Abstract

Background:

Myocardial infarction (MI) complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS) is associated with high mortality. Early coronary revascularization improves survival, but the optimal mode of revascularization remains uncertain. We sought to characterize practice patterns and outcomes of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with MI complicated by CS.

Methods:

Patients hospitalized for MI with CS between 2002 and 2014 were identified from the United States National Inpatient Sample. Trends in management were evaluated over time. Propensity score matching was performed to identify cohorts with similar baseline characteristics and MI presentations who underwent PCI and CABG. The primary outcome was in-hospital all-cause mortality.

Results:

A total of 386,811 hospitalizations for MI with CS were identified; 67% were STEMI. Overall, 62.4% of patients underwent revascularization, with PCI in 44.9%, CABG in 14.1%, and a hybrid approach in 3.4%. Coronary revascularization for MI and CS increased over time, from 51.5% in 2002 to 67.4% in 2014 (p-for-trend<0.001). Patients who underwent CABG were more likely to have diabetes mellitus (35.5% vs. 29.2%, p<0.001) and less likely to present with STEMI (48.7% vs. 80.9%, p<0.001) than those who underwent PCI. CABG (without PCI) was associated with lower mortality than PCI (without CABG) overall (18.9% vs. 29.0%, p<0.001) and in a propensity-matched subgroup of 19,882 patients (19.0% vs. 27.0%, p<0.001).

Conclusions:

CABG was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than PCI among patients with MI complicated by CS. Due to the likelihood of residual confounding, a randomized trial of PCI versus CABG in patients with MI, CS, and multi-vessel coronary disease is warranted.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, coronary artery bypass grafting, myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, mortality

Graphical Abstract

Background:

Myocardial infarction (MI) complicated by cardiogenic shock is associated with high early mortality.1 Although early coronary revascularization improves survival in cardiogenic shock, the 30-day mortality rate of 35–45% has persisted for decades despite advances in anti-thrombotic pharmacology, use of left ventricular support, and contemporary PCI techniques.1–7 Multi-vessel PCI in patients with MI and cardiogenic shock results in higher mortality compared with PCI of the culprit lesion only.4,8 Thus, the optimal mode of revascularization remains uncertain. Non-randomized studies, including data from the original SHOCK trial, suggest a potential benefit from complete revascularization and cardioprotective measures employed with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in patients with cardiogenic shock.9,10 However, the optimal approach to coronary revascularization for patients with MI, multi-vessel coronary artery disease, and cardiogenic shock is still unknown. We sought to characterize practice patterns and compare outcomes of CABG and PCI in patients with MI complicated by cardiogenic shock in a large national database of United States hospital admissions.

Methods:

Study Population

Adults age ≥18 years who were hospitalized for acute MI with cardiogenic shock between January 1st 2002 and December 31st 2014 were identified from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). The NIS is a publicly available database from the United States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) that reports all discharges from a 20% sample of participating hospitals through 2011, and a 20% sample of discharges from all hospitals participating in HCUP thereafter. Individual hospitalizations are de-identified and assigned a primary diagnosis and up to 29 secondary diagnosis codes. Patients assigned a primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code for acute myocardial infarction, including acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (410.01 to 410.61, 410.81, and 410.91) or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (410.71), and with had an ICD-9 diagnosis code for cardiogenic shock (785.51) in any position, were included in the analysis.11 Coronary anatomy data were not available in the NIS and therefore patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD) could not be identified. Demographics and clinical comorbidities were defined by relevant ICD-9 diagnosis codes and AHRQ comorbidity measures.

Management and Outcomes

Coronary revascularization was defined by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), as reported by ICD-9 and CCS procedure codes during the index hospitalization. The timing of coronary revascularization relative to the onset of cardiogenic shock was not recorded in the NIS. Patients who did not undergo coronary revascularization for MI with cardiogenic shock during the index hospitalization were considered to have been managed medically. The primary outcome of the study was all-cause, in-hospital mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics, clinical comorbidities, and in-hospital outcomes were evaluated by coronary revascularization strategy. Categorical variables reported as percentages and were compared by χ2 tests. Continuous variables were reported as means and standard error of measurement (SEM) and were compared using linear regression. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate odds of mortality associated with coronary revascularization adjusted for patient demographics and clinical covariates. Models included demographics (age, sex, race), cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities including tobacco use, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, prior PCI, prior CABG, congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, anemia, malignancy, and all other AHRQ comorbidity measures. Models also included characteristics of the MI presentation, such as presentation with STEMI, cardiac arrest, need for mechanical circulatory support, emergency room admission versus inter-facility transfer, presentation during the weekend, year of presentation, and hospital characteristics, including hospital size, region, teaching vs. nonteaching hospital status, and the primary insurance payer for the admission.

