Abstract

Rationale.

A growing body of transgender (trans) health research has explored the relationship between stigma and health; yet, studies have conceptualized and operationalized anti-trans stigma in multiple ways.

Objective.

This scoping review aims to critically analyze quantitative measures of anti-trans stigma in the U.S. using a socioecological framework.

Method.

We organized and appraised measures from 126 included articles according to socioecological level: structural, interpersonal, or individual.

Results.

Of the identified articles, 36 measured anti-trans stigma at the structural level (i.e., institutional structures and policies), 102 measured anti-transat the interpersonal level (i.e., community interactions), and 44 measured anti-trans stigma at the individual level (i.e., internalized or anticipated stigma). Definitions of anti-trans stigma varied substantially across articles. Most measures were adapted from measures developed for other populations (i.e., sexual minorities) and were not previously validated for trans samples.

Conclusions.

Studies analyzing anti-trans stigma should concretely define anti-trans stigma. There is a need to develop measures of anti-trans stigma at all socioecological levels informed by the lived experiences of trans people.

Introduction

Stigma occurs when institutions and individuals label, stereotype, and ostracize groups of people thereby preventing their access to social, economic, and political power (Link & Phelan, 2001). A critical review assessed how stigma operates as a social determinant of health for transgender people (White Hughto et al., 2015). Broadly, transgender (trans) describes individuals whose gender identity or expression does not align with culturally held expectations for people who share their assigned sex at birth. Here, we use the term anti-trans stigma to encompass the multitude of ways in which cultural ideologies that strictly enforce the male/female gender binary systemically disadvantage trans people. Anti-trans stigma includes discrete events of discrimination, harassment, and victimization (experienced or enacted stigma), feelings of devaluation and expectations of hostility (felt, perceived or anticipated stigma), and the acceptance of negative beliefs about one’s own trans identity (internalized or self- stigma) (Herek, 2016).

Health researchers have used the socioecological framework as an organizational tool to analyze how cultural norms and institutions shape all manifestations of stigma and to identify key levels at which stigma reduction interventions have been or should be targeted (Cook et al., 2014; Engebretson, 2013; Stangl et al., 2013; White Hughto et al., 2015). This framework distinguishes stigma operating at the individual level (individual cognitions and behavior), interpersonal level (community interactions), and structural level (laws, policies, and institutional practices) (White Hughto et al., 2015).

While the White Hughto et al. (2015) review provides a valuable synthesis of the health literature on anti-trans stigma, it did not discuss how anti-trans stigma is defined, operationalized, or assessed in health research. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review using systematic search procedures to characterize the varying definitions and measures of anti-trans stigma employed in the current literature. The White Hughto et al. (2015) review furthermore called for research that strengthens the evidence linking anti-trans stigma to adverse health outcomes and develops interventions that reduce anti-trans stigma across socioecological levels (White Hughto et al., 2015). This review uses the socioecological framework to synthesize and critically analyze quantitative measures of anti-trans stigma used in behavioral and public health science to support future research that documents and alleviates the health impacts of anti-trans stigma.

Method

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the review, studies needed to measure anti-trans stigma from the perspective of trans participants. We focused on this perspective due to research demonstrating subjective experiences of stigma as proximal determinants of health (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013). Studies that examined stigma using samples of trans and cisgender (i.e., non-transgender) participants needed to present disaggregated data on the trans sub-sample to be included. We did not restrict the search criteria by study design and included all peer-reviewed, empirical studies published in English in our final search. In order to maintain the context of the White Hughto et al. (2015) review, we restricted the analysis to studies using quantitative measures of anti-trans stigma and samples recruited from the U.S. (White Hughto et al., 2015). This decision also served to prevent imparting U.S.- or Western-centric notions of gender identity and sexuality onto other cultures.

Literature search

The first author carried out an electronic search of PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Embase databases using a combination of two search strings to maximize efficiency and sensitivity (see supplemental materials). The first search string targeted studies using trans populations with terms such as “transgend*” and “gender identity disorder.” The second search string used terms related to general stigma and stigma specific to trans people including “discrim*”, “transphob*”, and “inequalit*” (Poteat et al., 2015). The final search included all articles published before December 31, 2019 and was conducted on July 11, 2019.

During the review process, we were not blind to any characteristics published in the studies including the identities of study authors and funding sources. After retrieving abstracts and discarding duplicate citations, the first author excluded studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria due to lack of empirical design or trans study sample. Roughly 10% of initial records were double screened to ensure consistency in identifying records for inclusion. In order to maximize sensitivity for this scoping review, we used a liberal screening process such that records deemed potentially relevant for inclusion were assessed for full-text review. The first author reviewed the full-text format of articles to assess their eligibility, determined whether they used at least one quantitative measure of anti-trans stigma, and noted whether their sample was U.S.-based. Studies that were initially ambiguous regarding eligibility criteria were tagged and subsequently reviewed by another author to determine inclusion. The first and last authors approved the final list of included studies; any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

For each included study, we recorded any definition of stigma, domain(s) of stigma evaluated (enacted/experienced, perceived, anticipated, internalized), description of the measure(s) used, setting associated with the measure (i.e., healthcare, social services, workplace), and limitations about the measure noted in text.

