Abstract

Jakarta, Indonesia's primate city and the world's second largest urban agglomeration, is undergoing a deep transformation. A fresh city profile of Jakarta is long overdue, given that there have been major events and developments since the turn of the millennium (the Asian Financial crisis and decentralisation in Indonesia, among the most important), as well as the fact that the city is a living entity with its own processes to be examined. The inhabitants of the city have also taken centre stage now in these urban processes, including the recent pandemic COVID-19 response. Our paper profiles Jakarta heuristically in two cuts: presenting the city from conventional and academic perspectives of megacities like it, which includes contending with its negative perceptions, and more originally, observing the city from below by paying attention to the viewpoints of citizens and practitioners of the city. In doing so, we draw from history, geography, anthropology, sociology and political science as well as from our experience as researchers who are based in the region and have witnessed the transformation of this megacity from within, with the idea that the portrayal of the city is a project permanently under construction.

Keywords: COVID-19, Everyday transformations, Layered city, Megacity, Permanent temporariness, Smart city

Highlights

-

•

It focuses on Indonesia’s primate city and the world’s second largest urban agglomeration;

-

•

Considering the work of Cybriwsky and Ford (2001) as the most recent one, the paper is meant to be a long overdue fresh city profile of Jakarta;

-

•

In their paper, the authors propose observing Jakarta as a living entity with its own processes to be examined;

-

•

The authors profile the Indonesian capital in two cuts: conventional perspectives of megacities like it, and more originally, observing the city from below through the viewpoints of its citizens and practitioners.

-

•

The profile draws from the social sciences as well as the authors’ experiences as researchers who are based in the region, with the idea that the portrayal of the city is a project permanently under construction.

1. Everyday Jakarta

Present-day Jakarta and its metro area seem a massive and chaotic jumble of concrete, asphalt, vehicles, and people. Each day the streets carry more than 20 million vehicles; every year, approximately 11% more motorcycles, cars, buses, and trucks take to the streets (BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2018).1 On average, motorists spend more than half their daylight hours stuck in traffic, and when they can move, their speed is only about 5 km/h during rush period (Tempo.co, 2015).2

The city (comprising Jakarta and its metro area) spans 4384 km2 and has a population density of around 13,000 people per km2 (Idem). Such a high population density makes land one of the most highly desired commodity in the city, a situation not unlike megacities elsewhere. The continual pressures a rising population put on scarce land result in acute mobility problems and permanent infrastructural deficiencies. Concomitantly, the competition for land in Jakarta gives rise to an endless cycle of conflicts, invasions, evictions, and eternal legal disputes between original owners, developers, and other powerful agents (Herlambang, Leitner, Liong Ju, Sheppard, & Anguelov, 2018).

Every day, city and countryside seem to merge in this spatial conglomerate, in a sort of babel of skin and eye colors, languages, conversations, memories, shouts, watchful eyes, rumors and gossip. Intermingled with sirens, pounding and drilling, singing birds, helicopters' whumping roar, the adhan,3 vehicle horns, squealing cranes, croaking frogs, vendors' harangues, quacking ducks, the roar of engines and the whistling of the wind all become part of the same ubiquitous miasma of vomit, urine, sweat, kretek,4 stagnant water, burning trash, smoked meat, perfume, smog, gorengan,5 kerosene, open sewage, siomay 6 and soto 7 that seem to permanently envelope residents and passers-by alike in Jakarta.

In the preceding paragraphs, we see how time and space materialise in various modalities and intersect in the city of Jakarta, a living, layered landscape of people and objects – a city of cities. Profiling a city with all its complexities and contradictions is never a straightforward or settled endeavour. Nonetheless, we will attempt to do so by heuristically profiling Jakarta in two cuts. First, we approach the city from a conventional perspective, including predictable negative aspects of megacities like Jakarta. Second, in a somewhat more unconventional cut, we propose to profile and understand Jakarta by observing the city from below, by foregrounding the standpoints of citizens and practitioners of the city. This is to illustrate the various ways a city, including Jakarta, could be seen, and how these are being done through understanding the everyday transformations of the city, which evolve across space and time.

Given that the last profile of Jakarta in this journal was published nearly two decades ago (Cybriwsky & Ford, 2001), we believe an updated profile of Jakarta, the capital of the most populous country in Southeast Asia, is long overdue. There have been major developments since the turn of the millennium. The aftermath of the 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis would continue to be felt years later. The same can be said about the new policy of regional autonomy and especially fiscal decentralisation of Indonesia since 1999, making urban development increasingly the remit of local authority. But major events are not the only origins of changes. As researchers who are based in the region and have witnessed the transformation of this megacity from within, our goal is also to reflect on the city as a living entity with its own processes by which means it periodically emerges anew, and to acknowledge how citizens have since become important agents of change in the city. Although the impetus for change and processes are not necessarily unique from other developing cities, the outcomes may well be, such as the aftermath of COVID-19 worldwide. While this profile focuses on Jakarta and its characteristic circumstances, we believe it presents interesting and relevant lessons for perceiving similar cities in the Global South. It posits Jakarta in the fold of a rich literature on these other cities.

2. A conventional view of the city

Jakarta is situated on the northwest coast of Java at the mouth of the Ciliwung, a canalised river over 100 km long that flows from the hinterland of Java, criss-crosses the city, and then empties into the Bay of Jakarta. The Special Capital Region (Daerah Khusus Ibukota - DKI) of Jakarta occupies an area of roughly 664 km2 of land (Table 1 ) and 6977 km2 of sea where the Thousand Islands archipelago (Kepulauan Seribu) is located. The urban sprawl of the city, however, extends well beyond its formal limits (Fig. 1 ). With a population of 10.56 million in 2019, Jakarta is the sixth most populous province in Indonesia, home to 3.94% of its population, and the densest province in Indonesia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of residents, population density and area of the top 6 populous provinces in Indonesia.

| Province | Number of residents in 2019 (% of total population) |

Population density per km2 | Area in km2 (% of Indonesia's area) |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Java | 49.32 million (18.4%) | 1394 | 35,377 (1.85%) |

| East Java | 39.69 million (14.81%) | 831 | 47,803 (2.49%) |

| Central Java | 34.72 million (12.95%) | 1058 | 32,800 (1.71%) |

| North Sumatra | 14.56 million (5.43%) | 200 | 72,981 (3.81%) |

| Banten | 12.92 million (4.82%) | 1338 | 9662 (0.50%) |

| DKI Jakarta | 10.56 million (3.94%) | 15,900 | 664 (0.03%) |

Source: Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia, BPS (2020).

Fig. 1.

Jakarta in Jabodetabek and Java.

Source: Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities (LKYCIC).

As a special capital territory of the Republic of Indonesia, DKI Jakarta assumes the same administrative level of a province (of which there are 34 in Indonesia), with a directly elected governor as its head of city/local government with a 5-year term. The administrative structure of the city consists of the executive branch (i.e. the governor and 4 vice-governors) and the legislative branch (i.e. nominated members of political parties, the armed forces, etc.). Within DKI Jakarta, there are five administrative municipalities – South Jakarta, East Jakarta, Central Jakarta, West Jakarta, North Jakarta (each headed by a mayor appointed by the governor) and one administrative regency, Thousand Islands (headed by an appointed regent). The nature of the DKI Jakarta government is a centralised regional one, with less autonomy for its municipalities than other parts of Indonesia (Cybriwsky & Ford, 2001). These units are further divided into 44 districts (kecamatan) and 267 subdistricts (kelurahan) in total.

