Abstract

Amyloid-β (Aβ) is an intrinsically disordered peptide thought to play an important role in Alzheimer’s Disease. It has been the target of most AD therapeutic efforts, which have repeatedly failed in clinical trials. A more predominant peptidic fragment, formed through alternative processing of the Amyloid Precursor Protein, is the p3 peptide. p3 has received little attention, which is possibly due to the prevailing view in the AD field that it is “non-amyloidogenic”. By probing the self-assembly of this peptide, we found that p3 aggregates to form oligomers and fibrils, and when compared with Aβ, displays enhanced aggregation rates. Our findings highlight the solubilizing effect of the N-terminus of Aβ, and the favorable formation of structures formed through C-terminal hydrophobic peptide interfaces. Our findings suggest a reevaluation of the current therapeutic approaches targeting only the β-secretase pathway of AD, given that the α- secretase pathway is also amyloidogenic.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, amyloid-β, amyloid-α, oligomer, fibril, aggregation

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a debilitating neurological disease characterized by amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tau tangles. It currently affects almost 50 million people worldwide.1 Although amyloid plaques may contain up to 900 unique proteins, with approximately 200 found consistently,2,3 the target of most therapeutic efforts to date has been the Amyloid-β peptide (Aβ).4,5 Aβ has been the subject of thousands of publications annually since 2000, a figure that is exponentially rising (Fig. S1). Yet, in 2020, all Phase III drugs designed to reduce Aβ production or aggregation have failed,6 and we are far from an effective treatment for AD.5–9 Thus, it is critical to investigate the contribution of other plaque-associated peptides to amyloid deposition in the brain.

In light of recent findings that fragments of Aβ exhibit enhanced aggregation propensity,10,11 we sought to understand the predominant cleavage product of the Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP),12 cleaved by α- rather than β- secretase. This peptide, termed p3, has received remarkably little attention and it is largely regarded as benign. However, its biophysical and biological properties remain unclear and inconsistent, as discussed in our recent review13 and summarized in Table S1. Some have described p3 as neuroprotective,14 while others have demonstrated that p3 exhibits significant cytotoxicity.15,16 Whereas p3 is often referred to as soluble and “non-amyloidogenic”,17–22 several studies found that p3 formed “amorphous aggregates” and “lattice-like” networks,19,23 and, possibly, amyloid fibrils.24,25 One study, conducted by Vandersteen et. al.25 revealed what were described as fibrillar fragments, shorter and dissimilar to those formed by Aβ. Despite the aforementioned studies revealing fibrillar-like morphologies for p3, potentially indicative of amyloidogenicity, the field still recognizes p3 production as an alternative neuroprotective, “non-amyloidogenic” pathway of APP.17,19–22 To deconvolute these conflicting claims, we sought out to investigate the aggregation propensity of p3. We hypothesized, based on the hydrophobicity and large regions of predicted amyloidogenicity,13 that p3 could aggregate to form oligomers and fibrils.

