Abstract

Government, researchers, and health professionals have been challenged to model, forecast, and evaluate pandemics time series (e.g. new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19). The main difficulty is the level of novelty imposed by these phenomena. Information from previous epidemics is only partially relevant. Further, the spread is local-dependent, reflecting a number of social, political, economic, and environmental dynamic factors. The present paper aims to provide a relatively simple way to model, forecast, and evaluate the time incidence of a pandemic. The proposed framework makes use of the non-central beta (NCB) probability density function. Specifically, a probabilistic optimisation algorithm searches for the best NCB model of the pandemic, according to the mean square error metric. The resulting model allows one to infer, among others, the general peak date, the ending date, and the total number of cases as well as to compare the level of difficult imposed by the pandemic among territories. Case studies involving COVID-19 incidence time series from countries around the world suggest the usefulness of the proposed framework in comparison with some of the main epidemic models from the literature (e.g. SIR, SIS, SEIR) and established time series formalisms (e.g. exponential smoothing - ETS, autoregressive integrated moving average - ARIMA).

Keywords: Time series, Forecasting, Pandemic models, COVID-19, Optimisation

1. Introduction

Pandemics have been one of the main threats to the sustainable development of territories. Most recently, at December 2019, a number of coronavirus-infected pneumonia (NCIP) cases were recorded in a large metropolitan city in China, Wuhan, caused by infection with a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 [1], named COVID-19 hereafter. Accelerated by human migration, exported cases have been reported in several regions of the world, including Europe, Asia, America, and Oceania [2]. As of 17 August 2020, it was estimated a total of 21,549,706 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 767,158 deaths [3].

To mathematically envelop and predict pandemics spread is an arduous task and obviously offer no guarantee of success. For instance, pandemic incidence time series are sensitive to a number of environmental, social, political, technological, and economic variables. Thus, any variation of the underlying scope might alter the dynamic of the incidence trajectory. Therefore, the summary and forecasts only reflects the current expectations of the analyst in the face of the available history of the pandemic system. These inferences can expressively change when new data are incorporated. Anyway, though essentially limited, pandemic models give organisations the opportunity to promote strategies foreseeing crisis situations. Reallocating resources whether financial or professional can than be optimised. In addition, it favours the development of effective intervention strategies as well as preventive plans for future emerging infectious diseases [4].

In a general way, the predictive models largely evolved since second half of 20th century. They are useful in several fields, like economy, environment, and technology areas. In health, the most fundamental epidemic models, first presented by Kermack and McKendrick [5], are still used as a basis for the majority of new epidemic models [6]. These models have been applied to study diverse areas, like the spread of hepatitis [7], tuberculosis [8], and Dengue [9]. From that, it was introduced compartmental models, now often known by initials such as SIR (for ‘susceptible-infectious-removed’ health states), SEIR (for ‘susceptible-exposed-infectious-removed’), SIS (‘susceptible-infectious-susceptible’), and so on. Sustained oscillations in differential equations-based SIR and related models are frequently described using delay differential equations, periodic forcing terms involving sine or cosine functions, and/or age structure [10]. However, fitting epidemiological models to real data possess significant challenges because most epidemics do not conform to the assumptions underlying the basic models formulation. In particular, populations are rarely spatially homogeneous and disease transmission varies with age and other individual-level factors [11]. Referring COVID-19 pandemic, SEIR variants [12], [13] to predict its chronological incidence according to the preceding time series have been introduced.

In fact, time series forecasting methods relying on historical surveillance data have been proposed in order to detect abnormal behaviour of infectious diseases [14]. Exponential smoothing [15], [16], [17], [18], Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) [19], [20], [21], and Decomposition methods [14], [22] are commonly considered. Multiplicative SARIMA models for quarterly measles infections [23] are also considered. In this line, some authors [24] have compared SARIMA and self-Excited Threshold Autoregressive (SETAR) models when forecasting monthly pneumonia cases. Furthermore, combined approaches [25], [26] and machine learning techniques [27], [28], [29] are also applied in health time series forecasting exercises. In the context of coronavirus, statistical models for MERS-CoV [4], [30] and SARS [31] have been attractive.

Anyway, regardless of the time series formalism taken into account, one can highlight two types of frameworks: the short-term and middle-long-term predictors. Based on the former, Roosa et al. [32] have modelled the number of cases of a disease in Chinese provinces to predict 5, 10, and 15 days ahead via generalised logistic growth, Richards growth, and sub-epidemic wave models, for instance. In addition, it was also introduced an improved adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference model (ANFIS) for the incidence of COVID-19 in China for a 10-day horizon [33]. ARIMA models were in turn proposed to predict COVID-19 daily incidence [34]. Appending COVID-19 forecasting models, based on Convolutional Neural Network, were then proposed [35], for the next day. It must be emphasised that short-term forecasts are useful to assist operational management. On the other hand, middle-long-term frameworks, though more challenging, are paramount to plan and control pandemic intervention processes.

The present paper brings an alternative way to study pandemics in this challenging scenario. A middle-long-term forecasting approach based on the non-central beta (NCB) probability distribution is designed in order to deal with disease time incidence. The framework considers that, regardless of the real trajectory of the pandemic time incidence, at least one cicle of three phases is expected: (i) exponential increasing, (ii) plateau, and then (iii) decreasing. The shape of the proposed model is optimally adjusted to the available incidence time series and then extrapolated to infer the number of daily cases in a time horizon determined by the analyst. Thus, a number of relevant statistics (e.g. the global peak date, the end date, the total number of infected cases, the velocity of occurrence of new cases during Phases (i) and (iii)) can be inferred.

The rest of the paper is divided as follows. Section 2 introduces the insights underlying the proposed approach, highlighting the aforementioned shape phases in the COVID-19 daily incidence time series of thirteen countries around the word. Then, in Section 3, the proposed method is presented in details, with emphasis to the near-optimal fit of the NCB-based model to the available time trajectory of the pandemic daily incidence. Section 4 exhibits the promising performance of the NCB-based models in comparison with alternatives from the literature (SIR, SEIR, SIS, exponential smoothing - ETS, and ARIMA) when modelling and forecasting the COVID-19 daily incidence time series of thirteen countries. Cases involving multiple peaks are also addressed. This section also presents a comparison of the challenge imposed by the COVID-19 in the countries taken into account, via NCB framework. Section 5 brings some concluding remarks.

