept people at home and tourists away. Moreover, local governments have taken different degrees of traffic control measures to reduce the flow of people, and most people in China were restricted on movement and enforced home quarantine for two weeks or longer. Output in wholesale and retail trades were secondly most affected, which reduced by 17.8% in the first quarter. Real estate has been hit hard with a −6.1% growth rate in the first quarter compared with the same period last year [2]. In addition, the daily trading area of commercial housing in China’s 30 large- and medium-sized cities fell by 34% on the first quarter year-on-year (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Trading area of commercial housing in 30 large- and medium-sized cities. Daily trading area of commercial housing in 30 large- and medium-sized cities around the Chinese New Year period, in 1000 square meters per day. X-axis shows days before and after Chinese New Year, which located in different dates in different years. Data Source: WIND Information.

Meanwhile, import and export have also been significantly impacted by the epidemic. According to the General Administration of Customs of China, in the first quarter of this year, China’s foreign trade volume in goods was RMB 6.57 trillion, dropped by 6.4% year-on-year (similarly hereinafter). Among them, exports were RMB 3.33 trillion, decreased by 11.4%; imports were RMB 3.24 trillion, reduced by 0.7%. The trade deficit was RMB 98.33 billion, dropped by 80.6% [3].

History indicates that economic downturns tend to lead to a temporary decline in CO2 emissions, and then, there will be a rapid growth in CO2 emissions after the downturns with the economic recover [4]. The global financial crisis of 2008–2009, for example, was accompanied by a temporary decrease (−1.4%) in global CO2 emissions, and the emissions from fossil-fuel combustion and cement production grew by 5.9% in 2010, which was the highest total annual growth recorded since 2003 [5]. As for this crisis, the epidemic has led to reductions in energy consumptions and industry outputs, which indicates a reduction in CO2 emissions in short-term, while the medium- and long-term emissions will depend on the government’s actions and stimulus packages after the pandemic. The International Monetary Fund and Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecasted that the global CO2 emissions would increase by 5.8% in 2021.

Many researchers have studied the changes in energy demand and related CO2 emissions due to the COVID-19 both at the global and national levels. From a global perspective, Le Quéré et al. used government policies and activity data to estimate the decrease in CO2 emissions during forced confinements and reported that the CO2 emissions would decrease by 4% if pre-pandemic conditions return by mid-June, and decrease by 7% if some restrictions remain worldwide until the end of 2020 [6]. International Energy Agency showed that the global energy demand decreased by 3.8% during the first quarter of 2020 compared the same period of 2019 and the annual energy demand would decline by 4–6% in 2020 [7]. Liu et al. also provided a prediction on the COVID-related reductions in global CO2 emissions in road transportation (340.4 MtCO2, −15.5% compared to 2019), power (292.5 MtCO2, −6.4%), industry (136.2 MtCO2, −4.4%), aviation (92.8 MtCO2, −28.9%), residential (43.4 MtCO2, 2.7%), and international shipping (35.9 MtCO2, −15%) [8].

China is currently the largest energy consumer and CO2 emitter in the world, accounting for approximately 30% of global emissions [9], therefore any significant changes happened in China will have a direct and significant influence worldwide. There has been some estimation on changes in China's energy consumption and CO2 emissions due to the COVID-19. For instance, Han et al. used gross domestic product (GDP) and an inventory (China Emission Accounts and Datasets, CEADs) to estimate the decrease in CO2 emissions in the first quarter of 2020 at national and regional levels, and implied that the lower coal consumption and cement output contribute largely to total CO2 emission reductions [10]. Myllyvirta shows that China’s carbon emissions fell by around 18% over a seven-week period compared with the same period last year [11].

These studies provide pioneering assessments of the extent of COVID-19 impacts on CO2 emissions in 2020 and reached profound impacts on public and academia. However, few studies have provided a comprehensive and quantitative assessment to distinguish the decrease of energy-related CO2 emissions due to COVID-19 from different sectors of China. Furthermore, estimation regarding the medium- and long-term impacts on CO2 emissions derived from the stimulus policies issued by Chinese government to response this crisis is still lacking. In this study, we first estimate the CO2 emission changes from electric power generation, coking, steel, methanol, transport, and construction specifically, and then use these results to estimate the decline of CO2 emissions in the whole country. Furthermore, we analyze the medium- and long-term effects on CO2 emissions of the stimulus packages in China.