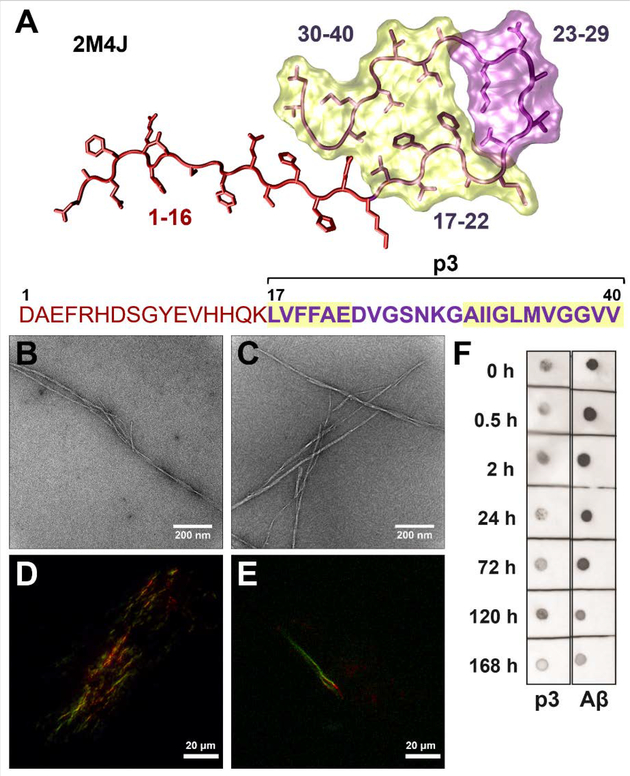

To probe our hypothesis, that despite lacking the first 16 amino acids, p3 shares amyloidogenic properties with Aβ, p3 and Aβ (Fig. 1A) were synthesized and purified using our published protocols26 (Fig. S2–S3). To evaluate fibrillogenicity, p3 was incubated under fibril-forming conditions and compared alongside Aβ. TEM analysis of p3 fibrils (Fig. 1B; S9A–B) revealed long, twisted fibrillar structures that closely resemble the fibrils formed by Aβ (Fig 1C). For both p3 and Aβ, the resultant fibril morphologies bear semblance to published quiescently-formed Aβ fibrils.27 Thus, the absence of the hydrophilic, disordered N-terminus did not preclude fibril formation in p3, contrary to the previous claims that p3 is “non-amyloidogenic”.18,19 In addition, p3 fibrils exhibited characteristic green birefringence typical for cross-β-sheet amyloid structures,28,29 under polarized light upon incubation with Congo Red (CR) (Fig. 1D), again indistinguishable from Aβ (Fig. 1E). The presence of β-sheet-rich structures formed by p3 revealed by the CR assay are in agreement with the circular dichroism results obtained by Ali et. al.30

Figure 1. Fibrillogenicity of p3 compared with Aβ.

A) Fibril structure35 and sequence of Aβ(1–40), with p3(17–40) indicated in purple. Highlighted regions (17–22 and 30–40) indicate the amyloidogenic regions of Aβ, calculated by AGGRESCAN.13 TEM images of fibrillar B) p3 and C) Aβ. Polarized light microscopy images of CR stained D) p3 and E) Aβ fibrils. F) Dot blots stained for OC binding for Aβ and p3. All peptide samples were prepared at 20 μM and incubated for 7 days at 37 °C in PBS (pH 7.4).

Our results agree with the findings of Sawaya et. al. that large hydrophobic residue patches frequently associate to form “steric zippers”.31 A hydrophobic steric zipper is plausible in the case of p3 given that the two amyloidogenic, hydrophobic patches of Aβ (LVFFAE and AIIGLMVGGVV)13 are also found in p3 (Fig. 1A). To further investigate if fibrillar Aβ and p3 have conformational similarities, the OC antibody, which recognizes conformation-specific epitopes of amyloid fibrils,32 was employed (Fig. 1F). The dot blots reveal OC binding for both p3 and Aβ across all timepoints, confirming the presence of conformational similarities in the fibril structures for both peptides, again highlighting the importance of the hydrophobic C-terminal regions for fibril formation.31 Together, these findings of shared fibril morphology with Aβ, CR birefringence, and OC-binding, establish that p3 is amyloidogenic as defined by the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis.33,34

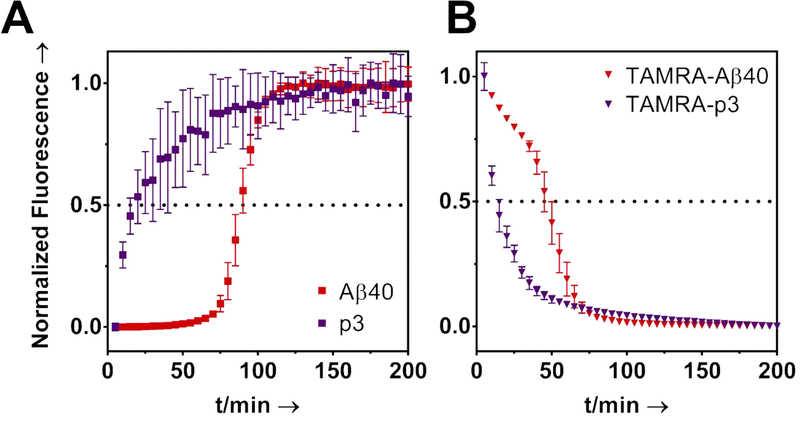

We next studied fibril formation kinetics of p3 via the Thioflavin T (ThT) and TAMRA-quenching assays.36 The ThT assay (Fig. 2A) revealed that the fibrilization of p3 was significantly more rapid than for Aβ. The p3 kinetic profile was absent of a characteristic sigmoidal growth profile beginning with a “lag phase”, that is typically seen for Aβ. This indicates that the nucleation phase of the fibril formation mechanism was expedited for p3. Moreover, a ThT-monitored seeding assay revealed that Aβ fibrilization can be enhanced by seeding of pre-formed p3 fibrils (Fig. S10).

Figure 2. Kinetics of Fibril Formation.

A) ThT (20μM) monitored aggregation kinetics of Aβ and p3. B) TAMRA quenching assay. Peptides were prepared at 20 μM and incubated at 37 °C in PBS (pH 7.4) with continuous shaking. Each data point is an average of four replicates with error bars representing standard deviation.

