Significance

A variety of neurodegenerative diseases show selective neuronal loss in distinct brain regions. It remains unclear how the ubiquitously expressed disease proteins can cause selective neurodegeneration. In Huntington’s disease, neuronal loss preferentially occurs in the striatum. Using Huntington’s disease mice, we found that loss of Hap1 selectively causes neuronal degeneration in the striatum. We further identified that this selective neuronal degeneration also depends on mutant HTT and Rhes, a striatal enriched protein. Hap1 deficiency causes more Rhes to bind mutant HTT to yield a toxic form of mutant HTT. Our findings suggest that multiple factors are involved in the selective neuronal loss in neurodegenerative diseases and that their specific interaction can serve as a therapeutic target.

Keywords: huntingtin-associated protein, aggregates, polyglutamine, neurodegeneration, sumoylation

Abstract

Huntington disease (HD) is an ideal model for investigating selective neurodegeneration, as expanded polyQ repeats in the ubiquitously expressed huntingtin (HTT) cause the preferential neurodegeneration in the striatum of the HD patient brains. Here we report that adeno-associated virus (AAV) transduction-mediated depletion of Hap1, the first identified huntingtin-associated protein, in adult HD knock-in (KI) mouse brains leads to selective neuronal loss in the striatum. Further, Hap1 depletion-mediated neuronal loss via AAV transduction requires the presence of mutant HTT. Rhes, a GTPase that is enriched in the striatum and sumoylates mutant HTT to mediate neurotoxicity, binds more N-terminal HTT when Hap1 is deficient. Consistently, more soluble and sumoylated N-terminal HTT is presented in HD KI mouse striatum when HAP1 is absent. Our findings suggest that both Rhes and Hap1 as well as cellular stress contribute to the preferential neurodegeneration in HD, highlighting the involvement of multiple factors in selective neurodegeneration.

Selective neuronal loss in distinct brain regions in a variety of neurodegenerative diseases has been a challenging issue to address. This is because the disease proteins have multiple functions and are expressed ubiquitously in different types of cells. Understanding the mechanism underlying the selective neuronal loss is highly important for developing effective treatment, as therapeutic approaches can be focused on the specific targets to reduce adverse effects on the normal function of the disease proteins.

Huntington’s disease (HD) appears to be an ideal model for investigating selective neurodegeneration. First, HD is caused by a monogenic mutation or polyCAG/glutamine expansion in the HD gene (1, 2), which enables the generation of animal models that can precisely mimic the genetic defect in humans. Second, the HD protein, huntingtin (HTT), possesses multiple functions but causes selective neuronal vulnerability despite its ubiquitous expression (3). Third, the neuropathology of HD is featured by the preferential neuronal degeneration in the striatum (4, 5). The selective neuronal loss in HD has promoted extensive studies of HTT interacting proteins that may be involved in HD neuropathology. Hap1, huntingtin-associated protein 1, was the first identified protein that binds mutant HTT more tightly (6). Further studies demonstrated that Hap1 and HTT are associated with trafficking proteins to participate in intracellular transport and that mutant HTT can affect this important function (7–12). However, Hap1’s expression is not restricted to the striatum, although it is enriched in neuronal cells (13–15). Instead, the relative low level of Hap1 in the striatum was thought to contribute to the striatal neuronal vulnerability (14, 15).

A promising candidate for the selective neuronal loss in the striatum in HD is Rhes, a small GTPase that functions as an E3 ligase for attachment of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) and is abundantly expressed in the striatum (16–18). Moreover, Rhes binds to and sumoylates N-terminal mutant HTT to decrease the formation of HTT aggregates and to promote cell death (19). As sumoylated HTT is more toxic (20), Rhes was thought to be involved in the striatal degeneration in HD (21, 22). However, altering Rhes expression in HD mouse models has led to conflicting results regarding the role of Rhes in HD phenotypes (23–27). It remains to be understood how Rhes is involved in the preferential neuronal loss in HD.

In the current study, we found that both Hap1 and Rhes participate in the selective neuronal degeneration in HD. Depletion of Hap1 in adult HD knock-in (KI) mouse brains via adeno-associated virus (AAV) transduction of CRISPR/Cas9 caused neuronal loss only in the striatum but not in other brain regions. Moreover, this degeneration requires the presence of mutant HTT. We also found that Hap1 deficiency caused more Rhes to bind mutant HTT and increased the level of sumoylated mutant HTT. We propose that the association of Hap1 with mutant HTT prevents Rhes’ binding and sumoylating mutant HTT to protect mutant HTT toxicity, whereas loss of Hap1 promotes mutant HTT toxicity in the striatum.

