Abstract

Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange (SABRE) is a particularly simple hyperpolarisation approach. However, compared to other hyperpolarisation methods, SABRE is more limited in substrate scope. Therefore, it is critical to understand and overcome the factors limiting generalization. Past developments in SABRE catalyst optimization have emphasized large enhancements in the canonical SABRE substrate: pyridine and structurally closely related motifs. However, the pyridine-optimized catalysts are not efficient at hyperpolarising more sterically demanding substrates, including 2-substituted pyridine derivatives. Here we report that modifications of the catalyst ligand sphere, using a chelating ligand in particular, can increase the volume fraction available for substrate coordination to the iridium catalyst, thus permitting significant signal enhancements on otherwise sterically hindered substrates. The system yields 1H enhancements on the order of 100-fold over 8.5 T thermal measurements for 2-substituted pyridine derivatives, and smaller, yet significant 1H enhancement for provitamin B6 and caffeine. For the 2-substituted pyridine derivatives we further show 15N enhancements on the order of 1000-fold and 19F enhancements of 30-fold over 8.5 T thermal polarisations.

Graphical Abstract

Phox ligands enable new substrates for SABRE.

Introduction

Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange (SABRE) is a relatively recent discovery among hyperpolarisation methods (2009).1-5 Hyperpolarisation is transferred from para-hydrogen (p-H2) to nuclei in a substrate molecule through J-coupling interactions mediated by the metal centre of a polarisation transfer catalyst. Both parahydrogen and substrate are in reversible exchange on the catalyst and polarisation flows from parahydrogen derived hydrides6 to ligated substrates during the lifetime of the complex. 1, 7

SABRE is an attractive hyperpolarisation technique because it allows for efficient polarisation of 1H and 15N spins within about one minute.8-10 The technique uses simple and low-cost hardware and has been expanded to a wide range of other spin-1/2 nuclei including 13C, 19F, 31P, and others5, 11-16 Moreover, heterogeneous SABRE and SABRE in aqueous medium have been demonstrated.17-27 All-in-all, this technique has made large advances for preparation of hyperpolarised substances, and has demonstrated the potential to generate injectable hyperpolarised contrast agents for in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging.28-32,33

In this paper, we capitalize on the simple insight that steric considerations are of essence and can make a drastic difference in SABRE efficiency. Particularly, substrate size and binding pocket must be well matched. Guided by this insight, we introduce a hyperpolarisation catalyst able to hyperpolarise larger, sterically hindered substrates, primarily 2-substituted pyridines, that are not efficiently hyperpolarised with current widely used catalysts.10, 34 Moreover, we demonstrate hyperpolarisation of provitamin B6 and caffeine, which bear substituents in the ortho position to the N-heteroatom as well.

Historically, SABRE was discovered with Crabtree’s catalyst [Ir(PR3)(pyr)(COD)]PF6 (1) (R = cyclohexyl, pyr = pyridine, COD = 1,5-cyclooctadiene) (see Figure 1)1. Initially, 1H signal amplifications over thermal signals (enhancements) were found to scale favourably with electron density and steric bulk of the phosphine ligand2, but phosphine ligands were quickly replaced by N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs), most importantly, IMes35 (2) and (2a) (Figs. 1 and 2, IMes = 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazole-2-ylidene)), giving rise to a drastic increase of enhancements.35-37

Figure 1:

Three generations of catalysts for SABRE. The canonical Crabtree’s catalyst (1), the IMes catalyst (2) yielding maximal enhancements on pyridine, and the Phox catalyst (3) applicable to sterically demanding substrates, as shown here. Coligands (CoL) are constituted by solvent, substrate or an auxiliary compound.

Figure 2:

A) Comparison of the structure of [Ir(H)2(IMes)(pyr)3]+ (2a) and the structure predicted for [Ir(H)2(Phox)(MP)2]+ (3a) (MP = 2-methylpyridine). B) Experimental Spectrum (red) and fit (dashed line, cyan) of the hydride resonances of (3a). For the experiment, constant para-H2 flow was supplied at 8.45 T and the excitation pulse is 45°. The fit is the sum of individual resonances (blue curves). The maxima of the blue curves can be used to extract δ = −19.03 and −22.55 ppm, using JHH’ ≈ −7 Hz, JHP = JH’P ≈ 20 Hz as shown in the small insets directly above the spectra. With a chemical shift difference of approximately 3.5 ppm, a PASADENA-like spectrum is obtained.

