ABSTRACT

Reports of college students experiencing food insecurity (FI), defined as inadequate access, availability, adequacy, and stability of food, have sparked national calls for alleviation and prevention policies. However, there are a wide variety of FI rates reported across studies and even among recent literature reviews. The current scoping review aimed to develop a weighted estimated prevalence of FI among US students using a comprehensive search approach. In addition, study characteristics that may be related to the high variability in reported FI prevalence were explored. To address these aims, the peer-reviewed and gray literature on US college student FI was systematically searched to identify 12,044 nonduplicated records. A total of 51 study samples, across 62 records, met inclusion criteria and were included in the current review. The quality of the included studies was moderate, with an average rate of 6.4 on a scale of 0–10. Convenience (45%) and census (30%) sampling approaches were common; only 4 study samples were based on representative sampling strategies. FI estimates ranged from 10% to 75%. It was common for very low security to be as prevalent as, or more prevalent than, low food security. The surveying protocols used in the studies were related to the FI estimates. The USDA Short Form Food Security Survey Module (FSSM; 50%) and the USDA Adult FSSM (40%) prevalence estimates were larger than for the full USDA Household FSSM (13%). When these surveys referenced a 12-mo period, FI estimates were 31%. This was a lower FI estimate than surveys using reference periods of 9 mo or shorter (47%). The results indicate that FI is a pressing issue among college students, but the variation in prevalence produced by differing surveys suggests that students may be misclassified with current surveying methods. Psychometric testing of these surveys when used with college students is warranted.

Keywords: food insecurity, food security, hunger, university students, college students, systematic review

Introduction

Food insecurity (FI) is the limited or uncertain access to sufficient nutritious food. An estimated 11.8% of American households experienced FI during 2017 (1). Adults experiencing FI are more likely to have low-quality dietary patterns (2–4). Ultimately, experiences of FI are associated with diminished mental and physical health (5–10). Allowing FI to persist in the United States compromises the quality of life and widens health disparities for millions of Americans.

A recent growing concern is the high reported prevalence of FI among postsecondary students (11), with some studies reporting more than half of students are food insecure. Numerous peer-reviewed articles, online reports, and news pieces have elicited concern for US college students facing hunger. These reports have been met with calls to address these issues with policies and programs, such as campus food pantries or financial aid modifications (12). As US colleges and universities begin to enroll a diversity of students with varying sociocultural backgrounds, changes to better support students, and their respective concerns, become essential.

Although the high FI prevalence rates are used as evidence that policy interventions are needed, the synthesis and analysis of the growing body of literature has been limited. There have been 3 recent reviews, each limited in scope or practical applications for the field. A seminal review by Bruening et al. (13) provided a narrative review of studies and produced the estimated prevalence of FI affecting one-third of college students, which is commonly referred to in the popular press. However, this estimate was unweighted across studies, thus not considering the size of each study, and the inclusion of studies from outside of the United States limited its specificity. A second review from Nazmi et al. (14) provided a review of exclusively US studies. Nazmi et al. (14) calculated a weighted prevalence estimate much higher than that produced in the original review, with an estimated 47.2% of students experiencing FI. Although Nazmi et al. (14) provided a weighted US-specific estimate, it was lacking in 2 critical areas. Firstly, fewer studies were included in this later review than were US-based and originally identified in Bruening et al. (13). This was counterintuitive, given the later date of the work, and indicated that many studies may have been overlooked. Secondly, Nazmi et al. (14) suggest that lower-quality studies may result in underestimations of college FI but a formal analysis of the quality of the synthesized literature was not conducted. Finally, the Government Accountability Office recently published a governmental narrative literature review (12). This report was the most recent review in this area and advanced the field by evaluating FI alleviation efforts. However, given the intended nonspecialist audience, the search strategies and quality criteria were not described in depth. Although these reviews presented descriptive overviews of the field, their shortcomings warranted a new systematic scoping approach to evaluate the prevalence of FI among US college students.

The aims of the current scoping review focus on producing a weighted estimated prevalence of FI among US students and describing how study characteristics relate to this estimate. The 3 primary questions for the current scoping review are as follows: 1) What is the prevalence of FI among students at community colleges and 4-y universities in the United States? 2) What is the quality of the studies that these estimates are based on? 3) What study characteristics are related to FI prevalence estimates?

Methods

All procedures for the scoping review were conducted based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (15) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (16). The protocol for the review was registered on 10 July, 2017 and is publicly available on the PROSPERO register (CRD42017069902) (17).

Four databases were used for the initial identification of articles: 1) PubMed/Medline; 2) EBSCO Host, Academic Search Complete; 3) Web of Science; and 4) ProQuest. In each database, every combination of the following keywords was used: (Food insecur* OR Food secur* OR Food insufficien* OR Hunger OR Food access) and (University student* OR College student*). To identify “gray literature” (unpublished reports of studies), theses/dissertations were included in the ProQuest database and authors of relevant studies were asked for additional unpublished results or suggested citations. To extend the comprehensiveness of searches, citations selected for full-text review were also used for a reference list search (backward reference search) and cited reference search (forward reference search). All database searches, reference searches, and author communications were conducted and logged between June 2017 and June 2018.

Study eligibility criteria

Title and abstract results from the systematic searches were independently screened by 2 researchers. To be eligible for inclusion, studies must have 1) collected data and/or been published after 1995 (when FI terminology became consistent in the United States); 2) been written in English; 3) reported quantitative categorical outcomes of US university students related to FI; 4) indicated the method for evaluating FI; and 5) provided no intervention or provided baseline characteristics before an intervention. This initial screen resulted in exclusion or consideration for further full-text review. The full texts of all citations considered for further review were, again, screened independently by 2 researchers based on the aforementioned criteria. For articles that did not indicate the year of data collection, these data were assumed to be collected after 1995 if the articles were published after the year 2000.

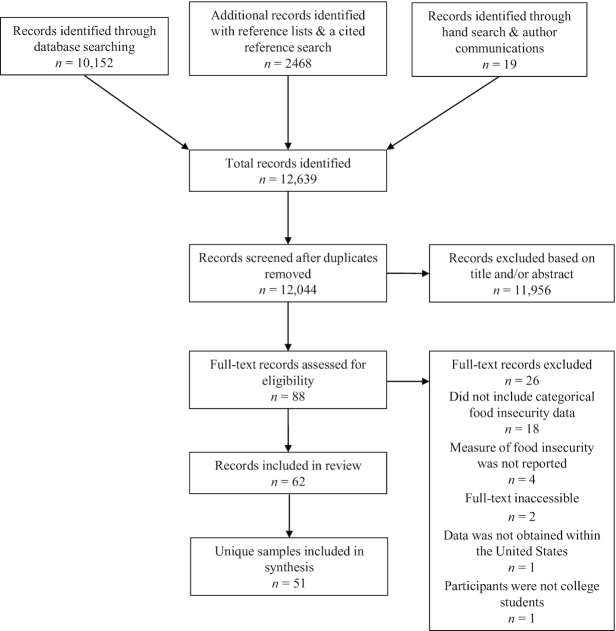

Records were reviewed and organized to represent individual study samples. Sixty-two records reported on studies that met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). When publications reported on multiple studies or reported unique results (including sociodemographic characteristics and FI estimates) for 2-y and 4-y students, the records were split to represent their distinct samples. One publication included data from 4 studies (18) and 1 report presented results for 2-y and 4-y student samples separately (19), raising the total to 66 studies. After this, when separate records reported on the same study, the record published later was included in the final analyses. If details were given in the initial record but omitted in the later record, those were used to supplement the study details and subsequent description. Fifteen records were identified as earlier or preliminary publications—presentation abstracts, gray reports, etc.—that had later corresponding publications identified in the search (20–34). These records were used to provide supplemental information to describe the studies’ methodology, with results reported in the later publications (18, 35–42) used for analyses. After accounting for the overlap in those records, a total of 51 distinct samples were identified. For reporting purposes, studies were organized chronologically by the year of the latest citation affiliated with each study sample and then alphabetized by the first author's last name within each year.