2. Background

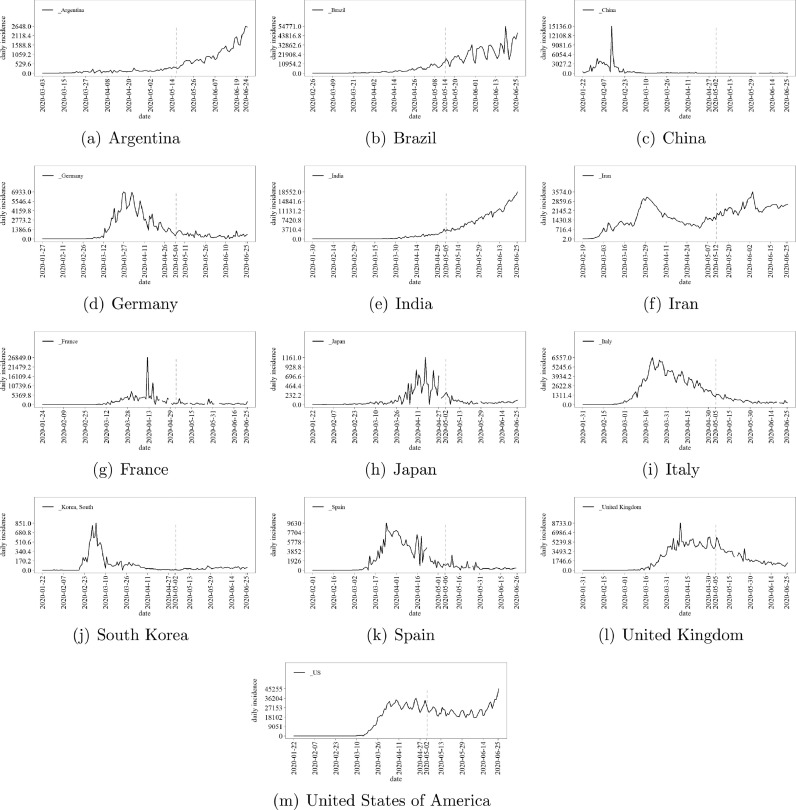

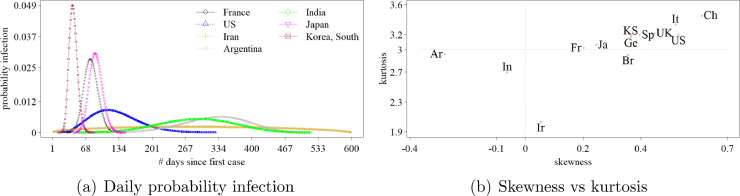

As previously mentioned, regardless of the level of novelty of a given pandemic, it is expected that the shape of the time incidence involves three consecutive phases: (i) exponential increasing, (ii) plateau, and then (iii) decreasing. This dynamic cycle can involve a single or multiple peaks, reflecting viruses mutation, variations on public health intervention policies, technological improvements, and so on (e.g. Spanish flu [36], H1N1 [37], Zika fever [38], Dengue and Chikungunya [38] and COVID-19 [39]). Regarding COVID-19, Fig. 1 sketches the daily incidence in countries around the world until 2020-06-26. The time series are provided by the Johns Hopkins University [40]. One can see that Argentina, Brasil, and India are in Phase (i). In turn, Iran, and States of America-US seem to be transiting between Phases (i) and (iii), involving more than one relevant peak. The remaining countries seem to be in Phase (iii), surmounting the COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

National daily incidence time series since the first register of the COVID-19, according to Johns Hopkins University data set [40].

Specially for the cases in Phase (i), the prediction of the periods in which the virus incidence time series will achieve Phases (ii) and (iii) is a hard task. Common time series formalisms, like ARIMA, ETS, support vector regression, and artificial neural networks [41] are not usually able to predict the plateau-decreasing phases when trained by data sets belonging to Phase (i), only. Further, these approaches suffer when performing relatively middle-long-step-ahead predictions in the light of small sized training data sets. The present paper aims to address these issues by adapting probability density functions that can shape one cycle of Phases (i), (ii), and (iii) even when only data from Phase (i) are available.

3. Proposed framework

The one-cycle exponential increasing-plateau-decreasing shape of pandemics evolution in some territories is also usual to a number of probability density functions (PDFs). In fact, a PDF, say f(x), can not assume negative values and must integrate one [42], leading to exponential decreasing or bounded tails. The NCB family provides a flexible distribution and have wide applications in statistical analysis [43]. It can fit symmetric as well as asymmetric behaviours, also allowing exponential increasing and decreasing shape around a maximum point. Mathematically, the NCB PDF is given by (Nadarajah [44])

| (1) |

in which x ∈ [0, 1] is an instance of the NCB-distributed random variable taken into account (say X), α ( > 0) and β ( > 0) are shape parameters, λ ( ≥ 0) is the non-centrality parameter, and is known as gamma function [42]. When the NCB distribution equals classical beta; otherwise the greater the λ the greater the shift of the mode of X to the right. Thus skewness depends on the combination between λ and the pair (α, β). For instance, taking reflects symmetric distributions, while α > β (α < β) implies in negative (positive) skew. In the case of pandemics, negative (positive) skew reflects the cases in which the time during probability infection increasing (i.e. Phase (i)) is longer (faster) than during probability infection decreasing (Phase (iii)). In other words, negative (positive) skew implies in a Phase (i) longer (faster) than Phase (iii). Therefore, it might be preferred a negative skew, allowing more time to plan and review intervention policies during Phase (i), and presenting a fast decay in the number of new cases during Phase (iii). The values of f( · ) can be easily computed via statistical software like dbetafunction of R [45].

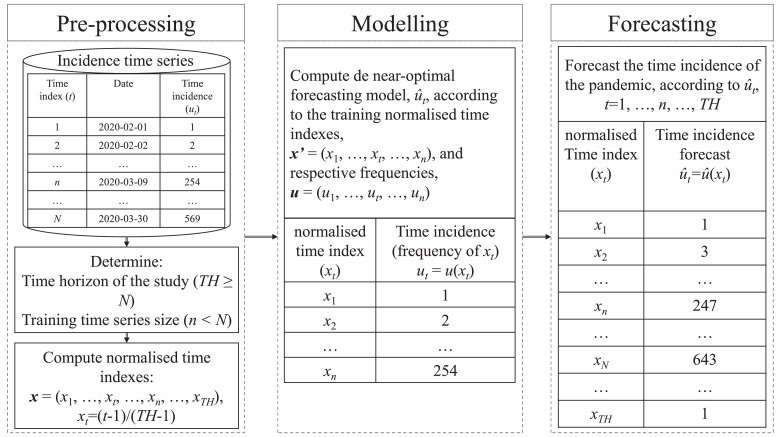

Therefore, the present paper aims to adapt Eq (1) in order to fit the behaviour of an one-cycle pandemic incidence time series. Thus, situations involving multiple local peaks are considered as transient periods, between Phases (i) and (ii) or between Phases (ii) and (iii). It is claimed that though limiting such a reasoning maintains the simplicity of the framework. However, differently from the usual way of adjusting PDFs to a given frequency distribution, it is considered here to fit the time trajectory of the pandemic incidence, via a NCB PDF-based approach. The proposed framework is summarised in Fig. 2 . Three steps are considered: Pre-processing, Modelling, and Forecasting. In the pre-processing step, the available incidence time series (of size N), say is firstly partitioned in two sets. The training set involves the first n points, n < N. For instance, based on the training time series, one can compute the cumulative pandemic incidence until instant n, say . On the other hand, the remaining points are left for evaluating the performance of the prediction model. Besides n, the analyst must determine the time horizon of the study, say TH( > N). The resulting NCB model will then forecast the incidence time series from instant 1 to instant TH. Based on TH, the time indexes are normalised in order to allow the use of the NCB PDF. Let the normalised time indexes set be given by in which . Thus, xi ∈ [0, 1].

