ABSTRACT

Observational studies provide strong evidence for the health benefits of dietary fiber (DF) intake; however, human intervention studies that supplement isolated and synthetic DFs have shown inconsistent results. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to summarize the effects of DF supplementation on immunometabolic disease markers in intervention studies in healthy adults, and considered the role of DF dose, DF physicochemical properties, intervention duration, and the placebo used. Five databases were searched for studies published from 1990 to 2018 that assessed the effect of DF on immunometabolic markers. Eligible studies were those that supplemented isolated or synthetic DFs for ≥2 wk and reported baseline data to assess the effect of the placebo. In total, 77 publications were included. DF supplementation reduced total cholesterol (TC), LDL cholesterol, HOMA-IR, and insulin AUC in 36–49% of interventions. In contrast, <20% of the interventions reduced C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, glucose, glucose AUC, insulin, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. A higher proportion of interventions showed an effect if they used higher DF doses for CRP, TC, and LDL cholesterol (40–63%), viscous and mixed plant cell wall DFs for TC and LDL cholesterol (>50%), and longer intervention durations for CRP and glucose (50%). Half of the placebo-controlled studies used digestible carbohydrates as the placebo, which confounded findings for IL-6, glucose AUC, and insulin AUC. In conclusion, interventions with isolated and synthetic DFs resulted mainly in improved cholesterol concentrations and an attenuation of insulin resistance, whereas markers of dysglycemia and inflammation were largely unaffected. Although more research is needed to make reliable recommendations, a more targeted supplementation of DF with specific physicochemical properties at higher doses and for longer durations shows promise in enhancing several of its health effects.

Keywords: dietary fiber, dysglycemia, insulin resistance, systemic inflammation, dyslipidemia, adults

Introduction

Obesity and its associated comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), have reached epidemic proportions in countries that have adopted a Western diet (1). This diet is typically low in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, all of which are the only food sources of dietary fiber (DF) (2). DF is defined as nondigestible carbohydrate polymers that either occur naturally in food (intrinsic and intact DFs), are isolated from food (by physical, enzymatic, or chemical means) or are chemically synthesized, the latter 2 requiring evidence to support their physiological benefit to health (2). DF is considered by most health professionals and regulatory agencies to be an integral component of a healthy diet, being implicated in the reduction of chronic diseases (3, 4). Observational studies support the health benefits of high DF intake (5), such as a reduction in low-grade systemic inflammation (6), obesity (7), metabolic syndrome (8, 9), type 2 diabetes (10, 11), and CVD (12, 13), as well as all-cause mortality (14). In addition, a substantial body of research in animal disease models has demonstrated health-promoting effects of isolated and synthetic DFs and established mechanisms by which pathologies are prevented (15, 16). DF sequesters bile acids and cholesterol in the small intestine and promotes their excretion (17), whereas viscous DFs impede the absorption of glucose and lipids (18). Further, fermentation of DF by the gut microbiota leads to the production of SCFAs, which have a wide variety of immunological, metabolic, and hormonal effects, such as promoting satiety, reducing inflammation, and improving glucose and lipid metabolism (19, 20).

The average intake of DF remains decidedly inadequate in affluent societies despite considerable efforts from policymakers and health professionals to increase consumption of whole foods (21). A more promising strategy to enhance DF consumption, and thereby overall health, could potentially be achieved by enriching the food supply with isolated or synthetic DFs (22, 23). However, despite the convincing effects of DF found in observational (5, 13) and animal studies (15, 16), results of human intervention trials with isolated and synthetic DFs are inconsistent (24). Buyken and colleagues systematically reviewed observational studies that assessed the relation between DF intake and systemic inflammation, and compared these findings to results of intervention studies that provided DF supplements (6). Only a single intervention study out of 11 reported a significant reduction in C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations, whereas 13 out of 16 observational studies reported a significant inverse association between systemic inflammation and DF intake. Further, Thompson et al. reported improvements in body weight and glycemia from isolated soluble DF in overweight and obese populations in a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies, but the authors recommended caution in the interpretation of these findings due to significant between-study heterogeneity (23). These findings raise important questions: why do observational studies more consistently show beneficial effects of increased DF intake compared with intervention trials, and are isolated and synthetic DFs a viable alternative to whole foods rich in intrinsic and intact DFs?

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the effect of isolated and synthetic DF supplementation on well-established risk markers of metabolic disease related to glycemia, systemic inflammation, and lipidemia in intervention studies in healthy and/or at-risk adults. We further determined whether reported effects differed based on DF dose, DF physicochemical properties, intervention duration, and the placebo used. Given the extensive heterogeneity in the study designs used in the included publications (e.g., single-arm and multi-arm interventions), a meta-analysis was not conducted. Instead, we summarized the results to provide recommendations for the design of future interventions aimed at elucidating the role of DF supplementation in the prevention of chronic disease.

Methods

In order to achieve a comprehensive overview of the available literature on isolated and synthetic DF, we included randomized placebo-controlled trials, as well as pilot studies and single-arm interventions trials that assessed a wide range of immunometabolic markers. This resulted in extensive heterogeneity in the designs of the studies found and, consequently, a meta-analysis was not completed. This systematic review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (25), as well as the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and Interventions guidelines (26). Although the study was not registered with PROSPERO, no deviations from the original protocol were made.

Study selection criteria

Since the objective of this review was to assess the ability of DF supplementation to reduce disease risk in both healthy adults and those at risk of metabolic diseases (e.g., hypercholesterolemia, prediabetes), we focused on well-established markers of pathophysiologies of obesity and its comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes and CVD. These immunometabolic markers were grouped under the following themes: 1) dysglycemia and insulin resistance (fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, and postprandial glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose tolerance test, described as glucose AUC and insulin AUC), 2) systemic inflammation (fasting CRP and IL-6), and 3) dyslipidemia [fasting total cholesterol (TC), LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (TG)]. Human intervention studies with a range of experimental designs (e.g., randomized placebo-controlled studies, single-arm studies, and pilot studies) published in English that assessed the effect of DF supplements with ≥50% DF content per gram dry weight on the markers of interest were included.

The gold standard for investigating the effectiveness of an intervention is a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. The placebo should be as similar as possible to the treatment in appearance but physiologically and functionally inert; therefore, having no effect on the primary outcomes (27). This is often difficult to achieve in nutrition research (28), as the placebo may adversely affect the assessed outcomes, which is the case for placebos composed of digestible carbohydrates since these have been shown to negatively affect immunometabolic markers (29, 30). We, therefore, excluded studies that did not report baseline data for each intervention arm, or if such data could not be obtained from the authors upon request, as these studies did not allow us to quantify the effect of the placebo.

The selection criteria are summarized in Table 1. Studies with multiple treatment arms were included if ≥1 arm met inclusion criteria. Intervention arms that tested DF together with calorie restriction protocols, medications, probiotics, or in the context of whole-food treatments were excluded, as these interventions may have had DF-independent effects on the immunometabolic markers assessed.

TABLE 1.

Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria1

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| DF intervention studies: | DF intervention studies: |

| 1) Published in English between January 1990 and December 2018. | 1) Population with history of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, or acute inflammatory diseases. |

| 2) Assessed the metabolic effect of DF by comparing to a control arm or baseline measurements. | 2) Combined other interventions (i.e., weight loss, low-fat diet, medications). |

| 3) Measured fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, CRP, IL-6, LDL-C, HDL-C, TC, TG, or postprandial glucose or insulin AUC after an OGTT. | 3) DF source is of low purity, as in <50% total DF based on dry weight. |

| 4) Normal weight, overweight, and/or obese adult population (mean age: 18–64 y). | 4) Insufficient data available on DF used, including source, purity, and/or dose. |

| 5) Intervention duration ≥2 wk. | 5) DF effect data is insufficient or missing for either the baseline or the control arm. |

CRP, C-reactive protein; DF, dietary fiber; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; OGTT, oral-glucose-tolerance test; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Search strategy