FIGURE 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from each study by CJN and independently checked for accuracy by 1 other researcher. Discrepancies were reconciled by CJN, BE, and SMN-R. Using a standardized form, extracted characteristics included authors, publication year, gray literature or peer-reviewed source, year/month of data collection, study design, study population, sampling and recruitment strategies, sample size, sample demographics, size and location of university, FI measurement tool, FI reference period, medium (online, in-person, etc.) of FI assessment, prevalence of FI, relations of correlates to FI, and statistical methods. Unless otherwise stated, students who participated in each study were assumed to be enrolled at the institution reported as granting human subjects research approval. When >1 article reported on the same set of data, information was extracted from all reports; if information was inconsistent, the later publication was assumed to be the final analysis and superseded earlier reports.

Quality assessment

The quality of each study described in a full article, report, or book was evaluated on 5 criteria based on a scale used previously (43) that is grounded in the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (44). The 5 criteria used to assess the quality were 1) an a priori aim/hypothesis; 2) a specific study population; 3) rigorous participant recruitment; 4) sufficient sample reporting; and 5) reliable and valid measures of FI. Each criterion was weighted equally and evaluated on a scale of 0–2, where unmet/unmentioned responses = 0, partially met responses = 1, and completely met responses = 2; the criteria and scoring are presented in Table 1. When all criteria were evaluated, a total score ranging from 0–10 was obtained. When >1 article reported on the same study, the quality criteria information provided in both reports was aggregated. This process was conducted by 2 independent researchers, with discrepancies discussed before formalizing the score. The quality of included abstracts, if not followed by a lengthier report, was not evaluated owing to insufficient information to score each criterion. Quality assessments for each included study were evaluated to describe the overall strength of the evidence reviewed but were not used as inclusion criteria.

TABLE 1.

Study quality assessment criteria and coding schema1

| Criteria | Unmet/unmentioned responses (score = 0) | Partially met responses (score = 1) | Completely met responses (score = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A priori aim/hypothesis specific to food insecurity | No mention of aim/hypothesis | Implications of food insecurity in aim/hypothesis (i.e., hunger or difficulty affording food) | Explicit mention of food insecurity in aim/hypothesis |

| Study population clearly specified and defined | No mention of the population the sample is meant to represent | Population partially and/broadly defined | Population clearly defined |

| Rigorous participant recruitment | Convenience sampling techniques | N/A | Random sample or census |

| Sufficient sample reporting | No report of response rate or nonresponse bias evaluations | Report response rate or nonresponse bias evaluations | Report response rate and nonresponse bias evaluations |

| Reliable and valid measures of food insecurity | Measures without psychometric testing | Measures with limited testing or tested in different population | Measures with psychometric testing in related population |

Synthesis

To provide an overview of the literature, percentages and medians (given the skewedness of the data) of study and sample characteristics are shown. Quality assessment criteria were descriptively analyzed and compared with other study characteristics. FI prevalence estimates were calculated using weighted means from study estimates and study sample size in Excel 16.0 for Office 365 (Microsoft). Weighted FI prevalence estimates were compared with other study characteristics (i.e., surveying protocols and institutional setting).

Results

Study characteristics

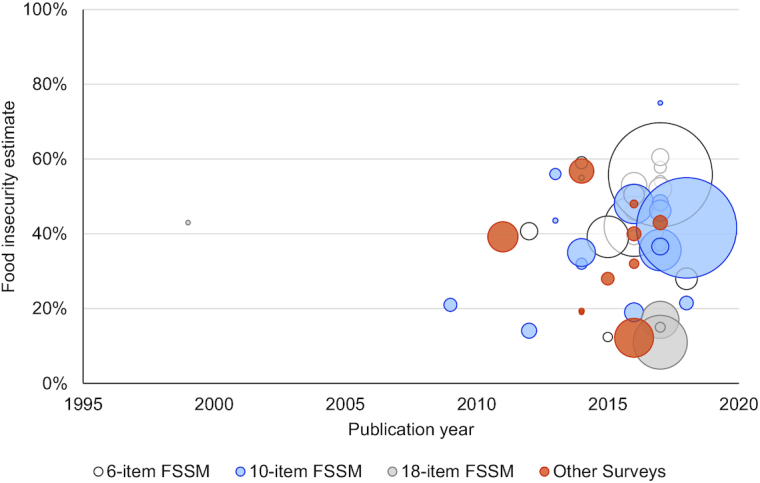

Basic characteristics of the included studies are outlined in Table 2. Although the review included reports published after 1995, most records were published in 2016 or later. Figure 2 demonstrates this recent proliferation of studies by displaying each study alongside its final publication year, sample size, and FI estimate. Over half of the studies were published as peer-reviewed articles, but a considerable second group of studies were reported through gray literature as online reports and academic theses or dissertations. The majority (96%) of studies included in this review were cross-sectional, with only 2 records reporting results of longitudinal designs. Sample sizes ranged from 49 to 26,131 participants with a median of 514/study.

TABLE 2.

Basic characteristics of the studies examining US college student food insecurity1

| Authors (Ref) and reference types | Study design (sampling strategy) | Study population | Sample size (response rate, %) | Demographics | University setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khachadourian (45), thesis | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Re-entry (>25 y ) female students | 49 (49) | Sex: 100% femaleAge: 49% 36–45 yRace/ethnicity: 41% white, 32% Income: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | California State University, Fresno |

| Chaparro et al. (46), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (random, stratified by classes) | Nonfreshmen undergraduate and graduate students | 410 (33, instructors; 99, students) | Sex: 56% femaleAge: 26 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 26% white, 43% AsianIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: 69% born in the United States | University of Hawai'i at Mānoa |

| Freudenberg et al. (47), report | Cross-sectional (stratified representative sample) | Undergraduate students | 2200 (16) | Sex: 59% femaleAge: 66% 18–24 yRace/ethnicity: 20% white, 30% Hispanic Income: 54% received ≤$49,999/yEmployment: NR‡Fin. aid: NR‡Nationality: 58% born in the United States | 17 community college and 4-y universities (City University of New York) |

| Magoc (48), thesis | Cross-sectional (census) | College students | 708 (NR) | Sex: 78% femaleAge: 23.8 ± 7.9 y (mean ± SD) Race/ethnicity: 87% whiteIncome: NR Employment: 57% employedFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Eastern Illinois University |

| Gonzales (49), thesis | Cross-sectional (random course selection) | Undergraduate students | 62 (NC‡) | Sex: NRAge: ranged from 19 to ≥25 y‡Race/ethnicity: NRIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | University of Northern Colorado |

| Gaines et al. (20; 35), conference abstract; peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (convenience and stratified random) | Nonfreshmen undergraduate students, 19–25 y old | 557 (87 within classrooms) | Sex: 76% femaleAge: ranged from 19–25 y‡Race/ethnicity: 82% whiteIncome: 72% received ≤$20,000/y Employment: NR‡Fin. aid: 44% received aidNationality: NC‡ | University of Alabama |

| Gorman (50), thesis | Cross-sectional (convenience) | College students, 18–26 y old without spouses or children | 298 (NR) | Sex: NRAge: 18–26 y NRRace/ethnicity: NRIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Kent State University |

| Hanna (51), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (convenience) | College students | 67 (NC‡) | Sex: 61% femaleAge: 77% 18–24 yRace/ethnicity: 34% white, 30% Asian/Pacific Islander Income: 77% received <$1000/moEmployment: 63% employed‡Fin. aid: 55% received <$100 aid/mo‡Nationality: NC‡ | California State University—Sacramento (assumed) |

| Koller (52), thesis | Cross-sectional (random course selection) | College students, excluding those in study abroad experiences | 53 (11) | Sex: 72% femaleAge: 92% 18–22 yRace/ethnicity: 77% whiteIncome: 48% received <$10,000/yEmployment: 34% employed at least part-timeFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Bowling Green State University |

| Patton-López et al. (53), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (census) | College students | 354 (7) | Sex: 73% femaleAge: 72% 18–24 y Race/ethnicity: 8% LatinoIncome: 79% received <$15,000/yEmployment: 50% employedFin. aid: 76% received aidNationality: NR | Western Oregon University (assumed) |