Results

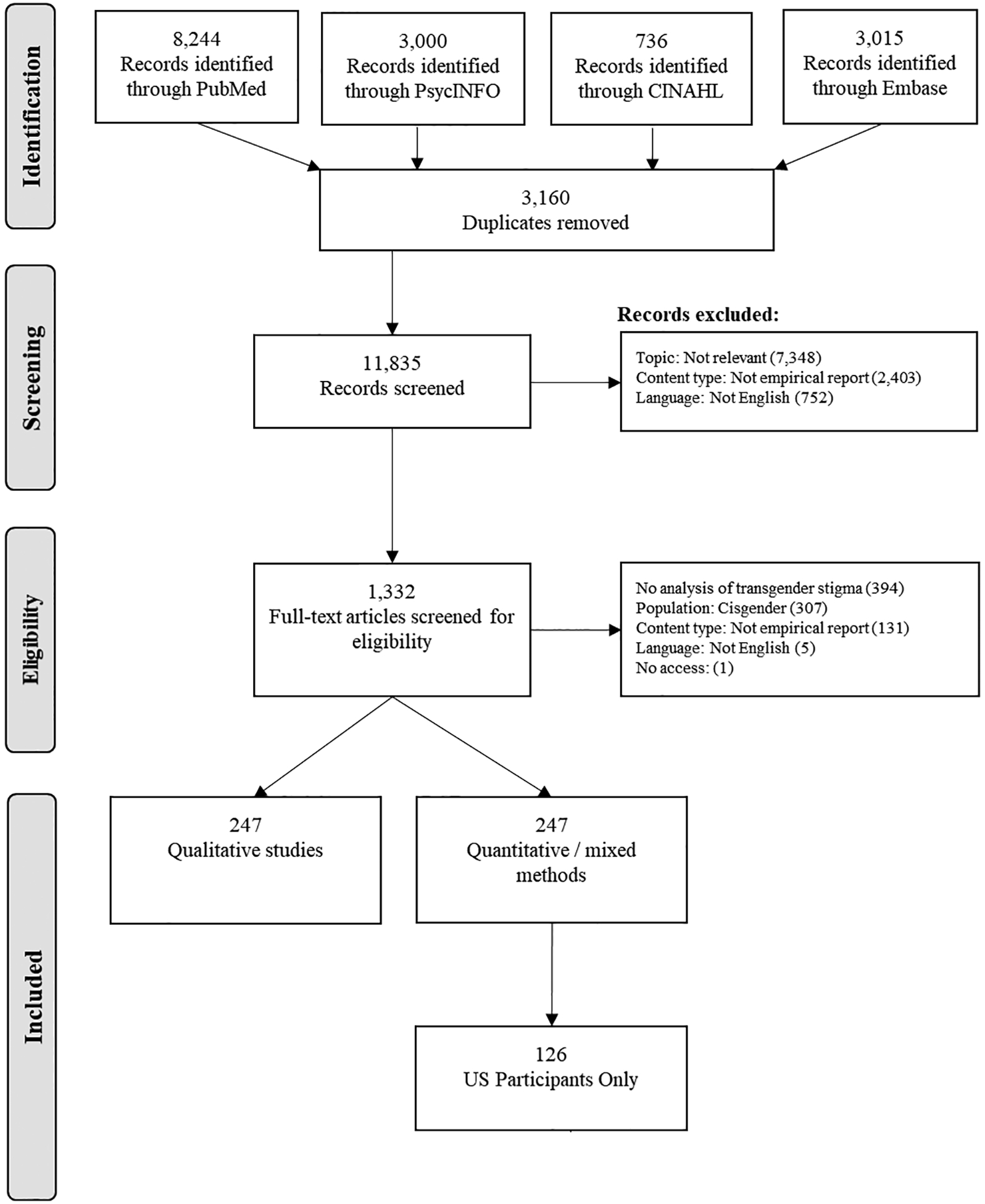

Searches of PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Embase retrieved 14,995 research articles. As shown in Figure 1, after removing duplicates, 11,835 articles remained. We excluded 10,503 based on abstract review because they were not relevant (k = 7,348), not empirical reports (k = 2,403), or not in English (k = 752). We retrieved full-text versions of the remaining 1,333 articles. Of these, 495 met eligibility criteria, and 248 used at least one quantitative measure of trans stigma. The most common reasons for excluding articles at this stage were for not analyzing anti-trans stigma and for having an entirely cisgender sample. This article reviews the 126 eligible studies that included only participants from the U.S. These studies represented 70 unique samples.

Fig. 1:

Flow diagram of included and excluded records.

We present measures of anti-trans stigma in alignment with the socioecological model (White Hughto et al., 2015). Measures of structural stigma quantify anti-trans experiences occurring at an organizational and policy level when trans individuals interact with institutions such as shelters, hospitals, and schools. Measures of interpersonal stigma are those that evaluate anti-trans stigma occurring during interactions with family members, employers, healthcare providers, or other individuals. Interpersonal stigma encompasses experiences of violence, harassment, and rejection due to gender identity or expression. In this review, we consider all anti-trans interactions between a cisgender individual and a trans individual to constitute interpersonal stigma even if they take place in institutional settings such as doctor’s offices, schools, or the workplace. Finally, measures of individual stigma reflect internalized negative beliefs about one’s own trans identity and behavioral avoidance of future stigma.

Most articles included in this review present results from studies that exclusively sampled trans participants (k = 102). Of these, 27 included only trans women or transfeminine participants, and eight included only trans men or transmasculine participants. Twelve studies recruited lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT) participants, and six also included heterosexual participants. Finally, eight studies included both trans women and cisgender men; these men were either men who have sex with men (MSM) or the partners of trans women. See supplemental materials for detailed information on study samples, anti-trans stigma measure descriptions, and any validity or reliability information reported for each measure.

The results are first organized by socioecological level. Within each level, we first review definitions of anti-trans stigma used in included studies. Then, we describe specific measures based on whether they were adapted from use with other populations or originally developed for trans populations. As reports from large-scale health surveillance studies do not detail the process of measure creation or selection, we present measures from these studies in a third section within each level.

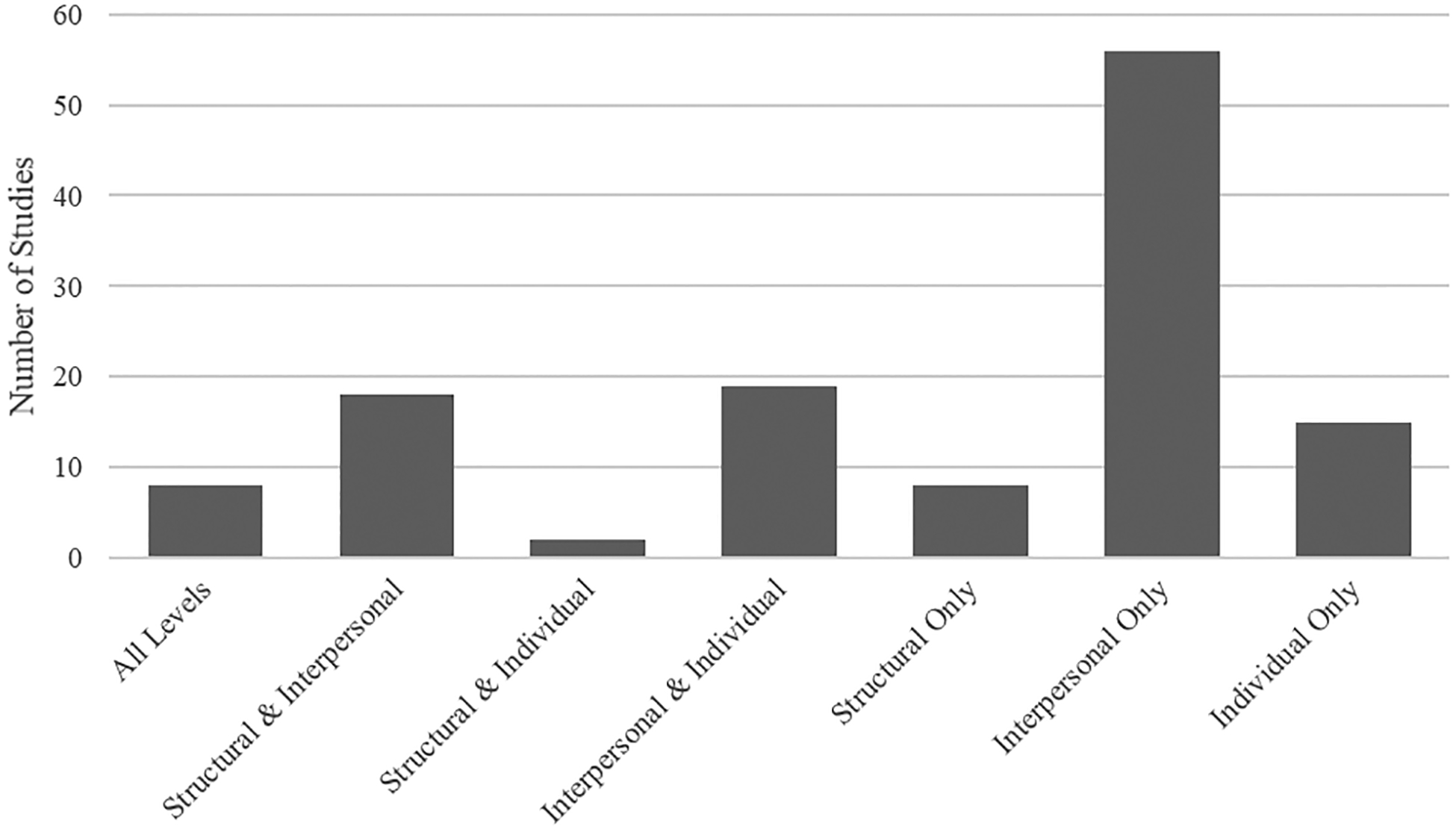

Some studies (k = 48) employed measures of anti-trans stigma spanning socioecological levels. Eight of these studies measured anti-trans stigma at all socioecological levels. Forty measured anti-trans stigma at two levels: 19 at the interpersonal and individual levels, 19 at the structural and interpersonal levels, and two at the structural and individual levels (Figure 2). These measures and studies are presented in two or more sections of the results as appropriate.

Fig. 2,

Proportions of included studies that measured stigma at each socioecological level.

Level 1: Structural

Definitions.

Of 126 included articles, 35 measured anti-trans stigma at the structural level. Of these, four articulated a specific definition of structural anti-trans stigma. One study mentioned that trans women face “systemic oppression” in addition to interpersonal and individual forms of stigma (Arayasirikul et al., 2017). A second study referenced institutional policies that limit trans people’s access to employment, education, housing, and other public services and constitute “transphobic discrimination” (Bauermeister et al., 2016). The final two definitions focused on how social groups devalue and marginalize people with socially undesirable characteristics in order to reinforce dynamics of power and control (Martinez-Velez et al., 2019; McLemore, 2018).

Adapted measures.

Four studies adapted or used measures of sexual minority stigma. Three of these studies included only trans participants and used adapted measures of discrimination among sexual minority military service members and employment discrimination (Beckman et al., 2018; Ruggs et al., 2015; Tucker et al., 2018). In the remaining study, both trans female and cisgender MSM indicated whether they had experienced workplace discrimination events “as a result of their sexuality” in the past year, with no language referencing gender identity (Bauermeister et al., 2016).