Fig. 2.

The proposed framework. In the pre-processing step the time indexes (t) are normalised. It allows one to fit the corresponding incidence time series (ut) via a NCP-based model, say in the modelling step. In the forecasting step, the model is used to predict the time series of the pandemic incidence through the time horizon determined by the part of the analyst.

In turn, in the Modelling step, the training set is used to compute the near-optimal NCB model, . Here, each observed time series value ut (with is approached by

| (2) |

in which represents the estimate of the parameter θ in the light of the training set, reflects the length of the interval involving each NCB PDF evaluation, and

| (3) |

is the estimate of the total number of confirmed infected cases in the territory during TH, with . In this way, is the estimate of the cumulative probability P(X ≤ xn). One can notice that Eq. (3) is based on the idea that X reflects the normalised time until contamination. Thus, if Cumn involves the proportion 100 × FX(xn| · )%, then will involve 100%. Finally, Int[z] rounds z to its nearest integer number.

It is worthwhile to mention that Eq (2) infers the expected value of the pandemic incidence in instant t, considering that the total number of cases, occurs until TH. To better explain, let T be the random cumulative time to confirm one infection since the first case date, i.e. . In fact, supposing that the normalised time X follows a NCB distribution, one has the probability estimate of confirming one case between subsequent instants t and : . Thus, supposing a binomial distribution for the random incidence between t and say Ut ~ binomial one has as expected value leading to Eq (2).

Therefore, once one fixes n( < N) and TH( > N), an optimisation method can be adopted in order to achieve the best estimates of the NCB-based predictor parameters (α, β, λ), . The mathematical optimisation problem in this way has the mean square error (MSE) as fitness function to be minimised:

| (4) |

The MSE brings compromise with both accuracy and efficiency [42]. In the present work, the probabilistic optimisation method named generalised simulated annealing (GenSA) [46] is taken into account.

4. COVID-19 Experiments

The NCB-based framework has been considered to model, forecast, and compare COVID-19 daily time series incidence from thirteen countries (Argentina, Brazil, China, Germany, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, France, South Korea, Spain, United Kingdom, and US). The time series have been maintained and daily updated by Johns Hopkins university collaborators [40]. The experiment is divided in two parts. First, the goodness of fit of near-optimal NCB, epidemic models [47] (SEIR, SIR, and SIS), and established time series formalisms (ARIMA [48] and ETS [49]) approaches are compared, according to a number of performance metrics. Then, the NCB is considered for comparing the level of difficulty imposed by COVID-19 to the countries. The computer used to execute the modelling and forecasting exercises is a notebook with Windows 10 Home (64 bits) operational system, Intel i7 processor with 2.6GHz, and 8GB RAM memory. After presenting the design of each experiment, some specific results and comments are introduced in this way.

4.1. Comparing models performance

Table 1 summarises the tuning parameters adopted for achieving the near-optimal NCB, SEIR, SIS, and SIR forecasting models. It must be highlighted that the framework introduced in Section 3 has been adapted (Eq (1)) to SEIR, SIS, and SIR equations. Thus, the NCB, SEIR, SIR, and SIS models were adjusted via least squared estimation method, by minimising Eq (4). The search space of NCB parameters was . In turn, the search space for SIR and SIS parameters was ([1E-10, 100], [1E-06, 100]) for the pair transmission and removed rates, say . Besides and SEIR has also involved the pair per capita death rate and transition rate from exposed to infectious: .

Table 1.

Tuning parameters of the COVID-19 daily incidence models for each country taken into account (Argentina, Brazil, China, Germany, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, France, South Korea, Spain, United Kingdom, and US).

| characteristic | value |

|---|---|

| data percentage for training set | 0.65 |

| TH | 600 |

| GSA.max.call | 3.00E+04 |

| GSA.max.time | 10 |

| GSA.max.it | 5.00E+03 |

| GSA.temperature | 1.00E+08 |

| GSA.nb.stop.improvement | 20 |

| nmodels | 5E+03 |

This optimisation phase has been implemented according to the GenSA package [50] of R. Regarding SEIR, SIR, and SIS, the EpiDynamics package of R [51] has been used. In this way, it was considered that the maximum number of calls of each MSE-based fitness function was (GSA.max.call=) 3E+04, the maximum running time was (GSA.max.time=) 10 seconds, the maximum number of iterations of the algorithm was (GSA.max.it=) 5E+03, the initial value for temperature was (GSA.temperature=) 1E+08, and the algorithm would stop when there were no improvement after (GSA.nb.stop.improvement=) 20 steps.

It was assumed allowing one to predict the daily incidence during 600 days since the first infection. In turn, the size of the training set is

| (5) |

in which the time series size (N) is country-dependent.

Regarding ARIMA and ETS, the forecast package of R [52] was considered. The respective auto.arima and ets functions have also promoted near-optimal ARIMA and ETS models. The maximum number of models considered in the stepwise search was (nmodels=) 5E+03.

Table 2 summarises the time consumption by the part of the models during training and test exercises, per country and on average. One can see that the ARIMA modelling is the cheaper framework, followed by ETS and then NCB. In turn, SIR, SEIR, and SIS have required the maximum allowed time of the GSA optimiser. Tests involving GSA.max.time superior to 10 seconds have not led to expressive changes in the fitted models, though GSA.max.time has been fully consumed by SIR, SEIR, and SIS.

Table 2.

