Abstract

Background

Adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) is a commonly used viral vector for transient delivery of transgenes, primarily for vaccination against pathogen and tumor antigens. However, endemic infections with Ad5 produce virus-specific neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) that limit transgene delivery and constrain target-directed immunity following exposure to Ad5-based vaccines. Indeed, clinical trials have revealed the limitations that virus-specific NAbs impose on the efficacy of Ad5-based vaccines. In that context, the emerging focus on immunological approaches targeting cancer self-antigens or neoepitopes underscores the unmet therapeutic need for more efficacious vaccine vectors.

Methods

Here, we evaluated the ability of a chimeric adenoviral vector (Ad5.F35) derived from the capsid of Ad5 and fiber of the rare adenovirus serotype 35 (Ad35) to induce immune responses to the tumor-associated antigen guanylyl cyclase C (GUCY2C).

Results

In the absence of pre-existing immunity to Ad5, GUCY2C-specific T-cell responses and antitumor efficacy induced by Ad5.F35 were comparable to Ad5 in a mouse model of metastatic colorectal cancer. Furthermore, like Ad5, Ad5.F35 vector expressing GUCY2C was safe and produced no toxicity in tissues with, or without, GUCY2C expression. Importantly, this chimeric vector resisted neutralization in Ad5-immunized mice and by sera collected from patients with colorectal cancer naturally exposed to Ad5.

Conclusions

These data suggest that Ad5.F35-based vaccines targeting GUCY2C, or other tumor or pathogen antigens, may produce clinically relevant immune responses in more (≥90%) patients compared with Ad5-based vaccines (~50%).

Keywords: gastrointestinal neoplasms, immunization, immunogenicity, vaccine, immunotherapy, active, vaccination

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies have revolutionized cancer treatment and cancer drug development by engaging the immune system to target various cancers.1 2 Despite this success, many tumors are immunologically “cold,” characterized by a dearth of immunogenic neoepitopes3 and lack of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes,4 5 and remain refractory to checkpoint inhibitors.6 7 One emerging strategy to modify a cold tumor into one responsive to immunotherapy is through combination with cancer vaccines.8 9 The goal of this strategy is to use cancer vaccines to create a pool of tumor-reactive T cells with antitumor activity alone and/or in combination with checkpoint therapies. However, this approach is significantly limited by the paucity of effective vaccine platforms to safely deliver tumor-specific/associated antigens to elicit beneficial antitumor immunity.

The ability of adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) to mediate gene transfer and induce potent immune responses has made it a popular vector for experimental vaccines against cancer and infectious diseases.10 Indeed, there have been more than 400 clinical trials using the Ad5 vector, with most trials focused on developing cancer treatments.10 11 However, on natural infection, the host immune system develops neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) to the Ad5 capsid, limiting viral spread and blocking reinfection. Because Ad5 infections are endemic in many human populations, pre-existing NAbs present in >70% of the worldwide population limit Ad5-based vaccine strategies.12–14 These considerations highlight the need for improved vectors for use in vaccines targeting cancer and pathogen-associated antigens that can create therapeutic immune responses in the greatest number of patients. Importantly, while the adenovirus capsid is composed of hexon, penton, and fiber proteins, NAbs elicited by natural Ad5 infection in humans are directed primarily to the Ad5 fiber,15 16 suggesting that strategies to circumvent pre-existing immunity to this element may improve Ad5-based vaccines.

Here, we sought to overcome pre-existing Ad5 NAbs by replacing the Ad5 fiber with that of a rare adenovirus serotype, Ad35 (international seroprevalence ~10%12–14), to improve antitumor immunity in mouse models expressing the gastrointestinal (GI) cancer antigen guanylyl cyclase C (GUCY2C). Preclinical models demonstrated that an Ad5-based GUCY2C-directed vaccine (Ad5-GUCY2C-S1) elicited CD8+ T-cell and antibody responses without autoimmunity.17 18 Further, Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 vaccination of mice induced long-term T-cell-mediated protection against metastatic colorectal cancer in lung and liver.19 20 Moreover, those results were recapitulated in a recent first-in-human phase I clinical trial (NCT01972737) demonstrating that a humanized version of the vaccine (Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE) safely induced GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in patients with colorectal cancer following conventional therapies.21 However, patients possessing high pre-existing titers of NAbs against Ad5 failed to generate GUCY2C-specific immunity following Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE vaccination.21 To overcome Ad5 NAbs, we generated a chimeric Ad5 vector possessing the fiber of Ad35 (Ad5.F35) with equivalent safety and antitumor activity to Ad5 and resistance to Ad5 NAbs in mice and humans. This chimeric vaccine can be translated to patients with GI cancer to safely induce GUCY2C-specific immunity not only in those patients with low Ad5 immunity but also in those with high pre-existing Ad5 NAbs.

Materials and methods

Adenovirus vectors

Adenovirus containing mouse extracellular domain (GUCY2C1-429) with the influenza HA107-119 CD4+ T-cell epitope known as site 1 (S1) was described previously (Ad5-GUCY2C-S1).20 Here, GUCY2C-S1 was cloned into pShuttle and subcloned into the E1 region of previously generated replication-deficient chimeric adenovirus (Ad5.F35) in which the Ad5 fiber was replaced by the Ad35 fiber22 to generate Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1. All adenovirus vaccines used in this study were produced in HEK293 cells and purified by cesium chloride ultracentrifugation under Good Laboratory Practices by the Baylor College of Medicine in the Cell and Gene Therapy Vector Development Lab and certified to be negative for replication-competent adenovirus, mycoplasma, and host cell DNA contamination. In vitro GUCY2C-expression experiments (dose–response and time–course) were carried out in A549 (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)) cells. Virus was added to the cultures at the indicated doses and culture supernatants were collected at the indicated time points. Relative GUCY2C levels were quantified in supernatants by western blot using 2 μg/mL MS7 mouse anti-GUCY2C monoclonal antibody23–25 and 0.1 μg/mL horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno).