To validate the kinetic trends seen in the ThT assays, TAMRA dye was conjugated to the N-termini of p3 and Aβ (Fig. S6–S7), and the fluorescence signal suppression, indicative of aggregation,36 was monitored. As shown in Fig. 2B, TAMRA-p3 fluorescence decayed more rapidly than TAMRA-Aβ, further revealing that p3 forms fibrils more rapidly than Aβ. The ion-rich 1–16 region of Aβ therefore appears to provide a solubilizing function for Aβ, which attenuates amyloid fibril formation. This may also explain why p3 is a major component of preamyloid plaques found in the brains of those with Down Syndrome.19 Fibril formation of TAMRA-p3 was confirmed with TEM (Fig. S8–S9). Together, these results indicate that p3 may play an important role in amyloid deposition in the brains of those with AD.

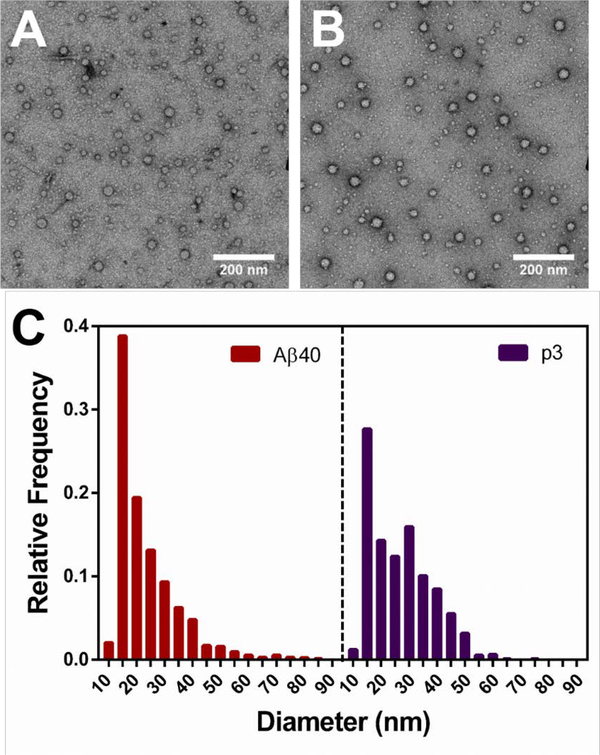

Evidence is growing that the toxicity of Aβ is not from the accumulation of insoluble fibrils, but rather from the soluble oligomeric intermediates.37 Oligomers have been shown to disrupt neuronal function,38 long-term potentiation,39 neuronal microRNA expression,40 and memory.41,42 Oligomers vary in size and shape and are difficult to characterize given their transient nature. Following the trapping protocol by Ahmed et. al.,43 we trapped and imaged p3 oligomers, which are indistinguishable from those shown in TEM images of Aβ published by Ahmed. et. al.43 The TEM images displayed in Fig. 3A–B (Fig. S11) reveal round particles ranging from 10–85 nm in diameter for both p3 and Aβ. No elongated, fibrillar species were identified in the oligomeric TEM images, as reflected in the histograms shown in Fig. 3C. The average particle diameter for p3 was determined to be 26.6 ± 11.2 which is within error of the value calculated for Aβ, 23.4 ± 11.5 nm (Fig. 3C). The histograms shown in Fig. 3C reveal very similar particle size distributions for both peptides. However, the histogram for Aβ exhibits some tailing, representative of larger structures (60–100 nm) not prevalently seen for p3. The formation of large non-spherical, elongated structures seen for Aβ but not p3, may be due to micelle formation, promoted by the amiphipathic, surfactant-like build of Aβ,44 a property not shared with p3 (Fig. 1A). To the best of our knowledge, these are the first TEM images of oligomers formed by p3, refuting the previous claim that p3 does not form oligomers.45 Our findings that p3 forms oligomers similar to those formed by Aβ agree with the MD simulations conducted by Miller et. al. indicating that p3 oligomers can form both parallel and antiparallel β-sheets.46 Moreover, since several studies have demonstrated cellular toxicity for both monomeric and fibrillar p3,15,16,23,47 we probed the toxicity of oligomeric p3 (Fig. S12). We found that at 50 μM, p3 reduced SH-SY5Y cell viability to approximately 80%, in comparison to 50% for Aβ-treated cells (Fig. S12). We attribute the higher viability of p3-treated cells to the rapidity of p3 fibrilization, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 3. Oligomer Characterization.

TEM images of 20 μM A) Aβ and B) p3 incubated at 4°C in PBS (pH 7.4) for 6h. C) Histograms displaying size distribution of oligomers formed by Aβ and p3 calculated from A-B and Fig. S11.

