To the Editor,

We appreciated the commentary by Garattini and colleagues [1] on the lessons that the Italian National Health Service (INHS) should learn from COVID-19. Building on their correct assessment of the situation, we would like to offer some additional suggestions for discussion, stressing two concepts: balance between technical and political governance, and INHS funding.

Garattini et al. [1] state that COVID-19 has tested the fabric of the INHS and wish for a more profound reorganization of the Italian regions to pave the way to rational planning and coherent national and regional strategy. As we previously discussed in this Journal [2], the INHS is indeed a ‘galaxy’ of regional healthcare services, a complex macro-cosmos of different healthcare systems. We agree with the authors about the difficulties in managing and providing the same quality of care with such a heterogenous healthcare system. We also concur with them and additionally stress that an in-depth scrutiny of the balance between technical and political governance among regional healthcare systems is needed. This balance is an inherited bias of the INHS, where politics has for too long influenced healthcare policies. We do not argue against the importance of a public and universalistic system, the importance of which has been highlighted by the pandemic [3]. Nevertheless, COVID-19 also displayed some critical issues in the organization of the INHS, where each regional government is responsible for providing ‘essential levels of care’ to the population through autonomous planning and delivery of healthcare services. For instance, in Lombardy, the first and most affected region of Italy and Europe, the healthcare system is publicly funded but services are provided by private institutions more than in other regions (i.e. the public/private share of health institutions is unbalanced towards the latter). In recent years, Lombardy’s regional policy makers have fostered a highly hospital-centric organization, composed of world-renowned hospital expertise, at the expense of primary care, intermediate care and general medicine, which for several years have been reformed and down-regulated. This determined a decrease in the capacity of hospital-territory integration and coordination. Moreover, the inadequacy and low preparedness of the primary-care services seem to have contributed to the uncontrolled spreading of the virus, leaving hospitalization as the first option when people showed symptoms.

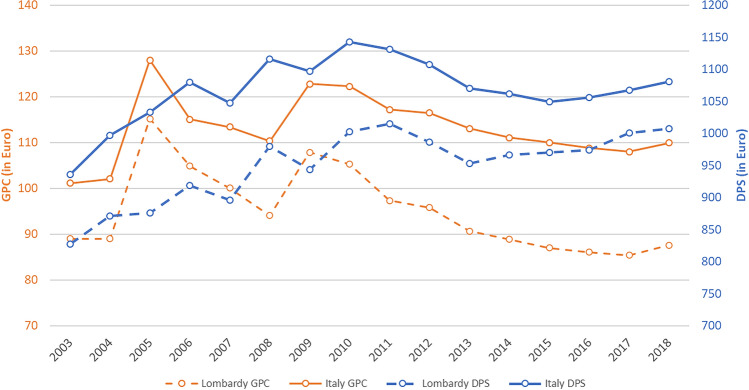

The performance level of a national health service largely also depends on its funding. Despite the fact that Italy’s total health expenditure accounts for around 8.8% of its GDP, in line with the average of OECD contruries, the INHS has been subjected to continuous spending constraints in the past two decades. After several years of little increase or even decreased health spending, following the 2008 economic crisis, growth rates picked up again only recently [4]. However, how is this money spent? The greatest share of healthcare expenditure—typically acconting for around 60% of all health spending across OECD countries—comprises inpatient and outpatient services [5]. Within such services, as mentioned by Garattini and colleagues [1], accident and emergency services (AEs) are the ‘pillar’ of emergency care in the INHS. According to the definition and categorization of the OECD’s manual A System of Health Accounts [6], the spending item that encompasses the majority of inpatient and outpatient services (including AEs) in Italy is DPS (directly provided services). This expenditure item includes spending for all individual health-related goods and services directly provided by the Italian NHS, i.e. by AEs, general and specialized hospital wards, and so on. In our previous work [2], we identified DPS as the major driving force of the INHS, the one most closely related to overall mortality rate, one of the most important outcome measures for evaluating a health system’s performance. However, this spending item adjusted by inflation saw a constant reduction in recent years together with an even stronger reduction in the spending for primary care (Fig. 1). This may have impacted the system’s response to COVID-19. Moreover, the much needed generational turnover is not happening at an adequate rate in Italy, leaving the country with the highest prevalence in Europe of physicians aged > 55 years [7]. This contributes to the low resilience of the INHS, as also pointed out by Garattini and colleagues [1].