Overlapping neighbouring cities, Jakarta and its metro area merge, transforming the Indonesian capital into a megacity, known locally as Jabodetabek (an acronym of Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi) (Fig. 1). With the exception of some hilly areas in southern parts of the city, Jakarta sprawls on a low, flat terrain. Extended parts lie between −2 and 50 m in altitude and, in general, the city's elevation averages just 5 m above sea level. Jakarta is indeed crucially shaped by water. Its shoreline and sea floor are affected by seasonal flooding on an annual basis. The city spreads over a vast area of alluvial lowland resulting from the volcanoes surrounding it, i.e. Salak, Pangrango and Gede. This fertile alluvial plain, crisscrossed by 13 rivers, has historically been swampy, making it highly suitable for rice farming and other agricultural activities. Because of this, and in addition to the river courses, canals and dams water the city's underground.8

Jakarta has a tropical monsoon climate. The rainy season usually starts in November and lasts through June; then the city enters the dry season. Precipitation is more intense in the winter months, between December to March. This close relationship between city and water as well as climate is often obscured by dominant political narratives of flooding being caused by communities living on the riverbanks (Padawangi, 2019). The mitigating solutions mainly involve reclamation projects (Puspa, 2019) and/or moving people away (sometimes through forced evictions) from the riverbanks to widen and deepen the city's rivers (Van Voorst & Padawangi, 2015). These actions may hurt the environment and local livelihoods more than alleviate flooding problems (Chan, 2017; Kusumawijaya, 2016). People are often left to deal with climate change effects on their own as the issue has received little attention from government leaders (Kurniawan, 2018), and, in some cases, to shoulder the blame for them (Van Voorst & Padawangi, 2015).

2.1. Historical background

Jakarta's origins can be traced back centuries, before the city became a colonial settlement, starting from the Neolithic in the Buni area (ca. 400 BCE). Stretching along the north western coast of Java towards the southern hinterlands, various civilisations have been superimposed over each other. One of these, the oldest in the Indonesian archipelago, is Tarumanagara. The remains of this kingdom are represented by the Tugu Inscription found near Tanjung Priok, Jakarta's modern-day port. In the 9th Century, as the Sunda Kingdom emerged as one of Srivijaya's vassals, Sunda Kelapa became known as one of the main port-cities on the coast of northwest Java. The port first became a capital city during this period.

Due to its strategic location, Sunda Kelapa rapidly became a coveted possession of the surrounding Muslim kingdoms of Demak and Cirebon. After Sunda Kelapa fell to Fatahillah, the leader of the Islamic forces, the port's name was changed to Jayakarta, and a short-lived period of glory graced the city (Gultom, 2017). The increasing pressure exerted by the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) would eventually undermine the relationship between the Kingdom of Banten and the English East India Company, leaving the path clear for the Dutch to appropriate and totally control the port. During this period the VOC began constructing the citadel, a spatial reference identified as the starting point of colonial Batavia (Idem).

The historic origin of Batavia has been connected with the arrival of Dutch colonial power and the interaction of Europeans with Chinese and immigrants from other parts of the Indonesian archipelago (Abeyasekere, 1987). However, in spite of some external features, Batavia was far from merely a fortified Dutch city. In fact, some scholars have argued that pre-Dutch cities also had walls and canals and even a similar internal organisation (Miksic, 1990). An example of that is the very notion of kampung. Mistakenly translated as “village” or considered a “Dutch innovation,” kampung was a section within the boundaries of land controlled by a nobleman (Abeyasekere, 1987). By adopting this spatial division in Batavia as well as in other cities, the Dutch were able to separate groups on the basis of ethnic affiliation, religion, occupation or other characteristics. Whatever the origin of kampung, after more than three centuries, the Dutch colonial period left its distinctive mark on the city's landscape (Idem).

The development of Batavia had two epicentres, the first in the north of Jakarta in the area known today as Kota Tua (Old City) (Fig. 2 ),9 close to Sunda Kelapa port, and the second in the southern part of the city, built as a defensive move against recurrent British attacks. This southern area surrounded the Weltevreden, a colonial country estate where the National Monument (Monas), Tanah Abang, Gambir and Lapangan Banteng are now found in Central Jakarta. These landmarks, along with numerous other grand buildings, became symbols of victory and power during the colonial period in the 19th Century. In the 20th Century, after the outbreak of World War II and under the control of the Japanese, the city's colonial glory ended. This interim, characterised by the change of the city's name to Jakarta, marks the beginning of it as the capital of Indonesia, an independent nation.

Fig. 2.

View of the outer side of Kota Tua after the 2014 revitalisation (2019).

Source: Winston Yap, LKYCIC.

The transformation of Jakarta's landscape, particularly between 1950 and 1965, represents the symbolic construction of the new nation by Indonesia's first president, Sukarno (Kusno, 2000). Imagining Jakarta as a showcase or “portal of the country,” Sukarno (1901–1969) envisaged the city as a stage upon which Western (Dutch) and Eastern (Javanese) traditions merge (Idem). Under Sukarno, buildings and monuments in Jakarta mixed two important symbols of power in the Javanese world: monument (tugu) and palace (istana) in one place (Pemberton, 1994). In less than two decades, the capital of a nation self-proclaimed as the world's “beacon of emergent force” was filled with stadia, extensive avenues and boulevards, monuments and wide public spaces.

Such construction, however, would not have been possible without collaboration from regimes on the other side of the Iron Curtain. This collaboration, at times enthusiastic though short-lived, would leave a permanent imprint on the Indonesian capital. Gigantic infrastructure projects such as the Friendship Hospital (Rumah Sakit Persahabatan) (1963) or the Gelora Bung Karno stadium (1962) are just two examples of Russian embedding in Jakarta's landscape. In the context of the 1962 Asian Games, a Soviet-influenced aesthetics emerged virtually everywhere, dominating most of Jakarta's public spaces. Artists, both local and Soviet, were entrusted with producing a prolific iconography in the city (Dovey, 2016). Crowning boulevards and thoroughfares, monuments representing soldiers, peasants and youth were material expressions of progress, friendship and nationhood as well as a strategy meant to educate and imbue all Indonesians with a sense of national pride.

Unlike Sukarno, his successor Suharto (1921–2008) established a goal to differentiate rather than undertake new building projects. In his wish to distance the city from his predecessor, Suharto's new approach to Jakarta was to thwart direct participation by its citizens. This was reflected in the suppression of construction of massive new public spaces. Suharto's approach to public space aimed to portray a new relationship with his citizens, assuming the role of a father who looks for the well-being of his children (Kusno, 2000).

Suharto provided Jakarta with a massive infrastructure, including internal toll roads, flyovers, Indonesia's biggest seaport, Tanjung Priok, and the Soekarno-Hatta international airport along with numerous office buildings, shopping malls, and the so-called superblocks.10 Under Suharto too Jakarta increasingly became an urban environment dominated by the upper classes. Kusno (2000) has argued that gentrification and fear of the underclasses pushed the urban poor off the streets and out of the public areas. This new order built upon technologies of violence and surveillance aimed at disciplining Indonesians while restoring Islamic and Javanese values as binding elements.

Suharto's rule marked by widespread corruption and festering cronyism was finally upended by the global financial crisis in the late 1990s. The ethnic violence during Indonesia's economic crisis, also known as krismon, would be instrumental in bringing down Suharto's New Order and with it went his desire to transform Jakarta into a modern, global city (Firman, 1999; Bunnell & Miller, 2011). The violence before and after krismon led to the exodus of numerous Indonesians of Chinese descent. The departure of this powerful economic minority precipitated a decrease in local investments. Violence and economic collapse were expressed in the city's landscape through stalled and cancelled projects and public works. It also brought about the transformation of entire areas and homes into fortresses.

