Highlights

-

•

Examines impacts, coping strategies, and adjustments in light of COVID-19.

-

•

Selects an international sample of hospitality operations.

-

•

Considers insights of the resilience literature and theory.

-

•

Develops theoretical frameworks emerging from the chosen inductive approach.

-

•

Proposes theoretical and practical implications can illuminate future research.

Keywords: COVID-19, Resilience, Concerns, Coping, Changes, Adjustments, Hospitality businesses, Extreme context

Abstract

Drawing on the theory of resilience, and on an international sample of 45 predominantly small hospitality businesses, this exploratory study extends knowledge about the key concerns, ways of coping, and the changes and adjustments undertaken by these firms’ owners and managers during the COVID-19 outbreak. The various emergent relationships between the findings and the considered conceptual underpinnings of the literature on resilience, revealed nine theoretical dimensions. These dimensions critically illuminate and extend understanding concerning the actions and alternatives owners-managers resorted to when confronted with an extreme context. For instance, with financial impacts and uncertainty being predominant issues among participants, over one-third indicated actioning alternative measures to create much-needed revenue streams, and preparing for a new post-COVID-19 operational regime, respectively. Furthermore, 60 percent recognised making changes to the day-to-day running of the business to respond to initial impacts, or biding time in anticipation of a changing business and legal environment.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic represents the ultimate test for numerous leaders, entrepreneurs, and employees operating in most if not all industries. Among other impacts, the contagion has severely affected the world economy (Eggers, 2020; OECD, 2020), including the travel, tourism and hospitality industries (Nicola et al., 2020). Moreover, the unprecedented nature of COVID-19 (Gössling et al., 2020) has had crippling effects, with numerous restrictions on businesses, resulting in far reaching impacts on hotels, restaurants, bars, and other hospitality businesses, with overall serious and seemingly unsurmountable challenges for the hospitality industry.

More precisely, the unfolding events of the COVID-19 epidemic in January of 2020 caused an almost 90% decrease of China’s hotel occupancy (Nicola et al., 2020). In the United States, revenue per available room fell by 11.6% (Nicola et al., 2020), while in March 2020 alone, a one-third decline in restaurant spending was noticed (Baker et al., 2020). A similar effect has been noticed in Europe, where current estimations highlight a monthly loss of one billion euros in tourism revenues as a result of COVID-19 (European Parliament, 2020).

Given the fast-paced developments of the COVID-19 threat, much of the research is currently under construction or predominantly conceptual, with researchers, for instance, offering critical commentaries (e.g., Baum and Hai, 2020; Gössling et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2020), seeking to estimate potential short, medium, and long-term consequences. Empirical research considering the perspective of the ‘coal face’ of hospitality and tourism, including owners-managers’ viewpoints, could be extremely useful for the industry in terms of practical strategies and responsiveness, while for the research community it could provide theoretical footprints with wider usefulness to further understanding.

From an empirical-business perspective, the study’s key objective is to identify the perceived impacts, adaptive measures, changes and adjustments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study focuses on small and medium enterprises (SMEs) operating in hospitality and tourism settings. The SMEs group is considered a key socioeconomic pillar in every economy, making substantial contributions through employment, competitiveness, innovation and overall economic activity (Eggers, 2020).

However, SMEs can be severely affected by major disruptions requiring a high degree of resilience, for instance, during acute economic crises (Pal et al., 2014). At the same time, SME entrepreneurs are known for their capabilities that enable their firms to be resilient, having themselves directly experienced adversity, or operated in uncertain environments (Branicki et al., 2018). Given their smaller size, SMEs have more flexibility when threats or opportunities present themselves in their environment (Eggers, 2020). Thus, SMEs possess characteristics that could help them survive crises (Eggers, 2020), and, as Kuckertz et al. (2020) observe, one could expect them to exhibit these characteristics during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study will examine three key dimensions, which are verbalised through the following research questions:

What are participants’ most pressing concerns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic?

How are their businesses coping with this major disruption? How do participants describe the effects of the pandemic in terms of changes or adjustments to their day-to-day business activities?

Addressing these questions could improve knowledge and awareness regarding the actions and reactions, or lack thereof, owners and managers of these firms undertake or choose in times of extreme contexts. Hannah et al. (2009) identify three events representing an extreme context: 1) the potential for massive material, physical, or psychological consequences, 2) consequences are perceived unbearable by members of an organisation, and 3) the magnitude of the consequences exceeds an organisation’s capacity to prevent them from occurring.

Overall, in these times of uncertainty and for many despair, learning how businesses seek to respond or cope with this unparalleled situation could also be invaluable for other stakeholders to understand and to consider a range of available options. These stakeholders are not only limited to start-ups potentially facing a similar event in the future, but also to chambers of commerce, in supporting SMEs through knowledge-sharing or technology, and to government bodies, in allocating and prioritising financial and other forms of aid.

From a theoretical standpoint, a primary objective of the present research is to develop new theoretical notions that contribute to a more rigorous reflective process of the associations between the impacts of the pandemic and the actions and reactions undertaken by firm owners-managers. Such understanding will be represented and reinforced through the proposition of theoretical frameworks. Therefore, this exploratory research considers an inductive approach, which draws on detailed readings of raw data, in this case, originating from responses to the research questions, to develop a model, themes, or concepts that ensue from a researcher’s interpretations of the raw data (Thomas, 2006). The resulting theoretical frameworks rest on nine revealed theoretical dimensions, and highlight various implications. For instance, understanding ways of coping through a self-reliant theoretical dimension underlines action and reaction in swiftly seeking financial mitigation.

2. Literature review

Investigating businesses’ capacity to adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic, or the extent to which they undertake changes and adjustments in this new regime merits consideration of associated theoretical underpinnings and concepts. Such is the case of the theory of resilience, which can enrich understanding concerning firms’ dealing with current and indeed future extreme events.

2.1. Resilience

Prior scholarship has considered the highly numerous conceptualisations drawn on to define resilience. In presenting as many as 21 definitions developed in earlier studies, Norris et al. (2008) explain that common themes arising from these conceptualisations are the capacity to adapt successfully when facing adversity, stress or disturbance. Norris et al. (2008) propose their own definition referring to a theory of resilience in terms of “a process linking a set of adaptive capacities to a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation after a disturbance” (p. 130). Furthermore, resilience is a dynamic condition (Brown et al., 2017), and can ensue when resources are rapidly accessible or robust, allowing for counteracting the impacts of a stressor, and as a result enabling a return to functioning adapted to the changed environment (Norris et al., 2008). However, while resilience formalisation represents “an indicator of preparedness and capability to cope with a crisis” (Herbane, 2019, p. 487), it is not a guarantee of successful recovery. Indeed, some organisations might be able to overcome a crisis without preparedness (Herbane, 2019).

