Abstract

Objective

To explore the initial CT features and dynamic evolution of early-stage patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

A total of 126 COVID-19 patients in the early stage were enrolled. The initial CT features and dynamic evolution characteristics of the progression and absorption process from the stage of admission to discharge were retrospectively analyzed in this study.

Results

The main initial CT features were as follows: bilateral distribution (112/126, 88.9%), diffuse distribution (106/126, 84.1%), multiple lesions (117/126, 92.9%), nodular shapes (84/126, 66.7%), patchy shapes (98/126, 77.8%), pure ground-glass opacities (GGO) (95/126, 75.4%), “vascular thickening sign” (98/126, 77.8%), “air bronchogram sign” (70/126, 55.6%), “crazy paving pattern” (93/126, 73.8%), and “pleura parallel sign” (72/126, 57.1%). The main dynamic evolution characteristics were as follows: ① Imaging findings of the progression process: the main CT changes were increased GGOs with consolidation (118/126, 93.7%), an increased “crazy paving pattern” (104/126, 82.5%), an increased “vascular thickening sign” (105/126, 83.3%), and an increased “air bronchogram sign” (95/126, 75.4%); ② Imaging findings of the absorption process: the main CT changes were the obvious absorption of consolidation displayed as inhomogeneous partial GGOs with fibrosis shadows, the occurrence of a “fishing net on trees sign” (45/126, 35.7%), an increased “fibrosis sign” (40/126, 31.7%), an increased “subpleural line sign” (35/126, 27.8%), a decreased “crazy paving pattern” (19.8%), and a decreased “vascular thickening sign” (23.8%); and ③ In the stage of discharge, the main CT manifestations were further absorption of GGOs, consolidation and fibrosis shadows in the lung, and no appearance of new lesions, with only a small amount of shadow with fibrotic streaks and reticulations remaining in some cases (16/126, 12.7%).

Conclusion

The initial CT features and dynamic evolution of early-stage patients with COVID-19 have certain characteristics and regularity; CT of the chest is critical for early detection, evaluation of disease severity and follow-up of patients.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus type 2, COVID-19, Pneumonia, Computed tomography, X-ray computer

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) refers to related diseases caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) with clinical presentation of viral pneumonia [1]. The disease was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [2], before an outbreak occurred worldwide. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated this disease as a global pandemic, and COVID-19 is currently a major infectious disease that seriously threatens human life [3].

Chest CT is an important means of diagnosing and evaluating COVID-19 [4]. We aimed to retrospectively analyze and summarize the chest CT manifestations and dynamic evolution characteristics of patients with COVID-19 in the early stage to further understand the occurrence, development and outcome of this disease and to provide guidance for clinical prevention.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Patients

The data came from the First Affiliated Hospital of the University of Science and Technology of China, and several other designated hospitals qualified for diagnosis and treatment from December 2019 to March 2020. Inclusion criteria were: ① all patients were confirmed cases which were ultimately discharged after being cured, in accordance with “COVID-19 Diagnosis and Treatment Program (Trial Seventh Edition)” published by the National Health Commission of China [5]; ② the first CT results were positive; ③ no patients had a history of any anti-infectious therapy before the first chest CT; and ④ at least three chest CT examinations were carried out during hospitalization. After the exclusion of severe and critical cases and patients with incomplete disease course, 126 patients in the early stage aged from 4 to 78 years old were enrolled in this study (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patient cohort.

| Items | n (%) or Mean ± SD [Range] |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.2 ± 10.8 (4–78) |

| Male | 74 (58.7%) |

| Female | 52 (41.3%) |

| Initial symptoms | |

| Fever | 114 (90.5%) |

| Cough | 108 (85.7%) |

| Fatigue | 65 (51.6%) |

| Pharyngeal discomfort | 25 (19.8%) |

| Nausea | 12 (9.5%) |

| Headache | 10 (7.9%) |

| Chest tightness | 6 (4.8%) |

| Numbers of scans | 6 ± 2 (4–9) |

| The interval between the adjacent scans (days) | 5 ± 1 (1–10) |

| The hospitalized period (days) | 22 ± 5 (12–40) |

2.2. Imaging techniques

All images were obtained on one of the following CT scanners: ① Somaton Definition AS+ (Siemens Healthineers, Germany); ② Neuviz 128 CT (Neuviz Healthcare, China); and ③ Discovery HD 750 and LightSpeed VCT (GE Healthcare, America). The main scanning parameters were as follow: tube voltage = 120 KV; tube current (250 mA −450 mA); pitch (1.0–1.375); spinning speed (0.8 s − 1.0 s), matrix = 512 × 512, slice thickness = 5 mm, FOV = 350 mm × 350 mm. All CT images were reconstructed with a slice thickness and increment of 1.25 mm. All image browsing, multiplanar reformation (MPR) and data measurement were performed using RadiAnt DICOM Viewer 5.5.1.

