Abstract

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus that it disease spreads in over the world. Coronaviruses are single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses with a genome of approximately 30 KD, the largest genome among RNA viruses. Most people infected with the COVID-19 virus will experience mild to moderate respiratory illness and recover without requiring special treatment. Older people and those with underlying medical problems like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer are more likely to develop serious illness. At this time, there are no specific vaccines or treatments for COVID-19. So, there is an emergency need for vaccines and antiviral strategies. The spike protein is the major surface protein that it uses to bind to a receptor of another protein that acts as a doorway into a human cell. The putative antigenic epitopes may prove effective as novel vaccines for eradication and combating of COV19 infection. A combination of available bioinformatics tools are used to synthesis of such peptides that are important for the development of a vaccine. In conclusion, amino acids 250–800 were selected as effective B cell epitopes, T cell epitopes, and functional exposed amino acids in order to a recombinant vaccine against coronavirus.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19, Spike protein, T and B cell epitopes prediction, Vaccine design

Highlights

-

•

Functional and Potential residues were identified in S protein.

-

•

Pocket and binding sites on the surface of S protein were detected.

-

•

B and T cell epitopes were selected and analyzed their features including mutation, toxicity, allergenicity, and antigenicity.

-

•

Selected antigenic region was analyzed based on biochemical & biophysical information.

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, a cluster of pneumonia cases, caused by a newly identified coronavirus (covid19) emerged in Wuhan, China, and approximately has spread to all of the countries in the world [[1], [2], [3]]. The outbreak of coronavirus COVID-19 has become a most challenging health emergency in over the world [4,5]. Coronaviruses is lipid-enveloped, positive-sense and single-stranded RNA viruses [6]. This virus enter cells through a two-step process: they first recognize a host-cell-surface receptor for viral attachment and then fuse viral and host membranes for entry [7]. Receptors not only determine the viral attachment step, but also play important roles in the membrane fusion process [8]. Coronaviruses can be divided into four genera: α, β, γ, and δ. For coronaviruses from all four genera, an envelope-anchored spike protein guide's coronavirus entry into host cells [9]. ACE2, found in the lower respiratory tract of humans, is known as cell receptor for SARS-CoV. The S-glycoprotein on the surface of coronavirus can attach to the receptor, ACE2 on the surface of human cells and causes membrane fusion between cells and viruses [3,10,11]. After membrane fusion, the viral genome RNA is released into the cytoplasm. The genomic RNA is used as a template to directly translate two polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, which encodes nonstructural proteins (nsps) to form the replication‐transcription complex (RTC) in a double‐membrane vesicles to replicate and synthesize a nested set of subgenomic RNAs, which encode accessory proteins and structural proteins. Lastly, the virion-containing vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane to release the virus. So, the binding of SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) glycoprotein and ACE2 receptor is a critical step for virus entry [12,13].

The number of deaths associated COVID-19 is greatly higher than the other two coronaviruses (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV), and the outbreak is still ongoing, which global concern to the public health and economics [14]. The most common symptoms of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) are fever, tiredness, and dry cough. Most people (about 80%) recover from the disease without needing special treatment [15]. But Coronavirus is considered a major threat to older people and people with pre-existing medical conditions such as asthma, diabetes, heart disease [16].

There are no specific vaccines or treatments for COVID-19 [17]. So, there is an emergency need for vaccines and antiviral strategies [18]. Infection control measures are necessary to prevent the virus from further spreading and to help control the epidemic situation and at present, it is a serious challenge. Based on this approach and given the important role of Spike (S) glycoprotein for virus entry [19]. The main aim of the current is to use of bioinformatics tool to identify potential B- and T-cell epitope(s) of S protein with high antigenicity that could be used to develop promising vaccines [20]. This paper briefly discusses and explores bioinformatics tools in vaccine design. The best antigenic region of S protein has been determined as a novel construct for vaccine. That could be used as peptide vaccines against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Sequence availability, homology search and alignment

The S protein sequence was retrieved from NCBI at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein and saved in FASTA format for further analyses; then Protein BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) against reference sequence on the database was performed using Blosum80 matrix to collect homologous sequences between different Coronaviruses. For 3D structure search, the protein sequence of S was used as an input data for the PSI-BLAST against protein data bank (PDB) at http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgito identify its homologous structures. In order to choose the best template 3D structure of protein, lower E value, higher query coverage and maximum identity was considered. The best result of PSI-BLAST was selected as template. Alignments can demonstrate the conservancy of the protein residues among various strains. T-COFFEE server at http://tcoffee.crg.cat/apps/tcoffee/do:regular [21] was used for generating of alignments. Alignments can show the conservancy of the protein residues among various strains. In this regard, the best vaccine candidates are those effective against all strains of a given pathogen. conservancy of the amino acids among viruses other than coronavirus implies probable cross-reactivity levels.

2.2. Protein topology and structure analyze

Topology prediction servers predict the transmembrane and outer membrane region of proteins. Transmembrane helix and signal peptides are not appropriate regions as B cell epitope. PRED-TMBB2 at http://www.compgen.org/tools/PRED-TMBB2 [22] was used to predict the extracellular and transmembrane regions of protein. The outside regions was also determined by TMHMM server at http://octopus.cbr.su.se/.[23].

2.3. Homology modeling

Homology modeling is the construction of an atomic model of a purpose protein based solely on the target's amino acid sequence and the experimentally determined structures of homologous proteins, referred to as templates. There are many tools and servers that are used for homology modeling. There is no single modeling program or server which is superior in every aspect to others. Since the functionality of the model depends on the quality of the generated protein 3D structure, maximizing the quality of homology modeling is crucial. Phyre2 [24] at http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index uses hidden markov model alignments through HH search to notably enhance accuracy of alignment and detection rate. To model regions with no detectable homology, phyre2 integrates a new ab initio folding simulation called Poing. The SWISS- MODEL server [25] at Error! Hyperlink reference not valid. swiss-model.expasy.org/is a fully automated protein structure homology-modeling server.

2.4. Model evaluation

GMQE (Global Model Quality Estimation) is a quality estimation which combines properties from the target–template alignment and the template search method. QMEAN, which stands for Qualitative Model Energy Analysis, is a composite scoring function describing the major geometrical aspects of protein structures. All 3D models of the protein built, were qualitatively estimated by GMQE and QMEAN scores. Qualitative evaluation of 3D models was done by ProSA at https://prosa.services.came. sbg.ac.at [26]. ProSA specifically faces the needs confronted in the authentication of protein structures acquired from X-ray analysis, NMR spectroscopy, and hypothetical estimations. Rampage [27] at http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac. uk/rapper/rampage.php was also employed for estimation of model quality using Ramachandran plot which is an algorithm for atomic level, high-resolution protein structure improvement.

2.5. Functional annotation of protein domain

InterProscan at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/about.html [28] was used to find functional analysis of protein sequences by classifying them into families and predict the presence of domains and main sites. Recognition of protein domains helps us determine functionally important domains within a protein. Antibodies against these domains could impair S functions and result in virulence reduction. Dompred at http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/dompred was employed to predict Protein domains and determine homolog domains [29].

2.6. Predicting functionally and structurally important residues

Functional conserved amino acids allow more logical thinking in the epitope prediction and protein binding surfaces. There are different servers to predict functionally and structurally important residues. In this study, InterProSurf at http://curie.utmb.edu/pattest9.html used to predict functional sites on protein surface using patch analysis [30].

2.7. Physicochemical properties of protein

Parameters such as hydrophilicity, flexibility, accessibility, turns, exposed surface, polarity and the antigenic propensity of polypeptides chains have been related to the location of B cell epitopes. So, this information about parameters has led to would allow the position of B cell epitopes to be predicted from certain features of the protein sequence. IEDB at http://tools.iedb.org/bcell/was used to predict average score of physico-chemical properties (hydrophobicity, flexibility/mobility, accessibility, polarity, exposed surface and turns) [31]. In addition, Bcepred server at http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/bcepred/.[32] was employed to predict linear B-cell epitopes in a protein sequence.

2.8. Prediction of linear and discontinue B cell Epitope

The identification of features B cell epitopes have an important role in vaccine design, immunodiagnostic tests, and antibody production. There are many tools to predict B cell epitope. Since each software uses specific algorithms and exclusive methods in epitope prediction. Therefore, the usage of several tools to predict linear B-cell epitopes in protein sequences are more reliable. Ellipro at http://tools.immuneepitope.org [33] was used to predict linear and discontinuous antibody epitopes based on a protein antigen's 3D structure. Also, in order to predict liner epitopes based on Antigenic epitopes using support vector machine to integrate tri-peptide similarity and propensity scores (SVMTriP) was employed Svmtrip server at http://sysbio.unl.edu/SVMTriP/prediction.php [34,35]. ABCpred server was used to predict linear B cell epitopes based on recurrent neural networks [36,37]. Using the VaxiJen server, the antigenicity score of all predicted B cell epitopes were identified with a score value of ≥0.4 to increase the prediction accuracy and to minimize the false positives. The sequences with a VaxiJen score ≥0.4 were selected for further analyses.