In the early 2000s, in the aftermath of krismon, to prevent homelessness, unemployment and socio-political unrest, the state allowed urban villages or kampungs and other temporary settlements to grow in “abandoned” or “empty” land, including hidden spaces under toll roads and along riversides and railways in Jakarta (Kusno, A., August 2018, Personal communication). However, as the 2000s progressed, development of Jakarta would gradually resume.

In different parts of the city, particularly in the central area, new office buildings, condominiums, and mega malls along with numerous small cities or enclaves, e.g. SCBD and the further expansion of Jakarta's Golden Triangle (Mega Kuningan), emerged and transformed Jakarta's landscape. Gentrification of extended areas, quasi-privatisation of others, and changes in residential use of land generated tensions between developers and residents, land grabs, and further retreat of the kampung. In spite of these tensions, the city today is still undergoing a deep transformation.

The city's recent transformation took place within the framework of domestic and international events, e.g. river normalisation program, the Southeast Asian Games in 2018, May 2019 election protests and riots (Fig. 3 ). The opening of Jakarta's first MRT line in early 2019 was another factor of change. Other changes, though less visible, are particularly related to co-existence of different uses of the city in close quarters (Fig. 4 ), and the use of digital platforms and other mobile technologies, e.g. technologies people use to navigate the city (Fig. 5 ) or interact with each other in everyday life.

Fig. 3.

Fencing on main roads in Jakarta during May riots (2019).

Source: Rafael Martinez, LKYCIC.

Fig. 4.

Kampung, unmarked graves, and street vendors, all coexisting in proximity, next to a pedestrian bridge.

Source: Rafael Martinez, LKYCIC.

Fig. 5.

Vending machine requiring the use of e-money.

Source: Irna Nurlina Masron, LKYCIC.

2.2. Population

According to official figures, the population of DKI Jakarta is estimated at 10,557,810 people in 2019 (BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2020). That means that in about a decade the city's population has risen by almost 10% since the previous census in 2010. The population distribution in its six administrative divisions (five municipalities and one regency) is as follows: East Jakarta (2.937 million), West Jakarta (2.589 million), South Jakarta (2.264 million), North Jakarta (1.812 million), Central Jakarta (928,110), and Thousand Islands (24,300). Central Jakarta is the most densely populated at 23,875 persons per square kilometre, followed by West Jakarta at 19,592 persons (BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2020). The female-male ratio is almost equal across the divisions. In 2020, the percentage of 15–64 years old, the working age range, in Jakarta's population is about 71%. This is in line with the national situation where the demographic dividend is to be realised on the horizon (expected to peak in 2030) with the working age population constituting 70% of the total population of Indonesia.11

Population growth in Jakarta has been subdued but steady. In 2015, for instance, the population reached 10,180,000, 10,280,000 the next year, 10,370,000 in 2017, 10,467,600 in 2018, and 10,557,810 in 2019 (BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2020). Jakarta and its metro area (Jabodetabek), with more than 30 million people, is the second largest megacity in the world in 2020.12 The suburban areas seem to be where much of the population growth is happening, making up about 84% of the total population growth in the metropolitan area between 2000 and 2010.13

The population census enumerates people in their “usual residence”, which captures where the resident usually lives, or for persons without a fixed residence, it captures where they are found on the night of Census day (BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2018). An identification system in the form of a national identity card (KTP – Kartu Tanda Penduduk) formally registers one as a citizen of Jakarta to be accounted for in official statistics. It is verified and issued by the local authorities, Rukun Tetangga/Rukun Warga (RT/RW), and ties a citizen to the locality (ITU, 2016). This system was upgraded to an electronic one (e-KTP) in 2011, which includes a unique serial number, personal and biometric data and is valid for a lifetime, as opposed to the KTP which has to be renewed every 5 years.

Though it might be difficult to establish an accurate profile of typical Jakartans, it is easy to assert that a number of them are actually migrants. Jakarta is not called a “city of migrants” without cause (Mani, 1993). Various reports and research speak of a “day” and “night” population of Jakarta, primarily because of the huge number of commuters coming into the city from the outskirts during the day. In 2019, a commuter survey by BPS (Table 2 ) showed that there were 3.2 million commuters from the cities of Bogor, Bekasi, Depok, and Tangerang, into the capital, with 63.3% of them using motorcycles and 26.9% public transport (BPS, 2019). This means in DKI Jakarta there are about 14.2 million people during the daytime, when workers stream into the city from the metro area and in the evening, there are about 11 million people.

Table 2.

Jabodetabek population aged 5 and older according to their place of residence and commuter status.

| Residence | Commuter status |

Population 5 years and older |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commuters |

Non-commuters |

|||||

| Total | % | Total | % | Total | % | |

| South Jakarta | 231,383 | 11.5 | 1,785,451 | 88.5 | 2,016,834 | 100 |

| East Jakarta | 341,591 | 13.8 | 2,140,147 | 86.2 | 2,481,738 | 100 |

| Central Jakarta | 100,692 | 13.7 | 632,692 | 86.3 | 733,384 | 100 |

| West Jakarta | 283,069 | 12.7 | 1,937,101 | 87.3 | 2,220,170 | 100 |

| North Jakarta | 137,956 | 9.4 | 1,323,231 | 90.6 | 1,461,187 | 100 |

| Bogor Regency | 408,874 | 8.0 | 4,699,765 | 92.0 | 5,108,639 | 100 |

| Bogor City | 80,325 | 8.9 | 826,503 | 91.1 | 906,828 | 100 |

| Depok | 395,093 | 19.6 | 1,624,093 | 80.4 | 2,019,186 | 100 |

| Tangerang Regency | 236,284 | 7.4 | 2,976,000 | 92.6 | 3,212,284 | 100 |

| Tangerang City | 234,137 | 12.4 | 1,650,181 | 87.6 | 1,884,318 | 100 |

| South Tangerang City | 197,168 | 12.9 | 1,328,812 | 87.1 | 1,525,980 | 100 |

| Bekasi Regency | 240,197 | 7.3 | 3,028,252 | 92.7 | 3,278,449 | 100 |

| Bekasi City | 373,125 | 15.1 | 2,091,049 | 84.9 | 2,464,174 | 100 |

| Jabodetabek | 3,259,894 | 11.1 | 26,053,277 | 88.9 | 29,313,171 | 100 |

Source: BPS (2019)

In addition to this complex picture of Jakarta and the temporal dynamics of its population, internal migration14 has a huge role to play in its demographic realities. 42.5% of the total population of DKI Jakarta in 2010 were lifetime incoming migrants (migran masuk seumur hidup), while 7.3% of its population were recent incoming migrants (migran masuk risen) (BPS, 2012). Lifetime in-migration for DKI Jakarta is the third largest in terms of percentage of its total population in Indonesia. However, recent outmigration from DKI Jakarta surpasses incoming migrants in 2010, therefore the net migration was −2.9% (BPS, 2012). This indicates that while Jakarta is still an attractive place for internal migrants, the number of outmigrants is increasing as they move to neighbouring provinces such as West Java, Banten, and Lampung (Sumatra) (BPS, 2012).