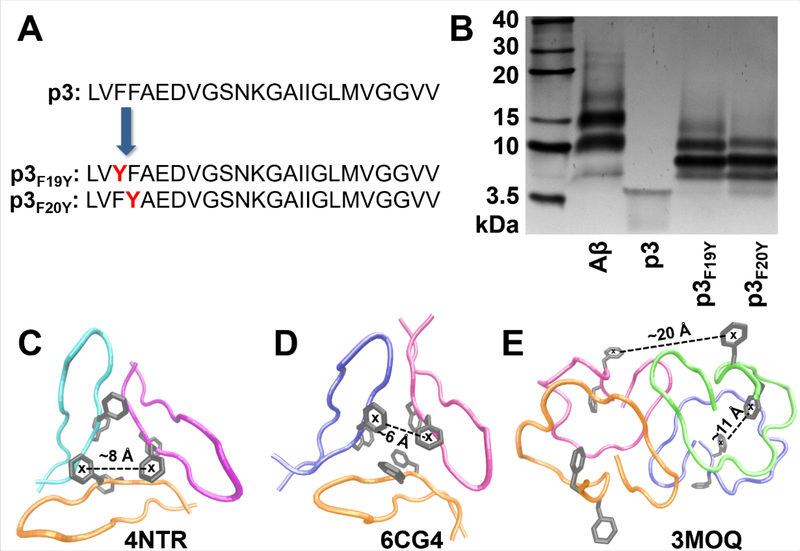

To further characterize early stages of self-assembly of p3, photo-induced crosslinking48 was utilized to provide a snapshot of the short-lived, metastable oligomers. Two modified variants of p3 were synthesized given that tyrosine is required for crosslinking49 (Fig. 4A): p3F19Y, p3F20Y. The SDS-PAGE gel shown in Fig. 4B reveals monomeric, dimeric, trimeric and tetrameric oligomers resulting from covalent cross-linking for both p3F19Y and p3F20Y. Aβ also formed similar assembly sizes in addition to faint signals corresponding to higher order structures (20–30 kDa), which may be related to the presence of larger oligomers formed by Aβ but not p3, as seen in TEM (Fig. 3; S11). The presence of low-N oligomers identified with TEM and SDS-PAGE demonstrate that p3 can form transient intermediates broadly similar in size and shape as Aβ. These findings are important in the context of AD because cellular toxicity of Aβ oligomers has been attributed to an excess of hydrophobic surface exposure of oligomers in cell membranes.50 Given that p3 is almost entirely hydrophobic (Fig. 1A), p3 oligomers could potentially play an important role in amyloid-related neurotoxicity.

Figure 4. Oligomer Characterization.

A) Sequences of p3 peptides with Phe → Tyr substitutions. B) SDS-PAGE gel of crosslinked samples of Aβ, p3, p3F19Y, p3F20Y (20 μM). Control, non-crosslinked samples are shown in Fig. S13. Crystal structures displaying possible trimeric (C51,D52) and tetrameric (E)53 assemblies of p3 peptidic fragments, with representative centroid-to-centroid distances between phenylalanines from neighboring units indicated.

ThT kinetic curves for both p3F19Y and p3F20Y are shown in Fig. S14, indicating that tyrosine substitution did not prevent fibril formation. Interestingly, the kinetic profile for p3F20Y closely matched that of p3, while p3F19Y exhibited a slightly attenuated onset of aggregation. This may indicate a favorable interaction between F19 and another residue, reinforced by the discovery that a F19P mutation abolishes Aβ aggregation.54 Moreover, our findings are supported by Bitan et. al. showing that truncations of residues 1–9 of Aβ do not inhibit oligomer formation.49 Aβ also formed similar assembly sizes in addition to faint signals corresponding to high-N structures (20–30 kDa).

Furthermore, the enhanced staining for trimers and tetramers for p3 shown in Fig. 4B may reveal initial steps in the mechanism of p3 aggregation. Crystal structures of similar species are shown in Fig. 4C–E,51–53 indicating possible structures of the prominent species shown in Fig. 4B.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the “non-amyloidogenic” p3 peptide, in fact does exhibit substantial amyloidogenic properties. Given this, and its similarity to Aβ, we propose to rename p3 to Amyloid-α (Aα). Our results revealed OC-positive, CR birefringent, p3 fibrils that formed more rapidly than Aβ. We also found that, contrary to previous literature,45 p3 aggregated to form intermediate oligomers, that share a similar size distribution with Aβ. Overall, this work suggests that p3 may not be as innocuous as previously suggested, and further analysis is needed to understand the role of p3 in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Methods

Additional experimental methods can be found in the Supporting Information.

Peptide Synthesis

All peptides were synthesized by SPPS using Fmoc chemistry, following our previously published protocols55 on Tentagel® S PHB resin (Rapp Polymere GmbH, cat no. RA1327).