Numerous studies have discussed the relevance of resilience in the domain of SMEs. For instance, research among European SMEs (Ates and Bititci, 2011) revealed the importance of change management process capabilities in enhancing resilience, notably, by implementing long term planning, embracing operational elements of change management, and consideration of people and organisational dimensions. In this context, innovative responses through improvements and continuous changes are crucial for firms’ sustainability and resilience (Ates and Bititci, 2011).

More recently, Pal et al. (2014) proposed a model of SME resilience, which stressed the significance of three key assets, with the first being represented by firms’ resourcefulness, notably, their material, social, or intangible capabilities. The second, dynamic competitiveness, emphasises the value of flexibility, robustness, networking, or redundancy, or the degree to which some elements can be substitutable in the eventuality of disruption (Pal et al., 2014). Learning and culture, the third asset, highlights the role of leadership, collectiveness, sense making, and employee well-being (Pal et al., 2014). Partly associated with these assets is the notion of mobilisation of resources and capabilities, with potential key benefits for industry and the surrounding stakeholders (Sainaghi et al., 2019).

2.2. Conceptual research - Resilience in the tourism and hospitality industries

In connection with SME research, a number of authors have discussed resilience in light of disasters affecting the tourism and hospitality industries, thereby developing theoretical notions and arguments. Among others, Brown et al. (2017) discussed different types of resilience, namely community, economic, organisational, and systems, all of which have important implications for hotels. Brown et al. (2017) concluded highlighting the significance of prioritising disaster resilience among hotels, which involves “a dynamic condition describing the capacity of the organisation” (p. 368) and its stakeholders, to adapt, innovate, assess, and ultimately overcome potential disruptions. Thus, adaptive capacity, flexibility, or fostering a culture which promotes innovation and self-efficacy, are key factors in improving organisational resilience (Brown et al., 2017).

Bandura’s (1991) perceived self-efficacy theory can also shed light on resilience. The intersections between self-efficacy and one’s performance can be suggested “through its strong effects on personal goal setting and proficient analytic thinking” (Bandura, 1991, p. 271). Accordingly, perceived self-efficacy affects performance attainments and motivation, for instance, through impact on outcome expectation or goals (Bandura, 2000). Moreover, and in connection with the present study’s focus, self-efficacy is instrumental in supporting one’s persistence in the face of aversive experiences and obstacles (Bandura and Adams, 1977), affecting task effort, the level of goal difficulty chosen for performance, or expressed interest (Gist, 1987).

Further extending the theory of resilience, Brown et al. (2018) proposed an integrative framework based upon six forms of capital specifically geared towards developing disaster resilience in the hotel sector:

Cultural, such as cultural knowledge or influence on a social system,

Economic, including the availability of resources and financial strength,

Human, which focuses on skills, capacity to adapt, or knowledge,

Natural, for instance, a location’s effects on the environment,

Physical, involving life safety or business continuity,

Social capital, entailing social networks or trust.

2.3. Empirical research - Resilience in the tourism and hospitality industries

From an empirical perspective, Lamanna et al. (2012) illuminated the devastating consequences, both operationally and concerning human resources, among hotels experiencing extreme weather events (Hurricane Gustav, 2008). Lamanna et al. (2012) also recognised that hotels operating in Great New Orleans demonstrated more wide-spread planning, better preparedness, and generally “more efficient disaster management process” (p. 220), thus emphasising some of the conceptual ideas proposed by subsequent research (Brown et al., 2018). Sydnor-Bousso et al.’s (2011) research in numerous United States’ counties affected by disasters is similarly in line with Brown et al.’s (2018) contribution depicting various types of capital in resilience-building. Sydnor-Bousso et al. (2011) found that physical capital (local infrastructure), as well as human and social capital were determinant variables helping the hospitality industry build resilience.

Another study in the hospitality sector (Tibay et al., 2018) revealed the associations between resilience and perceptions of viability as a business, withstanding unexpected financial issues or seasonal customer fluctuations, as well as the significance of core competencies, leadership and management, situational awareness and market sensitivity. However, there was a lack of planning among businesses for such unexpected events as large scale disasters (Tibay et al., 2018). This conclusion is partly contradicted by Brown et al.’s (2019) research, which in referring to New Zealand hotels, concludes that strategies and systems for disaster response or preparedness are adequate in most properties, and reflect the country’s recent experiences with earthquakes.

In contrast to major disasters, research on upscale restaurants by Hallak et al. (2018) identifies adversity through changing consumer demands, which requires innovation and creativity to respond to market dynamics and build much-needed resilience. From their empirical data Hallak et al. (2018) proposed a theoretical framework, where business resilience is strongly related to creative self-efficacy, and to innovation, with direct impacts on firm performance. The authors drew on the work of Tierney and Farmer (2002) to conceptualise creative self-efficacy in terms of one’s belief in possessing the ability to produce creative outcomes.

While the above academic literature provides relevant conceptual and empirical insights into the domain of resilience, the recent COVID-19 epidemic poses unique challenges to millions of businesses. Indeed, a survey of nearly 6000 United States small firms (Bartik et al., 2020) illustrates the serious predicament owners and managers confront concerning mass closures and layoffs, further weakening the already fragile financial position of this group of firms. Moreover, with 43 percent of the surveyed businesses temporarily closed and 40 percent of the workforce affected, the situation is almost unparalleled since the 1930s (Bartik et al., 2020). The unexpected severe turbulence caused by COVID-19 therefore calls for a reconsideration of the theorisation of resilience, for instance, taking into account new forms of adaption and courses of action.

3. Methodology

This exploratory study has two specific objectives. First, drawing on the experiences and interpretations of owners and managers, it seeks to identify the impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality businesses, adaptive approaches, and planned or enacted changes and adjustments to respond, adapt, and build resilience from the perspective of owners and managers. Second, the study proposes various theoretical frameworks, which can inform the research and increase understanding of the themes under examination. As previously suggested, the study considers an inductive approach, which allows for a theoretical framework to emerge from “the underlying structure of experiences or processes that are evident in the text data” (Thomas, 2006, p. 237). According to Barczak (2015), qualitative research, which this exploratory study is based upon, “typically follows an inductive approach to advance and build theory” (p. 658).

To collect and analyse raw data, eliciting the thoughts and experiences of knowledgeable and experienced individuals at the coal face of hospitality activities was fundamental. Thus, a purposeful sampling method was adopted, in that information-rich cases are strategically considered, as their substance and nature contribute to illuminating the areas under study (Patton, 2015). The purposive sampling criteria applied to this study was primarily based upon the following eligibility requirements for businesses and participants:

-

a)

Be associated with the hospitality industry,

-

b)

Be an owner or manager or both,

-

c)

Respondents must have been involved in the hospitality industry for at least three years.