Jakarta has been and will probably continue to be a city of migrants. Yet, judging by some habits of this population, the city might not be the magnet it is alleged to be. In fact, a sizeable proportion of Jakarta's migrant population never actually severed its bonds with their place of origin or made the city their permanent home (BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta, 2018). Families remain in their places of origin, establish their dwellings and create businesses. Hence, not uncommonly, migrants in Jakarta always look to these places as their destination after retiring. This strategy is embraced by numerous, but not all, labourers, providers of services and blue-collar workers. Even though it provides many advantages and benefits for the workers and their families, it takes a heavy toll on the city. This endless cycle of human mobility, perhaps more accurately, the permanent temporariness of migrants in Jakarta, occurs at the expense of government policies crucially dependent on the active engagement of citizens aimed at improving the city of today and planning the city of tomorrow (Deputy Governor DKI, April 2019, Personal interview). The planned relocation of the nation's capital to East Kalimantan might impact on the city in unexpected ways.15

In many cities like Jakarta, the increase in popularity of such citizen engagement approaches and participatory budgeting efforts by the government in the era of decentralisation faces numerous difficulties in terms of fiscal, political and administrative capacities (Bunnell, Miller, Phelps, & Taylor, 2013). However another important issue alluded to earlier which needs more attention is the detachment from the city which urban residents experience because they are more transient and diverse, as compared to rural populations which tend to have stronger patterns of participation (Feruglio & Rifai, 2017). There is also a diversity of profiles among urban residents which participatory budgeting processes often do not take into account, either by design (marginalised groups such as migrants, women, children, people with disabilities) or lack of capacities of local authorities (Feruglio & Rifai, 2017).

Besides internal migration, there is a small but significant population of international migrants, both permanent and temporary, making Jakarta a cosmopolitan city. An important part of this demographic segment is the diplomatic corps and representatives of international organisations including the ASEAN Secretariat, as well as expatriates and refugees.16 At the end of 2018, there were 95,335 foreign workers in Indonesia, an increase of about 11% from 2017, and the majority are professional workers (Kulsum, 2019). These migrants, most covered under the expat umbrella, hail from East Asia (Japan, Korea, China and Taiwan), South Asia (India and Pakistan), and the Middle East (Saudi Arabia, Oman, UAE) among others. The top 5 origin countries are: China, Japan, South Korea, India, and Malaysia (Kulsum, 2019). The arrival of these peoples can be seen, although not exclusively, in the emergence of new businesses and new real estate developments that have mushroomed everywhere in the city. The presence and importance of these populations is also reflected through different forms of space production. These changes in the city's demographics can be seen spatially, as evident in visible enclaves in parts of the city where certain groups live. There are businesses and services catered to the daily life needs of migrants, such as particular religious buildings, supermarkets, restaurants, types of trade, educational institutes, and cultural centres (Ajistyatama, 2014; Hang, 2015).

2.3. Urban problems and planning paradigms

The problems Jakartans experience in daily life are far from new, although they seem to daily renew. Nor are the narratives urging to move the capital far from the current location, and in an environment thoroughly planned from scratch unique to Jakarta.17 One of the most acute problems in Jakarta is pollution and perhaps one of the most obvious forms of pollution is noise. In a city packed with thousands of cars, motorcycles and other types of vehicles, it is no surprise that noise profoundly affects this almost permanently gridlocked capital. It is no wonder that Jakarta was ranked one of the most stressful cities in Asia and the world (Zipjet, 2017). The almost permanent clatter of engines is coupled with daily life noises such as the call to prayer or adhan. Despite appeals from different sectors of society, including Indonesia's former vice president, for the regulation of speakers of mosques, the call to prayer remains a highly sensitive issue in Indonesian society (Tempo.co, 2012).

Another form of pollution permeating almost every aspect of urban life in Jakarta and its metro area is air pollution. In addition to lead, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide and ozone, the particulate matter PM 2.5 is a significant pollutant.18 In Jakarta PM 2.5 averages around 160 which, according to the Air Quality Index (AQI), is considered “unhealthy for everyone” (AQI, 2019). Added to air and noise pollution, water pollution is another important environmental problem in Jakarta.

Although at varying levels and degrees, pollution is also ubiquitous in rivers, canals, and underground water in Jakarta. In the last few years a variety of policies have been formulated to address the problem (Luo et al., 2019). One such policy relates to the eviction of irregular or illegal settlements. Communities along riverbanks or canals have been blamed for littering and using rivers for sewage disposal, not only polluting the water, but making Jakarta more prone to floods (Van Voorst & Padawangi, 2015). Yet water pollution is not a recent problem in Jakarta. In fact, some sources date back its origin from over a century ago through the production of batik.

In the 1900s, the Dutch saw the peripheries of Batavia as ideal for the production of printed batik (batik cap). Areas located in what are now Central and South Jakarta were chosen for their little creeks or streams to drain the excess water from the batik process (Nurdalia, 2006). In mid-1990s, however, the government of Jakarta19 ordered that all batik workshops and factories be relocated from the capital city to the peripheries, particularly to Tangerang, Bekasi or Cikarang. This was meant to curb the pollution of the rivers crisscrossing the city. The regulation, included in the city's first Master Plan, was also intended to push the city's development towards the eastern and western parts of the capital to reduce traffic and demographic density. This ban resulted in further growth of residential areas as former workshops and factories were transformed into private homes. As this regulation implies, one way the government sought to address the city's problems is by redesigning and planning the urban space.

Soon after Jakarta officially became the nation's capital (Undang-Undang No. 4 Tahun 1964), the city government issued its first Master Plan (1965–1985). The Master Plan addressed three main uses of urban land: industrial, unplanned, and public buildings. This led to the creation of avenues and streets, construction of infrastructure, and establishment of more residential areas. Additional residential expansion onto land formerly occupied first by kampung and paddy fields, later by factories and workshops, brought a college-educated and mixed-ethnic urban middle class that thrived in urban Indonesia during the 1980s (Aspinall, 2005; Bresnan, 2005; Taylor, 2012).

Jakarta's next Master Plan (1985–2005) triggered an unprecedented number of changes in residential zones orienting central Jakarta development towards mixed-use. Within years, infrastructural development and a further increase of investments brought a radically different landscape to central Jakarta and Jakarta in general. Hence, during the 1980s new buildings mushroomed almost everywhere on former kampung land. During Suharto's New Order, in effect, Jakarta grew rapidly thanks to an enormous investment in the property sector, focusing particularly on offices, commercial buildings, high-rise residential buildings and hotels (Pravitasari, Saizen, Tsutsumida, Rustiadi, & Pribadi, 2015). In 1988 and 1989 alone, the city's economy grew more than 13.9% (Jakarta Regional Research Council, 2013). Such an increase, thanks largely to the concentration of foreign and domestic investment in the capital, eventually marked the rise of real estate investment and speculative urbanism in Jakarta (Herlambang et al., 2018; Leitner & Sheppard, 2018).

Two decades later, from 2010 onwards, in the framework of the city's 2010–2030 Master Plan, Jakarta has experienced profound changes. Entire areas, particularly in central Jakarta, have once again been divided, into three dominant zones: public, mixed-use and high-rise residential. Tacitly, by not addressing the gaps between zoning regulations and existing conditions in different parts of the city, the new master plan has enabled developers to continue creating more land banks in the permissible densified areas. However, perhaps for the first time ever, the plan has acknowledged the presence and continuity of noncommercial or residential places as religious venues, exempting them from potential eviction, which seems to have expanded almost everywhere in the city.

In addition to spatial planning and infrastructure, public utilities (electricity and gas), water, sanitation, transportation, affordable housing, education are main municipal services which are also to be provided and managed by the provincial government. Though observers have argued that it is lagging in most sectors even though the economy is reportedly growing substantially (Baker, 2012). In this context, there has been a ‘participatory turn’ in this respect as citizen participation in spatial planning and budgeting (musrenbang since 2000, Dana Desa since 2014) has been introduced and organic forms of collaboration in communities such as the urban villages in Jakarta have been encouraged and supported by both non-governmental and governmental efforts (Feruglio & Rifai, 2017).