One study adapted the Experiences of Discrimination Scale, which was originally developed to assess racism, so that participants attributed each form of discrimination they endorsed to their race/ethnicity or gender identity/presentation (Baguso et al., 2019).

Of the five studies using adapted measures, none provided evidence for validity.

Original measures.

Eleven studies used original measures to assess structural stigma. A study of suicidality measured structural anti-trans stigma using two dichotomous-response items about lifetime housing and employment discrimination, and one study used a single item measure of discrimination in healthcare settings due to trans status (Frank et al., 2019; Lehavot et al., 2016). Another study developed a measure of “distal gender minority stressors” that included four dichotomous items about employment, housing, and healthcare discrimination (Arayasirikul et al., 2017). Clements-Nolle et al. (2006) created a similar measure with items regarding employment, housing, and healthcare that additionally asked participants to qualitatively describe the most recent event they experienced in each category (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006). Three subsequent studies used versions of this measure (Jackman et al., 2018; Reisner et al., 2017; Salazar et al., 2017).

The remaining studies developed measures that spanned structural and interpersonal levels of anti-trans stigma. One study developed the Service Utilization Barriers scale, which included a subscale for general “institutional/systemic barriers” to accessing mental health services (Shipherd et al., 2010). Another study developed the Perceptions of Aversiveness of Discrimination Scale, which asked about experienced stigma across housing, healthcare, employment, and several interpersonal domains due to gender identity and race/ethnicity (Erich et al., 2010). A third study measured experiences of transphobic discrimination in the following domains: poor treatment from parents/caregivers, faced difficulties obtaining employment, lost a job/career or education opportunity, changed schools and/or dropped out of school, or moved away from friends or family (Rowe et al., 2015). The fourth study defined healthcare discrimination as denial of service or two forms of interpersonal stigma due to sexual orientation or gender identity in a healthcare setting (Macapagal et al., 2016). Finally, one study asked participants to identify settings in which they had experienced discrimination, some of which were structural (e.g., in housing or healthcare) (Martinez-Velez et al., 2019).

Surveillance measures.

Fifteen studies investigating anti-trans stigma at the structural level were secondary analyses of data from the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS) or used items from the NTDS with different samples. Three of these studies analyzed single-item dichotomous-response measures of lifetime experiences of structural stigma (Begun & Kattari, 2016; Jaffee et al., 2016; White Hughto et al., 2017b). Two studies combined items related to housing, education and workplace discrimination indicative of structural anti-trans stigma; these measures were referred to as “structural discrimination” (Shires & Jaffee, 2016) and “major discrimination” (Miller & Grollman, 2015). Nine of the remaining studies investigated setting-specific structural stigma in the workplace, healthcare, carceral settings, and schools (Bakko, 2018; Drakeford, 2018; Glick et al., 2018; Liu & Wilkinson, 2017; Reisner et al., 2014a; Rodriguez et al., 2017; Romanelli et al., 2018; Seelman, 2014, 2016). Finally, one study used the Experiences of Transgender Discrimination Scale, which combines items regarding structural and interpersonal stigma taken from the NTDS (Staples et al., 2018). This measure was the only measure of structural anti-trans stigma with strong evidence of criterion validity; scores correlated with discomfort with police and worsening life, housing, and employment situations (Staples et al., 2018).

The remaining four studies measuring structural anti-trans stigma used data or measures from the One Colorado survey or the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study (THIS). Two analyses of THIS data used dichotomous measures of lifetime discrimination in healthcare, employment, and housing (Barboza et al., 2016; Bradford et al., 2013). A third study used THIS items to investigate discrimination in healthcare, employment, insurance, housing, and social services with a separate sample (Sevelius et al., 2019). Unlike in the NTDS and THIS surveys, the One Colorado survey asked whether discrimination was due to “sexual orientation or gender identity.” Participants were asked whether they had ever experienced employment and housing discrimination (Kattari et al., 2016).

Level 2: Interpersonal

Definitions.

Of the 126 included articles, 102 measured anti-trans stigma at the interpersonal level. Twenty-seven of these studies provided a conceptual definition. Most defined interpersonal anti-trans stigma as lived encounters with discrimination or inequitable treatment resulting from a cisgender individual’s prejudice towards trans people. These definitions relied on a broad range of examples of enacted or experienced stigma including psychological abuse, physical and sexual victimization and harassment, unfair treatment, romantic or familial rejection, and microaggressions. Notably, five studies defined interpersonal anti-trans stigma by referencing stigma faced by sexual minority populations, suggesting a lack of specificity and sensitivity to experiences of anti-trans stigma (Arayasirikul et al., 2017; Birkett et al., 2015; McCarthy et al., 2014; Nuttbrock et al., 2014; Sugano et al., 2006). For example, one study stated that transphobia is “analogous to homophobia” and defined transphobia as “societal discrimination and stigma of individuals who do not conform to traditional norms of sex and gender” (Sugano et al., 2006). Finally, five studies defined transphobia as an affective state using phrasing such as “an irrational fear of transgender people” despite measuring interpersonal anti-trans stigma from the perspective of trans participants (Hoxmeier & Madlem, 2018; Jefferson et al., 2014; Lombardi, 2009; Lombardi et al., 2002; Mizock & Mueser, 2014).

Adapted measures.

The majority (k = 55) of studies measuring interpersonal anti-trans stigma used measures adapted from other populations

From sexual minority stigma.

Of the 102 studies that measured interpersonal anti-trans stigma, 34 adapted measures of sexual minority stigma or homophobia, including the Daily Heterosexist Experiences Scale; the Heterosexist Harassment, Rejection, and Discrimination Scale (HHRDS); Diaz et al. (2001)’s homophobia scale (Diaz et al., 2001); and the Schedule for Heterosexist Events (for examples, see: (Bazargan & Galvan, 2012; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; Lehavot et al., 2016)). The adaptation process for these measures typically consisted of changing terminology (e.g., replacing “LGBT” with “trans”), but two studies added items specific to trans people. In one study, two items irrelevant to the experiences of trans youth from a measure of stigma developed for adult sexual minority women were replaced with items about discriminatory experiences at school and in bathrooms (Weinhardt et al., 2017). One study that adapted the HHRDS added “In the past year, how often have you been asked ‘what’s your real name’, ‘what are you really?’, ‘what is your birth sex?’” (Breslow et al., 2015). This measure was the only measure of interpersonal anti-trans stigma adapted from sexual minority populations for which researchers provided evidence of criterion validity; scores on this measure were correlated with awareness of public devaluation of trans people (Breslow et al., 2015; Brewster et al., 2019).

Other adapted measures from research with sexual minority populations did not cue participants to attribute stigma to their trans identity. In a version of the Perceived Discrimination and Violent Experiences, participants indicated the frequency with which “you were treated unfairly by employers, bosses, or supervisors” and “someone verbally insulted you or abused you” (McCarthy et al., 2014; Sugano et al., 2006). In a similar measure used in a study of trans women and MSM, items such as “I have experienced people acting as if they think I’m dishonest” were nonspecific about the source of the perceived disrespect (Sanchez et al., 2010).

From racism.

Nineteen measures of interpersonal anti-trans stigma were based in measures originally developed to quantify racism such as the Everyday Discrimination Scale. This scale assesses the frequency of various forms of discrimination such as “How often are you treated with less respect than others?”; yet, all studies modified this scale by either including “…because you are a transgender woman?” at the end of each item or by using another measure assessing participants’ attributions for discrimination (Bazargan & Galvan, 2012; Gamarel et al., 2014; Gamarel et al., 2018; Garthe et al., 2018; Hughto et al., 2018; Kidd et al., 2018; Kidd et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2019; Operario et al., 2014; Reisner et al., 2014b; Reisner et al., 2016b; White Hughto et al., 2017a; White Hughto & Reisner, 2018; Yang et al., 2015). Out of the 14 studies that used an adapted version of the Everyday Discrimination Scale, three provided evidence of validity. Two described using factor analysis to assess construct validity (Gamarel et al., 2018; Reisner et al., 2016b), and the third mentioned that the adapted measure was correlated with depressive distress, anxiety, and substance use in previous sexual and gender minority samples (White Hughto et al., 2017a).