China’s energy use is mainly dominated by six energy-intensive industrial sectors and transport sector, whose CO2 emissions accounted for 83.9% of China’s total CO2 emissions in 2017. Considering the availability of data, the degree of impact, and the proportion of CO2 emissions for each sector, changes in energy-related CO2 emissions were estimated for these sectors and construction activity as well. According to the Statistical Report of National Economic and Social Development, the six energy-intensive industries are production and supply of electric power, petroleum processing and coking, raw chemical materials and chemical products, nonmetal mineral products, smelting and pressing of ferrous metals, and smelting and pressing of nonferrous metals, in which 62.5% of total CO2 emissions came from the electricity and heat production, while the other five sectors covered 14.3%, and the transport contributed 7.1% of total CO2 emissions. We collected time-series data representing changes in activity, such as coal demands in electric sector or operating rate of production, to estimate the percentage changes in CO2 emissions instead of the absolute volume changes in CO2 emissions in corresponding sectors.

The remaining paper is organized as follows. Sector 2 introduces the method and data for estimating CO2 emission changes. Sector 3 reports the estimation results for six sectors and the whole country. The discussions regarding the medium- and long-term impacts and the policy implications are provided in Sector 4.

2. Method and data for estimating CO2 emission changes

2.1. CO2 emissions in 2019

The CO2 emissions and sectoral structure data in 2017 are from CEADs. We assume that change rate of CO2 emissions is equal to the annual growth rate in total energy consumptions (billion tons of standard coal equivalent) reported on the Statistical Communique [12], [13]. Then the CO2 emissions in 2019 for China can be estimated as follows:

| CO2 emissions2019 = CO2 emissions2017 × AGR2018 × AGR2019 | (1) |

where CO2 emissions2019 and CO2 emissions2017 indicate the total fossil fuel related CO2 emissions of China in 2017 and 2019 respectively. AGR 2018 and AGR 2019 denote the annual growth rates in total energy consumptions of 2018 and 2019, respectively.

2.2. Change rate of CO2 emission in industry sector

According to the proportion of CO2 emissions in 2017, our estimations of change rate of CO2 emissions in industrial sectors include electric power generation, coking, steel, and chemical. Following the method of Myllyvirta [11], we estimate the year-on-year change rates of CO2 emissions in industry sectors using sector activity indicators: daily coal consumptions at power generation groups, operating rates in coking plant, blast furnace and steel plant, and oil refinery plant. The coal consumption and operating rate data were collected from WIND Information.

We use total coal consumptions at six major power generation groups to calculate the change rate of CO2 emissions in electric power generation. Specifically, we assume the CO2 emissions in electric power generation have a positive linear relationship with the total coal consumptions, thus the emission change rate in electric power generation is estimated as follows:

| (2) |

where CRE refers to the change rate of CO2 emissions in electric power generation, i indicates months - January, February and March - in the first quarter of 2020, TCCi denotes the total coal consumptions at six major power generation in month i, CRTCCi reflects the change rate of total coal consumptions in month i compared with the same period of last year.

We assume that the emission factors and the energy structure remain unchanged for each sector in 2020 compared with 2019. Hence, the change rate of the CO2 emissions in coking, steel, and chemical can be estimated according to the change rate of operating rate in 2020 compared with the same period of 2019, as follows:

| (3) |

in which CRI refers to the change rate of CO2 emission in each sector of coking, steel, and chemical in the first quarter of 2020, ORi represents the operating rate of corresponding sector in month i, CRORi refers to the change rate of operating rate of corresponding sector in month i. In addition, we adopt their CO2 emission proportions in 2017 as the weights to aggregate these change rates of CO2 emissions into a single indicator of CO2 emission change rate in industrial sector.