Results

Depletion of Hap1 in Adult Mouse Brain.

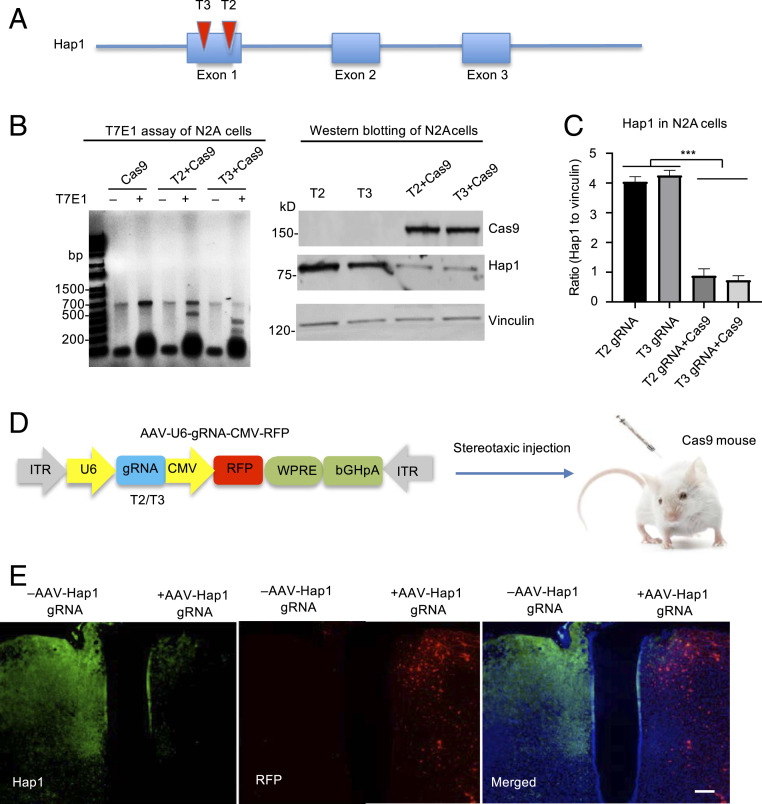

Hap1 has been found to be protective against neuronal degeneration (28–31). Consistently, Hap1’s expression is more abundant in the neurons spared from degeneration in HD (29, 32, 33), and its low level in the striatum correlates with the great vulnerability of striatal neurons in HD (14, 15). These interesting findings inspired us to investigate whether Hap1 is involved in the preferential neuronal degeneration in HD. To this end, we designed two guide RNAs (gRNAs) (T2 and T3) to target exon1 of the mouse Hap1 gene for investigating the effect of Hap1 deficiency (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). We first tested targeting efficiency of Hap1 gRNAs by transfecting them with Cas9 in cultured mouse neuroblastoma cells (N2a) and in the mouse brain. DNA analysis with T7E1 digestion revealed that both Hap1 gRNAs could efficiently disrupt the Hap1 gene and generate mutations in the targeted region (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C). Western blotting also showed that Hap1 expression was markedly reduced by Hap1 gRNAs (Fig. 1C). We then combined equal amounts of AAV-Hap1 gRNAs (T2 and T3) for depleting the Hap1 gene in the mouse brain.

Fig. 1.

Efficient knocking down Hap1 via CRISPR/Cas9. (A) Two Hap1 gRNAs (T2 and T3) were designed to target exon1 of the mouse Hap1 gene. (B) T7E1 assays and Western blotting verified that CRISPR/Cas9 targeting could cause mutations in the Hap1 gene (Left) and markedly reduce the expression of Hap1 in transfected N2a cells (Right). (C) Densitometric ratios of Hap1 to vinculin on Western blots in B. The data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3), ***P < 0.001. (D) Hap1 gRNAs are expressed by AAV vector that also expresses RFP under the control of the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The packaged AAV9 viruses were stereotaxically injected into the brain of Cas9-transgenic mice. (E) Double-immunofluorescent staining showing that expression of AAV-Hap1 gRNA and RFP (red) led to a marked reduction of Hap1 (green). The merged image also shows nuclear staining (blue). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