Fibril growth

Lyophilized peptide (Aβ40 or p3) was dissolved in 20 mM NaOH and sonicated for 30 s, then diluted to 20 μM in PBS. The samples were incubated either (1) at 37 °C for 24 hours with mild agitation, or (2) at 37 °C quiescently for 7 days. For TEM imaging, 3 μL of sample aliquots were spotted onto freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated electron microscopy grids (Ted Pella, Catalog No. 01701-F). The grids were rinsed with milliQ water after 1 min incubation, followed by staining with 30 μL 1% uranyl acetate.

Congo Red

Since CR crystals can exhibit false-positive birefringence, a protocol from Nakka et. al.56 was adapted. Either Aβ40 or p3 fibrils were grown quiescently as described above at 20 μM. Fibrils were centrifuged at 14000 g for 15 min and washed with MilliQ H2O x2. 5 μL of the CR stock solution (7 mg of CR in 1 mL MilliQ H2O) was added to 1 mL of MilliQ H2O and then added to the pelleted peptides. The samples were incubated for 1 h with mild agitation and centrifuged at 14000 g for 15 min and washed with MilliQ H2O x2. 30 μL were added to glass slides and air-dried overnight. Images were collected on a Leica Epifluorescence widefield microscope, with a polarizer.

Dot blot assay

Aβ40 or p3 fibrils (20 μM) were prepared as described above and kept at 37 °C. At each timepoint over the course of 7 days, 2 μL of sample was spotted on nitrocellulose. After the blots dried, they were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 h at 25 °C. The samples were then washed with TBST for 5 min x3, and then incubated with OC antibody (1:1000 in 5% non-fat milk in TBST) overnight at 4 °C, followed by washing with TBST for 5 min x3. The membrane was then incubated with the secondary antibody (1:10,000 in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST) for 1 h at 25 °C, and washed with TBST for 5 min x3 and then developed with the Opti-4CN Substrate kit (Bio-Rad, cat no. 1708235).

Oligomer Growth and Imaging

To trap the intermediate oligomers, lyophilized Aβ40 or p3 was dissolved in cold 20mM NaOH and sonicated in an ice bath for 30 s. Samples were diluted to either 20 μM in PBS and incubated at 4 °C for 6 h without agitation. TEM samples were prepared and imaged as described above.

ThT Assay and TAMRA Quenching Assays

ThT assay and TAMRA quenching were conducted as described previously.57,58

Photochemically induced crosslinking of peptides

4 μL of 1 mM [Ru(bipy)3]2+ and 4 μL of 20 mM ammonium persulfate were added to 32 μL aliquots of 20 μM Aβ40, p3, p3F19Y and p3F20Y in PBS. The samples were irradiated for 1.2 s with white light using our previously described setup.55 Following irradiation, the samples were immediately quenched with 40 μL of loading buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis (12% tris-tricine polyacrylamide) at 100 V for 2 h. The gels were developed by silver staining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

J.A.R. thanks UC Santa Cruz for the flexible start-up funds, and NIH for funding (R21AG058074). A.J.K. thanks the NIH for funding (F31AG066377). J.A.R. and A.J.K. also thank Dr. James Nowick for helpful conversations and Kareem Bdeir for his help with peptide purification.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

General experimental procedures; histogram of Aβ publication trends; sample characterization and purity; additional TEM images; ThT kinetics; cellular viability; SDS-PAGE gel of non-crosslinked peptides.