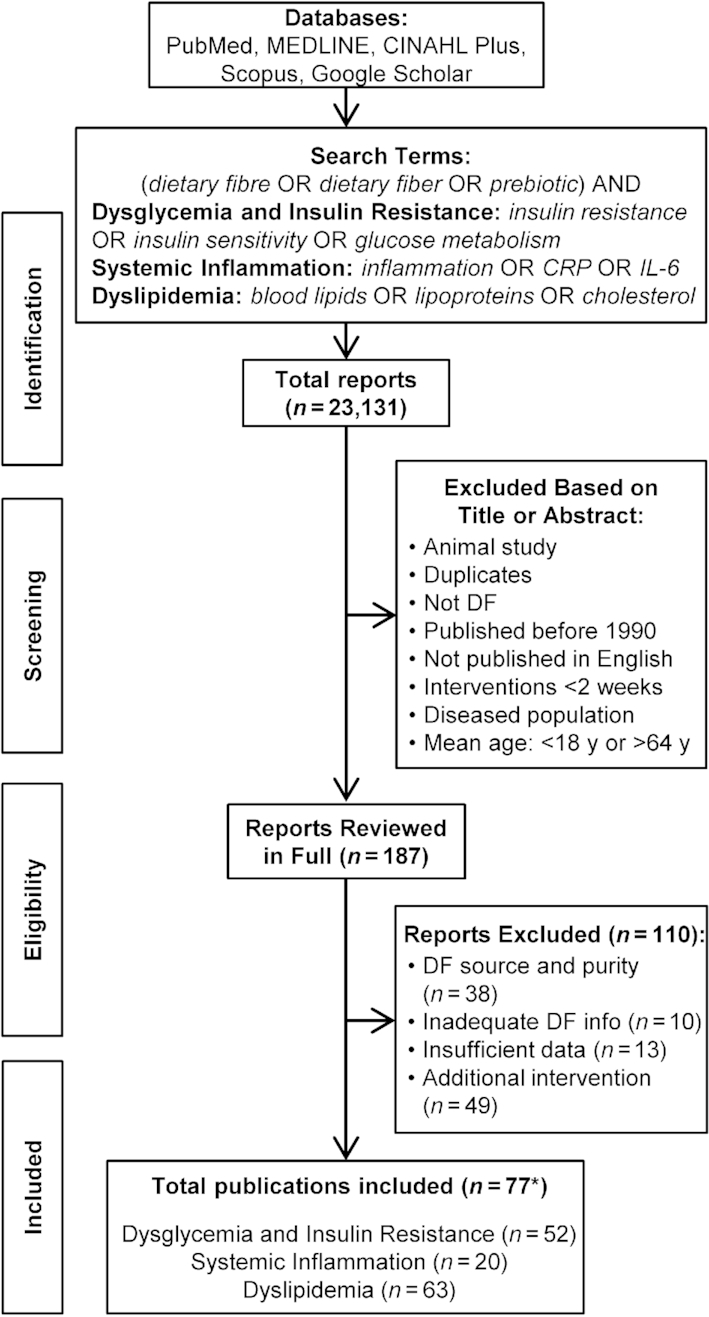

The databases PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Scopus, and Google Scholar were used to conduct a systematic literature search, as outlined in Figure 1. The selected search terms were as follows: (“dietary fibre” OR “dietary fiber” OR “prebiotic”) AND (“insulin resistance” OR “insulin sensitivity” OR “glucose metabolism”; “inflammation” OR “CRP” OR "IL-6"; “blood lipids” OR “lipoproteins” OR “cholesterol”). Two authors (AMA and ECD) completed the initial searches independently in May 2016, screening studies published from January 1990 onward, and all disagreements were resolved through discussions. Identified publications were included or excluded based on their title and/or abstract using selection criteria, and duplicate publications were removed. The remaining publications were reviewed in full and were assessed against the selection criteria to determine eligibility. The reference lists of eligible articles were screened for additional publications not identified in the initial searches. These publications were also reviewed in full and assessed using the same selection criteria. An updated search was conducted in December 2018 to include studies published since May 2016, and the same search strategy was used.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of article search and selection process. The literature search was first conducted during May 2016, and included all studies published from January 1990 onward. An updated literature search was conducted in December 2018. *Includes two articles that analyzed the same subject population but performed different analyses. CRP, C-reactive protein; DF, dietary fiber; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data extraction

One author (AMA) extracted the data, which included information on the study population (mean age, mean BMI, population characteristics), the intervention (study design, duration), the DF supplement (type, dose, purity), the placebo (type, dose), and whether the DF had a statistically significant effect on the immunometabolic markers when compared with baseline values and/or the placebo. For studies that did not report the actual amount of DF administered, the exact dose of DF was determined using the DF content of the supplement reported online. To ensure accuracy, 2 authors not involved in the initial data extraction (ECD and JVT) reviewed the data and any discrepancies were resolved through discussions.

Risk of bias quality assessment

Methodological quality was assessed for each publication according to the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias assessment tool (26). Two authors (AMA and ECD) completed this assessment independently and all discrepancies were resolved through discussions.

Data stratification

Since different DF types and doses were often compared in the same study, we considered individual treatment arms within studies as separate interventions. In order to synthesize the findings from each study, the effect of DF within each intervention arm was categorized based on either a statistically significant difference relative to baseline or against placebo (α = 0.05, P <0.05).

Interventions were stratified based on DF dose, DF physicochemical properties, intervention duration, and the placebo used in order to characterize how these variables influenced the effects of DF supplementation. Three categories were used for DF dose: ≤10.0 g, 10.1–20.0 g, and ≥20.1 g. DFs were categorized based on their described physicochemical properties as insoluble and nonviscous [consisting only of resistant starches; (RSs)], soluble and nonviscous (includes DFs that show a low increase in viscosity when dissolved), soluble and viscous, and mixed plant cell wall (MPCW) DFs (henceforth referred to as RS, nonviscous, viscous, and MPCW, respectively) using information provided in the publications or studies that characterized similar DF products; for example, corn bran hemicellulose (31) and rhubarb stalk DF (32). MPCW, as defined by the FDA, refers to an isolated DF ingredient that is comprised of 2 or more plant cell wall DF types and, thus, potentially 2 or more of the described physicochemical properties (i.e., insoluble, nonviscous, and viscous), along with other compounds, like minerals or phytochemicals, depending on the isolation method (33). If an intervention arm contained a mixture of nonviscous and viscous DF types (e.g., acacia gum and isolated pectin), then it was categorized as viscous. We focused the characterization of DF physicochemical properties solely on solubility and viscosity, as these characteristics have been attributed to health benefits of DF (18). Fermentability, which is also a key physicochemical property of DF, was not assessed, as it was not studied in most publications and remains poorly described for many DFs (34). Intervention arms were also stratified into 1 of 3 categories based on their intervention duration: 2–4 wk, 5–12 wk, and ≥13 wk. Finally, placebos were stratified into 1 of 3 categories. The first was “digestible carbohydrates,” which were supplemented in powder form (e.g., maltodextrin that participants mixed into food/drink) or were added to either juice or a sugar-sweetened beverage (e.g., fruit juice with maltodextrin compared with fruit juice with DF). The second was “vehicle,” which were the food matrices used in the intervention arm without the isolated DF (e.g., bread rolls, bagels). The third was “inert,” which were either nondigestible carbohydrates, such as microcrystalline cellulose, or drinks that were either unsweetened or contained artificial sweeteners, both of which would resist digestion and absorption and likely have minimal to no effect on the assessed markers. Although artificial sweeteners have been shown to influence glucose metabolism indirectly by acting on the gut microbiota (35), their effects on the reviewed immunometabolic markers are controversial (36).

We conducted a separate analysis with placebo-controlled interventions that reported significant effects to the immunometabolic markers assessed in order to determine to what degree the placebo accounted for the effect of DF on these markers. If raw data were not reported for either the intervention or placebo arms (i.e., presented only in figures), then these studies were excluded from this analysis as we could not quantify the effect of the placebo. For each intervention arm included in this analysis, the change relative to baseline in the intervention arm was subtracted from that in the placebo arm to obtain the total difference in effect between the arms (∆P − ∆DF). The change relative to baseline in the intervention and placebo arms were then both divided by ∆P − ∆DF and multiplied by 100  to calculate the percent of the effect attributable to the DF and to the placebo, respectively. No effect (0%) was attributable to the placebo if there was no change in the placebo relative to baseline and there was a significant difference in the DF group when compared with the placebo, or if a significant effect was only reported in the DF group when compared with baseline (and not to placebo).

to calculate the percent of the effect attributable to the DF and to the placebo, respectively. No effect (0%) was attributable to the placebo if there was no change in the placebo relative to baseline and there was a significant difference in the DF group when compared with the placebo, or if a significant effect was only reported in the DF group when compared with baseline (and not to placebo).

Results

Selection of interventions

A PRISMA flow chart of the overall search strategy and results is depicted in Figure 1. In total, 23,131 publications were identified, with 187 remaining after duplicates were removed and titles/abstracts were screened. After full text review, 110 additional articles were removed based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. These included 12 publications describing placebo-controlled studies that reported DF effects relative to placebo without reporting baseline data, and this information could not be obtained from the authors (37–46). These publications were removed since a digestible carbohydrate was used as the placebo, and it was not possible to assess the degree to which an adverse effect of the placebo contributed to significant differences.

Ultimately, 77 publications were included describing 106 intervention arms that supplemented isolated or synthetic DFs (>50% DF on a dry weight basis). Of the 77 publications, 54 described randomized controlled trials (47–100), of which 14 had >1 DF intervention arm (76–80, 82–88). There were 4 publications where a standardized background diet was consumed in both arms with and without the DF (89–91, 97), 3 publications where the control arm received no dietary intervention (93–95), and 1 publication that used inulin as a nonviscous control (88). Two publications were controlled but not randomized (101, 102); in addition, 20 studies had no control arm. Of these, 14 publications used a single-arm study design (103–116), whereas the remaining 6 publications employed either a parallel-arm or crossover study design to compare different DF doses (117) or types (118, 119), or to compare a DF to an intervention not included in this review [such as a probiotic (120), a high-DF diet (121), or a lower purity DF (122)]. Finally, 1 publication was comprised of 4 individual substudies: 3 were randomized placebo-controlled trials and 1 was a randomized crossover study without a placebo (123). Of the 77 eligible publications, 52 assessed markers of dysglycemia and/or insulin resistance, 20 assessed markers of systemic inflammation, and 63 assessed markers of dyslipidemia. Information on intervention arms that reported a significant effect is provided in Table 2, with information on all reviewed intervention arms provided in Supplemental Tables 1–3.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of studies reporting a significant effect of DF supplementation on immunometabolic markers in healthy adults1