During April and May of 2020, contact was established with businesses in eight different countries. This geographic broadness was meant to provide an international perspective to the studied themes, and although not part of the research objectives, potentially identify differences based upon geographic location. The businesses were identified by different members of the research team through their own website, as well as through their inclusion in chambers of commerce’s websites. When selecting countries, a key criterion was that members of the research team be residents or reside in close geographic proximity, which was perceived as strategically important. First, sharing similar language and culture facilitated and enabled the establishment of rapport and communication between researcher and potential respondents. Second, and concerning these aspects, given the lockdown and related government protocols that rendered meetings to conduct face-to-face interviews unfeasible, the geographic proximity to potential respondents enabled the research team members to clarify queries prior to respondents’ completion of the survey.

Utilising a survey research approach, respondents were contacted by electronic correspondence and provided with a participant information sheet with a link to an online survey. Given the travel restrictions in place and social distancing, the online survey was utilised not only to ensure the safety of participants but enabled the collection of data internationally. All responses were anonymous, ensuring confidentiality and privacy. The total number of businesses contacted by electronic correspondence was 96, or 12 in each country; this number of contacts was believed to generate a sufficient number of responses. In the context of the present study, one section of the online questionnaire gathered demographic data from participants and their firms (Table 1 ), while another section focused on three key themes verbalised through the following open-ended questions:

-

1)

What are your biggest concerns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in regard to your business?

-

2)

How is your business coping with this major disruption?

-

3)

How would you describe the effects of the pandemic, in terms of changes/adjustments to your day-to-day activities?

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants and their firms.

| n | Country a | Role | Gender | Type of firm b | Experiencec | Full-time staff | Age of the firmc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AR1 | Manager | Female | Winery | 8 | 35 | 15 |

| 2 | AR2 | Manager | Female | Winery | 22 | 5 | 25 |

| 3 | AR3 | Manager | Female | Winery | 4 | 5 | 20 |

| 4 | AR4 | Owner | Female | Hotel | 18 | 15 | 16 |

| 5 | AR5 | Manager | Male | Winery | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | AR6 | Manager | Female | Winery | 6 | 10 | 20 |

| 7 | AR7 | Manager | Female | Winery | 20 | 10 | 25 |

| 8 | AUS1 | Manager | Male | Café | 20 | 8 | 2 |

| 9 | AUS2 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 28 | 40 | 8 |

| 10 | AUS3 | Owner | Male | Café | 20 | 3 | 12 |

| 11 | AUS4 | Manager | Male | Café | 5 | 6 | 2 |

| 12 | AUS5 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 15 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | AUS6 | Owner | Female | Café | 10 | 3 | 5 |

| 14 | AUS7 | Owner | Male | Café | 20 | 4 | 1 |

| 15 | AUS8 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 15 | 6 | 5 |

| 16 | AUS9 | Owner | Female | Restaurant | 11 | 20 | 10 |

| 17 | BO1 | Manager | Male | Hotel | 10 | 4 | 20 |

| 18 | BO2 | Owner | Female | Hotel | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| 19 | BO3 | Owner | Female | Hotel | 7 | 4 | 28 |

| 20 | GR1 | Manager | Male | Hotel | 38 | 22 | 20 |

| 21 | GR2 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 20 | 4 | 7 |

| 22 | GR3 | Manager | Male | Hotel | 18 | 18 | 22 |

| 23 | GR4 | Owner | Male | Hotel | 45 | 4 | 40 |

| 24 | GR5 | Manager | Female | Hotel | 12 | 13 | 25 |

| 25 | GR6 | Manager | Female | Hotel | 29 | 30 | 20 |

| 26 | GR7 | Manager | Female | Hotel | 20 | 35 | 40 |

| 27 | IT1 | Owner | Male | Agritourism | 30 | 4 | 50 |

| 28 | IT2 | Owner | Male | Agritourism | 15 | 3 | 25 |

| 29 | IT3 | Owner | Female | Hotel | 25 | 6 | 25 |

| 30 | IT4 | Owner | Male | Café | 15 | 6 | 15 |

| 31 | IT5 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 30 | 8 | 26 |

| 32 | IT6 | Owner | Female | Restaurant | 15 | 4 | 25 |

| 33 | IT7 | Owner | Female | Agritourism | 7 | 3 | 5 |

| 34 | IT8 | Owner | Male | Hotel | 40 | 15 | 63 |

| 35 | MA1 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 10 | 35 | 8 |

| 36 | MA2 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 12 | 20 | 12 |

| 37 | MA3 | Owner | Male | Café | 5 | 10 | 4 |

| 38 | SP1 | Owner | Female | Hotel | 28 | 12 | 25 |

| 39 | SP2 | Owner | Male | Winery | 30 | 3 | 80 |

| 40 | SP3 | Manager | Male | Winery | 16 | 32 | 32 |

| 41 | UK1 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 10 | 13 | 8 |

| 42 | UK2 | Owner | Male | Bar | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| 43 | UK3 | Owner | Male | Restaurant | 27 | 5 | 14 |

| 44 | UK4 | Manager | Male | Hotel | 14 | 50 | 35 |

| 45 | UK5 | Manager | Male | Hotel | 20 | 70 | 52 |

Coding for participants according to countries: Argentina: AR; Australia: AUS; Bolivia: BO; Greece: GR; Italy: IT; Malaysia: MA; Spain: SP; United Kingdom: UK.

All wineries offered onsite catering and tasting room and; agritourism firms offered onsite catering and accommodation.

Catering for guests/customers; in years.

When developing the above questions, the insights of various studies that examined hospitality firms facing extreme events, as well as research investigating resilience among hospitality businesses were considered, for instance, in the ideation process (e.g., Dobie et al., 2018; Gruman et al., 2011; Lamanna et al., 2012; Orchiston, 2013; Tibay et al., 2018). The questionnaire was translated into different languages (e.g., Greek, Italian, Spanish) by members of the research team, and back to English upon receiving the responses. Similarly, members of the research team were involved in cross-checking in this second translation, thus, ensuring for clarity and consistency of the translated material.

As many as 45 individuals representing as many firms completed the questionnaire, a 46.9% response rate. While for analysis purposes this number is appropriate, given the millions of existing hospitality businesses around the world, the overall results must be treated with prudence regarding their generalisability.