References

- (1).Prince M; Wilmo A; Guerchet M; Ali G-C; Wu Y-T; Prina M World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Duong DM; Peng J; Rees HD; Wang J; Liao L; Levey AI; Gearing M; Lah JJ; Cheng D; Losik TG Proteomic Characterization of Postmortem Amyloid Plaques Isolated by Laser Capture Microdissection. J Biol Chem 2004, 279 (35), 37061–37068. 10.1074/jbc.m403672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Drummond E; Nayak S; Faustin A; Pires G; Hickman RA; Askenazi M; Cohen M; Haldiman T; Kim C; Han X; Shao Y; Safar JG; Ueberheide B; Wisniewski T Proteomic Differences in Amyloid Plaques in Rapidly Progressive and Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol 2017, 133 (6), 933–954. 10.1007/s00401-017-1691-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Cummings J; Lee G; Ritter A; Zhong K Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Development Pipeline: 2018. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv 2018, 4, 195–214. 10.1016/j.trci.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Knopman DS Lowering of Amyloid-Beta by β-Secretase Inhibitors — Some Informative Failures. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, 11–13. 10.1056/NEJMe1903193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Karran E; Strooper B De. The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis: Are We Poised for Success or Failure? J Neurochem 2016, 139 (2), 237–252. 10.1111/jnc.13632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Egan MF; Kost J; Voss T; Mukai Y; Aisen PS; Cummings JL; Tariot PN; Vellas B; Van Dyck CH; Boada M; Zhang Y; Li W; Furtek C; Mahoney E; Mozley LH; Mo Y; Sur C; Michelson D Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 380 (15), 1408–1420. 10.1056/NEJMoa1812840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Egan MF; Kost J; Tariot PN; Aisen PS; Cummings JL; Vellas B; Sur C; Mukai Y; Voss T; Furtek C; Mahoney E; Mozley LH; Vandenberghe R; Mo Y; Michelson D Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2018, 378 (18), 1691–1703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Henley D; Raghavan N; Sperling R; Aisen P; Raman R; Romano G Preliminary Results of a Trial of Atabecestat in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 380 (15), 1483–1485. 10.1056/NEJMc1210001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wulff M; Baumann M; Thümmler A; Yadav JK; Heinrich L; Knüpfer U; Schlenzig D; Schierhorn A; Rahfeld JU; Horn U; Balbach J; Demuth HU; Fändrich M Enhanced Fibril Fragmentation of N-Terminally Truncated and Pyroglutamyl-Modified Aβ Peptides. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2016, 55 (16), 5081–5084. 10.1002/anie.201511099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Barritt JD; Younan ND; Viles JH N-Terminally Truncated Amyloid-β(11–40/42) Cofibrillizes with Its Full-Length Counterpart: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2017, 56 (33), 9816–9819. 10.1002/anie.201704618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Moghekar A; Rao S; Li M; Ruben D; Mammen A; Tang X; O’Brien RJ Large Quantities of Aβ Peptide Are Constitutively Released during Amyloid Precursor Protein Metabolism in Vivo and in Vitro. J Biol Chem 2011, 286 (18), 15989–15997. 10.1074/jbc.M110.191262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kuhn AJ; Raskatov JA Is the P3 (Aβ17–40, Aβ17–42) Peptide Relevant to the Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease? J Alzheimer’s Dis 2020, 74 (1), 43–53. 10.3233/JAD-191201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Han W; Ji T; Mei B; Su J Peptide P3 May Play a Neuroprotective Role in the Brain. Med Hypotheses 2011, 76 (4), 543–546. 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wei W; Norton DD; Wang X; Kusiak JW Aβ 17–42 in Alzheimer’s Disease Activates JNK and Caspase-8 Leading to Neuronal Apoptosis. Brain 2002, 125, 2036–2043. 10.1093/brain/awf205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jang H; Arce FT; Ramachandran S; Capone R; Azimova R; Kagan BL; Nussinov R; Lal R Truncated β-Amyloid Peptide Channels Provide an Alternative Mechanism for Alzheimer’s Disease and Down Syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2010, 107 (14), 6538–6543. 10.1073/pnas.0914251107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Querfurth, Henry W; LaFerla FM Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 2010, 3628 (4), 329–344. 10.1136/bmj.b158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Naslund J; Jensen M; Tjernberg LO; Thyberg J; Terenius L; Nordstedt C The Metabolic Pathway Generating P3, an Aβ Peptide Fragment, Is Probably Non-Amyloidogenic. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994, 204 (2), 780–787. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lalowski M; Golabek A; Lemere CA; Selkoe DJ; Wisniewski HM; Beavis RC; Frangione B; Wisniewski T The “Nonamyloidogenic” P3 Fragment (Amyloid Beta 17–42) Is a Major Constituent of Down’s Syndrome Cerebellar Preamyloid. J Biol Chem 1996, 271 (52), 33623–33631. 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Pinheiro L; Faustino C Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Amyloid-Beta in Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2019, pp 418–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Coronel R; Bernabeu-Zornoza A; Palmer C; Muñiz-Moreno M; Zambrano A; Cano E; Liste I Role of Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) and Its Derivatives in the Biology and Cell Fate Specification of Neural Stem Cells. Mol Neurobiol 2018, 55 (9), 7107–7117. 