Abstract

Folliculogenesis is a complex process that requires integration of autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine factors together with tightly regulated interactions between granulosa cells and oocytes for the growth and survival of healthy follicles. Culture of ovarian follicles is a powerful approach for investigating folliculogenesis and oogenesis in a tightly controlled environment. This method has not only enabled unprecedented insight into the fundamental biology of follicle development but also has far-reaching translational applications, including in fertility preservation for women whose ovarian follicles may be damaged by disease or its treatment or in wildlife conservation. Two- and three-dimensional follicle culture systems have been developed and are rapidly evolving. It is clear from a review of the literature on isolated follicle culture methods published over the past two decades (1980–2018) that protocols vary with respect to species examined, follicle isolation methods, culture techniques, culture media and nutrient and hormone supplementation, and experimental endpoints. Here we review the heterogeneity among these major variables of follicle culture protocols.

Keywords: follicle culture, follicle, follicular development, oocyte

Follicle culture is a widespread technique used in reproductive biology, and significant heterogeneity exists in protocols, including species examined, isolation methods, culture techniques, media and hormone supplementation, and experimental end points.

Introduction

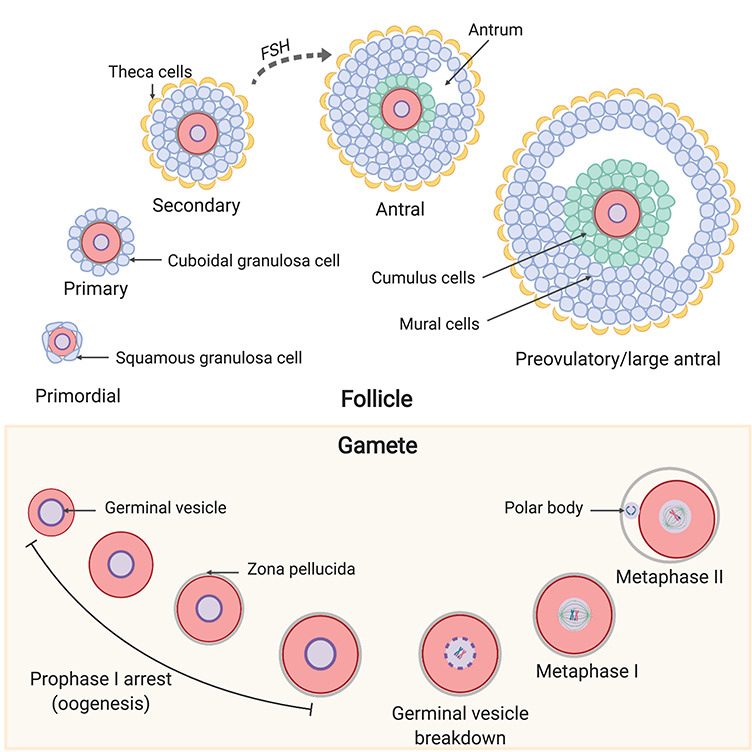

The ovary produces steroid hormones, estrogen and progesterone, and fertilization-competent oocytes. The follicle is the functional unit of the ovary, composed of an oocyte surrounded by granulosa cells and theca cells [1]. Folliculogenesis begins when primordial follicles activate and transition into primary follicles. This transition is marked by oocyte growth and conversion of squamous granulosa cells into cuboidal ones. As the follicle grows, a basement membrane surrounds the follicle and the oocyte secretes a glycoprotein matrix, the zona pellucida, which separates it from granulosa cells. With continued granulosa cell proliferation and oocyte growth, the follicle becomes a secondary follicle, at which point androgen-producing theca cells differentiate outside the basement membrane, and the follicles become gonadotropin dependent. The transition to the antral follicle stages occurs when a cavity filled with follicular fluid develops. Depending on the species, either a single (mono-ovulatory) or multiple follicles (poly-ovulatory) complete folliculogenesis and undergo ovulation, whereas the remaining follicles that entered the growing pool in that cycle undergo atresia (Figure 1) [2, 3].

Figure 1.

Key stages of follicle and oocyte development that must be recapitulated in vitro. During follicular development, primordial follicles are activated, and their surrounding squamous granulosa cells change to a cuboidal shape, making them primary follicles. Primary follicles grow to secondary follicles with a theca layer. Secondary follicles are gonadotropin dependent and can respond to FSH to grow into larger antral follicles and then preovulatory follicles. At the antral and preovulatory stage, the oocyte is surrounded by cumulus and mural granulosa cells. During oogenesis, immature oocytes with a germinal vesicle remain in prophase I arrest within the ovary. Oocytes resume meiosis at the time of ovulation and ultimately reach metaphase of meiosis II at which point they are called an egg and can be fertilized in the presence of sperm.

Folliculogenesis and oogenesis are essential for sustained reproductive function and fertility and are under complex genetic, paracrine, autocrine, and juxtracrine control to regulate follicle formation, activation, and growth [2–5]. Being able to recapitulate these processes in vitro provides a tightly controlled system in which to interrogate this fundamental biology, and numerous follicle culture systems have been developed. This method also has important clinical implications for the preservation of reproductive potential in endangered species or in women facing iatrogenic infertility due to cancer treatment (e.g., chemotherapy and radiation therapy) [6, 7]. Moreover, it can be used as an in vitro toxicity assay to predict adverse reproductive outcomes of drugs and chemicals [8, 9].

To recapitulate the unique microenvironment of the ovarian follicle and its complex cell–cell interactions, a wide range of culture techniques now exist. Here we comprehensively review key practices and variables in follicle culture protocols, including species differences, animal age, isolation methods, two-dimensional (2D) versus three-dimensional (3D) systems, media use in culture, hormone supplementation (with a focus on follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH]), and culture endpoints. Eighty-six articles published between 1980 and 2018 were identified based on a PubMed search using the terms: “in vitro follicle,” “follicle culture,” “follicle culture systems,” “follicle growth,” “alginate,” and “alginate encapsulation.” Only papers that studied isolated ovarian follicle culture were included. In situ culture of preantral ovarian follicles within ovarian tissue has been studied extensively and is successful in a variety of animal models such as caprine [10], equine [11–16], and wild felids [17]. However, these studies are beyond the scope of the current review. This review does not include every single publication on follicle culture; rather it represents a robust sampling of the field.

Follicle culture systems have been established in multiple species

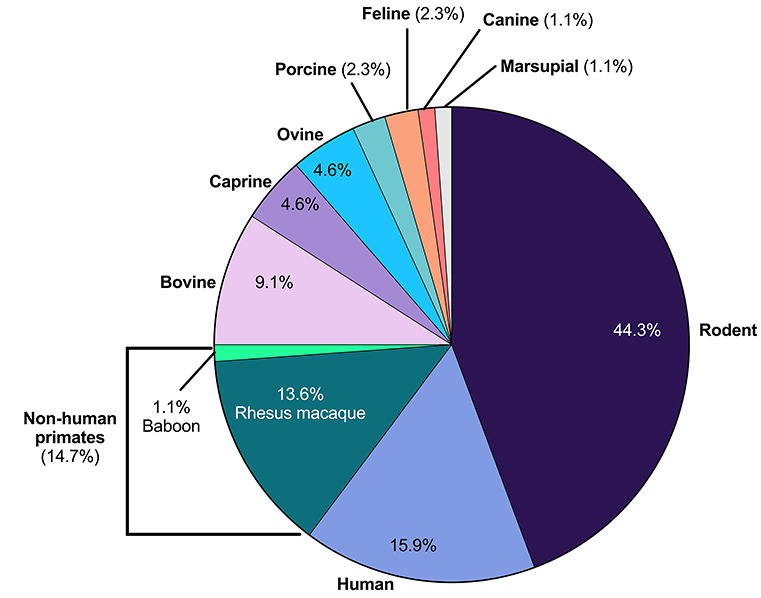

Given its broad applications, it is not surprising that follicle culture has been established in various species (Figure 2). Follicle sizes [18] and rates of oocyte development vary across species [19], so a standardized classification of follicle stage does not exist. The nomenclature established by the Pedersen and Peters [20] or Hirshfield [21] is commonly used to categorize murine follicles. Several classification systems are based on follicle diameters or use broad terminology such as “preantral follicles” to describe follicles ranging from the primordial to multilayer secondary stage. For the purposes of this review, we define preantral granulosa–oocyte cell complexes (PGOC) as larger multilayered follicles without a basement membrane, and cumulus–oocyte complexes (COC) as oocytes surrounded by specialized granulosa cells known as cumulus cells, which can be obtained from antral follicles. It is important to note that size differences exist between in vitro and in vivo grown follicles, with those grown in vitro reaching much smaller terminal diameters compared with in vivo [22–24].

Figure 2.

Distribution of species used in follicle culture studies examined. In studies that used more than one species, each species reported per study was accounted for in this analysis. Rodent studies are predominant, comprising 44.3% of the studies examined, followed, by humans at 15.9% and non-human primates at 14.7%. Agricultural species such as bovine (9.1%), caprine (4.6%), ovine (4.6%), and porcine (2.3%) are also used widely in follicle culture studies. Lesser used species are feline (2.3%), canine (1.1%), and marsupial (1.1%).