To evaluate the association between coronary revascularization strategies and mortality, propensity scores were generated to identify cohorts of patients with MI, cardiogenic shock, and similar baseline characteristics who underwent PCI and CABG. Covariates in the logistic regression model included patient demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, relevant clinical comorbidities, characteristics of the MI presentation, and hospital characteristics as described above. Propensity score matching was performed using a 1:1 matching protocol (without replacement) with a caliper width of 0.05 of the SD of the logit of the propensity score. Absolute standardized differences (ASD) were estimated before and after matching to assess pre-match and post-match imbalance. Absolute standardized differences ≤10% indicate minimal imbalances in baseline characteristics between the two groups. To account for residual imbalance between the two groups after propensity score matching, multivariable logistic regression was performed on the matched sample to estimate the adjusted odds of mortality associated with each coronary revascularization strategy. In order to confirm the consistency of these findings, we performed subgroup analyses of patients who presented with STEMI and NSTEMI. To address immortal time bias that could favor survival in patients who were referred for CABG, we performed propensity score matching in a sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who died within the first 24 hours of hospital admission for MI with cardiogenic shock. We also performed propensity score matching by revascularization strategy in a sensitivity analysis of patients who underwent coronary revascularization on the day of hospital admission. To confirm the consistency of these findings in the contemporary time period with second-generation drug eluting stents and revascularization with arterial bypass grafts, matched cohorts of patients undergoing PCI and CABG from 2010–2014 were also compared.

To determine national incidence estimates and trends over time, all analyses in the overall population were performed using complex survey analysis methods that incorporate sampling weights, clustering, and strata. Unweighted analyses were performed in the propensity-matched subgroups. Trends over time were evaluated using the Mantel-Haenszel test for trend. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical tests are two-sided and P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The NIS is a de-identified dataset that is publicly available, and the study was exempt from local institutional board review. The work was supported in part by an NYU CTSA grant, UL1 TR001445 and KL2 TR001446, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper, and its final contents.

Results:

Patients

A total of 386,811 hospitalizations for acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock were identified from 2002 to 2014. Of these cases, 66.5% (n=257,286) of patients presented with STEMI and 33.5% (n=129,525) presented with NSTEMI. Cardiac arrest was reported in 18.7% of cases (n=72,369), with a greater frequency among patients who presented with STEMI compared with NSTEMI (20.7% vs. 14.8%, p<0.001).

Management

Overall, 62.4% of patients underwent coronary revascularization for MI and cardiogenic shock. Patients with MI and cardiogenic shock who underwent coronary revascularization were younger and more likely to be men compared to those who were managed without coronary revascularization. Full clinical characteristics of patients by coronary revascularization strategy are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Among patients with MI and cardiogenic shock, PCI (without CABG) was performed in 44.9% of cases (n=173,553), CABG (without PCI) was performed in 14.1% of cases (n=54,564), and a hybrid approach to revascularization (with PCI and CABG) was employed in 3.4% of cases (n=13,222). Patients who underwent CABG without PCI were more likely to be men and have diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, and renal disease than those who underwent PCI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical comorbidities of patients with MI and cardiogenic shock

| All MI with Cardiogenic Shock (n=386,811) | Coronary Revascularization (n=241,339) | Medical Management (n=145,472) | p-value | PCI Only (n=173,553) | CABG Only (n=54,564) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, years (S.E.) | 68.93 (0.080) | 66.19 (0.083) | 73.48 (0.108) | <0.001 | 66.3 (0.091) | 66.50 (0.137) | 0.168 |

| Female Sex | 149508 (38.7%) | 84291 (34.9%) | 65216 (44.8%) | <0.001 | 62908 (36.2%) | 17298 (31.7%) | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| White Non-Hispanic | 243528 (63%) | 152309 (63.1%) | 91219 (62.7%) | 110501 (63.7%) | 33430 (61.3%) | ||

| Black Non-Hispanic | 23150 (6%) | 13284 (5.5%) | 9866 (6.8%) | 9497 (5.5%) | 3162 (5.8%) | ||

| Hispanic | 25357 (6.6%) | 15853 (6.6%) | 9504 (6.5%) | 10968 (6.3%) | 4033 (7.4%) | ||

| Other | 24635 (6.4%) | 16016 (6.6%) | 8619 (5.9%) | 11001 (6.3%) | 4131 (7.6%) | ||

| Unknown | 70140 (18.1%) | 43876 (18.2%) | 26263 (18.1%) | 31585 (18.2%) | 9808 (18%) | ||

| Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Comorbidities | |||||||

| Tobacco Use (Current or Former) | 94451 (24.4%) | 69303 (28.7%) | 25149 (17.3%) | <0.001 | 51620 (29.7%) | 13866 (25.4%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 194482 (50.8%) | 122289 (51.1%) | 72193 (50.3%) | 0.071 | 87214 (50.6%) | 28575 (53%) | 0.002 |

| Dyslipidemia | 132875 (34.4%) | 92713 (38.4%) | 40161 (27.6%) | <0.001 | 67677 (39%) | 20225 (37.1%) | 0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus, any | 123484 (31.9%) | 74049 (30.7%) | 49435 (34.0%) | <0.001 | 50657 (29.2%) | 19379 (35.5%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus with chronic complications | 23375 (6.1%) | 13331 (5.6%) | 10044 (7%) | <0.001 | 8354 (4.9%) | 4345 (8.1%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 100109 (26.2%) | 60718 (25.4%) | 39391 (27.4%) | <0.001 | 42303 (24.6%) | 15034 (27.9%) | <0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 16328 (4.2%) | 5166 (2.1%) | 11162 (7.7%) | <0.001 | 4634 (2.7%) | 448 (0.8%) | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 27186 (7%) | 17111 (7.1%) | 10075 (6.9%) | 0.428 | 13343 (7.7%) | 2974 (5.5%) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 13587 (3.5%) | 9538 (4%) | 4049 (2.8%) | <0.001 | 5124 (3%) | 3739 (6.9%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 43779 (11.4%) | 25669 (10.7%) | 18111 (12.6%) | <0.001 | 17048 (9.9%) | 7436 (13.8%) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 1118 (0.3%) | 792 (0.3%) | 326 (0.2%) | 0.009 | 337 (0.2%) | 386 (0.7%) | <0.001 |