2.3. Change rate of CO2 emissions in transport

For transport sector, in the absence of energy consumption related information, we assume the decrease of number of passengers sent by railway and civil aviation in the first quarter of 2020 year-on-year to be the decrease in CO2 emissions of transport. The data were obtained from the Ministry of Transport of China. Thus, the change rates of CO2 emissions in transport is calculated as follows:

| (4) |

in which CRT represents the change rates of CO2 emissions in each sector of railway and civil aviation in the first quarter of 2020, NPi indicates the number of passengers sent by corresponding sector in month i, CRNPi denotes the change rates of corresponding number of passengers sent by railway or civil aviation in month i compared with the same period last year. The emission change rates of railway and civil aviation are aggregated into a single measure of change rate of CO2 emissions in transport with the total energy consumptions of railway and civil aviation in 2018 as weights.

2.4. Change rate of CO2 emissions in construction

The calculation of emission change rate for the construction is relatively straightforward. We assume that the change rate of CO2 emissions in construction is equal to the change rate in cement output. We collected the monthly cement output data from National Bureau of Statistics [14] and estimate the year-on-year change rate of CO2 emissions in construction as follows:

| (5) |

in which CRC is the change rate of CO2 emissions in the first quarter of 2020 in construction, is the cement output in month i in 2020. CRCOi is the change rate of cement output in month i of 2020 compared with the same period in 2019.

3. Results

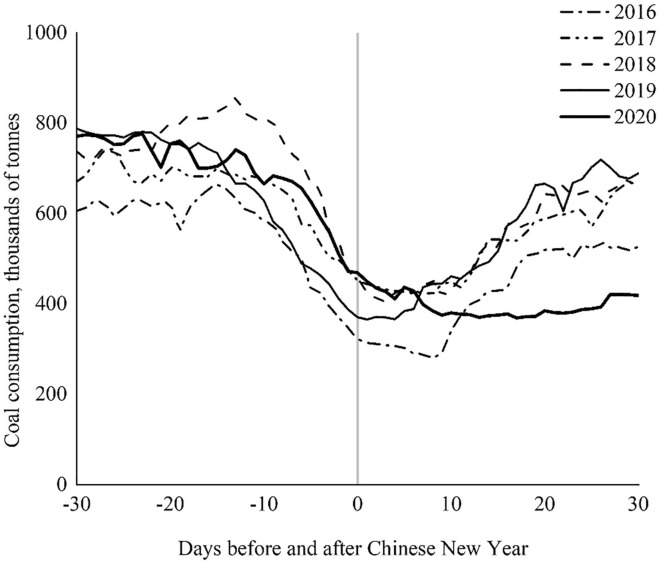

3.1. CO2 emissions from electric power generation would drop by 16%

As shown in Fig. 3 below, the daily total coal consumptions at six major power generation groups usually drop by an average of 50% in the 10 days commencing the Chinese New Year, and then rebound. However, in this year, in order to get the epidemic under control, the Chinese New Year holiday had been extended for 10 days (and even longer in some provinces) and many factories prolonged shutdown. In the 30 days period following the Chinese New Year, average daily coal consumption at power plants was still 30% lower than the same period of last year. According to the daily coal use data in the first quarter of this year, the CO2 emissions from the electric power generation would drop by 16% over the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period of last year.

Fig. 3.

Daily coal consumption at six major power generation groups. Daily total coal consumption around the Chinese New Year at six major power generation groups, in 1000 tonnes per day. Data Source: WIND Information.