To examine the targeting effect in vivo, we used Cas9 mice that express Cas9 ubiquitously under the pCAG promoter after Cre-recombination (34). We also crossed Cas9 mice with HD140Q KI mice and confirmed the expression of Cas9 and mutant HTT in the crossed mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We first used Cas9 mice without expression of mutant HTT to perform stereotaxic injection of AAV viruses expressing Hap1 gRNA into the specific brain region (Fig. 1D). The AAV-Hap1 gRNA vector expressed Hap1 gRNA under the U6 promoter and also RFP under the CMV promoter. Thus, RFP expression in the injected brain region reflects the expression of Hap1 gRNA. We injected AAV-HAP1 gRNAs of T2 and T3 into one side of the hypothalamus of 4-mo-old wild-type (WT)/Cas9 mouse. The contralateral hypothalamus was injected with PBS as a control. After 21 d, immunofluorescent staining verified that RFP (red) was predominantly expressed and Hap1 immunostaining (green) was dramatically reduced in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA virus-injected hypothalamus (Fig. 1E), confirming that AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection could efficiently eliminate Hap1.

Deletion of Hap1 in Adult Mouse Brain Does Not Induce Neuronal Loss.

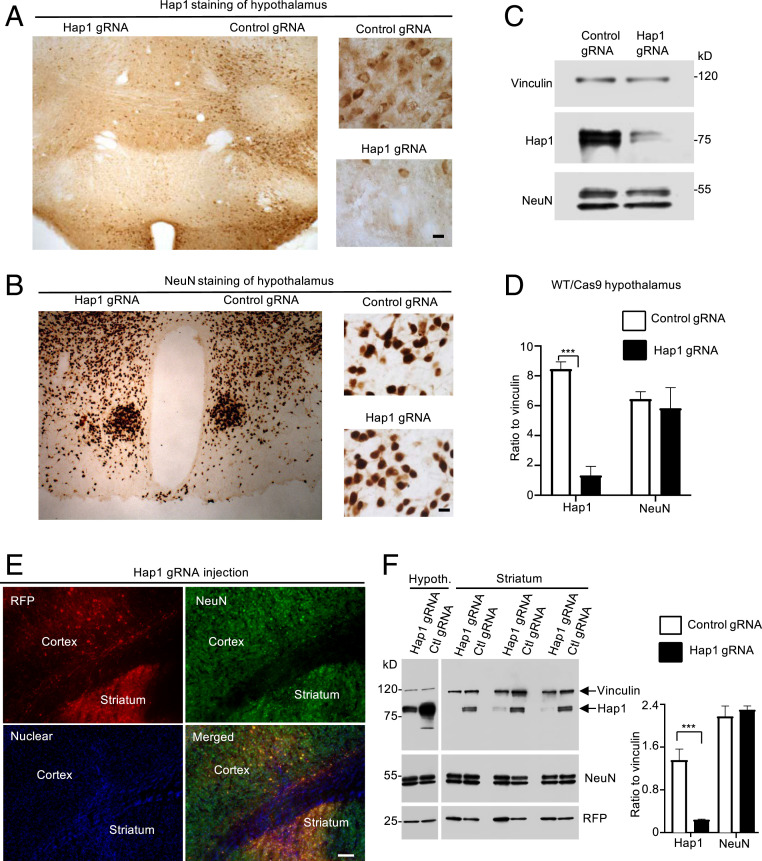

Next, we examined whether loss of Hap1 can induce neuronal loss in WT/Cas9 mice that express WT HTT. AAV-control gRNA that did not target to any known gene was also used for the injection in the contralateral side in the same animal in order to rule out the nonspecific effects caused by viral transduction. We first examined the hypothalamus, which expresses the highest level of Hap1 (13–15). Four weeks after the AAV injection into a 5-mo-old WT/Cas9 mouse, the injected mouse brain was examined. Although AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection could remarkably reduce Hap1 expression in the hypothalamus (Fig. 2A), there was no significant change in NeuN staining as compared with the AAV-control gRNA injection (Fig. 2B). Western blotting of another 6-mo-old WT/Cas9 mouse brain also showed that the significant reduction of Hap1 was not accompanied by altered change in NeuN (Fig. 2 C and D). We then examined the cortex and striatum that were injected with either AAV-Hap1 gRNA or AAV-control gRNA viruses. Similarly, Hap1 was significantly reduced by AAV-Hap1 gRNA, but no alteration in NeuN staining was seen between Hap1 gRNA- and control gRNA-injected groups (Fig. 2E). Western blotting of three mouse striatal tissues showed that AAV-Hap1 gRNA could significantly reduce Hap1 expression as compared with AAV-control gRNA injection (Fig. 2F). Like the hypothalamus in WT mouse, the striatum did not show any altered expression of NeuN when Hap1 was reduced (Fig. 2F). These findings are consistent with our early report that genetic depletion of the Hap1 gene in adult mouse brain did not induce neuronal loss (35).