| Valvular Heart Disease | 3457 (0.9%) | 2408 (1%) | 1049 (0.7%) | <0.001 | 693 (0.4%) | 1489 (2.8%) | <0.001 |

| Other Comorbidities | |||||||

| Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome | 573 (0.1%) | 371 (0.2%) | 203 (0.1%) | 0.632 | 313 (0.2%) | 48 (0.1%) | 0.028 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 13256 (3.5%) | 8925 (3.7%) | 4331 (3%) | <0.001 | 6391 (3.7%) | 2036 (3.8%) | 0.759 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 5811 (1.5%) | 3736 (1.6%) | 2074 (1.4%) | 0.217 | 2643 (1.5%) | 861 (1.6%) | 0.701 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 84466 (22.1%) | 51557 (21.5%) | 32908 (22.9%) | <0.001 | 34787 (20.2%) | 13750 (25.5%) | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 50664 (13.2%) | 36198 (15.1%) | 14465 (10.1%) | <0.001 | 18028 (10.5%) | 14813 (27.5%) | <0.001 |

| Deficiency Anemias | 65943 (17.2%) | 39863 (16.7%) | 26080 (18.2%) | <0.001 | 28543 (16.6%) | 9090 (16.9%) | 0.585 |

| Depression | 16226 (4.2%) | 9821 (4.1%) | 6405 (4.5%) | 0.022 | 7270 (4.2%) | 2076 (3.9%) | 0.104 |

| Drug abuse | 5951 (1.6%) | 4165 (1.7%) | 1786 (1.2%) | <0.001 | 3103 (1.8%) | 828 (1.5%) | 0.071 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 158052 (41.3%) | 94809 (39.6%) | 63242 (44.1%) | <0.001 | 66129 (38.4%) | 23356 (43.3%) | <0.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 28923 (7.6%) | 16156 (6.8%) | 12767 (8.9%) | <0.001 | 12059 (7%) | 3440 (6.4%) | 0.028 |

| Liver disease | 5570 (1.5%) | 2876 (1.2%) | 2694 (1.9%) | <0.001 | 2059 (1.2%) | 656 (1.2%) | 0.856 |

| Lymphoma | 2037 (0.5%) | 1088 (0.5%) | 949 (0.7%) | <0.001 | 798 (0.5%) | 256 (0.5%) | 0.873 |

| Metastatic cancer | 3429 (0.9%) | 1293 (0.5%) | 2135 (1.5%) | <0.001 | 1178 (0.7%) | 111 (0.2%) | <0.001 |

| Neurological disorders | 27164 (7.1%) | 13270 (5.5%) | 13893 (9.7%) | <0.001 | 10373 (6%) | 2322 (4.3%) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 33895 (8.9%) | 24583 (10.3%) | 9312 (6.5%) | <0.001 | 16243 (9.4%) | 6782 (12.6%) | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 7706 (2%) | 4025 (1.7%) | 3681 (2.6%) | <0.001 | 2564 (1.5%) | 1218 (2.3%) | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 272 (0.1%) | 132 (0.1%) | 140 (0.1%) | 0.032 | 95 (0.1%) | 37 (0.1%) | 0.568 |

| Psychoses | 7231 (1.9%) | 4491 (1.9%) | 2740 (1.9%) | 0.756 | 3306 (1.9%) | 966 (1.8%) | 0.417 |

| Renal failure | 74069 (19.3%) | 37303 (15.6%) | 36765 (25.6%) | <0.001 | 25758 (15%) | 10109 (18.8%) | <0.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases | 6878 (1.8%) | 4171 (1.7%) | 2706 (1.9%) | 0.16 | 3223 (1.9%) | 751 (1.4%) | 0.001 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 6320 (1.7%) | 3043 (1.3%) | 3277 (2.3%) | <0.001 | 2423 (1.4%) | 511 (0.9%) | <0.001 |

| Weight Loss | 22382 (5.8%) | 14704 (6.1%) | 7678 (5.3%) | <0.001 | 7974 (4.6%) | 5647 (10.5%) | <0.001 |

Table 2.

Presentation and characteristics of hospitalizations for MI and cardiogenic shock

| All MI with Cardiogenic Shock (n=386,811) | Coronary Revascularization (n=241,339) | Medical Management (n=145,472) | p-value | PCI Only (n=173,553) | CABG Only (n=54,564) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation Characteristics | |||||||

| STEMI Presentation | 257286 (66.5%) | 177682 (73.6%) | 79604 (54.7%) | <0.001 | 140481 (80.9%) | 26546 (48.7%) | <0.001 |

| NSTEMI Presentation | 129525 (33.5%) | 63657 (26.4%) | 65868 (45.3%) | <0.001 | 33072 (19.1%) | 28018 (51.3%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 72369 (18.7%) | 45935 (19%) | 26434 (18.2%) | 0.005 | 37783 (21.8%) | 6019 (11.0%) | <0.001 |

| Transferred in from another facility | 57629 (14.9%) | 38893 (16.1%) | 18736 (12.9%) | <0.001 | 24802 (14.3%) | 12311 (22.6%) | <0.001 |

| Weekend Presentation | 104211 (26.9%) | 64708 (26.8%) | 39503 (27.2%) | 0.298 | 48125 (27.7%) | 13008 (23.8%) | <0.001 |