Time consumption (in seconds) for training and testing near-optimal NCB, SIR, SEIR, SIS, ARIMA, and ETS models for each COVID-19 daily incidence time data taken into account (Argentina - Ar, Brazil - Br, China - Ch, France - Fr, Germany - Ge, India - In, Iran - Ir, Italy - It, Japan - Ja, Korea, South - KS, Spain - Sp, United Kingdom - UK, US).

| model | phase | Ar | Br | Ch | Fr | Ge | In | Ir | It | Ja | KS | Sp | UK | US | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCB | training | 3.150 | 2.820 | 3.250 | 3.540 | 2.890 | 3.230 | 3.050 | 2.970 | 2.900 | 3.330 | 2.860 | 2.900 | 2.870 | 3.058 |

| test | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | |

| SIR | training | 10.06 | 10.01 | 10.02 | 10.00 | 10.01 | 10.03 | 10.02 | 10.01 | 10.09 | 10.03 | 10.01 | 10.02 | 10.02 | 10.025 |

| test | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.013 | |

| SEIR | training | 10.04 | 10.01 | 10.02 | 10.01 | 10.00 | 10.02 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.01 | 10.00 | 10.01 | 10.00 | 10.02 | 10.011 |

| test | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.013 | |

| SIS | training | 10.05 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.02 | 10.00 | 10.01 | 10.02 | 10.00 | 10.01 | 10.02 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.010 |

| test | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.011 | |

| ARIMA | training | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.018 |

| test | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | |

| ETS | training | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.045 |

| test | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 |

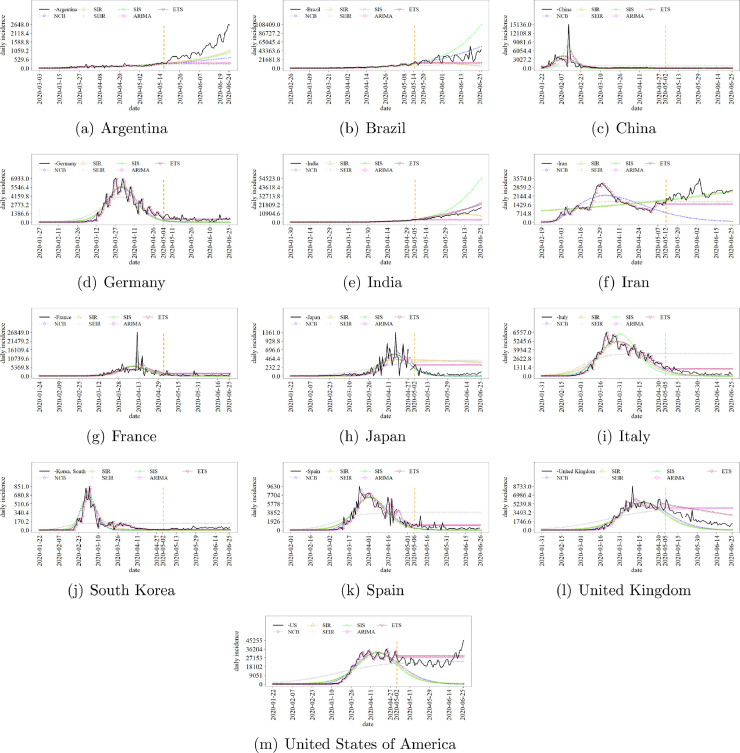

Fig. 3 exhibits the available COVID-19 incidence time series and the respective models forecasts. The vertical orange dashed line separates the training and test data sets. The machine learning has been based on the training set. Then, the predictors were challenged to infer the test series. One can see the difficult of the predictors in fitting the pandemics incidence trajectory though some adherence can be verified. It is argued that any change in the national and local intervention policies might affect the pandemics trajectory, leading to the fluctuations of the target series around the expected values inferred from the models, mainly in the training set. In turn, to predict the incidence trajectory of countries in Phases between (i) and (ii) has been specially intriguing. Anyway, the target has lied between the forecasts bounds, but for the case of Argentina (Fig. 3(a)), in which the target has always been underestimated. Further, the performance of SEIR, ARIMA, and ETS in predicting the transition between Phases (i) and (iii) has usually been precarious. As previously mentioned, ARIMA and ETS might be more useful to perform short-term (e.g. one-step-ahead) than middle-long-term forecasts, thus tending to present small oscillations through the latter. In turn, SEIR has usually predicted the Phase (ii) for the series, though taking Germany, France, and United Kingdom as exceptions. Finally, cases like Iran and US have been particularly tricking once they are transiting between Phases (i) and (iii) in a very peculiar way, suggesting multiple peaks.

Fig. 3.

Prediction of the national daily incidence of COVID-19 since the first register, according to Johns Hopkins University data set [40]. The vertical orange dashed line separates training and test series.

4.1.1. Performance measures

With respect to the quality of the predictors, some performance metrics are considered. In this way, let ut be the incidence of COVID-19 at day t and let be the respective forecast for the target ut. Further, let N be the number of observations of the incidence time series taken into account. Besides MSE, there are a number of metrics for evaluating the discrepancies between ut e for . Here, the following metrics are considered for evaluating the quality of near-optimal NCB, epidemic (i.e. SEIR, SIR, and SIS), and usual time series (i.e. ARIMA and exponential smoothing - ETS) models: MSE; Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE); Average Relative Variance (ARV); Index of Disagreement (ID); Theil’s U (Theil); Wrong Prediction on Change of Direction (WPOCID); Intercept of the linear fit between and ut (Reg_Intercept); Slope Coefficient of the linear fit between and ut (Reg_Slope); Indeterminacy Coefficient of the linear fit between and ut (WR2) [41], [53]; and an Aggregate Performance Metric (APM). See Eqs (4), (6)-(13). The greater the value of a given metric, the worse the model is.

MAPE measures the model accuracy is a relative value:

| (6) |

ARV compares the performance of the predictor with the one of the simple mean of the past values of the series.

| (7) |

in which .

The ID disregards from the measure unit, with values in the interval [0,1]:

| (8) |

Theil’U compares the performance of the predictor with the one of the Random Walk model (in which ut is inferred by ):

| (9) |

Further, WPOCID measures the model quality in forecasting the tendency of the target time series.

| (10) |

| (11) |

In turn, WR2 = as well as Reg_Intercept and Reg_Slope are related to the linear model adjusted to the pairs ut e via minimal squared estimation. In this way, one can consider the general equation [41]. Thus, Reg_Intercept and Reg_Slope coefficients represent the additive and multiplicative errors of the forecasts of ut, respectively. In this case, there is a constant error Reg_Intercept, independent from the forecast, and a proportional error Reg_Slope related to the prediction [41]. In turn, R 2, the determination coefficient, reflects the performance of the model in capturing the variability of the time series [41]. R 2 is defined as

| (12) |

in which is the average of the observed series. Thus, an ideal predictor would present WR2 = 0, and leading to, .

In order to provide a general analysis of these metrics, it is considered the aggregate performance metric:

| (13) |

in which n.Metrici is the metrici, from the aforementioned ones, normalised according to its values regarding the models taken into account (i.e. NCB, SEIR, SIR, SIS, ARIMA, and ETS) and m is the number of metrics ( in the present paper, reflecting MSE, MAPE, ARV, ID, Theil’U, WPOCID, and WR2). APM is based on the reasoning that the near to zero the value of APM is, the better the model is. Thus, for APM, and are adopted instead of and . Therefore, APM is the simple average of the normalised version of the previous mentioned metrics, according to

| (14) |

in which mini and maxi are, respectively, the observed minimal and maximal values of Metrici among the adjusted models under study.