Mice and immunizations

Eight-week old male and female BALB/cJ mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory for experiments. Animal protocols were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol 02092). For immunizations, mice received 1010 or 1011 vp of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1, Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1, or Ad5.F35-GFP (control) administered as two 50 μL intramuscular injections, one in each hind limb, using a 0.5 mL insulin syringe.

Quantifying T-cell responses by ELISpot

ELISpot assays were performed using a mouse interferon-γ (IFN-γ) single color ELISpot kit (Cellular Technology) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.26 27 Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with IFN-γ capture antibody overnight at 4°C. The next day, plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and splenocytes from immunized mice were plated at 500,000 cells/well with no peptide or 10 μg/mL GUCY2C254-262 peptide in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in CTL-TEST medium (Cellular Technology) for 24 hours at 37°C. For T-cell avidity studies, splenocytes were plated at 600,000–800,000 cells/well with decreasing concentrations of GUCY2C254-262 peptide (10 μg/mL to 56 pg/mL) normalized to 106 cells/well.26 27 After incubation, cells were removed, and development reagents were added to detect IFN-γ-producing spot-forming cells. The number of spot-forming cells per well was determined using the SmartCount and Autogate functions of an ImmunoSpot S6 Universal Analyzer (Cellular Technology). GUCY2C-specific responses were calculated by subtracting mean spot counts of 0.1% DMSO wells from peptide-stimulated wells.26 27

Tumor studies

GUCY2C-expressing mouse (BALB/c) CT26 colorectal cancer cells were used for in vivo tumor studies.17 Luciferase-expressing cells were generated by transduction with lentiviral supernatants produced by 293FT cells (Invitrogen) with pLenti4-V5-GW-luciferase.28 For tumor experiments, BALB/cJ mice were immunized with 1010 vp of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1, Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1, or PBS (control) 7 days before delivering 5×105 CT26 cells into tail veins. Tumor burden was quantified weekly by subcutaneous injection of 3.75 mg of D-luciferin potassium salt (Gold Biotechnologies) in PBS followed by an 8 min incubation and imaging with a 10 s exposure using a Caliper IVIS Lumina XR imaging station (PerkinElmer). Total radiance (photons/second) was measured using Living Image In Vivo Imaging Software (PerkinElmer).

Antibody neutralization assay

Serum samples were obtained previously from patients before immunization with Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE (NCT01972737) approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Review Board.21 Neutralizing antibody titers against Ad5 and Ad5.F35 vectors were quantified as described.21 Briefly, dilutions of heat-inactivated serum samples were added to 96-well tissue culture plates containing 105 A549 cells (ATCC) and infected with 108 vp of GFP-expressing Ad5 or Ad5.F35 virus (Ad5-CMV-eGFP or Ad5.F35-CMV-eGFP, respectively; Baylor Vector Development Lab). Following a 41-hour incubation at 37°C, eGFP fluorescence (490 nm excitation, 510 nm emission) was quantified using a POLARstar Optimate plate reader (BMG Labtech). Sample fluorescence was normalized to control wells containing cells and virus (0% neutralization) or wells containing cells alone (100% neutralization). Titers were quantified using non-linear regression as the serum dilution producing 50% neutralization (Prism v8, GraphPad Software).

Ad5 neutralizing immunity studies

To induce anti-Ad5 immunity, mice were exposed intranasally to 1010 Ad5-GFP once or twice at a 4-week interval. Thirty days after the last exposure, Ad5 NAbs were quantified in sera as described above and mice were immunized intramuscularly with 1011 vp of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 or Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1.

Biodistribution and toxicology study

BALB/cJ mice were immunized intramuscularly with a single dose of 1011 vp of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1, three doses of 1011 vp of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 at 28-day intervals, or PBS (control). Animals were monitored for adverse events once daily with additional evaluations on the day of dosing (5 min, 1 hour, and 3 hours after dosing). On days 14 and 90, designated animals were sacrificed and brain, salivary glands, stomach, small intestine, colon, heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, and injection site were harvested and weighed for histopathological analysis by a blinded pathologist (pathology evaluation was performed by IDEXX BioAnalytics) and detection of viral DNA by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using the previously described assay for the GUCY2C transgene.19 Also, spleens were collected for histopathological analysis and detection of viral DNA as described above, as well as quantification of GUCY2C-specific T-cell responses by IFN-γ ELISpot as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism Software v8. Statistical significance was considered as follows: ns=p >0.05, * p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001, and ****p <0.0001. Cohort sizes were powered based on prior studies with β=0.2 and α=0.05. For multiple comparisons of survival outcomes, significance thresholds were corrected using the Bonferroni method. To identify vaccine-induced T-cell responders and non-responders, a previously described21 modified distribution-free resampling approach was employed and positive T-cell responses were defined as 2× compared with DMSO and >20-specific spots/106 cells. To determine the impact of gender and number of vaccinations on responses, log-transformed vaccine response magnitude was compared in mice of different genders, cohorts, and treatment regimens for up to three-way interactions, with stepwise backward variable selection by Akaike information criterion using R29 package MASS.30

Results

Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 and Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 vectors

