Abstract

Background:

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are important public health concerns among Black men who have sex with men only (BMSMO), as well as those who have sex with both men and women (BMSMW). STIs also increase risk for acquiring and HIV, which is also a critical concern. Compared to BMSMO, research shows that BMSMW experience elevated levels of HIV/STI vulnerability factors occurring at the intrapersonal, interpersonal and social/structural levels.1 These factors may work independently, increasing one’s risk for engaging in high risk sexual behaviors, but often work in a synergistic and reinforcing manner. The synergism and reinforcement of any combination of these factors is known as a syndemic, which increases HIV/STI risk.

Methods:

Data from the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 061 study (N=799) was used to conduct a latent profile analysis to identify unique combinations of risk factors that may form a syndemic and that may vary between BMSMO and BMSMW. We hypothesized that the convergence of syndemic factors would differ between groups and predict sexual risk and subsequent incident STI.

Results:

For BMSMO who had a high sexual risk profile the syndemic factors characterizing this group included perceived racism, incarceration, IPV, depression, and binge drinking. For BMSMW with a high sexual risk profile, the syndemic factors that characterized this group were incarceration, depression, and binge drinking.

Conclusions:

The current analysis highlights syndemic profiles that differentiated BMSMO and BMSMW from one another and support the need for tailored interventions that address specific syndemic factors for both subpopulations of BMSM.

Keywords: Syndemics, latent variables, STI, sexual minority men, African American

Short Summary:

The current study highlights syndemic profiles that differentiated BMSMO and BMSMW from one another and support the need for tailored interventions.

Introduction

HIV/STI are important public health concerns among Black men who have sex with men only (BMSMO), as well as those who have sex with both men and women (BMSMW) in the U.S., as well as globally. BMSMO and BMSMW represent approximately 72% of new HIV infections among all Black men and 25% of all new infections in the U.S., annually.1 STI rates among BMSM are higher than that of any other racial group with BMSM having 8.0 times the absolute increase in rates of STIs compared to white MSM.2 Currently, HIV prevention and treatment protocols are complex, requiring understanding of the complexities of vulnerability factors that increase risk and should aim at reducing STIs.

Many studies of BMSM treat BMSM as a monolithic group, resulting in unintentional lack of distinction between BMSMO and BMSMW. Aggregating both subpopulations of BMSM results in a lack of findings specific to BMSMW, and thus an absence of discussion related to this population. Despite this fact, BMSMW occupy a position of epidemiologic importance given elevated HIV/STI risk and potential to transmit HIV/STI to both male and female partners.3–8

HIV Prevention Trials Network 061 (HPTN061) studies have illustrated that compared to BMSMO, BMSMW experience elevated HIV/STI vulnerabilities, occurring at intrapersonal (e.g. depression, substance use),6,7 interpersonal (e.g. intimate partner violence (IPV)7 and trauma experiences),6 and social/structural levels (e.g. racism and incarceration).9,10 These factors may work independently, but often work in a manner known as a syndemic.

Syndemic theory posits that two or more vulnerability factors interact synergistically, overlap and co-occur, thereby increasing disease burden in certain subpopulations and may be important for predicting HIV/STI risk and incidence in MSMW,11 including those who are Black. However, understanding of syndemics and HIV/STI in this particular subgroup of men remains limited. First proposed by Singer in 1996, the SAVA syndemic of substance use, violence and AIDS was used to explain concurrent, reinforcing risk factors for HIV in a high-risk sample of adolescents.12 Since then, the theoretical framework has been applied to elucidate disproportionately high levels of HIV-risk behaviors and acquisition of HIV among sexual minority men.12–17

Extant literature supports that BMSM experience high levels of victimization including intimate partner violence18–22 and, subsequently, stress,18,23–26 depression,18,27–30 and substance use,18,31–34 all well-documented HIV risk factors among men including among BMSM.18–36 Specific to BMSM, literature has documented syndemics of depression, substance use, and violence that have been positively and additively associated with sexual risk behavior,37,38 such as condomless anal sex39 and with seroconversion.40

Another adverse experience disproportionately concentrated in Black men41–44 including BMSM and is a risk factor for HIV/STI45–50 is incarceration and ours is one of few studies in the literature to include incarceration as syndemic factor.51–53

While some BMSM may be exposed to any one of these factors increasing sexual risk and HIV/STI, these factors are highly correlated. BMSMW often report elevated levels of compound, interconnected factors (e.g., internalized homophobia, cocaine use) that correspond with increased risk and frequency of potential exposure to HIV.6,8,54 Given the varied experiences of both subpopulations of BMSM, syndemic profiles would also likely vary between the two groups.

Cumulative indices remain the most common methodology in assessing syndemics.13,55,56 These assume however, that each factor has equivalent impact on outcomes of interest, and that the number of factors represents a single unidimensional syndemic,57 so while intuitive, due to these assumptions they may not completely represent complex interactions of various psychosocial and structural factors. Different combinations of factors may have distinct effects on HIV/STI outcomes.57

Latent class analysis (LCA) has emerged as a popular approach to syndemic analysis, favored for its ability to simultaneously consider multiple factors that reveal grouping patterns emergent in the data,58–60 allowing for detection of unique combinations not detectable using a cumulative index. This method also avoids some key analytic limitations of interaction terms, including limited power when several interaction terms are present, and substantial difficulty detecting interactions beyond pairwise terms (e.g. three-way and four-way interactions), due to exponentially increasing sample size requirements for adequate power.61 LCA maintains utility even when measuring syndemics consisting of large numbers of factors. Latent profile analysis (LPA) is an analogous method with these same strengths but used with continuous indicators.