This is to modify the development since independence which reflects a top-down approach to planning that focuses on serving “the urban elite and link[ing] to global networks of market flows, but have less direct benefits for the majority of the population” (Lo, 2010). While the participatory budgeting has received more attention in terms of making it accessible to the average citizen, this is less of the case in spatial planning. According to the Jakarta Area Spatial Plan (Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Jakarta) 2030, which is a revised plan from the RTRW Jakarta 2010, four strategic issues are highlighted for deeper focus on – transport system and infrastructure, city flood and drainage management system, provision of city utilities (clean water, liquid and solid waste management, telecommunications, energy), and green open spaces (DKI Jakarta, 2011). The 3 main principles undergirding the plan are: managed growth and not development ‘as usual’, the basis of functional planning being the Jabodetabekpunjur Metropolitan, and a shift from ‘stakeholders’ to ‘shareholders’ model (DKI Jakarta, 2011).

There is increasing concern with whether this participatory and community-based planning is being integrated into official mainstream planning (Padawangi, 2019). Some of the major challenges for involvement in participatory budgeting include access to information to identify the needs and priorities of the community, and about the process of participatory budgeting - what happens to the proposals made by citizens, and whether they are being responded to, implemented, or can be monitored (accountability) (Feruglio & Rifai, 2017).

3. The city from below

3.1. Power and morphology in Jakarta

Describing Jakarta's morphology is a complex task as the city is constantly changing and consequently unpredictable. Some scholars have characterised the city's space as layered (Santoso, 2006). The shape Jakarta has adopted derives from a plethora of contextual factors preeminent in different moments throughout its history. The continuous evolution of the city is confirmed not only in the way the master plans have historically imagined the city, but also in the ways proposed solutions to the city's problems have informed Jakartans' identity and their aspirations.

As has happened with other megacities, Jakarta has been compared to different urban models (Goh & Bunnell, 2013), some not necessarily compatible with its permanently shifting morphology subject to dichotomies such as formal and informal, planned and organic. Despite the moderni sation projects the city experienced during the 1960s, Jakarta's space could be the consequence of spontaneous processes. An instance of this is the takeover of kampung land followed by real estate development led mostly by private agents.

In the city's daily life, dichotomies in Jakarta's landscape are expressed in the way planned, sophisticated real estate projects coexist with kampungs or other forms of urban villages. Such dichotomies do not necessarily entail the clash of opposing agendas or ways of imagining the city's space. The kampung takes advantage of its location by providing restaurants, shops, and accommodations among other services, all essential to workers and employees in highly gentrified areas such as the Central Business District (CBD).

Just a few years ago, the final print-out of different projects and modern estate developments was determined by the surrounding kampungs. The print-out resulting from some of the oldest developed areas in Jakarta is the outcome of the Kampung Improvement Program (KIP), initiated more than four decades ago (Irawaty, 2018). Hence, in different parts of the city the resulting design resembled an orthogonal grid. Such design was mostly the outcome of policies which aim to improve the living conditions in kampung areas by transforming the internal road system of kampungs and connecting it to the main roads. Over the years, this spatial configuration was further shaped by a process of densification and layer addition accommodating new generations of inhabitants (Santoso, 2011).

In this layered context, self-help in implementing improvements at the neighbourhood level is a phenomenon which reflects the challenges authorities face in providing public goods, such as sanitation and housing. It has been argued that this practice of spatial production has allowed the cost of providing these public goods to be externalised to communities and residents in terms of resources and time to meet dominant urban imaginaries (UN HRC, 2013). Propagated by authorities, improving living conditions on their own initiative is increasingly being practised (and internalised) by marginalised residents as a way of being and belonging to the city; yet the spatial uncertainties faced by the marginalised who rely on these spaces for residing and working have not been much ameliorated (Padawangi, 2019).

As different cases in the city illustrate, the transformation of extended areas in Jakarta is actually the outcome of a longer period, from colonial times to Indonesia's independence. Rapid modernisation, the country's economic collapse and its recovery brought in different times and circumstances, new uses of land, processes of gentrification and, in general, more layers in the same space (Santoso, 2006). Observing the city as a context resulting from the coexistence of formal and informal is nonetheless complex in Jakarta.

3.2. Jakarta today

Jakarta is nowadays a city engaged in an endless transformation. Not uncommonly, changes in this megacity take place organically, in the context of the informal economy. Daily life practices and different ways to see and produce space continuously shape the city's landscape, leaving their print on it. Other changes, however, are the outcome of top-down policies thoroughly planned and implemented by the state.

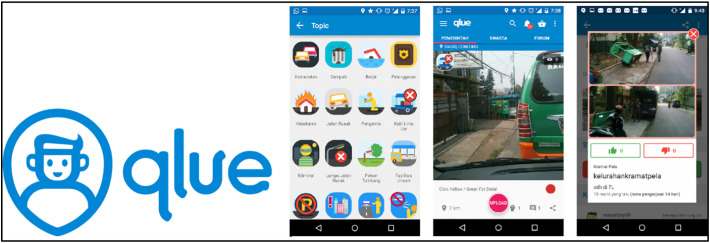

In recent years, particularly in the context of globalisation, the state has dictated a series of policies and regulations meant not only to address Jakarta's regular issues, but to make the city more efficient, less costly and citizen friendly. Since the launch of the Jakarta Smart City program (2014), the city has invested in technology as an effort to improve the services provided to residents (Dewanti, 2014). By means of smartphone applications and installation of CCTV cameras, the city government aims at providing quick response to daily life, including floods, crimes, fires or waste-related issues. Even though Jakarta reports an increase of interaction between the city government and its citizens through applications such as Qlue20 (Fig. 6 ) for residents and CROP for civil servants and officials, the city is still far behind the original goals and expectations. This occurs in spite of the high exposure Indonesians – and particularly Jakartans – have to electronic devices and Internet.21

Fig. 6.

Snapshot of Qlue mobile application.

In recent times, the transformation of the city into a smart one has also been hindered by the overwhelming reality coupled with political aspects, e.g. the fall from grace of Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama, one of its main supporters as the former city governor. Jakarta was recently ranked overall 81st out of 102 cities in the IMD Smart City Index ranking, and 47th out of the Top 50 Smart City governments from over 140 cities globally.22 In response, the city has sought to compensate for this negative outcome through strategies, some based on public relations and further strengthening of Jakarta's branding as a smart city, e.g. Smart City Lounge (http://smartcity.jakarta.go.id/).

As cities are becoming more challenging to manage and inhabit as rapid urbanisation continues, the concept of smart city to address these challenges is being actively propelled and promoted (Cardullo & Kitchin, 2019). However, the transformation of the Jakarta as a smart city begs the question of who the transformation is for and by whom. One of the major critiques is that being a smart city “is too often associated with high technology-powered and large-scale sensing-fed ‘big data’ management”, whereas Perez, Du Chemin, Turpin, and Clarke (2015) argue that the focus should be on nurturing “smart and connected citizens” by drawing upon existing social media and networks, and the potential of individuals. In a bid to increase transparency and inclusiveness of citizen participation processes, technology may be employed, such as the e-musrenbang platforms “through which people can monitor the approval of projects submitted”, though their adoption has been very low due to “low digital literacy and internet use” generally for governance issues. Furthermore, engagement through these platforms “reduces participation to those who have the technical know-how,” thus raises “serious issues of elite capture” (Feruglio & Rifai, 2017).

4. Conclusion

This is the first of a series of papers examining Southeast Asian cities. The goal of this series is not only to present the conventional and academic points of view of a city, but also to embrace learning from people and practitioners in the field and include their experiences and opinions about the city as data.