2.3. Imaging analyses

Image analysis was performed by two radiologists with more than 10 years of experience, and the final statistical results were determined by consensus. The following manifestations were the focus of the analysis: “vascular thickening sign”; “air bronchogram sign”; “crazy paving pattern”; Fibrous characteristics: ① “fishing net on trees sign”: CT showed that the large area of consolidation was reduced, the density was reduced, the edge had shrunk, and there were significantly more bands and incomplete absorption of fibrosis shadows. The area was similar to a fishing net hanging on a branch that was not fully spread under the background of the increased bronchovascular bundle; and ② “subpleural line sign”: a long fibrosis shadow lying below and parallel to the pleura.

3. Results

Initial CT features of early-stage patients with COVID-19 (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Initial CT manifestations of lung lesions of the 126 cases by the time of onset of symptoms.

| Items | Frequency (%)∗ |

|---|---|

| Lesion distribution | |

| Unilateral | 14 (11.1%) |

| Bilateral | 112 (88.9%) |

| Localized | 20 (15.9%) |

| Diffuse | 106 (84.1%) |

| Lesion number | |

| Single | 11 (8.7%) |

| Multiple | 117 (92.9%) |

| Lesion shape | |

| Nodular | 84 (66.7%) |

| Patchy | 98 (77.8%) |

| Spherical | 52 (41.3%) |

| Flaky | 44 (34.9%) |

| Strip | 13 (10.3%) |

| Lesion density | |

| Pure GGO | 95 (75.4%) |

| Mixed GGO and consolidation | 31 (24.6%) |

| Vascular thickening sign | 98 (77.8%) |

| Air bronchogram sign | 70 (55.6%) |

| Crazy paving pattern | 93 (73.8%) |

| Pleura parallel sign | 72 (57.1%) |

| Fishing net on trees sign | 0 (0.0%) |

| Subpleural line sign | 6 (4.8%) |

Frequency statistics refer to the number of cases in which imaging manifestations occur/total number of cases in statistics.