Purpose

Conceptually, the influence of syndemics on subsequent STIs is not a direct association; and is more than likely mediated through sexual risk behaviors lying along the causal pathway.40,62

We used data from HPTN061to conduct an LPA to test for a baseline syndemic of depression, racism, stimulant drug use, binge drinking, IPV and incarceration and its effect on 6-month sexual risk taking as a mediator to 12-month incident STI. We hypothesized that there would be unique combinations of risk factors that form a syndemic varying between BMSMO and BMSMW6 and that specific latent profiles would be associated with sexual risk and subsequent incident STI.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The HPTN061 study, a large multi-site longitudinal observational cohort study of BMSM in the United States has been previously described in detail63,64 and has been used in previous research on HIV among BMSM.4,65–68 HPTN061 aimed to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a HIV prevention intervention in six cities: Atlanta, Boston, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, and Washington, DC. Between July 2009 and October 2010, BMSM were recruited using methods such as direct field-based outreach, engagement of key informants and community groups, advertising through print and online media, and chat room outreach and social networking. Eligibility criteria included self-identification as a man or being male at birth and as Black, African American, Caribbean Black, or multiethnic Black; and at least one self-reported instance of condomless anal sex with a man in the past six months. Institutional review boards at the participating institutions approved the study.

Study Procedures

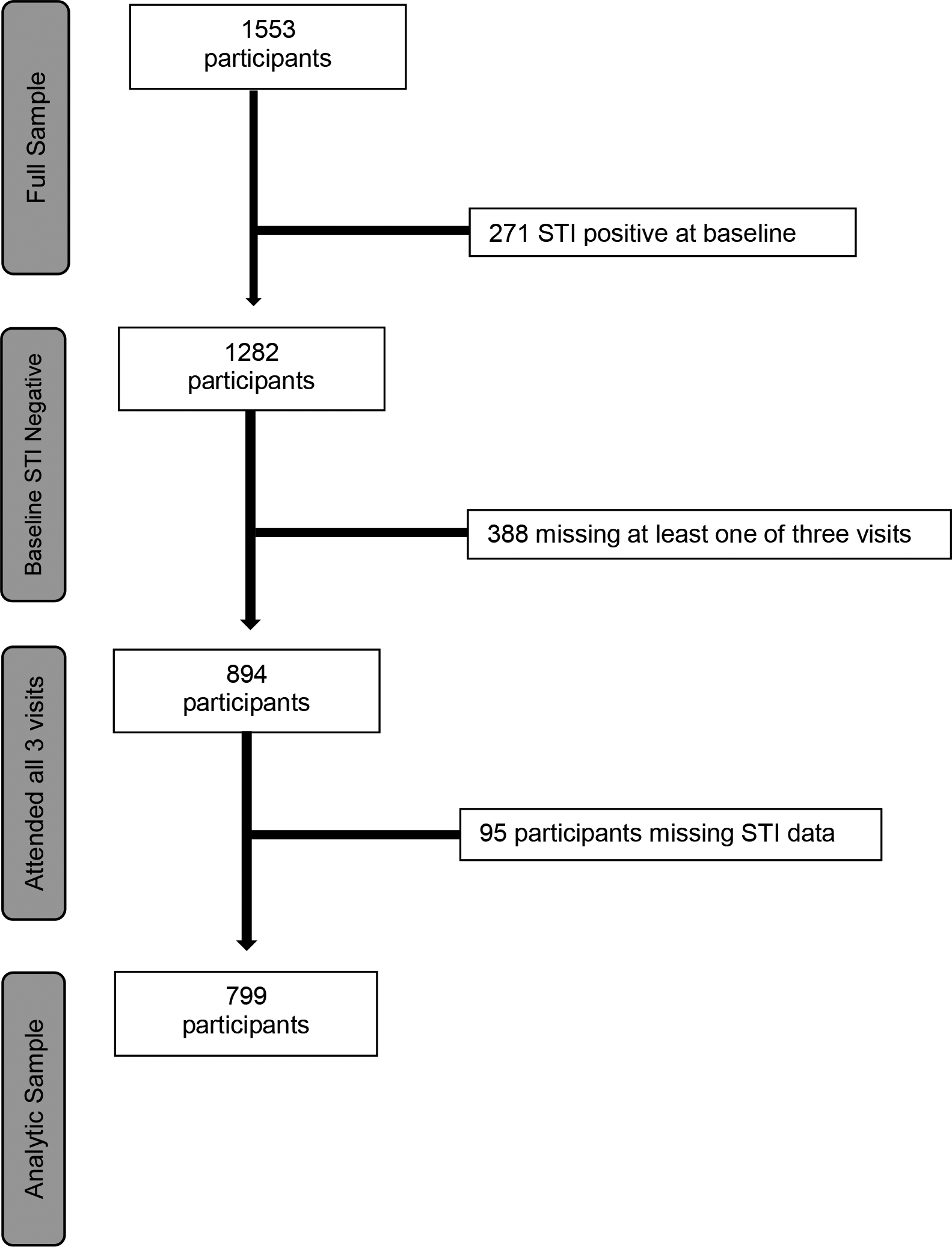

Self-reported data was collected through Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interviews (ACASI). Laboratory data was also collected. The initial sample consisted of 1553 participants. We included ONLY those STI negative at baseline, with all three study visits (enrollment, 6 and 12 months), and who were not missing STI data post-imputation, resulting in a final analytic sample of n=799 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart for LPA study analytic sample.