For instance, Tables 3 and 4 summarise the performance of the near-optimal predictors when fitting and forecasting COVID-19 incidence in Brazil, in this order. The second and third columns of the tables highlight the model with the worst and best figures, respectively. One can see that NCB has always beaten the remaining models during training, but in terms of MAPE and WPOCID, in which SEIR and ARIMA have been the best, in this order. During test phase, NCB has only been overcome by SIR WPOCID. Thus, under an aggregate point of view (two last lines of the tables), NCB has been attractive. Anyway, the expressive values of MSE reflect the challenge of fitting and predicting this series. On the other hand, the NCB model has been able to capture (R 2 = 1-WR2=) 92.3% of the variability of the Brazilian series during training phase. In turn, NCB has presented a MAPE of 0.377 in the test phase.

Table 3.

Performance of the forecasting models (NCB, SIR, SEIR, SIS, ARIMA, ETS) when predicting Brazil time data (Training phase).

| Metric | Worst | Best | NCB | SIR | SEIR | SIS | ARIMA | ETS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | SEIR | NCB | 826,041.911 | 833,723.367 | 2,482,605.051 | 890,196.949 | 1,024,260.000 | 1,018,379.494 |

| MAPE | SEIR | ETS | 0.980 | 4.567 | 18.219 | 11.650 | 0.356 | 0.342 |

| ARV | SEIR | NCB | 0.085 | 0.087 | 0.430 | 0.093 | 0.115 | 0.116 |

| ID | SEIR | NCB | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.082 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.027 |

| Theil | SEIR | NCB | 0.806 | 0.814 | 2.422 | 0.869 | 1.000 | 0.994 |

| WPOCID | ARIMA | SEIR | 0.436 | 0.436 | 0.423 | 0.436 | 0.590 | 0.564 |

| Reg_Intercept | SEIR | NCB | -3.145 | -30.141 | -1212.965 | -291.635 | 122.712 | 114.103 |

| Reg_Slope | SEIR | NCB | 1.001 | 1.012 | 1.472 | 1.054 | 1.018 | 1.025 |

| WR2 | SEIR | NCB | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.143 | 0.078 | 0.092 | 0.091 |

| n.MSE | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.005 | 1.000 | 0.039 | 0.120 | 0.116 |

| n.MAPE | SEIR | ETS | 0.036 | 0.236 | 1.000 | 0.633 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| n.ARV | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.006 | 1.000 | 0.023 | 0.087 | 0.091 |

| n.ID | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.006 | 1.000 | 0.029 | 0.101 | 0.102 |

| n.Theil | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.005 | 1.000 | 0.039 | 0.120 | 0.116 |

| n.WPOCID | ARIMA | SEIR | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.000 | 0.077 | 1.000 | 0.846 |

| n.Reg_Intercept | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.022 | 1.000 | 0.238 | 0.099 | 0.092 |

| n.Reg_Slope | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.022 | 1.000 | 0.112 | 0.035 | 0.051 |

| n.WR2 | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 0.024 | 0.237 | 0.219 |

| n.Mean | SEIR | NCB | 0.013 | 0.043 | 0.889 | 0.135 | 0.200 | 0.182 |

| n.Sd | SEIR | NCB | 0.027 | 0.076 | 0.333 | 0.199 | 0.307 | 0.256 |

Table 4.

Performance of the forecasting models (NCB, SIR, SEIR, SIS, ARIMA, ETS) when predicting Brazil time data (Test phase).

| Metric | Worst | Best | NCB | SIR | SEIR | SIS | ARIMA | ETS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | SIS | NCB | 111,085,674.372 | 328,439,780.140 | 385,425,251.814 | 910,939,108.023 | 244,592,623.791 | 246,574,546.047 |

| MAPE | SIS | NCB | 0.377 | 0.488 | 0.630 | 0.873 | 0.424 | 0.427 |

| ARV | ARIMA | NCB | 0.571 | 3.368 | 2.814 | 0.709 | 4.884 | 4.823 |

| ID | SIR | NCB | 0.217 | 0.927 | 0.910 | 0.469 | 0.924 | 0.923 |

| Theil | SIS | NCB | 1.250 | 3.707 | 4.333 | 10.303 | 2.764 | 2.786 |

| WPOCID | ARIMA, ETS | SIR | 0.524 | 0.429 | 0.524 | 0.524 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Reg_Intercept | SEIR | NCB | 8878.734 | 47441.944 | -68219.337 | 13930.442 | 24925.791 | 24925.791 |

| Reg_Slope | SEIR | NCB | 0.543 | -2.008 | 11.760 | 0.243 | ||

| WR2 | ARIMA, ETS | NCB | 0.549 | 0.708 | 0.596 | 0.553 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| n.MSE | SIS | NCB | 0.000 | 0.272 | 0.343 | 1.000 | 0.167 | 0.169 |

| n.MAPE | SIS | NCB | 0.000 | 0.225 | 0.511 | 1.000 | 0.096 | 0.102 |

| n.ARV | ARIMA | NCB | 0.000 | 0.649 | 0.520 | 0.032 | 1.000 | 0.986 |

| n.ID | SIR | NCB | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.976 | 0.355 | 0.996 | 0.995 |

| n.Theil | SIS | NCB | 0.000 | 0.271 | 0.341 | 1.000 | 0.167 | 0.170 |

| n.WPOCID | ARIMA, ETS | SIR | 0.167 | 0.000 | 0.167 | 0.167 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| n.Reg_Intercept | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.650 | 1.000 | 0.085 | 0.270 | 0.270 |

| n.Reg_Slope | SEIR | NCB | 0.000 | 0.053 | 1.000 | 0.029 | ||

| n.WR2 | ARIMA, ETS | NCB | 0.000 | 0.354 | 0.103 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| n.Mean | ARIMA | NCB | 0.019 | 0.386 | 0.551 | 0.409 | 0.587 | 0.587 |

| n.Sd | SIS | NCB | 0.056 | 0.322 | 0.357 | 0.456 | 0.443 | 0.439 |

Tables 5 and 6 allow one to compare the performance of the models in the light of the thirteen countries taken into account, in terms of APM. In general, NCB has been the best model whilst it has never been the worst alternative. On the other hand, SEIR has presented precarious performance in comparison with the remaining models, mainly during training phase.

Table 5.

Aggregate mean normalised performance of the forecasting models (NCB, SIR, SEIR, SIS, ARIMA, ETS) when predicting Argentina, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Korea, South, Spain, United Kingdom, US time series (Training phase). The rank of each model is in parentheses, in the last line.

| series | Worst | Best | NCB | SIR | SEIR | SIS | ARIMA | ETS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | SEIR | NCB | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.88 | 0.2 | 0.26 | 0.51 |

| Brazil | SEIR | NCB | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.18 |

| China | SEIR | SIR | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.28 |

| France | ARIMA | NCB | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.72 | 0.09 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Germany | SEIR | NCB | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.96 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| India | SEIR | NCB | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.2 | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| Iran | SIR | ARIMA, ETS | 0.16 | 0.94 | 0.41 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Italy | SEIR | NCB | 0.04 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Japan | SEIR | SIS | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Korea, South | SEIR | SIR | 0.22 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Spain | SEIR | NCB | 0 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| United Kingdom | SEIR | NCB | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.96 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| US | SEIR | ETS | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.93 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| APM (rank) | SEIR | NCB | 0.059 (1) | 0.202 (2) | 0.892 (6) | 0.248 (5) | 0.239 (3) | 0.241 (4) |

Table 6.