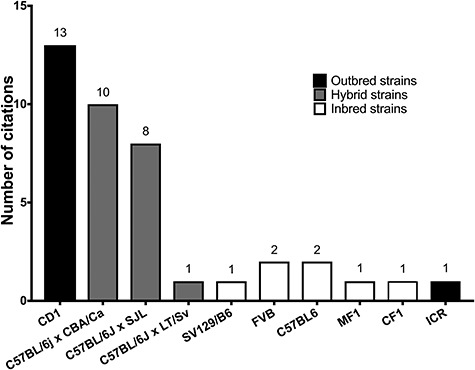

Rodent models, including mouse and rat, are a common reproductive biology model system, and follicle culture in this species accounted for 44.3% of the studies examined (Figure 2). Within the Rattus norvegicus domestica species (laboratory rat), follicle culture studies examined in this review specifically used Sprague Dawley rats [25, 26]. Within the Mus musculus species, follicle culture has been performed in outbred [27–30], inbred [31–35], and hybrid strains (Figure 3) [36–38]. Outbred strains are “a closed population (for at least four generations) of genetically variable animals that is bred to maintain maximum heterozygosity” [39]. Inbred strains have undergone at least 20 generations of brother–sister or offspring–parent interbreeding, leading to at least 98.6% homozygous loci in an individual, such that each individual is effectively a clone [40]. F1 hybrid mice originate from mating two different inbred strains [41]. After rodents, primates were the most frequent model system, with 15.9% studies done with human follicles [22, 42–45] and 14.7% studies in non-human primate follicles, including rhesus macaque [23, 24, 46–56] and baboon [57] (Figure 2). Follicle culture methods have also been performed in bovine [58–66], ovine [67–70], caprine [63, 71–73], and porcine [74, 75] models, which together comprise 20.6% of the studies. Cat [76, 77], dog [78], and marsupial [79] follicles were also used. Beyond our selected references, follicle culture has been performed in additional species, including hamster [80], horses [11], wild felids [17], and others, demonstrating the wide range of species diversity used in follicle culture.

Figure 3.

Strains of mouse used in follicle culture studies examined. Outbred strains such as CD1 were the most popular, followed by various F1 hybrid mice. Inbred strains such as FVB were used less often.

Follicle culture outcomes vary by species

Live births from gametes derived from follicle culture have only occurred in the mouse [38]. However, successful preimplantation development has occurred following fertilization of eggs obtained from follicles cultured in rat [81], pig [75], buffalo [82], sheep [70], goat [73], and rhesus macaque [49]. Cumulus expansion and in vitro oocyte maturation (IVM) have been achieved from follicle culture in both rhesus macaque [46] and baboon [57]. In human studies, only meiotically competent metaphase II (MII)-arrested oocytes have been obtained [22, 83], because legal and ethical restrictions prohibit human egg activation and fertilization [6, 84–86]. Thus, it is not possible to assess the quality of gametes derived from cultured human follicles.

Differences in follicle culture outcomes are likely due to inherent differences between species. For example, in large mammalian species, follicle diameters beyond the preantral stage are much larger relative to those in rodents. Mature murine follicles at the preovulatory stage measure only up to 420 μm in diameter, compared with 600 μm in ovine, 750 μm in caprine, 800 μm in porcine, and 20 000–23 000 μm in diameter in bovine and human, respectively [87]. Moreover, the duration of folliculogenesis and oocyte maturation differ between species. For example, in the mouse, it takes approximately 17–19 days for a follicle to reach its maximal diameter [88], whereas in large mammalian species it takes several months [89]. Thus, in large mammalian species, there are significant challenges to maintain nutrient supply, gas exchange, and hormone and growth factor needs over extended culture periods [3, 90]. Structural differences in follicle architecture between species may also influence outcomes. For example, the thick theca layer in follicles from large domestic animals can restrict nutrient supply and gas exchange [67]. Therefore, the outcomes of many follicle culture studies have been limited to or tailored to the specific species used.

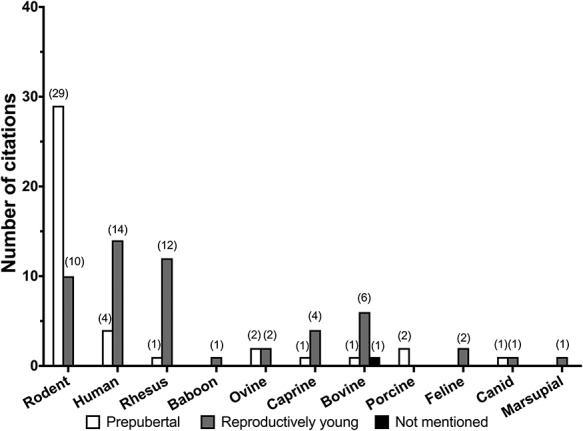

Follicles used for culture are obtained from animals at different ages and cycle stages

Within a given species, animals used for follicle culture studies were prepubertal (immature), of young reproductive age (adult and cycling), or age was not specified (Figure 4). Due to the age-associated decline in follicle quantity, we did not come across follicle culture studies in animals of advanced reproductive age that were not cycling or in menopausal women. In rodents, 74.4% of studies used follicles from prepubertal animals (<27 days) and 25.6% used reproductively mature ones (>27 days). Prepubertal mice were used either as gonadotropin-independent models [91] or because a high yield of a relatively homogenous population of primary and secondary follicles can be isolated at this age [92, 93]. Adult mice were most commonly used for PGOC [36, 94, 95] and antral follicle [32, 96] culture. Prepubertal and adult mice were used in parallel to explicitly study age-dependent variation in follicle culture outcomes [97]. There is a clear estrous cycle dependence because follicles from animals in diestrus produce less steroid hormone and have compromised oocyte quality compared with other estrous cycles stages [97].

Figure 4.

Distribution of the age of species used in follicle culture studies examined. Age was classified into three broad categories: prepubertal, reproductively young, and other (when age is not mentioned). If a citation mentioned the use of multiple age groups for follicle culture, each age group was counted independently.

The majority of ovine [68, 70], caprine [71–73], and bovine [61, 62, 64, 65] follicle culture studies were performed using reproductively young animals. These studies could not directly investigate the effect of estrous cycle on follicle culture outcome because ovaries were obtained from slaughterhouses. Some studies have used follicles from prepubertal or younger animals; fetal bovine ovaries are softer than adult ovarian tissue, thereby allowing easier removal of the cortex [98]. Prepubertal bovine and ovine animals have been used to study smaller follicles (primordial and primary), especially in studies using FSH supplementation [59, 67, 69]. Prepubertal caprine follicles were used in a single study comparing the growth of cultured follicles from young and adult goats in a 2D or 3D culture system [72]. Prepubertal pigs were used to investigate whether smaller preantral follicles can be grown in vitro to antral follicles [74, 75]. Follicles from both prepubertal and reproductively young adult animals have been used in follicle culture studies in dogs in various estrous stages [78] and adult marsupials (estrous stage unknown) [79].

Among nonhuman primates, rhesus macaque follicles were predominantly from reproductively young animals (>4 years of age in 12 studies) [23, 24, 46–56], whereas only one study compared reproductively young animals with prepubertal animals (1–3 years of age) [47]. Small antral follicles isolated during the early follicular phase in rhesus monkeys resulted in the highest yield of healthy oocytes and highest ratio of healthy to degenerating oocytes compared with any other menstrual cycle stage [46]. In one study, small antral follicles from adult baboons in the luteal phase were cultured and produced gametes that underwent meiosis and produced viable embryos [57].

In the human studies, tissues were donated following informed consent by patients undergoing surgical interventions for clinical complications [44, 99], elective Cesarean section [43, 100], fertility preservation [22, 28, 45, 101, 102], and other gynecological procedures [42, 103, 104]. In each study, follicles were obtained from premenopausal donors, either prepubertal (younger than 12 years of age) or reproductively adult (12–49 years of age) [28, 42–45, 99–104] without any documentation of menstrual stages.

The wide range of species, ages, and cycle stages used in follicle culture studies underscore that these factors are selected based on the specific study objectives and outcomes, and in some cases, ease of access to ovarian tissue. When evaluating other protocol variables in follicle culture systems, such as isolation techniques, initial follicle sizes, study strategies, and hormone usage, it is important to consider the impact of the species used, the animal’s reproductive age, and cycle stage.

Follicle isolation methods for culture vary across studies and are dependent on follicle stage

The first step of follicle culture is isolating follicles from the ovarian tissue. Follicles must be morphologically intact to support follicular development [105]. Ovarian follicle isolation techniques (Supplementary Table S1) can be broadly classified as enzymatic, mechanical, or a combination of both. Enzymatic isolation of follicles has been described for multiple species (Supplementary Table S1) and typically involves use of collagenases and/or Liberase to proteolytically digest the extracellular matrix (ECM). Protocols vary regarding enzyme concentration and treatment temperature and duration. Enzymatic digestion generally yields a larger number of follicles and is less time consuming and laborious, especially in fibrous tissue of most domestic animals, compared with mechanical isolation [105, 106]. However, there is a greater risk of follicle damage with enzymatic digestion. Collagenase treatment of mouse ovaries usually results in PGOCs and COCs rather than whole follicles due to degradation of theca cells and the basement membrane [107]. Fetal calf serum (FCS) has shown to mitigate these effects [108].