Measures

Syndemic Variables (All measured at baseline)

Perceived Racism

Lifetime perceived racism was measured using self-reported questions on 28 experiences of racism that covered several dimensions (e.g. disrespectful treatment, belittling and threats, and violence). For each item, participants selected if it “Happened to me because of my race” and selected how much it bothered them. Responses were coded as 0= “Doesn’t bother me at all”/ “Never happened,” to 4= “Bothers me extremely” and summed, creating a scale ranging from 0 to 112 (α =.94).

Incarceration

Lifetime incarceration history was measured in self-reported number of times spent in jail or prison for at least one night.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

IPV was measured in four items reflecting if participants had ever experienced emotional abuse, physical abuse, stalking, and forced sexual activity with an intimate partner.69 Responses were coded as 0= “Never happened,” 1= “Yes, but this has rarely happened”, 2= “Yes, this has sometimes happened,” 3= “Yes, this has happened often,” 4= “Yes, this has always happened.” Responses were summed, creating a scale ranging from 0 to 16. These items demonstrated high reliability (α =.81).

Trauma

Lifetime trauma exposure was measured using a 15-item index adapted from the Davidson Trauma Scale70 and included myriad events (e.g. seeing someone killed, home invasion). Each item was coded as 0= “Did not occur in the past 6 months,” 1= “Did occur in the past 6 months.” Responses were summed to produce an index ranging from 0 to 16 (α =.79).

Depression

Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-20) scale.71 This is a 20-item scale measuring depressive symptomatology, and covers several dimensions of depression, including feelings of sadness, undue effort accomplishing tasks, and lack of usual enjoyment. Responses were coded based on the number of days experiencing each item in the past week (Less than 1 day, 1–2 days, 3–4 days, 5–7 days). These items demonstrated high reliability (α =.89).

Stimulant Drug Use

Stimulant drug use (i.e., crack, cocaine, methamphetamines, amyl nitrites (poppers), and other stimulants) was measured as a 5-item index, with each response binary coded as 0= “No use in the past 6 months,” 1= “Use in the past 6 months.” Responses were summed; while reliability was relatively low (α = .51), all items demonstrated significant intercorrelations (Phi coefficient ranging from .06 to .29, p-value ranging from .027 to <.001).

Binge Drinking

Binge drinking was measured as the number of days in the past six months that the participant had six or more drinks on one occasion.72

Mediators and Outcomes

Sexual Risk Behaviors

Sexual risk behaviors were all binary and measured at 6 months after baseline. These included being drunk at last sexual intercourse, substance use at last sexual intercourse, any transactional sex (i.e. having given or received money, drugs, other goods or a place to stay the last time they had condomless anal intercourse), any condomless receptive anal intercourse (CRAI), and having three or more sexual partners in the past 6 months.

Incident STI

Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) were performed for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis using urine and rectal swab samples. Blood samples were tested for syphilis using serologic tests at each visit. A committee reviewed syphilis test results. For our analyses, we used 12-month STI status as our outcome, with a positive result for any STI being considered positive, and a negative result for all being considered negative.

Covariates

BMSMO/BMSMW Status

Given the entire cohort consisted of BMSM, participants were categorized as BMSMW if they reported any female sexual partners over the length of the study. Participants who reported no female partners were categorized as men who have sex with men only (BMSMO).

Other covariates

Other covariates were age, income and enrollment location.

Analyses

Missing Data

Missingness across all syndemic and sexual risk behavior variables ranged from 1% to 12%, with the majority of variables missing less than 4%. For all multi-item measures, we used intrascale stochastic imputation to impute missing items within scales/indices from other items. For binge drinking, we imputed missing binge drinking measures from other measures related to alcohol use in the study, which demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.84). All scales demonstrated strong internal consistency and/or significant intercorrelation of items, supporting the validity of using this means of imputation. After imputation, there was no variable with more than 4% missingness.

Latent Profile Analyses

We conducted an LPA stratified by BMSMO/BMSMW status to identify baseline latent syndemic profiles within each group. To determine the ideal number of profiles within each group, we compared a 2, 3, 4, and 5 profile model within each group. Model selection considered entropy (a measure of class separation, with values closer to 1 representing better fit), adjusted Vo-Lu-Mendel-Rubin likelihood ratio tests, and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) (representing the amount of information lost using the model, with a smaller BIC indicating better fit). Solutions were identified using 100 randomly generated seeds, and selecting the best fitting model in the majority of solutions. All analyses allowed for correlated residuals to address local interdependence of profiles. Participants were then assigned to profiles using the “classify-analyze” approach based on greatest posterior probability of profile membership. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis, comparing our LPA restricted to participants with complete follow-up to an LPA conducted on the unrestricted sample at baseline.