| Reference | Study design | n | Study population characteristics | Age,2 y | Duration, wk | Control | Fiber type | Dose,3 g/d | Fiber properties | Marker(s) affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cossack, 1991 (114) | Single-arm | 10 | Hypercholesterolemic | 53 ± 8 | 5 | None | Sugar beet fiber | 26.6 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC, TG |

| Kawatra, 1991 (110) | Single-arm | 20 | Overweight | 30–50 | 6 | None | Guar gum | 12.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| Lampe, 1991 (76) | R, crossover (1.43 wk)4 | |||||||||

| Fiber | 32 | Healthy | 27.1 ± 2.1 | 3 | No DF | Mixed vegetable fiber | 10.0 | MPCW | ↓ TG | |

| Fiber | 34 | Mixed vegetable fiber | 30.0 | MPCW | ↓ TC, TG | |||||

| Fiber | 15 | Sugar beet fiber | 30.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC, TG | |||||

| Spiller, 1991 (122) | Crossover (0 wk) | 13 | Hypercholesterolemic | 62 ± 3.0 | 3 | None | Guar gum | 11.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| Haskell, 1992 (123) | R, crossover (0 wk) | 14 | Hypercholesterolemic | 52.5 ± 10.8 | 4 | None | Guar gum | 10.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| WSDF mixture | 15.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |||||||

| R, DB, parallel | ||||||||||

| Fiber | 12 | Hypercholesterolemic | 56.3 ± 9.5 | 4 | No DF | WSDF mixture | 5.0 | Viscous | ↔ | |

| Fiber | 13 | 56.3 ± 9.5 | WSDF mixture | 10.0 | Viscous | ↔ | ||||

| Fiber | 12 | 56.3 ± 9.5 | WSDF mixture | 15.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Control | 11 | 56.3 ± 9.5 | ||||||||

| Jensen, 1993 (96) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 14 | Hypercholesterolemic | 56 ± 9 | 4 | None | Acacia gum | 15.0 | Nonviscous | ↔ | |

| Fiber | 15 | 52 ± 9 | 4 | None | WSDF mixture | 15.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||

| Braaten, 1994 (47) | R, crossover (3 wk) | |||||||||

| Males | 9 | Hypercholesterolemic | 52 ± 2.6 | 4 | Maltodextrin | β-glucan (oat) | 5.8 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC, TG | |

| Females | 10 | 56 ± 1.3 | ||||||||

| Sandström, 1994 (90) | R, crossover (2 wk) | 11 | Healthy | 23 | 2 | No DF | Pea fiber | 20.0 | MPCW | ↓TG |

| Arvill, 1995 (48) | R, DB, crossover (2 wk) | 63 | Hypercholesterolemic | 47 ± 8.2 | 4 | Corn starch | Konjac glucomannan | 3.87 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC, TG |

| Goel, 1997 (115) | Single-arm | 10 | Hypercholesterolemic | 44 ± 2.9 | 4 | None | Rhubarb stalk fiber | 20.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| Brighenti, 1999 (101) | Crossover (0 wk) | 12 | Healthy | 23.3 ± 0.5 | 4 | No DF | Inulin | 9.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ TC, TG |

| Jackson, 1999 (59) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 27 | Hypercholesterolemic | 52.6 ± 8.6 | 8 | Maltodextrin | Inulin | 10.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ TG | |

| Control | 27 | 51.9 ± 10.5 | ||||||||

| Nicolosi, 1999 (116) | Single-arm | 15 | Hypercholesterolemic, | 51 ± 7 | 8 | None | β-glucan (yeast) | 15.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| obese | ↑ HDL-C | |||||||||

| Vidal-Quintanar, 1999 (106) | Single-arm (subgroup analysis) | 12 | Hypercholesterolemic | 39.5 ± 8.8 | 6 | None | LTMH fiber | 32.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| 11 | Healthy | 30.2 ± 7.6 | LTMH fiber | 32.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Zunft, 2001 (113) | Single-arm | 47 | Hypercholesterolemic | 54.8 ± 9.9 | 8 | None | Carob fiber | 15.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| Gallaher, 2002 (104) | Single-arm | 21 | Overweight | 28.9 ± 9.8 | 4 | None | Chitosan, konjac | 2.36 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| Zunft, 2003 (70) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 29 | Hypercholesterolemic | 55 ± 10 | 6 | No DF | Carob fiber | 15.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |

| Control | 29 | 53.8 ± 12 | ||||||||

| Marett, 2004 (77) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 18 | Healthy | 29 | 26 | Rice starch | Arabinogalactan (larch) | 8.4 | Nonviscous | ↓ glucose | |

| Fiber | 19 | Rice starch | Arabinogalactan | 8.4 | Nonviscous | ↓ glucose | ||||

| Control | 17 | (tamarack) | ||||||||

| Park, 2004 (92) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 12 | Overweight/obese | 42.3 ± 3.1 | 3 | Corn starch | RS type 3 | 24.0 | Insoluble | ↓ glucose, | |

| Control | 13 | 43.6 ± 2.8 | LDL-C, TC | |||||||

| Hall, 2005 (97) | R, SB, crossover (4 wk) | 38 | Healthy | 41.0 ± 1.9 | 4 | Low DF diet | Lupin kernel fiber | 22.25 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| Garcia, 2006 (99) | R, SB, crossover (6 wk) | 11 | Overweight/obese, IGT | 55.5 ± 6.2 | 6 | No DF | Arabinoxylan (wheat) | 12.2 | Viscous | ↓ glucose, TG |

| Yoshida, 2006 (98) | R, DB, crossover (4 wk) | 16 | Healthy | 55.2 ± 6.9 | 3 | No DF | Glucomannan | 10.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC |

| King, 2007 (121) | R, crossover (3 wk)4 | 17 | Obese, hypertensive | 38.3 ± 1.2 | 3 | DASH diet | Psyllium | 30.0 | Viscous | ↓ CRP |

| 18 | Lean, normotensive | |||||||||

| Queenan, 2007 (100) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 35 | Hypercholesterolemic | 44.5 ± 2.2 | 6 | Dextrose | β-glucan (oat) | 6.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |

| Control | 40 | 45.3 ± 2.0 | ||||||||

| Ganji, 2008 (105) | Single-arm (subgroup analysis) | Hypercholesterolemic | ||||||||

| 8 | Premenopausal | 34.6 ± 11.5 | 6 | None | Psyllium | 12.9 | Viscous | ↔ | ||

| 11 | Postmenopausal | 52.9 ± 2.8 | Psyllium | 12.9 | Viscous | ↓ TC | ||||

| Pérez-Jiménez, 2008 (93) | R, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 34 | Hypercholesterolemic, healthy | 35.5 ± 11.8 | 16 | No treatment | Grape antioxidant | 5.25 | MPCW | ↓ glucose, TC | |

| Control | 9 | 34.6 ± 12.4 | Dietary fiber | |||||||

| Smith, 2008 (118) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 45 | Hypercholesterolemic | 44.1 ± 13 | 6 | None | LMW β-glucan (barley) | 6.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ CRP, LDL-C | |

| Fiber | 45 | 45.1 ± 14 | HMW β-glucan (barley) | 6.0 | Viscous | ↔ | ||||

| Maki, 2009 (79) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 16 | Hypercholesterolemic | 58.9 ± 3.2 | 4 | No DF | HPMC (high viscosity) | 3.0 | Viscous | ↔ | |

| Fiber | 17 | 55.7 ± 3.1 | HPMC (low viscosity) | 5.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Fiber | 32 | 53.2 ± 2.8 | HPMC (high viscosity) | 5.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Fiber | 29 | 58.6 ± 1.9 | HPMC (low viscosity) | 10.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Fiber | 15 | 56.7 ± 2.1 | HPMC (moderate viscosity) | 10.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Fiber | 27 | 55.1 ± 1.9 | HPMC (moderately high viscosity) | 10.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Control | 29 | 57.3 ± 2.5 | ||||||||

| Reppas, 2009 (80) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 20 | Hypercholesterolemic | 41.6 | 6 | No DF | HPMC (high viscosity) | 5.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |

| Fiber | 10 | HPMC (high viscosity) | 15.0 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |||||

| Control | 10 | |||||||||

| Li, 2010 (55) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 60 | Overweight | 30.4 ± 4.3 | 12 | Maltodextrin | NUTRIOSE | 28.9 | Nonviscous | ↓ glucose, | |

| Control | 60 | 31.6 ± 4.1 | HOMA-IR, TC | |||||||

| LDL-C, ↑ HDL-C | ||||||||||

| Reimer, 2010 (54) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 27 | Healthy | 32.3 ± 10.3 | 3 | Skim milk | PolyGlycopleX | 8.7 | Viscous | ↓ HOMA-IR | |

| Control | 27 | 30.9 ± 10.8 | powder | |||||||

| Ruiz-Roso, 2010 (56) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 43 | Hypercholesterolemic | 42.9 ± 9.5 | 4 | Dextrose | Carob fiber | 8.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC, TG | |

| Control | 45 | 44.1 ± 9.9 | ↑ HDL-C | |||||||

| Russo, 2010 (52) | R, DB, crossover (8 wk) | 15 | Healthy | 18.8 ± 0.7 | 5 | No DF | Inulin | 11.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ glucose, |

| HOMA-IR, TG | ||||||||||

| ↑ HDL-C | ||||||||||

| Solà, 2010 (51) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 101 | Hypercholesterolemic | 54.2 ± 9.9 | 8 | MCC | Psyllium | 11.5 | Viscous | ↓ insulin, | |