Mechanical isolation involves the microdissection of individual follicles from the surrounding ovarian stroma using insulin needles or watchmaker’s forceps (Supplementary Table S1) [29, 32, 33, 96, 109–114]. Tissue choppers, homogenizers, and cell dissociation sieves [76, 106] have alternatively been used to mechanically isolate follicles from the stroma. Mechanical isolation better maintains the theca layer and physiologic follicular morphology compared with enzymatic isolation [105, 106]. However, microdissection is time consuming [105]. Taken together, the means of follicle isolation is largely dependent upon the follicle stage of interest and species of animal used in the study. In many cases, a combination of brief enzymatic digestion followed by mechanical isolation may be most effective to obtain the maximum number of follicles required for the study without sacrificing the integrity of follicle structure (Supplementary Table S1).

2D culture systems are preferred for short-term cultures

For this review, we have categorized follicle culture systems as 2D or 3D (Figure 5). In 2D systems, follicles are attached to a surface, whereas in 3D systems, follicles are encapsulated within a biomaterial [3]. The various 2D systems are summarized in Supplementary Table S2 and include the droplet method, the substrate method (with and without ECM coating), and membrane insert systems. Overall, 2D culture systems have been more successful for culturing follicles from smaller animals and for assessing short-term outcomes such as hormone measurement and gene expression. Evaluation of folliculogenesis and oocyte maturation outcomes is somewhat limited in 2D systems, because the granulosa cells migrate on the culture surface away from the oocyte as they proliferate [2, 115] (Figure 1). Loss of cell–cell communication within the follicle leads to arrested follicle growth, ovulation suppression, and impaired oocyte meiotic competence [2, 3]. Because follicles can only be sustained in culture for a limited time using 2D systems, generally later stage follicles are used in these systems, and the culture duration in these systems are shorter relative to 3D systems.

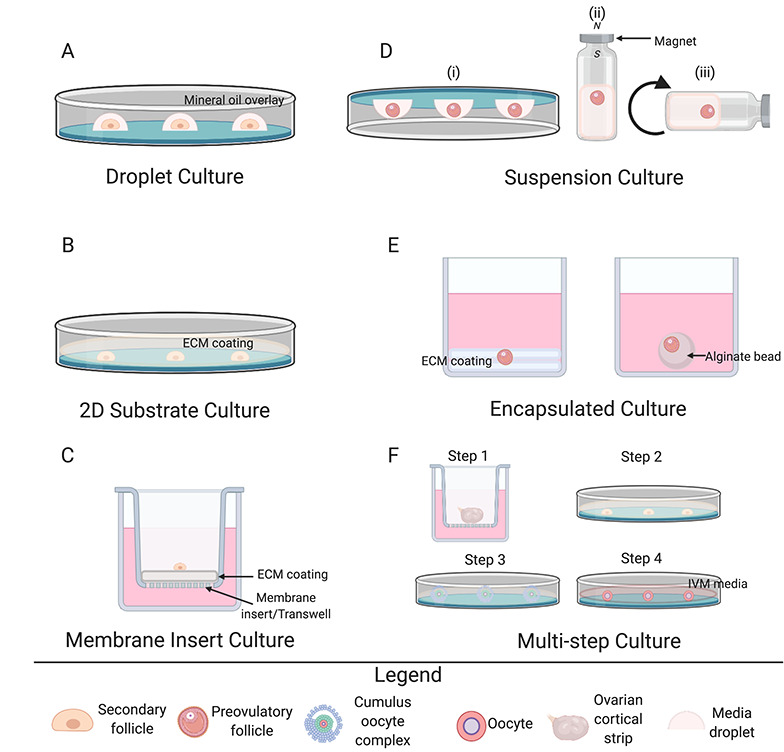

Figure 5.

Schematic overview of 2D and 3D culture systems. (A–C) 2D culture methods include droplet cultures (A), 2D substrate cultures with and without ECM coating (B), and membrane insert cultures with and without ECM coating (C). (D–F) 3D culture methods include suspension cultures (D) such as inverted droplet (i), magnetic levitation (ii), and roller culture (iii); encapsulated culture (E) between coatings of (i) ECM or(ii) alginate drops; and multistep culture (F). The multistep culture of McLaughlin et al. [83] is pictured as a representative technique. Cortical strips were first cultured in medium for 8 days (step 1). Intact follicles were dissected and cultured individually for an additional 8 days (step 2), and then COCs with mural and cumulus cells were isolated from the follicles and cultured on membranes for 4 more days (step 3). COCs with oocytes greater than 100 μm were selected for IVM (step 4).

Droplet culture systems

In the droplet method, individual follicles are seeded in a drop of culture media in a dish, which is often overlaid with mineral or paraffin oil. The droplet method has been used with follicles at various stages as well as COCs from multiple species, including mouse [27, 31, 116, 117], rhesus macaque [49], sheep [67, 70], marsupial [79], goat [63, 71–73], and cattle [63, 64]. Viable embryos have been obtained from this technique in sheep [70] and goat [73]. The average duration of culture with the droplet method is approximately 6 days [27, 67, 70, 79], although some caprine and bovine studies have sustained cultures for 18 [63, 71, 73] and 32 days [64].

2D substrate systems

Follicles have been cultured either directly on the surface of a culture dish or well or on surfaces coated with ECM components such as collagen, laminin, or Matrigel (a commercially available gelatinous protein mixture secreted from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma cells) [2]. The follicles are then covered with culture medium. The ECM has important roles in vivo in the ovary in regulating cell behavior, differentiation, and secretory activity, so incorporating ECM components into follicle culture provides important cues for folliculogenesis [115, 118, 119]. Specifically, proteins such as collagen are flexible and have elastic properties that facilitate intercellular communication, whereas Matrigel promotes cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation [120].

Larger size follicles such as preantral and antral follicles [29, 32, 33, 51, 56, 61, 65, 68, 75, 96, 109–114], COCs [46, 95], and PGOCs [36, 94] have been used in 2D plastic substrate systems. Due to their large terminal diameters, follicles from larger mammals require longer culture durations. By starting cultures with larger follicles, the time in culture could be reduced to improve outcomes, even in a 2D system that will inevitably disrupt follicle architecture [2, 3, 106]. The duration of culture with this method ranges from a few hours to several days and has been more successful in smaller animals such as the mouse [3]. An exception was a study in the porcine model wherein a 3-day culture in a 2D substrate system produced oocytes that were fertilized by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [75]. Only one study used a fibronectin-coated plastic dish to culture ovine primordial and primary follicles; follicle development and oocyte diameter were not improved significantly compared with follicles cultured in an uncoated plastic dish under the same conditions [69]. In the few examples of longer 2D cultures, studies have used follicles from larger mammalian species such as rhesus macaque (5 weeks) [56] and cow (28 [61] and 32 days [65]).

Membrane insert systems

Membrane insert systems, with or without ECM protein coating, operate on a similar principle as 2D plastic substrate systems, but follicles are seeded onto an insert within a well of a culture plate and immersed in media. Follicle culture using the membrane insert system has led to improved follicle growth and ovulation in murine follicles [27]. Mechanically isolated human follicles were cultured for the first time in vitro using the membrane insert system for up to 4 weeks [42] and other studies have used membrane inserts coated with ECM proteins such as collagen to culture COCs [91, 121]. Other 2D follicle culture systems include use of glass coverslips coated with various ECM components such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen, but this method was inferior to a 3D system that maintained follicle architecture [34].

2D systems constitute some of the first ovarian follicle culture techniques and protocols. Although 2D systems generally result in the breakdown of characteristic follicle architecture throughout the culture, these systems have been largely successful in shorter-term cultures and those that use more advanced stage follicles from smaller animal species. The advent of 3D systems, as described further below, represents a major advance over 2D culture systems because of their ability to maintain follicle integrity.

3D follicle culture systems mimic the in vivo environment and are useful to culture follicles for longer durations

Although 2D follicle culture has been successful, a major limitation of these systems is their inability to maintain follicle architecture, with the oocyte surrounded by granulosa cells. This is particularly problematic with follicles from large mammalian species, which require sustained association between oocytes and granulosa cells over longer-term cultures [3]. The need to maintain intact follicle architecture has led to 3D culture systems in which follicles are encapsulated in a biomaterial or their access to a substrate is limited [3]. 3D systems vary widely, with some systems encapsulating or layering follicles into various scaffolds, others using suspension culture without a substrate, or using multiple steps including in situ culture to grow follicles (Supplementary Table S3). The various matrices used to encapsulate follicles allow the somatic cells to proliferate while maintaining follicle architecture and cell–cell interactions, thereby creating a microenvironment very similar to that of the in vivo ovary [120]. Matrices have been engineered from natural components such as collagen, alginate, or Matrigel, or from synthetic components such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels cross-linked with proteolytically sensitive peptides [2].