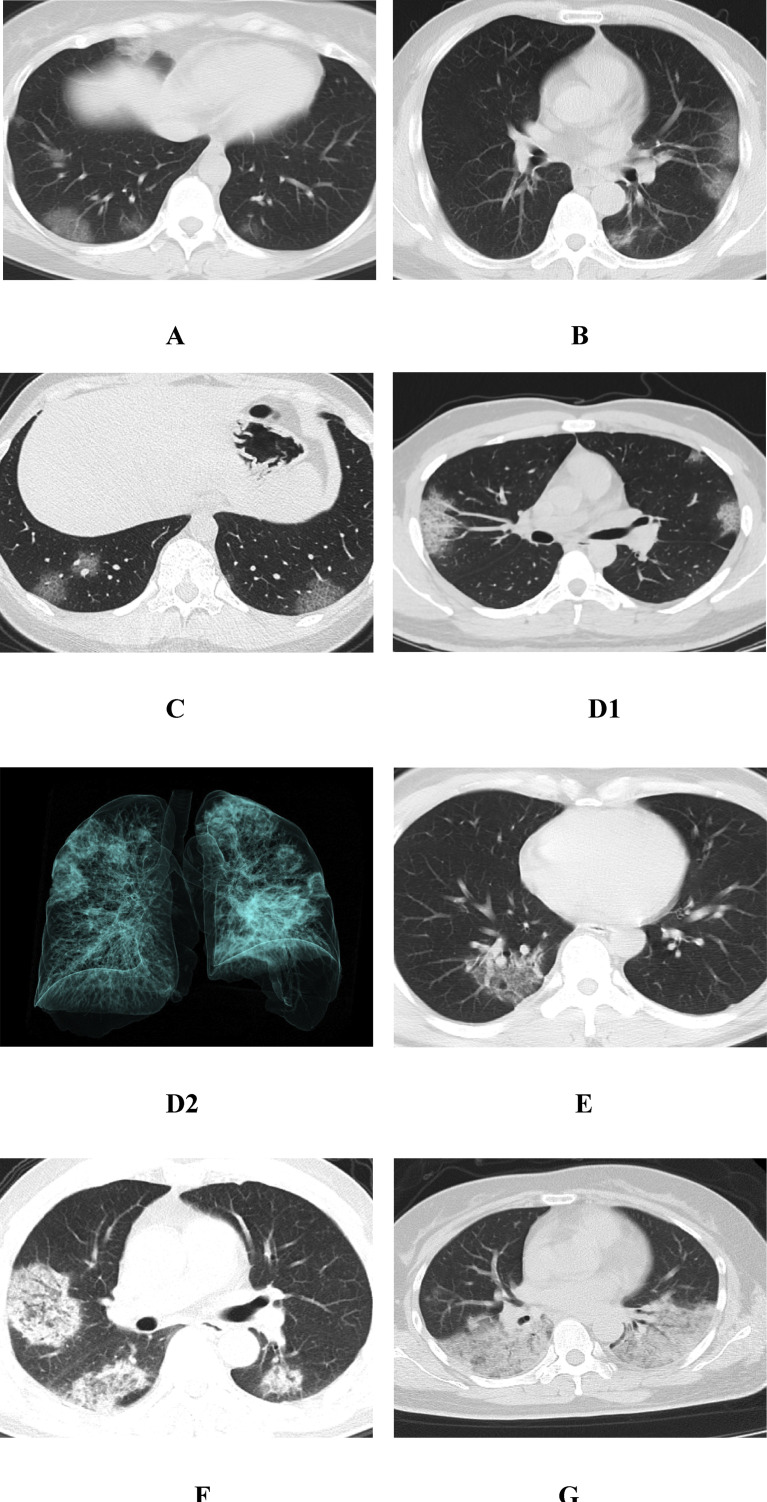

Lesion distribution: ① unilateral in 14 (11.1%) and bilateral in 112 (88.9%), localized in 20 (15.9%) and diffuse in 106 (84.1%); ② lesion number: single in 11 (8.7%) and multiple in 117 (92.9%); ③ lesion shape: nodular in 84 (66.7%), patchy in 98 (77.8%), spherical in 52 (41.3%), flaky in 44 (34.9%), and strip shape in 13 (10.3%); ④ lesion density: pure GGO in 95 (75.4%) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 A, B ) and mixed GGO and consolidation in 31 (24.6%) (Fig. 1, Fig. 4 A); and ⑤ the main accompanying CT features with a proportion of more than 50%: “vascular thickening sign” in 98 (77.8%) (Fig. 1 A, C), “air bronchogram sign” in 70 (55.6%) (Fig. 1 B−D), “crazy paving pattern” in 93 (73.8%) (Fig. 1 C, D1), and “pleura parallel sign” in 72 (57.1%) (Fig. 1 B).

Fig. 1.

The initial CT features of early-stage patients with COVID-19. A, a 26-year-old woman with pharyngeal pain for 3 days. CT showed that the lower lobes of the two lungs were mainly in the subpleural region, and there were multiple nodular GGOs around the bronchus. The boundary was clear, and there was a natural “vascular thickening sign”. B, a 36-year-old man with fever for 5 days. CT showed multiple GGOs in the subpleural region of the left lower lobe of the lung, showing a “pleura parallel sign” with a clear boundary and a natural “vascular thickening sign”. C, a 38-year-old man with fever for 6 days. CT showed that there were multiple nodular GGOs in the subpleural of the two lower lobes, with a “crazy paving pattern”. D1, a 20-year-old man with a cough for 7 days. CT showed multiple nodular and patchy GGOs in the subpleural region of the upper lobes of the two lungs, with a clear boundary. Inside, there was a clubbed “vascular thickening sign” and a clear “crazy paving pattern”. D2, The three-dimensional reconstruction of the lung volume in the same patient, which more intuitively shows the distribution characteristics of the focus, and some of the focus can be seen adjacent to the pleural depression. E, a 44-year-old woman with fever for 8 days. CT showed a flaky GGO in the lower lobe of right lung, with a clear boundary, with a clubbed “vascular thickening sign” and an “air bronchogram sign” in it. F, a 55-year-old man with fever for 10 days. CT showed that there were multiple patchy, flaky and globular GGOs with consolidation in the upper lobe of the right lung and the lower lobes of the two lungs under the pleura, with a clubbed “vascular thickening sign” and an “air bronchogram sign”. G, a 60-year-old woman with a cough, expectoration and fever for 11 days. CT showed large consolidation in the lower lobes of both lungs, with an “air bronchogram sign”.