| Control | 108 | 55.5 ± 11.2 | HOMA-IR | |||||||

| Lyon, 2011 (88) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber (M) | 15 | Healthy | 38.1 ± 7.2 | 15 | Inulin (low | PolyGlycopleX | 13.1 | Viscous | ↔ | |

| Fiber (F) | 15 | 34.7 ± 10.4 | viscous control) | PolyGlycopleX | 13.1 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |||

| Control (M) | 13 | 38.8 ± 7.1 | ||||||||

| Control (F) | 17 | 37.1 ± 10.8 | ||||||||

| Pal, 2011 (57) | R, SB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 16 | Overweight/obese | 41.3 ± 2.3 | 12 | Breadcrumbs | Psyllium | 29.7 | Viscous | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |

| Control | 15 | 44.8 ± 1.6 | ||||||||

| Hashizume, 2012 (58) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 15 | Metabolic syndrome | 60.1 ± 8.9 | 12 | No DF | Resistant maltodextrin | 27.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ glucose, | |

| Control | 15 | 61.2 ± 11.6 | HOMA-IR, | |||||||

| TC, TG | ||||||||||

| Gato, 2013 (84) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 13 | Hypercholesterolemic | 40.6 ± 1.9 | 12 | No DF | Persimmon fiber | 9.0 | MPCW | ↓ TC | |

| Fiber | 13 | 36.4 ± 1.8 | Persimmon fiber | 15.0 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC | ||||

| Control | 14 | 36.6 ± 1.8 | ||||||||

| Reimer, 2013 (61) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 28 | Abdominal adiposity | 20–65 | 14 | Rice flour | PolyGlycopleX | 13.1 | Viscous | ↓ IL-6, glucose, glucose AUC | |

| Control | 28 | 20–65 | ||||||||

| Fechner, 2014 (91) | R, DB, crossover (2 wk) | 52 | Hypercholesterolemic | 46.9 ± 3.2 | 4 | No DF | Lupin fiber | 21.7 | MPCW | ↓ CRP, LDL-C, TC, TG |

| Citrus fiber | 23.1 | MPCW | ↓ LDL-C, TC | |||||||

| Brahe, 2015 (64) | R, SB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 19 | Obese, postmenopausal | 60.6 ± 6.4 | 6 | No DF | Flaxseed mucilage | 10.0 | MPCW | ↓ insulin AUC | |

| Control | 20 | 58.5 ± 5.3 | ||||||||

| Urquiaga, 2015 (94) | R, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 25 | Metabolic syndrome | 44.5 ± 9.3 | 16 | No treatment | Wine grape pomace | 10.0 | MPCW | ↓ glucose, insulin AUC | |

| Control | 13 | 43.1 ± 8.4 | ||||||||

| Dainty, 2016 (66) | R, DB, crossover (4 wk) | 24 | Overweight/obese | 55.3 ± 1.6 | 8 | No DF | RS type 2 (hi-maize) | 25.0 | Insoluble | ↓ insulin, insulin |

| AUC, HOMA-IR | ||||||||||

| Kapoor, 2016 (103) | Single-arm, pilot | 6 | Healthy | 46.3 ± 2.9 | 52 | None | Partially hydrolyzed guar gum | 14.4 | Nonviscous | ↓ CRP, LDL-C |

| ↑ HDL-C | ||||||||||

| Nasir, 2016 (111) | Single-arm | 10 | Prediabetic | 35–60 | 16 | None | Acacia gum | 10.0 | Nonviscous | ↓ glucose |

| Lambert, 2017 (68) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 22 | Overweight/obese | 44 ± 15 | 12 | No DF | Yellow pea hull fiber | 13.8 | MPCW | ↓ glucose AUC | |

| Control | 22 | 44 ± 15 | ||||||||

| Pal, 2017 (86) | R, DB, parallel | |||||||||

| Fiber | 39 | Overweight/obese | 49.9 ± 11.0 | 12 | Rice flour | Psyllium | 12.9 | Viscous | ↓ insulin, HOMA-IR | |

| Fiber | 43 | 47.9 ± 12.1 | PolyGlycopleX | 13.1 | Viscous | |||||

| Control | 45 | 49.8 ± 11.8 | ↑ HDL-C | |||||||

| Martínez-Maqueda, 2018 (95) | R, crossover (4 wk) | 49 | Metabolic syndrome | 42.6 ± 1.6 | 6 | No treatment | Wine grape pomace | 8.0 | MPCW | ↓ insulin, HOMA-IR |

| Urquiaga, 2018 (102) | Crossover, (4 wk) | 27 | Metabolic syndrome | 43.6 ± 11.2 | 4 | No DF | Wine grape pomace | 3.5 | MPCW | ↓ HOMA-IR |

CRP, C-reactive protein; DASH, dietary approaches to stop hypertension; DB, double-blinded; DF, dietary fiber; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; HMW, high molecular weight; HPMC, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; LTMH, lime-treated maize husk; LMW, low molecular weight; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; MCC, microcrystalline cellulose; MPCW, mixed plant cell wall; No DF, the control was the same product received by the treatment group but without the dietary fiber added; R, randomized; RS, resistant starch; SB, single-blinded; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WSDF, water soluble dietary fiber mixture of psyllium, pectin, guar gum, and locust bean gum; ↓, significant decrease; ↑, significant increase; ↔, no significant change.

Mean age is presented as they were in the original articles (as mean ± SD, mean ± SEM, or a range).

DF dose was corrected for the purity of the fiber.

Washout period in weeks of crossover studies included in parentheses.

DF dose was based on individual energy intake; mean of group is provided here.

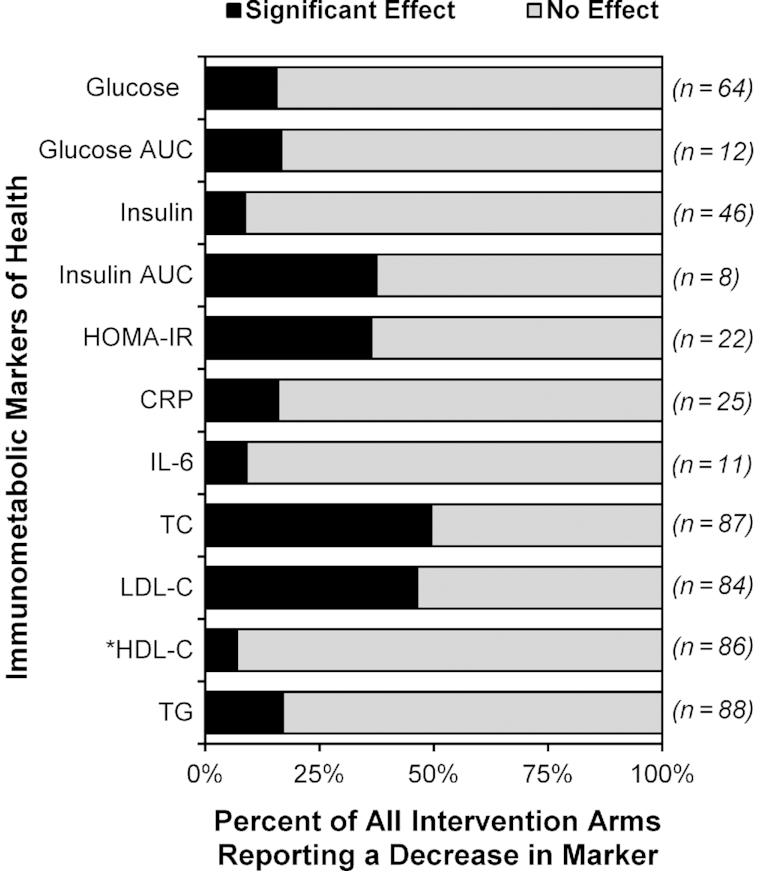

Influence of DF on immunometabolic markers

There were substantial differences in the efficacy of DF supplementation in improving immunometabolic markers. Although 36–49% of the treatment arms reported a significant reduction to insulin AUC, HOMA-IR, TC, and LDL cholesterol, <20% of interventions led to improvements in CRP, IL-6, glucose, insulin, glucose AUC, HDL cholesterol, and TG (Figure 2, Table 2). Similar findings were obtained when only higher quality studies (i.e., those without a ‘high’ risk of bias) (Supplemental Figure 1A) or those whose study population had risk factors for metabolic diseases (e.g., overweight/obese, hypercholesterolemic, and/or prediabetic subjects) (Supplemental Figure 1B) were included. Since only 1 intervention arm out of 11 reported a significant decrease to IL-6, we did not include this marker in the stratification analyses described below.

FIGURE 2.