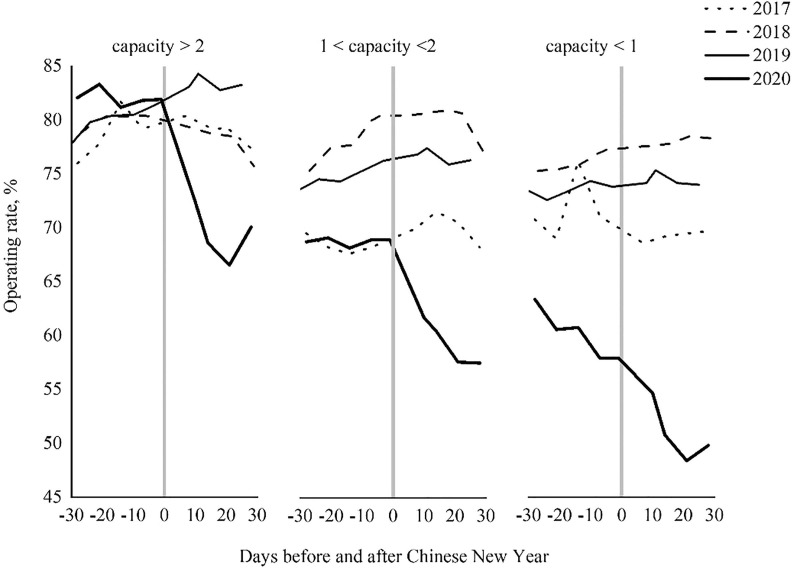

3.2. CO2 emissions from coking would reduce by 8%

As Fig. 4 shows, the operating rate of coking industry has decreased sharply after the Chinese New Year. Compared with the same period in 2019, at the end of this February, the operating rates of coking industries decreased by 30%, 21%, and 6% in the factories with production capacities less than 1 million tonnes, between 1 and 2 million tonnes, and greater than 2 million tonnes, respectively. This indicates that the CO2 emissions of the coking industry in the first quarter would drop by approximately 8%.

Fig. 4.

Operating rate of coking industry. Operating rate of coking industry (%) around Chinese New Year. The units of capacity are 1,000,000 tonnes. Data resource: WIND Information.

3.3. CO2 emissions from steel industry would reduce by 9.8%

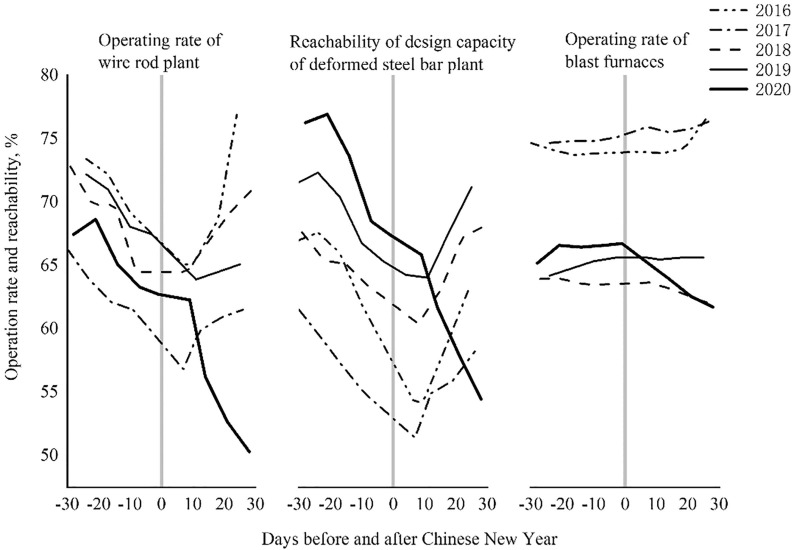

Similarly, the indicators for steel industry capacity utilization deteriorated further in 30 days after Chinese New Year (Fig. 5 ). In the first quarter of this year, compared with the same period in 2019, the operating rate for wire rod plant dropped by 10.6%; the reachability of design capacity for deformed steel bar plant dropped by 8.5%; and the operating rate for blast furnaces in February 2020 decreased by 4.3% compared with the same period in 2019. Therefore, the CO2 emissions from steel industry would reduce by 9.8% in the first quarter of this year compared with the same period of last year.

Fig. 5.

Operation rate and reachability in steel industry. Operating rate for wire rod plant (%), reachability of design capacity for deformed steel bar plant (%), and operating rate for blast furnaces (%) around Chinese New Year. Data resource: WIND Information.