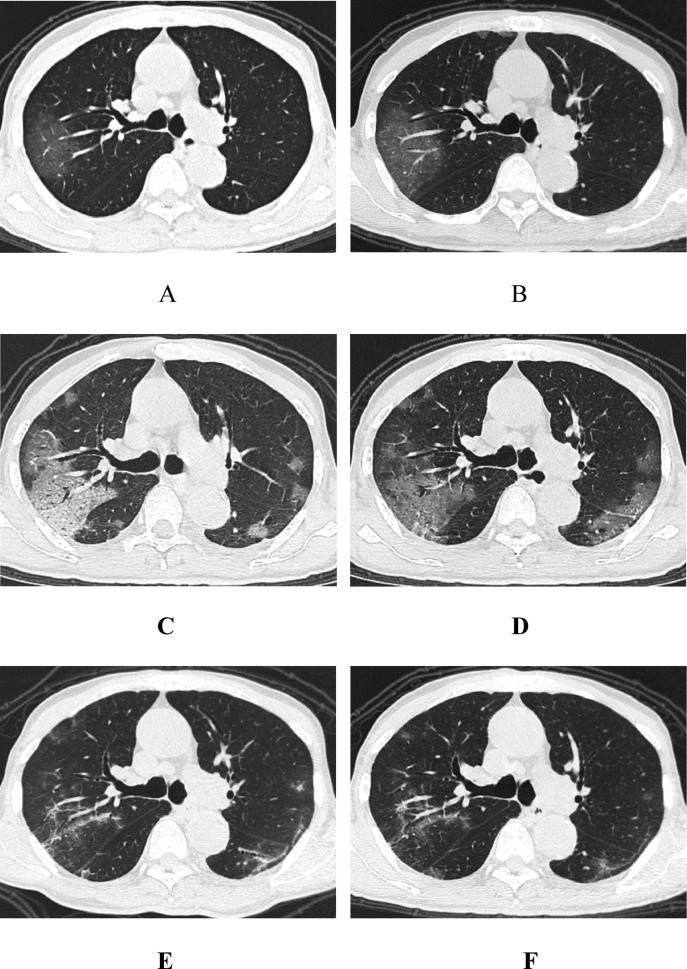

Fig. 2.

A, An 82-year-old man with fever for 3 days before admission. The first non-contrast-enhanced chest CT showed patchy GGOs in the subpleural area of the right upper lobe of the lung; the boundary was still clear, and there was a natural “vascular thickening sign”. B, 1 day after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed enlarged lesions as well as a natural “air bronchogram sign”. C, 6 days after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed enlarged lesions and increased consolidation, as well as a “crazy paving pattern”, a clubbed “vascular thickening sign” and “bronchiectasis sign”, indicating disease progression. Multiple nodular GGOs were also seen under the pleura of the other lung lobes. D, 12 days after treatment, the follow-up CT showed that the consolidation of the upper right lung lobes had weakened, with the left lung lesions having lamellar fusion and showing a “pleura parallel sign”. E, 16 days after treatment, the follow-up CT showed that the right upper lobe of the lung was further absorbed with a “fishing net on trees sign”, and the left lung lesions were absorbed with a “subpleural line sign”. F, 19 days after treatment (before discharge), the follow-up CT showed that the two lung lesions were further absorbed and thinned, with a small “grid shadow” and “fibrosis sign” remaining. No new lesions were found, and other accompanying signs had decreased.