2.9. Prediction of T cell Epitope

The recognition of epitopes by T cells and the induction of immune response have a key role in the individual's immune system and Cross-strain conserved T-cell epitopes are essential for therapeutic vaccines against chronic infections. The predicted antigenic B cell epitopes were subjected to T cell epitopes prediction based on binding affinity with MHC class I and II molecules using Propred I at https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/propred1/gloss.html and Propred II at http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/propred/respectively. For propred-1 proteasome and Immuno-proteasome filters with a threshold value of 5% were kept on. ProPred I & II implements a linear prediction model and identifies epitopes that bind to MHC-I and MHC-II molecules [38]. Finally, common Epitopes that bind with both the MHC I and MHC II molecules and had antigenicity scores above 4 were selected as the best 9-mer epitope.

2.10. Eminent features profiling of selected T cells epitopes

A second screening step including their important features such as mutation, toxicity, and allergenicity which were checked by the ToxinPred server at http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/toxinpred/.[39], AllergenFP server at http://ddg-pharmfac.net/AllergenFP/.[40]. AllergenFP is generally utilized for the prediction of allergenicity of epitopes for vaccine design. In silico method, ToxinPred is used to predict Non-Toxic/Toxic peptides. For further analysis, only NonToxic epitopes were chosen.

2.11. Pocket and binding site detection

Protein-ligand binding site prediction from a 3D protein structure plays a pivotal role in rational vaccine design and can be helpful in vaccine side-effects prediction or elucidation of protein function. The Multi-scale pockets on protein surfaces were found by the GHECOM server (Grid-based HECOMi finder) at http://strcomp.protein.osaka-u.ac.jp/ghecom/.[41]. In addition, Depth (http://mspc.bii.a-star.edu.sg/tankp/help.html) was employed to calculate/predict depth, cavity sizes, ligand binding sites and PKA. Depth measures the closest distance of a residue/atom to bulk solvent [42].

2.12. Immunogenic regions selection

A region with the largest gatherings of linear and conformational B cell epitopes and most important T cell epitopes could be selected as vaccine candidates. This region should be eligible as a single-scale amino acid properties assay. Some specifications such as the amount of antigenicity, physiochemical properties average, PI and etc. should also be considered in region selection. Hence, one region was selected as suitable antigenic candidate. Other analyses were performed on the selected region to validate the selection.

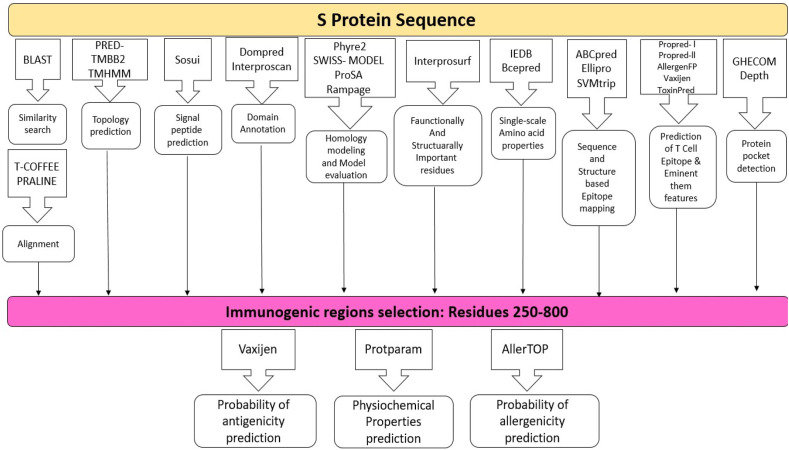

The overall workflow of vaccine design for spike protein summarized in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing an overview of the methodology pipeline.

3. Result

3.1. Protein sequencing and alignments

S protein sequence with accession No. QII57161.1 is available as a query for protein BLAST against Coronavirus producing a set of sequences containing various species of Coronaviruses. The alignments results with the high similarity were very limited, so 10 sequences with the highest similarity (identity ≥90%, query coverage: 100% and E value: 0) were selected as T-COFFEE alignment input. PSI-BLAST search against protein data bank (PDB) showed that the S protein is specific for Coronaviruses. The structure with the highest score under the PDB code of 6vsb_A (99.50% identity, 94% Query Cover) was selected as the template for homology modeling. The image of T-COFFEE alignment results with conservation color scheme is shown in Fig. 2 . PRALINE confirms T-COFEE results.

Fig. 2.

S sequence alignment with 10 sequences obtained from protein BLAST against Coronavirus. The superposition was made with the T-coffee program and adjusted manually. Residues conservancy is depicted by blue to pink colors.

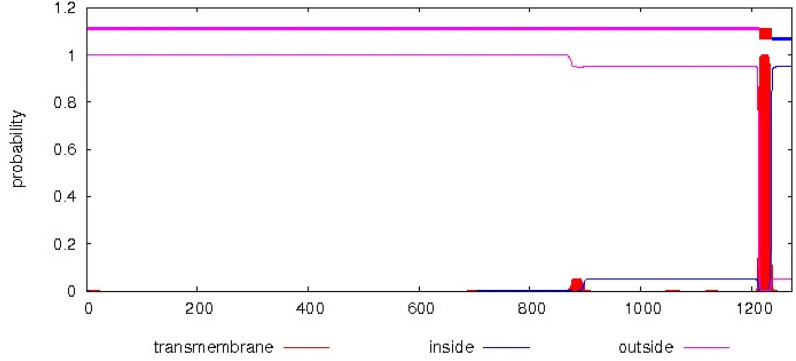

3.2. Protein topology and signal peptide prediction

Cleavage site of signal peptide was predicted between positions 18 and 19 of protein sequence by Sosui server. PRED-TMBB2 server and TMHMM identify eight transmembrane segments. The result of the 2D topology prediction of the TMHMM server is shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Topology prediction and outer membrane proteins by TMHMM server. The diagram shows the estimated preference of a particular residue to be located either on the transmembrane (red) or on the inside (blue) or outside (pink). Schematic picture shows amino acids from 18 to 700 is outside regions.

3.3. Modeling methods

Swiss model and Phyre2 softwares were recruited for homology modeling. The former prepared 4 different models with identity scores 99.26%, 76.47%, 76.47% and 79.03, and the latter introduced one model with an identity score of 78%. All of them were selected for further analyses.

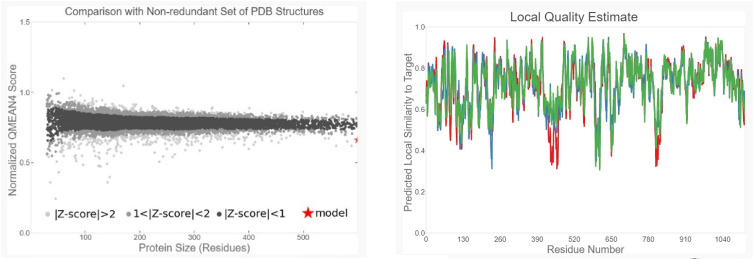

3.4. Model evaluation

QMEAN scores around zero indicate good agreement between the model structure and experimental structures of similar size. Scores of −4.0 or below are an indication of models with low quality. The resulting GMQE score is expressed as a number between zero and one, reflecting the expected accuracy of a model built with that alignment and template. Higher numbers indicate higher reliability. The best 3D model (Predicted by the Swiss model server with an identity score 99.26%) has shown GMQE and QMEAN with scores 0.72 and −2.81 respectively.