| Hospital Characteristics | |||||||

| Hospital Size * | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Small | 30250 (7.8%) | 15598 (6.5%) | 14652 (10.1%) | 11753 (6.8%) | 3094 (5.7%) | ||

| Medium | 85690 (22.2%) | 50087 (20.8%) | 35603 (24.5%) | 37296 (21.6%) | 10275 (18.9%) | ||

| Large | 269695 (69.9%) | 174900 (72.7%) | 94795 (65.4%) | 123899 (71.6%) | 41087 (75.5%) | ||

| Hospital Location * | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Rural | 27082 (7%) | 11605 (4.8%) | 15477 (10.7%) | 9600 (5.6%) | 1495 (2.7%) | ||

| Urban Non-teaching | 155571 (40.3%) | 94777 (39.4%) | 60794 (41.9%) | 70554 (40.8%) | 18747 (34.4%) | ||

| Urban Teaching | 202982 (52.6%) | 134203 (55.8%) | 68779 (47.4%) | 92793 (53.7%) | 34214 (62.8%) | ||

| Hospital Region | <0.001 | 0.002 | |||||

| Northeast | 70579 (18.2%) | 37986 (15.7%) | 32593 (22.4%) | 26876 (15.5%) | 9412 (17.3%) | ||

| Midwest or North Central | 89101 (23%) | 58560 (24.3%) | 30541 (21%) | 43522 (25.1%) | 11659 (21.4%) | ||

| South | 147486 (38.1%) | 93533 (38.8%) | 53953 (37.1%) | 66311 (38.2%) | 21817 (40%) | ||

| West | 79645 (20.6%) | 51260 (21.2%) | 28385 (19.5%) | 36845 (21.2%) | 11676 (21.4%) | ||

| Payer Type | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Medicare | 234749 (60.8%) | 128843 (53.5%) | 105905 (72.9%) | 93014 (53.7%) | 30139 (55.3%) | ||

| Medicaid | 25428 (6.6%) | 17429 (7.2%) | 7999 (5.5%) | 12311 (7.1%) | 4098 (7.5%) | ||

| Private insurance | 93156 (24.1%) | 70463 (29.2%) | 22693 (15.6%) | 50588 (29.2%) | 14962 (27.5%) | ||

| Self-Pay | 20932 (5.4%) | 15468 (6.4%) | 5464 (3.8%) | 11374 (6.6%) | 3126 (5.7%) | ||

| No Charge | 1716 (0.4%) | 1329 (0.6%) | 386 (0.3%) | 853 (0.5%) | 389 (0.7%) | ||

| Other | 10254 (2.7%) | 7440 (3.1%) | 2815 (1.9%) | 5140 (3%) | 1782 (3.3%) | ||