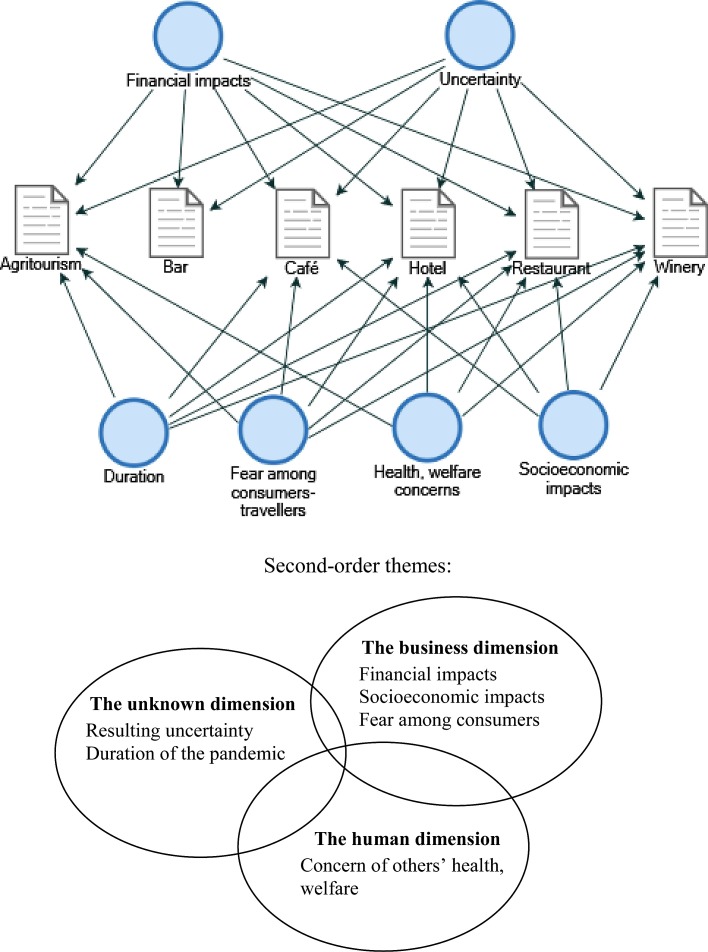

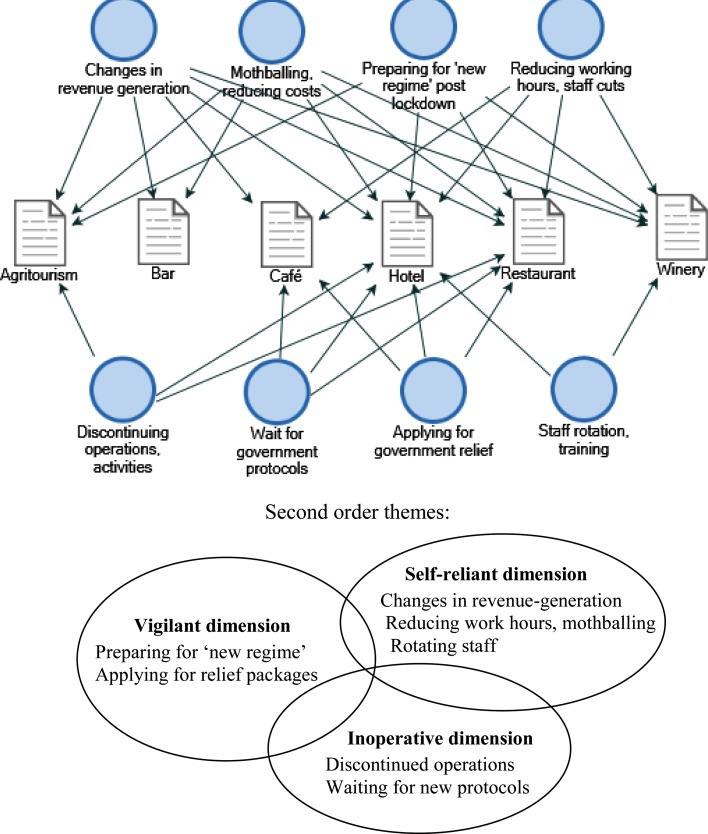

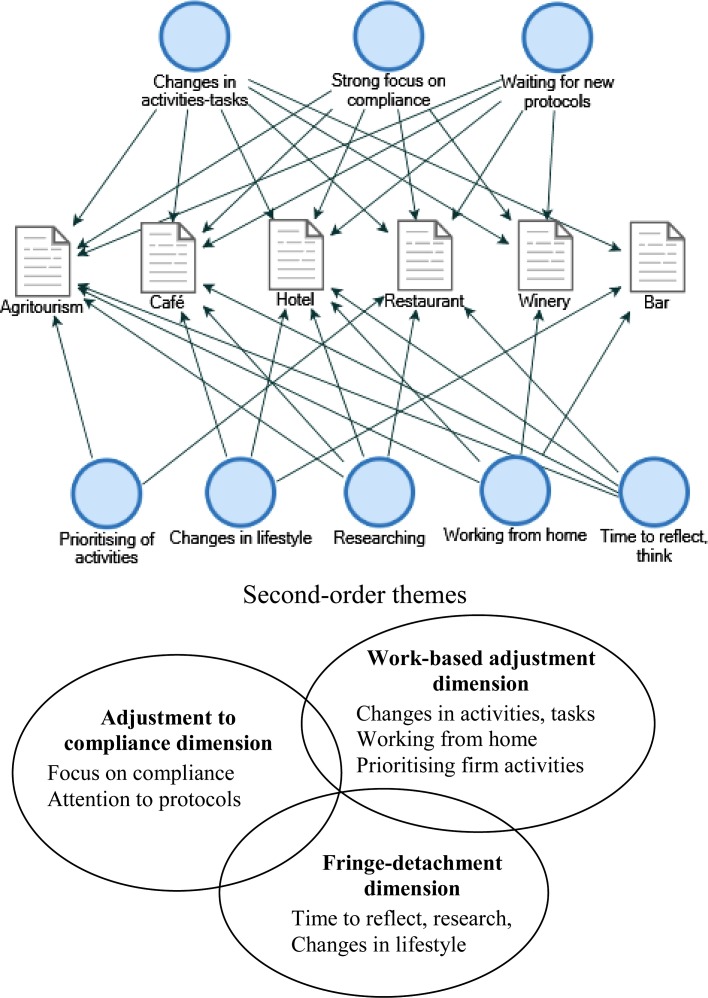

The qualitative responses were then analysed by members of the research team through content analysis, systematically identifying, classifying and coding patterns drawn from the content of text data (e.g., Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS) software NVivo version 12 was utilised in the coding process and to develop visualisations of the associations in the dataset. This tool can also assist researchers in reporting from, and in visualising the data (Bazeley and Jackson, 2013), for instance, through the creation of nodes, mind maps or models, which in the present research are presented through Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 . Recurrent and emergent themes were then cross-checked by the research team to ensure coding reflected the issues identified by respondents, ensuring validity.

Fig. 1.

Major concerns associated with the pandemic and associated second-order themes.

Fig. 2.

Key ways of coping with COVID-19.

Fig. 3.

Key ways of changing-adjusting to COVID-19.

Associated with the inductive approach, in analysing the data, theory development could be enhanced through the organisation of first-order codes, which are more descriptive and fragmented, into second-order themes, which are theory-centric (Gioia et al., 2012). As a result, second-order themes can be distilled “into overarching theoretical dimensions” (Gioia et al., 2012, p. 26); these again are represented by Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3.

In the following sections, participants from the eight different nations will be labelled using an acronym, where the nation’s name is shortened and followed by a number. For instance, participants from Argentina are labelled as AR1 and AR2, participants from Italy as IT1 and IT2, while participants from the United Kingdom (UK) are labelled as UK1 and UK2. In addition, Table 1 provides a comprehensive depiction of how participants from all the selected nations were labelled.