3.4. CO2 emissions from methanol would decrease by 1.6%

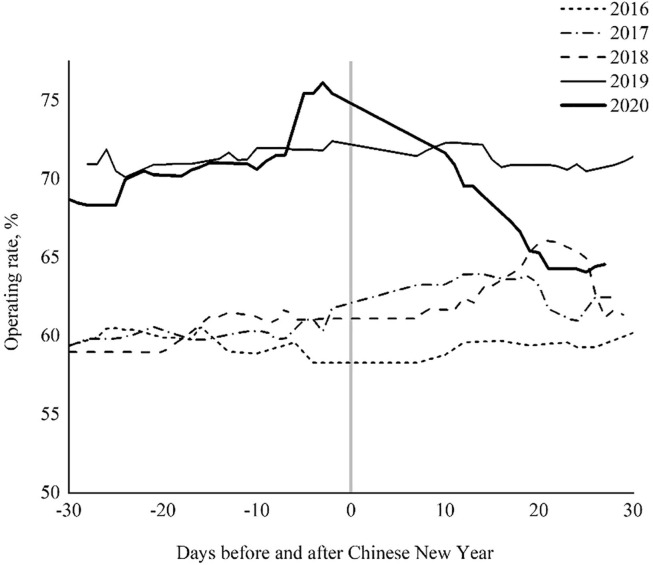

The operating rate for methanol production (Fig. 6 ), one of the representative operating rates for raw chemical materials and chemical products industry, dropped dramatically commencing the Chinese New Year. It typically kept stable or slightly increased during the holiday in the last few years. However, at the end of this February, the methanol’s operating rate decreased by 7% compared with the same period in 2019. In the first quarter of 2020, the CO2 emissions from raw chemical materials and chemical products industry would decrease by 1.6%.

Fig. 6.

Operating rate of methanol production. Operating rate of methanol production (%) around Chinese New Year. Data resource: WIND Information.

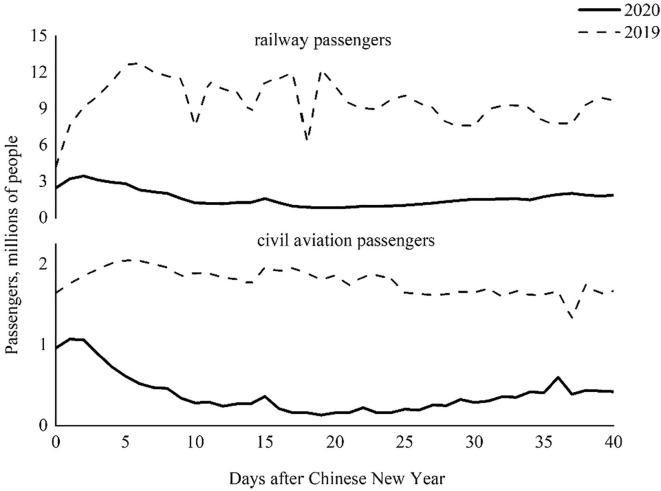

3.5. CO2 emissions from transport would decrease by 62%

By the end of this February, the number of passengers sent by railway and civil aviation within China decreased by 77.7% and 74.9%, respectively, compared with the same period in 2019, and remained at low levels commencing the Chinese New Year (Fig. 7 ). The suspensions and cancellations in trains, high-speed rails, and flights would lead to a reduction of 62% in CO2 emissions in transportation in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period of 2019.

Fig. 7.

Passengers sent by railway and civil aviation. Daily passengers sent by railway and civil aviation after the Chinese New Year, in 1,000,000 people per day. Data Source: WIND Information.

3.6. CO2 emissions from construction would drop by 23.9%

The construction activity was affected as migrant workers who were not allowed to move or flow for weeks and couldn’t return to cities after the Chinese New Year. In addition, insufficient supply of raw materials for the construction and stagnated investment in infrastructure has also caused some impacts in the short-term. The output in construction decreased by 17.5% in the first quarter [2], and, in consequence, the CO2 emissions from the construction would drop by 23.9% in the first quarter year-on-year.

3.7. China’s total CO2 emissions would reduce by 18.7% in the first quarter

To sum up, according to the estimations of the above-mentioned sectors, China’s total CO2 emissions would reduce by 18.7% (182.47 MtCO2) in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period of 2019 due to the coronavirus pandemic. This is in line with the estimations of Le Quéré et al. [6] and Han et al. [10] The former took into account temporary reductions in daily global CO2 emissions and reported that from the beginning of confinement to the end of April, the changes in CO2 emissions were large with a decrease of 242 MtCO2 in China. The latter used domestic economic data to assess the recent impact which shows that China’s CO2 emissions decreased by 257.7 MtCO2 in the first quarter of 2020.