Bivariate Analyses

We used Cochran-Armitage tests of trend and Chi-square tests to assess differences in ordinal and binary syndemic factors, respectively across STI status. We also used Kruskal-Wallis tests and Chi-square tests to assess differences in ordinal and binary syndemic factors, respectively across latent profiles. Chi-square tests were used to assess differences in 6-month sexual risk behaviors across both 12-month STI status and baseline latent profiles. STI status was also tested across latent profiles using Chi-square tests.

Regression Analyses

Modified Poisson regression was used to generate risk ratios for 12-month incident STI. This method is appropriate for generating risk ratios for binary outcomes.73 Three models were generated: A model using the latent profiles only, a model adding terms for potential baseline confounders (age, site, education, income), and a model adding confounders and sexual risk behaviors as mediators (drinking at last intercourse, substance use at last intercourse, any transactional sex, CRAI, having three or more partners). All models used a scale parameter to correct for overdispersion. We also used domain statements to adjust for intercorrelations within sites. We assessed intercollinearity by measuring the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all models, there was none detected (all VIF<3).

Mediation Analyses

We used Vanderweele’s difference method, measuring the difference between estimates before and after adjusting for mediators.74 The presence of indirect associations indicated mediation was present. Statistical significance of indirect associations was assessed using bootstrapping with 1,000 repetitions to generate 95% confidence intervals.

Sensitivity Analyses

Investigating if participants lost to follow-up were systematically different from those retained, we tested if loss to follow up was associated with baseline syndemic factors (using Cochran-Armitage tests of trend), sexual risk behaviors (using Chi-square tests), or STI (using Chi-square tests with Yates correction).

Statistical Analysis

LPA’s were conducted in R 3.4.0 using the LPA package.75 All other analyses used SAS 9.4.76 All statistical analyses used a two-sided test of significance for inference.

Results

Sample Characteristics (Not illustrated)

At 12 months 3.9% of the sample tested positive for syphilis, 4.2% for chlamydia, and 2.2% for gonorrhea. Three and a half percent of the sample tested positive for chlamydia by rectal swab, 2.2% tested positive for gonorrhea by rectal swab and 0.6% of the sample tested positive for urogenital chlamydia, 0.4% tested positive for urogenital gonorrhea. Overall, 8.5% of the sample tested positive for any STI.

Univariate and Bivariate

Table 1 shows median baseline syndemic factors and 6-month sexual risk behaviors stratified by incident STI. Among the 414 BMSMO, 55 had an incident STI, while among BMSMW, only 13 had an incident STI. Nearly one-third of the sample reported being drunk at last intercourse, having used drugs at last intercourse, and engaging in CRAI. Just over half the sample had three or more sexual partners. There were no significant bivariate associations between syndemic components and incident STI, with the exception of greater median times incarcerated among BMSMO with incident STI compared to BMSMO with no incident STI. Only CRAI was associated with greater incident STI among both BMSMO and BMSMW. Additionally, in our post-hoc analysis there was no association between loss to follow up and any of these variables.

Table 1.

Proportions of baseline syndemic factors and 6 month sexual risk behaviors across 12 month STI incidence among Black men who have sex with men (n=799).

| Total | BMSMO (n=414) | BMSMW (n=385) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Incident STI (n=359) | Incident STI (n=55) | p value | No Incident STI (n=372) | Incident STI (n=13) | p value | ||

| Median Standardized Perceived Racism Index1 | 1.00 | 1.09 | 0.98 | .283 | 0.96 | 0.98 | .508 |

| Median Number of Times Incarcerated1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | .643 | 3 | 2 | .579 |

| Median Stimulant Use Index1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .214 | 1 | 0 | .771 |

| Median Intimate Partner Violence Index1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .207 | 0 | 2 | .075 |

| Median Standardized Depression Index1 | 14 | 13 | 12 | .429 | 14 | 20 | .489 |

| Median Trauma Index1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .233 | 1 | 1 | .341 |

| Median Number of Times Binge Drinking1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .401 | 1 | 1 | .463 |

| Percentage Drunk at last intercourse2 | 31.6% | 26.2% | 21.8% | .600 | 37.6% | 53.9% | .372 |

| Percentage used drugs at last intercourse2 | 27.7% | 20.6% | 14.6% | .385 | 36.3% | 38.5% | 1.000 |

| Percentage engaging in any transactional sex2 | 12.4% | 8.1% | 3.6% | .373 | 19.6% | 15.4% | .982 |

| Percentage engaging in any condomless receptive anal intercourse2 | 30.4% | 34.3% | 52.7% | .013 | 16.4% | 46.2% | .016 |

| Percentage with three or more sexual partners2 | 55.1% | 44.3% | 54.5% | .202 | 64.5% | 46.2% | .289 |

BMSMO = Black men who have sex with men only, BMSMW = Black men who have sex with men and women. Statistically significant (p<.05) estimates bolded.

Tested using Cochran-Armitage test of trend

Tested using Chi Square test with Yates Correction.