Aggregate mean normalised performance of the forecasting models (NCB, SIR, SEIR, SIS, ARIMA, ETS) when predicting Argentina, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Korea, South, Spain, United Kingdom, US time series (Test phase). The rank of each model is in parentheses, in the last line.

| series | Worst | Best | NCB | SIR | SEIR | SIS | ARIMA | ETS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | ARIMA | SIS | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.66 |

| Brazil | ARIMA | NCB | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| China | SEIR | NCB, SIR, SIS | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.26 |

| France | ARIMA | SIS | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Germany | ETS | SEIR | 0.58 | 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.75 |

| India | ARIMA | NCB | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.53 | 0.4 | 0.75 | 0.02 |

| Iran | SEIR | SIS | 0.49 | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| Italy | SEIR | SIR | 0.01 | 0 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| Japan | SEIR | SIS | 0.06 | 0.66 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Korea, South | SEIR | NCB, SIR, SIS | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.6 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.38 |

| Spain | SEIR | SIR | 0.03 | 0 | 0.77 | 0 | 0.41 | 0.51 |

| United Kingdom | ARIMA | NCB | 0 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.4 |

| US | SIS | SEIR | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.36 | 0.37 |

| APM (rank) | ARIMA | NCB | 0.199 (1) | 0.246 (3) | 0.571 (5) | 0.228 (2) | 0.598 (6) | 0.503 (4) |

4.2. Comparing pandemics incidence

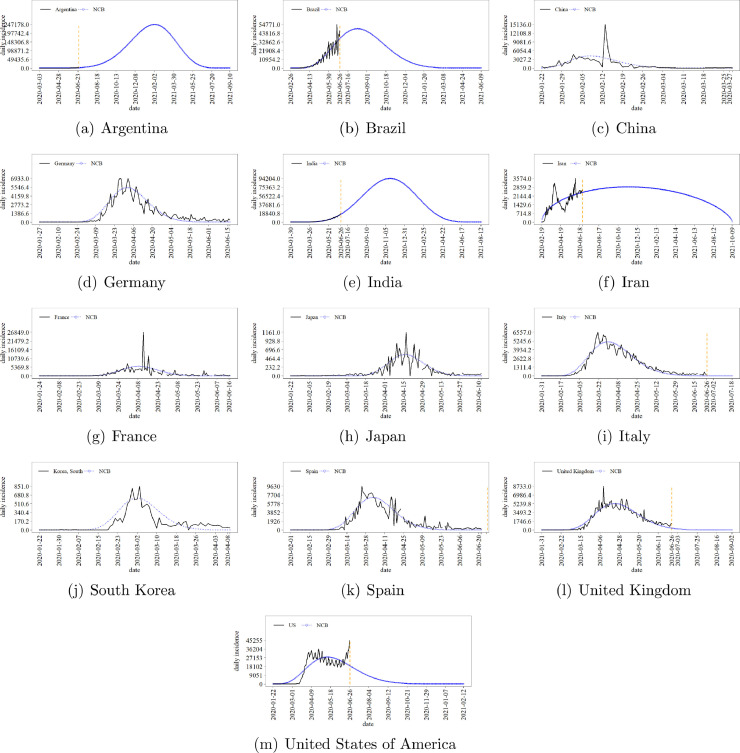

Though evidently limited in the light of multiple-peaks pandemics time series, the proposed NCB approach can be useful for summarising and comparing the difficulty imposed by these diseases among territories. Fig. 4 suggests the time trajectory of the COVID-19 daily incidence taking data until 2020-06-26 as training set for NCB models. Fig. 5 allows one to compare the shape of the NCB models in the face of these national incidence. Table 7 involves specific figures. Besides n and the respective training cumulative incidence (Cumn), the table also exhibits the inferred near-optimal NCB PDF parameters cumulative pandemic incidence through TH days (), and remarkable instants, i.e. the starting (date 0), global peak (datem), and finish (dateend) dates. For instance, until 2020-06-26, the most contaminated country was US, with 2,467,554 infected, followed by Brazil. In turn, considering the available data, it is expected that Argentina assume the worst position until the end of the pandemic, at 2021-09-11, involving a total of 40,676,197 cases. In fact, special attention must also be taken with respect to Argentina and India, which seem to be in the beginning of the pandemic trajectory. The most peculiar NCB shape is dedicated to Iran, with the smallest β estimate and a similar value for α. It is predicted that the global peak in this country would occur near 2020-11-13. Further, though the increasing incidence during the last days in US, the NCB framework estimates that the country is facing Phase (iii). In fact, the proposed NCB approach might not fit multiple-peaks-shaped incidence time series, as it seems to be the case of Iran and US.

Fig. 4.

NCB Prediction of the national daily incidence of COVID-19 since the first register, according to Johns Hopkins University data set [40]. The vertical dashed orange line marks the end of the available time series.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of shapes of the NCB probability distributions, regarding the prediction of the national daily incidence of COVID-19 since the first register, according to Johns Hopkins University data set [40]. In (b), one has the first two letters as mnemonics for Argentina, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, and Spain. In turn, it was considered KS for Korea, South and UK for United Kingdom.

Table 7.

Estimates of the GenSA-based near-optimal NCB models for the national COVID-19 daily incidence time data until 2020-06-26 with respect to Argentina, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, Korea, South - KS, Spain, United Kingdom - UK, and US.