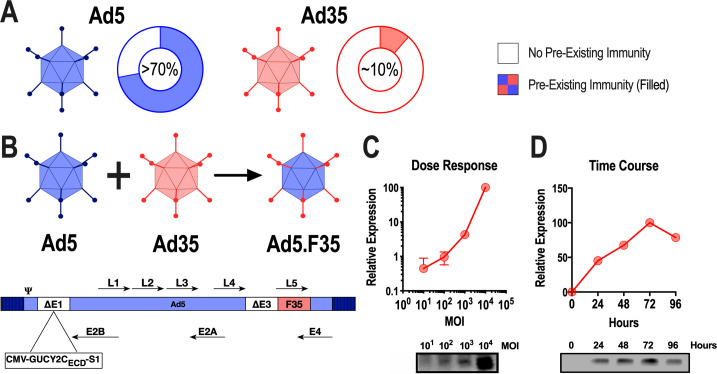

While Ad5 seroprevalence worldwide exceeds 70% (>90% in some regions), Ad35 is ~10% and associated with lower titers (figure 1A).12 31 Thus, we constructed a chimeric adenovirus (Ad5.F35) composed of Ad5 in which the fiber was replaced by the Ad35 fiber and evaluated its ability to induce GUCY2C-specific immunity and resist Ad5-specific immunity in humans and mice. Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 is a replication-deficient human Ad5 expressing the mouse GUCY2C extracellular domain fused to the I-Ed-restricted CD4+ epitope known as site 1 at its C-terminus.20 To generate Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1, the Ad5 fiber (L5) was replaced with the Ad35 fiber (figure 1B). Replication-deficient Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 and Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 generated in HEK293 cells produced dose-dependent (figure 1C) and time-dependent (figure 1D) expression of GUCY2C-S1 protein in A549 human alveolar basal epithelial cells in vitro.

Figure 1.

Construction of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 and antigen expression. (A) Reported international seroprevalence of Ad5 and Ad35.12 (B) The L5 gene encoding the fiber protein from Ad5 was replaced with the L5 gene from Ad35, producing the chimeric adenoviral vector Ad5.F35. Recombinant Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 was produced by inserting mouse GUCY2C-S1 into the E1 region of E1/E3 deleted Ad5.F35. (C and D) The human alveolar basal epithelial cell line, A549, was transduced in duplicate with Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) from 0 to 10,000 for 48 hours (C) or at an MOI of 10,000 for 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours (D). Supernatants from infected cells were analyzed for GUCY2C-S1 protein expression by immunoblot. Protein expression was quantified by densitometry and plotted relative to uninfected cells. Error bars indicate mean±SEM. Ad5, adenovirus serotype 5.

Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 induces GUCY2C-specific antitumor immunity

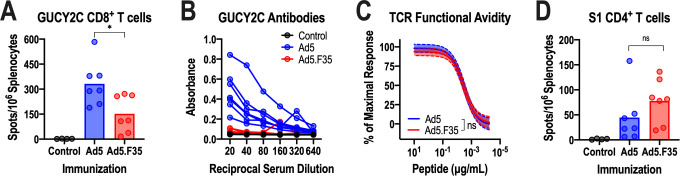

Following in vitro validation of GUCY2C expression by Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1, we confirmed its ability to induce GUCY2C-specific immune responses after vaccination in vivo. BALB/c mice immunized intramuscularly with 1010 vp of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 produced 54% lower GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T-cell responses (figure 2A), and no GUCY2C-specific antibody responses (figure 2B), compared with Ad5-GUCY2C-S1. Importantly, Ad5 and Ad5.F35 vaccines produced GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T cells of comparable avidity (figure 2C), a critical determinant of the antitumor efficacy of GUCY2C-targeted vaccines.26 In contrast, GUCY2C-specific antibody responses have no detectable antitumor activity.20 32 Similarly, Ad5 and Ad5.F35 vaccines produced comparable S1-specific CD4+ T-cell responses (figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Immunogenicity of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 and Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1. (A–D) BALB/c mice (n=4–7 mice/group) were immunized intramuscularly with control or 1010 vp of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 or Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 and serum and splenocytes were collected 14 days later. GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were quantified by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) ELISpot (A) and antibodies were quantified by ELISA (B). (C) GUCY2C-specific T-cell avidity measurements were analyzed by ELISpot using non-linear regression (log(agonist) versus normalized response) with comparisons made using the extra sum-of-squares F test. Avidity plots depict the regression line (solid) with 95% CIs (dashed). (D) S1-specific CD4+ T-cell responses were measured by IFN-γ ELISpot. T-cell responses in (A) and (D) were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Values in (A), (B), and (D) indicate individual animals, and bars in (A) and (D) indicate means. TCR, T-cell receptor; Ad5, adenovirus serotype 5.

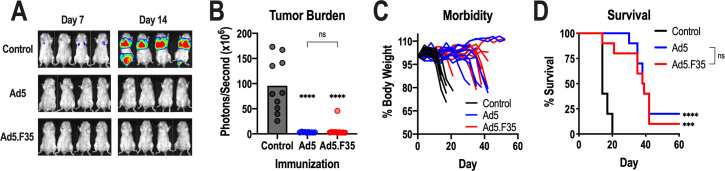

Previous studies revealed that Ad5-GUCY2C vaccines induced protective antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses in murine models of metastatic colorectal cancer.17–20 25 26 Thus, BALB/c mice were immunized with Ad5 or Ad5.F35 expressing GUCY2C-S1 and challenged 7 days later with CT26 colorectal cancer cells expressing GUCY2C and firefly luciferase. This model specifically emulates secondary prevention of metastatic disease, the clinical setting for which the GUCY2C vaccine is being developed.21 As previously demonstrated, Ad5 vaccination nearly eliminated metastatic tumor burden (figure 3A, B), delayed disease progression (figure 3C), and improved survival (figure 3D). Similarly, Ad5.F35 also reduced tumor burden (figure 3A, B), disease progression (figure 3C), and prolonged survival (figure 3D). Importantly, the efficacy of Ad5-based and Ad5.F35-based GUCY2C vaccines in reducing tumor burden, opposing disease progression, and promoting survival was identical (figure 3A–D).