| Davidson and Morrell (54), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Undergraduate students enrolled in a nutrition course, 18–24 y old | 211 (51) | Sex: 84% female Age: 18–24 y NRRace/ethnicity: 89% white‡Income: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: 67% received aid‡ Nationality: NR | University of New Hampshire |

| Fossman and King (38); Lindsley and King (23), report; conference abstract | Longitudinal (census) | College students living on a university campus | 65 (8) | Sex: 55% femaleAge: 21.6 ± 4.6 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 83% white‡Income: NC‡Employment: NR‡Fin. aid: NC‡Nationality: NC‡ | University of Alaska, Anchorage‡ |

| Maroto et al. (36); Maroto and Linck (21), peer-reviewed article; dissertation | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Community college students (urban and suburban) | 301 (62) | Sex: 55% femaleAge: 23 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 71% African AmericanIncome: 72% received ≤$750/moEmployment: NCFin. aid: NCNationality: NC | NR, 2 Maryland community colleges |

| Shelnutt (55), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (census) | Undergraduate and graduate students | 1891 (NR) | Sex: NRAge: NRRace/ethnicity: NRIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | University of Florida (assumed) |

| Silva et al. (56), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (random, stratified by classes) | Undergraduate and graduate students | 390 (2) | Sex: 60% femaleAge: 56% 18–22 yRace/ethnicity: 43% white, 26% Asian Income: NREmployment: 73% employed‡Fin. aid: 62% received aid‡Nationality: NR | University of Massachusetts—Boston |

| Bianco et al. (57), report | Cross-sectional (random) | College students | 707 (13) | Sex: NRAge: NRRace/ethnicity: 55% whiteIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | California State University, Chico |

| Bruening et al. (58), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Freshman college students | 209 (42) | Sex: 62% femaleAge: 18.8 ± 0.5 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 46% white, 27% HispanicIncome: NC‡Employment: 71% unemployed‡Fin. aid: 73% received Pell Grants Nationality: 6% international students‡ | Arizona State University (assumed) |

| Calvez et al. (59), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Undergraduate students | 205‡ (1‡) | Sex: 62% femaleAge: NR‡Race/ethnicity: NC‡Income: NC‡Employment: NC‡Fin. aid: NC‡Nationality: NC‡ | Texas A&M University |

| Dubick et al. (60), report | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Undergraduate students | 3765 (NC‡) | Sex: 57% femaleAge: 69% 18–21 yRace/ethnicity: 40% white, 19% Asian Income: 55% received ≤$49,999/yEmployment: NR‡Fin. aid: 43% Pell Grant eligibleNationality: 87% US citizen | 34 institutions; 8 community colleges and 26 4-y universities in 12 states |

| MacDonald (61), thesis | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Fulbright College of Arts/Sciences students living on a university campus | 467 (7) | Sex: 71% femaleAge: 23.2 ± 7.7 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 79% white Income: NC‡Employment: 58% employed at least part-timeFin. aid: NC‡Nationality: NC‡ | University of Arkansas |

| Maguire et al. (62), report | Cross-sectional (census) | Undergraduate and graduate students | 1554 (18‡) | Sex: 67% female‡Age: 24 ± 7 y‡ (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 61% white‡Income: NRFin. aid: NREmployment: NRNationality: NR | Humboldt State University |

| Mirabitur et al. (63), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (random) | Undergraduate, graduate, and non-degree-seeking students | 514 (7) | Sex: 53% female (weighted)Age: NR Race/ethnicity: 75% white (weighted)Income: NREmployment: NR Fin. aid: NRNationality: NR | University of Michigan (assumed) |

| Morris et al. (37); Morris (22), peer-reviewed article; thesis | Cross-sectional (census) | Undergraduate students | 1882 (4) | Sex: 67% femaleAge: NRRace/ethnicity: 77% whiteIncome: NREmployment: 64% employed at least part-timeFin. aid: 64% and 70% received aid that did or did not require repayment, respectivelyNationality: NR | Eastern Illinois, Northern Illinois, Southern Illinois, and Western Illinois Universities |

| Twill et al. (64), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (convenience) | College students | Nearly 150 (NC‡) | Sex: NC‡Age: NC‡Race/ethnicity: NC‡Income: NC‡Employment: NC‡Fin. aid: NC‡Nationality: NC‡ | Wright State University |

| Wood et al. (65), report | Cross-sectional (NR) | Community college students | 3647 (NR) | Sex: NRAge: NRRace/ethnicity: 31% white, 38% LatinoIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | California community colleges (n and names: NR) |

| Adamovic (66), thesis | Cross-sectional (convenience) | College students | 339 (1) | Sex: 77% femaleAge: NC‡Race/ethnicity: 55% whiteIncome: NC‡ Employment: 70% employed at least part-timeFin. aid: 56% and 44% received aid that did not and did require repayment, respectivelyNationality: NC‡ | University of Colorado—Boulder |

| Blagg et al. (19)—2-y students, report | Cross-sectional (stratified representative sample) | Households with student enrolled at undergraduate level | 3345 (76–88 month-over-month‡) | Sex: 54% female Age: 68% 18–25 y Race/ethnicity: 51% whiteIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | No specific universities under study |

| Blagg et al. (19)—4-y students, report | Cross-sectional (stratified representative sample) | Households with student enrolled at undergraduate level | 7035 (76–88 month-over-month‡) | Sex: 54% female Age: 77% 18–25 y Race/ethnicity: 61% white Income: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | No specific universities under study |

| Ellis et al. (67), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (convenience‡) | Undergraduate students | 344 (NC‡) | Sex: 87% femaleAge: 19 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 80% white‡Income: NC‡Employment: NC‡Fin. aid: NC‡Nationality: NC‡ | University of Alabama |

| Hillmer et al. (68), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (random course selection) | Undergraduate students | 197 (NR) | Sex: NRAge: NRRace/ethnicity: NRIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Southeast Missouri State University (assumed) |

| Holland et al. (69), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Undergraduate and graduate students | 629 (10‡) | Sex: 73% femaleAge: 21.2 ± 4.4 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: NRIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Winthrop University‡ |

| Kashuba (70), thesis | Cross-sectional (convenience) | College students | 1236 (≥7) | Sex: 73% femaleAge: NRRace/ethnicity: 70% whiteIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | University of Oregon |

| King (71), dissertation | Cross-sectional (census) | College students, excluding those in online-only program | 4188 (14) | Sex: 73% femaleAge: 84% 18–24 yRace/ethnicity: 79% whiteIncome: NREmployment: 62% employed at least part-timeFin. aid: 66% received aidNationality: 6% international students | Kent State University |

| Knol et al. (72), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (census) | College students ≥19 y old and living off-campus. Excluded if pregnant, ate at Greek fraternity/sorority houses, living with parents, married, or followed a restricted diet | 351 (∼3) | Sex: 72% femaleAge: 100% ≥19 y‡Race/ethnicity: 85% white Income: NR Employment: 47% employedFin. aid: 62% owed $0–999 in aidNationality: NC‡ | University of Alabama |

| Martinez (25); Martinez et al. (24; 39), report; conference abstract; peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (random) | Undergraduate and graduate students | 8705 (13) | Sex: 67% femaleAge: 23 ± 6 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 34% white, 31% Asian Income: NC‡Employment: NC‡Fin. aid: 65% received aidNationality: 9% international students | 10 University of California campuses |

| McArthur et al. (40); Danek (28), peer-reviewed article; thesis | Cross-sectional (random) | Nonfreshmen undergraduate and graduate students | 1093 (18) | Sex: 68% femaleAge: 21.7 ± 3.8 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 92% white Income: 77 received <$500/moEmployed: 63% employed at least part-time Financial aid: 64% received aidNationality: <1% international students | Appalachian State University‡ |

| Mercado (73), dissertation | Cross-sectional (census) | Community college students | 693 (3) | Sex: 70% femaleAge: 29.5 ± 11.1 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 29% white, 22% Hispanic Income: 55% received ≤$25,000/yEmployment: 61% employedFin. aid: 45% received aid Nationality: 14% non-US citizen or resident | Peralta Community College District (4 colleges) |