Suspension follicle culture systems

Suspension cultures are 3D systems in which follicle morphology is maintained by various non–scaffold-based approaches, including continuous agitation in test tubes or glass bottles (roller system), inversion, or levitation with magnetic beads. In the inverted method, follicles are cultured within media in 96-well round-bottomed suspension tissue culture plates that are inverted prior to incubation. Surface tension holds the media in place, allowing the follicle to settle at the media/gas interface rather than near the plate surface [31, 79]. In the marsupial, mature oocytes have been obtained with higher efficiency using the inverted droplet compared with the upright droplet system or several other methods, including the roller system [79]. Rat follicles cultured within polypropylene test tubes placed on a circular rotator plate (to achieve a suspension culture) produced oocytes that resumed meiosis and mature eggs that could undergo parthenogenic activation and be fertilized by ICSI [26]. Bovine follicles cultured using the magnetic levitation 3D system had greater follicle viability and antrum formation and lower extrusion and degeneration rates compared with a traditional 2D system. The follicles also produced viable oocytes that resumed meiosis after IVM [66].

Encapsulated follicle culture systems

In encapsulated culture systems, the entire follicle is surrounded by a biocompatible material that maintains the 3D architecture of the follicle. Collagen and agar gels are natural, biodegradable materials that have been used for this purpose. These materials can be layered on plastic dishes, with follicles “sandwiched” between the layers. In the first reported study of 3D follicle culture using a collagen gel matrix, an absence of antrum formation was reported due to matrix rigidity despite an increase in follicular size [2]. In the studies examined in this review, collagen and agar gel matrices enabled longer cultures in murine [116, 122] and porcine [74] models compared with most 2D systems most likely due to maintained follicle architecture. Human studies using collagen and agar gels have been shorter, however, ranging from 24 to 120 h, with follicular and oocyte integrity deteriorating beyond this point [44, 103].

Alginate, a naturally derived hydrogel produced by brown algae, is widely used as a matrix for follicle culture due to its biocompatibility and high tunability [120]. Alginate is a block copolymer (a copolymer formed when the two monomers cluster together and form “blocks” of repeating units) of alpha-L-glucuronic acid (G) and beta-D-mannuronic acid (M) units. The units alternate between blocks of purely G, purely M, and either G or M monomers. In the presence of calcium, the G-blocks of alginate cross-link to form a hydrogel [3]. The first documented study utilizing alginate for culture of murine COCs showed that cell communication was maintained, granulosa cells proliferated, and oocyte volume increased [30]. The rigidity of the gel can be controlled by modifying the concentration of alginate. This is important as smaller follicles are typically found in the more rigid ovarian cortex and move toward the less rigid medulla as they grow. Modifying concentrations of the alginate to mimic the relative stiffness of the cortex or the medulla recapitulates the physical microenvironments of the ovary to support stage-specific follicle development [2]. Previous studies have demonstrated that higher and more rigid concentrations of alginate maintain the survival of murine primordial follicles, whereas lower percentages support the growth and development of activated follicles, yielding greater follicular development and antrum formation [28, 38, 123]. Follicle culture studies in the dog have further compared the effect of varying the concentrations of alginate and found that lower concentrations promoted follicular growth, whereas higher concentrations were optimal for hormone production [78]. In humans and nonhuman primates, a more rigid microenvironment is beneficial for primordial follicles and earlier stage follicles [2, 24, 45, 50, 124].

Increased follicular growth and survival outcomes were observed when smaller preantral murine follicles were encapsulated using alginate in cohorts compared with individually encapsulated follicles [125]. Murine follicles cultured in vitro in alginate also produced oocytes with a transcriptome that was approximately 99.5% similar to oocytes developed in vivo; however, the developmental competence of these oocytes was compromised [35]. Increased growth and survival of follicles was also observed when gonadotropin supplementation matched stage-specific requirements of primordial (gonadotropin-independent) versus activated follicles (gonadotropin-dependent) [119]. In nonhuman primates such as rhesus macaque, alginate encapsulation has successfully produced meiotically competent oocytes and cleavage-stage embryos [48]. In human studies, Xiao et al. [22] reported the production of the first mature MII oocytes cultured from follicles in a combination system, beginning with culture of preantral follicles in 0.5% alginate for 10–15 days and then transitioning the antral follicles into low-attachment plates for up to a 40-day culture.

In agricultural species, alginate encapsulation of follicles has proven to be a useful tool for comparing 2D and 3D follicle culture systems (bovine [64] and caprine [72]). In the bovine model, the effect of media supplementation was shown to be dependent on the culture system (2D versus 3D). For example, vascular endothelial growth factor was an effective supplement for the culture of bovine secondary follicles in 2D, whereas growth hormone (GH) affected estradiol production in the 3D alginate system [64]. In the caprine model, 3D alginate encapsulation resulted in higher rates of follicle survival, lower rates of oocyte extrusion, and a greater number of recovered oocytes for IVM and in vitro fertilization (IVF) compared with the 2D substrate system. However, follicles grown in 2D culture produced higher levels of progesterone compared with those cultured in 3D [72].

The hydrogel system has been further engineered by blending alginate with fibrin to create a dynamic interpenetrating fibrin–alginate network (IFN) [2]. Fibrin is a blood-clotting protein that is used as a surgical adhesive and as a scaffold material in tissue engineering [92]. As follicles develop within the IFN, the fibrin is degraded by follicular proteases, leaving behind a lower concentration of alginate and a less rigid environment. This transition in rigidity mimics the shift in microenvironment experienced by follicles in vivo, as smaller follicles develop and transit from the rigid outer ovarian cortex to the inner, softer ovarian medulla [126]. The IFN system has generated follicles containing oocytes with a high degree of meiotic competence in rodents [92, 127] and has increased the production of growing primary, but not secondary follicles in macaques [52].

Follicles encapsulated in alginate have also been co-cultured with other components such as stromal cells [128] and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) [129]. Ovarian stromal cells, which consist mostly of theca cells and macrophages, improved the growth, survival, and androgen production of small murine primary and secondary follicles [128]. When feeder cells such as MEFs were co-cultured with primary follicles encapsulated in alginate, growth was stimulated but survival was low [129]. Co-culture of human preantral follicles with ovarian interstitial tissue did not show any significant benefit to follicle outcomes relative to untreated controls [102].

Other matrices used in 3D follicle culture include Matrigel, which maintains 3D follicle architecture while also providing a protein-rich environment for folliculogenesis [2]. When luteal phase follicles from baboons were encapsulated in Matrigel combined with fibrin and alginate, follicles grew and produced mature oocytes [57]. Alginate has also been blended with other ECM components such as collagen, laminin, and fibronectin, and this study showed that the interaction of the ECM component and developmental stage of the follicle regulates follicle maturation [115]. Hyaluronan, a ubiquitous glycosaminoglycan, has also been used for follicle culture [120]. Hyaluronan matrices allow for optical transparency and are tunable. A hyaluronan–ECM scaffold (without alginate) was no different from a hyaluronan-only scaffold in terms of murine follicle survival, size, or meiotic competence; however, the hyaluronan–ECM scaffold supported greater steroid hormone production [130]. PEG is a synthetic matrix that behaves similarly to fibrin and degrades in response to protease secretion from a growing follicle [2]. PEG culture systems supported a 17-fold volumetric expansion of follicles during culture in a murine model [131].

Multistep culture systems

Multistep culture systems have been developed to further mimic the physiologic environment of developing follicles. These systems have been used for culturing primordial, primary, and early-secondary stage follicles [2]. The multistep method starts with the culture of smaller follicles in situ, allowing them to develop within the natural ovarian environment (either within the whole ovary or within ovarian cortical strips). Later stage follicles are then isolated from this tissue for additional culture [43, 83, 100, 127, 132]. Multistep systems have been essential to produce mature gametes from human follicles that require extended culture. For example, Xiao et al. [22] first mechanically isolated secondary stage follicles from human ovarian cortical strips and encapsulated them in alginate. Once follicles reached 400–500 μm in diameter and formed an antrum, the follicles were released from the alginate hydrogels and cultured in low attachment plates for 30–40 days. This method was the first to lead to the production of meiotically mature oocytes from human follicles [22]. McLaughlin et al. [83] later used another multistep approach to produce MII oocytes beginning from unilaminar stage follicles. Cortical strips were first cultured in medium for 8 days (step 1). Intact follicles were dissected and cultured individually for an additional 8 days (step 2), and then COCs with mural and cumulus cells were isolated from the follicles and cultured on membranes for 4 more days (step 3). COCs with oocytes >100 μm were selected for IVM (step 4) [83]. Multistep methods have also resulted in in vitro development of primordial follicles to mature oocytes and live offspring in rodents [133].