Reported effects of DF supplementation on immunometabolic markers in healthy adults. Intervention arms were considered to have a significant decrease in the assessed marker relative to baseline and/or placebo if the reported P value was <0.05. Data are reported as a percentage of all intervention arms. *Considered to have a significant increase in HDL cholesterol rather than decrease. CRP, C-reactive protein; DF, dietary fiber; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

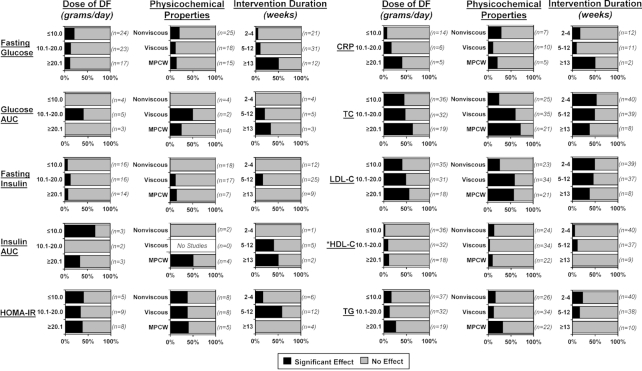

Effect of DF stratified by dose

Out of the 106 interventions, 43 (41%) supplemented ≤10 g/d of DF, which was almost twice as many as those that supplemented ≥20.1 g/d (23%, 24 arms). There were only 3 studies that supplemented >30 g/d of DF: 32 g/d of lime-treated maize husk DF was supplemented for 6 wk (106), 45 g/d of RS type 2 was supplemented for 12 wk (75), and 55 g/d of oligofructose was supplemented in a 5-wk dose-escalation study (108).

Stratification of the intervention arms by dose revealed that some markers were more likely to be improved after high doses of DF were supplemented. The influence of dose was most pronounced for CRP, where 40% (2 arms) of the interventions that provided ≥20.1 g/d DF showed a significant reduction, whereas only 10% (2 arms) below this dose reported a significant effect (Figure 3). For psyllium specifically, there were 4 intervention arms that supplemented between 6 and 30 g/d, and only 30 g/d significantly reduced CRP (121). An influence of dose was also observed for TC and LDL cholesterol, where 63% and 56% of intervention arms (12 and 10 arms, respectively) providing ≥20.1 g/d DF showed significant improvements, whereas only 44% and 40% of intervention arms (16 and 14 arms, respectively) that supplemented ≤10 g/d DF showed benefits (Figure 3). Higher DF doses also appeared to improve TG (Figure 3), with 27% of interventions that supplemented ≥20.1 g/d DF reporting a significant reduction compared with 14% of interventions that used lower doses. Overall, the findings suggest that higher doses of DF are more likely to improve several immunometabolic markers. However, studies that supplement high DF doses are severely underrepresented in the literature, and more research, especially dose-response studies, are needed to draw concrete conclusions.

FIGURE 3.

Reported effects of DF supplementation on immunometabolic markers in healthy adults when stratified by DF dose, DF physicochemical properties, and intervention duration. Intervention arms were considered to have a significant effect on the assessed marker relative to baseline and/or placebo if the reported P value was <0.05. Data are reported as a percentage of all intervention arms that assessed these markers. DFs were categorized as soluble with minimal viscosity, soluble with high viscosity, and mixed plant cell wall DFs (nonviscous, viscous, and MPCW, respectively) using information provided in the publications themselves or studies that characterized similar DF products. Seven interventions supplemented a resistant starch, but only 2 reported significant effects to the markers: 25 g/d reduced insulin, insulin AUC, and HOMA-IR (66), and 24 g/d reduced glucose, TC, and LDL cholesterol (92). *Considered to have a significant increase in HDL cholesterol rather than decrease. CRP, C-reactive protein; DF, dietary fiber; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; MPCW, mixed plant cell wall; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Effect of DF stratified by physicochemical properties

The studies included in this review used a wide range of DF types with different physicochemical properties that can influence their physiological effects (124). Of these studies, 40% and 32% (42 and 34 arms) supplemented with viscous or nonviscous DFs, respectively. Of the remaining intervention arms, 22% (23 arms) supplemented MPCW DFs, whereas 7% (7 arms) supplemented an RS. Due to the small number of intervention arms, RSs were not included in the final stratification analyses, but are reported in Supplemental Tables 1–3.

Stratification of the findings by DF physicochemical properties suggested that they are relevant depending on the markers assessed. Although only 24% and 26% of intervention arms that supplemented nonviscous DFs reported a benefit for TC and LDL cholesterol, respectively, 60% and 59% of studies with viscous DFs reported a significant effect (Figure 3). Psyllium (51, 57), β-glucan (47, 100), and konjac or guar gums (48, 98, 104, 110, 122) were especially effective. In addition, MPCW DF types were equally as effective as viscous DFs (Figure 3). Further, 32% of MPCW DF intervention arms reported a significant reduction of TG, whereas only 12% of viscous and 15% of nonviscous DFs reported the same. The importance of DF physicochemical properties on the other immunometabolic markers was not conclusive due to the small number of studies.

Effect of DF stratified by intervention duration

The majority of studies employed short durations of DF supplementation, with almost half (47%, 50 arms) of the interventions being 2–4 wk, and only 11% (12 arms) being ≥13 wk. There was only 1 study that supplemented DF for a year, which was a single-arm pilot study (103), and 3 studies that supplemented DF for 6 mo (65, 77, 107).

Stratification of trials by intervention duration revealed that some markers were more likely to improve after a longer administration of DF. Of the interventions that were ≥13 wk, 50% (6 arms) showed a significant reduction in fasting glucose, whereas only 8% (4 arms) reported a significant effect when the duration was ≤12 wk (Figure 3). Similar findings were observed for CRP (Figure 3). Consuming DF for 2–4 wk did not result in any improvements in glucose AUC, insulin, or insulin AUC (Figure 3). In contrast, short interventions were just as efficacious as longer interventions for reducing TC and LDL cholesterol (Figure 3). These results suggest that while shorter intervention studies are sufficient for improving cholesterol metabolism, longer DF exposure may be necessary for improvements in markers of dysglycemia and systemic inflammation. However, interpretation of these findings warrants caution as very few intervention arms supplemented DF for ≥13 wk. Furthermore, out of the ≥13-wk intervention studies reporting a significant reduction of glucose or CRP, only 1 was assessed to have a ‘low’ risk of bias (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

The confounding effect of the placebo in DF interventions

Of the 50 placebo-controlled studies included, 54% (27 studies) used digestible carbohydrates as placebos that were either provided alone (e.g., corn starch, maltodextrin) or within a food matrix containing mainly simple carbohydrates (e.g., juice). An additional 36% (18 studies) of studies provided the placebo as a digestible food vehicle without the DF (e.g,. bagel, bread rolls), whereas only 10% (10 studies) used an inert, calorie-free placebo (e.g., cellulose, artificial sweeteners).

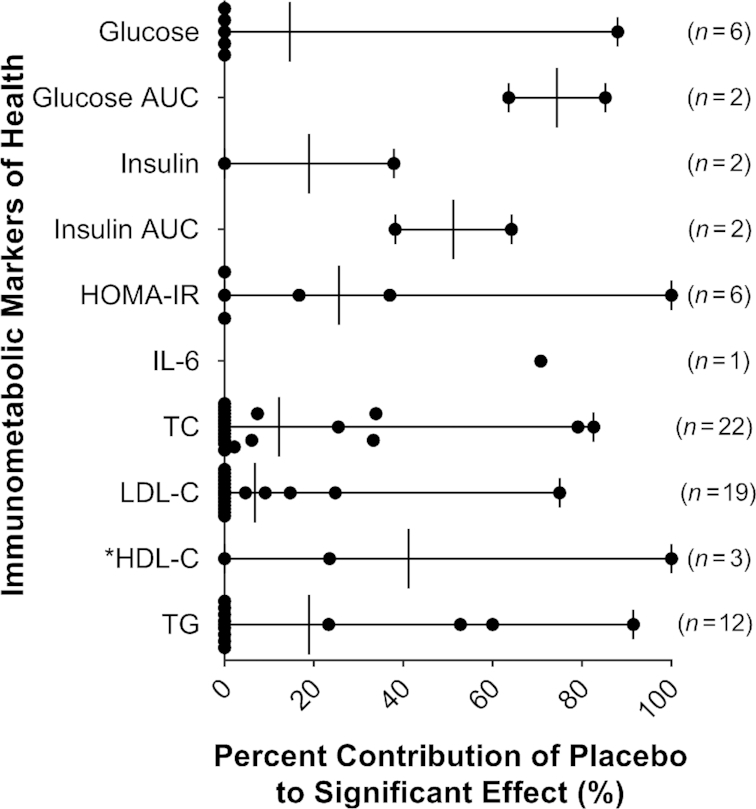

Of the 50 placebo-controlled studies, 28 saw benefits as a result of DF supplementation and reported raw baseline and postintervention data for both the intervention and placebo arms. An analysis of these intervention arms revealed that <15% of the improvements in glucose, TC, and LDL cholesterol could be attributed to the placebo, indicating that these findings were not confounded (Figure 4). In contrast, for IL-6, glucose AUC, and insulin AUC, more than half of the detected improvements (71%, 74%, and 51%, respectively) were attributable to the placebo exerting a detrimental effect on the marker. One can, therefore, conclude that the placebo types used were not inert and confounded the true effect of the DF supplement. These findings have implications for the design of placebo-controlled studies assessing the immunometabolic effects of DFs and their use in nutritional interventions.

FIGURE 4.