| Miles et al. (74), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (census) | Undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in the School of Social Work | 496 (55) | Sex: 86% femaleAge: 47% 25–34 yRace/ethnicity: 20% person of color; 12% HispanicIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Portland State University (assumed) |

| Poll et al. (75), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (NR) | NCAA Division 1 male college athletes | 93 (NR) | Sex: 100% maleAge: 19.7 ± 1.4 y (mean ± SD)Race: 48% white, 41% blackIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | University of Mississippi (assumed) |

| Wall-Bassett et al. (76), conference abstract | Cross-sectional (NR) | College students | 381 (94) | Sex: NRAge: NRRace/ethnicity: NRIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | Western Carolina University (assumed) |

| West (77), thesis | Cross-sectional (NR) | Latinx undergraduate students in an academic department with 97% Latinx enrollment | 50 (25) | Sex: 82% femaleAge: 18–27 y (range)Race/ethnicity: 100% LatinxIncome: NREmployment: 78% employedFin. aid: 50% received work-study Nationality: NR | University of California—Davis |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 1 (18); Goldrick-Rab et al. (32), peer-reviewed article; report | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Community college undergraduate students | 26,131 (4) | Sex: 72% femaleAge: 27.7 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 44% white, 24% Hispanic Income: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: NRNationality: NR | 73 community colleges in 24 states |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 2 (18); Goldrick-Rab et al. (29), peer-reviewed article; report | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Community college undergraduate students | 4185 (9) | Sex: 55% femaleAge: 29.8 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 55% whiteIncome: 44% received <$50,000/yEmployment: 62% employed in last weekFin. aid: 67% received aidNationality: 95% US citizen | 10 community colleges in 7 states |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 3 (18); Wisconsin HOPE Lab (34), peer-reviewed article; report | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Freshman and sophomore students. To be eligible, had an EFC ≤200% of the Pell Grant eligibility, had unmet financial need, and had an interest in a STEM field, would require remediation in math | 1007 (64) | Sex: 50% femaleAge: 19.4 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 79% whiteIncome: 43% earned <$50,000/yEmployment: NRFin. aid: 100% received aidNationality: NR | 10 public and private 2- and 4-y colleges in Wisconsin |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 4 (18); Broton et al. (26); Goldrick-Rab (27), peer-reviewed article; report; book | Cross-sectional, part of larger longitudinal study (stratified representative sample) | Undergraduate students who were Wisconsin residents, within 3 y of completing high school, qualified for a Pell Grant, and had unmet financial need of ≥$1 | 1442 (77) | Sex: 60% femaleAge: 18.4 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 71% whiteIncome: 88% received <$50,000/yEmployment: NR Fin. aid: 100% received aidNationality: NR | 42 public 2- and 4-y Wisconsin colleges and universities |

| Bruening et al. (78), peer-reviewed article | Longitudinal (convenience) | Freshman undergraduate students living in residence halls | 1138 (NR) | Sex: 65% femaleAge: NR Race/ethnicity: 51% whiteIncome: NREmployment: NRFin. aid: 33% received Pell GrantsNationality: NR | Arizona State University (assumed) |

| Crutchfield and Maguire (79), report | Cross-sectional (census) | College students | 24,324 (6) | Sex: 72% femaleAge: 23.6 y (mean)Race/ethnicity: 40% white, 23% AsianIncome: NR Employment: NCFin. aid: NCNationality: NC | 23 California State University campuses |

| Hagedorn and Olfert (41); Hagedorn et al. (33), peer-reviewed article; conference abstract | Cross-sectional (census of all courses) | Undergraduate and graduate students | 692 (2) | Sex: 71% femaleAge: 21.3 ± 4 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 87% whiteIncome: NR‡Employment: 54% employedFin. aid: 80% received aidNationality: 5% international students‡ | West Virginia University |

| McArthur et al. (80), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (random) | Freshmen undergraduate students | 456 (23) | Sex: 73% female Age: 18.5 ± 1.0 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 83% white Income: 97% received <$500/moEmployed: 21% employedFin. aid: 68% received aidNationality: NR‡ | Appalachian State University‡ |

| Payne-Sturges et al. (81), peer-reviewed article | Cross-sectional (convenience) | Undergraduate students | 237 (62) | Sex: 81% female Age: 20.7 ± 4.5 y (mean ± SD)Race/ethnicity: 49% white, 22% Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Income: 58% received ≥$70,000/yEmployment: 61% employedFin. aid: 64% received aidNationality: 20% born outside of the United States‡ | University of Maryland (assumed) |

| El Zein et al.‡ (42); El Zein et al. (31); Laitner et al. (30), article in preparation; conference abstract; conference abstract | Cross-sectional (convenience‡) | Freshmen undergraduate students, consuming <2 cups (472 mL) of fruits or <3 cups (708 mL) of vegetables daily, and meeting 1 of the following criteria: BMI ≥25 kg/m2, first-generation college student, parent that is overweight or obese, low-income background, or identify as a racial minority | 859 (NC‡) | Sex: 67% femaleAge: 62% 19 yRace/ethnicity: 62% white Income: NREmployment: 43% employed at least part-timeFin. aid: 40% received Pell GrantsNationality: NR | Auburn University, University of Florida, Syracuse University, University of Tennessee, University of Maine, South Dakota State University, West Virginia University, and Kansas State University |

1Sixty-six study citations are included from 62 independent records (i.e., publications) reporting on 51 distinct study samples. Study samples were identified by separating out records that included >1 study or sample as well as condensing multiple records reporting on the same study. ‡Information provided by authors. EFC, expected family contribution; Fin. aid, financial aid; NC, not collected; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association; NR, not reported; STEM, science, technology, engineering, and math.

FIGURE 2.

Bubble plot of each included study indicating publication year, food insecurity estimate, and survey used. The size of each bubble corresponds to the sample size of the study. “Other Surveys” includes modified FSSMs and novel questionnaires. For study samples with >1 affiliated publication, the year that the last publication was published is used. FSSM, Food Security Survey Module.

Most studies listed no or minimal eligibility criteria (i.e., enrolled students >18 y old) for study participation, with only 18 studies (35%) listing more restrictive criteria. Given the minimal eligibility criteria, it was common for studies to report including both graduate and undergraduate students (44%, n = 21). Although 1 study included only male collegiate athletes, it was more common for studies to include a higher proportion of female students, with a median of 70% among 43 studies. Studies commonly captured what would be considered the traditionally aged college student (18–24 y old), although studies varied in reporting the mean age or the percentage within this category. Among 21 studies reporting the mean age of their participants, the median across studies was 21.7 y old. Among the 14 studies reporting the percentage of students between 18 and 24 y old, the median across studies was 72%. Although the percentage of white students ranged from 0% to 92% among the n = 40 studies that reported race/ethnicity, the median was 55% white students. Few studies reported employment (n = 19) and financial aid (n = 17) characteristics, but among these studies a median of 61% of students were employed and 67% of students received financial aid (however, classifications of aid varied across studies). International student status was reported in 11 studies and the median was 9% international students.

Quality

Quality assessments of each study are presented in Table 3. The mean ± SD overall score for all studies was 6.4 ± 1.6, on a scale of 0–10. Studies ranged in quality ratings from 3 to 8. Most studies completely met the a priori hypothesis criteria, with only 1 study receiving a score of 1. The lowest mean ± SD criteria score, of 0.7 ± 0.4 across studies, was for sufficient sample reporting owing to a number of studies that did not report response rates (n = 11) and an absence of any nonresponse bias assessments. Response rates ranged from <1% to 99% with a median of 14% for the 38 studies that provided rates. Of the studies that reported their sampling strategy, convenience sampling (45%, n = 21) and census approaches (30%, n = 14) were the most common. Only 4 study samples used representative sampling strategies and 2 of these came from 1 report based on the Current Population Survey that measured FI at the household level. Quality assessments were not related to the literature type, with both gray and peer-reviewed literature scored moderately (mean: 6.2 and 6.5, respectively). Quality scores were higher for studies that included multiple institutions (mean: 6.9) than for those that were based out of 1 institution (mean: 6.2). Studies using one of the standard USDA Food Security Survey Modules (FSSMs) had greater quality scores (mean: 6.6) than studies using modified FSSMs or novel instruments (mean: 5.7).