Data available for 385,635 hospitalizations

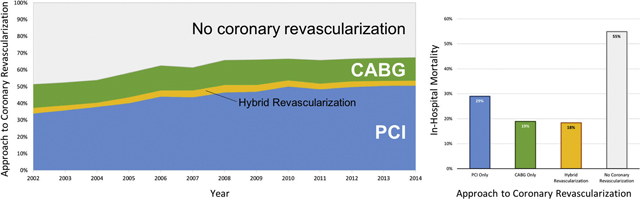

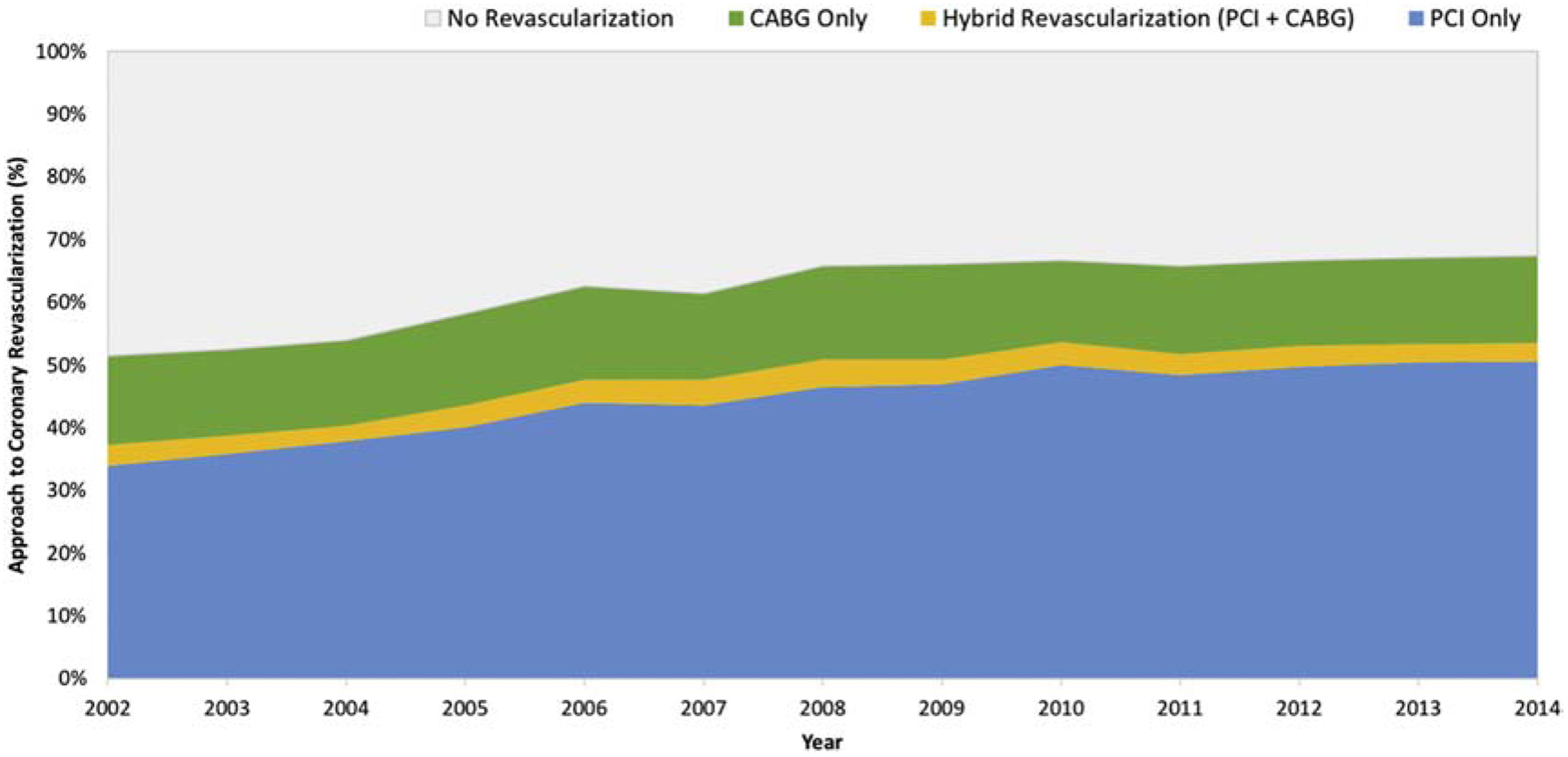

Over the 13-year study period, the frequency of coronary revascularization for MI and cardiogenic shock increased from 51.5% in 2002 to 67.4% in 2014 (p-for-trend<0.001). The frequency of PCI for MI with cardiogenic shock increased from 34.0% in 2002 to 50.7% in 2014 (p-for-trend<0.001), while rates of CABG declined slightly from 14.2% in 2002 to 13.9% in 2014 (p-for-trend 0.018). Trends in the approach to coronary revascularization for patients with MI and cardiogenic shock are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trends in the approach to coronary revascularization among patients with MI and cardiogenic shock

In the subgroup of patients who presented with STEMI and cardiogenic shock, coronary revascularization was performed in 69.1% of cases, with an increase in the proportion of patients undergoing coronary revascularization from 55.6% in 2002 to 77.1% in 2014 (p-for-trend<0.001). Coronary revascularization was achieved with PCI alone in 54.6% of STEMI cases, CABG without PCI in 10.3%, and a hybrid approach to coronary revascularization (with PCI and CABG) in 4.1%. CABG without PCI was performed less frequently in patients with cardiogenic shock and STEMI compared with NSTEMI (10.3% versus 21.6%, p<0.001).

Among all patients with MI (NSTEMI or STEMI) and cardiogenic shock who underwent coronary revascularization with PCI (without CABG), drug eluting stents were used in 46.0% of cases, bare metal stents were used in 41.0%, and balloon angioplasty without stent placement was performed in 13.0%. PCI was performed on the day of hospital admission in 68.5% of cases, on hospital day 1 in 7.1% of cases, on hospital day 2 in 2.2% cases, and beyond hospital day 2 in 5.2% of cases. The timing of PCI was not recorded in 16.9% of cases. Among patients who underwent CABG, bypass grafts to multiple coronary vessels were placed in 84.6% of cases (Supplemental Table 1). Single vessel CABG was only reported in 12.9% of cases. CABG was performed on the day of hospital admission in 24.9% of cases, on hospital day 1 in 17.1% of cases, on hospital day 2 in 10.7% of cases, and beyond hospital day 2 in 35.0% of cases. The timing of CABG was not recorded in 12.3% of cases.

Placement of a mechanical circulatory support (MCS) device was common during hospitalization for MI and cardiogenic shock in patients who underwent coronary revascularization. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsion was initiated in 60.1% of such hospitalizations, with a greater frequency in patients undergoing CABG alone compared with PCI (64% vs. 57.4%, p<0.001). Advanced MCS with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device (LVAD) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was reported in 2.7% of patients undergoing coronary revascularization during the study period, with a greater frequency of use among patients who underwent PCI compared with CABG (2.9% versus 2.0%, p<0.001) (Supplemental Table 2). Trends in MCS use during hospital admission for MI and cardiogenic shock are shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Outcomes