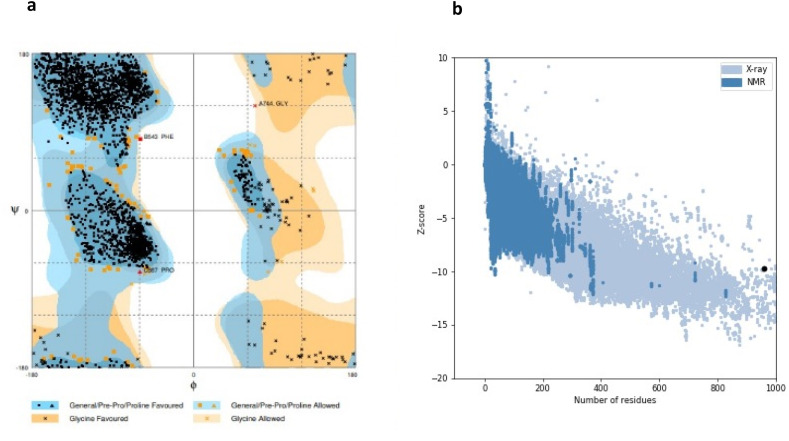

The best 3D model is shown in Fig. 4 , and model validations are shown in Fig. 5 . To tackle a number of problems including model structural distortions, plus steric clashes, unphysical phi/psi angles, and irregular hydrogen bonding (H-bonding) networks, all models were evaluated by Rampage and ProSA servers. Regarding the Ramachandran plot, 96.3% of the residues are in favored regions, and 3.5% are in allowed parts while the mere amount of 0.1% are existing in outlier regions (Fig. 6 a). ProSA revealed that the predicted model was among other acceptable proteins with z score = −9.7. (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 4.

The best model of Spike glycoprotein predicted by SWISS MODEL server.

Fig. 5.

Model validations. Both global and local estimation of the quality of the obtained model is reasonable.

Fig. 6.

Model evaluation. (a) Ramachandran plot of final S protein model. Number of residues in favored region: 2718 (96.3%). Number of residues in allowed region: 100 (3.5%). Number of residues in outlier region: 3 (0.1%). (b)- ProSA protein structure analysis results. Z score = −9.7. Overall quality of the ultimate model is acceptable.

3.5. Functional annotation of protein domain

Domain annotation shows that S protein is composed of 6 domains that their boundaries predicted at positions 163, 258, 436, 718, and 1113 of protein. According to the InterProscan server prediction, the region 16 to 1088 is non-cytoplasmic domain.

3.6. Functionally and structurally important residues

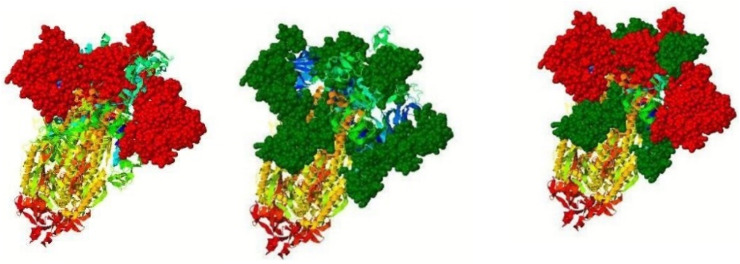

InterproSurf server annotated functional residues on the 3D structure of S protein. The results are shown in Fig. 7 . InterproSurf revealed most residues in the range of 347–500, 30–265, by auto patch analysis.

Fig. 7.

Functional residues at the protein structure surface predicted by Interprosurf. Top functional residues are highlighted in filling space model with red balls and the next top cluster highlighted in filling space model with green balls. (Color figure online).

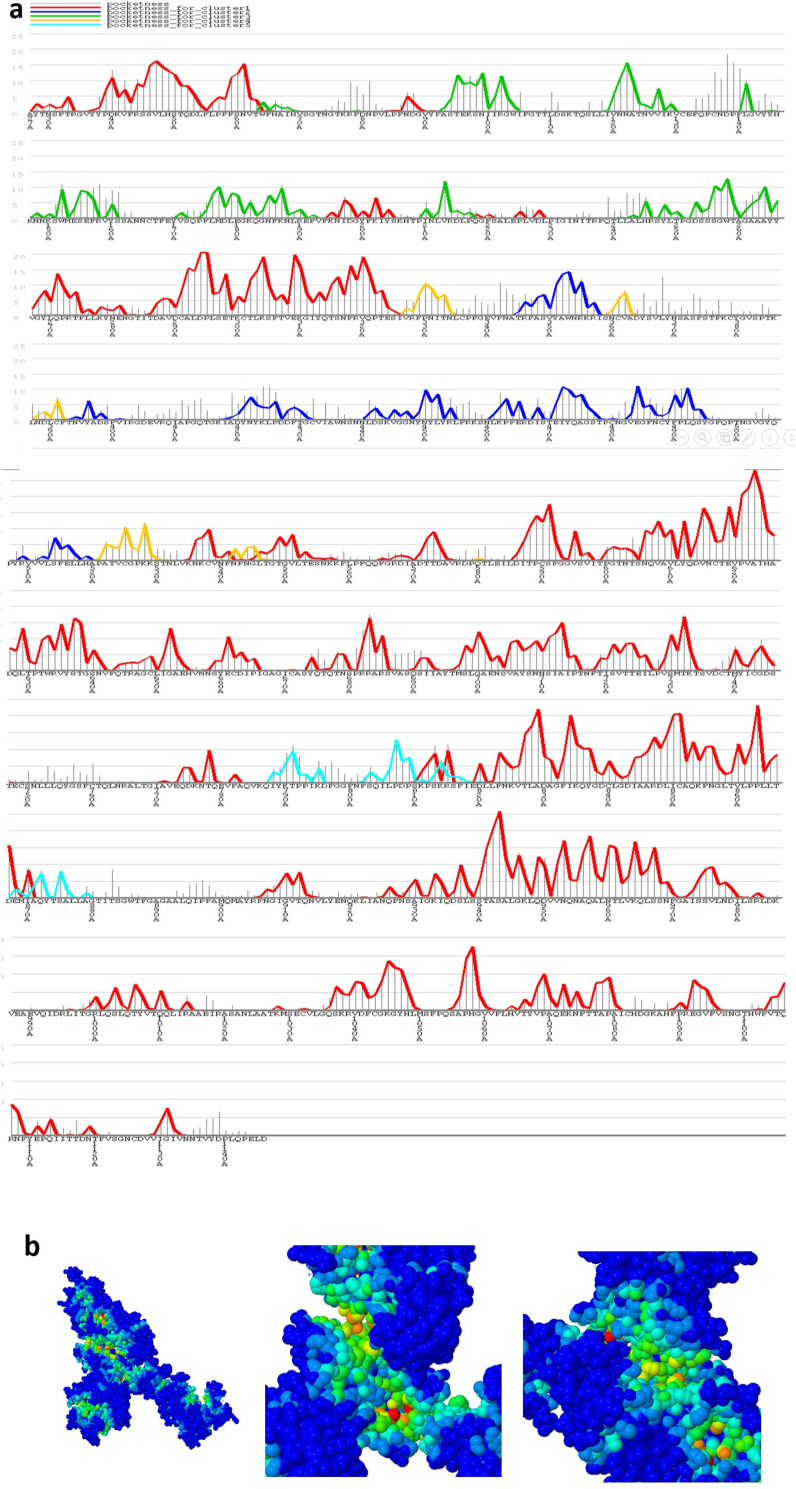

3.7. Physicochemical properties of protein

IEDB and Bcepred servers predict properties such as hydrophilicity, accessibility, antigenicity, flexibility, and beta-turn secondary structure in the protein sequence. Although single-scale amino acid properties were eligible in all sequence lengths, Based on the prediction of these two servers, the most significant regions of higher probability were located in regions 390–550,90-100, 600–690, 805–840, 1100–1110 and 1180–1200. Peaks in the plot indicate putative susceptible epitope boundaries (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

Graphical display of properties such as hydrophilicity, accessibility, antigenicity, flexibility, and beta-turn secondary structure in the protein sequence by IEDB and Bcepred servers. The regions with the highest score are shown in red and the remainders are in blue.

3.8. Linear and discontinue B cell epitope prediction

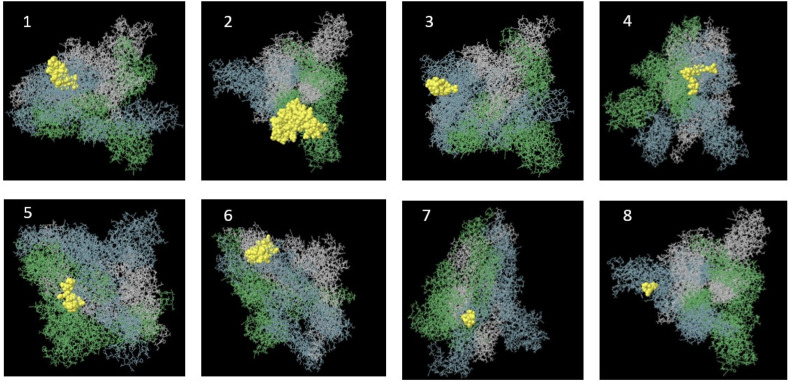

Svmtrip predicted 10 Linear B cell epitopes ranking based on the score that four of them showed the highest score. The best epitopes recommended by this server are ‘‘LNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELGK’‘, “TLVKQLSSNFGAISSVLNDI”, “QQLIRAAEIRASANLAATKM” and “KEELDKYFKNHTSPDVDLGD” at regions 1186–1205, 961–980, 1010–1029 and 1149–1168 respectively. 16 linear along with 9 discontinuous B cell epitopes were predicted by ElliPro software. The sequences and pictures of 8 linear epitopes with the highest PI (protrusion index) are shown in Fig. 9 and Table 1 . Also, the list of 4 discontinuous epitopes with the highest PI (protrusion index) is given in Table 2 .