Most optimization efforts using the NHC motif were geared towards pyridine and structurally similar compounds.38, 39 Large improvements for 1H SABRE were recently afforded with perdeuterated8 or chlorinated 40 variant of the [IrCl(IMes)(COD)] (2) system with record polarisations on the order of 50%. However, these improvements do not extend to other substrates with higher steric demands. In efforts to target a broader substrate scope, auxiliary compounds (co-ligands) have been utilized to increase the number of viable polarisation transfer targets and to focus transferred polarisation.16, 41-44 Also, chelating ligands have been explored, but polarisation levels remained low. 45, 46 While a variety of smaller pyrazole derivatives were studied in Ref.47, polarisation on 2-substituted pyridines was not reported.

Here we demonstrate that [Ir(COD)(Phox)]PF6 (3) (Phox = 2-(2-(diphenylphosphanyl)phenyl)-4,5-dihydrooxazole) (Figure 1), a catalyst for asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins48, can serve as a polarisation transfer catalyst for more sterically demanding substrates.49, 50 We target 1H, 15N and 19F hyperpolarisation in ortho-substituted pyridine derivatives, including provitamin B6 and caffeine. It is noteworthy, that although (3) performs worse as a polarisation transfer catalyst for pyridine, compared to (2), it is superior for sterically congested substrates, which are not hyperpolarised with the IMes catalyst (2) at all.

As illustrated in Figure 1, in SABRE experiments, precatalysts are transformed into their catalytically active species under a H2 atmosphere in presence of polarisation transfer targets. For precatalyst (2) and the substrate pyridine, one obtains [Ir(H)2(IMes)(pyr)3]+ (2a). This dihydride derived from p-H2 constitutes the catalytically active complex in polarisation transfer reactions.35, 51 One important consequence of monodentate ligands (e.g. an NHC or Phosphines) and the octahedral iridium dihydride complexes is that three sites remain for coordination (pyridine in (2a)). By using a bidentate ligand, such as [Ir(COD)(Phox)]PF6 (3) the binding pocket size is significantly increased over that of complexes with monodentate ligands.

When pre-catalyst (3) is activated under a hydrogen atmosphere in the presence of substrates, (3a) is formed (see Fig. 1 and 2A). Evidence for (3a) is provided by NMR data (Fig. 2B and see below) and accompanying density-functional theory (DFT) calculations.52-56 The DFT code used (FHI-aims52, 57, 58) is a high-precision, all-electron implementation that has been benchmarked extensively in past work,59, 60 including a history of successful use for molecular structure prediction (e.g., Refs.61-64). Detailed analysis of the DFT calculations, including extensive benchmark and validation data for the methods used, is presented in the Supporting Information. The DFT calculations find (3a) to be the lowest energy dihydride complex. Consistent with this structure, we find different chemical shifts for the two hydride species attached to Ir, as displayed in Fig. 2. Specifically, if para-hydrogen is bubbled through the solution at high field (8.45 T) the anti-phase spectrum of Figure 2B is obtained. 65, 66 We observe chemical shifts of −19.0 and −22.5 ppm for the hydride resonances, pointing to trans-to nitrogen coordination for both hydrides, where the chemical shift at −22.5 ppm is identical with the trans-to-pyridine hydride in (2a).

The observed hydride to hydride J-coupling in (3a) is JHH’ ≈ −7 Hz and the hydride to 31P J-couplings are JHP = JH’P ≈ 20 Hz. The J-couplings, chemical shifts, and magnetic field dependence of hyperpolarisation (see supplement) are very similar to those of Crabtree’s catalyst, serving as further evidence for structure (3a). While a full conformational study of (3a) at relatively low concentrations remains beyond the scope of this work, the proposed structure (3a) provides a consistent mechanistic explanation for the main observation of this paper, which is the ability of (3) and its activated state to successfully hyperpolarize substrates that are much more difficult to access with other commonly used catalysts.