Two studies adapted the Schedule of Racist Events, which was developed to quantify stressful experiences of racism and sexism in African American women. Sample items from the first adapted version included “How many times have you been treated unfairly by your employer, boss, or supervisors because you are transgender or transsexual?”(Lombardi, 2009). In the second adapted version, researchers substituted “…because you are a sexual minority?” at the end of each item. In this study of LGBT participants, trans participants received the same measure of discrimination as cisgender participants (House et al., 2011).

One study adapted the Experiences of Discrimination Scale by asking participants whether the experiences they endorsed were due to their race/ethnicity, gender identity/presentation, or both (Baguso et al., 2019). The final study adapted a measure of racial discrimination by substituting experiences the researchers viewed as specific to race with items specific to gender identity. For example, “discrimination in obtaining housing” was substituted with “having to move from family or friends” (Wilson et al., 2016).

From other forms of stigma.

One study adapted the Stigma Scale, originally developed for people with severe mental illness, using three subscales: Discrimination, Disclosure, and Positive Aspects of Being Transgender (Mizock & Mueser, 2014). A study of depressive symptoms adapted a measure of enacted stigma against HIV positive people that included items about receiving poorer service than others in public accommodations, and being denied or given lower quality healthcare, and being physically attacked or injured (Owen-Smith et al., 2017).

In a modification of the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire, researchers removed sex-specific items (i.e., abortion, miscarriage) and asked participants to indicate whether each life event they endorsed was due to their trans status (Shipherd et al., 2011). Similarly, in a modification of a criminal victimization measure, participants attributed their experiences of victimization, discrimination, or harassment to their perceived race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or another characteristic (Factor & Rothblum, 2007).

Original measures.

Twenty-five studies created their own measures of interpersonal anti-trans stigma. Seven studies used single items such as “Have you ever experienced discrimination by a doctor or other health care provider due to your transgender status and/or gender expression?” (Heima et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2017; Hoxmeier & Madlem, 2018; Keuroghlian et al., 2015; Reisner et al., 2013; Reisner et al., 2014c; Rowe et al., 2015). Another study asked participants if they had ever been the victim of violence or harassment due to being trans. Additionally, this study used a single-item dichotomous measure of workplace discrimination due to being trans (Lombardi et al., 2002).

Eleven studies used original, multi-item measures assessing interpersonal anti-trans stigma. Two studies asked participants to identify settings in which they had experienced discrimination (Martinez-Velez et al., 2019; Rood et al., 2018). In three studies, participants responded to items about verbal, physical, and sexual “gender victimization” in any setting throughout their lives (Bockting et al., 2013; Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Jackman et al., 2018). Only one study distinguished between different forms of exposure to stigma. Participants were asked to indicate if they had experienced any of five “anti-LGBTQ events” personally or witnessed the events, heard about the events firsthand, or heard about the events on social media or television (Veldhuis et al., 2018). Five studies used or created terms that fall under the umbrella of interpersonal anti-trans stigma and developed original measures of these constructs. These terms included gender abuse, gender related victimization, nonaffirmation of gender identity, and proximal [gender] minority stress (Arayasirikul et al., 2017; Klemmer et al., 2018; Nuttbrock et al., 2014; Nuttbrock et al., 2015; Tebbe et al., 2019). Regarding validity, one study developed a measure of transphobia based discrimination in consultation with a community advisory board (Klemmer et al., 2018), and one reported that scores on their measure were associated with general life stress, social anxiety, perceived burdensomeness, and belongingess (Tebbe et al. 2019).

The remaining measures quantified context-specific experiences of interpersonal anti-trans stigma. One study developed the Behavioral and Psychosocial Risk Survey to capture HIV risk in trans women; this measure included four items about teasing and harassment due to gender identity (Nemoto et al., 2005). Another study created the Transgender Persons Experiences Inventory, which asks about multiple forms of victimization and discrimination specific to Puerto Rican trans women (Rodríguez-Madera et al., 2017). In the only randomized control trial included in this review, researchers examined the frequency of stigma experienced by trans MSM during sexual encounters with cisgender MSM (Reisner et al., 2016a). Finally, one study developed an original measure of healthcare discrimination due to LGBTQ identity that included items regarding denial of equal service, unequal treatment, and verbal harassment in healthcare settings (Macapagal et al., 2016).

Three studies assessed the intersectional effects of anti-trans stigma and racism. One used the Perceptions of Aversiveness and Discrimination Scale, which assessed sixteen domains where interpersonal discrimination may occur (e.g., social services, interactions with police officers, family members) and asked participants to indicate whether endorsed experiences were due to race/ethnicity or “transsexual status” (Erich et al., 2010). The second study asked youth to indicate how frequently they were bullied due to gender, gender expression, and other identity attributes (Price-Feeney et al., 2018). The final study measured transphobia with a 13-item original scale, which the study did not describe (Jefferson et al., 2014).

Surveillance measures.

Twenty studies used NTDS data or items to investigate the relationship between interpersonal anti-trans stigma and health. Six of these analyzed responses to items concerning interpersonal discrimination, harassment, and victimization in public spaces (Glick et al., 2018; Liu & Wilkinson, 2017; Miller & Grollman, 2015; Reisner et al., 2014b; Reisner et al., 2015a; Reisner et al., 2015b; Shires & Jaffee, 2016). The NTDS included items about whether participants had been physically abused, verbally harassed, and/or denied equal treatment in healthcare and social service settings due to being trans. One study used all of these items to create a single indicator of discrimination (Bakko, 2018). Eight studies analyzed responses to the items concerning healthcare settings, which included doctor’s offices and hospitals, emergency rooms, mental health clinics, ambulances and EMTs, and drug treatment programs (Glick et al., 2018; Kattari & Hasche, 2016; Kattari et al., 2015; Liu & Wilkinson, 2017; Reisner et al., 2015a; Rodriguez et al., 2017; Shires & Jaffee, 2015; White Hughto et al., 2017b). Two studies measured experienced discrimination in domestic violence shelters/programs, rape crisis centers, and homeless shelters (Begun & Kattari, 2016; Seelman, 2015). Two studies analyzed data about interpersonal anti-trans stigma experienced while incarcerated (Drakeford, 2018; Reisner et al., 2014a), and the final about experiences with police (Salazar et al., 2017).

Three studies examined interpersonal stigma manifesting as family rejection. Participants were asked to indicate whether six events occurred with family members after coming out as trans/gender nonconforming such as “My parents or family chose not to speak with me or spend time with me” (Klein & Golub, 2016; Liu & Wilkinson, 2017; Seelman, 2015).

Two studies were secondary analyses of California Healthy Kids Survey data. These studies included trans and cisgender youth and analyzed data on bullying, safety concerns, harassment, and violence. Participants were asked to report the number of times they were bullied “because you are gay or lesbian or someone thought you are” and “because of your gender (being male or female)” (Coulter et al., 2018; Russell et al., 2011). Finally, two studies used THIS data. Participants answered items about six experiences of discrimination in healthcare, employment, and housing (Bradford et al., 2013; Rood et al., 2015).

Level 3: Individual

Definitions.

Forty-four of studies measured stigma at the individual level, which includes measurements of internalized transphobia and measurements of stigmatizing beliefs trans people anticipate or perceive cisgender people to hold. Eleven studies provided explicit definitions of individual stigma. In seven of these, definitions centered on the internalization of transphobic societal attitudes and adoption of a negative self-concept. Terms used to describe this phenomenon included identity stigma, self-stigmatization or self-stigma, and internalized transphobia, transphobic stigma, or transnegativity (Austin & Goodman, 2017; Breslow et al., 2015; Hoy-Ellis & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017; Jackman et al., 2018; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Perez-Brumer et al., 2015; Staples et al., 2018). Four studies defined anticipated stigma at the individual level, which was referred to as proximal stressor awareness, felt stigma, and perceived stigma. Two of these suggest that anticipated stigma must be a result of prior experience with interpersonal anti-trans stigma, while the others made no claims regarding a temporal relationship (Bell et al., 2018; Bockting et al., 2013; Breslow et al., 2015; Owen-Smith et al., 2017).

Adapted measures.

The majority (k = 25) of studies measuring anti-trans stigma at the individual level used adapted measures.

From sexual minority stigma.