Fig. 9.

Epitope mapping on 3D models. Discovery Studio Visualizer 2.5.5 software was used. From 1 to 8 pictures, 8 linear epitopes with the highest PI score predicted by Ellipro server are shown.

Table 1.

8 linear epitopes with the highest PI score predicted by Ellipro server.

| No | Start | End | Peptide | Number of residues | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 239 | 265 | QTLLALHRSYLTPGDSSSGWTAGAAAY | 27 | 0.84 |

| 2 | 392 | 525 | FTNVYADSFVIRGDEVRQIAPGQTGKIADYNYKLPDDFTGCVIAWNSNNLDSKVGGNYNYLYRLFRKSNLKPFERDISTEIYQAGSTPCNGVEGFNCYFPLQSYGFQPTNGVGYQPYRVVVLSFELLHAPATVC | 134 | 0.812 |

| 3 | 64 | 83 | WFHAIHVSGTNGTKRFDNPV | 20 | 0.787 |

| 4 | 64 | 83 | ENSVAYSNNSIAIPTNF | 17 | 0.708 |

| 5 | 188 | 190 | ESNKKFLPFQQ | 49 | 0.668 |

| 6 | 879 | 925 | AGTITSGWTFGAGAALQIPFAMQMAYRFNGIGVTQNVLYENQKLIAN | 47 | 0.651 |

| 7 | 577 | 584 | RDPQTLEI | 8 | 0.603 |

| 8 | 109 | 116 | TLDSKT | 6 | 0.518 |

Table 2.

4 Discontinuous epitopes with the highest PI score predicted by Ellipro server.

| No | Residues | Number of residues | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A:D1139, A:P1140, A:L1141, A:Q1142, A:P1143, A:E1144, A:L1145, A:D1146 | 8 | 0.97 |

| 2 | A:Y707, A:S708, A:N709, A:N710, A:S711, A:I712, A:A713, A:I714, A:P715, A:T716, A:N717, A:F718, A:Y1067, A:P1069, A:A1070, A:Q1071, A:E1072, A:K1073, A:N1074, A:F1075, A:T1076, A:T1077, A:A1078, A:P1079, A:A1080, A:I1081, A:C1082, A:H1083, A:D1084, A:G1085, A:K1086, A:A1087, A:H1088, A:F1089, A:P1090, A:R1091, A:E1092, A:G1093, A:V1094, A:F1095, A:V1096, A:S1097, A:N1098, A:G1099, A:T1100, A:H1101, A:W1102, A:F1103, A:V1104, A:T1105, A:Q1106, A:R1107, A:F1109, A:Y1110, A:E1111, A:P1112, A:Q1113, A:I1114, A:I1115, A:T1116, A:T1117, A:D1118, A:N1119, A:T1120, A:F1121, A:V1122, A:S1123, A:G1124, A:N1125, A:C1126, A:D1127, A:V1128, A:V1129, A:I1130, A:G1131, A:I1132, A:V1133, A:N1134, A:N1135, A:T1136, A:V1137, A:Y1138 | 82 | 0.84 |

| 3 | A:F329, A:P330, A:N331, A:I332, A:T333, A:N334, A:L335, A:C336, A:P337, A:F338, A:G339, A:E340, A:V341, A:F342, A:N343, A:A344, A:T345, A:R346, A:F347, A:A348, A:S349, A:V350, A:Y351, A:A352, A:W353, A:N354, A:R355, A:K356, A:R357, A:I358, A:S359, A:N360, A:C361, A:V362, A:A363, A:D364, A:Y365, A:S366, A:V367, A:L368, A:N370, A:S371, A:A372, A:S373, A:F374, A:S375, A:T376, A:F377, A:K378, A:Y380, A:L387, A:C391, A:F392, A:T393, A:N394, A:V395, A:Y396, A:A397, A:D398, A:S399, A:F400, A:V401, A:I402, A:R403, A:G404, A:D405, A:E406, A:V407, A:R408, A:Q409, A:I410, A:A411, A:P412, A:G413, A:Q414, A:T415, A:G416, A:K417, A:I418, A:A419, A:D420, A:Y421, A:N422, A:Y423, A:K424, A:L425, A:P426, A:D427, A:D428, A:F429, A:T430, A:G431, A:C432, A:V433, A:I434, A:A435, A:W436, A:N437, A:S438, A:N439, A:N440, A:L441, A:D442, A:S443, A:K444, A:V445, A:G446, A:G447, A:N448, A:Y449, A:N450, A:Y451, A:L452, A:Y453, A:R454, A:L455, A:F456, A:R457, A:K458, A:S459, A:N460, A:L461, A:K462, A:P463, A:F464, A:E465, A:R466, A:D467, A:I468, A:S469, A:T470, A:E471, A:I472, A:Y473, A:Q474, A:A475, A:G476, A:S477, A:T478, A:P479, A:C480, A:N481, A:G482, A:V483, A:E484, A:G485, A:F486, A:N487, A:C488, A:Y489, A:F490, A:P491, A:L492, A:Q493, A:S494, A:Y495, A:G496, A:F497, A:Q498, A:P499, A:T500, A:N501, A:G502, A:V503, A:G504, A:Y505, A:Q506, A:P507, A:Y508, A:R509, A:V510, A:V511, A:V512, A:L513, A:S514, A:F515, A:E516, A:L517, A:L518, A:H519, A:A520, A:P521, A:A522, A:T523, A:V524, A:C525, A:G526, A:P527, A:E554, A:S555, A:N556, A:K557, A:Q564, A:R577, A:D578, A:P579, A:Q580, A:T581, A:L582, A:E583, A:I584 | 201 | 0.761 |

| 4 | A:F65, A:H66, A:A67, A:I68, A:H69, A:V70, A:S71, A:G72, A:T73, A:N74, A:G75, A:T76, A:K77, A:R78, A:F79, A:D80, A:N81, A:P82, A:V83, A:L84, A:S94, A:T95, A:E96, A:K97, A:S98, A:N99, A:I100, A:I101, A:R102, A:G103, A:W104, A:I105, A:T109, A:L110, A:D111, A:S112, A:K113, A:T114, A:Q115, A:L118, A:I119, A:V120, A:N121, A:N122, A:A123, A:T124, A:N125, A:V126, A:V127, A:I128, A:K129, A:V130, A:C131, A:E132, A:F133, A:Q134, A:F135, A:C136, A:N137, A:D138, A:P139, A:F140, A:L141, A:G142, A:V143, A:Y144, A:Y145, A:H146, A:K147, A:N148, A:N149, A:K150, A:S151, A:W152, A:M153, A:E154, A:S155, A:E156, A:F157, A:R158, A:V159, A:Y160, A:S161, A:S162, A:A163, A:N164, A:N165, A:C166, A:T167, A:F168, A:E169, A:Y170, A:V171, A:S172, A:Q173, A:P174, A:F175, A:L176, A:M177, A:D178, A:L179, A:E180, A:G181, A:K182, A:Q183, A:G184, A:N185, A:F186, A:K187, A:N188, A:L189, A:R190, A:T208, A:P209, A:I210, A:N211, A:L212, A:V213, A:R214, A:D215, A:L216, A:P217, A:Q239, A:T240, A:L241, A:L242, A:A243, A:L244, A:H245, A:R246, A:S247, A:Y248, A:L249, A:T250, A:P251, A:G252, A:D253, A:S254, A:S255, A:S256, A:G257, A:W258, A:T259, A:A260, A:G261, A:A262, A:A263, A:A264, A:Y265 | 149 | 0.742 |

ABCpred result shows 40 hits of 16 meric peptide sequences as B-cell epitopes ranking based on scores. The best epitopes predicted by the server with a score above 0.85 are the sequences of “AGTITSGWTFGAGAAL”, “GVSVITPGTNTSNQVA”, “GWTAGAAAYYVGYLQP”, “PQIITTDNTFVSGNCD”, “HRSYLTPG DSSSGWTA”, “GSTPCNGVEGFNCYFP”, “TVEKGIYQTSNFRVQP”, “ESPIRATRYSYNDRME”, “GCLIG AEHVNNSYECD”, “LQSYGFQPTNGVGYQP”, “TEIYQAGSTPCNGVEG”, “TRFQTLLA LHRSYLTP”, “IGKIQDSLSSTASALG”, “FAMQMAYRFNGIGVTQ”, “SWMESEFRVYSSANNC”, “CCSCLKG CCSCGSCCK”, “TKTSVDCTMYICGDST”, and “EVRQIAPGQTGKIADY”. The predicted B cell epitopes mentioned above were identified by the Vaxijen server, and epitopes with ≥0.4 score (Table 3 ) were selected for the prediction T cell epitope.