We found that (3) allows 1H polarisation in a range of 2-substituted pyridines, where the conventional IMes catalyst (2) is not applicable. Table 1 contrasts 1H enhancements obtained with the first-generation Crabtree’s catalyst (1), the IMes catalyst (2) optimized for pyridine, and the bidentate Phox catalyst (3). As in studies using (1), maximum enhancements on substrate 1H nuclei with (3) are obtained at 140 G irrespective of substrate identity (see SI). This is consistent with the study of Pravdivtsev et al., where presence of 31P in the first coordination sphere of Ir changes the matching conditions to a higher magnetic field when compared to (2).67 It is noteworthy that catalyst (3) yields enhancements of aromatic protons in α-picoline and 2-fluoropyridine (Table 1, entries 2 and 3), comparable to those originally reported for SABRE with Crabtree’s catalyst (1) and pyridine (Table 1, entry 1).1, 2 Interestingly, Crabtree’s catalyst yields a small but non-negligible hyperpolarisation effect on 2-fluoropyridine in that the sign of the polarisation changed compared to simple thermal polarisation. This shows that the activity of Crabtree’s catalysts is not strictly zero for this substrate but still drastically lower than that of the Phox catalyst (3). Similar small but non-zero activity is possible for the other cases labeled “-” in Table 1, however, remained below the detection limits of our experiments.

Table 1:

Comparison of average 1H enhancements ε at RT (over thermal signals at 8.5 T). Asterisks in the molecular sketches denote the enhanced 1H moieties. No enhancements are observed for substrate 6.

The enhancements for aliphatic proton are relatively poor for all entries (~10-fold). Comparing entries 2 and 4, increasing the chain length of the aliphatic substituent reduces aromatic proton enhancements by 80%. Potentially the most interesting structure, from an application viewpoint, is provitamin B6 (entry 5). In our experiments, enhancements of aromatic and aliphatic protons of 7 and 2 respectively were achieved. The enhancements were limited since the provitamin B6 was commercially available only as a hydrochloride salt, which necessitated addition of a base (triethylamine or NaOD) for neutralization. This procedure also resulted in addition of a small amount of water, which reduces SABRE efficiency somewhat. Regarding the limitations by sterical congestion, we note that hyperpolarisation of 2,6-dimethylpyridine (entry 6) remained unsuccessful. To rationalize this finding, we show in the supplement (Figure S5, Table S9, as well as an analysis of strain effects in Supplemental section 2d and Tables S10-S13) that DFT modelling of the substitution of 2-methylpyridine (entry 2) in (3a) by 2,6-dimethylpyridine results in an approximate energy increase of +0.5 eV (48 kJ/mol), much larger than NakBT. Adding additional co-ligands (CH3CN, H2O, Pyridine), an approach that was successful in prior instances with sterically hindered substrates,10, 16, 41, 43, 68 also failed to effect hyperpolarisation of 2,6-dimethylpyridine in the present work. Entries 1 (pyridine) and 7 (caffeine) show small but non-zero enhancements. For caffeine (entry 7), small enhancements are expected as caffeine is the largest substrate we examined and may require a catalyst optimized for even larger motifs.