| figure | Argentina | Brazil | China | France | Germany | India | Iran | Italy | Japan | KS | Spain | UK | US |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 116 | 122 | 157 | 155 | 152 | 149 | 129 | 148 | 157 | 157 | 147 | 148 | 157 |

| Cumn | 55,343 | 1,274,974 | 84,726 | 208,215 | 194,036 | 508,953 | 217,724 | 240,109 | 18,632 | 12,653 | 258,311 | 311,355 | 2,467,554 |

| date0 | 2020-03-03 | 2020-02-26 | 2020-01-22 | 2020-01-24 | 2020-01-27 | 2020-01-30 | 2020-02-19 | 2020-01-31 | 2020-01-22 | 2020-01-22 | 2020-02-01 | 2020-01-31 | 2020-01-22 |

| 40,676,197 | 7,325,073 | 84,730 | 208,215 | 194,036 | 18,103,740 | 1,308,410 | 240,174 | 18,632 | 12,653 | 258,312 | 315,874 | 3,238,540 | |

| 1.01 | 6.17 | 1.01 | 2.25 | 19.94 | 5.43 | 1.53 | 9.95 | 36.49 | 23.6 | 17.36 | 11.27 | 5.48 | |

| 13.45 | 15.37 | 302.25 | 320.86 | 155.97 | 9.86 | 1.65 | 82.84 | 238.37 | 323.51 | 144.89 | 65.27 | 20.77 | |

| 31.1 | 0.6 | 18.4 | 90.35 | 0.03 | 8.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 7.83 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0 | |

| datem | 2021-02-03 | 2020-08-09 | 2020-02-08 | 2020-04-08 | 2020-04-01 | 2020-11-18 | 2020-11-13 | 2020-03-30 | 2020-04-16 | 2020-03-02 | 2020-04-02 | 2020-04-23 | 2020-05-12 |

| dateend | 2021-09-11 | 2021-06-10 | 2020-03-28 | 2020-06-17 | 2020-06-17 | 2021-08-14 | 2021-10-10 | 2020-07-19 | 2020-06-12 | 2020-04-09 | 2020-06-22 | 2020-09-03 | 2021-02-13 |

| training time consumption | 6.31 | 3.7 | 4.47 | 4.25 | 3.62 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 4.01 | 3.86 | 3.85 | 3.52 | 3.94 | 4.02 |

Fig. 5 brings the shapes of the COVID-19 national incidence trajectories to the same picture, considering the NCB fitted models. One can thus compare the velocity of the occurrence of new cases (i.e. probability infection) before and after the global plateau phase. For the sake of illustration, from Fig. one can conclude that Korea, South has presented the fastest trajectory during Phases (i), (ii), and (iii), in comparison with France, US, Iran, Argentina, India, and Japan. In turn, it is suggested that US has presented the greatest difference in length of Phases (i) and (iii), i.e. the period in which the probability infection increases is clearly lesser than the period in which the probability infection decreases.

Fig. 5 (b) allows one to compare the thirteen countries in the same terms, via skewness and kurtosis estimates of the fitted NCB probability infection distributions. As previously mentioned, the greater the value of the skew of the probability distribution, in absolute terms, the greater the difference between the lengths of Phases (i) and (iii). On the other hand, the greater the value of the kurtosis the faster the epidemic cycle is. Thus, one can infer that China has presented the fastest cycle, though under the worst difference between the lengths of Phases (i) and (iii). In fact, the duration of Phase (i) was lesser than the one of Phase (iii), thus reflecting the worst scenario for the health system. In turn, Iran would face the longest epidemic cycle, followed by India, Brazil, and Argentina. The similarity of the COVID-19 relative incidence time series in countries like Korea, South and Germany must also be highlighted. It might reflect similar effectiveness of the intervention policies adopted in these countries.

5. Conclusion

Pandemics have been a public health issue for organisations and governments around the world. For instance, COVID-19 has played decisive role for profound culture, economic, and social changes. Thus, predicting and comparing incidence trajectories among territories are paramount. The present paper has provided a relatively simple method for performing these two exercises. It is expected that the proposed NCB approach complements analogous studies at the regional and national level and might be useful in the assessment of plans and emerging disease outbreaks.

Though limited to one-peak shape fitting, the NCB approach has performed better than near-optimal versions of established epidemic models (e.g. SIR, SEIR, SIS) as well as time series formalisms (e.g. ARIMA and ETS) for both fitting previous incidence times series and forecasting future values. The results of the methods with respect to a number of performance metrics underlie this argument. In turn, the NCB probability distribution shape has showed useful for summarising and comparing the pandemic incidence trajectory among countries, via kurtosis and skewness estimates. From that, caution with respect to Iran, Argentina, and China, for the sake of illustration, has been suggested.

The method has showed to be cheap, demanding less than 7 seconds, of an intermediate notebook, to model and forecast the COVID-19 daily incidence in each one of thirteen countries, for a time horizon of 600 days. Thus, considering a database platform that promotes a daily update of the incidence time series (e.g. the Johns Hopkins University [40]), the proposed models can be easily updated. The Pand-Pred user interface, freely provided at www.mesor.com.br, makes use of this reasoning.

A conceptual limitation of the NCB-based framework is the supposition that the incidence of the disease in a given day follows a binomial distribution. Thus, it is considered that one positive diagnostic is independent from another one in that day, something that might disregard from the reality. In addition, the need to set a maximum time horizon for the end of the pandemic cycle may lead to an underestimation of the spread of the disease in the territory. On the other hand, the impossibility of shaping several peaks is a disadvantage of the NCB models. Countries like Iran and the US seem to demand a more flexible approach, in the case of COVID-19. Thus, ongoing research are dedicated to develop modelling alternatives, such as mixtures of PDFs, adapted artificial neural networks, support vector regression, and copulas formalisms.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Paulo Renato Alves Firmino: Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Jair Paulino de Sales: . Jucier Gonçalves Júnior: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Taciana Araújo da Silva: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Brazilian national council for scientific and technological development - CNPq.

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Top N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anzai A., Kobayashi T., Linton N.M., Kinoshita R., Hayashi K., Suzuki A. Assessing the impact of reduced travel on exportation dynamics of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):601. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization W.H.. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 4.Kim Y., Ryu H., Lee S. Agent-based modeling for super-spreading events: acase study of MERS-CoV transmission dynamics in the Republic of Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2369. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kermack W.O., McKendrick A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc R Soc London Ser A, Contain Paper Math Phys Character. 1927;115(772):700–721. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause A.L., Kurowski L., Yawar K., Van Gorder R.A. Stochastic epidemic metapopulation models on networks: SIS dynamics and control strategies. J Theor Biol. 2018;449:35–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahdoust M, Sadeghifar M, Poorolajal J, Javanrooh N, Amini P. Predicting hepatitis B monthly incidence rates using weighted markov chains and time series methods (2015). [PubMed]

- 8.Azeez A., Obaromi D., Odeyemi A., Ndege J., Muntabayi R. Seasonality and trend forecasting of tuberculosis prevalence data in eastern cape, south africa, using a hybrid model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(8):757. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13080757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samat N.A., Percy D.F. 2012 International Conference on Statistics in Science, Business and Engineering (ICSSBE) IEEE; 2012. Dengue disease mapping in malaysia based on stochastic sir models in human populations; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greer M., Saha R., Gogliettino A., Yu C., Zollo-Venecek K. Emergence of oscillations in a simple epidemic model with demographic data. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7(1):191187. doi: 10.1098/rsos.191187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Getz W.M., Dougherty E.R. Discrete stochastic analogs of erlang epidemic models. J Biol Dyn. 2018;12(1):16–38. doi: 10.1080/17513758.2017.1401677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadim SS, Ghosh I, Chattopadhyay J. Short-term predictions and prevention strategies for COVID-2019: A model based study. arXiv preprint arXiv:200308150 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Peng L, Yang W, Zhang D, Zhuge C, Hong L. Epidemic analysis of COVID-19 in China by dynamical modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:200206563 (2020).