In this paper, we have provided traditional perspectives from which to regard Jakarta as the first layer, contending with its negative perceptions, and proposing a view of the city from below in the second. By presenting these points of view, we bring forth how practitioners see and live in the city. A major motivation behind this approach is to acknowledge that citizens are transforming Jakarta in different ways and to uncover the mechanisms by which they do so, in order to begin to understand how and how much of citizen participation can and will work in the different spaces of the Indonesian capital. Whatever new ideas, policy, or programs one comes up with to address urban problems and issues, it is imperative to keep in mind the ways in which the city, as a living entity, could and should be seen - the relationship it has with its physical surroundings, the multiplicities of its past, present and future narratives, the diversity of its inhabitants, the seemingly mundane and rhythmic everyday life, and the various nodes of power.

In merging academic theories and methodologies, challenging the empirical stereotypes, and going back to the field to learn from those who practise in the city, we aim to bring this amalgamation to the reader and to demonstrate the potential of these citizen-centric approaches. We are neither making new discoveries nor presenting a definitive view of the city here, for its portrayal is a project permanently under construction. Through this paper we hope to underscore the importance of observing in the field how people live in and shape the city, and of understanding it in an active manner, an understanding which, consequently, is ever evolving and effervescent.

4.1. Epilogue: Jakarta, a living entity

For the more than ten million souls living within its spatial boundaries, Jakarta offers no middle ground: either it is abhorred or adored. Hence its moniker the “Big Durian.” Big Durian, it has been argued by some, is not an equal comparison with New York's Big Apple. Rather, it is a sordid sensorial equivalence the controversial fruit raises among Jakartans. Although intimidating, thorny, repulsive and stinking, like “the king of fruits,” Jakarta could also be exciting, sensual and delectable in strange ways. Jakartans, no matter whether residing temporarily or just passing through seem to be enduringly engaged in a love/hate relationship with the city.

Stereotypes about Jakarta abound. They are produced and reproduced through various mediums, whether in academic pieces, press articles, social media, by government leaders, opposition camps, foreigners, and citizens. A cursory glance of the city in its physical manifestation seems to confirm these often negative views – the traffic gridlock in various parts of the city; the multisensorial pollution which overwhelms newcomers and disenchants old timers; the overpopulation of a sinking city which faces a paradoxical situation with water – suffering from the excess of it during frequent floods, and the lack of it for potable uses; the gentrification of the city which has resulted in further segregation between different groups of people with varied socioeconomic statuses in the city; the permanent transience of its inhabitants and the interminable question who is a Jakartan?

Yet a deeper regard of the city beyond its material expressions reveal the inherent complexities of Jakarta which do not easily yield to a simplistic characterisation of chaos or order – a city historically built against an inconvenient although indelible colonial background; a capital continuously informed by and planned based on ideals, local and imported interpretations of mobility, and competing centres and practices of power; a torn open urban landscape where extended areas have endlessly festered for decades long after violent episodes; a megacity periodically re-engineered, producing the dystopic layers to which it is commonly associated. This is especially critical in the search for resolutions for the both obvious and obscure urban problems and issues. At the time of writing (April 2020), Jakarta is undergoing a partial lockdown in an attempt to contain the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Any city as densely packed and complex as Jakarta would struggle in such an attempt. The authorities, like elsewhere, were caught unawares, even though they had some experience dealing with the Avian Flu in 2009 because the level of preparedness has not been maintained (Nugroho, 2020). The state's incapacity is even more jarring considering how the current pandemic is unlike any the world has seen in recent history.

Tensions showed between the different levels of government on what actions to take, what the priorities should be, who should be calling the shots and providing the resources. Decentralisation in this case has made government response difficult to coordinate, and societal fragmentation is still palpable because of past presidential and coming regional elections (Nugroho, 2020). In the interim, different grassroots organisations have come forth in various ways to compensate for the government's weaknesses in tackling the pandemic and its effects – a situation not unusual to most observers of Indonesia (Preuss, 2020). There was initially an ambivalence regarding restricting movement and banning the annual Ramadan exodus (mudik) because of economic and political rivalry and considerations (Mariani, 2020). President Jokowi needed to keep up his promise of economic growth, and stopping such a massive human movement or a lockdown would impact the economy adversely (AsiaOne, 2020). In addition to the lack of government transparency and public information, societal complexity manifests in how social distancing measures could be confusing and very challenging to enforce. This is especially due to the nature of dense housing (a taken for granted spatial manifestation of social capital) and informal work for many of the city's residents and migrants.

In the current COVID-19 context, a private-sponsored geography of emergency services23 have noticeably appeared in a city where the privatisation of public spaces has inconspicuously been taking place for a while (Fig. 7 ).24 In this seemingly endless COVID-19 interregnum, Jakartans have had to learn to live with an invisible enemy. An enemy whose only existence they know from the mounting cases of fellow citizens, family members and friends infected, and whose disturbing extent they can only infer from the proliferation of unchecked news and rumours, for example, the increasing number of unreported graves in private yards and public parks in populous city neighbourhoods and urban villages. Currently, the numbers of COVID-19 cases and related deaths are tricky to pin down, because of different reporting mechanisms and this is also compounded by multiple factors such as limited testing, testing backlog and inadequate healthcare system (Syakriah, 2020). At the moment, Indonesia is reported to have the highest COVID-19 fatality rate in Asia (Siregar, 2020).

Fig. 7.

Advertising on the Jakarta MRT.

Source: Rafael Martinez, LKYCIC.

One day, Jakartans know, COVID-19 will subside and eventually be gone. But until then, like in the rest of the world, masks, social distancing along with seasonal measures such as the banning of mudik, seem to be the only ways available for Jakartans to palliate the immediate trail of devastation the pandemic leaves on daily basis. It remains to be seen how long other effects of these troubled times, especially those impacting peoples' livelihoods and, of course, their memory of the city, will last.

Author statement

Martinez, Rafael: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing.

Masron, Irna Nurlina: Investigation, Data curation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Harvey Neo for his valuable comments and suggestions for this article.

This work is supported by the Ministry of Education - Singapore [grant number SGPCTRS1802].

Footnotes

Of which 73.92% are motorcycles, passenger cars 19.58%, load vehicles 3.83%, public transportation 1.88% and official vehicles 0.79%. Source: Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) (the Indonesian Central Statistics Agency), 2018.

In 2015, Jakarta's traffic congestion ranked ahead of Istanbul, Mexico City, Surabaya, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Rome, Bangkok, Guadalajara (Mexico), and Buenos Aires. According to Castrol's Magnatec Stop-start Index 2015, motorists in Jakarta made on average 33, 240 start-stops per year. Source: http://www.castrol.com/id_id/indonesia/car-engine-oil/engine-oil-brands/castrol-magnatec-brand/stop-start-index.html.

Islamic call to prayer.

Cigarettes made with a blend of tobacco and cloves.

A fritter, banana, tofu or bakso (meat balls) gorengan is a popular street snack in Indonesian cities.

A strong-smelling steamed fish dumpling with vegetables served with peanut sauce.

A traditional soup of turmeric-colored broth spiced with shallots, garlic, galangal, ginger and coriander, with beef or chicken and vegetables. It is usually served with prawn crackers (krupuk).

It has been estimated that more than half of Jakarta's total population rely on ground wells for water. Source: (ADB, 2016).

See for more on the 2014 Kota Tua Master Plan to conserve and revitalize the historic city centre: Revitalizing Cultural Heritage. A comprehensive urban plan to revitalize Kota Tua in Jakarta, UCLG, 2017. https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/peer_learning_note_22.pdf.

A then brand-new arrangement accommodating offices, apartments, shopping malls and other facilities all in one place.

“Commentary: Are we heading towards demographic bonus or disaster?,” The Jakarta Post, March 5, 2018. https://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2018/03/05/commentary-are-we-heading-toward-demographic-bonus-or-disaster.html.