Fourteen studies assessing internalized, anticipated, and/or perceived individual anti-trans stigma used adaptations of measures created for sexual minorities including the Homosexual Stigma Scale, Internalized Homophobia Scale, and the Outness Inventory Scale. The adaptation process in most studies consisted of terminology changes (Brewster et al., 2012; Brewster et al., 2019; Hoy-Ellis & Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2017; Hoy-Ellis et al., 2017; Macapagal et al., 2016; Raiford et al., 2016; Staples et al., 2018; Tucker et al., 2018). For example, in describing the adaptation process of the Internalized Homonegativity Subscale of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identity Scale, researchers stated, “[T]he word straight or heterosexual was replaced with cisgender in the following items ‘If it were possible, I would choose to be cisgender’ and ‘I wish I were cisgender’” (Tebbe & Moradi, 2016).

Three measures adapted from sexual minority stigma used general language rather than substituting trans-specific wording. Two studies used a scale that measures self-acceptance of LGBT identity to identify disparities in self-acceptance between trans people and cisgender LGB people; language in the items did not differentiate between sexual orientation and gender identity (McCarthy et al., 2014; Su et al., 2016). Another study used a measure of perceived stigma developed as part of a study of MSM to compare HIV risk in trans women with cisgender MSM (Sanchez et al., 2010).

Two separate studies modified the Internalized Homophobia Scale to develop their own measure called the Internalized Transphobia Scale. One version of an Internalized Transphobia Scale assessed three dimensions of internalized transphobia that emerged from confirmatory factor analysis: trans self-worth, trans identity and status in society, and maladaptive strategies to cope with trans identity (Austin & Goodman, 2017). The other version of an Internalized Transphobia Scale assessed public identification with trans identity, perception of stigma, social comfort with other trans people, and moral and religious acceptability (Mizock & Mueser, 2014).

From other forms of stigma.

Three measures of individual anti-trans stigma were adapted from HIV research. Two studies examined HIV risk behaviors in trans women using adaptations of the HIV-related Stigma Scale to operationalize perceived stigma and societal attitudes towards being trans (Golub et al., 2010; Raiford et al., 2016). The third study re-worded a single item measure taken from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance system to ask participants how strongly they felt that most people in their area tolerate trans people (Owen-Smith et al., 2017).

Other studies applied measures intended for general populations to trans participants. Two studies adapted the Public and Private subscales of the Collective Self-Esteem Scale by asking specifically about “gender identity group” (Breslow et al., 2015; McLemore, 2014). Four studies used an adaptation of the Stigma Consciousness Scale, which was developed to assess participants’ awareness of their group stereotypes (Bockting et al., 2013; Kidd et al., 2018; Kidd et al., 2019; Rood et al., 2018). Finally, one study changed the language of a single-item measure of dental fear to specify fear of discrimination due to trans status in dental care (Heima et al., 2017).

Two studies used adaptations of measures commonly used to study populations with severe mental illness. One study adapted the Devaluation-Discrimination Scale by replacing “former mental patient” with “transgender person” in items such as “Most people will pass over an application of a former mental patient in favor of another applicant” and the other took a similar approach to the Stigma Scale (McLemore, 2014; Mizock & Mueser, 2014). The former study also asked trans participants about cisgender people’s transphobia, with items such as “People are uncomfortable around others who don’t conform to traditional gender roles” (McLemore, 2014).

One study adapted the Perceived Stigma Scale, created for studies of parents of children with disabilities, to measure perceived stigma in an LGBT sample. Both trans and cisgender participants completed items about discrimination “because of [their] sexual orientation” (Bell et al., 2018).

Original measures.

Sixteen studies used measures of internalized anti-trans stigma developed specifically for trans populations. Six used all or part of the Transgender Identity Survey (TIS), developed with the input of a clinical trans sample and a panel of experts in trans health, and through confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis (Jackman et al., 2018; Perez-Brumer et al., 2015; Staples et al., 2018). The TIS comprised four subscales: pride (“Being transgender makes me feel special and unique”), passing (“It’s much better to pass than to be recognized as transgender”), alienation (“I am not like other transgender people”), and shame (“I sometimes resent my transgender identity”) (Bockting et al., 2013; Iantaffi & Bockting, 2011; Lehavot et al., 2016). Three studies used subscales of the Transgender Adaptation and Integration Measure (TG-AIM), which included three subscales: gender related fears, psychosocial impact of gender status, and gender locus of control. TG-AIM was previously found to correlate with self-esteem and quality of life among trans women (Salazar et al., 2017; Sanchez & Vilain, 2009; Tebbe & Moradi, 2016). One study developed the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure, which includes a subscale measuring “negative expectations for the future” that correlated with a variety of measures of psychosocial stress in tests of criterion validity (Tebbe et al., 2019). Finally, three studies used brief measures of ever avoiding healthcare due to anticipated discrimination (Lewis et al., 2019; Reisner et al., 2013; Shipherd et al., 2010).

Surveillance measures.

Measures of anti-trans stigma from large-scale health surveillance studies assessed anticipated stigma specific to healthcare settings. For example, the Trans Met Life Survey asked older LGBTIQ participants “how much confidence do you have that you will be treated with dignity and respect as an LGBTIQ person by your healthcare professionals at the end of your life?” (Walker et al., 2017). Several studies used dichotomous measures from the NTDS as indicators of anticipated stigma either in secondary analysis of NTDS data, secondary analysis of One Colorado data, or in original studies (Christian et al., 2018; Cruz, 2014; Glick et al., 2018; Macapagal et al., 2016; Reisner et al., 2015b; Seay et al., 2017; Seelman et al., 2017; White Hughto et al., 2016). For example, NTDS participants indicated whether they had ever “postponed or tried not to get needed medical care when I was sick or injured because of disrespect or discrimination from doctors or other healthcare providers” as a result of experiencing disrespect or discrimination based on gender (Jaffee et al., 2016).

Discussion

This is the first study to summarize quantitative measures of anti-trans stigma used in health research. Of the 126 studies included in this review, 35 measured anti-trans stigma at the structural level, 102 at the interpersonal level, and 44 at the individual level. Forty-eight of these studies measured multiple levels of anti-trans stigma (Figure 2). Across socioecological levels, most measures were adapted from other forms of stigma, including sexual minority stigma and racism. Adaptation usually consisted of changing item wording and removing items irrelevant to trans populations. Several studies reported on alpha reliability coefficients of adapted measures and described factor analysis procedures as evidence for internal consistency among scale items, but additional information to support the psychometric properties of measures was generally unreported (Sijtsma, 2009). Only one study provided evidence for criterion validity among trans samples for an adapted measure (Brewster et al., 2019). Original measures sought to capture stigma specific to trans people. In secondary analyses of surveillance surveys, researchers frequently created composite measures of anti-trans stigma by combining items assessing stigma across socioecological levels.

Few studies provided a definition for the anti-trans stigma construct they were measuring at any socioecological level. This definitional imprecision suggests that health researchers may be unclear about the varied manifestations of anti-trans stigma perceived or experienced by trans people, including how anti-trans stigma differs from other stigmas (e.g., sexual minority stigma), and how anti-trans stigma is relevant to their study outcomes. Many studies provided examples of anti-trans stigma in lieu of definitions of the concept or construct. Without a clear definition aligned with a conceptual framework of anti-trans stigma (or whichever related terms authors prefer), it is difficult to draw conclusions about the relationship anti-trans stigma has with other variables in the study.

Adapted measures

Measures adapted from other populations to assess anti-trans stigma varied widely in breadth, depth, and complexity. While most originated from research with sexual minority populations, others came from research on stigma regarding mental illness, HIV, and race/ethnicity. The absence of documented adaptation protocols reflects a lack of understanding of the unique forms anti-trans stigma takes and compromises measurement rigor. Several studies implicitly assumed that a measure validated for general LGB samples constitutes a valid measure for trans populations.

Furthermore, some researchers did not attempt to change the language used in measures of sexual minority stigma, thereby conflating gender identity and sexual orientation. One study assessing stigma in a sample of trans young adults asked participants to attribute negative events “…as a result of [your] sexuality?” (Bauermeister et al., 2016). Such wording puts trans participants in the position of having to either not report or misrepresent stigma they experience, regardless of whether they are sexual minorities in addition to being trans.