Table 3.

Linear B-cell epitopes and T-cell epitopes of S proteins with their antigenicity scores.

| No | B-cell Epitope | Position | B cell Epitope Vaxijen score | Promiscuous T-cell Epitopes | Number of bound alleles in MHC I + MHC II | T-cell Epitope Vaxijen score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LNEVAKNLNESLIDLQELGK | 1205–1186 | 0.4281 | LNESLIDLQ | 1 + 7 | 1.0001 |

| LIDLQELGK | 8 + 14 | 0.9206 | ||||

| 2 | ITSGWTFGAGAALQIPFAMQ | 882–901 | 0.6031 | FGAGAALQI | 29 + 23 | 0.6377 |

| WTFGAGAAL | 7 + 38 | 0.4918 | ||||

| ITSGWTFGA | 27 + 9 | 0.4577 | ||||

| 3 | QSIIAYTMSLGAENSVAYSN | 690–709 | 0.5222 | YTMSLGAEN | 11 + 6 | 0.9735 |

| LGAENSVAY | 3 + 14 | 0.4173 | ||||

| YTMSLGAEN | 11 + 6 | 0.9735 | ||||

| 4 | GVSVITPGTNTSNQVA | 639–654 | 0.4651 | VSVITPGTN | 18 + 6 | 0.5501 |

| 5 | GWTAGAAAYYVGYLQP | 302–316 | 0.6210 | WTAGAAAYY | 25 + 1 | 0.6306 |

| 6 | HRSYLTPGDSSSGWTA | 290–305 | 0.6017 | LTPGDSSSG | 9 + 4 | 0.7579 |

| YLTPGDSSS | 27 + 1 | 0.5905 | ||||

| 7 | TVEKGIYQTSNFRVQP | 352–367 | 0.6733 | YQTSNFRVQ | 8 + 9 | 0.7821 |

| 8 | ESPIRATRYSYNDRME | 22–37 | 1.0078 | IRATRYSYN | 10 + 8 | 1.5237 |

| 9 | GCLIGAEHVNNSYECD | 693–654 | 0.8480 | IGAEHVNNS | 20 + 29 | 1.2611 |

| LIGAEHVNN | 9 + 6 | 0.9246 | ||||

| 10 | LQSYGFQPTNGVGYQP | 537–552 | 0.5258 | YGFQPTNGV | 39 + 33 | 1.0509 |

| LQSYGFQPT | 37 + 4 | 0.7917 | ||||

| 11 | TRFQTLLALHRSYLTP | 281–296 | 0.5115 | LLALHRSYL | 39 + 33 | 0.5241 |

| 12 | FAMQMAYRFNGIGVTQ | 943–958 | 1.3096 | FAMQMAYRF | 36 + 8 | 1.0278 |

| MQMAYRFNG | 11 + 28 | 0.4868 | ||||

| YRFNGIGVT | 15 + 12 | 1.7692 | ||||

| 13 | EVRQIAPGQTGKIADY | 451–466 | 1.3837 | VRQIAPGQT | 13 + 39 | 0.8675 |

| 14 | QTLLALHRSYLTPGDSSSGWTAGAAAY | 239–265 | 0.4822 | LLALHRSYL | 34 + 40 | 0.5241 |

| LHRSYLTPG | 1 + 10 | 0.7761 | ||||

| YLTPGDSSS | 7 + 2 | 0.5905 | ||||

| 15 | FTNVYADSFVIRGDEVRQIAPGQTGKIADYNYKLPDDFTGCVIAWNSNNLDSKVGGNYNYLYRLFRKSNLKPFERDISTEIYQAGSTPCNGVEGFNCYFPLQSYGFQPTNGVGYQPYRVVVLSFELLHAPATVC | 392–525 | 0.4563 | FELLHAPAT | 5 + 13 | 0.5409 |

| YFPLQSYGF | 2 + 23 | 0.5107 | ||||

| YGFQPTNGV | 8 + 33 | 1.0509 | ||||

| YQPYRVVVL | 8 + 32 | 0.5964 | ||||

| VVVLSFELL | 8 + 15 | 1.0909 | ||||

| VRQIAPGQT | 2 + 26 | 0.8675 | ||||

| 16 | WFHAIHVSGTNGTKRFDNPV | 64–83 | 0.4100 | FHAIHVSGT | 15 + 39 | 0.9305 |

| IHVSGTNGT | 11 + 30 | 0.8621 | ||||

| 17 | ENSVAYSNNSIAIPTNF | 702–718 | 0.4481 | VAYSNNSIA | 27 + 20 | 0.8537 |

| YSNNSIAIP | 4 + 5 | 0.5477 | ||||

| 18 | AGTITSGWTFGAGAALQIPFAMQMAYRFNGIGVTQNVLYENQKLIAN | 879–925 | 0.5747 | FAMQMAYRF | 8 + 18 | 1.0278 |

| FGAGAALQI | 9 + 7 | 0.6377 | ||||

| WTFGAGAAL | 22 + 1 | 0.4918 | ||||

| MQMAYRFNG | 0 + 40 | 0.4868 |

3.9. Prediction of T cell Epitope and Eminent features profiling of selected T cells epitopes

The B-cell epitopes with ≥0.4 Vaxijen scores were further chosen to predict T-cell epitopes. From these selected B-cell epitopes, promiscuous T-cell epitopes having the potential to bind with both MHC class I and II molecules were predicted and T-cell epitopes having a Vaxijen score of ≥0.4 were listed (Table 3).

After finalizing the common epitopes of both MHC class-1 and MHC class-II alleles, their important features including mutation, toxicity, allergenicity, and antigenicity Checked (Table 4 ). The result of T cell epitopes prediction by ToxinPred server and AllergenFP server is shown in Table 4 the sequences of WTAGAAAYY, IGAEHVNNS, LLALHRSYL, LLALHRSYL, YQPYRVVVL, VAYSNNSIA, and YSNNSIAIP as the epitopes of T cells that interact with MHC Class-II alleles and MHC Class-I alleles were considered as the most important epitopes due to features of Non-Allergen, non-toxin and high score in antigenicity.

Table 4.

Common epitopes of both MHC class-1 and MHC class-II alleles with their mutation, toxicity, and allergenicity.

| No | T-cell epitope sequences | T-cell epitope coordinates | ToxinPred | Allergen prediction | Mutation position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LNESLIDLQ | 1212–1220 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 2 | LIDLQELGK | 1216–1224 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 3 | FGAGAALQI | 888–896 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 4 | WTFGAGAAL | 886–894 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 5 | ITSGWTFGA | 882–890 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 6 | YTMSLGAEN | 595–603 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 7 | LGAENSVAY | 699–707 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 8 | VSVITPGTN | 640–648 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 9 | WTAGAAAYY | 303–311 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 10 | LTPGDSSSG | 295–303 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 11 | YLTPGDSSS | 294–303 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 12 | YQTSNFRVQ | 358–366 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 13 | IRATRYSYN | 25–33 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 14 | IGAEHVNNS | 696–704 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 15 | LIGAEHVNN | 695–703 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 16 | YGFQPTNGV | 540–548 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 17 | LQSYGFQPT | 537–545 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 18 | LLALHRSYL | 286–294 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 19 | FAMQMAYRF | 25–33 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 20 | MQMAYRFNG | 943–950 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 21 | YRFNGIGVT | 945–953 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 22 | VRQIAPGQT | 452–460 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 23 | LLALHRSYL | 241–249 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 24 | LHRSYLTPG | 245–253 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 25 | YLTPGDSSS | 249–257 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 26 | FELLHAPAT | 515–523 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 27 | YFPLQSYGF | 487–495 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 28 | YGFQPTNGV | 493–501 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 29 | YQPYRVVVL | 504–512 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 30 | VVVLSFELL | 510–518 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 31 | VRQIAPGQT | 407–415 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 32 | FHAIHVSGT | 949–957 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 33 | IHVSGTNGT | 65 + 73 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 34 | VAYSNNSIA | 405–413 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 35 | YSNNSIAIP | 407–415 | Non-Toxin | No Allergen | No Mutation |