3D culture systems have advanced follicle culture outcomes by primarily supporting follicle architecture, thereby allowing for longer culture duration, and using follicles at earlier stages such primordial and primary follicles. 3D systems have used multiple methods to support folliculogenesis such as suspension cultures, encapsulation, or even multistep systems, while maintaining follicle morphology. These systems have been absolutely essential to support the prolonged growth, survival, and development of follicles from large mammalian species, including nonhuman primates and human. Further refinement of 3D systems by introducing microfluidic systems and/or dynamic biomaterials such as natural scaffolds will improve our ability to faithfully recapitulate oogenesis and folliculogenesis in vitro [134].

Media composition varies in follicle culture studies

Supplementation of culture medium with nutrients, growth factors, and hormones is a crucial aspect of follicle culture. The medium must support cell survival and proliferation, as well as cellular function, which changes as follicles grow and oocytes mature. Media used in follicle culture is primarily basal media (minimal essential medium [MEM], Dulbecco Modified Eagle medium [DMEM], Waymouth medium, McCoy 5a medium), balanced salt solutions (Earle balanced salt solution [EBSS]), or mixed media (DMEM+F12, alpha-MEM + Glutamax), and supplements are added throughout the entire culture period or varied during culture to mimic in vivo changes in the follicle microenvironment (Supplementary Table S4). Supplements added to follicle culture media include glucose as a carbon energy source [79]; L-glutamine or fetuin (which exists in large quantities in human follicular fluid and is released by granulosa cells of growing and large follicles to maintain zona pellucida fluidity) as amino acid and protein sources, respectively, required for cell proliferation [135, 136]; antibiotics such as penicillin, streptomycin, and kanamycin; and ascorbic acid (vitamin C), which reduces apoptosis and increases follicle integrity [137]. Additionally, insulin, transferrin, selenium (ITS) is a commonly used supplement in culture media that is thought to increase uptake of metabolic precursors, such as amino acids and glucose [137], and support follicle growth and oocyte maturation [138]. FCS, fetal bovine serum, and bovine serum albumin are common protein supplements essential for follicular development in vitro [137].

Several studies have directly compared the efficacy of various culture media. For example, a study in the mouse model demonstrated that alpha-MEM, DMEM, and DMEM+F12 were superior to Waymouth medium, medium 199, Iscove Modified Dulbecco medium, and Roswell Park Memoria Institute medium (RPMI-1640) for supporting follicle survival, antrum formation, and oocyte growth, resulting in higher numbers of MII oocytes after 10 days of culture [139]. Another study found that alpha-MEM supplemented with 10% human serum and 300 mIU/mL FSH was superior to Waymouth and EBSS in the culture of human ovarian cortical tissue, with higher rates of follicular growth during a 10-day period [140]. Tissue culture medium 199 (TCM199) supplemented with 10 ng/mL EGF was superior to alpha-MEM supplemented with Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) for supporting follicle viability in the goat and for oocyte growth in the sheep during 7 days of culture [141]. Bovine preantral follicles also had a higher rate of antrum formation when cultured in TCM199 compared with alpha-MEM or McCoy 5a medium [142]. In a porcine culture model, a greater number of follicles developed antral cavities when cultured in North Carolina State University medium 23 compared with TCM199 [143].

Oxygen tension is another factor that affects folliculogenesis. Studies in rat showed that a dynamic oxygen environment, wherein the oxygen tension was changed over the culture period to mimic the in vivo transition from avascular to vascular oxygen levels, produced a higher yield of healthy and meiotically mature oocytes compared with static control [26]. In agricultural species, lower oxygen tensions are more beneficial for follicle outcomes [144]. In the caprine model, culture in 5% oxygen increased antrum formation compared with 20% oxygen [145]. Similarly, in the ovine [67] and bovine [146] models, 5% oxygen promoted follicle growth, antrum formation, and healthy COCs from preantral follicle culture. Canine COCs cultured in low oxygen tension of 5% resulted in less cumulus cell apoptosis compared with 20% oxygen [147]. In the rhesus macaque, low oxygen tension along with high FSH and fetuin resulted in increased follicle survival and growth and antrum formation [48]. These results are primarily due to 5% oxygen being closer to physiologic levels of oxygen, and higher oxygen tensions may produce more reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can have cytotoxic effects [144]. For cultures beyond 3 days, most of the studies examined replaced half of the media every other day of follicle culture. For cultures, >24 h but <3–4 days, media was usually changed daily [27, 31, 44, 75, 99, 111]. Conditioned media from these experiments have been assessed for various factors such as hormones, cytokines, and gene expression (see section on endpoints). Taken together, these studies show that optimal follicle culture media may be species dependent. Furthermore, oxygen tension closest to physiologic levels best supports culture.

Hormone supplementation in culture media is vital for folliculogenesis outcomes

Various hormones are crucial for folliculogenesis and oogenesis. Gonadotropins such as luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH are major endocrine factors that affect follicular development by stimulating the enzymes responsible for androgen production in the theca cells (LH), estrogen production, and growth and differentiation of granulosa cells (FSH). In addition, activin, GH, and insulin are necessary in various contexts in follicle culture as described below.

Due to its significant role in follicle growth, we focused on the use of FSH in the studies included in our review, comparing supplementation concentrations and regimens across species and follicle stage (Supplementary Table S5). Following the primary stage, follicles become gonadotropin dependent as FSH receptors are expressed on granulosa cells. FSH receptor signaling stimulates granulosa cell growth and proliferation [148]. FSH supplementation is often used in follicle culture, either supplied continuously throughout culture or introduced at specific time points. Recombinant and purified forms of FSH were used predominantly in the studies examined and were obtained from pituitaries of a wide range of host species including human [22, 101, 115, 128], porcine [67, 70], bovine [61, 72], ovine [37, 95], and rat [36]. FSH concentrations were variable across animal models and follicle stages and reported in international units (IU) or in nanograms per volume (1 mIU/mL corresponds to 10 ng/mL) [149]. In the mouse model, follicle growth rates and oocyte quality were higher following continuous addition of FSH (10 mIU/mL) during culture compared with FSH supplementation only at the beginning of culture [117]. In the rat model, addition of FSH to the alginate gel prior to encapsulation and to the culture medium resulted in increased follicle diameter and expression of Cx43 levels comparable with those in vivo [25]. In canine and feline models, follicles culture in the presence of FSH grew faster than follicles cultured without FSH supplementation [78, 150]. In bovine, porcine, caprine, and ovine models, FSH supplementation at increasing concentrations supported follicle growth and antrum formation, especially for culture of larger follicles, recapitulating the correlation between FSH responsiveness and follicle development in vivo [67, 71, 106, 143]. The specific concentrations of FSH used in these studies varied.

Human and nonhuman primate follicle cultures depend heavily on FSH for long-term follicle growth and higher quality oocytes. In long-term culture of rhesus macaque follicles encapsulated in alginate, higher doses of FSH (3 and 15 ng/mL) promoted greater survival rates but lower doses (0.3 ng/mL) promoted increased follicle growth [48]. In human follicles cultured for 4 weeks, a dose of 1500 mIU/mL of FSH and a 2.5 ng/mL dose of LH was required to support the growth of small follicles to the antral stage [42]. In general, FSH was not used for culturing gonadotropin-independent primordial and primary follicles [43, 58, 122]. Taken together, FSH is an integral culture medium component for supporting follicle and oocyte quality, though concentrations and supplementation protocols were highly variable.

These studies did not account for differences between FSH used, including macroheterogeneity or microheterogeneity associated with age- and cycle-specific shifts and differential bioactivity [151]. Glycosylated isoforms of human FSH can have differences in macroheterogeneity, wherein known glycosylation sites may have the presence or absence of one or more glycans, and/or microheterogeneity, wherein there is structural heterogeneity of glycans attached to the same site [152]. Changes in the relative abundance of FSH glycoforms additionally occur with age [153–159] with hypoglycosylated FSH being predominant in younger women with ovulatory cycles, and fully glycosylated FSH being predominant in older women [152–154, 159–162]. Additionally, almost every study examined for this review utilized recombinantly produced FSH unless the source was not mentioned. Only two ovine studies [67, 70] utilized pituitary bovine FSH. Significant factors such as these have never been accounted for in any culture study used, and therefore, the effects of structural differences in the gonadotropins used are unknown.

Other hormones are used as medium supplements to enhance follicle growth in vitro. Activin is a peptide hormone involved in multiple aspects of folliculogenesis such as primordial follicle activation, follicle development and growth, and interaction between the oocyte and granulosa cells [106]. Human follicles cultured with 100 ng/mL human recombinant activin grew larger and had a 30% higher survival rate compared with follicles cultured in control medium without activin [43]. Activin also augments the effects of FSH in culture medium, further increasing granulosa cell proliferation as seen in ovine and bovine models [106]. GH is a well-known factor that also stimulates follicle development and granulosa cell proliferation in addition to promoting steroidogenesis, gonadotropin responsiveness, and ovulation [144]. In the caprine model, FSH acts in combination with insulin and GH to enhance follicle growth, oocyte meiotic resumption, and estrogen production [163]. Insulin is thought to act as a survival factor by reducing follicle atresia and stimulating follicle growth in vitro. In feline studies, insulin was important for secondary follicle growth and differentiation in a concentration-dependent manner. The stimulatory effect of insulin appeared to act by regulating expression of Cyp17a1 and Star genes and progesterone production in a time-specific manner [77]. In the rhesus macaque, 5 μg/mL of insulin in the presence of FSH stimulated greater ovarian steroidogenesis in slow-growing follicles (250–500 μm) compared with 0.5 μg/mL insulin [47]. In human follicle culture, addition of insulin (in the form of ITS) or insulin-like growth factors I and II led to larger and more developed follicles with significantly less atresia than those cultured with serum alone [140, 164].