Although the first quarter impact of the current epidemic is large, with respect to CO2 emissions, the annual figure would only reduce by around 1.6%. For comparison, Le Quéré et al. provided a projection of a reduction in emissions of 2.6% in 2020 in China with an assumption that the economic activities would recover to pre-crisis level in around mid-June [6], while the forecast of Myllyvirta showed a 1% reduction in CO2 emissions in 2020 [11]. Han et al. reported that the decreases were estimated at 3.9% to 7.4% depending on the duration of this crisis [10].

Before the outbreak of the COVID-19, several organizations and researchers had predicted that China’s energy consumptions and related CO2 emissions would keep increase during 2020. In the latest outlooks of China's energy for 2040, the main prediction scenario of EIA is that the average annual growth rate of China's primary energy demand would be 0.8%, while the forecasts of Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and British Petroleum were more optimistic which are around 1.1% and 1.2% [15], [16], [17]. China National Petroleum Corporation expected average annual primary energy demand to grow by 2.4% between 2015 and 2020 and the country’s CO2 emissions to peak (10 GtCO2) between 2025 and 2030 [18]. These forecasts, based on complex mathematical theories and a large amount of historical data, are considered with high reference value. They implied the energy consumptions and CO2 emissions in China should have increased without this crisis. In other words, the COVID-19 has temporarily reduced the energy consumptions and related CO2 emissions, but there is a great chance that the CO2 emissions would rebound after the pandemic if there is no significant change on energy consumption structural or substantial improvement on energy use efficiency.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Stimulus packages may increase CO2 with a higher speed in the coming years

We have seen reductions in CO2 emissions in the first quarter, particularly in industry and transport. However, this reduction tends to be temporary, because this is the result of reduced economic activities instead of new development policies issued by the governments, structural changes in the economic systems, or improvement in energy efficiency. As stimulus packages – such as a policy loosening for allowing new coal plant to be established in February [19] – make economic activities back up, the CO2 emissions would most likely increase with a higher speed in the coming years.

At the end of this March, China’s central government emphasized again to achieve the economic and social development targets for the 13th Five-Year-Plan, including the goal of doubling GDP by the end of 2020 compared with the 2010′s level. This goal would require an almost 6% GDP growth in 2020 [11]. Given the fact that China's preliminary accounting GDP dropped by 6.8% in the first quarter [2], stimulus packages for economic growth during the rest of the year would be most likely on the way.

There will be medium- and long-term consequences for energy consumptions and related CO2 emissions from how countries boost their economies with short-term stimulus measures [20], [21], [22]. During previous economic crises, China tend to adopt stimulus packages including investments in “shovel-ready” infrastructure projects – establishing coal-fired power plants, building roads, railways, and airports, or investing in energy-intensive industries such as cement and steel – which definitely means more fossil CO2 emissions. Back to the 2007–2010 period, for example, China’s CO2 emissions induced by capital formation grew rapidly as a result of stimulus spending that boosted fossil fuel use in the wake of the global financial crisis [23]. However, Chinese government tends to fall back on high-carbon projects to response this crisis. Lots of plans for building new coal-fired power plants in China, which have been put on ice in pursuit of renewable energy, could be revived rapidly if the focus is purely on economic growth [24]. Moreover, the investment scale of China's infrastructure is still a relatively large part of the country's overall investment. According to the disclosed specific investment plans of local governments in 2020, investment in infrastructure accounts for more than half of the total amount in some provinces.