Fig. 2.

Knocking down Hap1 in WT (WT/Cas9) adult mouse brain did not reduce neuronal numbers in various brain regions. (A and B) Immunostaining of AAV-Hap1 gRNA and AAV-control gRNA-injected mouse hypothalamus with anti-Hap1 (A) and anti-NeuN (B). (Right) The enlarged images. (C) Western blotting verified that CRISPR/Cas9 targeting reduced the expression of Hap1, but not NeuN, in the injected hypothalamus. (D) Densitometric ratios of Hap1 or NeuN to vinculin on Western blots in C. The data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3), ***P < 0.001. (E) Double-immunofluorescent staining of AVV-Hap1 gRNA-injected cortex and striatum showing NeuN (green) and RFP (red), which reflects AAV-Hap1 gRNA expression. Nuclear staining (blue) is also shown. (F) Western blotting analysis (Left) of Hap1, NeuN, RFP in the AAV-control gRNA or AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected hypothalamus and striatum. Densitometric ratios (Right) of Hap1 or NeuN to the loading control vinculin on Western blots (Left) are also presented. Ctl, control. The data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3), ***P < 0.001. (Scale bars, 10 μm [A and B]; 50 μm [E].)

Deletion of Hap1 via AAV Injection Caused Selective Neuronal Loss in the Striatum in HD KI Mice.