3.1. Demographic information of participants and firms

The data analysis reveals that an equal percentage of participants are business owners and males (62.2%). Hotels (33.3%) represent the main sector of the sample, followed by restaurants (24.4%), wineries (17.8%), and cafés (15.6%). All participating wineries provide catering and tasting facilities and therefore qualify as hospitality businesses. Participants’ experience working at their chosen industry ranges between 4 and 45 years, with the largest group (19, 42.2%) indicating at least 20 years of experience. The age of the businesses ranges between 1 and 80 years, with most (29, 64.4%) being established for over a decade. Based on various definitions associated with the size of firms in different geographical locations (Argentinian Government, 2018; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2002; Durán, 2009; Gatto, 1999; European Commission, 2003), all the participating firms belong to the SME category.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Key concerns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic

Based upon premises regarding theory development from inductive research (Barczak, 2015; Gioia et al., 2012; Thomas, 2006), Fig. 1 illustrates various relationships between first-order themes and the different sectors representing the participating firms. In further considering Gioia et al.’s (2012) contribution, the results suggest three second-order themes representing ‘business’, ‘the unknown’, and ‘human dimensions’, all of which derive from the emerging first-order codes, or from multiple comments. These dimensions contribute to understanding the discourses underpinning relationships between business and against the backdrop of an extreme context (Hannah et al., 2009), where a myriad of concerns can systematically engulf business owners and managers.

Queried about the most pressing concerns for their business as a result of COVID-19, most participants (86.7%) voiced at least one fundamental issue. By far (84.4%), financial impacts emerged among participants’ responses, distantly followed by the climate of uncertainty that the pandemic had created. These two issues were also prevalent among all the different business sectors. Another major disruption to participants’ businesses was the abrupt discontinuing of operations as a result of fear among customers and travellers. These challenges were further intensified by self-isolation and quarantine requirements that altogether prevented citizens from patronising hospitality businesses.

Concerning the developed theoretical insights of this research, first, the business dimension emerged through potentially devastating issues for participants’ business and industry. These issues were predominantly socioeconomic consequences, alongside the perceived ensuing fear among customers and travellers, which were demonstrated through cancellations and discontinued patronage:

AU3: My main concern is how to sustain the business when office workers in the CBD are staggering their return to their city office workplaces… paying expenses, specifically the fixed costs like rent, electricity, insurance, and wages…

BO2: We have earned no income in three months… Thus, we cannot cover the wages of all the workers, the regular payment of water, electricity, telephone services, internet, and cable TV.

GR3: Main impacts are low room occupancy, reduced profit, high payroll expenses, and reduced arrival flights from abroad due to the uncertainty.

Second, the extended comments, some of which were associated with the business dimension, further underlined the unknown element was also a motive of concern, as well as an indication that ‘business as usual’ was not to resume in the foreseeable future:

AR6: Suddenly, we have a closed, desolate winery, with no one to visit us…

IT2: The main concerns are related to the fact that in the coming months we will not have the influx of tourists necessary to cover the costs…

Third, and similarly, comments intersected various dimensions, emphasising their inter-relationships, as the pandemic had created multiple disturbances simultaneously. In the case of UK5, who manages a hotel, the business dimension overlapped with the human aspect, in this case, where the well-being of the business had key implications for employees’ welfare. Moreover, UK5’s observations revealed two key concerns: the devastating impacts on the financial health of the business and the domino effects on the future employability of the staff:

Within weeks I have gone from operating a financially strong and busy hotel, running an average annual occupancy of 92%, falling to 10%… the forecast for the next 12 months looks to peak at about 60% occupancy in April 2021, meaning that there will be no work for about half of the workforce.

However, in various instances, the human dimension also included participants’ own struggles with the tragic events following the COVID-19 outbreak. UK3, for instance, recognised the potential threat from a virus spread into his own home from his near-by restaurant, while IT6’s concerns were divided between his own personal dealings and the impacts on his staff:

I am demotivated and demoralised. My father and mother provide moral support, but it is very tough. Even telling the workers to stay home was painful. Two of them have families, and you can imagine what it means to lose a job when you are the one who brings home the salary.

Overall, the results and the associated theoretical underpinnings emerging from categorisations and second order themes from the raw data lend support for the following proposition:

Proposition 1

Key concerns from COVID-19 are fundamentally in the form of substantial financial impacts, and are further aggravated by uncertainty, loss of consumers, the unknown duration of the crisis, and by socioeconomic impacts on employees and on one’s livelihood.

4.2. Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic

Following the approach to theory development stemming from an inductive approach to qualitative research put forward by several authors, including Gioia et al. (2012) and Thomas (2006), Fig. 2 illustrates key coping strategies in response to the pandemic. Again, three main dimensions were revealed, and under these, various second-order themes emanating from the numerous extended survey comments (first-order codes). As many as 34 participants observed more than one way to cope, and 37.8 percent of these recognised undertaking changes, with special focus on generating alternative revenue streams. The same percentage of participants chose a vigilant position, which articulates the preparation for changes in health and safety requirements while their operations had been critically affected. Further comments identified a third group, which was currently inoperative.

Essentially, depending on the structure and model of the business, the self-reliant dimension became apparent, for instance, through the incorporation or strengthening of food delivery and take-away options (e.g., AU4, AU6, AU7, IT5). These basic yet vital strategies are aligned with research that highlights these and other alternatives hospitality and tourism firms are considering (Gössling et al., 2020), some of which correspond to consumer trends during COVID-19 (Baker et al., 2020). The innovative and creative approaches undertaken to try to rethink operations and vulnerabilities in the supply chain alongside harnessing technology (Sharma et al., 2020) to enable delivery of products, highlights the different measures and the complexity in responding to the effects of COVID-19.

The self-reliant dimension was also echoed in other participants’ comments highlighting innovative and creative approaches to generate new business opportunities. AR1, for instance, acknowledged that her winery had just opened a store just days before the pandemic brought footfall and customer traffic to a complete standstill. This opening proved vital in generating cash-flow, and in helping offset substantial losses due to the closure of the winery: “This wine and deli was introduced in a delivery app, managing to maintain the employment and occupation of all permanent tourism staff and part of part-time staff…” In addition, given that no travellers could visit the winery to taste and purchase wines, a pronounced involvement in online sales became strategically vital (AR1): “We reinforced the sales of wine through a web store with free home delivery throughout the country, with special promotions for tourism visitors and frequent customers.” UK2, who produced and sold gin at his own bar and offered food pairings, acknowledged developing new product lines, for instance, different bottle sizes, bundles of beverages, and different price points designed to suit the needs of consumers forced to spend more time at home: “What people are doing at home is at the forefront of our minds now.”