Latent Profile Analyses

All latent profile models demonstrated exceptionally high entropy (Table 2). Among BMSMO, two latent profile models were successfully fitted, a 2 and 3 profile model. Because there was no statistically significant improvement in fit from a 2 to a 3 profile model, we used a 2 profile model for our BMSMO sample. For BMSMW, there were significant improvements in fit from a 2 to a 3 profile model, and from a 3 to a 4 profile model. The 4 profile model included what appeared to be an outlier profile (~3% of the sample) which could not be reliably statistically analyzed. There was also no improvement in entropy from a 3 to a 4 profile model. Thus, we used the 3 profile model. Using our 2 profiles for BMSMO, and our 3 profiles for BMSMW, we created a single 5 profile variable for all subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Comparison of latent profile class models for Black men who have sex with men only and Black men who have sex with men and women (n=799).

| BMSMO (n=414) | BMSMW (n=385) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of profiles1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Bayesian Information Criterion | 19891.8 | 19816.8 | - | - | 18705.8 | 18633.7 | 18231.0 | 19066.3 |

| Log-likelihood | 9635.5 | 9598.9 | - | - | 9045.6 | 8970.8 | 8730.6 | 9109.5 |

| Entropy | 0.99 | 0.99 | - | - | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

BMSMO = Black men who have sex with men only, BMSMW = Black men who have sex with men and women. Bolding indicates significant results using the Vu-Lo-Mendel-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test comparing the 3 profile model to the 2 profile model among BMSMW (p=.009) and comparing the 4 profile model to the 3 profile model among BMSMW (p=.002).

Models with greater than 3 profiles could not be fitted for BMSMO. Models with greater than 5 classes did not result in any significant improvement in fit for BMSMW.

