Abstract

SARS-Cov2 coinfection with other respiratory viruses is very rare. Adenovirus coinfection is even more unusual. We report the case of a patient with poorly controlled diabetes, and he was admitted to the emergency department because of severe COVID-19 infection. He had unfavorable prognostic factors such as moderate oxygen impairment, positive D-dimer, increased lactate dehydrogenase and ferritin. Adenovirus was isolated in a respiratory viral panel. He developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required pronation and neuromuscular relaxation in the intensive care unit. Hydroxychloroquine was administered as suggested by the national guidelines. The symptoms resolved, and hospital discharge was indicated. COVID-19 association with another respiratory virus is related with adverse clinical outcomes, such as shock, ventilatory support requirement and greater lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia.

Keywords: Adenovirus infections, Pneumonia, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Coinfection, Case report

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (SARS CoV2) disease was first reported in the Wuhan province of Hubei, China in December 2019 [1,2]. This viral infection has affected a total of 6,931,000 population, including 400,857 deaths, across 5 continents and 187 countries (as of June 8, 2020) [3]

It has a diverse clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic infection or mild symptoms to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [4,5]. The most important prognostic factors are age (greater than 65 years), comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction [1,6,7] and altered tests such asdimer > 1 mcg / ml, LDH > 350 U / L, lymphocyte count less than 800, positive troponin and ferritin greater than 1000 [5,6].

Bacterial, fungal and viral coinfections with mycoplasma, legionella, influenza A/B, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza, associated with a worse patient prognosis [[8], [9], [10]], have also been reported. We report the unusual case of a patient with COVID-19 and adenovirus infection.

Case report

A 40-year-old man (a merchant by profession from Bogotá, Colombia) was admitted to the emergency department because of the history of odynophagia, dry cough, exertional dyspnea, fever of 39 degrees Celsius, arthralgias and fatigue for a week, without any gastrointestinal symptoms. These clinical symptoms did not improve with paracetamol, and hence he decided to seek further medical help. He had a history of poorly controlled diabetes (glycosylated hemoglobin 10.8 %), notwithstanding daily insulin treatment with 44 IU of glargine and 16 UI of lispro before each meal. No history of smoking or alcohol consumption was reported. On physical examination, he had a body mass index of 28.3 kg / m2 and vital signs were the following: heart rate 110 beats per minute, 24 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation of 82 % at ambiance. Right lung rales were also found without cyanosis or lower limb edema. The patient did not have a direct contact with a coronavirus case, but he had worked with public as part of his business.