These findings accord with Eggers’s (2020) suggestion that through proactive and innovative postures, firms can also create market opportunities at times of crises. Such postures put forward by Eggers (2020) were also clearly demonstrated in the case of AU6, whose comments convey dramatic and insightful notions of ways in which resilience could be built, even in light of seemingly devastating situations:

The night the government made the announcement (no seated food service), I just cried. I cried and cried and cried some more. I just had no idea what we were going to do… I remember just feeling so lost and uncertain. I then thought: “I am going to go to [business name]; I’m going to make some wholesome home cooked recipes like tuna Mornay, sticky date pudding… and they just flew out the door; in the first few weeks we could hardly keep up. So I thought: “No more crying; this is how I am going to make it through”…

For others, however, the geographic location of the business (distant from consumer traffic or demand points), or the business structure and circumstances (food only for guests, no food-wine offerings, local employees barred from leaving their homes) prevented other participating firms from dynamic reactions, where new business ideas would benefit from prompt implementation.

Hence, while there was a group of participants whose situations precluded them from controlling their destiny, therefore forcing them to adopt a vigilant position, numerous others acknowledged interrupting their operations due to enforced government measures hence, becoming inoperative. These businesses (e.g., AR2, AR3, BO3, GR5, GR6, BO3, IT2, IT3, MA1, MA2, MA3, SP1, UK3) reaffirm the inoperative dimension. For instance, AR4, whose hotel was some three kilometres from a populated area, with lack of a sealed road, thus, with little if any opportunity to generate income: “Our hotel has been closed since 18 March, and our staff members could not come to work due to mandatory quarantine.” Even facing the potential loss of her business, the owner resisted taking drastic decisions: “Until now, nobody in the work team has been made redundant.”

Based upon the results above and manifested in Fig. 2, the following proposition is identified:

Proposition 2

Following COVID-19-related impacts, firm owners and managers typically would adopt the following approaches:

- a)

Active, for instance, improvising their product-service offerings, or exploiting their capabilities to innovate and the convenience of their location,

- b)

Inactive approach, choosing to stay vigilant, where preparations for a new post-pandemic regime are undertaken, or

- c)

Inoperative, where the only choice is to discontinue operations, or stand-by for new protocols allowing a reopening of the business.

Associated with the last point, and in discussing community resilience, Norris et al. (2008) posit that while resilience theory focuses on adaptive capacities, “the fundamental role of the stressor” (p. 146) should not be overlooked. Norris et al.’s (2008) key point here highlights the severity and magnitude of some devastating events, “from which even the most resourceful individuals or communities would struggle mightily to recover” (p. 146).

4.3. Changes-adjustments to day-to-day activities

Overall, 60 percent of participants recognised making changes or adjustments given the pandemic, while approximately one-third was concerned about compliance of health and safety measures, as well as standing by, waiting for new protocols to be released or announced by government. Thus, the numerous comments (first-order codes), subsequently organised into second-order (theory-centric) themes, are, as was the case of previous questions (Figs. 1, 2) assembled into a ‘data structure’ (Gioia et al., 2012). These themes are then manifested through the following three dimensions, namely: work-based adjustments, adjusting to compliance, and fringe-detachment:

First, the work-based adjustments dimension extends from the business dimension, further emphasising participants’ responses to the initial effects of the pandemic in strategic ways, implementing vital changes in business practices. In some cases, the state of crisis represented a persuasive force in operationalising changes. For instance, alongside forceful changes working from home through online platforms, also considered by other participants (AR3, GR7, IT7, SP2, SP3), AR7) brought unintended positive effects, in that new changes facilitating payment to suppliers online, as opposed to having people visit the business regularly to cash checks. Partly aligned with Eggers’s (2020) premises, for UK2, making work-based adjustments opened the door to opportunities and in addition led to growth: “We have not had time in the past to invest in the website so this has been a good thing for us to do and will be a permanent activity - possibly employing someone to do this.” AU4’s and SP2’s remarks among others demonstrate an entrepreneurial spirit. Rather than being subdued by the crisis, the business bounced back with creative ideas:

AU4: We changed our menu as no one else was doing Mexican food. I was thinking we are not going to do well; there are just so many other restaurants doing the same thing… It has really surprised me.

SP2: For obvious reasons, wine tourism is non-existent right, which is why we have transformed the tasting room into a kind of recording studio. From here, we can carry out online and direct Instagram meetings that clients and loyal customers requested of me.

For others, changes were more exhaustive and included several business areas. In fact, apart from new ways of acquiring supplies, UK3 admitted having to find ways “to convince existing and new customers that we will maintain high standards, find a way of how to deliver our products, buy some new equipment to maintain the temperature of the food until its delivery…”

Second, the adjusting to compliance dimension underscores a group of participants’ cautious approach, arguably as the result of the prevailing circumstances preventing them from running their businesses. Thus, the focus was predominantly on compliance with health and safety requirements and awaiting on further decisions regarding future protocols associated with these aspects. Selected comments such as GR5’s illuminated the extent to necessary adjustments: If we are allowed to open the business again, we will need to prioritise guest’s safety… we will require different communication approaches during check-in and will need to introduce changes at restaurant and bar…to comply with new requirements.

Third, the fringe-detachment dimension illustrates that some participants were also generating ideas, gathering information, as well as reflecting on the future of their operations, and in some cases changing their lifestyle as a result of existing restrictions. The following comments demonstrate this dimension:

IT1: We concentrated mainly on the design of improvements of our multifunctional company. We also took the opportunity to participate in distance learning courses and to spend more time studying and reading.

IT4: After coming back from a long day at work, I could not see my two kids because we sent them with their grandparents… I did not care about the business…I care for my family and what will happen in the future…

As with 33 other participants, IT3 identified more than one way of making changes and adjustments, in her case, with contrasting outcomes. While the participant was becoming used to the new health and safety measures, with staff wearing the required masks and gloves, she also appreciated how “During the lockdown we spent a lot of time with the family, which hadn't happened for a long time…”

Overall, the manifested second-order themes (Fig. 3) complemented by the following comments lead to the formulation of the following proposition:

Proposition 3

Changes and adjustments among hospitality operators as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic are primarily manifested through ways in which day-to-day activities, tasks or routines are undertaken, coupled with increasing awareness and knowledge about health and safety compliance, and attention to new health and safety protocols.