Contribution of the placebo to the perceived effect of DF on immunometabolic markers. The change relative to baseline was calculated and subtracted from the change reported by the placebo (i.e., ∆P − ∆DF). The change relative to baseline in each intervention arm and placebo were then both divided by this value and multiplied by 100  to calculate the percent of the effect attributable to DF supplementation and to placebo, respectively. *Considered to have a significant increase in HDL cholesterol rather than decrease. HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

to calculate the percent of the effect attributable to DF supplementation and to placebo, respectively. *Considered to have a significant increase in HDL cholesterol rather than decrease. HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

Discussion

The results from this systematic review revealed that the efficacy of isolated and synthetic DFs depends markedly on the immunometabolic endpoints assessed. Although HOMA-IR, insulin AUC, TC, and LDL cholesterol improved in around half of the interventions, CRP, IL-6, glucose, glucose AUC, insulin, HDL cholesterol, and TG did not show any effect in >80% of the interventions. These results are in agreement with other systematic reviews that reported reductions in LDL cholesterol (125–132), TC (128, 129, 131, 132), and HOMA-IR (133) from DF supplementation, whereas no effects were observed for CRP and IL-6 (6), fasting glucose and insulin (131), and HDL cholesterol and TG (128, 129, 132, 134). In contrast to our findings, 2 meta-analyses have reported significant reductions to fasting glucose (23, 133) and insulin (23) from viscous DF supplementation. However, these meta-analyses included intervention studies that assessed the effect of DF relative to a placebo, which may explain the discrepancy with our findings, especially given the potential confounding adverse effect of some placebos on these markers. Overall, our findings demonstrate that the effects of isolated and synthetic DFs as hitherto used in intervention studies are at best, inconsistent and, at worst, negligible, mainly improving TC and LDL cholesterol concentrations and insulin resistance, but not markers of dysglycemia and systemic inflammation.

These results are in agreement with a large body of research showing that the effects of DF supplementation are far less consistent than those reported in observational studies (6, 24, 135). This poses the important question: what causes this discrepancy? Physiological effects of DF may diminish or even be lost once they are isolated from the food matrix (5, 136–138). This concern is reflected in the FDA's regulatory definition of DF, which considers the physiological benefits of intrinsic and intact DFs in plants as established, while requiring experimental demonstration of the same for isolated and synthetic nondigestible carbohydrates (2, 33). It has been suggested that the benefits detected in observational studies may not be derived from DF, but rather from other food constituents (e.g., micronutrients) and bioactive compounds (e.g., phytochemicals) present in plants (139–141). However, the findings of our systematic review clearly support the ability of isolated and synthetic DFs to improve cholesterol concentrations and insulin resistance. Although there is indeed little effect on markers of dysglycemia and inflammation, our stratification analyses on DF dose, DF physicochemical properties, and intervention duration suggested that most studies do not utilize DF supplements to their fullest potential.

In terms of dose, we found that interventions that supplied ≥20.1 g/d of DF resulted in a higher proportion of interventions that resulted in significant improvements for several markers, including cholesterol concentrations and CRP. Although based on a small number of interventions, our findings are consistent with other studies. Supplementation of an oat bran, rye bran, and sugar beet fiber mixture at a dose of 48 g/d of DF significantly reduced CRP, whereas a dose of 30 g/d was ineffective (142). In addition, a diet composed of green leafy vegetables, fruit, and nuts providing 143 g/d of DF significantly reduced LDL cholesterol compared with a low-fat therapeutic diet (143). Further, a recent series of meta-analyses reported that the daily consumption of 25–29 g of DF generated the greatest benefits on a range of clinical outcomes when compared with lower doses, and dose response curves suggested that additional benefits would result from even higher intakes (5), a conclusion echoed in the Institute of Medicine's Dietary Reference Intakes (144).

Considering the importance of the physicochemical properties of DF, we found viscous DFs to be especially effective at reducing cholesterol concentrations. Viscous DFs can decrease cholesterol concentrations by binding bile acids that have been secreted into the small intestine, enhancing their excretion. This leads to an increase in bile acid synthesis, which lowers blood cholesterol concentrations (17). Interestingly, our findings show that MPCW DFs improve cholesterol concentrations as consistently as viscous DFs. The mechanisms behind the cholesterol-lowering effect of MPCW DFs are not as well understood as for viscous DFs. However, these MPCW DFs can contain insoluble hemicelluloses, as well as lignin and phytochemicals, all of which have been shown to bind bile acids and cholesterol and increase their excretion (145–148).

In regards to intervention duration, it is conceivable that DF-induced bile acid excretion would not require extensive time to reduce blood cholesterol concentrations, since inhibiting the reabsorption of cholesterol has a direct effect on metabolic processes and outcomes (17, 149). This could explain why short intervention durations were sufficient to improve cholesterol markers. In contrast, improvements to dysglycemia and inflammation appeared to require longer study durations. Although the mechanisms by which benefits in these markers arise are not completely understood, they likely require physiological statuses of responsible tissues and cells (e.g., β-cells, adipocytes, hepatocytes, myocytes, and various immune cell types) to change (150), which would require more time.

Our analysis also revealed that more than half of the placebo-controlled trials used digestible carbohydrates as a placebo, which have well-documented detrimental effects on immunometabolic markers (29, 30). A majority of the apparent beneficial effects of DF on IL-6, glucose AUC, and insulin AUC were indeed attributable to the placebo not being inert rather than the DF itself, which was recognized in 1 of the reviewed publications (61). These findings imply that DFs may not directly benefit dysglycemia or systemic inflammation per se, but instead have no detrimental effect in contrast to digestible carbohydrates. Similar observations have also been made in intervention studies with whole grains (151, 152) and a prebiotic in children (153), where benefits were driven primarily by the digestible carbohydrate controls having a detrimental effect, especially concerning inflammation. Given the difficulty of selecting a placebo for nutritional studies (28), it is imperative to compare treatments not only to the placebo, but also to the baseline in order to assess the potential confounding effects of the placebo.

We believe our findings provide some important insights on the role of DF in human health. The influence of DF dose, DF physicochemical properties, and intervention duration, as well as the confounding effects of placebos, which are all insufficiently considered in research studies (18, 34, 154, 155), provide a potential explanation for why intervention studies are more inconsistent when compared with observational studies. Although the latter inherently assess the long-term consumption of food matrices comprised of complex mixtures of DFs, having a range of physicochemical properties at doses that reflect a high habitual intake (>20 g/d) (5, 10, 156), intervention studies typically assess the effect of 1 or 2 DF types with a limited range of physicochemical properties at varying doses and often shorter durations. Using a limited number of DF types likely contributes to the interindividual variation of responses in intervention studies, as the ability of the gut microbiota to ferment specific DF chemistries into beneficial metabolites differs among individuals (157, 158). In addition, observational studies assess the effect of diets rich in whole foods relative to diets high in refined foods, and findings could, at least in part, be driven by the detrimental effect of these foods. Therefore, despite the high proportion of intervention trials with no significant effect, DF might still be an active constituent of whole foods, but its effects might be reduced or lost due to between-study and intersubject heterogeneities (23), and how DF supplements are applied.

In this respect, our findings suggest that DF supplementation could potentially be improved by implementing a more targeted and specific application. Most intervention studies in the literature supplement DFs at doses that are insufficient for reliable benefits (20, 159) and are also too low from an evolutionary perspective, given that humans evolved consuming a diet that contained over 100 g/d of DF (22, 143, 160). Further, physicochemical properties of DFs are often not considered or insufficiently chemically characterized, thus limiting the ability to draw clear conclusions across the full breadth of DF types (34, 154, 155). Third, mixtures of DF types that mimic variation in the diet may overcome interindividualized physiological responses through a diversified effect on the gut microbiota. Finally, isolated and synthetic DFs may be most beneficial, especially for dysglycemia and systemic inflammation, when they replace digestible carbohydrates in foods rather than being provided as a supplement in addition to the habitual diet. Based on the findings of this review (Figure 3 and Table 2), we have compiled recommendations on how future research should consider applying DFs in a more targeted and marker-specific way (Table 3). Several of these recommendations are, however, based on a limited number of studies. Well-controlled human trials with longer durations are needed that assess the effects of well-characterized DFs at relevant doses (and optimally also assess dose responses) on specific clinical outcomes predictive of health to substantiate whether a targeted approach improves the efficacy of DF supplementation (154, 159, 161, 162).

TABLE 3.

Summary of findings and conclusions for a more targeted use of DF supplements1

| Immunometabolic marker | DF dose | DF physicochemical properties | Intervention duration | Placebo | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysglycemia and insulin resistance | |||||

| Glucose | No effect of dose detected. | No clear pattern. | Longer durations of ≥13 wk resulted in an effect more often (61, 77, 93, 94, 111). | Placebo appeared not to confound findings. | Supplement DF for longer durations (≥13 wk). |

| Glucose AUC | Insufficient information available. | Insufficient information available. | Interventions ≤4 wk showed no effect. | Placebo had a strong confounding effect (61, 68). Inert compounds should be used. | Very limited information available, but interventions may need to be ≥5 wk. Given the negative effect of digestible CHO on hyperglycemia, benefits could be achieved by their replacement with DF. |

| Insulin | Little effect at any dose. | Little effect of any DF type. | Little effect with any intervention duration. | Insufficient data provided to determine the effect of the placebo. | DF supplementation, as currently used, does not appear to influence fasting insulin. |

| Insulin AUC | Insufficient information available. | Insufficient information available. | Insufficient information available. | Placebo had a strong confounding effect (64, 66). | Very limited information available. Given the negative effect of digestible CHO on hyperinsulinemia, benefits could be achieved by their replacement with DF. |

| HOMA-IR | No effect of dose detected. | No difference in DF type detected. | Durations between 5 and 12 wk resulted in an effect more often (51, 52, 58, 86, 95). | Placebo appeared not to confound findings. | Supplement DF for ≥5 wk. |