LH supplementation in mouse follicle culture induced early differentiation of theca cells, allowing for LH-dependent growth in primary and secondary follicles [165, 166]. Rhesus macaque follicles cultured in media with 10 mIU/mL LH showed greater estradiol production, likely due to proliferation of theca cells [24]. The addition of these hormones to culture media helps mimic the in vivo milieu of the ovary that is essential for in vitro growth, development, and survival of follicles. However, certain limitations exist regarding hormone supplementation. For example, many hormones are not stable long term (hence the requirement of exchanging part of the media at intervals). Additionally, as there is no consistent measure of the amount and concentration of hormones required, it is difficult to standardize protocols based on follicle stage or species. Taken together, the hormones and supplements added to follicle culture media are crucial to the growth and viability of follicles and oocytes. However, the usage of such hormones and supplements varies across studies and even within studies of similar species and follicle stages. Details of hormone and supplement sources (e.g., purified versus recombinant) are typically lacking in the literature and should be provided to ensure rigor and reproducibility across experiments. Moreover, how these supplements interact with each other and are metabolized over the culture period are largely unknown but warrant further investigation.

Quantitative oogenesis and folliculogenesis endpoints are essential for evaluating in vitro follicle growth

Defined qualitative and quantitative endpoints are necessary to evaluate follicle culture, and common parameters include follicle and oocyte outcomes, gene expression analysis, hormone output, IVF results, and other outcomes such as ROS production and cell proliferation (Supplementary Table S6).

Follicle maturation outcomes include follicle survival and growth and antrum formation. Follicular morphology and size can be measured by examination using light microscopy, making these the most common endpoints examined across studies. Follicle survival is usually classified based on criteria such as intact basement membrane and theca layer as well as morphologically normal oocytes (uniform and not granular) and granulosa cells (not pyknotic). Follicular growth is determined using diameter measurements based on the average of two perpendicular lengths measured from basement membrane to basement membrane. However, a simple increase in diameter of the follicle as a result of granulosa cell expansion does not necessarily correlate to overall follicular growth, especially in 2D cultures [118]. Moreover, in vitro, terminal follicle diameters are typically significantly smaller than those in vivo [22, 43, 83]. Antrum formation, assessed by the formation and size of a fluid-filled antral cavity, is an important measure of follicle maturation as it shows the differentiation of mural and cumulus granulosa cells [118]. Oocyte outcomes include the growth and survival of the gamete within the follicle throughout culture. Oocyte diameters increase across culture in the mouse [38], sheep [68], cow [61], rhesus [46], and human [43]; however, growth is limited after the follicle reaches a certain size. Oocytes can also autonomously undergo meiotic resumption and ovulate from follicles following hormonal stimulation [28]. Meiotic competence is a measure of oocyte maturity and is generally scored visually into different categories: Germinal vesicle (GV) with germinal vesicle present, Germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) or MI without the germinal vesicle present, MII with polar body extrusion present in the perivitelline space, or degenerate if oocytes were fragmented or shunted [28]. In addition to this, spindle integrity and chromosome alignment on the metaphase plate are important markers for oocyte developmental competence as the meiotic spindle is essential for facilitating proper chromosome segregation and producing a haploid gamete [167].

The ability of in vitro grown follicles to produce gametes that can support fertilization and preimplantation embryo development is a prime hallmark of quality. Thus, outcomes following IVF are particularly informative. Mature eggs are obtained at the end of culture either mechanically from antral follicles or by induced ovulation. Eggs are then incubated with capacitated sperm, and resulting embryos are either cultured in vitro or transferred into oviducts of animals. Fertilization rates and preimplantation embryo development are monitored. Production of live offspring is a more challenging endpoint especially when culturing follicles from large mammalian species. Thus, live birth using oocytes from cultured follicles has only been reported in murine models [38, 132, 133]. In buffalo [82], porcine [75], and ovine [70] species, live births have been reported but not exclusively by the culture methods examined in this review. Cumulus expansion and oocyte meiotic maturation after IVM have been achieved in both rhesus macaque [46] and baboon [57] follicle culture, and in human studies, meiotically competent MII-arrested oocytes have been obtained [22]. Preimplantation embryos following fertilization by ICSI or IVF were also achieved in the rhesus macaque model from COCs that underwent in vitro maturation [49] and from preantral follicles cultured in vitro [48, 52–54, 56].

Somatic cell endpoints of follicle culture include gene expression analysis and hormone production. Commonly assayed genes include those that are endocrine-related (e.g., Fshr, Cyp19a1, Hsd3b1, and Fshr), growth-related (e.g., IGFs), or oocyte-specific genes (e.g., Bmp15, Nobox, Vasa, Figlalpha, Gdf9, Jag1, Mater, Zp1, Zp2, and Zp3) [168]. Other genes such as Ptx3, Has2, and Ptgs2, which are cumulus cell-specific genes and highly critical for oocyte meiosis and developmental competence, have been examined in human studies in lieu of parthenogenesis and IVF [22].

Steroid hormones and the gene expression of their receptors are dependable targets to assess outcomes of culture. Steroid hormones can be assayed simply by sampling the conditioned media, thereby creating a powerful non-invasive tool to determine culture outcomes without using the actual follicle or oocyte that was cultured. Theca cells of the follicle synthesize progesterone and androgens, which diffuse to granulosa cells and serve as precursors for estrogen synthesis. Estrogen in turn promotes follicle growth and maturation [169]. Across studies examined in murine, nonhuman primate, and human models, estradiol and progesterone levels were positively correlated with follicle development. This is most likely due to the increase in the number of somatic cells able to secrete estrogen from growing follicles [22, 24, 48, 51, 115, 119].

Depending on the particular study, other follicle culture endpoints may be assessed. For example, autoradiography, bromodeoxyuridine labeling, or [3H]thymidine incorporation have been used to assess the mitotic index of granulosa cells as a marker of cell proliferation [58, 116]. Follicle atresia has also been evaluated histologically [110]. Follicle atresia can occur in response to oxidative stress, so ROS has been used as another follicle health endpoint [129]. The toolbox of endpoints, ranging from gene expression to hormone analysis to gamete potential, is continuously expanding. The particular endpoint selected depends on the study itself and factors such as culture duration, follicle stage, and species. Moreover, being able to quantitatively and comprehensively evaluate multiple germ and somatic cell endpoints when assessing the efficacy of in vitro follicle growth strategies is necessary.