Latent Profile Characteristics

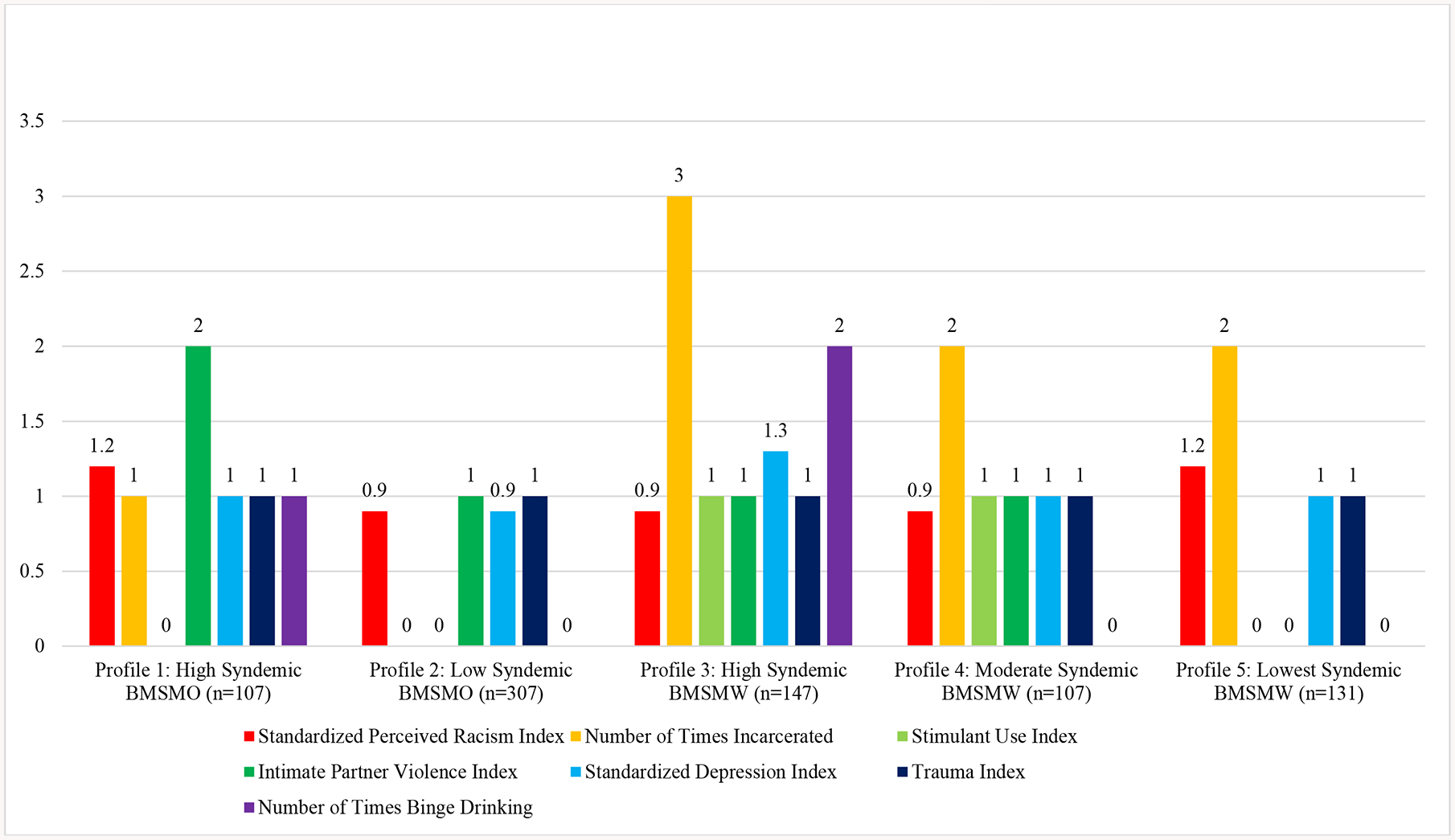

We observed differences in nearly every syndemic factor across syndemic profiles (Table 3, Figure 2). Profile 1 was characterized by the highest sexual risk and overall highest number of syndemic factors among BMSMO, including perceived racism, incarceration, IPV, depression, and binge drinking. Profile 2 was characterized by low syndemic factors and low sexual risk among BMSMO. Profile 3 reflected the highest sexual risk and highest syndemic BMSMW, with the highest number of times incarcerated, depression, and binge drinking. Profile 4 had low sexual risk behavior, but some moderately high syndemic factors, while Profile 5 had the lowest syndemic factors among BMSMW, with the exception of higher perceived racism. Based on the relative frequency of syndemic factors, we named the profiles “High Syndemic BMSMO” (n=107), “Low Syndemic BMSMO” (n=307), “Highest Syndemic BMSMW” (n=147), “Moderate Syndemic BMSMW” (n=107), and “Low Syndemic BMSMW” (n=131). In our sensitivity analyses, in both the unrestricted LPA and LPA restricted to full follow-up, we came to solutions consisting of 3 BMSMW profiles and 2 BMSMO profiles with very similar characteristics in syndemic factors. Additionally, sexual risk behaviors and STI incidence differed across syndemic profiles (Table 3, Figure 3). Overall, the highest sexual risk behaviors were observed among the Highest Syndemic BMSMW, followed by the High Syndemic BMSMO. The exception was a high number of sexual partners, which was frequent across all profiles other than the Moderate Syndemic BMSMW. Across profiles, BMSMO had substantially higher STI incidence than BMSMW.

Table 3.

Median baseline syndemic factors, 6 month sexual risk behaviors, and 12 month STI incidence among Black men who have sex with men (n=799).

| Profile 1: High Syndemic BMSMO (n=107) | Profile 2: Low Syndemic BMSMO (n=307) | Profile 3: Highest Syndemic BMSMW (n=147) | Profile 4: Moderate Syndemic BMSMW (n=107) | Profile 5: Low Syndemic BMSMW (n=131) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Standardized Perceived Racism Index1 | 1.16 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 1.16 | <.001 |

| Median Number of Times Incarcerated1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | <.001 |

| Median Stimulant Use Index1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | <.001 |

| Median Intimate Partner Violence Index1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | <.001 |

| Median Standardized Depression Index1 | 1.0 | 0.86 | 1.29 | 1.0 | 1.0 | <.001 |

| Median Trauma Index1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .414 |

| Median Number of Times Binge Drinking1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | <.001 |

| Drunk at last intercourse2 | 99.07 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <.001 |

| Drug use at last intercourse2 | 49.53 | 9.45 | 77.55 | 5.61 | 15.27 | <.001 |

| Any transactional sex2 | 17.76 | 3.91 | 36.73 | 3.74 | 12.98 | <.001 |

| Any condomless receptive anal intercourse2 | 40.19 | 35.50 | 24.49 | 8.41 | 16.79 | .004 |

| Three or more sexual partners2 | 54.21 | 42.67 | 78.23 | 0.00 | 100.00 | <.001 |

| STI3 | 11.21 | 14.01 | 4.76 | 3.74 | 1.53 | .009 |

BMSMO = Black men who have sex with men only, BMSMW = Black men who have sex with men and women.

Tested using Kruskall-Wallis test.

Tested using Chi-square test.

Tested using Chi-square test with Yates correction.

Figure 2.

Median Syndemic Factors across Latent Profiles among Black men who have sex with men (n=799).

BMSMO = Black men who have sex with men only, BMSMW = Black men who have sex with men and women. Latent profiles were associated with perceived racism (p<0.001), number of times incarcerated (p<0.001), stimulant use (p<0.001), intimate partner violence (p<0.001), depression (p<0.001), and binge drinking (p<0.001) using Kruskal-Wallis test.

Figure 3.

Number of participants engaged in 6 month Sexual Risk Behaviors and with 12 month STI across Latent Profiles among Black men who have sex with men (n=799)

BMSMO = Black men who have sex with men only, BMSMW = Black men who have sex with men and women. Latent profiles were associated with being drunk at last intercourse (p<0.001), using drugs at last intercourse (p<0.001), transactional sex (p<0.001), condomless receptive anal intercourse (p=0.004), and having three or more sexual partners (p<0.001) using Chi square test, and with incident STI using Chi-Square test with Yates correction (p=0.009).

Regression Analyses

Table 4 shows risk ratios of incident STI across profiles and mediation results, with Profile 5 (the low syndemic factor BMSMW profile) used as the reference group. Profiles 1 and 2 had substantially higher STI risk in both unadjusted and adjusted models, with nearly 3 times the risk of STI in both models compared to Profile 5. Profile 3, the Highest Syndemic BMSMW had significantly higher STI risk in unadjusted models, though this was heavily attenuated after adjusting for confounders. Nearly 15% of the increased risk of incident STI in profile 1 was significantly mediated through sexual risk behaviors, while nearly 20% of the increased risk of incident STI in profile 2 was significantly mediated through sexual risk behaviors.

Table 4.