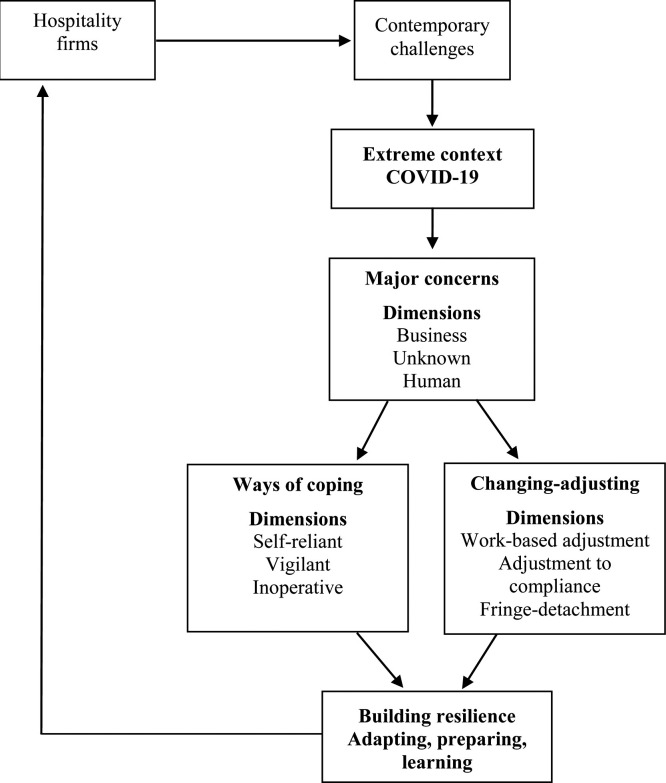

4.4. Proposed consolidated framework

By combining the underpinnings resulting from the assemble of codes, themes and dimensions into a data structure (Gioia et al., 2012) and developed in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, the study also proposes a consolidated framework (Fig. 4 ). At the core of contemporary challenges is the extreme context (Hannah et al., 2009) manifested through the COVID-19 pandemic, where the initial impacts lead to key concerns among owners-managers of hospitality businesses. These initial impacts are highlighted through the business, the unknown, and the human dimensions. From their main concerns, the study theorises two ways of potentially building resilience, notably ways of coping and ways of changing and adjusting. The first underscores the role of being ‘self-reliant’, taking the initiative to respond to the crisis, and the ‘vigilant’ seeks to bide time and cautiously prepare for next stages (end of lockdown and a new regime of compliance). Further, the ‘inoperative’, despite its negative undertone, refers to those entrepreneurs who, because of specific negative consequences and lack of structure to action an alternative plan, were forced to discontinue the businesses, or, for instance, are waiting for the lockdown to be lifted and resume operations. Finally, in terms of changing-adjusting, some of the coping strategies are further reinforced, with work-based adjustment illustrating a proactive approach. Another dimension, adjustment to compliance, suggests changes in the way the firm operates, again, focusing on new regulations, while the fringe-detachment dimension underlines a reflective approach regarding the future of the business, as well as thoughts regarding one’s lifestyle changes.

Fig. 4.

Proposed theoretical framework – Understanding concerns, coping, adjusting.

5. Conclusions

Drawing on an international sample of 45 hospitality firms, the present exploratory study addressed two key objectives associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and the hospitality industry, thus, contributing to existing resilience literature. First, the study examined owners’ and managers’ perceived main concerns, ways of coping, and changes-adjustments as a result of this extreme context (Hannah et al., 2009). In doing so, the study also helped narrow an existing knowledge gap. For example, Conz et al. (2017) acknowledge that “the resilience of SMEs is under investigated” (p. 187), including perspectives considering which strategies can influence the resilience of these firms. With regard to the second objective, following the chosen inductive paradigm, the identified first-order codes, organised into second-order themes, and subsequently into theoretical dimensions led to the development of several theoretical frameworks. Among other insights, these frameworks illustrate how firm owners and managers act and react in light of an event of such magnitude, thereby revealing valuable strategic steps.

5.1. Implications

Various implications are highlighted in this study’s findings. From a conceptual and theoretical standpoint, while Fig. 1 identifies first-order codes and second-order themes, leading to ‘overarching theoretical dimensions’ (Gioia et al., 2012) related to concerns from COVID-19, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 highlight aspects of resilient entrepreneurs and firms. Further, in revealing nine different dimensions, with several (business, self-reliant, word-based-adjustment) suggesting a sense of urgency and control of one’s destiny, the proposed frameworks provide different paths that businesses involved in the hospitality and tourism delivery can consider in seeking to manage this unprecedented crisis. More specifically, the figures and open-ended comments accord with Norris et al.’s (2008) premises, in that they illustrate processes manifested through activities and adaptive capacities that allowed participants and their firms to embark on a positive trajectory to function and therefore adapt after this devastating event. Thus, together, these frameworks enable insight into the adaptability and coping ability within the entrepreneurial mindset in the aftermath of such devastating circumstances.

From a more holistic viewpoint, the frameworks also further understanding concerning the entrepreneurial psyche and resilience in what will be noted as one of the most challenging times in modern history. Another implication emerges, in that the conceptual basis of these frameworks, coupled with their practical substance emanating from business and life situations experienced by business owners-managers, could illuminate other research endeavours, where coping, adapting and overall building resilience are key aims. Rivera (2020), for instance, perceives an imperative need in post recovery research in the areas of planning and crisis management. The value of the theoretical foundation put forward in this research points to vital aspects and factors that contribute to crisis management, planning, and the gradual addressing of a unique event. Finally, although the value of these frameworks is directly geared towards business owners-managers of hospitality, and by extension tourism businesses and industry, they also encompass fundamental value to other stakeholders that, as is the case of suppliers or chambers of commerce, strive for a sense of direction and guidance while developing a future course of action. The framework and the emergent changes as part of the effect of Covid-19 have, in essence, revealed a ‘new normal’ for businesses and industry to consider.

Thus, by identifying key adaptive measures among entrepreneurs, the research also has practical implications, offering business-related value to practitioners operating in an extreme context (Hannah et al., 2009). First, aligned with previous observations (Baker et al., 2020; Gössling et al., 2020), the findings illustrate ways in which participants acted upon severe restrictions and challenges, quickly reverting to practical and pragmatic means to maintain vital cash-flow and safeguard their livelihoods. Second, many participants engaged in making adjustments and changes, prioritising activities to alleviate current dilemmas whilst identifying practical ways to revamp and help their businesses become more adaptive. No matter how futile, these actions suggest opportunities for entrepreneurs to be innovative and alter their business offerings to survive. Leaving aside the futility and potential for demise allows entrepreneurs to realise the ability to adapt and identify suitable options. This display of resilience is true even during major catastrophic events.

Further, many businesses became inoperative, and the focus shifted on compliance and future protocols, as well as reflecting upon the future of the business. These cases illustrate a dire need for external support that needs to be channelled to reach the recipients urgently to prevent a domino effect. In this scenario, employees lose vital income, suppliers become exposed given the impossibility of relocating supplies or receiving payments, and other businesses that rely on employees and suppliers also become severely affected. Thus, while the need for government support is a common observation, failure to have contingency plans that include prompt economic relief, especially in case of a resurgence in this or other health concerns, could have extremely painful consequences for the long-term recovery of the hospitality, tourism, and other industries.

5.2. Limitations and future research

Despite its numerous revealed insights, the present research is not free of limitations. The study has focused mainly upon small hospitality firms with a sample size of 45 businesses. While the results provide useful outcomes, its generalisability and application to a wider context needs to be carefully considered. However, these limitations could be addressed in future studies, which consequently could broaden the scope to elicit data from larger hospitality organisations, potentially gathering larger numbers, and including other nations where the hospitality and tourism industries play a key role, for instance, in employment creation.