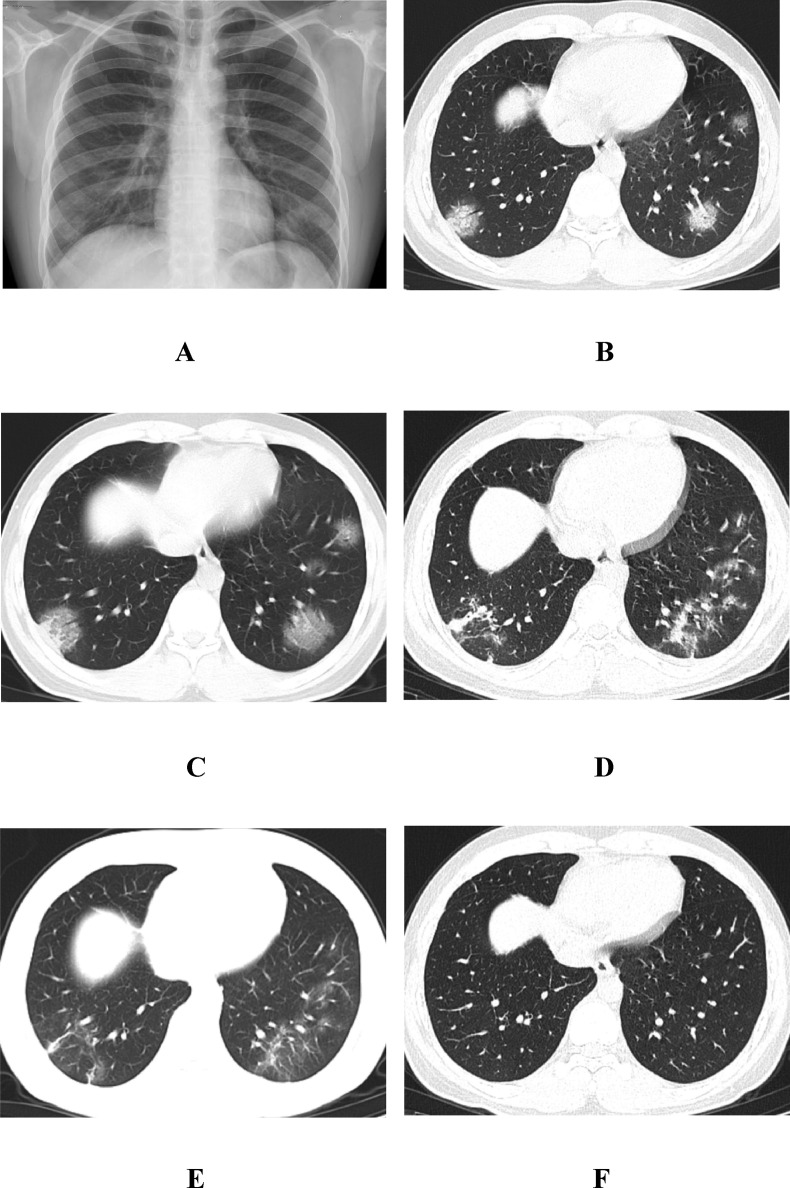

Fig. 3.

A, a 23-year-old man with fever for 6 days before admission. The first chest radiograph showed multiple GGOs in the two lungs, mainly distributed in the subpleural area. B, the first chest CT showed multiple GGOs in the lower lobe of the two lungs, mainly in the subpleural region and around the branch gas tube bundle, with a clubbed “vascular thickening sign”, a “crazy paving pattern” and an “air bronchogram sign”. C, 1 day after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed increased GGOs in the two lower lungs. Among them, the local consolidation of the lesions in the right lower lobe of the lung were seen to increase. D, 11 days after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed that the two lung lesions had lamellar fusion and had become obviously thin. E, 18 days after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed that the two lung lesions were further absorbed and became thin, the scope became small, and a small fiber strip shadow could be seen. F, 20 days after treatment (before discharge), the follow-up CT scan showed that the two lung lesions were completely absorbed and had disappeared.