| 36 | FGAGAALQI | 68–76 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 37 | WTFGAGAAL | 886–897 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

| 38 | MQMAYRFNG | 900–909 | Non-Toxin | Allergen | No Mutation |

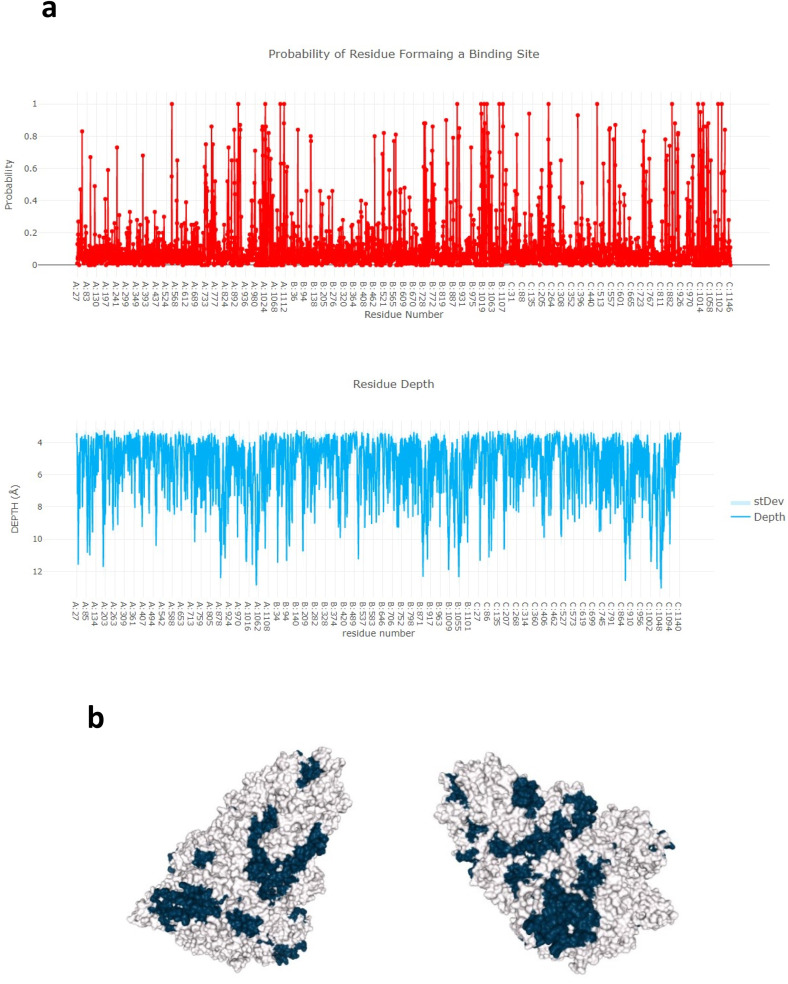

3.10. Protein pocket detection

GHECOM server showed 23 pockets on protein surfaces using mathematical morphology. A residue in a deeper and larger pocket has a greater chance to be a true pocket. The pockets of small-molecule binding sites and active sites were higher than the average value; specifically, the values for the active sites were much higher in regions 170–195, 290–320 and 940–970. This suggests that pockets contribute to the formation of binding sites and active sites of protein. GHECOM results are shown in Fig. 10 a & b.

Fig. 10.

Pocket detection of S protein by GHECOM server. (a) Graph residue-based pocketness. The height of the bar shows the value of pocketness [%] for each residue. The color of pocketness bar indicates cluster number of pocket (red: cluster 1, blue: cluster 2, green: cluster 3, yellow: cluster 4, cyan: cluster 5). (b) Jmol view of pocket structure based on pocketness color.

The potential binding sites (PBS) of proteins are part of residue or pocket which binds to ligands directly on the protein surface, they are near to the ligand-binding sites. A binding cavity is a protein sub-structure of conserved geometrical and chemical properties complementary to its bound ligand. The algorithm estimates the probability value of the form-ing part of a binding cavity for every residue of the protein. The plot shows both mean and standard deviation of depth values. The probability of residue forming a binding site, residue depth plot, and a 3D rendition of the cavity prediction is shown in Fig. 11 a & b.

Fig. 11.

Prediction of Probability of resi-due forming a binding site and residue depth plot and a 3D rendition of the cavity by depth server. (a) Probability of residue forming a binding site and residue depth plot. (b) A 3D rendition of the cavity prediction is shown using Jmol. Residues of the predicted bind-ing cavity are colored black and the rest of the protein is colored white.

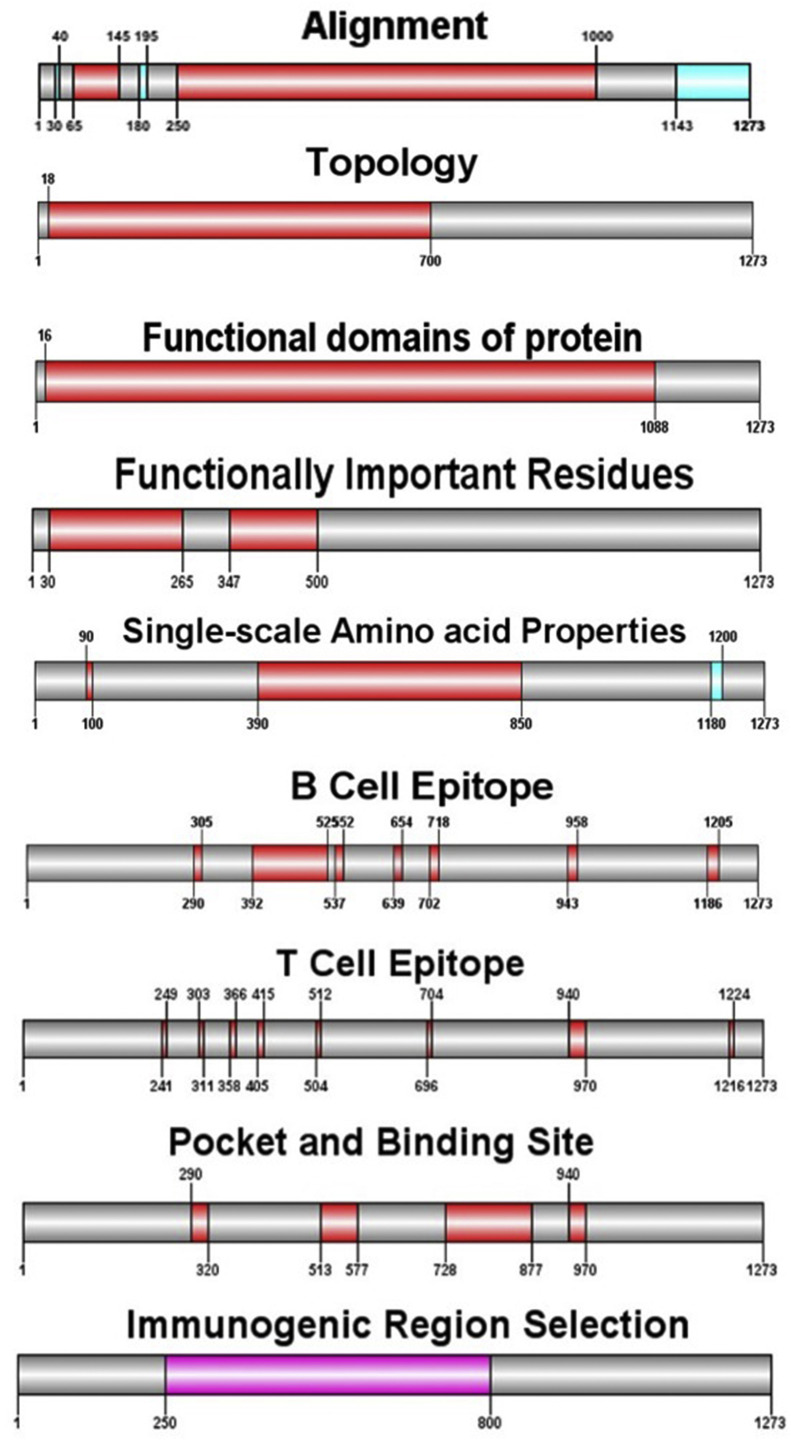

3.11. Immunogenic region selection

One region covering residues 250–800 was selected as the best region to vaccine candidate by various methodologies and softwares (Fig. 12 ). Several properties such as Vaxijen antigenicity score, PI, solubility have been correlated with the location of continuous epitopes. All results for the candidate region and S protein were summarized in Table 5 . Properties mentioned have led to a search for empirical rules that would allow the position of continuous epitopes to be predicted from certain features of the protein sequence.