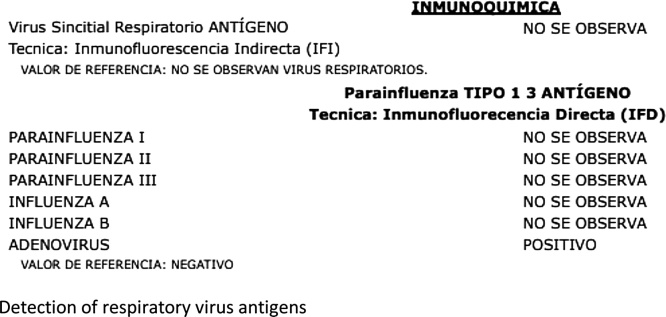

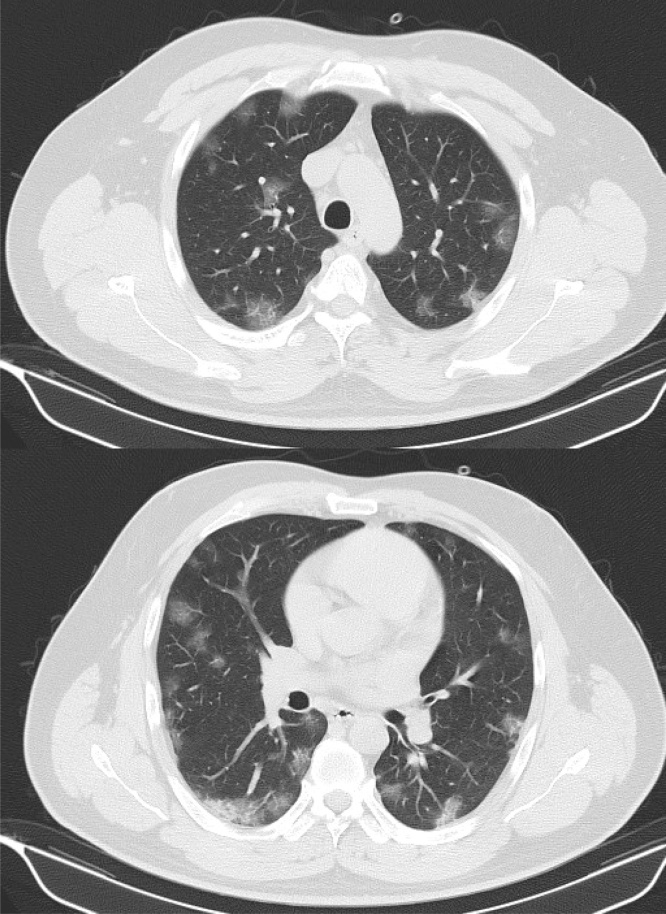

Arterial gases showed moderate oxygen impairment (PAFI 190), and supplemental oxygen was required. Further examination revealed a normal blood count but increased CRP. Right basal ground glass opacity was found during chest x-ray. Later, a positive RT-PCR COVID- 19 was reported, and adenovirus was isolated in the respiratory viral panel (Fig. 1). Owing to poor prognostic factors, the patient had increased lactate dehydrogenase, markedly elevated ferritin, positive D-dimer adjusted by age (Table 1) and ground-glass opacities with multilobar involvement on chest tomography, a classic COVID-19 pattern according to the American Society of Radiologists (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Detection of respiratory virus antigens.

Table 1.

Evolution of paraclinics.

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 12 | Day 15 | Day 18 | Day 23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC × 10⁹ per L | 4.6 | 6.1 | 8.9 | 11.7 | 15.3 | 10.6 | 6.64 |

| Lymphocyte absolute count × 10⁹ per L | 1.39 | 1.31 | 0.58 | 0.91 | 2.61 | 2.42 | 2.09 |

| Platelet count, × 10⁹ per L | 136 | 152 | 312 | 420 | 415 | 515 | 400 |

| C reactive proteine (mg/dl) | 14.18 | 25.68 | 20.93 | 14.79 | 3.25 | 9 | |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (UI/liter) | 229 | 419 | 455 | 437 | |||

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 0.65 | 0.97 | 3.66 | ||||

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 2296 | 4472 | 2913 | 2501 | |||

| ALT, U/L | 54 | 53 | 72 | 52 | 48 | 74 | |

| AST, U/L | 36 | 63 | 86 | 57 | 62 | 54 |

Fig. 2.

Chest tomography: multilobar, subpleural ground glass with areas of basal peripheral consolidation (classic COVID pattern).

On the sixth day after admission, he had increased dyspnea, tachypnea and desaturation despite supplemental oxygen, so he was transferred to the intensive care unit. Management with ampicillin-sulbactam and clarithromycin was empirically started, and hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily) was suggested according to national guidelines. Corrected Qt interval was monitored all the time. Hypotension and hypoxemia developed and did not improve despite using intravenous crystalloids and high flux oxygen, so mechanical ventilation and norepinephrine were started. Septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) were diagnosed. Pronation and neuromuscular relaxation cycles were also required, and Klebsiella oxytoca was isolated on blood cultures. Antibiotic escalation to cefepime was indicated, and a 10-day treatment was completed.

On day 18, successful extubation was achieved, and he was transferred to the general floor. The symptoms resolved, and the second RT-PCR SARS Cov2 report was negative. He was discharged on the twentieth day after admission, and the follow-up appointments revealed supplemental oxygen requirement at home.