TABLE 3.

Quality assessments of the studies examining US college student FI1

| Authors (Ref) | A priori aim/hypothesis | Study population clearly specified | Participant recruitment | Sample reporting | Reliable/valid FI surveys | Mean overall score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khachadourian (45) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Chaparro et al. (46) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Freudenburg et al. (47) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Magoc (48) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Gonzales (49) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Gaines et al. (20, 35) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Gorman (50) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Hanna (51) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Koller (52) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Patton-López et al. (53) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Fossman and King (38); Lindsley and King (23) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Maroto et al. (36); Maroto and Linck (21) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Silva et al. (56) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Bianco et al. (57) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Bruening et al. (58) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Calvez et al. (59) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Dubick et al. (60) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| MacDonald (61) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Maguire et al. (62) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Mirabitur et al. (63) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Morris et al. (37); Morris (22) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Twill et al. (64) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NR | 3 |

| Wood et al. (65) | 2 | 1 | NR | 0 | NR | 3 |

| Adamovic (66) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Blagg et al. (19)—both 2-y and 4-y samples | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kashuba (70) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| King (71) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Knol et al. (72) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Martinez (25); Martinez et al. (24, 39) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| McArthur et al. (40); Danek (28) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Mercado (73) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Miles et al. (74) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| West (77) | 2 | 2 | NR | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 1 (18); Goldrick-Rab et al. (32) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 2 (18); Goldrick-Rab et al. (29) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 3 (18); Wisconsin HOPE Lab (34) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 4 (18); Broton et al. (26); Goldrick-Rab (27) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Bruening et al. (78) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Crutchfield and Maguire (79) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Hagedorn and Olfert (41); Hagedorn et al. (33) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| McArthur et al. (80) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Payne-Sturges et al. (81) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| El Zein et al. (31, 42); Laitner et al. (30) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Criteria mean ± SD scores | 1.98 ± 0.15 | 1.53 ± 0.59 | 1.27 ± 0.98 | 0.74 ± 0.44 | 0.95 ± 0.31 | 6.37 ± 1.60 |

1Scoring criteria for each quality assessment component are reported in Table 1. Fifty-nine study citations are included from 56 independent records (i.e., publications) reporting on 43 distinct studies. These study samples were identified by separating out records that included >1 study, condensing multiple records reporting on the same study, and removing studies that were only published as an abstract. FI, food insecurity; NR, not reported.

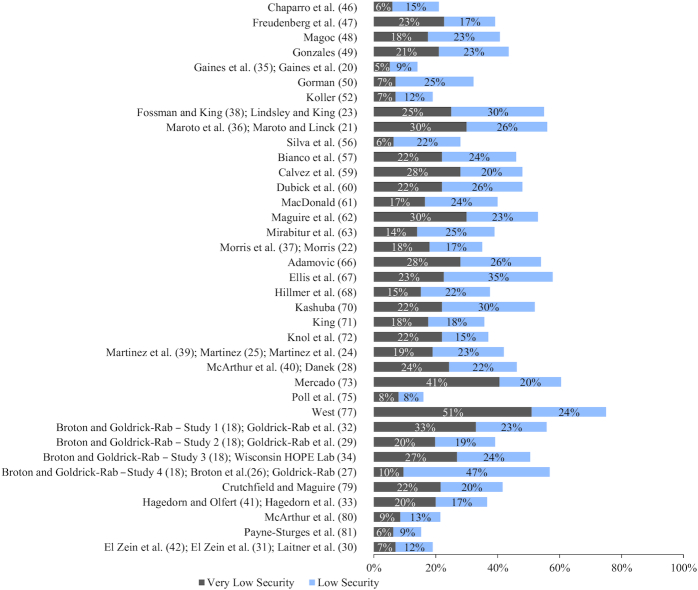

Estimates of FI

FI prevalence estimates ranged from 10% to 75% in all studies (see Table 4). The overall weighted estimate of FI across studies was 41%. Thirty-seven studies further classified these students with FI as having low or very low food security. Figure 3 presents these estimates, showing that it was common for very low security to be as prevalent as, or more prevalent than, low food security.

TABLE 4.

Assessment protocol characteristics of the studies examining US college student FI1

| Authors (Ref) | FI survey | FI reference period | FI survey method | FI prevalence, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khachadourian (45) | USDA Household FSSM, 18 items | 12 mo | In-person; mail | 43 |

| Chaparro et al. (46) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | In-class | 21 |

| Freudenberg et al. (47) | Modified USDA FSSM, 4 items | 12 mo | Online; phone | 39 |

| Magoc (48) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 3 mo | Online | 41 |

| Gonzales (49) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | Online | 44‡ |

| Gaines et al. (20, 35) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | In-class | 14 |

| Gorman (50) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | Online | 32 |

| Hanna (51) | Modified USDA FSSM with 1-item screener‡ | 12 mo | Online | 19 |

| Koller (52) | Gave FI definitions and asked students to select | None | Online | 19 |

| Patton-López et al. (53) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online | 59 |

| Davidson and Morrell (54) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online | 12‡ |

| Fossman and King (38); Lindsley and King (23) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items‡ | 4 mo‡ | Online‡ | 55 in summer; 78 in fall |

| Maroto et al. (36); Maroto and Linck (21) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | In-person | 56 |

| Shelnutt (55) | USDA FSSM, items NR | NR | Online | 10 |

| Silva et al. (56) | Modified USDA FSSM, 4 items | 12 mo | In-person | 28‡ |

| Bianco et al. (57) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online | 46 |

| Bruening et al. (58) | Adapted screener, 2 items | 1 mo; 3 mo | Online | 32 in 1 mo; 37 in 3 mo |

| Calvez et al. (59) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | “During the semester at TAMU” | Online | 48 |

| Dubick et al. (60) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 30 d | Online | 48 |

| MacDonald (61) | Modified USDA FSSM, 8 items | 12 mo | Online | 40 |

| Maguire et al. (62) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d | Online | 53 |

| Mirabitur et al. (63) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online | 41 (weighted) |

| Morris et al. (37); Morris (22) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 9 mo | Online | 35 |

| Twill et al. (64) | Gave FI definitions and asked students to select‡ | 12 mo‡ | Online | 48 |

| Wood et al. (65) | Stressful life events scale | NR | NR | 12 |

| Adamovic (66) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online | 54 |

| Blagg et al. (19)—2-y students | USDA Household FSSM, 18 items | 12 mo | Phone | 17 |

| Blagg et al. (19)—4-y students | USDA Household FSSM, 18 items | 12 mo | Phone | 11 |

| Ellis et al. (67) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d‡ | Online‡ | 58‡ |

| Hillmer et al. (68) | USDA FSSM, items NR | NR | NR | 38 |

| Holland et al. (69) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items‡ | 12 mo | Online; in-person | 48 |

| Kashuba (70) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d | Online | 52 |

| King (71) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 3 mo | Online | 36 |

| Knol et al. (72) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | Online | 37 |

| Martinez et al. (24, 39); Martinez (25) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online | 42 (weighted) |

| McArthur et al. (40); Danek (28) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | Online | 46 |

| Mercado (73) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d | Online | 61 |

| Miles et al. (74) | Modified USDA Household FSSM, 15 items | 12 mo | Online | 43 |

| Poll et al. (75) | USDA FSSM, items NR | Related to high school | NR | 16 |

| Wall-Bassett et al. (76) | USDA FSSM, items NR | NR | Online | 38 |

| West (77) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | Online | 75 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 1 (18); Goldrick-Rab et al. (32) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d | Online | 56 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 2 (18); Goldrick-Rab et al. (29) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d | Online | 39 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 3 (18); Wisconsin HOPE Lab (34) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 12 mo | Online; NR‡ | 51 |

| Broton and Goldrick-Rab—Study 4 (18); Broton et al. (26); Goldrick-Rab (27) | Adapted screener, 1 item | 30 d | Online; mail | 57 |

| Bruening et al. (78) | USDA Short Form FSSM, 6 items | 30 d | Online | 28 |

| Crutchfield and Maguire (79) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 30 d | Online | 42 |

| Hagedorn and Olfert (41); Hagedorn et al. (33) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | Online | 37 |

| McArthur et al. (80) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | Previous academic year at school | Online | 22 |

| Payne-Sturges et al. (81) | USDA Household FSSM, 18 items | 12 mo | Online | 15 |

| El Zein et al.‡ (42); El Zein et al. (31); Laitner et al. (30) | USDA Adult FSSM, 10 items | 12 mo | In-person | 19 |

1Sixty-six study citations are included from 62 independent records (i.e., publications) reporting on 51 distinct study samples. These study samples were identified by separating out records that included >1 study or sample as well as condensing multiple records reporting on the same study. ‡Information provided by authors. FI, food insecurity; FSSM, Food Security Survey Module; NR, not reported.