Figure 3.

Antitumor efficacy of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 and Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1. (A–D) BALB/c mice (n=10 mice/group) were immunized intramuscularly with control or 1010 vp of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 or Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 and challenged 7 days later with a mouse colorectal cancer cell line, CT26, expressing GUCY2C and luciferase. On days 7 and 14 following challenge, mice were injected with D-luciferin and imaged (A) to quantify tumor burden (day 14; B). Mice were weighed twice weekly (C) and monitored for survival (D). Tumor burden (B) was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance and survival comparisons (D) were analyzed by the Mantel-Cox log-rank test. In (B) and (D), asterisks (*) indicate comparisons of GUCY2C vaccines to the control and brackets (]) indicate comparisons between Ad5 and Ad5.F35 vaccines. ns, not significant; Ad5, adenovirus serotype 5.

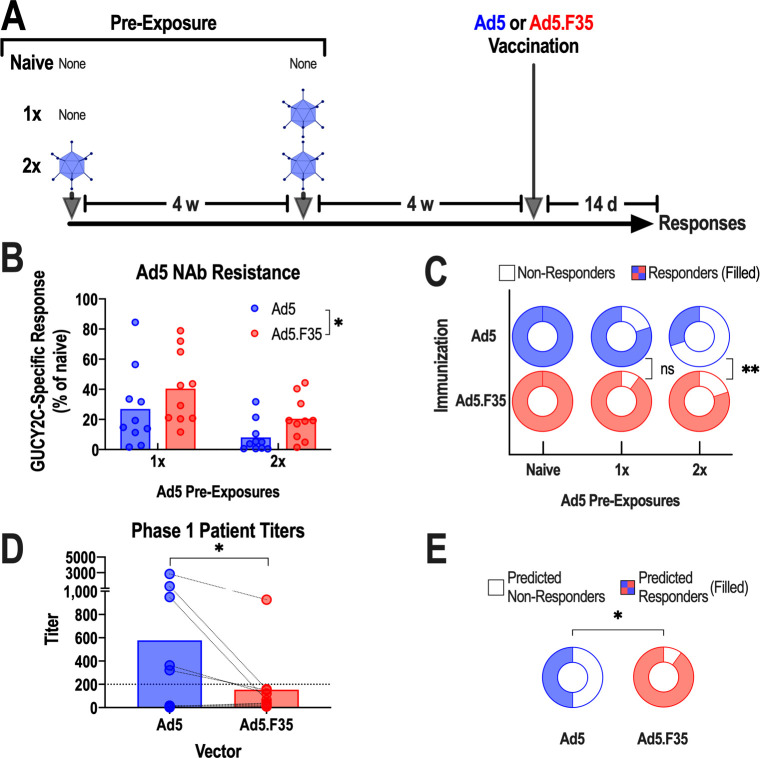

Ad5.F35 resists Ad5-directed immunity in mice and humans

NAbs against Ad5 correlated with poor GUCY2C-specific immune responses in patients receiving Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE vaccination, and prior exposure of mice to Ad5 similarly blunted vaccine-induced immunity.21 Ad5.F35-based vaccine resistance to pre-existing Ad5 immunity was quantified in a model of respiratory pre-exposure to Ad5, the natural route of infection in patients,33 followed by vaccination and quantification of GUCY2C-specific T-cell responses. Control mice (not pre-exposed to Ad5; naive) and those that were pre-exposed once (1×) or twice (2×) to intranasal Ad5 were vaccinated after 4 weeks with intramuscular Ad5 or Ad5.F35 expressing GUCY2C-S1, and immune responses were quantified 2 weeks later (figure 4A). As expected, one Ad5 pre-exposure induced moderate (<1:200) Ad5 NAbs (online supplementary figure S1) and reduced GUCY2C-specific T-cell responses ~75%, while two pre-exposures induced high (>1:200) Ad5 NAbs (online supplementary figure S1) and reduced GUCY2C-specific T-cell responses >90% following Ad5 vaccination (figure 4B). In contrast, GUCY2C-specific T-cell responses were reduced only 60% (1× pre-exposure) and 80% (2× pre-exposure) following Ad5.F35 vaccination (figure 4B). Importantly, Ad5.F35 produced T-cell responses in a substantially greater fraction of the population (80% cohort responses), compared with Ad5 (30% cohort responses), following serial pre-exposures to Ad5 (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Ad5.F35 resists neutralization associated with pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity in mice and humans. (A–C) To generate pre-existing immunity to Ad5, BALB/c mice (n=10 mice/group) were exposed intranasally once or twice to 1010 vp of Ad5-GFP at 4-week intervals. Four weeks after the final Ad5-GFP exposure, Ad5-exposed and naive mice were immunized intramuscularly with 1011 vp of Ad5-GUCY2C-S1 or Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1. (B), Two weeks after immunization, GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in each group were quantified by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) ELISpot and calculated as the % of mean responses in naive mice. Values indicate individual animals and bars indicate means. Ad5 and Ad5.F35 were compared by two-way analysis of variance. (C) The fraction of animals producing a detectable GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T-cell response (filled regions) in naive, 1×, and 2× Ad5-exposed mice was determined from (B). (D and E) Sera from 10 patients with colorectal cancer collected prior to Ad5.GUCY2C-PADRE vaccination were tested for the ability to neutralize Ad5 and Ad5.F35 vectors and titers were quantified (D; analyzed by paired t-test). The dotted line indicates a titer of 200, the threshold for high neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers.21 (E) While 5/10 subjects had high NAb titers (>200) against Ad5, only 1/10 had high titers to Ad5.F35 vector (filled regions; binomial test). Ad5, adenovirus serotype 5.