Discussion

We report a case of SARS-Cov2 and adenovirus coinfection, which further developed into acute respiratory distress syndrome. ICU stay was required, and clinical improvement was achieved by using hydroxychloroquine as per the local guidelines, [11]. The exact time of coinfection could not be established, and additional poor prognostic factor to the development of severe disease added to patient´s comorbidities and reported tests [1,6].

SARS-Cov2 and other respiratory viruses´ coinfection are unusual. It is seen in 3.2 %–22.4 % cases [8,10]. The most common coinfections reported are enterovirus / rhinovirus 6.9 % and syncytial respiratory virus 5.2 %. [10,12]. A few case reports of influenza A, influenza B, metapneumovirus and seasonal coronaviruses such as Cov-HKU [9,10] can also be found in the literature, but coinfection with adenovirus has only been documented in 2 patients [13].

The pathophysiological dynamics of SARS-Cov2 coinfection is not clear. There are some hypotheses about the relatively low presentation of SARS-Cov2 virus, without a predisposing higher risk factor [8,14]. It was documented in descriptive studies that with coinfection, a greater proportion of the patients had ARDS and septic shock and required an ICU admission [10,14].

Chest tomography can show additional radiological findings, which are difficult to interpret [10]. Further laboratory findings revealed some differences such as greater lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia in coinfected patients. It is not known whether it is the cause or consequence of this coinfection [10,12,14].

Although coinfection is not common, in cases with severe disease or CT findings that are not explained by COVID-19 infection [11,14,15], additional studies such as nested PCR for respiratory germs are required to detect potentially treatable pathogens, such as mycoplasma or influenza virus [14].

Larger and better designed prospective analytical studies are required to determine further risk factors, clinical impact, prognosis, and the prevalence of SARS-Cov2 and another respiratory pathogen coinfection.

Conclusion

Although SARS-Cov2 coinfection with other respiratory viruses is rare, it is associated with a worse clinical outcome. The possibility of treatable pathogens must always be ruled out even if it is a very rare coinfection such as Covid-19 and adenovirus.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

All authors have made substantial contributions to the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- 1.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report– 140.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200608-covid-19-sitrep-140.pdf?sfvrsn=2f310900_2 n.d. (Accessed June 8, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koichi Y., Fujiogi M., Koutsogiannaki S. 2019. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X., Xu S., Yu M., Wang K., Tao Y., Zhou Y. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xing Q.-S., Li G.-J., Xing Y.-H., Chen T., Li W.-J., Ni W. 2020. Precautions are needed for COVID-19 patients with coinfection of common respiratory pathogens. n.d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azekawa S., Namkoong H., Mitamura K., Kawaoka Y., Saito F. Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus. IDCases. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z.-T., Chen Z.-M., Chen L.-D., Zhan Y.-Q., Li S.-Q., Cheng J. Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens in COVID-19 patients in Guangzhou, China. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saavedra Trujillo C.H. Consenso colombiano de atención, diagnóstico y manejo de la infección por SARS-COV-2/COVID 19 en establecimientos de atención de la salud. Recomendaciones basadas en consenso de expertos e informadas en la evidencia. Infectio. 2020;24:1. doi: 10.22354/in.v24i3.851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D., Quinn J., Pinsky B., Shah N.H., Brown I. Rates of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2085–2086. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowak M.D., Sordillo E.M., Gitman M.R., Paniz Mondolfi A.E. Co-infection in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients: where are influenza virus and rhinovirus/enterovirus? J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai C.-C., Wang C.-Y., Hsueh P.-R. Co-infections among patients with COVID-19: the need for combination therapy with non-anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents? J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blasco M.L., Buesa J., Colomina J., Forner M.J., Galindo M.J., Navarro J. Co‐detection of respiratory pathogens in patients hospitalized with coronavirus viral disease‐2019 pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25922. jmv.25922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]