Continuing the old way to respond to the COVID-19 disease may increase the CO2 emissions in medium- and long-term. Furthermore, it has two additional limitations. First, it may counter to the government’s goal about CO2 emissions, such as to reduce CO2 emissions per unit of industrial value added by 22% in 2020 compared with that in 2015. Second, it may miss the opportunity to develop low-carbon economy. A low-carbon economy is an economy based on low carbon power sources and needs to save energy and reduce greenhouse in order to keep sustainable economic and social development in the process of production and consumption [25]. In China, the cost of wind power is already lower than that of coal-fired power, and the cost of solar power is expected be lower than that of coal-fired power as well by the end of this year [19]. In addition, the return from investment in oil and gas is very close to that from solar and wind projects nowadays [26]. Hence, it’s a good opportunity to optimize the structure of energy systems (e.g. using clean energy to substitute for traditional fossil energy), which could both reduce the CO2 emissions to accelerate China’s climate goals and alleviate air pollution in China.

4.2. Sustainable stimulus packages will accelerate climate goals

The effects of coronavirus may be severe but likely to be temporary. However, the threat of climate change remains and will continue. The United Nations Environment Programme has pointed out that if we rely only on the current climate commitments of the Paris Agreement, global temperature is expected to rise by 3.2 °C at the end of this century. Collectively, we must deliver an annual decrease of 7.6% greenhouse gas emissions between 2020 and 2030 if we want to limit global warming to 1.5 °C [27]. We should not allow today’s crisis to compromise the efforts to tackle the world’s inescapable challenge of climate change. In addition, China had made a great progress in adjusting its energy structure. In 2019, China's coal consumptions decreased by 1.5% compared with last year. The consumptions of natural gas, hydropower, nuclear power, wind power, and other clean energy increased by 1.3%, which accounted for 23.4% of the total energy consumptions; Meanwhile, the consumptions of non-fossil energy also increased by 0.8% and accounted for 14.9% of total primary energy consumptions [12]. We should be careful to response this crisis and develop economic with no harm to both climate goals and our progress in energy structure transition.

The good news is researches already showed that a better economic growth and a better climate can be obtained simultaneously, which means economic development and CO2 emissions reductions can be coordinated [28], [29]. Moreover, there are evidences that global economic growth and fossil fuel related CO2 emissions may have begun to decouple. In 2014, the global economy increased by about 3%, but energy-related CO2 emissions remained stable [30]. Governments can use the current situation to accelerate the climate goals and launch sustainable stimulus packages focused on building a secure, clean and sustainable energy future, such as large-scale investment to boost the research and development of clean energy, advanced batteries, and energy efficiency technologies, to avoid increase too much CO2 emissions.

Specifically, for China, the country can invest the construction of “New Infrastructure” projects such as 5G networks, industrial internet, inner-city transportation and inner-city rail systems, ultra-high voltage power transmission projects, and new energy vehicle charging stations. These projects can not only create a considerable amount of new jobs to grow our economics but emit less CO2. Second, the government should insist to transition its economy from a high energy-consumption model to a low-carbon one, which is an irreversible trend and its future benefits and positive influence on other sectors could be huge. Third, government and enterprises can enlarge the proportion of investments in the research and development of new technologies to improve energy efficiency.

Affected by the coronavirus pandemic, China’s CO2 emissions would decrease in the short-term. However, the medium- and long-term effects on CO2 emissions are uncertain and the government should respond the crisis carefully to avoid extra CO2 emissions growth. The extent to which the central and local governments consider the CO2 emissions targets and the imperatives of climate change when carrying out their economic stimulus to the epidemic may affect the pathway of CO2 emissions for decades.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Qingqing Wang: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Mei Lu: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization. Zimeng Bai: Resources, Investigation, Visualization. Ke Wang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial supports from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71871022, 71471018), the Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation (161076), the Joint Development Program of Beijing Municipal Commission of Education, and the National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 97; 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200426-sitrep-97-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=d1c3e800_6.

- 2.State Statistical Bureau. Preliminary accounting results of GDP in the first quarter of 2020; 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202004/t20200417_1739602.html.

- 3.General Administration of Customs. Review of China’s Foreign Trade in the First Quarter of 2020; 2020. http://english.customs.gov.cn/Statics/83de367c-d30f-4734-aba9-2046ab9b8a19.html.