Demographia World Urban Areas, 16th Annual Edition (April 2020) http://demographia.com/db-worldua.pdf. A megacity is defined as an urban area estimated to have more than 10 million.

Wendell Cox, “The Evolving Urban Form: Jakarta (Jabotabek),” New Geography, May 31, 2011. http://www.newgeography.com/content/002255-the-evolving-urban-form-jakarta-jabotabek. Here suburbs are considered to be within the urban area, but outside the central city of Jakarta.

An “internal migrant” is someone who moves from one place to another to stay, crossing administrative provinces, and is staying in a new dwelling or intends to stay at least 6 months long, with a difference between current and former dwellings is also used as a proxy for migration. Within this, two sets of migrants are identified – a “lifetime migrant” is one whose current dwelling is in a different province from which one was born; a “recent migrant” is one whose dwelling of the last five years is different from the current dwelling. Source: “Migrasi Internal Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010,” BPS, 2012.

“Indonesian president announces site of new capital on Borneo island,” CNA, August 26, 2019. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/indonesia-picks-borneo-island-as-site-of-new-capital-joko-widodo-11842756.

Many of the almost 14,000 refugees and asylum seekers currently in Indonesia are based in Jakarta, with the majority coming from Afghanistan, Somalia and Myanmar, according to the UNHCR in 2019. Source: https://www.unhcr.org/id/en/figures-at-a-glance.

During the late 1950s, Sukarno, Indonesia's first president, envisaged moving the recently independent nation's capital to Palangkaraya (Central Kalimantan) (Labolo, Averus, & Udin, 2018). The idea of moving to Kalimantan, to either Bukit Soeharto, Bukit Nyuling or Palangkaraya came up in 2015, a few months after President Widodo was elected in his first term (The Jakarta Post, 4 May 2019). In 2005, Myanmar replaced its capital Naypyidaw with Yangon, and in 1960, Brazil replaced Rio de Janeiro with Brasilia – both new cities were planned cities. Source: “Why is Indonesia moving its capital city? Everything you need to know,” The Guardian, August 27, 2019.

Less than 2.5 μm in width, these particles can permeate the lungs and cause long-term damage (Xing, Xu, Shi, & Lian, 2016).

Source: KEPUTUSAN MENTERI NEGARA LINGKUNGAN HIDUP NOMOR: KEP-51/MENLH/10/1995. https://lingkunganhidup.jakarta.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Kepmen-LH-No.51-Tahun-1995-Baku-Mutu-Limbah-Cair-Industri.pdf.

“Qlue is a social media app which allows users to report problems directly to the city government and businesses, as well as sharing informations (sic) to the neighbors around them in order to help creating (sic) Smart City. Reports from citizens will be dispatched in real time to the related officials. Each report's status can be monitored using Qlue App and Qlue's Dashboard in mycity.qlue.id.” Retrieved from Google Playstore.

According to the APJII (Association for Internet Service Provider in Indonesia), Internet penetration reached 143 M in 2018. Fifty-eight per cent of internet users are concentrated in Java and the majority (72.41%) are concentrated at the city or regency level.

Sources: IMD Smart City Index, 2019, https://www.imd.org/smart-city-observatory/smart-city-index/; 2018/19 Top 50 Smart City Governments Rankings, Eden Strategy Institute and ONG&ONG (OXD), www.smartcitygovt.com.

Soon after the outbreak of COVID-19, PT Jaya, one of the largest construction companies in Indonesia, sponsored the installation of public sinks on sidewalks to promote hygiene among Jakartans. See “Dorong warga rajin cuci tangan pemprov DKI sediakan wastafel portable di tempat umum (To encourage citizens to wash their hands, the Jakarta government installs portable sinks in public areas),” Terbaiknews, March 23, 2020. https://terbaiknews.net/berita/jakarta/dorong-warga-rajin-cuci-tangan-pemprov-dki-sediakan-wastafel-portabel-di-tempat-umum-3938077.html.

Soon after the opening of Jakarta's first MRT (April 2019), private companies could buy the naming rights (and add their name) to five stations: Dukuh Atas BNI, Setiabudi Astra, Istora Mandiri, Blok M BCA, and Lebak Bulus Grab. After advertising, naming rights constitutes the most important source of revenue for Jakarta's MRT (DetikFinance, 20 November 2019). https://finance.detik.com/infrastruktur/d-4791928/ini-stasiun-mrt-jakarta-yang-dijual-paling-mahal.

References

- Abeyasekere S. Oxford University Press; Singapore: 1987. Jakarta. A history. [Google Scholar]

- Air Quality Index Jakarta air pollution: Real-time air quality index. 2019. https://aqicn.org/city/jakarta/ Retrieved from.

- Ajistyatama W. The Jakarta post. 2014, October 31. Weekly 5: Ethnic enclaves in Jakarta.https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/10/31/weekly-5-ethnic-enclaves-jakarta.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank Indonesia country water assessment. 2016. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/183339/ino-water-assessment.pdf Retrieved from.

- AsiaOne Covid-19: Jokowi draws criticism for statements on lockdown, ‘mudik’. 2020, April. https://www.asiaone.com/asia/covid-19-jokowi-draws-criticism-statements-lockdown-mudik Retrieved from.

- Aspinall E. Stanford University Press; Palo Alto, CA: 2005. Opposing Suharto: Compromise, resistance, and regime change in Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Statistical yearbook of Indonesia. 2020:2020. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2020/04/29/e9011b3155d45d70823c141f/statistik-indonesia-2020.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Baker J.L., editor. Climate change, disaster risk, and the urban poor: Cities building resilience for a changing world. 2012. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/644301468338976600/pdf/683580PUB0EPI0067869B09780821388457.pdf Retrieved from the World Bank website. [Google Scholar]

- BPS Migrasi Internal Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk. 2012, May 23;2010 https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2012/05/23/9cd01b5265c6988245eca87a/migrasi-internal-penduduk-indonesia-hasil-sensus-penduduk-2010 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- BPS Statistik Komuter Jabodetabek: Hasil Survey Komuter Jabodetabek. 2019:2019. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2019/12/04/eab87d14d99459f4016bb057/statistik-komuter-jabodetabek-2019.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta Provinsi DKI Jakarta Dalam Angka. 2018:2018. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/publication/2018/08/16/67d90391b7996f51d1c625c4/provinsi-dki-jakarta-dalam-angka-2018.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- BPS Provinsi DKI Jakarta Provinsi DKI Jakarta Dalam Angka. 2020:2020. https://jakarta.bps.go.id/publication/2020/04/27/20f5a58abcb80a0ad2a88725/provinsi-dki-jakarta-dalam-angka-2020.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Bresnan J. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Ltd.; New York, NY: 2005. Indonesia: The great transition. [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell T., Ann Miller M. Jakarta in post-Suharto Indonesia: decentralisation, neo-liberalism and global city aspiration. Space and Polity. 2011;15(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell T., Miller M.A., Phelps N.A., Taylor J. Urban development in a decentralized Indonesia: Two success stories? Pacific Affairs. 2013;86(4):857–876. [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo P., Kitchin R. Smart urbanism and smart citizenship: The neoliberal logic of ‘citizen-focused’ smart cities in Europe. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. 2019;37(5):813–830. [Google Scholar]

- Chan F. Giant reclamation project in Jakarta hits wall of resistance; The Straits Times: 2017, February. 12.https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/giant-reclamation-project-in-jakarta-hits-wall-of-resistance Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Cybriwsky R., Ford L.R. City profile: Jakarta. Cities. 2001;18(3):199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dewanti W.A. Jakarta launches Smart City program; The Jakarta Post: 2014, December. 16.https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/12/16/jakarta-launches-smart-city-program.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- DKI Jakarta Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah DKI Jakarta 2010–2030. 2011. http://perpustakaan.bappenas.go.id/lontar/opac/themes/bappenas4/templateDetail.jsp?id=166862&lokasi=lokal Retrieved from.