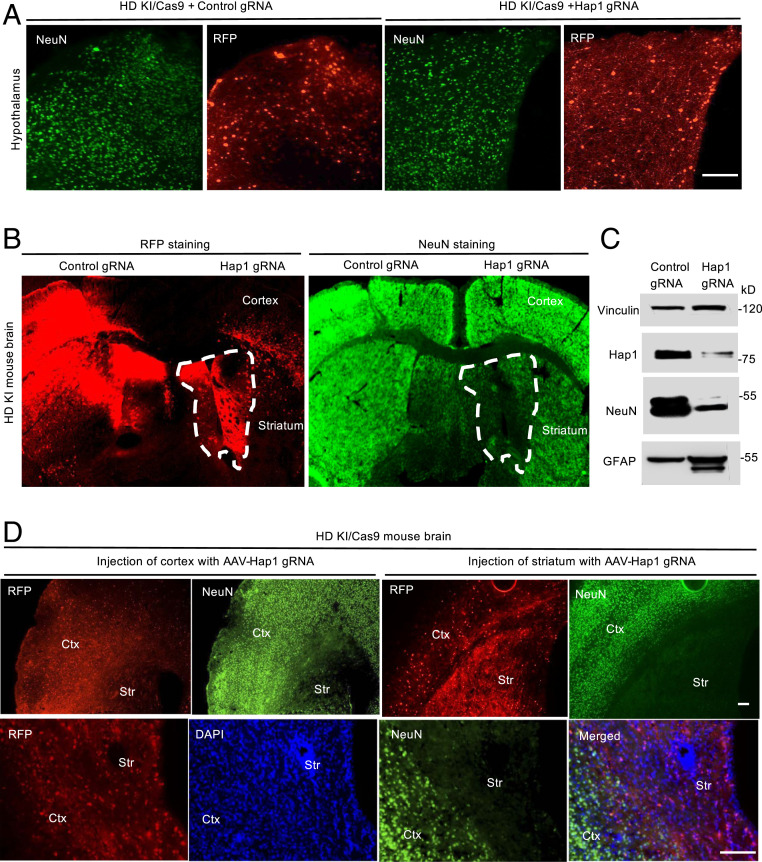

Since abnormal binding of mutant HTT to Hap1 can affect intracellular function (6, 8, 11, 36, 37), we wanted to examine the effect of loss of Hap1 in the striatum of HD KI mice when mutant HTT is present. In HD KI mice, the brain region to show the earliest nuclear accumulation and aggregation is the striatum, and the nuclear accumulation of mutant HTT occurs prior to its aggregation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (38–43). These unique pathological events allow for examining the effect of Hap1 depletion in the striatum. To do so, we used HD KI/Cas9 mice that express both mutant HTT and Cas9 at the endogenous level (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We injected three 5-mo-old KI/Cas9 mice with AAV-Hap1 gRNA and then examined them at 6 mo of age. We first focused on the hypothalamus, which expresses the highest level of Hap1. Depletion of Hap1 in the hypothalamus of KI/Cas9 mice did not yield any change in NeuN staining (Fig. 3A). However, when AAV-Hap1 gRNA was injected into the cortex and striatum of KI/Cas9 mice, only the striatum showed a dramatic reduction in NeuN staining (Fig. 3B). Western blotting results confirmed the drastic reduction of NeuN in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum as compared with the AAV-control gRNA-injected striatum (Fig. 3C). In a separate experiment using different HD KI/Cas9 mice that were also injected with AAV viruses at the age of 5 mo, we replicated the similar result that AAV-Hap1 gRNA selectively reduced NeuN staining in the striatum, but not in the cortex (Fig. 3D). The reduced number of NeuN-positive cells in the striatum was also confirmed by Nissl staining (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), and there was increased gliosis (reactive astrocytes and increased microglia) in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). These results further indicate that neurodegeneration in the striatum can be caused by loss of Hap1 when mutant HTT is present.

Fig. 3.

Hap1 depletion selectively reduced NeuN expression in the striatum in HD KI/Cas9 mice. (A) Immunostaining of HD KI/Cas9 mouse hypothalamus showing that AAV-control gRNA or AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection resulted in the same density of NeuN-positive cells. RFP represents the expression of AAV gRNA. (B) Immunostaining of HD KI/Cas9 mouse cortex and striatum showing that AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection selectively reduced the density of NeuN-positive cells in the injected striatum (indicated by dotted lines). (C) Western blotting verified the reduced Hap1 and NeuN levels in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum in HD KI/Cas9 mouse brain. (D) Additional immunofluorescent images of HD KI/Cas9 mice at 6 mo of age showing that expression of AAV-Hap1 gRNA (RFP) did not affect NeuN staining in the cortex (Ctx) but selectively diminished NeuN staining in the striatum (Str). The images (5X, Upper) show two brain sections that were stained by antibodies to NeuN and RFP. Enlarged images (Lower) show the staining of a different brain section in the same animal and a merged image with nuclear staining (DAPI). The images were obtained 1 mo after AAV-gRNA injection. (Scale bars, 50 μm [A and D].)