Risk ratios of 12 month incident STI among Black men who have sex with men (n=799).

| Model 1 | Model 2 (Adjusted for Age, Site, Education, Income) | Model 3 (Adjusted for Age, Site, Education, Income, Sexual Risk Factors1) | Total Estimate (β) | Direct Estimate (β) | Indirect Estimate (β) | Percent Mediated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile 1 (High Syndemic BMSMO, n=107) | 7.35 (1.77, 30.42) | 2.60 (1.45, 4.66) | 2.27 (0.95, 5.46) | 0.956 (0.373, 1.539) | 0.821 (−0.055, 1.698) | 0.135 (0.021, 0.223) | 14.1% |

| Profile 2 (Low Syndemic BMSMO, n=307) | 9.17 (2.85, 29.55) | 2.90 (1.09, 7.66) | 2.36 (0.86, 6.51) | 1.063 (0.090, 2.036) | 0.859 (−0.156, 1.874) | 0.204 (0.053, 0.362) | 19.2% |

| Profile 3 (High Syndemic BMSMW, n=147) | 3.12 (1.01, 9.65) | 1.09 (0.31, 3.80) | 1.15 (0.29, 4.48) | 0.083 (−1.168, 1.334) | 0.138 (−1.223, 1.499) | −0.055 (−0.127, 0.0895) | −66.2% |

| Profile 4 (Moderate Syndemic BMSMW, n=107) | 2.45 (0.75, 7.99) | 0.42 (0.13, 1.34) | 0.36 (0.11, 1.21) | −0.866 (−2.022, 0.289) | −1.025 (−2.239, 0.189) | 0.159 (−0.096, 0.218) | −18.3% |

| Profile 5 (Lowest Syndemic BMSMW, n=131) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

BMSMO = Black men who have sex with men only, BMSMW = Black men who have sex with men and women.

Sexual risk factors include drinking at last intercourse, substance use at last intercourse, any transactional sex, condomless receptive anal intercourse, and having three or more partners.

Discussion

Confirming our hypotheses, the current analysis highlighted different syndemic profiles for BMSMO and BMSMW. For BMSMW with a high sexual risk profile, the syndemic factors that characterized this group were incarceration, depression, and binge drinking. These findings indicate that interventions tailored to the specific syndemic conditions characterizing high sexual risk profiles should be considered. For example, for both groups of men, mental health interventions to impact depression and binge drinking should be considered, as should policy around policing and incarceration. Whereas, for BMSMO, partner violence and interventions to reduce IPV may be particularly important.

Additionally, our analysis showed that across all 5 profiles, BMSMO had substantially higher STI incidence compared to BMSMW. Both high and low risk profile BMSMO had 3 times the risk of STI compared to low risk low syndemic BMSMW, which was explained by high risk sexual behaviors. This suggests that STI risk reduction interventions should address sex while under the influence of, as well as providing support for men who may be involved in exchange sex, that might result from incarceration and poorly resourced reentry programs.

Additionally, sexual risk behaviors and STI incidence differed across syndemic profiles and overall, the highest sexual risk behaviors were observed among the Highest Syndemic BMSMW, followed by the High Syndemic BMSMO. These findings align with prior studies that highlight syndemic differences between BMSMO and BMSMW, with BMSMW being significantly more likely to report polydrug use, depression symptoms, IPV, physical assault, sexuality nondisclosure, and lack of gay community support.7,77 BMSMW already suffer from biphobia (i.e. stigmatization and marginalization from both gay and heterosexual communities), which in addition to incarceration, further marginalizes them from society, which may increase sexual risk taking and subsequent STI.11,77

There are limitations to be acknowledged. First, the study was limited to 6 urban US cities, which decreases generalizability to BMSM in other geographic regions. Second, a high HIV risk sample was enrolled which also limits generalizability. Third, self-report may contribute to social desirability bias which may have been minimized by using ACASI. In addition, the possibility of spurious associations due to misclassification as a result of other forms of bias (e.g. recall) cannot be ruled out. Despite these limitations, our focus on BMSM is warranted given the additional relevance of adverse health outcomes in this population, including disproportionately high STI rates compared to MSM of other racial/ethnic groups. Social desirability bias is likely to affect our measures, particularly those related to experienced racism and discrimination. Finally, our use of the classify-analyze approach does have limitations, as it does not fully account for the uncertainty in profile probabilities and is known to attenuate estimates. However, we were able to detect significant associations between syndemic profiles and both sexual risk behaviors and STI outcomes.

The findings have strong implications for research given our focus on delineating the differential syndemic profiles between BMSMW and BMSMO, normally presented as a homogeneous group. The longitudinal nature of the current analysis also allowed the assessment of temporal relationships and mediation.

These finding align with several studies that utilize a syndemic framework to assess sexual risk, and HIV/STI incidence.51,78–80 These findings are useful in developing interventions for STI risk reduction, tailored to unique experiences of both subgroups of BMSM, to minimize sexual risk taking and resulting STI. Factors such as sexual network structure and STI within networks, themselves may play a role in incident STI and should be considered in future research.