- 14.Zhang X., Zhang T., Young A.A., Li X. Applications and comparisons of four time series models in epidemiological surveillance data. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ke G., Hu Y., Huang X., Peng X., Lei M., Huang C. Epidemiological analysis of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China with the seasonal-trend decomposition method and the exponential smoothing model. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39350. doi: 10.1038/srep39350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amini P., Ghaleiha A., Zarean E., Sadeghifar M., Ghaffari M.E., Taslimi Z. Modelling the frequency of depression using holt-winters exponential smoothing method. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2018;12(10) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong D., Pan H., Zheng Y., Jiang C., Han R., Wu H. Application of exponential smoothing model in predicting incidence of scarlet fever in Shanghai. Disease Surveillance. 2019;34(10):932–936. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharwardy S.N., Rahman Z., Sarwar H. 2019 22nd International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT) IEEE; 2019. Time series parameter prediction for ICU patient; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popescu T.D., Alexandru A., Ianculescu M. Assessing and forecasting of epidemiological data using time series analysis. Int J Math Comput Method. 2019;4 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q., Guo N.-N., Han Z.-Y., Zhang Y.-B., Qi S.-X., Xu Y.-G. Application of an autoregressive integrated moving average model for predicting the incidence of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(2):364–370. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q., Liu X., Jiang B., Yang W. Forecasting incidence of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome in China using arima model. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):218. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.González-Parra G., Arenas A.J., Jódar L. Piecewise finite series solutions of seasonal diseases models using multistage adomian method. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2009;14(11):3967–3977. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popescu T.D., Alexandru A., Ianculescu M. Assessing and forecasting of epidemiological data using time series analysis. Int J Math Comput Method. 2019;4 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyamato F.A., Wanjoya A., Mageto T. Comparative analysis of sarima and setar models in predicting pneumonia cases in kenya. Int J Data Sci Anal. 2020;6(1):48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H., Tian C., Wang W., Luo X. Time-series analysis of tuberculosis from 2005 to 2017 in China. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(8):935–939. doi: 10.1017/S0950268818001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi J., Dhall A., Goecke R., Breakspear M., Parker G. Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR2012) IEEE; 2012. Neural-net classification for spatio-temporal descriptor based depression analysis; pp. 2634–2638. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang G., Wei W., Jiang J., Ning C., Chen H., Huang J. Application of a long short-term memory neural network: a burgeoning method of deep learning in forecasting HIV incidence in guangxi, china. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147 doi: 10.1017/S095026881900075X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiens J., Shenoy E.S. Machine learning for healthcare: on the verge of a major shift in healthcare epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(1):149–153. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhagyashree S.I.R., Nagaraj K., Prince M., Fall C.H., Krishna M. Diagnosis of dementia by machine learning methods in epidemiological studies: a pilot exploratory study from south india. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(1):77–86. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1410-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang H.-J. Estimation of basic reproduction number of the middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) during the outbreak in South Korea, 2015. Biomed Eng Online. 2017;16(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12938-017-0370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cori A., Boëlle P.-Y., Thomas G., Leung G.M., Valleron A.-J. Temporal variability and social heterogeneity in disease transmission: the case of sars in Hong Kong. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roosa K., Lee Y., Luo R., Kirpich A., Rothenberg R., Hyman J. Real-time forecasts of the COVID-19 epidemic in China from february 5th to february 24th, 2020. Infect Disease Modell. 2020;5:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-qaness M.A.A., EweesA A.A., Fan H., Aziz M.A.E. Optimization method for forecasting confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):674. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benvenuto D., Giovanetti M., Vassallo L., Angeletti S., Ciccozzi M. Application of the ARIMA model on the COVID-2019 epidemic dataset. Data Brief. 2020:105340. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang C.-J., Chen Y.-H., Ma Y., Kuo P.-H. Multiple-input deep convolutional neural network model for COVID-19 forecasting in China. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chowell G., Nishiura H., Bettencourt L.M. Comparative estimation of the reproduction number for pandemic influenza from daily case notification data. J R Soc Interf. 2007;4(12):155–166. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucero M.G., Inobaya M.T., Nillos L.T., Tan A.G., Arguelles V.L.F., Dureza C.J.C. National influenza surveillance in the Philippines from 2006 to 2012: seasonality and circulating strains. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):762. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2087-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharp T.M., Ryff K.R., Alvarado L., Shieh W.-J., Zaki S.R., Margolis H.S. Surveillance for chikungunya and dengue during the first year of chikungunya virus circulation in puerto rico. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl_5):S475–S481. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferguson N, Laydon D, Nedjati Gilani G, Imai N, Ainslie K, Baguelin M, et al. Report 9: impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand (2020).

- 40.Center for Systems Science and Engineering. Covid-19 data set from the Johns Hopkins University, center for systems science and engineering. 2020. https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19.

- 41.de Mattos Neto P.S., Cavalcanti G.D., Firmino P.R., Silva E.G., Nova Filho S.R.V. A temporal-window framework for modeling and forecasting time series. Knowl Based Syst. 2020:105476. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casella G., Berger R.L. 2nd. Duxbury Pacific Grove, CA; 2002. Statistical inference. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta A.K., Orozco-Castañeda J.M., Nagar D.K. Non-central bivariate beta distribution. Statistic Papers. 2011;52(1):139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nadarajah S. Sums, products, and ratios of non-central beta variables. Commun stat-theory methods. 2005;34(1):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 45.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing; Vienna, Austria; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/.

- 46.Tsallis C., Stariolo D.A. Generalized simulated annealing. Physica A. 1996;233:395–406. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keeling M.J., Rohani P. Princeton University Press; 2008. Modeling infectious diseases in humans and animals. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cryer J.D., Chan K.-S. Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. Time series analysis: with applications in R. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyndman R., Koehler A.B., Ord J.K., Snyder R.D. Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. Forecasting with exponential smoothing: the state space approach. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang Xiang, Gubian S., Suomela B., Hoeng J. Generalized simulated annealing for efficient global optimization: the GenSA package for R. R J Volume 5/1, June 2013. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santos Baquero O., Silveira Marques F.. EpiDynamics: dynamic models in epidemiology; 2020. R package version 0.3.1; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=EpiDynamics.

- 52.Hyndman R., Athanasopoulos G., Bergmeir C., Caceres G., Chhay L., O’Hara-Wild M., et al. forecast: forecasting functions for time series and linear models; 2020. R package version 8.12; http://pkg.robjhyndman.com/forecast.

- 53.Firmino P.R.A., de Mattos Neto P.S., Ferreira T.A. Correcting and combining time series forecasters. Neural Netw. 2014;50:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]