Conclusion

The history of follicle culture has witnessed a general trend moving away from reductionist approaches and instead moving toward engineering of increasingly complex and dynamic environments which better mimic the in vivo ovarian microenvironment. Natural scaffolds obtained through decellularization of bovine ovaries followed by recellularization with granulosa, theca, and germ cells induced puberty when transplanted into ovariectomized mice, and studies to develop decellularized human ovary scaffolds and tissue papers are underway [170, 171]. Understanding the structure of the ovarian scaffold has informed the 3D printing of an ovarian bioprosthetic. Follicle-seeded microporous 3D-printed scaffolds have fully restored ovarian function and resulted in multiple generations of live offspring following transplantation into ovariectomized mice [172]. Additionally, microfluidics and other future technologies could benefit from follicle culture techniques by allowing for different system configurations to integrate according to the physiologic needs of a cell. A microfluidic system may be beneficial over static systems, because it will provide the ideal 3D environment for follicles by allowing for necessary oxygenation and nutrient exchange while permitting autocrine and paracrine signaling [118]. In human studies, factoring in the effects of the menstrual cycle is particularly important when attempting to recreate the ovarian environment in vitro. To this end, studies using alginate encapsulation [15] within the context of a microfluidic chip [89] have investigated mimicking hormonal changes of the menstrual cycle in follicle culture [2]. Microfluidics has enabled successful recapitulation of the human 28-day menstrual cycle by integrating tissues such as the mouse ovary and human fallopian tube, ectocervix, and liver [173]. These microfluidics platforms must become readily accessible to further advance the field of follicle culture among different species. Follicle culture protocols are diverse to accommodate the broad usage of this method across species, animal age, follicle stage, and specific study endpoints. Over the past decades, this technology has revealed unprecedented new knowledge of oogenesis and folliculogenesis, and continuous innovations will enable translation of basic science findings to clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Authors thank Dr. Stacey C. Tobin, PhD for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This work was supported by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Northwestern University startup funds (to FED) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD093726 to FED); the Master of Science in Reproductive Science and Medicine Program, the National Institutes of Health (AG029531, AG056046 to TRK), and the Edgar L, Patricia M Makowski and Family Endowment (to TRK).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1. Edson MA, Nagaraja AK, Matzuk MM. The mammalian ovary from genesis to revelation. Endocr Rev 2009; 30:624–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Green LJ, Shikanov A. In vitro culture methods of preantral follicles. Theriogenology 2016; 86:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. West ER, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. Engineering the follicle microenvironment. Semin Reprod Med 2007; 25:287–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matzuk MM, Burns KH. Genetics of mammalian reproduction: modeling the end of the germline. Annu Rev Physiol 2012; 74:503–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richards JS, Ascoli M. Endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine signaling pathways that regulate ovulation. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018; 29:313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smitz J, Dolmans MM, Donnez J, Fortune JE, Hovatta O, Jewgenow K, Picton HM, Plancha C, Shea LD, Stouffer RL, Telfer EE, Woodruff TK et al. Current achievements and future research directions in ovarian tissue culture, in vitro follicle development and transplantation: implications for fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Update 2010; 16:395–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marin D, Yang M, Wang T. In vitro growth of human ovarian follicles for fertility preservation. Reprod Dev Med 2018; 2:230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cortvrindt R, Smitz J. Follicle culture in reproductive toxicology: a tool for in-vitro testing of ovarian function? Hum Reprod Update 2002; 8:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu Y, Duncan FE, Xu M, Woodruff TK. Use of an organotypic mammalian in vitro follicle growth (IVFG) assay to facilitate female reproductive toxicity screening. Reprod Fertil Dev 2016. Published online ahead of print 18 February 2015. doi: 10.1071/RD14375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucci CM, Amorim CA, Rodrigues AP, Figueiredo JR, Báo SN, Silva JRV, Gonçalves PB. Study of preantral follicle population in situ and after mechanical isolation from caprine ovaries at different reproductive stages. Anim Reprod Sci 1999; 56:223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haag KT, Magalhães-Padilha DM, Fonseca GR, Wischral A, Gastal MO, King SS, Jones KL, Figueiredo JR, Gastal EL. In vitro culture of equine preantral follicles obtained via the biopsy pick-up method. Theriogenology 2013; 79:911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aguiar FL, Lunardi FO, Lima LF, Rocha RM, Bruno JB, Magalhaes-Padilha DM, Cibin FW, Nunes-Pinheiro DC, Gastal MO, Rodrigues AP, Apgar GA, Gastal EL et al. FSH supplementation to culture medium is beneficial for activation and survival of preantral follicles enclosed in equine ovarian tissue. Theriogenology 2016; 85:1106–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aguiar FL, Lunardi FO, Lima LF, Rocha RM, Bruno JB, Magalhaes-Padilha DM, Cibin FW, Rodrigues AP, Gastal MO, Gastal EL, Figueiredo JR. Insulin improves in vitro survival of equine preantral follicles enclosed in ovarian tissue and reduces reactive oxygen species production after culture. Theriogenology 2016; 85:1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aguiar FLN, Lunardi FO, Lima LF, Bruno JB, Alves BG, Magalhaes-Padilha DM, Cibin FWS, Berioni L, Apgar GA, Lo Turco EG, Gastal EL, Figueiredo JR. Role of EGF on in situ culture of equine preantral follicles and metabolomics profile. Res Vet Sci 2017; 115:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gomes RG, Lisboa LA, Silva CB, Max MC, Marino PC, Oliveira RL, Gonzalez SM, Barreiros TR, Marinho LS, Seneda MM. Improvement of development of equine preantral follicles after 6 days of in vitro culture with ascorbic acid supplementation. Theriogenology 2015; 84:750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Max MC, Bizarro-Silva C, Bufalo I, Gonzalez SM, Lindquist AG, Gomes RG, Barreiros TRR, Lisboa LA, Morotti F, Seneda MM. In vitro culture supplementation of EGF for improving the survival of equine preantral follicles. In Vitro Cell Develop Biol: Anim 2018; 54:687–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiedemann C, Zahmel J, Jewgenow K. Short-term culture of ovarian cortex pieces to assess the cryopreservation outcome in wild felids for genome conservation. BMC Vet Res 2013; 9:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griffin J, Emery BR, Huang I, Peterson CM, Carrell DT. Comparative analysis of follicle morphology and oocyte diameter in four mammalian species (mouse, hamster, pig, and human). J Exp Clin Assist Reprod 2006; 3:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pepling ME, Sundman EA, Patterson NL, Gephardt GW, Medico L Jr, Wilson KI. Differences in oocyte development and estradiol sensitivity among mouse strains. Reproduction 2010; 139:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pedersen T, Peters H. Proposal for a classification of oocytes and follicles in the mouse ovary. Reprod Fertil Dev 1968; 17:555–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirshfield AN. Development of follicles in the mammalian ovary. Int Rev Cytol 1991; 124:43–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao S, Zhang J, Romero MM, Smith KN, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. In vitro follicle growth supports human oocyte meiotic maturation. Sci Rep 2015; 5:17323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodrigues JK, Navarro PA, Zelinski MB, Stouffer RL, Xu J. Direct actions of androgens on the survival, growth and secretion of steroids and anti-Mullerian hormone by individual macaque follicles during three-dimensional culture. Hum Reprod 2015; 30:664–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu M, West-Farrell ER, Stouffer RL, Shea LD, Woodruff TK, Zelinski MB. Encapsulated three-dimensional culture supports development of nonhuman primate secondary follicles. Biol Reprod 2009; 81:587–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heise M, Koepsel R, Russell AJ, McGee EA. Calcium alginate microencapsulation of ovarian follicles impacts FSH delivery and follicle morphology. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2005; 3:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heise MK, Koepsel R, McGee EA, Russell AJ. Dynamic oxygen enhances oocyte maturation in long-term follicle culture. Tissue Eng, Part C 2009; 15:323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adam AAG, Takahashi Y, Katagiri S, Nagano M. In vitro culture of mouse preantral follicles using membrane inserts and developmental competence of in vitro ovulated oocytes. J Reprod Dev 2004; 50:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skory RM, Xu Y, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. Engineering the ovarian cycle using in vitro follicle culture. Hum Reprod 2015; 30:1386–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou C, Flaws JA. Effects of an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture on cultured mouse antral follicles. Toxicol Sci 2017; 156:217–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pangas SA, Saudye H, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. Novel approach for the three-dimensional culture of granulosa cell–oocyte complexes. Tissue Eng 2003; 9:1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wycherley G, Downey D, Kane MT, Hynes AC. A novel follicle culture system markedly increases follicle volume, cell number and oestradiol secretion. Reproduction 2004; 127:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller KP, Gupta RK, Greenfeld CR, Babus JK, Flaws JA. Methoxychlor directly affects ovarian antral follicle growth and atresia through Bcl-2- and Bax-mediated pathways. Toxicol Sci 2005; 88:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peretz J, Neese SL, Flaws JA. Mouse strain does not influence the overall effects of bisphenol A-induced toxicity in adult antral follicles. Biol Reprod 2013; 89:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oktem O, Oktay K. The role of extracellular matrix and activin-A in in vitro growth and survival of murine preantral follicles. Reprod Sci 2007; 14:358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mainigi MA, Ord T, Schultz RM. Meiotic and developmental competence in mice are compromised following follicle development in vitro using an alginate-based culture system. Biol Reprod 2011; 85:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eppig JJ. Role of serum in FSH stimulated cumulus expansion by mouse oocyte-cumulus cell complexes in vitro. Biol Reprod 1980; 22:629–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eppig JJ. Maintenance of meiotic arrest and the induction of oocyte maturation in mouse oocyte-granulosa cell complexes developed in vitro from preantral follicles. Biol Reprod 1991; 45:824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu M, Kreeger PK, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. Tissue-engineered follicles produce live, fertile offspring. Tissue Eng 2006; 12:2739–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chia R, Achilli F, Festing MF, Fisher EM. The origins and uses of mouse outbred stocks. Nat Genet 2005; 37:1181–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beck JA, Lloyd S, Hafezparast M, Lennon-Pierce M, Eppig JT, Festig MFW, Fisher EMC. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat Genet 2000; 24:23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Jackson Laboratory Nomenclature of hybrid mice. 2019. http://www.informatics.jax.org.