- 4.Callaway E, Cyranoski d, Mallapaty S, Stoye E, Tollefson J. The coronavirus pandemic in five powerful charts; 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00758-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Peters G.P., Marland G., Quere C.L., Boden T.A., Canadell J.G., Raupach M.R. Rapid growth in CO2 emissions after the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. Nat Clim Change. 2012;2(1):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Quéré C., Jackson R.B., Jones M.W. Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat Clim Chang. 2020;10:647–653. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-020-0797-x [Google Scholar]

- 7.IEA. Global Energy Review 2020: The impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on global energy demand and CO2 emissions; 2020. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2020.

- 8.Liu Z., et al. Near-real-time data captured record decline in global CO2 emissions due to COVID-19; 2020. https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2004/2004.13614.pdf. edited.

- 9.Shan Y., Huang Q., Guan D., Hubacek K. China CO2 emission accounts 2016–2017. Sci Data. 2020;7(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0393-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han P., Cai Q., Oda T. Assessing the recent impact of COVID-19 on carbon emissions from China using domestic economic data. Sci Total Environ. 2021:750. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myllyvirta L. Analysis: Coronavirus temporarily reduced China’s CO2 emissions by a quarter; 2020. https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-has-temporarily-reduced-chinas-co2-emissions-by-a-quarter.

- 12.State Statistical Bureau. Statistical Communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2019 National Economic and Social Development; 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202002/t20200228_1728917.html.

- 13.Statistical Bureau. Statistical Communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2018 National Economic and Social Development; 2019. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/201902/t20190228_1651335.html.

- 14.State Statistical Bureau. Industrial Production Operation in March 2020; 2020. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/202004/t20200420_1739746.html.

- 15.OPEC. World Oil Outlook 2040; 2018. https://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/WOO_2018.pdf.

- 16.EIA. International Energy Outlook 2018; 2018. https://www.eia.gov/pressroom/presentations/capuano_07242018.pdf.

- 17.BP. BP Energy Outlook – 2019 edition; 2019. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/energy-outlook/bp-energy-outlook-2019.pdf?stream=top.

- 18.Meidan M. Glimpses of China’s energy future; 2019. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Glimpses-of-Chinas-energy-future.pdf.

- 19.Gray M. Here's why China’s post-COVID-19 stimulus must reject costly coal power; 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/heres-why-china-post-covid-19-stimulus-must-turn-away-from-costly-coal-power/.

- 20.Mountford H. Responding to Coronavirus: Low-carbon Investments Can Help Economies Recover; 2020. http://redgreenandblue.org/2020/03/15/responding-coronavirus-low-carbon-investments-can-help-economies-recover/.

- 21.Lashof D. US coronavirus response: 3 principles for sustainable economic stimulus; 2020. https://www.wri.org/blog/2020/03/coronavirus-US-economic-stimulus.

- 22.Saha D. Resilience after recession: 4 ways to reboot the U.S. economy; 2020, https://redgreenandblue.org/2020/03/31/resilience-recession-four-ways-reboot-u-s-economy/.

- 23.Mi Z., Meng J., Guan D., Shan Y., Liu Z., Wang Y. Pattern changes in determinants of Chinese emissions. Environ Res Lett. 2017;12 doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa69cf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tollefson J. Climate vs coronavirus: Why massive stimulus plans could represent missed opportunities; 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00941-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Duan Y., Mu H., Li N., Li L., Xue Z. Research on comprehensive evaluation of low carbon economy development level based on AHP-entropy method: a case study of Dalian. Energy Procedia. 2016;104:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2016.12.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kretzschmar V. The fossil fuel industry is broken – will a cleaner climate be the result?; 2020. https://dnyuz.com/2020/04/01/the-fossil-fuel-industry-is-broken-will-a-cleaner-climate-be-the-result/.

- 27.UN. Emissions Gap Report 2019; 2019. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/30797/EGR2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 28.Arouri M.E.H., Youssef A.B., M'henni H., Rault C. Energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions in Middle East and North African countries. Energy Policy. 2012;45:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2012.02.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muhammad B. Energy consumption, CO2 emissions and economic growth in developed, emerging and Middle East and North Africa countries. Energy. 2019;179:232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2019.03.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Energy Agency. Energy and Climate Change: Word Energy Outlook Special Report; 2015. http://indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/WEO2015SpecialReportonEnergyandClimateChange.pdf.