| Inflammation | |||||

| CRP | Little effect at doses ≤20 g/d; however, there was evidence of a dose response. Higher DF dose interventions resulted in an effect more often (91, 121). | Insufficient information available. | Little effect for durations <13 wk. Studies of ≥13 wk administration showed an effect more often (103). | No placebo-controlled interventions included in this review showed an effect. However, digestible CHO have been shown to induce inflammation (61, 151); therefore, inert compounds should be used. | Supplement higher doses of DF (>20 g/d) for longer durations (≥13 wk). Given the proinflammatory effect of digestible CHO, benefits could be achieved by their replacement with DF. |

| IL-6 | Insufficient information available. | Insufficient information available. | Insufficient information available. | Placebo had a detrimental effect that confounded the true effect of DF supplementation (61). Inert compounds should be used. | Overall, insufficient information is available to make recommendations. Further research needs to be conducted assessing the effect of replacing digestible CHO with DFs. |

| Dyslipidemia | |||||

| TC | Lower doses were sufficient to reduce this marker, but doses ≥20.1 g/d resulted in an effect more often (76, 91, 92, 97, 106). | Viscous and mixed plant cell wall DF types resulted in an effect more often (47, 56, 80, 91, 105). | Short intervention durations (2–4 wk) were sufficient to reduce this marker (56, 79, 91, 115, 122). | Placebo had little effect; overall, did not confound findings. | Supplement higher doses of DF (≥20.1 g/d) for 2–4 wk. Use viscous or mixed plant cell wall DFs. |

| LDL-C | Lower doses were sufficient to reduce this marker, but doses ≥20.1 g/d resulted in an effect more often (55, 57, 91, 97, 114). | Viscous and mixed plant cell wall DF types resulted in an effect more often (48, 51, 70, 84, 123). | Short intervention durations (2–4 wk) were sufficient to reduce this marker (56, 79, 98, 104, 122). | Placebo had little effect; overall, did not confound findings. | Supplement higher doses of DF (≥20.1 g/d) for 2–4 wk. Use viscous or mixed plant cell wall DFs. |

| HDL-C | Little effect at any dose. | Little effect of any DF type. | Little effect at any intervention duration. | Insufficient information available. | DF supplementation does not appear to increase HDL-C. |

| TG | Little effect at any dose, but doses ≥20.1 g/d resulted in an effect more often (58, 76, 91, 114). | Little effect of any DF type, but mixed plant cell wall DFs resulted in an effect more often (56, 76, 90, 91, 114). | Little effect with any intervention duration. | Insufficient data provided to determine the effect of the placebo. | DF supplementation, appears to effect TG minimally as currently used, but higher doses of mixed plant cell wall DFs may improve results. |

CHO, carbohydrates; CRP, C-reactive protein; DF, dietary fiber; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

A diet rich in plant-based whole foods is encouraged by dietary guidelines (163–165) and likely the best choice for optimal health (5, 166). However, society-wide consumption of DF-rich whole foods remains insufficient despite substantial efforts by educators and authorities, resulting in a “fiber gap” (2, 22, 167). DF supplements or foods enriched with DF have been proposed as alternatives to whole foods (22, 23), but the health benefits of these diet items have been questioned (5). The findings from this review suggest that supplementation of isolated and synthetic DFs, as currently practiced, is likely a viable strategy to target cholesterol concentrations and insulin resistance, but not markers of dysglycemia and inflammation. Benefits in the latter might be achievable if specific DFs, or mixtures thereof, are supplemented for longer durations and at higher doses, especially when they replace digestible carbohydrates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—JW and ECD: designed the research; JW, ECD, AMA, SJH, and JVT: developed the protocol; AMA and ECD: performed eligibility screening; AMA and ECD: performed data extraction; AMA and ECD: performed stratification analyses; AMA, JW, and ECD: wrote the initial manuscript; AMA and JW: had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: have read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

JW is a recipient of grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and JPI (healthy diet for a healthy life).

Author disclosures: AMA, ECD, JVT, and SJH, no conflicts of interest. JW has received research funding and consulting fees from industry sources involved in the manufacture and marketing of dietary fibers, and is a co-owner of Synbiotics Health, a developer of synbiotic products.

Supplemental Tables 1–3 and Supplemental Figure 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/advances/.

Abbreviations used: CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DF, dietary fiber; MPCW, mixed plant cell wall; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RS, resistant starch; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides.

References

- 1. Ludwig DS, Hu FB, Tappy L, Brand-Miller J. Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease. BMJ. 2018;361:k2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jones JM. CODEX-aligned dietary fiber definitions help to bridge the “fiber gap”. Nutr J. 2014;13:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dahl WJ, Stewart ML.. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Health Implications of Dietary Fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(11):1861–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Delcour JA, Aman P, Courtin CM, Hamaker BR, Verbeke K. Prebiotics, fermentable dietary fiber, and health claims. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Morenga LT. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):434–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buyken AE, Goletzke J, Joslowski G, Felbick A, Cheng G, Herder C, Brand-Miller JC. Association between carbohydrate quality and inflammatory markers: systematic review of observational and interventional studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(4):813–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Du H, van der A DL, Boshuizen HC, Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ, Halkjær J, Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Jakobsen MU, Boeing H et al.. Dietary fiber and subsequent changes in body weight and waist circumference in European men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(2):329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen J-P, Chen G-C, Wang X-P, Qin L, Bai Y. Dietary fiber and metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis and review of related mechanisms. Nutrients. 2018;10(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wei B, Liu Y, Lin X, Fang Y, Cui J, Wan J. Dietary fiber intake and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(6):1935–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yao B, Fang H, Xu W, Yan Y, Xu H, Liu Y, Mo M, Zhang H, Zhao Y. Dietary fiber intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose-response analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(2):79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The InterAct Consortium. Dietary fibre and incidence of type 2 diabetes in eight European countries: the EPIC-InterAct Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetologia. 2015;58(7):1394–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pereira MA, O'Reilly E, Augustsson K, Fraser GE, Goldbourt U, Heitmann BL, Hallmans G, Knekt P, Liu S, Pietinen P et al.. Dietary fiber and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(4):370–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Veronese N, Solmi M, Caruso MG, Giannelli G, Osella AR, Evangelou E, Maggi S, Fontana L, Stubbs B, Tzoulaki I. Dietary fiber and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(3):436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Y, Zhao LG, Wu QJ, Ma X, Xiang YB. Association between dietary fiber and lower risk of all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;181(2):83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deehan EC, Duar RM, Armet AM, Perez-Muñoz ME, Jin M, Walter J. Modulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome with nondigestible fermentable carbohydrates to improve human health. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5(5):1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kaczmarczyk MM, Miller MJ, Freund GG. The health benefits of dietary fiber: beyond the usual suspects of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and colon cancer. Metabolism. 2012;61(8):1058–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gunness P, Gidley MJ.. Mechanisms underlying the cholesterol-lowering properties of soluble dietary fibre polysaccharides. Food Funct. 2010;1(2):149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McRorie JW, McKeown NM.. Understanding the physics of functional fibers in the gastrointestinal tract: an evidence-based approach to resolving enduring misconceptions about insoluble and soluble fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(2):251–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Makki K, Deehan EC, Walter J, Bäckhed F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(6):705–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. King DE, Mainous AG, Lambourne CA. Trends in dietary fiber intake in the United States, 1999–2008. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deehan EC, Walter J.. The fiber gap and the disappearing gut microbiome: implications for human nutrition. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(5):239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson SV, Hannon BA, An R, Holscher HD. Effects of isolated soluble fiber supplementation on body weight, glycemia, and insulinemia in adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106(6):1514–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fuller S, Beck E, Salman H, Tapsell L. New horizons for the study of dietary fiber and health: a review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2016;71(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Higgins JP, Green S.. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Internet]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org