- 42. Abir R, Franks S, Mobberley M, Moore P, Margara R, Winston R. Mechanical isolation and in vitro growth of preantral and small antral human follicles. Fertil Steril 1997; 68:682–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Telfer E, McLaughlin M, Ding C, Thong K. A two-step serum-free culture system supports development of human oocytes from primordial follicles in the presence of activin. Hum Reprod 2008; 23:1151–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roy SK, Treacy BJ. Isolation and long-term culture of human preantral follicles. Fertil Steril 1993; 59:783–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xu M, Barrett SL, West-Farrell E, Kondapalli LA, Kiesewetter SE, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. In vitro grown human ovarian follicles from cancer patients support oocyte growth. Hum Reprod 2009; 24:2531–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peluffo MC, Barrett SL, Stouffer RL, Hennebold JD, Zelinski MB. Cumulus-oocyte complexes from small antral follicles during the early follicular phase of menstrual cycles in rhesus monkeys yield oocytes that reinitiate meiosis and fertilize in vitro. Biol Reprod 2010; 83:525–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu J, Bernuci MP, Lawson MS, Yeoman RR, Fisher TE, Zelinski MB, Stouffer RL. Survival, growth, and maturation of secondary follicles from prepubertal, young, and older adult rhesus monkeys during encapsulated three-dimensional culture: effects of gonadotropins and insulin. Reproduction 2010; 140:685–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu J, Lawson MS, Yeoman RR, Pau KY, Barrett SL, Zelinski MB, Stouffer RL. Secondary follicle growth and oocyte maturation during encapsulated three-dimensional culture in rhesus monkeys: effects of gonadotropins, oxygen and fetuin. Hum Reprod 2011; 26:1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Peluffo MC, Ting AY, Zamah AM, Conti M, Stouffer RL, Zelinski MB, Hennebold JD. Amphiregulin promotes the maturation of oocytes isolated from the small antral follicles of the rhesus macaque. Hum Reprod 2012; 27:2430–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hornick JE, Duncan FE, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. Isolated primate primordial follicles require a rigid physical environment to survive and grow in vitro. Hum Reprod 2012; 27:1801–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Peluffo MC, Hennebold JD, Stouffer RL, Zelinski MB. Oocyte maturation and in vitro hormone production in small antral follicles (SAFs) isolated from rhesus monkeys. J Assist Reprod Genet 2013; 30:353–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu J, Lawson MS, Yeoman RR, Molskness TA, Ting AY, Stouffer RL, Zelinski MB. Fibrin promotes development and function of macaque primary follicles during encapsulated three-dimensional culture. Hum Reprod 2013; 28:2187–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ting AY, Xu J, Stouffer RL. Differential effects of estrogen and progesterone on development of primate secondary follicles in a steroid-depleted milieu in vitro. Hum Reprod 2015; 30:1907–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xu J, McGee WK, Bishop CV, Park BS, Cameron JL, Zelinski MB, Stouffer RL. Exposure of female macaques to western-style diet with or without chronic T in vivo alters secondary follicle function during encapsulated 3-dimensional culture. Endocrinology 2015; 156:1133–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Baba T, Ting AY, Tkachenko O, Xu J, Stouffer RL. Direct actions of androgen, estrogen and anti-Mullerian hormone on primate secondary follicle development in the absence of FSH in vitro. Hum Reprod 2017; 32:2456–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu J, Xu F, Lawson M, Tkachenko O, Ting A, Kahl C, Park B, Stouffer R, Bishop C. Anti-Mullerian hormone is a survival factor and promotes the growth of rhesus macaque preantral follicles during matrix-free culture. Biol Reprod 2018; 98:197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xu M, Fazleabas AT, Shikanov A, Jackson E, Barrett SL, Hirshfeld-Cytron J, Kiesewetter SE, Shea LD, Woodruff TK. In vitro oocyte maturation and preantral follicle culture from the luteal-phase baboon ovary produce mature oocytes. Biol Reprod 2011; 84:689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schotanus K, Hage WJ, Vanderstichele H, Hurk R. Effects of conditioned media from murine granulosa cell lines on the growth of isolated bovine preantral follicles. Theriogenology 1997; 48:471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wandji SA, Eppig JJ, Fortune JE. FSH and growth factors affect the growth and endocrine function in vitro of granulosa cells of bovine preantral follicles. Theriogenology 1996; 45:817–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yamamoto K, Otoi T, Koyama N, Horikita N, Tachikawa S, Miyano T. Development to live young from bovine small oocytes after growth, maturation and fertilization in vitro. Theriogenology 1999; 52:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gutierrez CG, Ralph JH, Telfer EE, Wilmut I, Webb R. Growth and antrum formation of bovine preantral follicles in long-term culture in vitro. Biol Reprod 2000; 62:1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Itoh T, Kacchi M, Abe H, Sendai Y, Hoshi H. Growth, antrum formation, and estradiol production of bovine preantral follicles cultured in a serum-free medium. Biol Reprod 2002; 67:1099–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rossetto R, Santos RR, Silva GM, Duarte ABG, Silva CMG, Campello CC, Figueiredo JR. Comparative study on the in vitro development of caprine and bovine preantral follicles. Small Ruminant Res 2013; 113:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Araujo VR, Gastal MO, Wischral A, Figueiredo JR, Gastal EL. In vitro development of bovine secondary follicles in two- and three-dimensional culture systems using vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and growth hormone. Theriogenology 2014; 82:1246–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Araujo VR, Gastal MO, Wischral A, Figueiredo JR, Gastal EL. Long-term in vitro culture of bovine preantral follicles: effect of base medium and medium replacement methods. Anim Reprod Sci 2015; 161:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Antonino DC, Soares MM, Junior JM, Alvarenga PB, Mohallem RFF, Rocha CD, Vieira LA, Souza AG, Beletti ME, Alves BG, Jacomini JO, Goulart LR et al. Three-dimensional levitation culture improves in-vitro growth of secondary follicles in bovine model. Reprod Biomed Online 2018; 38:300–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cecconi S, Barboni B, Coccia M, Mattioli M. In vitro development of sheep preantral follicles. Biol Reprod 1999; 60:594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Thomas FH, Leask R, Srsen V, Riley SC, Spears N, Telfer EE. Activin promotes oocyte development in ovine preantral follicles in vitro. Reproduction 2003; 122:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Muruvi W, Picton HM, Rodway RG, Joyce IM. In vitro growth of oocytes from primordial follicles isolated from frozen-thawed lamb ovaries. Theriogenology 2005; 64:1357–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Arunakumari G, Shanmugasundaram N, Rao VH. Development of morulae from the oocytes of cultured sheep preantral follicles. Theriogenology 2010; 74:884–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ferreira ACA, Cadenas J, Sa NAR, Correia HHV, Guerreiro DD, Lobo CH, Alves BG, Maside C, Gastal EL, Rodrigues APR, Figueiredo JR. In vitro culture of isolated preantral and antral follicles of goats using human recombinant FSH: concentration-dependent and stage-specific effect. Anim Reprod Sci 2018; 196:120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Silva GM, Rossetto R, Chaves RN, Duarte AB, Araujo VR, Feltrin C, Bernuci MP, Anselmo-Franci JA, Xu M, Woodruff TK, Campello CC, Figueiredo JR. In vitro development of secondary follicles from pre-pubertal and adult goats cultured in two-dimensional or three-dimensional systems. Zygote 2015; 23:475–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Magalhaes DM, Duarte AB, Araujo VR, Brito IR, Soares TG, Lima IM, Lopes CA, Campello CC, Rodrigues AP, Figueiredo JR. In vitro production of a caprine embryo from a preantral follicle cultured in media supplemented with growth hormone. Theriogenology 2011; 75:182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hirao Y, Nagai T, Kubo M, Miyano T, Miyake M, Kato S. In vitro growth and maturation of pig oocytes. Reproduction 1994; 100:333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wu J, Carrel DT, Wilcoz AL. Development of in vitro-matured oocytes from porcine preantral follicles following intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Biol Reprod 2001; 65:1579–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Songsasen N, Thongkittidilok C, Yamamizu K, Wildt DE, Comizzoli P. Short-term hypertonic exposure enhances in vitro follicle growth and meiotic competence of enclosed oocytes while modestly affecting mRNA expression of aquaporin and steroidogenic genes in the domestic cat model. Theriogenology 2017; 90:228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Thongkittidilok C, Singh RP, Comizzoli P, Wildt D, Songsasen N. Insulin promotes preantral follicle growth and antrum formation through temporal expression of genes regulating steroidogenesis and water transport in the cat. Reprod Fertil Dev 2018; 30:1369–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Songsasen N, Woodruff TK, Wildt DE. In vitro growth and steroidogenesis of dog follicles are influenced by the physical and hormonal microenvironment. Reproduction 2011; 142:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nation A, Selwood L. The production of mature oocytes from adult ovaries following primary follicle culture in a marsupial. Reproduction 2009; 138:247–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Roy SK, Greenwald GS. Hormonal requirements for the growth and differentiation of hamster preantral follicles in long-term culture. Reproduction 1989; 87:103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Daniel SAJ, Armstrong DT, Gore-Langton RE. Growth and development of rat oocytes in vitro. Gamete Res 1989; 24:109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gupta PS, Ramesh HS, Manjunatha BM, Nandi S, Ravindra JP. Production of buffalo embryos using oocytes from in vitro grown preantral follicles. Zygote 2008; 16:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. McLaughlin M, Albertini DF, Wallace WHB, Anderson RA, Telfer EE. Metaphase II oocytes from human unilaminar follicles grown in a multi-step culture system. Mol Hum Reprod 2018; 24:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tingen C, Rodriguez S, Campo-Engelstein L, Woodruff TK. Politics and parthenotes. Science 2010; 330:453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]