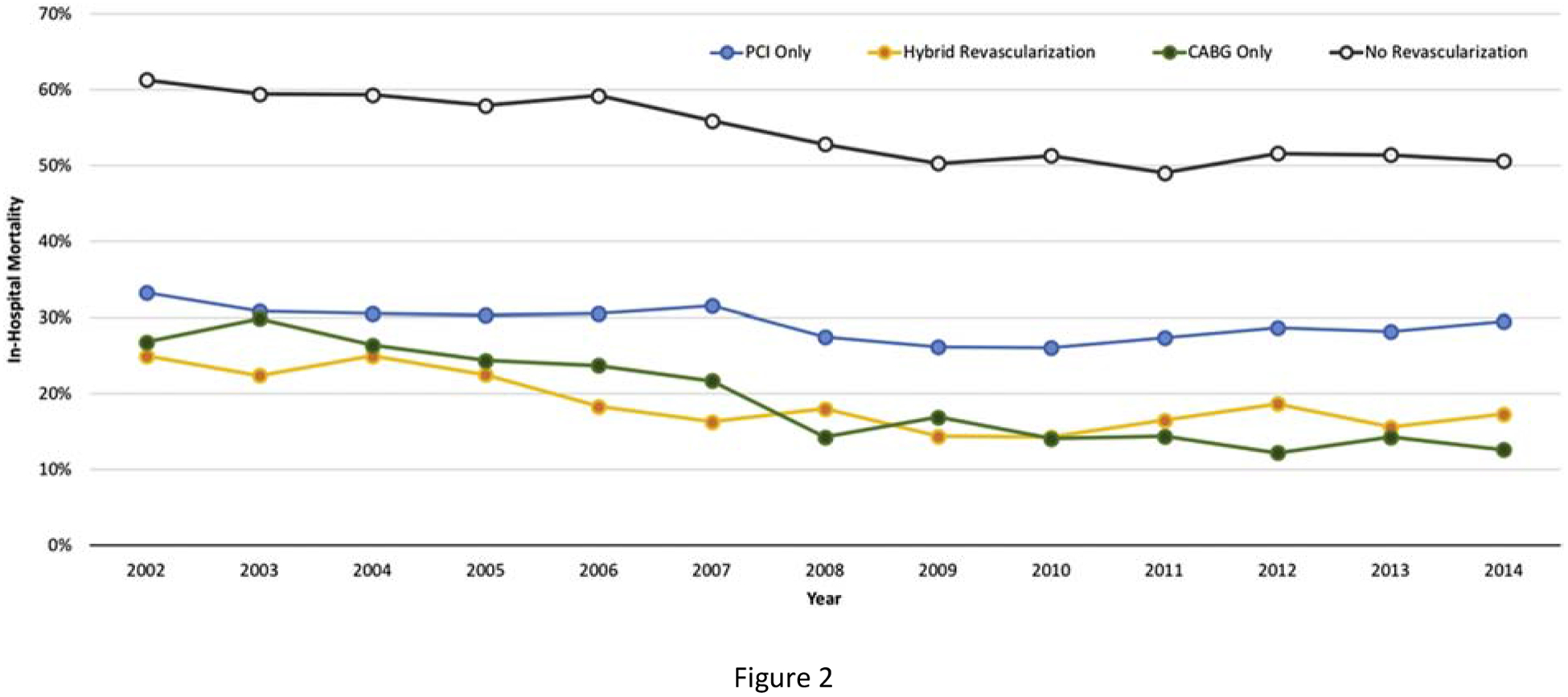

All-cause mortality during hospitalization for MI and cardiogenic shock was 36.9% overall, with 37.9% mortality among patients presenting with STEMI and 35.0% in those with NSTEMI. Patients who underwent coronary revascularization had lower mortality than those who did not undergo revascularization (26.1% vs. 54.9%, p<0.001) (Table 3). Among patients who underwent coronary revascularization, those who underwent CABG (without PCI) had lower mortality than those who underwent PCI alone (18.9% vs. 29.0%, p<0.001; Table 3, Supplemental Figure 1). Trends in in-hospital mortality over time by coronary revascularization strategy are shown in Figure 2.

Table 3.

In-hospital outcomes of MI and cardiogenic shock, by approach to coronary revascularization

| All MI with Cardiogenic Shock (n=386,811) | Coronary Revascularization (n=241,339) | Medical Management (n=145,472) | p-value | PCI Only (n=173,553) | CABG Only (n=54,564) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of Stay, days (S.E.) | 9.34 (0.083) | 10.78 (0.091) | 6.95 (0.105) | <0.001 | 8.58 (0.068) | 16.60 (0.186) | <0.001 |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 142845 (36.9%) | 63030 (26.1%) | 79815 (54.9%) | <0.001 | 50277 (29.0%) | 10325 (18.9%) | <0.001 |

| Mortality within 24 hours | 56116 (14.5%) | 20858 (8.6%) | 35258 (24.2%) | <0.001 | 19025 (11.0%) | 1295 (2.4%) | <0.001 |

| Mortality within 48 hours | 74286 (19.2%) | 27662 (11.5%) | 46624 (32.1%) | <0.001 | 24963 (14.4%) | 1990 (3.6%) | <0.001 |

| Mortality within 1 week | 113049 (29.2%) | 45342 (18.8%) | 67708 (46.5%) | <0.001 | 38826 (22.4%) | 5194 (9.5%) | <0.001 |

Figure 2.

Trends in mortality by coronary revascularization strategy among patients with MI and cardiogenic shock

In a propensity-matched analysis of 19,882 patients hospitalized for MI with cardiogenic shock who underwent coronary revascularization, CABG (without PCI) was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than PCI alone (19.0% vs. 27.0%, p<0.001) (Supplemental Figure 2, Supplemental Tables 4 & 5). Similar findings were observed in subgroups of matched patients with STEMI and NSTEMI, and in a sensitivity analysis after excluding patients with early mortality within 24 hours of admission. The association between coronary revascularization with CABG and lower in-hospital mortality was also observed in a sensitivity analysis of patients who presented with MI and cardiogenic shock in the era of second-generation drug eluting stents from 2010 to 2014. In a sensitivity analysis of matched patients undergoing coronary revascularization on the day of hospital admission, CABG (without PCI) was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than PCI alone (Supplemental Table 5).