10.1007/s12035-018-0914-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Mañucat-Tan NB; Saadipour K; Wang YJ; Bobrovskaya L; Zhou XF Cellular Trafficking of Amyloid Precursor Protein in Amyloidogenesis Physiological and Pathological Significance. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56 (2), 812–830. 10.1007/s12035-018-1106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Pike CJ; Overman MJ; Cotman CW Amino-Terminal Deletions Enhance Aggregation of β-Amyloid Peptides in Vitro. J Biol Chem 1995, 270 (41), 23895–23898. 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Schmechel A; Zentgraf H; Scheuermann S; Fritz G; Reed J; Beyreuther K; Bayer TA; Multhaup G Alzheimer β-Amyloid Homodimers Facilitate Aβ Fibrillization and the Generation of Conformational Antibodies*. J Biol Chem 2003, 278 (37), 35317–35324. 10.1074/jbc.M303547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Vandersteen A; Hubin E; Sarroukh R; De Baets G; Schymkowitz J; Rousseau F; Subramaniam V; Raussens V; Wenschuh H; Wildemann D; Broersen K A Comparative Analysis of the Aggregation Behavior of Amyloid-β Peptide Variants. FEBS Lett 2012, 586 (23), 4088–4093. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Dutta S; Foley AR; Warner CJA; Zhang X; Rolandi M; Abrams B; Raskatov JA Suppression of Oligomer Formation and Formation of Non-Toxic Fibrils upon Addition of Mirror-Image Aβ42 to the Natural l-Enantiomer. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2017, 56 (38), 11506–11510. 10.1002/anie.201706279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Petkova AT; Leapman RD; Guo Z; Yau W-M; Mattson MP; Tycko R Self-Propagating, Molecular-Level Polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid Fibrils. Science 2005, 307, 262–266. 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wolman M; Bubus JJ The Cause of the Green Polarization Color of Amyloid Stained with Congo Red. Histochemie 1965, 4 (5), 351–356. 10.1007/bf00306246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Espargaró A; Llabrés S; Saupe SJ; Curutchet C; Luque FJ; Sabaté R On the Binding of Congo Red to Amyloid Fibrils. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2020, 59, 1–5. 10.1002/anie.201916630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ali F; Thompson AJ; Barrow CJ The P3 Peptide, a Naturally Occurring Fragment of the Amyloid-β Peptide (Aβ) Found in Alzheimer’s Disease, Has a Greater Aggregation Propensity in Vitro than Full-Length Aβ, but Does Notbind Cu2+. Aust J Chem 2000, 53, 321–326. 10.1071/CH99169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Sawaya MR; Sambashivan S; Nelson R; Ivanova MI; Sievers SA; Apostol MI; Thompson MJ; Balbirnie M; Wiltzius JJW; Mcfarlane HT; Madsen AØ; Riekel C; Eisenberg D Atomic Structures of Amyloid Cross-β Spines Reveal Varied Steric Zippers. Nature 2007, 447, 453–457. 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kayed R; Head E; Sarsoza F; Saing T; Cotman CW; Necula M; Margol L; Wu J; Breydo L; Thompson JL; Rasool S; Gurlo T; Butler P; Glabe CG Fibril Specific, Conformation Dependent Antibodies Recognize a Generic Epitope Common to Amyloid Fibrils and Fibrillar Oligomers That Is Absent in Prefibrillar Oligomers. Mol Neurodegener 2007, 2 (1), 1–11. 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Westermark P; Benson MD; Buxbaum JN; Cohen AS; Ikeda S; Masters CL; Merlini G; Maria J; Sipe JD Amyloid: Toward Terminology Clarification Report from the Nomenclature Committee of the International Society of Amyloidosis. Amyloid 2005, 12, 1–4. 10.1080/13506120500032196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Benson MD; Buxbaum JN; Eisenberg DS; Merlini G; Saraiva MJM; Sekijima Y; Sipe JD; Westermark P Amyloid Nomenclature 2018: Recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) Nomenclature Committee. Amyloid 2018, 25 (4), 215–219. 10.1080/13506129.2018.1549825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lu J; Qiang W; Yau W; Schwieters CD; Meredith SC; Tycko R Molecular Structure of β-Amyloid Fibrils in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Tissue. Cell 2013, 154 (6), 1257–1268. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Garai K; Frieden C Quantitative Analysis of the Time Course of Aβ Oligomerization and Subsequent Growth Steps Using Tetramethylrhodamine-Labeled Aβ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013, 110 (9), 3321–3326. 10.1073/pnas.1222478110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Hardy J; Selkoe DJ The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and Problems on the Road to Therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353–356. 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Mclean CA; Cherny RA; Fraser FW; Fuller SJ; Smith MJ; Beyreuther K; Bush AI; Masters CL Soluble Pool of Aβ Amyloid as a Determinant of Severity of Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann Neurol 1999, 46 (6), 860–866. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Walsh DM; Klyubin I; Fadeeva JV; Cullen WK; Anwyl R; Wolfe MS; Rowan MJ; Selkoe DJ Naturally Secreted Oligomers of Amyloid-β Protein Potently Inhibit Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation in Vivo. Nature 2002, 416 (6880), 535–539. 