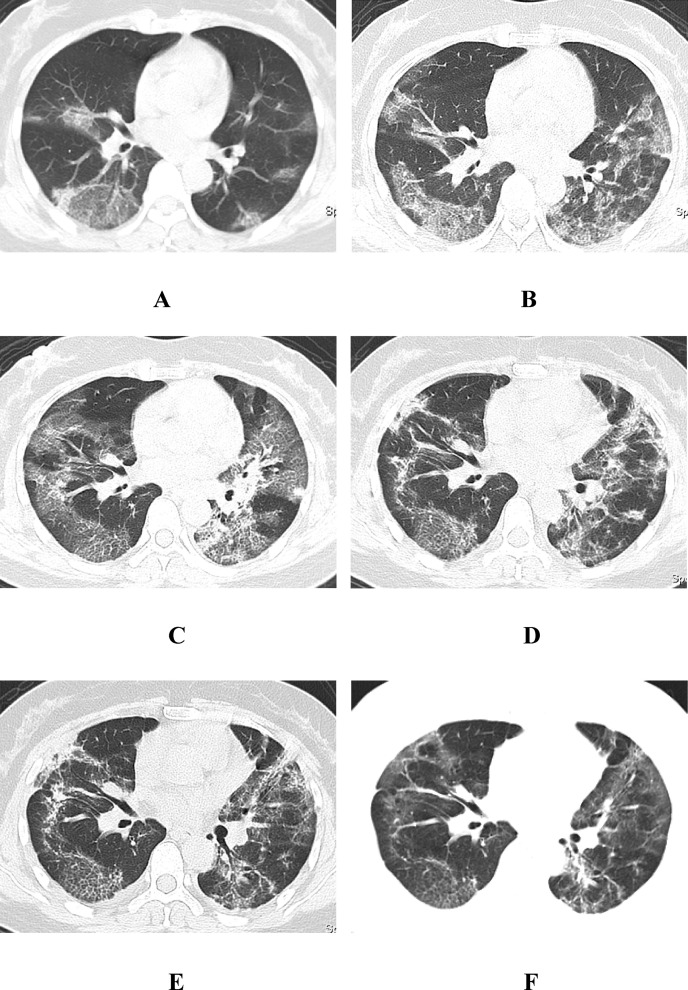

Fig. 4.

A, a 47-year-old woman with fever and chest distress for 9 days before admission. The first chest CT showed multiple patchy and flaky GGOs in the subpleural region of both lungs, with a clear boundary, as well as a natural “vascular thickening sign”, a clubbed “vascular thickening sign”, a fuzzy “crazy paving pattern” and an “air bronchogram sign”. B, 3 days after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed that the two lung lesions were enlarged and that some of the fusion was irregular, with a clear “crazy paving pattern”. C, 6 days after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed further expansion of the two lung lesions, including focal consolidation with GGOs in the left lung. D,E, 13 and 18 days after treatment, the follow-up CT scan showed that the two lung lesions had been gradually absorbed and faded, and more grid shadows and fibrous cord shadows appeared, showing the change in the “fishing net on trees sign”. F, 31 days after treatment (before discharge), the follow-up CT scan showed that the remaining grid shadows and fibrous cord shadows of the original two lungs were further absorbed and faded, with only a few signs of a light “grid shadow”, a “fibrosis sign” and remaining GGOs, and other accompanying signs had basically disappeared.

3.1. Dynamic evolution characteristics from the stage of admission to discharge

-

3.1.1

Imaging findings of the progression process: the main CT changes were increased GGOs with consolidation (118/126, 93.7%), an increased “crazy paving pattern” (104/126, 82.5%) (Fig. 4 B), an increased “vascular thickening sign” (105/126, 83.3%), and an increased “air bronchogram sign” (95/126, 75.4%) (Fig. 2, Fig. 4 C) (Table 3 ).

-

3.1.2

Imaging findings of the absorption process: the main CT changes were the obvious absorption of consolidation displayed as inhomogeneous partial GGOs with fibrosis shadows (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 D, E), the occurrence of a “fishing net on trees sign” (45/126, 35.7%), an increased “fibrosis sign” (40/126, 31.7%), an increased “subpleural line sign” (35/126, 27.8%), a decreased “crazy paving pattern” (19.8%), and a decreased “vascular thickening sign” (23.8%) (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4C) (Table 3).

-

3.1.3

In the stage of discharge, the main CT manifestations were further absorption of GGOs, consolidation and fibrosis shadows in the lung, and no appearance of new lesions (Fig. 3 F), with only a small amount of shadow with fibrotic streaks and reticulations remaining in some cases (16/126, 12.7%) (Fig. 2, Fig. 4F).

Table 3.

The main dynamic evolution characteristics of lung lesions on CT during hospitalization.

| Items | Imaging findings of progression process | Imaging findings of absorption process |

|---|---|---|

| GGOs with consolidation | 118 (93.7%)↑ | 32 (25.4%)↓ |

| Vascular thickening sign | 105 (83.3%)↑ | 30 (23.8%)↓ |

| Air bronchogram sign | 95 (75.4%)↑ | 22 (17.5%)↓ |

| Crazy paving pattern | 104 (82.5%)↑ | 25 (19.8%)↓ |

| Fishing net on trees sign | 6 (4.8%)↑ | 45 (35.7%)↑ |

| Subpleural line sign | 19 (15.1%)↑ | 35 (27.8%)↑ |

GGOs, ground-glass opacities.