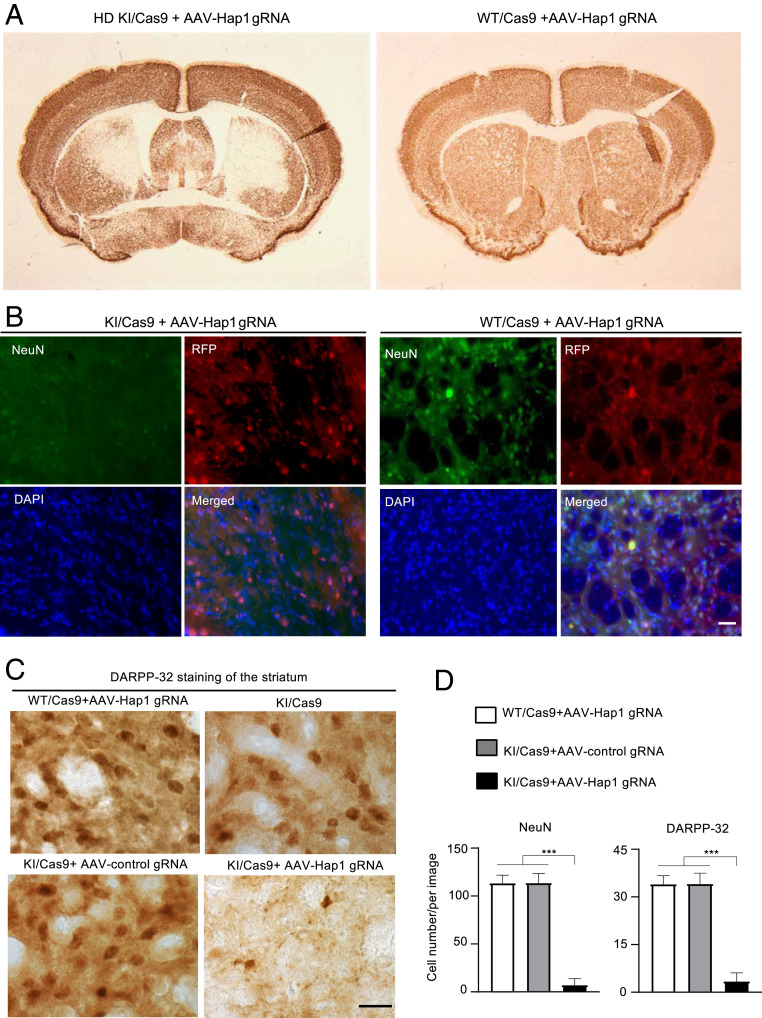

To provide more evidence to support this important finding, we performed bilateral injection of AAV-Hap1 gRNA into HD KI/Cas9 and WT/Cas9 mice at the same age (5 mo). Four weeks later, the injected brains were subjected to immunohistochemistry under the same staining conditions. The results again confirmed that AAV-Hap1 gRNA caused a marked reduction of NeuN staining in the HD KI striatum (Fig. 4A). Double-immunostaining also showed that in the injected HD KI striatum in which AAV-Hap1 gRNA was expressed, which was reflected by RFP, NeuN staining was hardly detected (Fig. 4B). Using an antibody to DARPP-32, a protein marker of striatal neurons, we also observed a significant reduction of DARPP-32–positive neurons in the HD KI striatum when Hap1 was depleted (Fig. 4 C and D).

Fig. 4.

Reduction of NeuN expression in the striatum by Hap1 depletion is dependent on the presence of mutant HTT. (A) Immunostaining of the brains of HD KI/Cas9 (KI/Cas9) and WT/Cas9 (Cas9) showing that AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection reduced NeuN staining only in the striatum of KI/Cas9 mouse brain. (B) Double-immunostaining of the striatum verified the transduction of AAV (red) and obviously reduced NeuN staining (green) in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum in a KI/Cas9 mouse as compared with a WT/Cas9 mouse. (C) Immunostaining also shows a decrease in DARPP-32 staining in the KI/Cas9 striatum by AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection. (D) Quantification of the number of NeuN-positive (from B) and DARPP-32–positive cells (from C) in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum of WT/Cas9 and KI/Cas9 mice, and in the AAV-control gRNA-injected striatum of KI/Cas9 mice. The data were obtained by counting 20 images from five animals per group. ***P < 0.001. (Scale bars, 15 μm [B]; 10 μm [C].)

Loss of Hap1 Increased Soluble Mutant HTT in the Striatum.