Another avenue of future research could consider the links between the hospitality industry and medical science. Indeed, Wen et al. (2020) highlight the relevance of bringing together health-medical experts and professionals from both the hospitality and tourism industries in collaborative research projects. These efforts could be insightful and potentially valuable, particularly in protecting the overall well-being of key stakeholders, including travellers and staff (Wen et al., 2020). Based upon these notions, research could seek to identify how hospitality and tourism operators could best collaborate with health-medical experts for mutual benefit, whether through individual visits, or through workshops and other events to raise awareness and disseminate knowledge. This knowledge could help many firms to prepare in the eventuality of new health-related cases, and ways to act promptly to avoid new lockdowns, with potentially devastating consequences for businesses, employees, clients-visitors, and entire economies.

Finally, future research could test the various theoretical frameworks proposed in this exploratory study, confirming their overall value, or potentially complementing them with additional dimensions that might be uncovered.

References

- Argentinian Government . 2018. Nuevas categorías para ser PyME. Available at: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/noticias/nuevas-categorias-para-ser-pyme. [Google Scholar]

- Ates A., Bititci U. Change process: a key enabler for building resilient SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011;49(18):5601–5618. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2002. Small Business in Australia, 2001. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1321.0. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.R., Farrokhnia R.A., Meyer S., Pagel M., Yannelis C. 2020. How Does Household Spending Respond to an Epidemic? Consumption During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Working Paper. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w26949.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:248–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In: Locke E.A., editor. The Blackwell Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behaviour. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2000. pp. 120–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A., Adams N.E. Analysis of self-efficacy theory of behavioral change. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1977;1(4):287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Barczak G. Publishing qualitative versus quantitative research. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. 2015;5(32) 658-658. [Google Scholar]

- Bartik A.W., Bertrand M., Cullen Z.B., Glaeser E.L., Luca M., Stanton C.T. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2020. How Are Small Businesses Adjusting to COVID-19? Early Evidence from a Survey. Working Paper 26989. [Google Scholar]

- Baum T., Hai N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 2020;32(7):2397–2407. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley P., Jackson K. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications Ltd.; London, UK: 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis with Vivo. [Google Scholar]

- Branicki L.J., Sullivan-Taylor B., Livschitz S.R. How entrepreneurial resilience generates resilient SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018;24(7):1244–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Orchiston C., Johnston D. Exploring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: a systematic review of literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017;22:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Orchiston C., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Johnston D. An integrative framework for investigating disaster resilience within the hotel sector. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018;36:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brown N.A., Rovins J.E., Feldmann-Jensen S., Orchiston C., Johnston D. Measuring disaster resilience within the hotel sector: an exploratory survey of Wellington and Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand hotel staff and managers. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019;33:108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Conz E., Denicolai S., Zucchella A. The resilience strategies of SMEs in mature clusters. J. Enterprising Commun. People Places Glob. Econ. 2017;11(1):186–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dobie S., Schneider J., Kesgin M., Lagiewski R. Hotels as critical hubs for destination disaster resilience: an analysis of hotel corporations’ CSR activities supporting disaster relief and resilience. Infrastructures. 2018;3(4):46. [Google Scholar]

- Durán M.Á. Deutsche Gesellschaft; San Salvador, El Salvador: 2009. Manual de la micro, pequeña y mediana empresa. Una contribución a la mejora de los sistemas de información y el desarrollo de las políticas públicas. Available at: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/2022/1/Manual_Micro_Pequenha_Mediana_Empresa_es.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Eggers F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020;116:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2003. What is an SME? Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/sme-definition_en. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament . 2020. Covid-19 and the Tourism Sector. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2020/649368/EPRS_ATA(2020)649368_EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gatto F. Desafíos competitivos del Mercosur a las pequeñas y medianas empresas industriales. Rev. Cepal. 1999;68:61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia D.A., Corley K.G., Hamilton A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods. 2012;16(1):15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gist M.E. Self-efficacy: implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987;12(3):472–485. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020 forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Gruman J.A., Chhinzer N., Smith G.W. An exploratory study of the level of disaster preparedness in the Canadian hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011;12(1):43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hall C.M., Scott D., Gössling S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020;22(3):577–598. [Google Scholar]

- Hallak R., Assaker G., O’Connor P., Lee C. Firm performance in the upscale restaurant sector: the effects of resilience, creative self-efficacy, innovation and industry experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018;40:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah S.T., Uhl-Bien M., Avolio B.J., Cavarretta F.L. A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. Leadersh. Q. 2009;20(6):897–919. [Google Scholar]

- Herbane B. Rethinking organizational resilience and strategic renewal in SMEs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019;31(5–6):476–495. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuckertz A., Brändle L., Gaudig A., Hinderer S., Reyes C.A.M., Prochotta A., Steinbrink K.M., Berger E.S. Startups in times of crisis–a rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna Z., Williams K.H., Childers C. An assessment of resilience: disaster management and recovery for greater New Orleans’ hotels. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2012;11(3):210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha M., Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus and COVID-19 pandemic: a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris F.H., Stevens S.P., Pfefferbaum B., Wyche K.F., Pfefferbaum R.L. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2008;41(1–2):127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. OECD Interim Economic Assessment - Coronavirus: The World Economy at Risk. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/berlin/publikationen/Interim-Economic-Assessment-2-March-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Orchiston C. Tourism business preparedness, resilience and disaster planning in a region of high seismic risk: the case of the Southern Alps, New Zealand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013;16(5):477–494. [Google Scholar]

- Pal R., Torstensson H., Mattila H. Antecedents of organizational resilience in economic crises—an empirical study of Swedish textile and clothing SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014;147:410–428. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M.Q. 4th ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2015. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera M.A. Hitting the reset button for hospitality research in times of crisis: Covid19 and beyond. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020;87 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainaghi R., De Carlo M., d’Angella F. Development of a tourism destination: exploring the role of destination capabilities. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019;43(4):517–543. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Adhikary A., Borah S.B. Covid-19’s impact on supply chain decisions: strategic insights for NASDAQ 100 firms using Twitter data. J. Bus. Res. 2020;117:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydnor-Bousso S., Stafford K., Tews M., Adler H. Toward a resilience model for the hospitality & tourism industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2011;10(2):195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D.R. A general inductive approach for analyszing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Tibay V., Miller J., Chang-Richards A.Y., Egbelakin T., Seville E., Wilkinson S. Business resilience: a study of Auckland hospitality sector. Procedia Eng. 2018;212:1217–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney P., Farmer S.M. Creative self-efficacy: its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002;45(6):1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Wen J., Wang W., Kozak M., Liu X., Hou H. Many brains are better than one: the importance of interdisciplinary studies on COVID-19 in and beyond tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020 forthcoming. [Google Scholar]