While paying close attention to biases in language is crucial, substituting wording that refers to sexual minorities or racial/ethnic groups with “transgender” or related terms does not constitute adaptation on its own. Some validated measures of sexual minority stigma originated from studies investigating effects of racism such as the Everyday Discrimination Scale and the Schedule of Racist Events. As noted in commentary on a previous review of measures of transphobia, continuously re-wording measures to reflect a new stigmatized group of interest reduces measures’ content validity (Billard, 2018). Furthermore, relying on surface-level changes to measurements serves to decentralize trans people and their experiences from the study of trans health.

Given the diversity of the trans population, validating a measure of anti-trans stigma with one sub-group does not justify its use with another. Measures developed and validated with trans women may not reflect the experiences of trans men or nonbinary individuals. As measures of other health constructs are routinely adapted for new geographic, linguistic, and cultural settings, measures of anti-trans stigma should be as well.

Original measures

Measures of stigma designed specifically for studying trans health were more reflective of trans perspectives than adapted measures as they often involved input from trans people. For example, Rodriguez et al. (2017) developed the Transgender Person’s Experiences Inventory, which includes questions about discrimination and violence, based on qualitative studies with trans women in San Juan (Rodríguez-Madera et al., 2017). The Transgender Person’s Experiences Inventory, TG-AIM, Transgender Identity Survey, and others specifically developed for trans health research acknowledge that trans people have unique experiences both in general and specifically regarding stigma.

Although most original measures sought to capture the experience of trans people, cisgender norms still pervaded these measures, particularly those quantifying internalized anti-trans stigma. For example, items such as “It’s much better to pass than be recognized as transgender” or “I wish I were cisgender” assume that endorsement reflects internalized transphobia rather than attempts to mitigate gender dysphoria, safety measures to avoid victimization, or autonomous acts of self-expression (Bockting et al., 2013; Iantaffi & Bockting, 2011; Lehavot et al., 2016; Sjoberg et al., 2008). Results may therefore reflect limited access to tolerant or affirming environments. Consequently, these measures might not necessarily quantify the extent to which trans participants have a negative self-concept of their trans identity.

At the other extreme, some measures asked participants to specify whether experiences of interpersonal stigma happened due to their perceived trans identity. Making such an attribution requires participants to analyze intentions and perceptions of the perpetrators. For example, in the NTDS, all questions were prefaced with phrasing specifying that reported experiences should be attributed to a participant’s trans identity. This might result in imprecise measurement as participants must speculate about the driving force behind experienced stigma.

Participants who hold multiple marginalized identities and youth may have difficulty attributing stigma to one specific identity. Intersectionality theory suggests that trans people who hold additional marginalized identities do not experience stigma additively; rather, stigma related to their other marginalized identities shapes the way cisgender institutions and individuals stigmatize their trans identity (and vice versa) (Crenshaw, 1989). For youth, developmental factors impacting participants and perpetrators such as egocentrism and difficulty with abstract thinking may further impede the ability to identify specific attributions for stigma. Developmentally appropriate measures that reflect the experiences of trans youth are needed to accurately capture anti-trans stigma in this population as none of the measures employed with youth in this review were worded or used examples specific to anti-trans stigma.

Surveillance measures

A sizable portion of included studies were secondary analyses of large-scale surveys of trans or LGBT health. These surveys, particularly the NTDS, included multiple dichotomous measures of lifetime discrimination experiences (e.g., healthcare, housing), which prevented conclusions about severity, frequency, or impact of trans discrimination.

Furthermore, many studies collapsed multiple nuanced measures into single-item indicators of discrimination. This approach conflates discriminatory experiences of different intensities. For example, one study combined experiences of physical abuse, verbal harassment, and denial of equal care experienced in healthcare settings into a single dichotomous variable (Barboza et al., 2016). Furthermore, some studies created composite measures that included items related to both structural and interpersonal stigma. By definition, structural stigma results in limited access to services necessary for health and wellbeing. Giving equal weight to reported experiences of structural stigma and interpersonal stigma within one measure fails to account for the socioecological relationship between the two. The effects of anti-trans institutional policies should be differentiated from the effects of anti-trans individuals in order to make meaningful suggestions as to how to mitigate the impact structural and interpersonal stigma have on health outcomes.

Limitations

Although this scoping review used a systematic approach to search and screen relevant publications, our results are limited by the sensitivity of our search strings and databases. We used four databases and comprehensive search strings used in previous systematic reviews. Yet, we double-screened only a small portion of records, did not use a front/back reference search, and did not search grey or unpublished literature, which may have resulted in the erroneous exclusion of some measures.

Additionally, we did not limit included articles by publication date. As a result, this review compares measures developed and implemented during different phases of academic understanding of trans identity and anti-trans stigma.

Regarding classification of the studies, lines between socioecological levels are blurred and complicated, especially when considering discrimination in institutional settings. It is debatable, for example, whether transphobic verbal harassment by a police officer constitutes interpersonal or structural stigma given the power dynamics at play. For the purposes of this review, we classified all stigma resulting from institutional policies or lack thereof as structural and all stigma resulting from the actions of individuals as interpersonal no matter their institutional affiliation. Yet, these generalizations result in interpretations that ignore the various ways anti-trans stigma traverses socioecological levels.

Finally, as U.S.-based concepts of gender and anti-trans stigma are not universal, the conclusions drawn in this review may not be applicable to other cultural contexts. Future reviews of anti-trans stigma measurements in global health literature are warranted.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations for researchers choosing or developing a measure of anti-trans stigma.

Use the gender binary as an organizing concept. In the context of the study population and research question, identify how continuous creation and enforcement of the gender binary generates anti-trans stigma across socioecological levels. Consider how multiple forms of stigma including experienced, anticipated, and perceived may arise for those who defy assumptions of the gender binary.

-

Clearly define the construct. Consult previous literature before writing a definition of anti-trans stigma in the context of the study. In keeping with the socioecological framework, the definition should encompass or reference structural, interpersonal, and individual stigma even if stigma will only be measured at one level in the study (White Hughto et al., 2015). Avoid comparisons between anti-trans stigma and stigma levied at other marginalized groups. State explicitly whether the investigation examines and measures stigma from the perspective of the stigmatized person/population (i.e., trans people) or from the perspective of the person/population expressing trans stigma (i.e., cisgender people).

As a starting place for future refinement, we offer the following definitions of anti-trans stigma at each socioecological level:- Structural: The systematic devaluation and marginalization of trans people that limits access to critical structural and social resources for wellbeing.

- Interpersonal: Behaviors, expressions, or intentions that indicate cisgenderindividuals’ consciously or unconsciously held negative attitudes and beliefs towards trans people including rejection, discrimination, harassment assault, and aggression on the basis of trans gender identity or expression.

- Individual: Person-level processes that reflect either (i) adaptation to and internalization of structural and interpersonal forms of anti-trans stigma (among trans people), or (ii) conscious or unconscious attitudes/beliefs and propensity to express structural or interpersonal forms of anti-trans stigma (among cisgender people).

Choose a measure. Considering the socioecological level(s) of interest and characteristics of the study design, choose an existing measure of stigma to adapt or draft items for an original measure. Create an initial version of the measure giving careful thought to which socioecological level encompasses each item, how each item reflects the definition of anti-trans stigma, and whether the items taken together represent the full universe anti-trans stigma under the definition.

Seek feedback. Trans people, including people similar to those in the future study and experts working in trans health, should be consulted to refine the measure and definition. As with any diverse population, experiences and preferred terminology differ across trans sub-groups, and items will need to be tailored to the study’s setting.

Test. Pilot the measure with trans participants who meet inclusion criteria of the future study and revise as necessary.

Conclusions

Anti-trans stigma has been incoherently defined in health research, and multiple measures have been used to quantify anti-trans stigma operating at the structural, interpersonal, and individual levels. These measures vary considerably in length, scope, and purpose, and few have been rigorously evaluated for validity with trans samples. This review calls for the development of new anti-trans stigma measures that span socioecological levels and are grounded in an understanding of how cisgender norms shape the lived experiences of trans people. Such measures need to be continuously revised to reflect changing terminology, conceptualizations of trans identity, and current political issues impacting trans people. The results of these validation efforts should be published or explicitly stated in the methods of future studies.

Supplementary Material

Research highlights.

First quantitative review of anti-trans stigma measures in the U.S.

Most studies measured interpersonal stigma; few measured structural stigma.

Only two of the 85 studies that adapted measures reported measurement validity.

Measures and definitions often conflated sexual orientation and gender identity.