jitc-2020-001046supp001.pdf (4.7MB, pdf)

These observations in mice were recapitulated using sera from patients with colorectal cancer in the Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE phase I trial (NCT01972737).21 Here, NAb titers against Ad5 and Ad5.F35 were quantified using an established Ad5/Ad5.F35 reporter virus inhibition bioassay in serum samples collected prior to vaccination with Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE.21 In these patients, Ad5.F35-specific NAb titers were substantially lower than Ad5-specific titers (figure 4D). Most importantly, 50% of patients possessed low (<1:200) Ad5 NAbs titers (figure 4D, E) which closely correlated with a 40% GUCY2C-specific response rate.21 In striking contrast, 90% had low Ad5.F35 NAb titers, suggesting that the vast majority of patients immunized with Ad5.F35-based vaccines could produce GUCY2C-specific responses (figure 4E). Collectively, these observations suggest that pre-existing viral immunity induced by repeated environmental exposures which neutralizes Ad5 delivery platforms may be overcome by the chimeric Ad5.F35 vector to enhance fractional population vaccine responses.

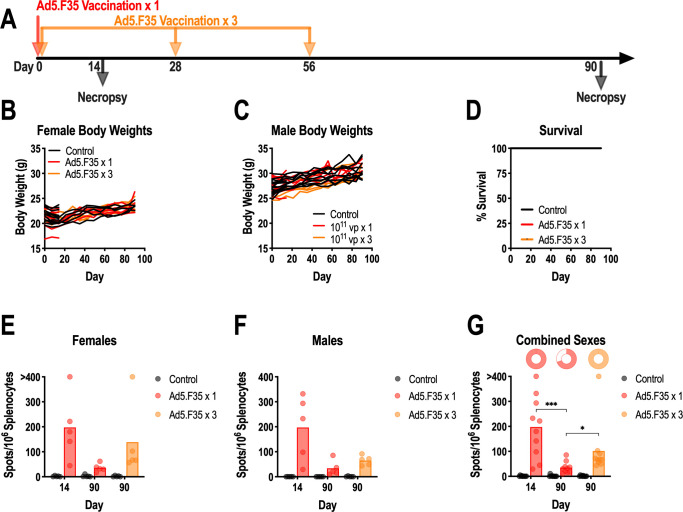

Safety, biodistribution, and toxicity of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1

Food and Drug Administration IND (Investigational New Drug)-enabling studies quantified the toxicity, biodistribution, and immunogenicity of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 in BALB/c mice, employing three schemes to examine acute and chronic effects (figure 5A). Cohorts, balanced for sex, received 1011 Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 either as a single intramuscular injection or as three intramuscular injections spaced 4 weeks apart, monitored daily, and sacrificed on day 14 or 90 for analysis, as indicated (figure 5A). There were no signs of acute or chronic toxicity in the in-life phase by observation, weight changes, or survival (figure 5B–D). Similarly, there were no clinically significant differences in organ weights (online supplementary figure S2) or histopathology (not shown) at necropsy. Small statistical differences in organ weights were considered clinically insignificant and were unrelated to vaccine exposure (dose, time) (online supplementary figure S2). Biodistribution, quantified by qPCR, detected Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 at the injection site and in the spleen, but not appreciably in other organs, after acute and chronic exposures (online supplementary figure S3). Moreover, robust CD8+ T-cell responses were quantified at day 14 that persisted through day 90 in 70% of mice after a single administration (figure 5E–G). As expected, CD8+ T-cell responses were greater, and persisted in more mice (100%), at 90 days after three vaccinations (figure 5E–G).

Figure 5.

Safety and immunogenicity of multiple Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 administrations. (A–G) BALB/c mice (n=10 mice/group) were immunized intramuscularly with one or three administrations of 1011 vp Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1 or control at 4-week intervals. Following immunization, body weights ((B), female and (C) male)) were recorded weekly and mice were monitored for survival (D). At days 14 and 90 following first immunization, mice were euthanized to quantify organ pathology by weight (online supplementary figure S2), biodistribution by quantitative PCR (online supplementary figure S3), and GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T-cell responses by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) ELISpot (E–G). (G) Pie charts indicate proportion of responding animals. Ad5, adenovirus serotype 5.

Discussion

Through decades of gene therapy trials, Ad5 has remained a popular vector, while high Ad5 seroprevalence remains a barrier to universal vaccination.33 Natural respiratory infection can generate long-lived antibodies that neutralize Ad5-based vaccines, eliminating transgene delivery and potential therapeutic benefit. In that context, Ad5 seroprevalence is >70% across multiple countries,12 highlighting an unmet need for alternative vectors. Here, we demonstrate that the chimeric Ad5.F35 resists pre-existing Ad5 immunity and induces transgene-specific antitumor immunity. Indeed, Ad5.F35 is less susceptible to neutralization associated with Ad5 exposure in mice and humans and generates a substantially higher proportion of vaccine responders in mice pre-exposed to Ad5. These observations support the suggestion that Ad5.F35 will produce a higher proportion of vaccine responders in patient populations.