Discussion:

In this analysis of US hospital admissions for MI and cardiogenic shock from 2002–2014, all-cause in-hospital mortality was 36.9%. Overall, only 62.4% of patients underwent coronary revascularization for MI and cardiogenic shock, with increases in rates of revascularization over time. Patients who underwent coronary revascularization had favorable survival compared to patients who received medical management alone.

As previously reported, we observed that in-hospital mortality remained unchanged over time in patients who underwent PCI for MI and cardiogenic shock. Data from the NCDR Cath-PCI Registry suggest that mortality rates after PCI for MI and cardiogenic shock may have actually increased between 2005–2006 and 2011–2013.12 Furthermore, three large randomized trials that enrolled patients with MI and cardiogenic undergoing infarct-vessel only coronary revascularization over two decades of clinical practice reported similar mortality.1,2,4 The failure of multi-vessel PCI to reduce mortality compared with culprit lesion only PCI also reaffirms the need for novel approaches to coronary revascularization to improve outcomes in MI and cardiogenic shock.

In the present study, among patients who underwent coronary revascularization, we observed that patients who were selected to undergo CABG had a significantly lower mortality than those who underwent PCI. Even after propensity score matching by demographics, clinical characteristics, hospital characteristics, and MI presentation, CABG was associated with improved in-hospital survival compared with PCI.

Findings from the present study are consistent with observational data from randomized trials and large registries.9,10 In the landmark Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) trial, early revascularization of the infarct artery in MI and cardiogenic shock reduced all-cause mortality at 6 months compared with initial medical stabilization (50.3% vs. 63.1%).1 In the SHOCK trial, immediate coronary revascularization with emergency CABG was recommended for all patients with angiographically severe left main or multi-vessel CAD, although the method of revascularization was ultimately determined by the treating physicians. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty of the infarct artery was performed in 54.6% of SHOCK trial participants assigned to coronary revascularization and CABG was performed in 37.5% of participants. Interestingly, SHOCK trial participants who underwent early CABG had a greater burden of CAD and twice the prevalence of diabetes mellitus than those who underwent PCI, but survival at 30 days was similar with PCI and CABG (55.6% with PCI vs. 57.4% with CABG, p=0.86).9

Other observational data suggest that CABG may be associated with lower mortality compared with PCI for patients with MI, multi-vessel CAD, and cardiogenic shock. In a small observational study of 88 propensity-matched patients with STEMI and cardiogenic shock, PCI followed by CABG was associated with lower 30-day mortality than PCI alone (20.5% vs. 40.9%, p = 0.03).10 Among 14,956 patients with pre-operative cardiogenic shock undergoing CABG who were included in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Database, 30-day mortality was 22%.13 Advanced age, female sex, need for concomitant valve surgery or ventricular septal repair, renal dysfunction, immunosuppression, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, prior cardiac surgery, recent MI, pre-operative cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and IABP use were independently associated with mortality after CABG. Among 5,496 patients with MI and cardiogenic shock who required MCS and were referred for CABG, 30-day mortality was 37.2% in those who required pre-operative MCS and 58.4% when post-operative circulatory support was required.14 These data demonstrate the feasibility of CABG in the setting of cardiogenic shock and suggest that surgical outcomes may be equivalent or superior to those associated with PCI.

There are a number of plausible explanations for the observed association between CABG and lower mortality in the setting of cardiogenic shock. First, complete revascularization is feasible with CABG, even in the setting of chronic total occlusions or complex or calcified CAD. Complete revascularization may facilitate improved function of viable myocardium and is associated with superior outcomes in patients with and without MI in the absence of cardiogenic shock.15,16 Second, on-pump CABG involves arresting the heart with cardioplegia, cooling the myocardium, and providing ventricular unloading through complete circulatory and hemodynamic support. These maneuvers provide myocardial rest during surgery and decrease myocardial oxygen requirements prior to revascularization, which may salvage at-risk ischemic myocardium. Furthermore, cardiopulmonary bypass during surgery reverses global ischemia and sustains perfusion to critical organs, which may abrogate the cascade of events leading to systemic inflammation and progressive hemodynamic decline in cardiogenic shock.17 Additional investigation of the role for CABG in patients with MI and cardiogenic shock is warranted.

Limitations:

There are a number of inherent limitations to evaluation of non-randomized data that must be recognized. The current analysis was based on ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes from a large administrative database, which are potentially subject to misclassification and/or miscoding. We were unable to adjudicate the diagnosis or severity of cardiogenic shock, and definitions used may have varied by clinical provider. Still, this large administrative database may identify a representative cohort of patients with cardiogenic shock in the United States. The proportion of women among patients with MI and cardiogenic shock in the present analysis (39%) is comparable to that reported in the SHOCK Registry (43%),18 and is greater than the proportion of women recruited in prior randomized trials of cardiogenic shock (24% - 32%).1,2,4,5 Although we performed propensity matching to account for baseline differences in characteristics of patients referred for PCI and CABG, there is undoubtedly residual selection bias and unmeasured confounding by indication for CABG. This selection bias may reflect changing practice patterns over time, suggested by the declining mortality in the cohort of patients referred for CABG. Nonetheless, CABG was associated with lower mortality than PCI at all time points and in all subgroups studied. Unfortunately, the timing between onset of MI, the onset of cardiogenic shock, and timing of coronary revascularization were not recorded. Survivor bias also likely impacts the findings of this analysis, although lower mortality after CABG was also observed in a sensitivity analysis that excluded all patients who died within the first 24 hours of the hospitalization with MI and cardiogenic shock. Unfortunately, coronary anatomy, including the presence of left main disease, could not be determined from this administrative database, although if a greater extent of CAD or more complex coronary anatomy was present in patients referred for CABG than those who underwent PCI, this would bias the study findings toward the null hypothesis. Similarly, details regarding the coronary revascularization, such as the use of arterial grafts during CABG, the number and location of coronary stents placed during PCI, or completeness of revascularization were not reported. Although patients who underwent CABG were more likely to be treated with IABP support and less likely to be treated with percutaneous left ventricular assist device or ECMO compared to patients who underwent PCI, the timing and duration of MCS cannot be determined from administrative data. Prospective clinical trials studying the use of MCS in cardiogenic shock are necessary. Finally, only in-hospital mortality was available from the NIS; long-term outcomes could not be determined. However, the majority of deaths in MI with cardiogenic shock occur in-hospital, with relatively few events among patients who survive to discharge from the index hospitalization. Therefore, observed differences in early mortality associated with CABG would be expected to confer a durable survival benefit.

To our knowledge, this is the largest observational analysis comparing CABG to PCI in patients with cardiogenic shock. Despite the limitations of observational analyses and the likelihood of residual confounding, the current investigation provides compelling preliminary data to support further investigation of CABG as a revascularization strategy in patients with MI, multi-vessel CAD, and cardiogenic shock. Efforts to define the optimal revascularization strategy of MI complicated by cardiogenic shock are necessary in light of the persistently high mortality rate with PCI and disappointing worse outcomes with multivessel PCI.4 A prospective registry, with detailed timing, hemodynamic and laboratory data would provide further insights on the role of PCI and CABG in cardiogenic shock compared to this large administrative database. Ultimately, a randomized clinical trial will be required to address this important clinical question.19

Conclusions:

Among patients admitted with MI and cardiogenic shock in the United States, coronary revascularization was associated with improved survival to hospital discharge, and CABG was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than PCI. These data support efforts to assess whether CABG is superior to PCI in prospective registries and a randomized trial of PCI versus CABG in patients with MI, cardiogenic shock, and multi-vessel coronary artery disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS) is associated with high mortality.

Coronary revascularization for MI and CS increased over time

Revascularization for MI and CS was achieved by PCI in 44.9% and CABG in 14.1%.

CABG was associated with lower in-hospital mortality than PCI for MI and CS.

Confirmation of this finding in a prospective registry or clinical trial is warranted.

Sponsor / Funding:

Dr. Smilowitz is supported in part by an NYU CTSA grant, UL1 TR001445 and KL2 TR001446, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors report no relationships that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(9):625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1287–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg RJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J. Thirty-year trends (1975 to 2005) in the magnitude of, management of, and hospital death rates associated with cardiogenic shock in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Circulation. 2009;119(9):1211–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiele H, Akin I, Sandri M, et al. PCI Strategies in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(25):2419–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Investigators T, Alexander JH, Reynolds HR, et al. Effect of tilarginine acetate in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock: the TRIUMPH randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297(15):1657–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah M, Patnaik S, Patel B, et al. Trends in mechanical circulatory support use and hospital mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction and noninfarction related cardiogenic shock in the United States. Clin Res Cardiol. 2018;107(4):287–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg DD, Bohula EA, van Diepen S, et al. Epidemiology of Shock in Contemporary Cardiac Intensive Care Units. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(3):e005618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb JG, Lowe AM, Sanborn TA, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock in the SHOCK trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(8):1380–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White HD, Assmann SF, Sanborn TA, et al. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results from the Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):1992–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu FC, Chang SN, Lin JW, Hwang JJ, Chen YS. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery provides better survival in patients with acute coronary syndrome or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction experiencing cardiogenic shock after percutaneous coronary intervention: a propensity score analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138(6):1326–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smilowitz NR, Gupta N, Guo Y, Berger JS, Bangalore S. Perioperative acute myocardial infarction associated with non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(31):2409–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wayangankar SA, Bangalore S, McCoy LA, et al. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Interventions for Cardiogenic Shock in the Setting of Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Report From the CathPCI Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(4):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta RH, Grab JD, O’Brien SM, et al. Clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of patients with cardiogenic shock undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery: insights from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Database. Circulation. 2008;117(7):876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acharya D, Gulack BC, Loyaga-Rendon RY, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients With Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery: Data From The Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(2):558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1411–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farooq V, Serruys PW, Bourantas CV, et al. Quantification of incomplete revascularization and its association with five-year mortality in the synergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with taxus and cardiac surgery (SYNTAX) trial validation of the residual SYNTAX score. Circulation. 2013;128(2):141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esposito ML, Kapur NK. Acute mechanical circulatory support for cardiogenic shock: the “door to support” time. F1000Res. 2017;6:737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochman JS, Boland J, Sleeper LA, et al. Current spectrum of cardiogenic shock and effect of early revascularization on mortality. Results of an International Registry. SHOCK Registry Investigators. Circulation. 1995;91(3):873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coronary Revascularization Strategies in Patients with Myocardial Infarction, Multi-vessel Coronary Artery Disease, and Cardiogenic Shock. http://www.is.gd/CABG_SHOCK.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.