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of low and very low food security in review of studies of college students. Studies that did not report low and very low food security rates are not shown.

Estimates of FI by surveying protocols

Table 4 details the FI assessment protocols of the included studies. Most studies (80%, n = 41) reported the use of USDA FSSMs to assess FI. The 6-item Short FSSM and the 10-item Adult FSSM together accounted for 65% of protocols. However, there was a subset of 4 studies (8%) which reported use of USDA FSSMs without specifying the survey form used. Although the minority, another 10 studies used novel FI assessment protocols without standard security categorizations to compare with prior FI research. Figure 2 provides a visual comparison of the FI estimates produced by these varying questionnaires. The weighted FI estimate produced in the studies based on a household measure using the 18-item FSSM was 13%. In contrast, FI estimates from studies using shorter FSSMs were larger, with 50% from the 6-item Abbreviated FSSM and 40% from the 10-item Adult FSSM. The studies using a variety of novel surveys produced a FI estimate of 31% but ranged from 12% to 48%. Among the 44 studies that reported the FI reference period, the majority (64%) asked students to refer to the last 12 mo. Another 5 studies used novel reference periods of 3, 4, and 9 mo. FI estimates produced from studies using reference periods <12 mo were larger (47%) than those using a 12-mo reference (31%).

FI estimates by institutional setting

The weighted estimate from the studies that included only community college students indicated 47% FI. Studies that included solely 4-y university students produced a weighted estimate of 36% FI. Samples that included students from both institution types produced an estimate of 41% FI. Other institutional setting characteristics, such as cost of attendance, may be related to FI estimates, but these were not consistently reported in the included records.

Discussion

The aims of this scoping review were to develop a weighted estimate of FI among US college students, to evaluate the quality of the literature, and to describe study characteristics that were related to prevalence estimates. An estimated 41% of US college students reported experiences of FI. However, this prevalence was dramatically different with varying assessment protocols, including the survey form and reference period. To the authors’ knowledge, the current review serves as the most comprehensive review of the literature. This approach has revealed several insights from the literature: 1) the body of work is distinct from the general FI literature; 2) psychometric testing of the USDA FSSMs is warranted; 3) reference periods used in FI surveys are important; 4) the impact of the institution needs further investigation; and 5) measurement accuracy is essential to understanding predictors and consequences among students experiencing FI.

The composition and quality of the literature studying FI among college students are distinct from the general FI literature. First, there is a large proportion of gray literature (i.e., online reports and academic theses) and conference abstracts. These variations in publication channels may explain the variation in the number of studies included in prior reviews (13, 14). The quantity and rigor of peer reviews are also variable in gray publications. The area of college FI research is rapidly growing in size. The first record in this review was published in 1999, but it was the only college FI research for almost 10 y until 2009. Since then, work in this area has grown at an exponential pace resulting in >30 records published in 2016 or later. Studies were commonly cross-sectional, limited to students from a single institution, recruited a convenience sample, used minimal eligibility criteria, and frequently focused on the 18- to 24-y-old student population.

The quality of studies was moderate, with a mean rating of 6.4 on a scale of 0–10. Response rates were a common issue in the literature. Twenty-five percent of the study samples did not report a response rate. Among the studies that reported response rates, 53% of the rates were <15%. It should also be noted that no studies examined potential nonresponse biases, which is concerning given the observed response rates. Four study samples were recruited using representative sampling techniques (18, 19, 26, 27, 47); these studies were ranked among those with the highest quality and had response rates >15%. The FI prevalence estimates from these 4 samples differed from 11% to 57% (18, 19, 26, 27, 47), but this may be due to the unique sample characteristics or surveying methods used. The characteristics of the majority of studies allow for this review to capture a broad characterization of FI prevalence among traditional university students, but the ability to talk about specific subpopulations is hindered. Further, there are concerns about interpreting the overall estimate of FI prevalence produced from this review and generalizing this as the population prevalence, given the heterogeneity across studies.

The various surveying protocols in the literature produced a range of prevalence estimates. Unlike what was expected and suggested by the findings in Nazmi et al. (14), the novel surveys with untested methods did not seem to systematically under- or over-estimate FI when compared with the USDA FSSMs. This may be due to the variety of surveys captured in the other/novel category. To clearly test the FI measurement variation of individual novel surveys additional psychometric testing would be needed. Surprisingly, the greatest variability between FI estimates was produced when comparing USDA FSSMs of different lengths. This is concerning because there is a legacy of strong psychometric evaluation conducted on these surveys that supports their use (82–87) and they have been broadly adopted for various settings across the United States and internationally. However, the surveys have limited formal psychometric evaluation among college students. One gray report refers to instrument testing (79), but given the aim of the report to broadly highlight the issues among college students, specific results of these psychometric evaluations were not described. A recent study from Nikolaus et al. (88) described the psychometric evaluation of the USDA FSSMs among college students and findings were consistent with this review in that the 6-item USDA FSSM produced the most liberal prevalence estimates. However, the 18-item USDA FSSM, which produced the lowest FI estimate in the current review, was not tested in this recent psychometric study (88). The limited use and testing of the 18-item Household FSSM are likely due to its incorporation of 8 items specifically querying about children in the household and the low proportion of college students with children. Finally, the current review demonstrates that very low food security was commonly as prevalent as low food security among college students, which diverges from the expected pattern of lower rates of very low food security than of low food security in the general US population (1).

Prevalence estimates were not only related to the survey form used, but also varied by the reference period used in the survey. The present review found that a lower FI prevalence resulted from surveys using a 12-mo reference period. This may be a result of recall bias (i.e., it is harder to remember a year's worth of experiences), but it could also be due to lower rates of FI experiences among students when not enrolled in school. McArthur et al. (80) evaluated FI among freshmen both before and during their enrollment and found higher FI rates after enrollment than before enrollment. The inclusion of months where the student is not enrolled, and possibly living with family may, in part, explain the lower rates produced when using a 12-mo reference period. It is possible that the variation in FI prevalence across surveying protocols (both survey form and reference period) can be a result of study characteristics, such as institution type. However, the distribution of surveying methods was fairly mixed across institution type and other study characteristics of interest in the current review. Therefore, psychometric evaluations of these protocols are warranted to ensure that FI prevalence estimates are accurate and policy efforts can be assessed with fidelity.

There is high heterogeneity in sample characteristics across the included studies. This high heterogeneity across studies may, in part, be explained by the inherent heterogeneity of education institutions. The variation in FI estimates produced from studies with community college students when compared with 4-y university students may be related to the unique characteristics of these student populations (89, 90). However, it was not common for estimates of FI to be separately reported for community college and university students. This practice limits the ability to understand how these student populations uniquely experience FI. In the future, separating estimates of FI for community college and university students is supported. In addition, beyond this dichotomy there are other institution characteristics that may be related to student FI. Enrollment cost, institution selectivity, student body size, proportion of first-generation students, and academic preparedness may be related to student FI experiences and this requires further investigation. In this review, other sample characteristics were not compared with FI estimates but this is because of the low number of reports that included demographic variables of interest.