Social and legal policy informed by a nuanced understanding of patterns of these syndemic factors for both groups of men and their relationship with sex risk and STI, particularly discrimination and incarceration is necessary to promote health for all BMSM.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The authors would like to thank the HPTN Scholar’s Program; HPTN 061 Study Participants; HPTN 061 Protocol Co-Chairs: Beryl Koblin, PhD, Kenneth Mayer, MD, and Darrell Wheeler, PhD, MPH; HPTN 061 Protocol Team Members; HPTN Black Caucus; HPTN Network Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; HPTN CORE Operating Center; FHI360; Black Gay Research Group; Clinical Research Sites, Staff, and CABs at Emory University, Fenway Institute, GWU School of Public Health and Health Services, Harlem Prevention Center, New York Blood Center, San Francisco Department of Public Health; UCLA. The Agents of Change (AOC) Writing Group at the University of Maryland, School of Public Health, and the Center for Health Equity for their continued support.

HPTN 061 grant support provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Cooperative Agreements UM1 AI068619, UM1 AI068617, and UM1 AI068613, as well as Syndemics, HIV and STI among Black Men who have Sex with men and Women (R03 DA- 037131), Stop-and-Frisk, Arrest, and Incarceration and STI/HIV Risk in Minority MSM (R01 DA- 044037), Project DISRUPT (R01 DA-028766).

Footnotes

The authors acknowledge there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2016. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su JR, Beltrami JF, Zaidi AA, et al. Primary and secondary syphilis among black and Hispanic men who have sex with men: case report data from 27 states. Ann of Intern Med. 2011;155(3):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyer TP, Regan R, Wilton L, et al. Differences in substance use, psychosocial characteristics and HIV-related sexual risk behavior between Black men who have sex with men only (BMSMO) and Black men who have sex with men and women (BMSMW) in six US cities. J Urban Health. 2013;90(6):1181–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyer TV, Khan MR, Regan R, et al. Differential Patterns of Risk and Vulnerability Suggest the Need for Novel Prevention Strategies for Black Bisexual Men in the HPTN 061 Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(5):491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maulsby C, Sifakis F, German D, et al. HIV risk among men who have sex with men only (MSMO) and men who have sex with men and women (MSMW) in Baltimore. J homosex. 2013; 60(1):51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman MR, Bukowski L, Eaton LA, et al. Psychosocial health disparities among black bisexual men in the US: effects of sexuality nondisclosure and gay community support. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(1):213–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harawa NT, McCuller WJ, Chavers C, et al. HIV risk behaviors among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latina female partners of men who have sex with men and women. AIDS Beh. 2013;17(3):848–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyer TP, Regan R, Pacek LR, et al. Psychosocial vulnerability and HIV-related sexual risk among men who have sex with men and women in the United States. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):429–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, et al. The high prevalence of incarceration history among Black men who have sex with men in the United States: associations and implications. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, et al. Exploring the relationship between incarceration and HIV among Black men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014. 65(2):218–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman MR, Dodge BM. The role of syndemic in explaining health disparities among bisexual men: A blueprint for a theoretically informed perspective In: Understanding the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States. Springer; 2016:71–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singer M A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inq Creat Sociol. 2000;28(1):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyer TP, Shoptaw S, Guadamuz TE, et al. Application of syndemic theory to black men who have sex with men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Urban Health. 2012;89(4):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrick AL, Lim SH, Plankey MW, et al. Adversity and syndemic production among men participating in the multicenter AIDS cohort study: a life-course approach. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright ER, Carnes N. Understanding the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States: The Role of Syndemics in the Production of Health Disparities. Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman MR, Stall R, Plankey M, et al. Effects of syndemics on HIV viral load and medication adherence in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(9):1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halkitis PN, Singer SN. Chemsex and mental health as part of syndemic in gay and bisexual men. I J Drug Policy. 2018;55:180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyer TP, Shoptaw S, Guadamuz TE, et al. Application of Syndemic Theory to Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Urban Health. 2012;89(4):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Baker JJ, Korostyshevskiy VR, et al. The Association of Intimate Partner Violence, Recreational Drug Use with HIV Seroprevalence among MSM. AIDS Beh. 2012:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterson JL, Jones KT. HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6): 976–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siemieniuk R, Miller P, Woodman K, et al. Prevalence, clinical associations, and impact of intimate partner violence among HIV-infected gay and bisexual men: a population-based study. HIV Med. 2013;14(5): 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler DP, Hadden BR, Lewis M, et al. HIV testing and Black and African American communities in the twent-first century. Handbook of HIV and Social Work: Principles, Practice, and Populations. 2010:271. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malebranche DJ, Gvetadze R, Millett GA, et al. The relationship between gender role conflict and condom use among black MSM. AIDS Beh. 2012; 16(7):2051–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingham TA, Harawa NT, Williams JK. Gender Role Conflict Among African American Men Who Have Sex With Men and Women: Associations With Mental Health and Sexual Risk and Disclosure Behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffries WL, Marks G, Lauby J, et al. Homophobia is Associated with Sexual Behavior that Increases Risk of Acquiring and Transmitting HIV Infection Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Beh. 2012; 17(4):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, et al. Perceived Discrimination and Physical Health Among HIV-Positive Black and Latino Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Beh. 2013; 17(4):1431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham LF, Aronson RE, Nichols T, et al. Factors Influencing Depression and Anxiety among Black Sexual Minority Men. Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, et al. Clinically significant depressive symptoms as a risk factor for HIV infection among black MSM in Massachusetts. AIDS Beh. 2009;13(4):798–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Safren SA, Heimberg RG. Depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and related factors in sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safren SA, Reisner SL, Herrick A, et al. Mental health and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.