Fig. 12.

Graphical display of immunogenic regions predicted by various methods and parameters. The region with the highest score are shown in red and the remainders are in blue. The consensus predictions of more or all servers shown in violet.

Table 5.

Average physicochemical properties of vaccine candidate and S protein.

| Candidate Number | Number of amino acids | Weight | Vaxigen Antigenicity Score | Allergen prediction | Instability index | Hydropathicity | Isoelectric PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 550 | 60488.03 | 0.5574 | NON-ALLERGEN | 27.80 | −0.179 | 6.04 |

| S | 1273 | 141178.47 | 0.4646 | NON-ALLERGEN | 33.01 | −0.079 | 6.24 |

4. Discussion

About 70% of the Emergence of new viral diseases that infected humans originate from animals and CoVs are among the forefronts of these pathogens [4]. The recently emerged SARS-CoV-2 infects humans and causes severe pneumonia and even in many cases, it is deadly [43,44]. In December 2019, After first identified in Wuhan, Hubei province of China, it became the center of an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown cause, which raised intense attention not only within China but internationally. At present, this virus has spread to 205 countries [45,46]. All the world facing a serious health threat due to SARS-CoV-2 virus, and there is an urgent need for corresponding therapies and preventative measures. At present, there are no reliable, specific drugs against 2019- nCoV infection available on the market [15].

Medical biotechnology is playing a considerable role in the development of recombinant vaccines against infectious viruses and bacteria. computer-based immune-informatics can be effective for analysis of immunogenic data and vaccine development and this approach can decline time and cost [47]. The epitope-based vaccines can enhance immune responses by only selecting the antigenic parts of proteins exposed on the surface. Thus, the employment of bioinformatics tools to select the appropriate region as a vaccine candidate seems logical [41,48]. Some of these designed vaccine candidates validate with experimental analyses. In vivo analyses confirmed in silico predictions [[49], [50], [51]].

The spike protein on the surface of the viral particle plays key roles in the binding of the cell receptor and membrane fusion, by which the host range is firmly determined. ACE2, found in the lower respiratory tract of humans, is known as cell receptor for SARS-CoV [52].

Vaccine developed based on S protein could be effective against SARS-CoV-2 [[53], [54], [55]]. Alignment of sequences from different strains suggests that such vaccine could trigger antibodies with complete specificity for SARS-CoV-2. The physiochemical properties of S protein computed via protparam demonstrates that it contained 1273 amino acids (aa) with molecular weight of 141178.47 kDa. Theoretical isoelectric point (PI) of subject proteinwas 6.24 which indicate its negative in nature. An isoelectricpoint under 7 shows negatively charged protein. Acidic nature of S as well as its localization are stimulating for B-cell responses [56,57]. The proteins with membrane localization have one or more transmembrane helices that cannot be detected by the B-cells and T-cells. They only recognize foreign antigens that are displayed on the surfaces of the body's own cells. Further, the signal sequence is a temporary part of mature proteins [58]. So, the signal peptide is not an appropriate region for vaccine design. Topology predictions showed that 18 amino acids at the N-terminus of the protein were predicted as signal peptide. This region could not be exposed and appropriate to participate in B cell & T cell epitopes.

Building a homology model comprises four main steps: identification of the template, alignment, model building, and quality evaluation. These steps have been repeated until a satisfactory model was achieved using the SWISS MODEL. The 3D models estimated qualitatively by two servers revealed that there was a consensus on a single model. QMEAN is a composite scoring function for the estimation of the global and local model quality. The score of a model is also shown in relation to a set of high-resolution PDB structures (Z-score).

InterProSurf server prediction shows that most of the functional amino acids are located in the selected region. Therefore, it could be concluded that this region is the most significant functional site of the protein. Thus, antibodies raised against these domains could the best area for vaccine design. B-cell epitopes have different features that we can recognize the degree of importance and potential of B-cell epitopes based on them [59]. To reduce fluctuations, the score for each target amino acid residue in a query sequence is computed as the average of the propensity values of the amino acids in a sliding window centered at the target residue. Hydrophilicity, accessibility, antigenicity, flexibility, and secondary structure properties have a basic role in B cell epitope prediction [32]. According to the prediction of Single-scale Amino acid properties by the IEDB server, 2 regions including 390–550 and 600–690 that located in the selected region had a high score. Relying on just one of these properties, reliable results could not be achieved. Amino acid pair (AAP) antigenicity scale is based on the finding that B-cell epitopes favor particular AAPs. Using SVM classifier, the AAP antigenicity scale approach has much better performance than the scales based on the single amino acid propensity. So, we composed all the data from diverse servers to predict the best B cell epitopes [59]. These epitopes can be classified into two types: linear and discontinue epitopes. Amino acid sequences that are linear in shape are called Continuous epitopes (Liner) while discontinuous epitopes refer to amino acid sequences that have a folded conformation. Linear and discontinuous epitopes in S protein were predicted by various software and various algorithms to achieve consensus epitopes. Consensus epitopes obtained from various algorithms are more reliable for selection. According to the predictions of the Svmtrip, ABCpred, Ellipro, and the antigenic scores belonging to them, the best B cell epitopes were in 1205–1186, 690–709, 290–305, 352–364, 693–654, 537–552, 451–466 and 870–925 regions. Most of these areas were located within the selected region.

The B-cell epitopes that exhibited antigenic potential above the threshold score were analyzed for the identification of T-cell epitopes. Adaptive immunity is mediated by the recognition of peptide antigens (T-cell epitopes) bound to MHC molecules. In our study, 9-mer T-cell epitopes were predicted from the antigenic B-cell epitope with the tools Propred I and Propred II. MHC-I and MHC-II epitopes interact with numerous HLA alleles and are highly antigenic in nature. In the next step, the selected best T cell epitopes which were common in binding to MHC-I and MHC-II checked for mutation, toxicity, allergenicity, and antigenicity. Many of them had allergenic properties, so they were not a good choice for vaccine design. The best T cell epitopes in terms of the characteristics mentioned were LIDLQELGK, WTAGAAAYY, YQTSNFRVQ, IGAEHVNNS, LLALHRSYL, YRFNGIGVT, LLALHRSYL, YQPYRVVVL, VAYSNNSIA, and YSNNSIAIP (MHC-I & MHC-II) at positions 1216–1224, 303–311, 358–366, 696–704, 286–294, 945–953, 241–249, 504–512, 405–413, and 407–415. Eighty percent of the predicted T cell epitopes were in the selected area, indicating that the area could be effective to induce T cell responses. Finally, the Depth server result shows that a higher possibility of residue forming a binding site is located in regions 728–887, 246–396, 513–577 and 1109–1112.

All these analyses reveal that majorities, as well as the best B cell epitopes and T cell epitopes, are located in 250–800 region. So, this region was selected as a vaccine candidate. The average of each single scale amino acid propensity was increased in the candidate vaccines than their parent protein, S. The predicted epitopes should be tested for therapeutic potency in future studies. In the present study, a bioinformatics analysis identify surface-exposed peptides, rather than focus on the whole pathogen, which is more efficient. We predict and suggest that the supposed epitopes may have a vaccine potential with excellent scope. Our bioinformatics analysis identified potential strong T- and B-cell epitopes that may assist the development of potent peptide-based vaccines against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. This study can help o control this growing health threat.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