- Dovey K. Bloomsbury Publishing; London: 2016. Urban design thinking: A conceptual toolkit. [Google Scholar]

- Feruglio F., Rifai A. Making All Voices Count Practice Paper. Brighton; IDS: 2017. Participatory budgeting in Indonesia: Past, present and future. [Google Scholar]

- Firman T. From global city ‘to city of crisis’: Jakarta metropolitan region under economic turmoil. Habitat International. 1999;23(4):447–466. [Google Scholar]

- Goh D.P., Bunnell T. Recentering southeast Asian cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2013;37(3):825–833. [Google Scholar]

- Gultom A. Kalapa-Jacatra-Batavia-Jakarta: An old city that never gets old. Journal of Archeology and Fina Arts in Southeast Asia. 2017;2:2–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hang C. Honeycombers. 2015, April 8. Neighbourhoods in Jakarta: Guide to the most popular places to live in the city.https://thehoneycombers.com/jakarta/where-to-live-in-jakarta-neighbourhoods/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Herlambang S., Leitner H., Liong Ju T., Sheppard E., Anguelov D. Jakarta’s great land transformation: Hybrid neoliberalisation and informality. Urban Studies. 2018;56(4):627–648. [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Focus group technical report: Review of national identity programs. 2016. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/focusgroups/dfs/Documents/09_2016/Review%20of%20National%20Identity%20Programs.pdf Retrieved from.

- Irawaty D.T. Jakarta's Kampungs: Their history and contested future. 2018. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55w9b9gg Retrieved from.

- Jakarta Macet Gila, Jarak 5 Km Butuh Waktu 1 Jam Tempo.co. 2015, June 5. https://metro.tempo.co/read/672310/jakarta-macet-gila-jarak-5-km-butuh-waktu-1-jam/full&view=ok Retrieved from.

- Jakarta Regional Research Council Jakarta old city revitalisation. 2013. http://drd-jakarta.org/uploads/files/2.%20Komisi%20B%20-%20KOTA%20TUA1.pdf Retrieved from.

- JK Akan Atur Volume Pengeras Suara Masjid Tempo.co. 2012, July 22. https://nasional.tempo.co/read/418571/jk-akan-atur-volume-pengeras-suara-masjid Retrieved from.

- Kulsum U. Tahun 2018 Tenaga Kerja Asing Naik 10.88 Persen, Kemenaker Nilai Masih Wajar. Tribunbisnis. 2019, January 14. http://www.tribunnews.com/bisnis/2019/01/14/tahun-2018-tenaga-kerja-asing-naik-1088-persen-kemenaker-nilai-masih-wajar Retrieved from.

- Kurniawan T. The future of climate change policy by provincial government in Indonesia: A study on the vision and mission of elected governors in 2017 election. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2018;129:1. [Google Scholar]

- Kusno A. Routledge; London and New York: 2000. Behind the postcolonial: Architecture, urbanism and political cultures in Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Kusumawijaya M. Jakarta at 30 million: my city is choking and sinking – It needs a new Plan B. 2016, November 21. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/nov/21/jakarta-indonesia-30-million-sinking-future Retrieved from.

- Labolo M., Averus A., Udin M.M. Determinant factor of central government relocation in Palangkaraya, Central Kalimantan Province. International Journal of Business and Management. 2018;2(3):52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner H., Sheppard E. From Kampungs to condos? Contested accumulations through displacement in Jakarta. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 2018;50(2):437–456. [Google Scholar]

- Lo R.H. The city as a mirror: Transport, land use and social change in Jakarta. Urban Studies. 2010;47(3):529–555. [Google Scholar]

- Luo P., Kang S., Apip, Zhou M., Lyu J., Aisyah S.…Nover D. Water quality trend assessment in Jakarta: A rapidly growing Asian megacity. PLoS One. 2019;14(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6623954/ Retrieved from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani A. Indians in Jakarta. In: Sandhu K.S., Mani A., editors. Indian communities in Southeast Asia. Singapore; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mariani E. Jokowi finally takes Covid-19 seriously, but more must be done: Jakarta Post columnist. The Straits Times. 2020, March. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/jokowi-finally-takes-covid-19-seriously-but-more-must-be-done-jakarta-post-columnist Retrieved from.

- Miksic J.N. University of Hawaii Press; Honolulu: 1990. Old Javanese gold. [Google Scholar]

- Nugroho Y. Indonesia's Covid-19 response. Talking Indonesia. 2020, April. https://soundcloud.com/talking-indonesia/dr-yanuar-nugroho-indonesias-covid-19-response Retrieved from.

- Nurdalia I. Universitas Diponegoro; Semarang, Indonesia: 2006. Kajian dan analisis peluang penerapan produksi bersih pada usaha kecil batik cap (Studi kasus pada tiga usaha industri kecil batik cap di Pekalongan) (Unpublished Master’s thesis). [Google Scholar]

- Padawangi R. Forced eviction, spatial (un)certainties and the making of exemplary centres in Indonesia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. 2019;60(1):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton J. Recollections from “Beautiful Indonesia” (somewhere beyond the postmodern) Public Culture. 1994;6(2):241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Perez P., Du Chemin T.H., Turpin E., Clarke R. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Self-Adaptive and Self-Organizing Systems Workshops. 2015. Citizen-driven flood mapping in Jakarta: A self-organising socio-technical system. [Google Scholar]

- Pravitasari A.E., Saizen I., Tsutsumida N., Rustiadi E., Pribadi D.O. 2015. Local spatially dependent driving forces of urban expansion in an emerging Asian megacity: The case of Greater Jakarta (Jabodetabek) Journal of Sustainable Development 8, 1, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Preuss S. Indonesia and COVID-19: What the world is missing. The Diplomat. 2020, April. https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/indonesia-and-covid-19-what-the-world-is-missing/ Retrieved from.

- Puspa S. Staying in Jakarta: Will a great sea wall protect Indonesia's capital from coastal flooding? 2019, June 29. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/indonesia-jakarta-flooding-great-sea-wall-11662564 Retrieved from.

- Santoso J. Kepustakaan, Populer Gramedia; Jakarta: 2006. Menyiasati kota tanpa warga. [Google Scholar]

- Santoso J. Graduate Program of Urban Planning Centropolis, Tarumanegara University; Jakarta: 2011. The fifth layer of Jakarta. [Google Scholar]

- Siregar K. Why Indonesia has the highest COVID-19 fatality rate in Asia. 2020, April. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asia/covid-19-fatality-rate-highest-asia-indonesia-12669500 Retrieved from.

- Syakriah A. An examination of Indonesia's death toll: Could it be higher? 2020, April. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/04/28/an-examination-of-indonesias-death-toll-could-it-be-higher.html Retrieved from.

- Taylor J.G. Routledge; London: 2012. Global Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- UN Human Rights Council Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context on her mission to Indonesia. 2013. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session25/Documents/A-HRC-25-54-Add1_en.doc Retrieved from.

- Van Voorst R., Padawangi R. Floods and forced evictions in Jakarta. 2015. August 21.https://www.newmandala.org/floods-and-forced-evictions-in-jakarta/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y.F., Xu Y.H., Shi M.H., Lian Y.X. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2016;8(1):E69–E74. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipjet The 2017 global least & most stressful cities ranking. 2017. https://www.zipjet.co.uk/2017-stressful-citiesranking Retrieved from.