Improvements in FI measurement accuracy among students will be essential to advance the field. Individual-level predictors and consequences of FI among US college students was initially a tertiary research question in the present review, because this is essential information in leveraging resources to best serve students. However, the results indicating variability in FI estimates produced by the different FSSMs elicited concerns about the validity and reliability of these methods for this population. These results, coupled with the recent study indicating student responses had poor fit to the FSSM Rasch model (88), suggest that current surveying methods are potentially misclassifying a proportion of students as food secure or insecure. FI experiences among students may not be best captured with our current methods. If individual-level correlates of FI are assessed with inaccurate methodology, relations will be imprecise, leading to under- or over-estimation of effects. Results of observational work are often used to inform policies and alleviation efforts. If these interventions are based on surveys with misclassification biases, not only do they run the risk of not reaching their target population but their long-term evaluations of efficacy may be weakened. Given this, it is imperative to develop new FI surveys or test existing instruments to ensure that experiences among students are optimally captured. Future research should include cognitive interviews and quantitative validity studies. Looking forward, once the FI surveying evaluations have been made, research evaluating FI risk factors and effects of policies on FI will be essential. One particularly valuable question is the relation of student income and FI. Many of the included studies attempted to measure student income or financial resources, but methods were inconsistent and it is difficult to ascertain the financial situation of students. This is due to the spectrum of financial independence that is seen in student populations, where familial support may be present, but the amount and frequency of support are often difficult to quantify (88).

There are limitations that should be accounted for when interpreting this review. It is possible that some studies evaluating FI among college students may have been missed. The systematic nature of the review supplemented with personal contact between researchers in the field have strengthened the comprehensiveness for inclusion of as many studies published before June 2018 as possible. However, this area of research is rapidly growing, as evidenced by the rate of publications in the last 3 y. It is possible that eligible studies have been published since the synthesis and analysis began in 2018.

This review estimates that 41% of US college students experience FI; this estimate should be interpreted and used with caution. There is wide heterogeneity among studies and it is worth considering the differences in student populations at various institutions. Further, the potential influence of surveying methods on the resulting FI estimates in the included studies necessitates future in-depth investigations focused on understanding the manifestation, progression, and presentation of FI among students. FI is clearly an issue in this population and could have a detrimental impact on students’ diet and academic success. Once surveying methods have been improved, testing policies and initiatives to alleviate FI, including those already undertaken as well as future developments (12), will be invaluable. Addressing FI among college students is imperative to ensure health, wellbeing, and professional success in the next generation.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CJN, BE, and SMN-R: conceived the study, designed the study, and conducted the data extractions/quality assessments; CJN: led the literature search, contacted study authors for supplemental information, and drafted the manuscript; CJN and RA: analyzed the data; and all authors: contributed to revising the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by National Institute of Food and Agriculture, USDA, award ILLU-470-334 (to BE). CJN received support from the Seymour Sudman Dissertation Award from the Survey Research Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

References

- 1. Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2017. [Internet] Washington (DC): USDA Economic Research Service; 2018; [cited 11 July, 2019]. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=90022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food-insufficient and food-sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirkpatrick SI, Tarasuk V. Food insecurity is associated with nutrient inadequacies among Canadian adults and adolescents. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):604–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park CY, Eicher-Miller HA. Iron deficiency is associated with food insecurity in pregnant females in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(12):1967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jones AD. Food insecurity and mental health status: a global analysis of 149 countries. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):264–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heflin CM, Ziliak JP. Food insufficiency, food stamp participation, and mental health. Soc Sci Q. 2008;89(3):706–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto KL, Gossett JM, Robbins JM, Simpson PM, Connell C, Bogle ML. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. J Nutr. 2004;134(9):2330–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr. 2003;133(1):120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seligman HK, Bindman AB, Vittinghoff E, Kanaya AM, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1018–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andrews M. For many college students, hunger ‘makes it hard to focus’. [Internet] Washington (DC): NPR; 2018; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/07/31/634052183/for-many-college-students-hunger-makes-it-hard-to-focus. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Government Accountability Office (GAO) Food insecurity: better information could help eligible college students access federal food assistance benefits. [Internet] Washington (DC): US GAO; 2018; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-19-95. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bruening M, Argo K, Payne-Sturges D, Laska MN. The struggle is real: a systematic review of food insecurity on postsecondary education campuses. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(11):1767–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nazmi A, Martinez S, Byrd A, Robinson D, Bianco S, Maguire J, Crutchfield RM, Condron K, Ritchie L. A systematic review of food insecurity among US students in higher education. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2019;14(5):725–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.0. [Internet] Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nikolaus CJ, Nickols-Richardson SM, Ellison B. Food insecurity among college students in the U.S.: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [Internet]. PROSPERO:CRD42017069902 York, UK: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2017. Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42017069902. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Broton KM, Goldrick-Rab S. Going without: an exploration of food and housing insecurity among undergraduates. Educ Res. 2018;47(2):121–33. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blagg K, Gundersen C, Schanzenbach DW, Ziliak JP. Assessing food insecurity on campus: a national look at food insecurity among America's college students. [Internet] Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2017; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/assessing-food-insecurity-campus. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaines A, Knol LL, Robb CA, Sickler SM. Food insecurity is related to cooking self-efficacy and perceived food preparation resources among college students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(9):A11. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maroto ME, Linck H. Food insecurity among community college students: prevalence and relationship to GPA, energy, and concentration [dissertation]. Baltimore, MD: Morgan State University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris LM. The presence of high, marginal, low and very low food security among Illinois university students [thesis]. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindsley K, King C. Food insecurity of campus-residing Alaskan college students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(9S):A94. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martinez S, Brown E, Ritchie L. What factors increase risk for food insecurity among college students?. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(7):S4. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martinez SM. Student food access and security study. [Internet] Oakland, CA: Nutrition Policy Institute; 2016; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://www.regents.universityofcalifornia.edu/regmeet/july16/e1attach.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Broton K, Frank V, Goldrick-Rab S. Proceedings from Association of Public Policy and Management: Safety, Security, and College Attainment: An investigation of undergraduates’ basic needs and institutional responses. [Internet] Albuquerque, NM; November 6-8, 2014; [cited 14 October, 2019]. Available from: http://rootcausecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Safety-Security-and-College-Attainment-An-Investigation-of-Undergraduates-Basic-Needs-and-Institutional-Response.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goldrick-Rab S. Paying the price: college costs, financial aid, and the betrayal of the American dream. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Danek A. Food insecurity and related correlates among students attending Appalachian State University [thesis]. Boone, NC: Appalachian State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goldrick-Rab S, Broton K, Eisenberg D. Hungry to learn: addressing food and housing insecurity among undergraduates. [Internet] Madison, WI: Wisconsin HOPE Lab; 2015; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://acct.org/product/hungry-learn-addressing-food-and-housing-insecurity-among-undergraduates-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Laitner M, Mathews A, Colby S, Olfert M, Leischner K, Brown O, Greene G. Prevalence of food insecurity and associated health behaviors among college freshmen. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):A30. [Google Scholar]