The extent to which NAbs to the Ad5 fiber limit reinfection is controversial. In some studies, replacing the Ad5 fiber with that of another serotype circumvents pre-existing Ad5 immunity.34 In contrast, other studies suggest that these chimeric adenoviruses do not evade pre-existing Ad5 NAbs, suggesting the hexon as the major target of antibody neutralization.35 36 In contrast to those previous studies, which generated pre-existing Ad5 immunity by intramuscular35 or intravenous administration,36 here Ad5 immunity was induced by intranasal exposure in mice, recapitulating natural human respiratory infection.33 Moreover, natural pre-existing Ad5 NAbs in patients with colorectal cancer, uniformly produced by repeated respiratory infections,33 similarly were overcome by the Ad5.F35 vector. Importantly, the quality of antibody responses following adenovirus infection is dependent on the route of exposure. Indeed, respiratory infections elicit fiber-specific NAbs while intramuscular exposure induce capsid-specific NAbs.15 These qualitative differences in NAb responses, reflecting varying routes of immunization, may contribute to observational discrepancies between laboratories. The present studies, using relevant animal models, confirmed and validated with patient samples, support the suggestion that Ad5.F35-based vaccines should produce clinically relevant immune responses in a substantial (~90%) proportion of patients.

Recognizing the pervasive limitations imposed by endemic Ad5 immunity in global populations,12 there is an emerging interest in alternative serotypes and chimeric constructs as a tractable strategy in vaccine development. Ad26, Ad35, and Ad48 vectors have been advanced into phase I clinical trials.37 38 In that regard, a comparison of Ad5, Ad26, Ad35, and Ad48 immunity among healthy patients revealed that endemic Ad35 seropositivity was lowest across global populations,12 reinforcing chimeric strategies employed herein. Similarly, the first hexon-chimeric adenovirus, comprising Ad5 and Ad48 components, was safe and immunogenic in patients.39 Interestingly, Ad5-Ad35 chimeric vectors more efficiently transduce a variety of human cell types in vitro compared with either parental vector.40 These observations underscore the future potential of intelligently designed chimeric adenoviruses strategically constructed to deliver transgenes for replacement therapy or vaccination and targeted precisely to the cellular or disease context.40

While antitumor efficacy was equivalent, CD8+ T-cell responses were lower, and antibody responses were absent, for Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-S1, compared with Ad5-GUCY2C-S1. However, the antitumor efficacy of GUCY2C-directed immunotherapy is driven primarily by T-cell avidity, rather than effector T-cell quantity.26 In that context, the functional avidity of GUCY2C-specific CD8+ T cells following Ad5 and Ad5.F35 immunizations were equivalent, consistent with their comparable antitumor efficacy. Quantitative differences in transgene-specific immunity between vectors may reflect a variety of factors. Thus, the quantity and persistence of GUCY2C-S1 transgene following Ad5.F35 immunization is lower compared with Ad5,19 consistent with prior observations that Ad5 transduction efficiency in vivo may be several-fold higher than Ad5.F35.41 Moreover, the Ad5 fiber binds to CXADR (coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor)42 while the Ad35 fiber binds to CD46,43 suggesting the two viruses may infect distinct cell types.

While checkpoint inhibitors have generated practice-shifting results in the clinic and defined immunotherapy as an effective strategy for the treatment of several malignancies, they have not been universally successful. In that context, the dearth of neoepitopes in many cancer types, including microsatellite stable colorectal and pancreatic (second and third leading causes of cancer mortality, respectively), makes them insensitive to checkpoint blockade.7 Indeed, examination of neoepitopes presented on the surface of five colorectal cancer specimens revealed a total of three neoepitopes.3 Thus, vaccines targeting cancer-associated self-antigens have re-emerged, alone and in combination with checkpoint inhibitors, as a strategy to prevent and treat metastases from these cold tumors.44 45

Checkpoint inhibitors have become first-line therapy in the metastatic setting for some cancers,46 while chimeric antigen receptor expressing T cells (CAR-T cells) are being deployed in patients with metastatic and refractory disease.47 48 In contrast, few cancer immunotherapies have been developed for early-stage cancer patients with “no evidence of disease” (NED) following conventional surgical/radio/chemotherapies, who are at significant risk of disease recurrence. Indeed,~25% of stage II, and ~50% of stage III, patients with colorectal cancer recur following surgery and chemotherapy,49 while 70% of patients with resectable pancreatic cancer experience recurrence.50 Vaccines targeting tumor-associated antigens, such as Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-PADRE, may provide safe and effective immunotherapies for the secondary prevention of metastatic disease in patients with NED who are otherwise ineligible to receive checkpoint inhibitors or CAR-T cells.

The present studies suggest that the chimeric adenoviral vector Ad5.F35 may be preferable to the widely used Ad5 vector and warrants further investigation. Indeed, they suggest that ongoing clinical investigations of GUCY2C-directed immunotherapy in patients with GUCY2C-expressing cancers, including colorectal, pancreatic, gastric, and esophageal, could benefit from using the Ad5.F35, rather than the Ad5, vector. In that context, an upcoming clinical trial will examine the safety, immunogenicity, and resistance to pre-existing immunity of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-PADRE in patients with GI cancer (NCT04111172). Safe generation of GUCY2C-targeted immunity in a high proportion of patients will lead to efficacy trials to establish the ability of Ad5.F35-GUCY2C-PADRE to prevent recurrence following standard therapy in patients with GI cancer, who represent 25% of all cancer deaths51 and for whom established immunotherapies are ineffective.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Adrian P Gee, PhD, Zhuyong Mei, MD, Deborah Lyon, and Malcolm Brenner, MD, PhD (Center for Cell and Gene Therapy, Baylor College of Medicine) for assistance in vaccine manufacturing.