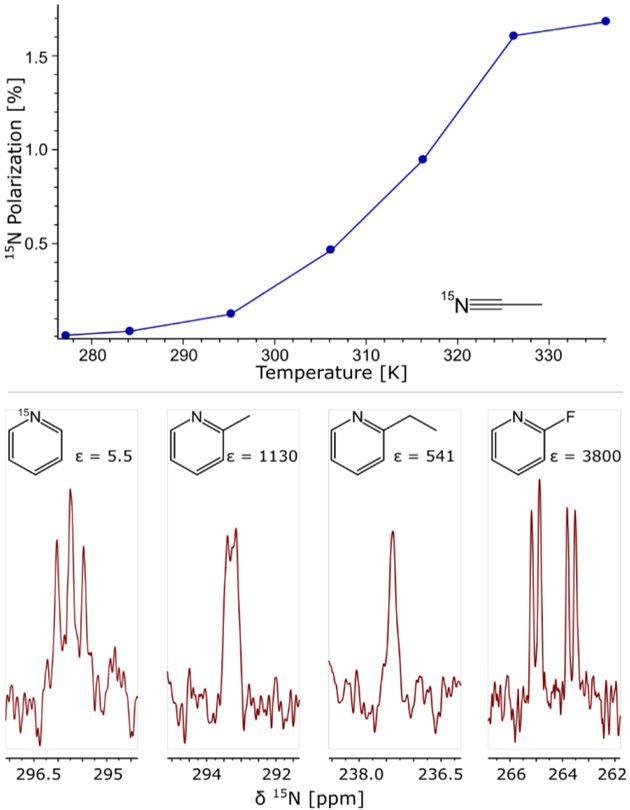

Next, we used the Phox catalyst (3) for polarising 15N at μT magnetic fields with SABRE-SHEATH. 7, 10, 17, 69-71 The simple substrate CH3CN has previously been found to show 190-fold 1H polarisation enhancements when used as a coligand with the IMes catalyst.72 We investigated 15N polarisation with CH3C15N (50 mM) and 2.6 mM solutions of (3) as a function of temperature at microTesla fields as displayed in Fig. 3. We found that 15N polarisation levels of 1.5 % are readily obtained, identical to polarisation levels achieved with (2) at these moderately high concentrations.10 As indicated in Fig. 3, the optimal temperature is elevated when using the Phox catalyst (3). Here the maximum is found between 60 °C and 70 °C, whereas IMes works best at room temperature for 15N-acetonitrile (2).10 Next, as shown in the bottom of Fig. 3, the Phox catalyst (3) hyperpolarises 15N at natural abundance in substrates 1–4 using 2.6 mM catalyst and 50 mM substrate (see Fig. 3, bottom). Notice that the nitrogen enhancements ε are larger for 15N than for 1H. However, the absolute polarisation levels are similar because the enhancement refers to thermal polarisation of 15N, which is ten times lower than for 1H. We also note that similar temperature dependent measurements were not possible for 1H with our present setup since 1H relaxation times are shorter, leading to larger uncertainties as a result of having to transfer samples manually between a temperature controlled mT field environment and the spectrometer.

Figure 3:

(Top) 15N Polarisation with PHOX (3) as a function of the sample temperature during polarisation build-up on 15N labelled CH3CN in the magnetic shield. Evolution field is 0.66 μT, build-up time 60 s. (Bottom) 15N spectra of naturally abundant 2-substituted pyridine derivatives and 15N labelled pyridine hyperpolarised by SABRE-SHEATH at room temperature. 2.6 mM catalyst (3) and 50 mM substrate were used in all samples.

Finally, we also tested the previously challenging12 19F polarisation of 2-fluoropyridine (i.e., 19F in the ortho position) and achieved a 30-fold enhancement over thermal polarisation at 9.4 T, at an optimised polarisation transfer field of 5.4 mT (Figure S15 in the supplement). In Ref.12, it was shown that 19F in the ortho position was difficult to hyperpolarize with the IMes catalyst (attributed to steric hindrance) whereas here we achieve hyperpolarisation with the Phox catalyst.

In conclusion, the introduced PHOX multidentate ligand for SABRE catalysts allows for polarisation of bulkier substrates, including biologically relevant molecules such as provitamin B6 or caffeine. Interestingly, hyperpolarisation is worse for pyridine than for 2-substituted pyridine derivatives. This shows that testing potential SABRE catalysts on a small set of substrates is insufficient and opportunities for expanding the SABRE substrate scope may be missed. Indeed, the Phox catalyst performs better than the highly optimised (for pyridine) IMes catalyst when considering bulkier substrates. Moreover, attractive features of chelating ligands, such as reliable immobilization and simplification of kinetics to supress non-hyperpolarising exchange pathways, give a promising handle towards the rational design of SABRE catalysts. Altogether, these finding provide a path towards a broader scope of SABRE hyperpolarisation with numerous applications in biomedicine and beyond.42, 73