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Li JJ; Dolios G; Wang R; Liao FF Soluble Beta-Amyloid Peptides, but Not Insoluble Fibrils, Have Specific Effect on Neuronal MicroRNA Expression. PLoS One 2014, 9 (3), e90770 10.1371/journal.pone.0090770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lesné S; Koh MT; Kotilinek L; Kayed R; Glabe CG; Yang A; Gallagher M; Ashe KH A Specific Amyloid-β Protein Assembly in the Brain Impairs Memory. Nature 2006, 440 (7082), 352–357. 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Brouillette J; Caillierez R; Zommer N; Alves-Pires C; Benilova I; Blum D; de Strooper B; Buée L Neurotoxicity and Memory Deficits Induced by Soluble Low-Molecular-Weight Amyloid-β 1–42 Oligomers Are Revealed in Vivo by Using a Novel Animal Model. J Neurosci 2012, 32 (23), 7852–7861. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5901-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ahmed M; Davis J; Aucoin D; Sato T; Ahuja S; Aimoto S; Elliott JI; Van Nostrand WE; Smith SO Structural Conversion of Neurotoxic Amyloid-Beta(1–42) Oligomers to Fibrils. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010, 17 (5), 561–567. 10.1038/nsmb.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Soreghan B; Kosmoski J; Glabe C Surfactant Properties of Alzheimer’s Aβ Peptides and the Mechanism of Amyloid Aggregation. J Biol Chem 1994, 269 (46), 28551–28554. https://doi.org/citeulike-article-id:3576076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dulin F; Léveillé F; Ortega JB; Mornon JP; Buisson A; Callebaut I; Colloc’h N P3 Peptide, a Truncated Form of Aβ Devoid of Synaptotoxic Effect, Does Not Assemble into Soluble Oligomers. FEBS Lett 2008, 582 (13), 1865–1870. 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Miller Y; Ma B; Nussinov R Polymorphism of Alzheimer’s Aβ17–42 (P3) Oligomers: The Importance of the Turn Location and Its Conformation. Biophys J 2009, 97 (4), 1168–1177. 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Liu R; McAllister C; Lyubchenko Y; Sierks MR Residues 17–20 and 30–35 of β-Amyloid Play Critical Roles in Aggregation. J Neurosci Res 2004, 75 (2), 162–171. 10.1002/jnr.10859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Fancy DA; Kodadek T Chemistry for the Analysis of Protein–Protein Interactions: Rapid and Efficient Cross-Linking Triggered by Long Wavelength Light. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1999, 96 (3), 6020–6024. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Bitan G; Vollers SS; Teplow DB Elucidation of Primary Structure Elements Controlling Early Amyloid Beta Protein Oligomerization. J Biol Chem 2003, 278 (37), 34882–34889. 10.1074/jbc.M300825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Bolognesi B; Kumita JR; Barros TP; Esbjorner EK; Luheshi LM; Crowther DC; Wilson MR; Dobson CM; Favrin G; Yerbury JJ ANS Binding Reveals Common Features of Cytotoxic Amyloid Species. ACS Chem Biol 2010, 5 (8), 735–740. 10.1021/cb1001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Spencer RK; Li H; Nowick JS X-Ray Crystallographic Structures of Trimers and Higher-Order Oligomeric Assemblies of a Peptide Derived from Aβ17–36. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136 (15), 5595–5598. 10.1021/ja5017409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Salveson PJ; Haerianardakani S; Thuy-Boun A; Kreutzer AG; Nowick JS Controlling the Oligomerization State of Aβ-Derived Peptides with Light. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140 (17), 5842–5852. 10.1021/jacs.8b02658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Streltsov VA; Varghese JN; Masters CL; Nuttall SD Crystal Structure of the Amyloid-β P3 Fragment Provides a Model for Oligomer Formation in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Neurosci 2011, 31 (4), 1419–1426. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4259-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Honda R Amyloid-β Peptide Induces Prion Protein Amyloid Formation: Evidence for Its Widespread Amyloidogenic Effect. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2018, 57 (21), 6086–6089. 10.1002/anie.201800197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Warner CJA; Dutta S; Foley AR; Raskatov JA Introduction of D-Glutamate at a Critical Residue of Aβ42 Stabilizes a Pre-Fibrillary Aggregate with Enhanced Toxicity. Chem - A Eur J 2016, 22 (34), 11967–11970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Nakka PP; Li K; Forciniti D Effect of Differences in the Primary Structure of the A-Chain on the Aggregation of Insulin Fragments. ACS OMEGA 2018, 3, 9636–9647. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Dutta S; Foley AR; Warner CJA; Zhang X; Rolandi M; Abrams B; Raskatov JA Suppression of Oligomer Formation and Formation of Non-Toxic Fibrils upon Addition of Mirror-Image Aβ42 to the Natural L-Enantiomer. Angew Chemie - Int Ed 2017, 56 (38), 11506–11510. 10.1002/anie.201706279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Dutta S; Finn TS; Kuhn AJ; Abrams B; Raskatov JA Chirality Dependence of Amyloid β Cellular Uptake and a New Mechanistic Perspective. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 1–5. 10.1002/cbic.201800708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.