Development of new measures should be grounded in trans-lived experiences of stigma.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Danielle Giovenco and Joella Adams for their assistance in developing an initial search strategy and screening protocol. Research was supported in part by U24AA22000

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arayasirikul S, Wilson E, & Raymond H (2017). Examining the effects of transphobic discrimination and race on HIV risk among transwomen in San Francisco. AIDS & Behavior, 21, 2628–2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, & Goodman R (2017). The impact of social connectedness and internalized transphobic stigma on self-esteem among transgender and gender non-conforming adults. J Homosex, 64, 825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baguso GN, Turner CM, Santos GM, Raymond HF, Dawson-Rose C, Lin J, et al. (2019). Successes and final challenges along the HIV care continuum with transwomen in San Francisco. J Int AIDS Soc, 22, e25270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakko M (2018). The effect of survival economy participation on transgender experiences of service provider discrimination. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: A Journal of the NSRC. [Google Scholar]

- Barboza GE, Dominguez S, & Chance E (2016). Physical victimization, gender identity and suicide risk among transgender men and women. Prev Med Rep, 4, 385–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Goldenberg T, Connochie D, Jadwin-Cakmak L, & Stephenson R (2016). Psychosocial disparities among racial/ethnic minority transgender young adults and young men who have sex with men living in Detroit. Transgend Health, 1, 279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, & Galvan F (2012). Perceived discrimination and depression among low-income Latina male-to-female transgender women. BMC Public Health, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman K, Shipherd J, Simpson T, & Lehavot K (2018). Military sexual assault in transgender veterans: Results from a nationwide survey. J Trauma Stress, 31, 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun S, & Kattari SK (2016). Conforming for survival: Associations between transgender visual conformity/passing and homelessness experiences. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services: The Quarterly Journal of Community & Clinical Practice, 28, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bell K, Rieger E, & Hirsch JK (2018). Eating disorder symptoms and proneness in gay men, lesbian women, and transgender and non-conforming adults: Comparative levels and a proposed mediational model. Front Psychol, 9, 2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benotsch EG, Zimmerman RS, Cathers L, Heck T, McNulty S, Pierce J, et al. (2016). Use of the internet to meet sexual partners, sexual risk behavior, and mental health in transgender adults. Arch Sex Behav, 45, 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billard TJ (2018). The crisis in content validity among existing measures of transphobia. Arch Sex Behav, 47, 1305–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B (2015). Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. J Adolesc Health, 56, 280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting W, Miner MH, Swineburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, & Coleman E (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health, 103, 943–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JB, Reisner S, Honnold JA, & Xavier J (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study. Am J Public Health, 103, 1820–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Velez BL, Wong S, Geiger E, & Soderstrom B (2015). Resilience and collective action: Exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers, 2, 253–265. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Velez B, DeBlaere C, & Moradi B (2012). Transgender individuals’ workplace experiences: The applicability of sexual minority measures and models. Counseling Psychology, 59, 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster ME, Velez BL, Breslow AS, & Geiger EF (2019). Unpacking body image concerns and disordered eating for transgender women: The roles of sexual objectification and minority stress. J Couns Psychol, 66, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, & Lehavot K (2019). Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social support and connection. LGBT Health, 6, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian R, Mellies AA, Bui AG, Lee R, Kattari L, & Gray C (2018). Measuring the health of an invisible population: Lessons from the Colorado Transgender Health Survey. J Gen Intern Med, 33, 1654–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, & Katz M (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons. J Homosex, 51, 53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Purdie-Vaughns V, Meyer IH, & Busch JTA (2014). Intervening within and across levels: A multilevel approach to stigma and public health. Soc Sci Med, 103, 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RWS, Bersamin M, Russell ST, & Mair C (2018). The effects of gender- and sexuality-based harassment on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender substance use disparities. J Adolesc Health, 62, 688–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz TM (2014). Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: A consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 76–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, & Marin BV (2001). The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 U.S. Cities. Am J Public Health, 91, 927–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakeford L (2018). Correctional policy and attempted suicide among transgender individuals. J Correct Health Care, 24, 171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebretson J (2013). Understanding stigma in chronic health conditions: Implications for nursing. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract, 25, 545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erich S, Tittsworth J, Cotlon Meier SL, & Lerman T (2010). Transsexual of color: Perceptions of discrimination based on transsexual status and race/ethnicity status. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6, 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- Factor R, & Rothblum E (2007). A study of transgender adults and their non-transgender siblings on demographic characteristics, social support, and experiences of violence. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3, 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Restar A, Kuhns L, Reisner S, Biello K, Garofalo R, et al. (2019). Unmet health care needs among young transgender women at risk for HIV transmission and acquisition in two urban U.S. Cities: The Lifeskills Study. Transgend Health, 4, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Cook-Daniels L, Kim H, Erosheva EA, Emlet CA, Hoy-Ellis CP, et al. (2013). Physical and mental health of transgeder older adults: An at-risk and underserved population. The Gerontologist, 54, 488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Mereish EH, Manning D, Iwamoto M, Operario D, & Nemoto T (2016). Minority stress, smoking patterns, and cessation attempts: Findings from a community-sample of transgender women in the San Francisco Bay Area. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 18, 306–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Reisner S, Laurenceau JP, Nemoto T, & Operario D (2014). Gender minority stress, mental health, and relationship quality: A dyadic investigation of transgender women and their cisgender male partners. J FAm Psychol, 28, 437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamarel KE, Sevelius JM, Reisner SL, Coats CS, Nemoto T, & Operario D (2018). Commitment, interpersonal stigma, and mental health in romantic relationships between transgender women and cisgender male partners. J Soc Pers Relat, 36, 2180–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthe RC, Hidalgo MA, Hereth J, Garofalo R, Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, et al. (2018). Prevalence and risk correlates of intimate partner violence among a multisite cohort of young transgender women. LGBT Health, 5, 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason HA, Livingston NA, Peters MM, Oost KM, Reely E, & Cochran BN (2016). Effects of state nondiscrimination laws on transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals’ perceived community stigma and mental health. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20, 350–362. [Google Scholar]

- Glick JL, Theall KP, Andrinopoulos KM, & Kendall C (2018). The role of discrimination in care postponement among trans-feminine individuals in the U.S. National Transgender Discrimination Survey. LGBT Health, 5, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg T, Jadwin-Cakmak L, & Harper GW (2018). Intimate partner violence among transgender youth: Associations with intrapersonal and structural factors. Violence Gend, 5, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, Walker JJ, Longmire-Avital B, Bimbi DS, & Parsons JT (2010). The role of religiosity, social support, and stress-related growth in protecting against HIV risk among transgender women. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cuase of population helath inequalities. Am J Pub Health, 103(5), 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heima M, Heaton LJ, Ng HH, & Roccoforte EC (2017). Dental fear among transgender individuals - a cross-sectional survey. Spec Care Dentist, 37, 212–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2016). A nuanced view of stigma for understanding and addressing sexual and gender minority health disparities. LGBT Health, 3, 397–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill BJ, Rosentel K, Bak T, Silverman M, Crosby R, Salazar L, et al. (2017). Exploring individual and structural factors associated with employment among young transgender women of color using a no-cost transgender legal resource center. Transgend Health, 2, 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House AS, Van Horn E, Coppeans C, & Stepleman LM (2011). Interpersonal trauma and discriminatory events as predictors of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender persons. Traumatology, 17, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxmeier JC, & Madlem M (2018). Discrimination and interpersonal violence: Reported experiences of trans undergraduate students. Violence Gend, 5, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy-Ellis CP, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Depression among transgender older adults: General and minority stress. Am J Community Psychol, 59, 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy-Ellis CP, Shiu C, Sullivan KM, Kim HJ, Sturges AM, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. Gerontologist, 57, S63–s71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughto JMW, Pachankis JE, & Reisner SL (2018). Healthcare mistreatment and avoidance in trans masculine adults: The mediating role of rejection sensitivity. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers, 5, 471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iantaffi I, & Bockting WO (2011). Views from both sides of the bridge? Gender, sexual legitimacy and transgender people’s experiences of relationships. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 13, 355–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman KB, Dolezal C, & Bockting WO (2018). Generational differences in internalized transnegativity and psychological distress among feminine spectrum transgender people. LGBT Health, 5, 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee KD, Shires DA, & Stroumsa D (2016). Discrimination and delayed health care among transgender women and men: Implications for improving medical education and health care delivery. Medical Care, 54, 1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson K, Neilands TB, & Sevelius J (2014). Transgender women of color: Discrimination and depression symptoms. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care, 6, 121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari S, & Hasche L (2016). Differences across age groups in transgender and gender nonconforming people’s experiences of health care discrimination, harassment, and victimization. Journal of Aging & Health, 28, 285–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari S, Walls N, Whitfield D, & Langenderfer-Magruder L (2015). Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender people in the United States. International Journal of Transgenderism, 16, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kattari S, Whitfield D, Walls N, Langenderfer-Magruder L, & Ramos D (2016). Policing gender through housing and employment discrimination: Comparison of discrimination experiences of transgender and cisgender LGBQ individuals. J Soc Social Work Res, 7, 427–447. [Google Scholar]