4. Discussion

The dynamic evolution of the CT features of COVID-19 is closely related to the pathological changes of the disease [6]. This study attempts to analyze the initial CT features of 126 COVID-19 patients in the early stage and dynamic evolution characteristics of the progression and absorption process from the stage of admission to discharge, in order to provide imaging warnings for the improvement and deterioration of the clinical monitoring of diseases.

4.1. Initial CT features and pathological basis of COVID-19

The main general manifestations were multiple lungs with pGGOs chiefly distributed under the pleura, which was the characteristic CT manifestation of COVID-19, consistent with previous reports [[7], [8], [9]]. The feature of multiple lung lobes involved may be related to the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 and the way it spreads randomly within the respiratory tract [10]. The main feature of the subpleural distribution may be related to the small size of the lesion and the ease with which it reaches the farthest end of the respiratory tract. According to the published severe COVID-19 autopsy and pathology report [[11], [12], [13]], the cause of the early formation of GGOs may be related to the exudation of inflammatory cells and fibroblast-like cells in the lung interstitium, as well as the exudation of a small amount of fluid in the alveoli and edema of the alveolar wall.

The main accompanying CT features were as follows: ① “Crazy paving pattern”: this sign is formed by the thickening of the leaflet interval within the lesion superimposed on the GGO background, and the pathology represents the inflammatory edema of the leaflet interval [14]. ② “Vascular thickening sign”: in most cases the thickened blood vessels in the lesion were more naturally shaped, from thick to thin, with smooth edges, which may be related to edema of the blood vessel wall caused by inflammatory stimulation of the pulmonary artery branch [15]. In addition, “clubbed” thickened blood vessels were observed with GGOs in some cases in this group, with stiff travel and poorly smooth contours, which may be related to the severity of inflammation and the traction of local fibrosis. ③ “Air bronchogram sign”: this sign may represents the normal display of the bronchus in the lesion against the background of GGO [16], and the bronchiectasis sign which may be related to distal airway occlusion and local fibrosis traction, so the lumen was dilated, the wall was thickened, and the shape was stiff, which may be related to the severity of disease. ④ “Pleura parallel sign”: this sign must meet the two conditions that the lesion has a subpleural distribution and that the largest diameter is parallel to the pleura [17]. Its possible formation mechanism is that the diffusion of the subpleural lesion to the pleural side is limited; therefore, it can only spread to both sides along the reticular structure of the interlobular septal edge by sticking to the pleura, and the fusion of subpleural lesions results in the long axis of the lesion being parallel to the pleura. It is the more characteristic CT sign of COVID-19, which is also called the “bat wing sign” or “anti-pulmonary edema sign” in some studies [18].

4.2. Dynamic evolution characteristics from the stage of admission to discharge

According to the analysis of this group of patients, the majority of COVID-19 cases may be effectively relieved following standardized treatment after admission, but it will still be further aggravated to the peak of the disease, therefore, the course of COVID-19 could be divided into two parts: progression process and absorption process.

4.2.1. Imaging findings of the progression process

In this group of data, 93.7% of cases progressed after admission, mainly manifested by the expansion of the original lesion and varying degrees of consolidation. The occurrence of consolidation may be associated with increased fibrous mucus-like exudate, cell shedding, hyaline membrane formation and hemorrhagic pulmonary infarction, and some consolidation may also be combined with bacterial infections [[11], [12], [13]]. With the progression of the disease, the proportions of accompanying signs such as the “crazy paving pattern”, “vascular thickening sign” and “bronchiectasis sign” all increased, which may be related to the severity of inflammation and the traction of local fibrosis.

4.2.2. Imaging findings of the absorption process

After COVID-19 reached the peak of the disease course, the lesions began to be gradually absorbed, and they returned to the recovery stage [19]. This group of cases showed that absorption was not synchronous, which may be related to the inconsistency of the time and degree of the occurrence and development of the lesion, so the CT characteristics of density and morphology were varied. Along with the absorption of consolidation, more fiber and grid shadows appeared, and the appearance of the “fishing net on trees sign” was demonstrated against the thickened bronchovascular bundles. The pathological basis may be the combination of cellulose-like exudation in the pulmonary interlobular septum with thickened and centripetally constricted bronchovascular bundles. This sign, which was first proposed by the author, has certain characteristics and is representative, indicating that the pulmonary lesions are in the stage of obvious absorption but not complete absorption, which should be given more attention to prevent the reversal of the disease. In this group, the “subpleural line sign” and “fibrosis sign” increased. The former represents the absorption outcome of a type of lesion with a “pleura parallel sign”, while the latter is a common imaging sign in the recovery period of inflammation and is also common in other types of pulmonary infections. In this study, whether the appearance of the fibrosis shadow represents the reversal of the disease or the early manifestation of terminal pulmonary fibrosis needs further follow-up observation [20]. In addition, with the remission of the disease, the proportions of concomitant signs such as “crazy paving pattern”, “vascular thickening sign”, and “bronchiectasis sign” mentioned above, which represent disease progression, decreased or even disappeared.