Footnotes

Twitter: @adamsnookphd

JCF and JS contributed equally.

Contributors: JCF, JS, BB, SAW, and AES designed the studies. JCF, JS, RC, EL, TRB, JB, EC, AP, JAR, and JR carried out the studies. TZ carried out data analysis and statistical analysis in discussion with AES. JCF and AES wrote the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 CA204881, R01 CA206026, and P30 CA56036), the Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program W81XWH-17-PRCRP-TTSA, and Targeted Diagnostic & Therapeutics to SAW. AES received a Research Starter Grant in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics from the PhRMA Foundation, a DeGregorio Family Foundation Award, and was supported by the Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (nos W81XWH-17-1-0299, W81XWH-19-1-0263, and W81XWH-19-1-0067). SAW and AES were also supported by a grant from The Courtney Ann Diacont Memorial Foundation. JCF is supported by the Alfred W. and Mignon Dubbs Fellowship Fund and a PhRMA Foundation Pre-Doctoral Fellowship In Pharmacology/Toxicology. JB is supported by a PhRMA Foundation Pre-Doctoral Fellowship in Pharmacology/Toxicology. EC and BB were supported by NIH institutional award T32 GM008562 for Postdoctoral Training in Clinical Pharmacology. AP was supported by a Ruth Kirschstein Individual Research Fellowship Award (F31 CA225123). JAR was supported by a PhRMA Predoctoral Fellowship Award in Pharmacology/Toxicology and an NIH Ruth Kirschstein Individual Predoctoral MD/PhD Fellowship (F30 CA232469). SAW is the Samuel M.V. Hamilton Professor of Thomas Jefferson University. This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (SAP no. 4100051723). The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Research reported in this publication utilized the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at Jefferson Health and was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under Award Number 5P30CA056036-20.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Competing interests: SAW is the Chair of the Scientific Advisory Board and member of the Board of Directors of, and AES is a consultant for, Targeted Diagnostics and Therapeutics, which provided research funding that, in part, supported this work and has a license to commercialize inventions related to this work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 13S.462) and Institutional Biosafety Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant or Synthetic Nucleic Acid Molecules. All patients provided written informed consent to participate. Animal studies were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. Data and detailed protocols are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Xin Yu J, Hubbard-Lucey VM, Tang J. The global pipeline of cell therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18:821–2. 10.1038/d41573-019-00090-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenstein M. Cellular censuses to guide cancer care. Nature 2019;567:555–7. 10.1038/d41586-019-00904-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newey A, Griffiths B, Michaux J, et al. Immunopeptidomics of colorectal cancer organoids reveals a sparse HLA class I neoantigen landscape and no increase in neoantigens with interferon or MEK-inhibitor treatment. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:309. 10.1186/s40425-019-0769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joyce JA, Fearon DT. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 2015;348:74–80. 10.1126/science.aaa6204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maleki Vareki S. High and low mutational burden tumors versus immunologically hot and cold tumors and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:157. 10.1186/s40425-018-0479-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegde PS, Chen DS. Top 10 challenges in cancer immunotherapy. Immunity 2020;52:17–35. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2500–1. 10.1056/NEJMc1713444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Popovic A, Jaffee EM, Zaidi N. Emerging strategies for combination checkpoint modulators in cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Invest 2018;128:3209–18. 10.1172/JCI120775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019;18:197–218. 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wold WSM, Toth K. Adenovirus vectors for gene therapy, vaccination and cancer gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther 2013;13:421–33. 10.2174/1566523213666131125095046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw AR, Suzuki M. Immunology of adenoviral vectors in cancer therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019;15:418–29. 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barouch DH, Kik SV, Weverling GJ, et al. International seroepidemiology of adenovirus serotypes 5, 26, 35, and 48 in pediatric and adult populations. Vaccine 2011;29:5203–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zak DE, Andersen-Nissen E, Peterson ER, et al. Merck Ad5/HIV induces broad innate immune activation that predicts CD8⁺ T-cell responses but is attenuated by preexisting Ad5 immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E3503–12. 10.1073/pnas.1208972109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElrath MJ, De Rosa SC, Moodie Z, et al. Hiv-1 vaccine-induced immunity in the test-of-concept step study: a case-cohort analysis. Lancet 2008;372:1894–905. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61592-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng C, Gall JGD, Nason M, et al. Differential specificity and immunogenicity of adenovirus type 5 neutralizing antibodies elicited by natural infection or immunization. J Virol 2010;84:630–8. 10.1128/JVI.00866-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu B, Dong J, Wang C, et al. Characteristics of neutralizing antibodies to adenovirus capsid proteins in human and animal sera. Virology 2013;437:118–23. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snook AE, Stafford BJ, Li P, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C-induced immunotherapeutic responses opposing tumor metastases without autoimmunity. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:950–61. 10.1093/jnci/djn178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snook AE, Li P, Stafford BJ, et al. Lineage-Specific T-cell responses to cancer mucosa antigen oppose systemic metastases without mucosal inflammatory disease. Cancer Res 2009;69:3537–44. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snook AE, Baybutt TR, Hyslop T, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 vaccine expressing guanylate cyclase C and the PADRE T-helper epitope. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2016;27:238–50. 10.1089/hgtb.2016.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snook AE, Magee MS, Schulz S, et al. Selective antigen-specific CD4(+) T-cell, but not CD8(+) T- or B-cell, tolerance corrupts cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol 2014;44:1956–66. 