- 31. El Zein A, Shelnutt K, Colby S, Olfert M, Kattelmann K, Brown O, Vilaro M. Socio-demographic correlates and predictors of food insecurity among first year college students. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):A146. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goldrick-Rab S, Richardson J, Hernandez A. Hungry and homeless in college: results from a national study of basic needs insecurity in higher education. [Internet] Madison, WI: Wisconsin HOPE Lab; 2017; [cited 14 October, 2019]. Available from: http://www.hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Hungry-and-Homeless-in-College-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hagedorn RL, Barr ML, Famodu OA, Morris AM, Clark RL, Olfert MD. Food insecurity among college students at West Virginia University and self-reported health status. FASEB J. 2017;31(1_Supplement):791.32. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wisconsin HOPE Lab What we're learning: food and housing insecurity among college students: a data update from the Wisconsin HOPE Lab. [Internet] Madison, WI: Wisconsin HOPE Lab; 2016; [cited 14 October, 2019]. Available from: http://www.theotx.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Wisconsin_HOPE_Lab_data-Brief-16-01_Undergraduate_housing-and_Food_Insecurity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gaines A, Robb CA, Knol LL, Sickler S. Examining the role of financial factors, resources and skills in predicting food security status among college students. Int J Consum Stud. 2014;38(4):374–84. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maroto ME, Snelling A, Linck H. Food insecurity among community college students: prevalence and association with grade point average. Community Coll J Res Pract. 2015;39(6):515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morris LM, Smith S, Davis J, Null DB. The prevalence of food security and insecurity among Illinois university students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(6):376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fossman K, King C. Food insecurity in college students: a call to action in higher education. . NDEP-Line [Internet] 2015; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: http://www.ndepnet.org/member/newsletterarchive/ [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martinez SM, Webb K, Frongillo EA, Ritchie LD. Food insecurity in California's public university system: what are the risk factors?. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;13(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 40. McArthur LH, Ball L, Danek AC, Holbert D. A high prevalence of food insecurity among university students in Appalachia reflects a need for educational interventions and policy advocacy. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;50(6):564–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hagedorn RL, Olfert MD. Food insecurity and behavioral characteristics for academic success in young adults attending an Appalachian university. Nutrients. 2018;10(3):361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. El Zein A, Shelnutt KP, Colby S, Vilaro MJ, Zhou W, Greene G, Olfert MD, Riggsbee K, Morrell JS, Mathews AE. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among U.S. college students: a multi-institutional study. BMC Pub Health. 2019;19:660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cole NC, An R, Lee SY, Donovan SM. Correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2017;75(7):516–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Methods guide for effectiveness and comparative effectiveness reviews. [Internet] Rockville, MD: AHRQ; 2015; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/cer-methods-guide/overview/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Khachadourian I. The prevalence of food insecurity among reentry woman students and their children at California State University, Fresno [dissertation]. Fresno, CA: California State University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chaparro MP, Zaghloul SS, Holck P, Dobbs J. Food insecurity prevalence among college students at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(11):2097–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Freudenberg N, Manzo L, Jones H, Kwan A, Tsui E, Gagnon M. Food insecurity at CUNY: results from a survey of CUNY undergraduate students. [Internet] New York: City University of New York; 2011; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://www.gc.cuny.edu/CUNY_GC/media/CUNY-Graduate-Center/PDF/Centers/Center%20for%20Human%20Environments/cunyfoodinsecurity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Magoc T. Physical activity and household food insecurity as important predictors of health status in EIU students [thesis]. Charleston, IL: Eastern Illinois University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gonzales K. The impact of residence on dietary intake, food insecurity, and eating behavior among university undergraduate students. Ursidae. 2013;3(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gorman A. Food insecurity prevalence among college students at Kent State University [thesis]. Kent, OH: Kent State University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hanna L. Evaluation of food insecurity among college students. Am Int J Contemp Res. 2014;4(4):46–9. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Koller K. Extent of BGSU student food insecurity and community resource use. [Internet]. Honors Projects, Paper 144 Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University; 2014; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/144/ [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patton-López MM, López-Cevallos DF, Cancel-Tirado DI, Vazquez L. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among students attending a midsize rural university in Oregon. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3):209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Davidson A, Morrell J. Food insecurity among undergraduate students. FASEB J. 2015;29(1_Supplement):LB404. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shelnutt K. Determining the need for a food pantry on a university campus. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(4S):S55. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Silva MR, Kleinert WL, Sheppard AV, Cantrell KA, Freeman-Coppadge DJ, Tsoy E, Roberts T, Pearrow M. The relationship between food security, housing stability, and school performance among college students in an urban university. J Coll Stud Ret. 2017;19(3):284–99. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bianco S, Bedore A, Jiang M, Stamper N, Breed J, Paiva M, Abbiati L. Identifying food insecure students and constraints for SNAP/CalFresh participation at California State University, Chico. [Internet] Chico, CA: California State University, Chico; 2016; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: http://www.csuchico.edu/chc/_assets/documents/chico-food-insecurity-report-2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bruening M, Brennhofer S, Van WI, Todd M, Laska M. Factors related to the high rates of food insecurity among diverse, urban college freshmen. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):1450–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Calvez K, Miller C, Thomas L, Vazquez D, Walenta J. The university as a site of food insecurity: evaluating the foodscape of Texas A&M University's main campus. Southwestern Geographer. 2016;19:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Dubick J, Mathews B, Cady C. Hunger on campus: the challenge of food insecurity for college students. [Internet] Boston, MA: Students Against Hunger; 2016; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: http://studentsagainsthunger.orghttps://studentsagainsthunger.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Hunger_On_Campus.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 61. MacDonald A. Food insecurity and educational attainment at the University of Arkansas [thesis]. [Internet] Fayetteville: University of Arkansas; 2016; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/scwkuht. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Maguire J, O'Neill M, Aberson C. California State University food and housing security survey: emerging patterns from the Humboldt State University data. [Internet] Arcata, CA: Humboldt State University; 2016; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: http://hsuohsnap.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ExecutiveSummary.docx1-14-16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mirabitur E, Peterson KE, Rathz C, Matlen S, Kasper N. Predictors of college-student food security and fruit and vegetable intake differ by housing type. J Am Coll Health. 2016;64(7):555–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Twill SE, Bergdahl J, Fensler R. Partnering to build a pantry: a university campus responds to student food insecurity. J Poverty. 2016;20(3):340–58. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wood JL, Harris F III, Delgado NR. Struggling to survive – striving to succeed: food and housing insecurities in the community college. San Diego, CA: Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Adamovic E. Food insecurity among college students: an assessment of prevalence and solutions [thesis]. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Boulder; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ellis A, Burns T, Buzzard J, Dolan L, Register S, Crowe-White K. Food insecurity among college students does not differ by affiliation in Greek life. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):A145. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hillmer A, Timlin MT, Tayie FA, Faber A. Prevalence of food insecurity among college students at a small Midwestern university. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(9):A92. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Holland R, Barbera A, Sadek A, Koszewski W, Brooks G. Prevalence of food insecurity among college students at a Southeastern university. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(9):A93. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kashuba KE. The prevalence, correlates, and academic consequences of food insecurity among University of Oregon students [dissertation]. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 71. King J. Food insecurity among college students – exploring the predictors of food assistance resource use [thesis]. Kent, OH: Kent State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Knol LL, Robb CA, McKinley EM, Wood M. Food insecurity, self-rated health, and obesity among college students. Am J Health Educ. 2017;48(4):248–55. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mercado V. Food and housing insecurity among students at a community college district [dissertation]. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Miles R, McBeath B, Brockett S, Sorenson P. Prevalence and predictors of social work student food insecurity. J Soc Work Educ. 2017;53(4):651–63. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Poll K, Valliant M, Joung H-WD, Holben DH. Food insecurity and food behaviors of male collegiate athletes. FASEB J. 2017;31(1_supplement):791.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wall-Bassett E, Li Y, Matthews F. The association of food insecurity and stress among college students in rural North Carolina. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49(7):S75. [Google Scholar]

- 77. West AN. The struggle is real: an exploration of the prevalence and experiences of low-income Latinx undergraduate students navigating food and housing insecurity at a four-year research university [dissertation]. Sacramento, CA: California State University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bruening M, van Woerden I, Todd M, Laska MN. Hungry to learn: the prevalence and effects of food insecurity on health behaviors and outcomes over time among a diverse sample of university freshmen. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Crutchfield R, Maguire J. California State University Office of the Chancellor study of student basic needs. [Internet] Long Beach, CA: California State University Office of the Chancellor; 2018; [cited 7 February, 2019]. Available from: http://www.calstate.edu/basicneeds. [Google Scholar]

- 80. McArthur LH, Fasczewski KS, Wartinger E, Miller J. Freshmen at a university in Appalachia experience a higher rate of campus than family food insecurity. J Community Health. 2018;43(8):969–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Payne-Sturges DC, Tjaden A, Caldeira KM, Vincent KB, Arria AM. Student hunger on campus: food insecurity among college students and implications for academic institutions. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(2):349–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Frongillo EA., Jr Validation of measures of food insecurity and hunger. J Nutr. 1999;129(2):506S–9S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Campbell CC. Food insecurity: a nutritional outcome or a predictor variable?. J Nutr. 1991;121(3):408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Carlson SJ, Andrews MS, Bickel GW. Measuring food insecurity and hunger in the United States: development of a national benchmark measure and prevalence estimates. J Nutr. 1999;129(2):510S–16S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]