4.2.3. CT features in the stage of discharge

In this group, all patients were ultimately discharged after being cured. In the last CT examination before discharge, fibrosis structures such as the “fishing net on trees sign” and “subpleural line sign” that appeared in the improvement of most cases were completely absorbed (approximately 68%), with only a small amount of fibrosis and grid shadows remaining in some cases (12.7%). The author believes therefore, that the fibrosis characteristics of the lungs during the recovery stage of COVID-19 pneumonia represent the absorption of disease reversal, which can be fully absorbed with the extension of review time, rather than the early manifestations of end-stage pulmonary fibrosis [21]. The so-called “fibrosis shadow” is likely to be a temporary image manifestation caused by residual cellulose-like exudation or incomplete absorption of consolidation.

In summary, the initial CT features of early-stage patients with COVID-19 often showed multiple patchy and nodular GGOs mainly distributed in the peripheral lungs, with “crazy paving pattern”, “vascular thickening sign” and “air bronchogram sign” being the main accompanying CT features. The dynamic evolution characteristics have certain regularity, which often showed a progression process and an absorption process, among which the absorbed fibrosis shadow was the main CT feature of COVID-19 in the stage of discharge. CT of the chest is critical for early detection, evaluation of disease severity and follow-up of patients.

Ethic statement

This consensus was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China and all the subjects offered their written informed consent form.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Qing Zang, Rentao Liang, Peiqi Ma, Lingling Wang for providing the cases and Xiaomin Zheng, Cuiping Li, Xin Wang for providing language help.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing You'an Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University.

References

- 1.Song F., Shi N., Shan F., Zhang Z., Shen J., Lu H. Emerging 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295:210–217. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang D., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sverzellati N., Milone F., Balbi M. How imaging should properly be used in COVID-19 outbreak: an Italian experience. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26:204–206. doi: 10.5152/dir.2020.30320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee E.Y.P., Ng M.Y., Khong P.L. COVID-19 pneumonia: what has CT taught us? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:384–385. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan Y., Guan H., Zhou S., Wang Y., Li Q., Zhu T. Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:3306–3309. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06731-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang W., Cao Q., Qin L., Wang X., Cheng Z., Pan A. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):A multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020;80:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han R., Huang L., Jiang H., Dong J., Peng H., Zhang D. Early clinical and CT manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei J., Xu H., Xiong J., Shen Q., Fan B., Ye C. 2019 Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia: serial computed tomography findings. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:501. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lal A., Mishra A.K., Sahu K.K. CT chest findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:1000–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y., Liu Q., Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:418–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian S., Hu W., Niu L., Liu H., Xu H., Xiao S.Y. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y., Zhou W., Yang L., You R. Physiological and pathological regulation of ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 receptor. Pharmacol Res. 2020;157:104833. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao D.M., Zhou N., Zheng D., Yue J.C., Zhao Q.H., Luo B. Guide to the forensic pathology practice on death cases related to corona virus disease 2019 COVID-19 trial draft. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;36:5–6. doi: 10.12116/j.issn.1004-5619.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salehi S., Abedi A., Balakrishnan S., Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qanadli S.D., Beigelman-Aubry C., Rotzinger D.C. Vascular changes detected with thoracic CT in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) might Be significant determinants for accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:W1. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei J., Li J., Li X., Qi X. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295:18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X., Zeng W., Li X., Chen H., Shi L., Li X. CT imaging changes of corona virus disease 2019(COVID-19): a multi-center study in Southwest China. J Transl Med. 2020;18:154. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02324-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu X., Yu C., Qu J., Zhang L., Jiang S., Huang D. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2020;47:1275–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04735-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Z., Shi J., He Z., Lü Y., Xu Q., Ye C. Predictors for imaging progression on chest CT from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Aging. 2020;12:6037. doi: 10.18632/aging.102999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joob B., Wiwanitkit V. Computed tomographic findings in COVID-19. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21:620. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Huang M., Zeng X. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295:202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]