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

There are no conflicts of interests to declare. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the NIH (R21EB025313). We also gratefully acknowledge funding by the NSF (CHE-1665090) and by Duke University. EYC is grateful for funding support from NSF CHE-1904780, NIH 1R21EB020323 and 1R21CA220137; and DOD CDMRP W81XWH-12–1-0159/BC112431 and W81XWH-15–1-0271. Furthermore, support from the Donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Synthesis of the catalyst, detailed DFT calculations, spectral data, magnetic evolution field dependence, and description of experimental details. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Adams RW, Aguilar JA, Atkinson KD, Cowley MJ, Elliott PIP, Duckett SB, Green GGR, Khazal IG, Lopez-Serrano J and Williamson DC, Science, 2009, 323, 1708–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson KD, Cowley MJ, Elliott PIP, Duckett SB, Green GGR, López-Serrano J and Whitwood AC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2009, 131, 13362–13368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams RW, Duckett SB, Green RA, Williamson DC and Green GGR, J. Chem. Phys, 2009, 131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikolaou P, Goodson BM and Chekmenev EY, Chem. Eur. J, 2015, 21, 3156–3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hövener J-B, Pravdivtsev AN, Kidd B, Bowers CR, Glöggler S, Kovtunov KV, Plaumann M, Katz-Brull R, Buckenmaier K, Jerschow A, Reineri F, Theis T, Shchepin RV, Wagner S, Zacharias NMM, Bhattacharya P and Chekmenev EY, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed , 2018, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201711842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duckett SB and Wood NJ, Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 2008, 252, 2278–2291. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theis T, Truong ML, Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Waddell KW, Shi F, Goodson BM, Warren WS and Chekmenev EY, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 1404–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rayner PJ, Burns MJ, Olaru AM, Norcott P, Fekete M, Green GGR, Highton LAR, Mewis RE and Duckett SB, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 2017, 114, E3188–E3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barskiy DA, Shchepin RV, Coffey AM, Theis T, Warren WS, Goodson BM and Chekmenev EY, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 8080–8083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colell JFP, Logan AWJ, Zhou Z, Shchepin RV, Barskiy DA, Ortiz GX, Wang Q, Malcolmson SJ, Chekmenev EY, Warren WS and Theis T, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2017, 6626–6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Z, Yu J, Colell JFP, Laasner R, Logan A, Barskiy DA, Shchepin RV, Chekmenev EY, Blum V, Warren WS and Theis T, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2017, 8, 3008–3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olaru AM, Robertson TBR, Lewis JS, Antony A, Iali W, Mewis RE and Duckett SB, ChemistryOpen, 2018, 7, 97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shchepin RV, Goodson BM, Theis T, Warren WS and Chekmenev EY, Chem. Phys. Chem, 2017, 18, 1961–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barskiy DA, Shchepin RV, Tanner CPN, Colell JFP, Goodson BM, Theis T, Warren WS and Chekmenev EY, Chem. Phys. Chem, 2017, 18, 1493–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhivonitko VV, Skovpin IV and Koptyug IV, Chem. Commun, 2015, 51, 2506–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mewis RE, Green RA, Cockett MCR, Cowley MJ, Duckett SB, Green GGR, John RO, Rayner PJ and Williamson DC, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2015, 119, 1416–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colell JFP, Emondts M, Logan AWJ, Shen K, Bae J, Shchepin RV, Ortiz GX, Spannring P, Wang Q, Malcolmson SJ, Chekmenev EY, Feiters MC, Rutjes FPJT, Blümich B, Theis T and Warren WS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2017, 139, 7761–7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmkuhl S, Emondts M, Schubert L, Spannring P, Klankermayer J, Blümich B and Schleker P, Chem. Phys. Chem, 2017, DOI: 10.1002/cphc.201700750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spannring P, Reile I, Emondts M, Schleker PPM, Hermkens NKJ, van der Zwaluw NGJ, van Weerdenburg BJA, Tinnemans P, Tessari M, Blümich B, Rutjes FPJT and Feiters MC, Chem. Eur. J, 2016, 22, 9277–9282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovtunov KV, Kovtunova LM, Gemeinhardt ME, Bukhtiyarov AV, Gesiorski J, Bukhtiyarov VI, Chekmenev EY, Koptyug IV and Goodson BM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 10433–10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi F, He P, Best QA, Groome K, Truong ML, Coffey AM, Zimay G, Shchepin RV, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY and Goodson BM, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2016, 120, 12149–12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truong ML, Shi F, He P, Yuan B, Plunkett KN, Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Barskiy DA, Kovtunov KV, Koptyug IV, Waddell KW, Goodson BM and Chekmenev EY, J. Phys. Chem. B, 2014, 18 13882–13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng H, Xu J, McMahon MT, Lohman JAB and van Zijl PCM, J. Magn. Reson, 2014, 246, 119–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fekete M, Gibard C, Dear GJ, Green GGR, Hooper AJJ, Roberts AD, Cisnetti F and Duckett SB, Dalton Trans., 2015, 44, 7870–7880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hövener J-B, Schwaderlapp N, Borowiak R, Lickert T, Duckett SB, Mewis RE, Adams RW, Burns MJ, Highton LAR, Green GGR, Olaru A, Hennig J and von Elverfeldt D, Anal. Chem, 2014, 86, 1767–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi F, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY and Goodson BM, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 7525–7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi F, Coffey AM, Waddell KW, Chekmenev EY and Goodson BM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2014, 53, 7495–7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olaru AM, Burns MJ, Green GGR and Duckett SB, Chem. Sci, 2017, 8, 2257–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shchepin RV, Barskiy DA, Coffey AM, Theis T, Shi F, Warren WS, Goodson BM and Chekmenev EY, ACS Sensors, 2016, 640–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng H, Xu J, Gillen J, McMahon MT, Artemov D, Tyburn J-M, Lohman JAB, Mewis RE, Atkinson KD, Green GGR, Duckett SB and van Zijl PCM, J. Magn. Reson, 2013, 237, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy SS, Appleby KM, Fear EJ and Duckett SB, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2018, 9, 1112–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayner PJ and Duckett S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2018, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201710406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Appleby KM, Mewis RE, Olaru AM, Green GGR, Fairlamb IJS and Duckett SB, Chem. Sci, 2015, 6, 3981–3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shchepin RV, Truong ML, Theis T, Coffey AM, Shi F, Waddell KW, Warren WS, Goodson BM and Chekmenev EY, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2015, 6, 1961–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowley MJ, Adams RW, Atkinson KD, Cockett MCR, Duckett SB, Green GGR, Lohman JAB, Kerssebaum R, Kilgour D and Mewis RE, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2011, 133, 6134–6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bantreil X and Nolan SP, Nat. Protoc, 2010, 6, 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lloyd LS, Asghar A, Burns MJ, Charlton A, Coombes S, Cowley MJ, Dear GJ, Duckett SB, Genov GR, Green GGR, Highton LAR, Hooper AJJ, Khan M, Khazal IG, Lewis RJ, Mewis RE, Roberts AD and Ruddlesden AJ, Catal. Sci. Technol, 2014, 4, 3544–3554. [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Weerdenburg BJA, Eshuis N, Tessari M, Rutjes FPJT and Feiters MC, Dalton Trans., 2015, 15387–15390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Weerdenburg BJA, Glöggler S, Eshuis N, Engwerda AHJ, Smits JMM, de Gelder R, Appelt S, Wymenga SS, Tessari M, Feiters MC, Blümich B and Rutjes FPJT, Chem. Commun, 2013, 49, 7388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rayner PJ, Norcott P, Appleby KM, Iali W, John RO, Hart SJ, Whitwood AC and Duckett SB, Nat. Commun, 2018, 9, 4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eshuis N, Aspers RLEG, van Weerdenburg BJA, Feiters MC, Rutjes FPJT, Wijmenga SS and Tessari M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 14527–14530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eshuis N, van Weerdenburg BJA, Feiters MC, Rutjes FPJT, Wijmenga SS and Tessari M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 1372–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reile I, Aspers RLEG, Tyburn J-M, Kempf JG, Feiters MC, Rutjes FPJT and Tessari M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 9174–9177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eshuis N, Hermkens N, van Weerdenburg BJA, Feiters MC, Rutjes FPJT, Wijmenga SS and Tessari M, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2014, 136, 2695–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmes AJ, Rayner PJ, Cowley MJ, Green GGR, Whitwood AC and Duckett SB, Dalton Trans., 2015, 44, 1077–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruddlesden AJ, Mewis RE, Green GGR, Whitwood AC and Duckett SB, Organometallics, 2015, 34, 2997–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ducker EB, Kuhn LT, Munnemann K and Griesinger C, Journal of magnetic resonance, 2012, 214, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazet C, Smidt SP, Meuwly M and Pfaltz A, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 14176–14181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfaltz A, Blankenstein J, Hilgraf R, Hörmann E, McIntyre S, Menges F, Schönleber M, Smidt SP, Wüstenberg B and Zimmermann N, Adv. Synth. Catal, 2003, 345, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wüstenberg B and Pfaltz A, Adv. Synth. Catal, 2008, 350, 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barskiy DA, Pravdivtsev AN, Ivanov KL, Kovtunov KV and Koptyug IV, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 2015, 89, 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blum V, Gehrke R, Hanke F, Havu P, Havu V, Ren X, Reuter K and Scheffler M, Comput. Phys. Commun, 2009, 180, 2175–2196. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sinstein M, Scheurer C, Matera S, Blum V, Reuter K and Oberhofer H, J. Chem. Theory Comput, 2017, 13, 5582–5603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perdew JP, Burke K and Ernzerhof M, Phys. Rev. Lett, 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tkatchenko A and Scheffler M, Phys. Rev. Lett, 2009, 102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao Y and Truhlar DG, Theor. Chem. Acc, 2007, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havu V, Blum V, Havu P and Scheffler M, Journal of Computational Physics, 2009, 228, 8367–8379. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ren X, Rinke P, Blum V, Wieferink J, Tkatchenko A, Sanfilippo A, Reuter K and Scheffler M, New Journal of Physics, 2012, 14. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lejaeghere K, Bihlmayer G, Björkman T, Blaha P, Blügel S, Blum V, Caliste D, Castelli IE, Clark SJ, Dal Corso A, de Gironcoli S, Deutsch T, Dewhurst JK, Di Marco I, Draxl C, Dułak M, Eriksson O, Flores-Livas JA, Garrity KF, Genovese L, Giannozzi P, Giantomassi M, Goedecker S, Gonze X, Grånäs O, Gross EKU, Gulans A, Gygi F, Hamann DR, Hasnip PJ, Holzwarth NAW, Iuşan D, Jochym DB, Jollet F, Jones D, Kresse G, Koepernik K, Küçükbenli E, Kvashnin YO, Locht ILM, Lubeck S, Marsman M, Marzari N, Nitzsche U, Nordström L, Ozaki T, Paulatto L, Pickard CJ, Poelmans W, Probert MIJ, Refson K, Richter M, Rignanese G-M, Saha S, Scheffler M, Schlipf M, Schwarz K, Sharma S, Tavazza F, Thunström P, Tkatchenko A, Torrent M, Vanderbilt D, van Setten MJ, Van Speybroeck V, Wills JM, Yates JR, Zhang G-X and Cottenier S, Science, 2016, 351.27463660 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jensen SR, Saha S, Flores-Livas JA, Huhn W, Blum V, Goedecker S and Frediani L, The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 2017, 8, 1449–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rossi M, Blum V, Kupser P, Von Helden G, Bierau F, Pagel K, Meijer G and Scheffler M, Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 2010, 1, 3465–3470. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chutia S, Rossi M and Blum V, Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2012, 116, 14788–14804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rossi M, Chutia S, Scheffler M and Blum V, The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 2014, 118, 7349–7359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schubert F, Rossi M, Baldauf C, Pagel K, Warnke S, von Helden G, Filsinger F, Kupser P, Meijer G, Salwiczek M, Koksch B, Scheffler M and Blum V, Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP, 2015, 17, 7373–7385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Theis T, Ortiz GX, Logan AWJ, Claytor KE, Feng Y, Huhn WP, Blum V, Malcolmson SJ, Chekmenev EY, Wang Q and Warren WS, Sci. Adv, 2016, 2, e1501438–e1501438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bowers CR and Weitekamp DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1987, 109, 5541–5542. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pravdivtsev AN, Yurkovskaya AV, Vieth H-M, Ivanov KL and Kaptein R, Chem. Phys. Chem, 2013, 14, 3327–3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shen K, Logan AWJ, Colell JFP, Bae J, Ortiz GX, Theis T, Warren WS, Malcolmson SJ and Wang Q, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2017, 56, 12112–12116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Truong ML, Theis T, Coffey AM, Shchepin RV, Waddell KW, Shi F, Goodson BM, Warren WS and Chekmenev EY, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 8786–8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roy SS, Stevanato G, Rayner PJ and Duckett SB, J. Magn. Reson, 2017, 285, 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Theis T, Truong M, Coffey AM, Chekmenev EY and Warren WS, J. Magn. Reson, 2014, 248, 23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fekete M, Rayner PJ, Green GGR and Duckett SB, Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 2017, 55, 944–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shchepin RV, Barskiy DA, Coffey AM, Goodson BM and Chekmenev EY, ChemistrySelect, 2016, 1, 2552–2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.