- Keuroghlian AS, Reisner SL, White JM, & Weiss RD (2015). Substance use and treatment of substance use disorders in a community sample of transgender adults. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 152, 139–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd JD, Dolezal C, & Bockting WO (2018). The relationship between tobacco use and legal document gender-marker change, hormone use, and gender-affirming surgery in a United States sample of trans-feminine and trans-masculine individuals: Implications for cardiovascular health. LGBT Health, 5, 401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd JD, Levin FR, Dolezal C, Hughes TL, & Bockting WO (2019). Understanding predictors of improvement in risky drinking in a U.S. multi-site, longitudinal cohort study of transgender individuals: Implications for culturally-tailored prevention and treatment efforts. Addict Behav, 96, 68–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, & Golub SA (2016). Family rejection as a predictor of suicide attempts and substance misuse among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. LGBT Health, 3, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemmer CL, Arayasirikul S, & Raymond HF (2018). Transphobia-based violence, depression, and anxiety in transgender women: The role of body satisfaction. J Interpers Violence, 886260518760015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koblin BA, Usher D, Nandi V, Tieu HV, Bravo E, Lucy D, et al. (2018). Post-exposure prophylaxis awareness, knowledge, access and use among three populations in New York City, 2016–17. AIDS Behav, 22, 2718–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, & Diaz EM (2009). Who, what, where, when, and why: Demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. J Youth Adolesc, 38, 976–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Simpson TL, & Shipherd JC (2016). Factors associated with suicidality among a national sample of transgender veterans. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior, 46, 507–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis NJW, Batra P, Misiolek BA, Rockafellow S, & Tupper C (2019). Transgender/gender nonconforming adults’ worries and coping actions related to discrimination: Relevance to pharmacist care. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 76, 512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol, 27, 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, & Wilkinson L (2017). Marital status and perceived discrimination among transgender people. Journal of Marriage and Family. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi EL (2009). Varities of transgender/transsexual lives and their relationship with transphobia. J Homosex, 56, 977–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi EL, Wilchins RA, Priesing D, & Malouf D (2002). Gender violence. J Homosex, 42, 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal K, Bhatia R, & Greene GJ (2016). Differences in healthcare access, use, and experiences within a community sample of racially diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning emerging adults. LGBT Health, 3, 434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Velez JJ, Melin K, & Rodriguez-Diaz CE (2019). A preliminary assessment of selected social determinants of health in a sample of transgender and gender nonconforming individuals in Puerto Rico. Transgend Health, 4, 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez LR, Sawyer KB, Thoroughgood CN, Ruggs EN, & Smith NA (2017). The importance of being “me”: The relation between authentic identity expression and transgender employees’ work-related attitudes and experiences. J Appl Psychol, 102, 215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MA, Fisher CF, Irwin JA, & Coleman JD (2014). Using the minority stress model to understand depression in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals in nebraska. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18, 346–360. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell MJ, Hughto JMW, & Reisner SL (2019). Risk and protective factors for mental health morbidity in a community sample of female-to-male trans-masculine adults. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLemore K (2014). Experiences with misgendering: Identity misclassification of transgender spectrum individuals. Self and Identity. [Google Scholar]

- McLemore K (2018). A minority stress perspective on transgender individuals’ experiences with misgendering. Stigma and Health, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LR, & Grollman EA (2015). The social costs of gender nonconformity for transgender adults: Implications for discrimination and health. Sociol Forum (Randolph N J), 30, 809–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, & Mueser KT (2014). Employment, mental health, internalized stigma, and coping with transphobia among transgender individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation & Gender Diversity, 1, 416–158. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Bodeker B, & Iwamoto M (2011). Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. Am J Public Health, 2011, 1980–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Operario D, Keatley J, Nguyen H, & Sugano E (2005). Promoting health for transgender women: Transgender resources and neighborhood space (trans) program in San Francisco. Am J Public Health, 95, 382–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Hwahng S, Mason M, Macri M, et al. (2014). Gender abuse and major depression among transgender women: A prospective study of vulnerability and resilience. Am J Public Health, 104, 2191–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, Hwahng S, Mason M, Macri M, et al. (2015). Transgender community involvement and the psychological impact of abuse among transgender women. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers, 2, 386–390. [Google Scholar]

- Operario D, Yang MF, Reisner S, Iwamoto M, & Nemoto T (2014). Stigma and the syndemic of HVI-related health risk behaviors in a diverse sample of transgender women. Journal of Community Psychology, 42, 544–557. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith AA, Sineath C, Sanchez T, Dea R, Giammattei S, Gillespie T, et al. (2017). Perception of community tolerance and prevalence of depression among transgender persons. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health, 21, 64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Oldenburg CE, & Bockting W (2015). Individual- and structural-level risk factors for suicide attempts among transgender adults. Behavioral Medicine, 41, 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Radix A, Borquez A, Silva-Santisteban A, Deutsch MB, et al. (2015). HIV risk and preventive interventions in transgender women sex workers. The Lancet, 385, 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price-Feeney M, Jones LM, Ybarra ML, & Mitchell KJ (2018). The relationship between bias-based peer victimization and depressive symptomatology across sexual and gender identity. Psychology of Violence, 8, 680–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiford JL, Hall GJ, Taylor RD, Bimbi DS, & Parsons JT (2016). The role of structural barriers in risky sexual behavior, victimization and readiness to change HIV/STI-related risk behavior among transgender women. AIDS Behav, 20, 2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Bailey Z, & Sevelius J (2014a). Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the US. Women Health, 54, 750–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Gamarel K, Dunham E, Hopwood R, & Hwahng S (2013). Female-to-male transmsculine adult health: A mixed-methods community-based needs assessment. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Assocation, 19, 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Gamarel K, Nemoto T, & Operario D (2014b). Dyadic effects of gender minority stressors in substance use behaviors among transgender women and their non-transgender male partners. Psychology of Sexual Orientation & Gender Diversity, 1, 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Hughto J, Dunham E, Heflin K, Begenyi J, Coffey-Esquivel J, et al. (2015a). Legal protections in public accommodations settings: A critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Milbank Q, 93, 484–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Hughto J, Pardee D, Kuhns L, Garofalo R, & Mimiaga M (2016a). Lifeskills for Men (LS4M): Pilot evaluation of a gender-affirmative HIV and STI prevention intervention for young adult transgender men who have sex with men. J Urban Health, 93, 189–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Jadwin-Cakmak L, White Hughto J, Martinez M, Salomon L, & Harper G (2017). Characterizing the HIV prevention and care continua in a sample of transgender youth in the U.S. AIDS & Behavior, 21, 3312–3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, Pardo S, Gamarel K, White Hughto J, Pardee D, & Keo-Meier C (2015b). Substance use to cope with stigma in healthcare among U.S. Female-to-male trans masculine adults. LGBT Health, 2, 324–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, White Hughto J, Gamarel K, Keuroghlian A, Mizock L, & Pachankis J (2016b). Discriminatory experiences associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among transgender adults. J Couns Psychol, 63, 509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S, White J, Bradford J, & Mimiaga M (2014c). Transgender health disparities: Comparing full cohort and nested matched-pair study designs in a community health center. LGBT Health, 1, 177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Madera SL, Padilla M, Varas-Díaz N, Neilands T, Guzzi ACV, Florenciani EJ, et al. (2017). Experiences of violence among transgender women in Puerto Rico: An underestimated problem. J Homosex, 64, 209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]