Fig. 1.

Inflation-adjusted per capita health spending for directly provided services (DPS) and general practitioner and primary care (GPC) in Italy and the Lombardy region (years 2003–2018). DPS: Spending for social transfers in kind representing all the individual health-related goods and services provided free of charge directly by the INHS (i.e. hospital wards and offices, AEs, etc.). GPC: spending for primary care and general practitioners, outpatient paediatrics and public doctor on-call services. Since 2010 the difference between GPC spending at the national and regional level has been increasing when compared to DPS, highlighting a shift of resources away from primary care. The relative change in DPS between Italy and Lombardy is on average 13% from 2003 to 2010 and 9% from 2011 to 2018. The relative change in GPC between Italy and Lombardy is on average 12% from 2003 to 2010 and 20% from 2011 to 2018. Data used here are publicly available by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/14562)

We also want to express our concern regarding one of the vital services in the fight against pandemics: departments of public health (DPHs). With their skill-mix composed of epidemiologists, nurses and prevention technicians, they represent the ‘brain’ in the prevention of communicable and non-communicable diseases. However, Italian DPHs have also been underfunded and overlooked in the last decades. In fact, while hospital and territorial health expenditure account respectively for 50% and 45%, only 5% is allocated to surveillance and prevention activities [8].

COVID-19 has challenged health systems globally. The Italian system was under enormous stress, given the severity of the outbreak, and relied on the heroic sacrifices of many. It is plausible that an emerging infectious disease is not the worst-case scenario that our health systems could face. Other global events, such as climate change, could hit both acutely, with heat waves, floods, drought, or emerging pathogens, potentially even more dangerous than SARS-CoV-2, and in a more nuanced way, through pollution and the accumulation of noxae that can lead to the onset of tumors and other chronic diseases. Lessons to be learned from this annus horribilis 2020 is that it is necessary that health systems are well equipped with economic, human and technological resources to be resilient in the face of unpredictable events.

In the light of the presented facts and wishing to corroborate the authors’ stance, we strongly believe that a comprehensive analysis of the technical/political balance of the INHS, together with a review of its funding, is mandatory. We strongly argue that one of the first steps to strengthen the Italian system is to stop underfunding it, and to enhance sectors that have for too long been neglected, like primary care and public health.

Author Contributions

DG, AB, KYCA and FT conceived and shared the idea of this letter to the editor and equally contributed to its content.

Availability of Data and Material

Data are made publicly available by the Italian National Institute of Statistics in the ‘Health for all’ database, available from https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/14562.

Declarations

Funding

None declared.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Davide Golinelli, Email: davide.golinelli@unibo.it.

Andrea Bucci, Email: andrea.bucci@unich.it.

Kadjo Yves Cedric Adja, Email: adjayvescedric@gmail.com.

Fabrizio Toscano, Email: fatoscano@montefiore.org.

References

- 1.Garattini L, Zanetti, Freemantle N. The Italian NHS: what lessons to draw from COVID-19? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020. 10.1007/s40258-020-00594-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Golinelli D, Toscano F, Bucci A, Lenzi J, Fantini MP, Nante N, Messina G. Health expenditure and all-cause mortality in the ‘galaxy’ of Italian regional healthcare systems: a 15-year panel data analysis. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(6):773–783. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0342-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takian A, Aarabi M, Haghighi H. The role of universal health coverage in overcoming the covid-19 pandemic. In: BMJ Opinion. 2020. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/04/20/the-role-of-universal-health-coverage-in-overcoming-the-covid-19-pandemic/ Accessed 13 July 2020.

- 4.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2018: 10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-en Accessed 13 July 2020.

- 5.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. 10.1787/4dd50c09-en Accessed 13 July 2020.

- 6.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. A system of health accounts. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/a-systemof-health-accounts_9789264116016-en Accessed 13 July 2020.

- 7.Toscano F, Golinelli D. Italian National Health Service: defusing the bomb. Public Health. 2017;153:176–177. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.4th GIMBE report on the sustainability of the Italian National Health Service. GIMBE Foundation. 2019. Bologna, Italy. www.rapportogimbe.it. Accessed 13 July 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are made publicly available by the Italian National Institute of Statistics in the ‘Health for all’ database, available from https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/14562.