10.1002/eji.201444539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snook AE, Baybutt TR, Xiang B, et al. Split tolerance permits safe Ad5-GUCY2C-PADRE vaccine-induced T-cell responses in colon cancer patients. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:104. 10.1186/s40425-019-0576-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nilsson M, Ljungberg J, Richter J, et al. Development of an adenoviral vector system with adenovirus serotype 35 tropism; efficient transient gene transfer into primary malignant hematopoietic cells. J Gene Med 2004;6:631–41. 10.1002/jgm.543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valentino MA, Lin JE, Snook AE, et al. A uroguanylin-GUCY2C endocrine axis regulates feeding in mice. J Clin Invest 2011;121:3578–88. 10.1172/JCI57925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magee MS, Kraft CL, Abraham TS, et al. GUCY2C-directed CAR-T cells oppose colorectal cancer metastases without autoimmunity. Oncoimmunology 2016;5:e1227897. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1227897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snook AE, Magee MS, Marszalowicz GP, et al. Epitope-targeted cytotoxic T cells mediate lineage-specific antitumor efficacy induced by the cancer mucosa antigen GUCY2C. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61:713–23. 10.1007/s00262-011-1133-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang B, Baybutt TR, Berman-Booty L, et al. Prime-Boost Immunization Eliminates Metastatic Colorectal Cancer by Producing High-Avidity Effector CD8+ T Cells. J Immunol 2017;198:3507–14. 10.4049/jimmunol.1502672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham TS, Flickinger JC, Waldman SA, et al. Tcr Retrogenic mice as a model to map self-tolerance mechanisms to the cancer mucosa antigen GUCY2C. J Immunol 2019;202:1301–10. 10.4049/jimmunol.1801206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magee MS, Abraham TS, Baybutt TR, et al. Human GUCY2C-targeted chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-expressing T cells eliminate colorectal cancer metastases. Cancer Immunol Res 2018;6:509–16. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. computer software. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern applied statistics with S. 4th edn New York, NY: Springer New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nwanegbo E, Vardas E, Gao W, et al. Prevalence of neutralizing antibodies to adenoviral serotypes 5 and 35 in the adult populations of the Gambia, South Africa, and the United States. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2004;11:351–7. 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.351-357.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marszalowicz GP, Snook AE, Magee MS, et al. Gucy2C lysosomotropic endocytosis delivers immunotoxin therapy to metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2014;5:9460–71. 10.18632/oncotarget.2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fausther-Bovendo H, Kobinger GP. Pre-Existing immunity against AD vectors: humoral, cellular, and innate response, what's important? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:2875–84. 10.4161/hv.29594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xin K-Q, Jounai N, Someya K, et al. Prime-Boost vaccination with plasmid DNA and a chimeric adenovirus type 5 vector with type 35 fiber induces protective immunity against HIV. Gene Ther 2005;12:1769–77. 10.1038/sj.gt.3302590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumida SM, Truitt DM, Lemckert AAC, et al. Neutralizing antibodies to adenovirus serotype 5 vaccine vectors are directed primarily against the adenovirus hexon protein. J Immunol 2005;174:7179–85. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ophorst OJAE, Kostense S, Goudsmit J, et al. An adenoviral type 5 vector carrying a type 35 fiber as a vaccine vehicle: DC targeting, cross neutralization, and immunogenicity. Vaccine 2004;22:3035–44. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs JD, Bart P-A, Frahm N, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus serotype 35-Vectored HIV-1 vaccine in adenovirus serotype 5 seronegative and seropositive individuals. J AIDS Clin Res 2015;6. 10.4172/2155-6113.1000461. [Epub ahead of print: 23 May 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milligan ID, Gibani MM, Sewell R, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of novel adenovirus type 26- and modified vaccinia Ankara-Vectored Ebola vaccines: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:1610–23. 10.1001/jama.2016.4218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baden LR, Walsh SR, Seaman MS, et al. First-In-Human evaluation of a hexon chimeric adenovirus vector expressing HIV-1 env (IPCAVD 002). J Infect Dis 2014;210:1052–61. 10.1093/infdis/jiu217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker AL, White KM, Lavery CA, et al. Pseudotyping the adenovirus serotype 5 capsid with both the fibre and penton of serotype 35 enhances vascular smooth muscle cell transduction. Gene Ther 2013;20:1158–64. 10.1038/gt.2013.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakurai F, Mizuguchi H, Yamaguchi T, et al. Characterization of in vitro and in vivo gene transfer properties of adenovirus serotype 35 vector. Mol Ther 2003;8:813–21. 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00243-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Droguett G, et al. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 1997;275:1320–3. 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaggar A, Shayakhmetov DM, Lieber A. Cd46 is a cellular receptor for group B adenoviruses. Nat Med 2003;9:1408–12. 10.1038/nm952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romero P, Banchereau J, Bhardwaj N, et al. The human vaccines project: a roadmap for cancer vaccine development. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:ps9. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf0685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finn OJ. The dawn of vaccines for cancer prevention. Nat Rev Immunol 2018;18:183–94. 10.1038/nri.2017.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:439–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park JH, Rivière I, Gonen M, et al. Long-Term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018;378:449–59. 10.1056/NEJMoa1709919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.André T, de Gramont A, Vernerey D, et al. Adjuvant fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin in stage II to III colon cancer: updated 10-year survival and outcomes according to BRAF mutation and mismatch repair status of the mosaic study. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:4176–87. 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. Folfirinox or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2395–406. 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2020-001046supp001.pdf (4.7MB, pdf)