- 27. de Craen AJM, Kaptchuk TJ, Tijssen JGP, Kleijnen J. Placebos and placebo effects in medicine: historical overview. J R Soc Med. 1999;92(10):511–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Staudacher HM, Irving PM, Lomer MCE, Whelan K. The challenges of control groups, placebos and blinding in clinical trials of dietary interventions. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76(3):203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ludwig DS. The glycemic index physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287(18):2414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Augustin LSA, Franceschi S, Hamidi M, Marchie A, Jenkins AL, Axelsen M. Glycemic index: overview of implications in health and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):266S–73S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sugawara M, Suzuki T, Totsuka A, Takeuchi M, Ueki K. Composition of corn hull dietary fiber. Starch/Stärke. 1994;46(9):335–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goel V, Cheema SK, Agellon LB, Ooraikul B, McBurney MI, Basu TK. In vitro binding of bile salt to rhubarb stalk powder. Nutr Res. 1998;18(5):893–903. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Office of Nutrition and Food Labeling. The Declaration of Certain Isolated or Synthetic Non-digestible Carbohydrates as Dietary Fiber on Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels: Guidance for Industry. College Park (MD): Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration; 2018. Docket No: FDA-2018-D-1323. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Poutanen KS, Fiszman S, Marsaux CFM, Pentikäinen SP, Steinert RE, Mela DJ. Recommendations for characterization and reporting of dietary fibers in nutrition research. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(3):437–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss CA, Maza O, Israeli D, Zmora N, Gilad S, Weinberger A et al.. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514(7521):181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Plaza-Díaz J, Sáez-Lara MJ, Gil A. Effects of sweeteners on the gut microbiota: a review of experimental studies and clinical trials. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(suppl_1):S31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heijnen MLA, Van Amelsvoort JMM, Deurenberg P, Beynen AC. Neither raw nor retrograded resistant starch lowers fasting serum cholesterol concentrations in healthy normolipidemic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(3):312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Landin K, Holm G, Tengborn L, Smith U. Guar gum improves insulin sensitivity, blood lipids, blood pressure, and fibrinolysis in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56(6):1061–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Effertz ME, Denman P, Slavin JL. The effect of soy polysaccharide on body weight, serum lipids, blood glucose, and fecal parameters in moderately obese adults. Nutr Res. 1991;11(8):849–59. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pasman W, Wils D, Saniez MH, Kardinaal A. Long-term gastrointestinal tolerance of NUTRIOSE®FB in healthy men. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(8):1024–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gower BA, Bergman R, Stefanovski D, Darnell B, Ovalle F, Fisher G, Sweatt SK, Resuehr HS, Pelkman C. Baseline insulin sensitivity affects response to high-amylose maize resistant starch in women: a randomized, controlled trial. Nutr Metab. 2016;13:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Morel FB, Dai Q, Ni J, Thomas D, Parnet P, Fança-Berthon P. α-Galacto-oligosaccharides dose-dependently reduce appetite and decrease inflammation in overweight adults. J Nutr. 2015;145(9):2052–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robertson MD, Wright JW, Loizon E, Debard C, Vidal H, Shojaee-Moradie F, Russell-Jones D, Umpleby AM. Insulin-sensitizing effects on muscle and adipose tissue after dietary fiber intake in men and women with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3326–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cherbut C, Aube A-C, Mekki N, Dubois C, Lairon D, Barry J-L. Digestive and metabolic effects of potato and maize fibres in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 1997;77(1):33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Robertson D, Bickerton AS, Dennis L, Vidal H, Frayn KN. Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(3):559–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bodinham CL, Smith L, Wright J, Frost GS, Robertson MD. Dietary fibre improves first-phase insulin secretion in overweight individuals. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Braaten JT, Wood PJ, Scott FW, Wolynetz MS, Lowe MK, Bradley-White P, Collins MW. Oat β-glucan reduces blood cholesterol concentration in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48(7):465–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Arvill A, Bodin L.. Effect of short-term ingestion of konjac glucomannan on serum cholesterol in healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(3):585–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kohl A, Gögebakan Ö, Möhlig M, Osterhoff M, Isken F, Pfeiffer AFH, Weickert MO. Increased interleukin-10 but unchanged insulin sensitivity after 4 weeks of (1, 3)(1, 6)-β-glycan consumption in overweight humans. Nutr Res. 2009;29(4):248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cloetens L, Broekaert WF, Delaedt Y, Ollevier F, Courtin CM, Delcour JA, Rutgeerts P, Verbeke K. Tolerance of arabinoxylan-oligosaccharides and their prebiotic activity in healthy subjects: a randomised, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(5):703–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Solà R, Bruckert E, Valls R-M, Narejos S, Luque X, Castro-Cabezas M, Doménech G, Torres F, Heras M, Farrés X et al.. Soluble fibre (Plantago ovata husk) reduces plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, insulin, oxidised LDL and systolic blood pressure in hypercholesterolaemic patients: a randomised trial. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211(2):630–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Russo F, Riezzo G, Chiloiro M, De Michele G, Chimienti G, Marconi E, D'Attoma B, Linsalata M, Clemente C. Metabolic effects of a diet with inulin-enriched pasta in healthy young volunteers. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(7):825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pouteau E, Ferchaud-Roucher V, Zair Y, Paintin M, Enslen M, Auriou N, Macé K, Godin JP, Ballèvre O, Krempf M. Acetogenic fibers reduce fasting glucose turnover but not peripheral insulin resistance in metabolic syndrome patients. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(6):801–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reimer RA, Pelletier X, Carabin IG, Lyon M, Gahler R, Parnell JA, Wood S. Increased plasma PYY levels following supplementation with the functional fiber PolyGlycopleX in healthy adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(10):1186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li S, Guerin-Deremaux L, Pochat M, Wils D, Reifer C, Miller LE. NUTRIOSE dietary fiber supplementation improves insulin resistance and determinants of metabolic syndrome in overweight men: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2010;35(6):773–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ruiz-Roso B, Quintela JC, de la Fuente E, Haya J, Pérez-Olleros L. Insoluble carob fiber rich in polyphenols lowers total and LDL cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2010;65(1):50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pal S, Khossousi A, Binns C, Dhaliwal S, Ellis V. The effect of a fibre supplement compared to a healthy diet on body composition, lipids, glucose, insulin and other metabolic syndrome risk factors in overweight and obese individuals. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(1):90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hashizume C, Kishimoto Y, Kanahori S, Yamamoto T, Okuma K, Yamamoto K. Improvement effect of resistant maltodextrin in humans with metabolic syndrome by continuous administration. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2012;58(6):423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jackson KG, Taylor GRJ, Clohessy AM, Williams CM. The effect of the daily intake of inulin on fasting lipid, insulin and glucose concentrations in middle-aged men and women. Br J Nutr. 1999;82(1):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. de Luis DA, de la Fuente B, Izaola O, Aller R, Gutiérrez S, Morillo M. Double blind randomized clinical trial controlled by placebo with a FOS enriched cookie on satiety and cardiovascular risk factors in obese patients. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28(1):78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Reimer RA, Yamaguchi H, Eller LK, Lyon MR, Gahler RJ, Kacinik V, Juneja P, Wood S. Changes in visceral adiposity and serum cholesterol with a novel viscous polysaccharide in Japanese adults with abdominal obesity. Obesity. 2013;21(9):E379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Childs CE, Röytiö H, Alhoniemi E, Fekete AA, Forssten SD, Hudjec N, Lim YN, Steger CJ, Yaqoob P, Tuohy KM et al.. Xylo-oligosaccharides alone or in synbiotic combination with Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis induce bifidogenesis and modulate markers of immune function in healthy adults: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, factorial cross-over study. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(11):1945–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tripkovic L, Muirhead NC, Hart KH, Frost GS, Lodge JK. The effects of a diet rich in inulin or wheat fibre on markers of cardiovascular disease in overweight male subjects. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28(5):476–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Brahe LK, Le Chatelier E, Prifti E, Pons N, Kennedy S, Blædel T, Håkansson J, Dalsgaard TK, Hansen T, Pedersen O et al.. Dietary modulation of the gut microbiota—a randomised controlled trial in obese postmenopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(3):406–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stenman LK, Lehtinen MJ, Meland N, Christensen JE, Yeung N, Saarinen MT, Courtney M, Burcelin R, Lähdeaho ML, Linros J et al.. Probiotic with or without fiber controls body fat mass, associated with serum zonulin, in overweight and obese adults–randomized controlled trial. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dainty SA, Klingel SL, Pilkey SE, McDonald E, McKeown B, Emes MJ, Duncan AM. Resistant starch bagels reduce fasting and postprandial insulin in adults at risk of type 2 diabetes. J Nutr. 2016;146(11):2252–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Guess ND, Dornhorst A, Oliver N, Frost GS. A randomised crossover trial: the effect of inulin on glucose homeostasis in subtypes of prediabetes. Ann Nutr Metab. 2016;68(1):26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lambert JE, Parnell JA, Tunnicliffe JM, Han J, Sturzenegger T, Reimer RA. Consuming yellow pea fiber reduces voluntary energy intake and body fat in overweight/obese adults in a 12-week randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(1):126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Canfora EE, van der Beek CM, Hermes GDA, Goossens GH, Jocken JWE, Holst JJ, van Eijk HM, Venema K, Smidt H, Zoetendal EG et al.. Supplementation of diet with galacto-oligosaccharides increases bifidobacteria, but not insulin sensitivity, in obese prediabetic individuals. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zunft HJF, Lüder W, Harde A, Haber B, Graubaum HJ, Koebnick C, Grünwald J. Carob pulp preparation rich in insoluble fibre lowers total and LDL cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic patients. Eur J Nutr. 2003;42(5):235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Parnell JA, Reimer RA.. Weight loss during oligofructose supplementation is associated with decreased ghrelin and increased peptide YY in overweight and obese adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(6):1751–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Parnell JA, Klancic T, Reimer RA. Oligofructose decreases serum lipopolysaccharide and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in adults with overweight/obesity. Obesity. 2017;25(3):510–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Alfa MJ, Strang D, Tappia PS, Olson N, DeGagne P, Bray D, Murray B-L, Hiebert B. A randomized placebo controlled clinical trial to determine the impact of digestion resistant starch MSPrebiotic® on glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance in elderly and mid-age adults. Front Med. 2018;4:260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Krumbeck JA, Rasmussen HE, Hutkins RW, Clarke J, Shawron K, Keshavarzian A, Walter J. Probiotic Bifidobacterium strains and galactooligosaccharides improve intestinal barrier function in obese adults but show no synergism when used together as synbiotics. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Peterson CM, Beyl RA, Marlatt KL, Martin CK, Aryana KJ, Marco ML, Martin RJ, Keenan MJ, Ravussin E. Effect of 12 wk of resistant starch supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors in adults with prediabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(3):492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lampe JW, Slavin JL, Baglien KS, Thompson WO, Duane WC, Zavoral JH. Serum lipid and fecal bile acid changes with cereal, vegetable, and sugar-beet fiber feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53(5):1235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]