As the present study involved no experimental with animals or human, hence there was no need for approval by the Ethics Committee of Yazd University.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maryam Tohidinia: Project administration, Writing - original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology. Fatemeh Sefid: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have received no financial support for the elaboration of this manuscript. Yazd University did not play any decision-making role in the study analysis or writing of the manuscript. All authors declare no Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.Yang L., Lei Y., Zhang R., Liu J., Liu Q., Li M. A Descriptive Study; China: 2020. Epidemiological and Clinical Features of 200 Hospitalized Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 in Yichang. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck M., Tobin Djtophj. 2020. The 2019/2020 Novel Corona Virus Outbreak: an International Health Management Perspective; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalita P., Padhi A., Zhang K.Y., Tripathi T.J.M.P. 2020. Design of a Peptide-Based Subunit Vaccine against Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2; p. 104236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma X.-L., Chen Z., Zhu J.-J., Shen X.-X., Wu M.-Y., Shi L.-P. 2020. Management Strategies of Neonatal Jaundice during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak; pp. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H.-W., Yu J., Xu H.-J., Lei Y., Pu Z.-H., Dai W.-C. 2020. Corona Virus International Public Health Emergencies: Implications for Radiology Management. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan Y., Schneider T., Leong M., Aravind L., Zhang DJb. 2020. Novel Immunoglobulin Domain Proteins Provide Insights into Evolution and Pathogenesis Mechanisms of SARS-Related Coronaviruses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawase M., Kataoka M., Shirato K., SJJov Matsuyama. Biochemical analysis of coronavirus spike glycoprotein conformational intermediates during membrane fusion. 2019;93:19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00785-19. e00785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walls A.C., Tortorici M.A., Xiong X., Snijder J., Frenz B., Bosch B.-J. Structural Studies of Coronavirus Fusion Proteins. 2019;25:1300–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsaadi E.A., Neuman B.W., Jones I.M.J.V. A fusion peptide in the spike protein of MERS coronavirus. 2019;11:825. doi: 10.3390/v11090825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Krüger N., Mueller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S.J.B. 2020. The Novel Coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) Uses the SARS-Coronavirus Receptor ACE2 and the Cellular Protease TMPRSS2 for Entry into Target Cells. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chowdhury R., CDJb Maranas. 2020. Biophysical Characterization of the SARS-CoV2 Spike Protein Binding with the ACE2 Receptor Explains Increased COVID-19 Pathogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia S., Yan L., Xu W., Agrawal A.S., Algaissi A., Tseng C.-T.K. A pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting the HR1 domain of human coronavirus spike. 2019;5 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Letko M.C., VJb Munster. 2020. Functional Assessment of Cell Entry and Receptor Usage for Lineage B β-coronaviruses, Including 2019-nCoV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Q., Zhao S., Gao D., Lou Y., Yang S., Musa S.S. 2020. A Conceptual Model for the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in Wuhan, China with Individual Reaction and Governmental Action. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang B., Bragazzi N.L., Li Q., Tang S., Xiao Y., Wu JJIdm. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) 2020;5:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu HJBt. Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV) 2020;14:69–71. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eyal N., Lipsitch M., Smith P.G. 2020. Human Challenge Studies to Accelerate Coronavirus Vaccine Licensure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X., Chen P., Wang J., Feng J., Zhou H., Li X. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. 2020;63:457–460. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang N., Shang J., Jiang S., Du LJFiM. Subunit vaccines against emerging pathogenic human coronaviruses. 2020;11:298. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pirovano W., Feenstra K.A., Heringa J.J.B. PRALINE™: a strategy for improved multiple alignment of transmembrane proteins. 2008;24:492–497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagos P.G., Liakopoulos T.D., Spyropoulos I.C., SJJNar Hamodrakas. PRED-TMBB: a web server for predicting the topology of β-barrel outer membrane proteins. 2004;32:W400–W404. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krogh A., Larsson B., Von Heijne G., ELJJomb Sonnhammer. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley L.A., Mezulis S., Yates C.M., Wass M.N., MJJNp Sternberg. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling. prediction and analysis. 2015;10:845. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., MCJNar Peitsch. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiederstein M., MJJNar Sippl. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W., Xia M., Chen J., Deng F., Yuan R., Zhang X. Data set for phylogenetic tree and RAMPAGE Ramachandran plot analysis of SODs in Gossypium raimondii and. G. arboreum. 2016;9:345–348. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zdobnov E.M., Apweiler R.J.B. InterProScan–an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. 2001;17:847–848. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.9.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bryson Jrjgasb, Human Geography The ‘second’global shift: the offshoring or global sourcing of corporate services and the rise of distanciated emotional labour. 2007;89:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oezguen N., Zhou B., Negi S.S., Ivanciuc O., Schein C.H., Labesse G. Comprehensive 3D-modeling of allergenic proteins and amino acid composition of potential conformational IgE epitopes. 2008;45:3740–3747. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vita R., Overton J.A., Greenbaum J.A., Ponomarenko J., Clark J.D., Cantrell J.R. The immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0. 2015;43:D405–D412. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha S., Raghava G.P.S. International Conference on Artificial Immune Systems. Springer; 2004. BcePred: prediction of continuous B-cell epitopes in antigenic sequences using physico-chemical properties; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponomarenko J., Bui H.-H., Li W., Fusseder N., Bourne P.E., Sette A. ElliPro: a new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. 2008;9:514. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao B., Zheng D., Liang S., Zhang C. Springer; Immunoinformatics: 2020. SVMTriP: A Method to Predict B-Cell Linear Antigenic Epitopes; pp. 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X., Ren Z., Sun Q., Wan X., Sun Y., Hua Y. Evaluation and comparison of newly built linear B-cell epitope prediction software from a users' perspective. 2018;13:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saha S., Raghava G.P. Springer; Immunoinformatics: 2007. Prediction Methods for B-Cell Epitopes; pp. 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salarpour A. 2016. Linear B-Cell Epitope Prediction for S1 Protein of Infectious Bronchitis Virus. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh H., Raghava G.J.B. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. 2001;17:1236–1237. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta S., Kapoor P., Chaudhary K., Gautam A., Kumar R., Raghava G.P. Computational Peptidology. Springer; 2015. Peptide toxicity prediction; pp. 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimitrov I., Naneva L., Doytchinova I., Bangov I.J.B. AllergenFP: allergenicity prediction by descriptor fingerprints. 2014;30:846–851. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tohidinia M., Moshtaghioun S.M., Sefid F., Falahati AJIJoPR . Functional Exposed Amino Acids of CarO Analysis as a Potential Vaccine Candidate in Acinetobacter Baumannii. 2019. Therapeutics; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan K.P., Nguyen T.B., Patel S., Varadarajan R., Madhusudhan MSJNar Depth: a web server to compute depth, cavity sizes, detect potential small-molecule ligand-binding cavities and predict the pKa of ionizable residues in proteins. 2013;41:W314–W321. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.CPEREJZlxbxzzZlz Novel. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. 2020;41:145. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryson-Cahn C., Duchin J., Makarewicz V.A., Kay M., Rietberg K., Napolitano N. 2020. A Novel Approach for a Novel Pathogen: Using a Home Assessment Team to Evaluate Patients for 2019 Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hui D.S., I Azhar E., Madani T.A., Ntoumi F., Kock R., Dar O. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan. China. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sohrabi C., Alsafi Z., O'Neill N., Khan M., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A. 2020. World Health Organization Declares Global Emergency: A Review of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaper J.B., Rappuoli R. CRC Press; 2004. An Overview of Biotechnology in Vaccine Development. New Generation Vaccines; pp. 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ul Qamar M.T., Saleem S., Ashfaq U.A., Bari A., Anwar F., SJJotm Alqahtani. Epitope‐based peptide vaccine design and target site depiction against Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus: an immune-informatics study. 2019;17:362. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fattahian Y., Rasooli I., Gargari S.L.M., Rahbar M.R., Astaneh S.D.A., JJMp Amani. Protection against Acinetobacter baumannii infection via its functional deprivation of biofilm associated protein (Bap) 2011;51:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Esmaeilkhani H., Rasooli I., Hashemi M., Nazarian S., FJAjomb Sefid. Immunogenicity of cork and loop domains of recombinant Baumannii acinetobactin utilization protein in murine model. 2019;11:180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sangroodi Y.H., Rasooli I., Nazarian S., Ebrahimizadeh W., FJTjoms Sefid. Immunogenicity of conserved cork and ß-barrel domains of baumannii acinetobactin utilization protein in an animal model. 2015;45:1396–1402. doi: 10.3906/sag-1407-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shang J., Wan Y., Liu C., Yount B., Gully K., Yang Y. Structure of mouse coronavirus spike protein complexed with receptor reveals mechanism for viral entry. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Y., Li J., Heck S., Lustigman S., Jiang SJJov. Antigenic and immunogenic characterization of recombinant baculovirus-expressed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein: implication for vaccine design. 2006;80:5757–5767. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00083-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen Z., Zhang L., Qin C., Ba L., Christopher E.Y., Zhang F. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus induces protective neutralizing antibodies primarily targeting the receptor binding region. 2005;79:2678–2688. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2678-2688.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Z., Post P., Chubet R., Holtz K., McPherson C., Petric M. A recombinant baculovirus-expressed S glycoprotein vaccine elicits high titers of SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) neutralizing antibodies in mice. 2006;24:3624–3631. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaladhar DJIJoPSR, Research Genomic and proteomic studies using computational approaches in. SARS Genome. 2011;7:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mallik K. 2020. Use of Isoelectric Point for Fast Identification of Anti-SARS CoV-2 Coronavirus Proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janeway C.A., Jr., Travers P., Walport M., Shlomchik M.J. Immunobiology: the Immune System in Health and Disease. fifth ed. Garland Science; 2001. Antigen recognition by T cells. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen J., Liu H., Yang J., K-CJAa Chou. Prediction of linear B-cell epitopes using amino acid pair antigenicity scale. 2007;33:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]