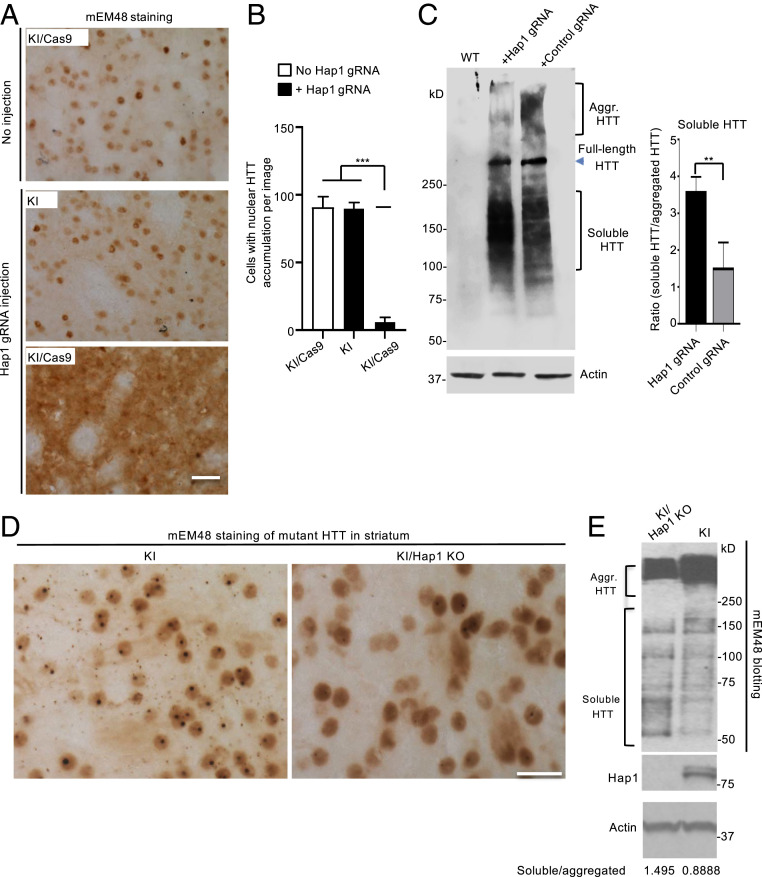

The preferential accumulation of mutant HTT in the striatum of HD KI mice mirrors the preferential neuronal loss in the striatum of HD patient brains (4, 5) and also allowed us to examine whether loss of Hap1 can influence the distribution of mutant HTT in the striatum. We found that in the AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum of KI mouse brain, there were less aggregated HTT and more soluble mutant HTT as compared with the striatum without AAV injection or with AAV-control gRNA injection (Fig. 5A). Quantitative assessment of cells with nuclear mutant HTT accumulation also confirmed the inhibitory effect of Hap1 deficiency on nuclear HTT accumulation (Fig. 5B). Western blotting further validated that AAV-Hap1 gRNA reduced the amount of aggregated mutant HTT and increased the level of soluble mutant HTT (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Loss of Hap1 in HD KI striatum reduces nuclear aggregated HTT and increases soluble mutant HTT. (A) mEM48 immunostaining showing that depletion of Hap1 by AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection reduced the accumulation of nuclear HTT and increased diffused mutant HTT in the striatum of a 6-mo-old KI/Cas9 mouse. The contralateral striatum region without injection in the same mouse and an age-matched KI mouse without Cas9 but injected with AAV-Hap1 gRNA served as controls. (B) Quantification of the number of cells with intense nuclear HTT accumulation. The data were obtained by counting 16 images (40X) from four animals per group. ***P < 0.001. (C) Western blotting (Left) shows the increased soluble mutant HTT and reduced HTT aggregates (Aggr. HTT) in the striatum of KI/Cas9 mice at 6 mo of age after AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection as compared with the control AAV-gRNA injection. (Right) The densitometric ratio of soluble HTT to aggregated (Agg.) HTT on Western blot (Left). The data are mean ± SEM (n = 3), **P < 0.01. (D) Tamoxifen-induced Hap1 depletion also reduced aggregated HTT and increased diffuse HTT distribution in the striatum in KI/Hap1 KO mice. KI/Hap1 KO mice were injected with tamoxifen at 3 mo of age and analyzed at 9 mo of age. (E) Western blotting also shows the reduced HTT aggregation (Aggr. HTT) and increased soluble HTT in the striatum when Hap1 was absent. The densitometric ratios of soluble HTT to aggregated HTT are shown beneath the Western blots. (Scale bars, 20 μm [A]; 15 μm [D].)

AAV viral delivery could induce cellular stress and toxicity to enhance mutant HTT toxicity. We wanted to use a different approach that can eliminate Hap1 expression without AAV viral transduction. Since germline Hap1 knockout (KO) mice do not survive in the postnatal stage (28), we established conditional Hap1 KO mice in which Hap1 depletion can be induced by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of tamoxifen (35). We crossed inducible Hap1 KO mice with HD KI mice to obtain those mice that carried both loxp-Hap1 allele/Cre-ER and mutant HTT gene (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). These crossed mice (KI/Hap1 KO) at the age of 3 mo were then injected with tamoxifen for five consecutive days. At 9 mo of age, we confirmed the depletion of Hap1 in the brain of KI/Hap1 KO mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Similar to AAV-Hap1 gRNA-injected striatum, tamoxifen-induced Hap1 depletion also reduced HTT aggregates and increased soluble mutant HTT (Fig. 5D), which is supported by Western blotting results showing that less aggregated HTT and more soluble HTT were present in the striatum when Hap1 was depleted (Fig. 5E). However, the alteration extent in HTT aggregation and soluble mutant HTT caused by tamoxifen-induced Hap1 depletion is not as great as that caused by AAV-Hap1 gRNA injection. Consistently, we did not observe obvious NeuN staining alteration in the KI mouse striatum following tamoxifen-induced Hap1 depletion (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). These differences suggest that neuronal loss caused by mutant HTT in the absence of Hap1 may also require cellular stress or insults, which could be induced by AAV viral infection.

Loss of Hap1 Increased the Binding of Rhes to Mutant HTT and the Level of Sumoylated HTT.

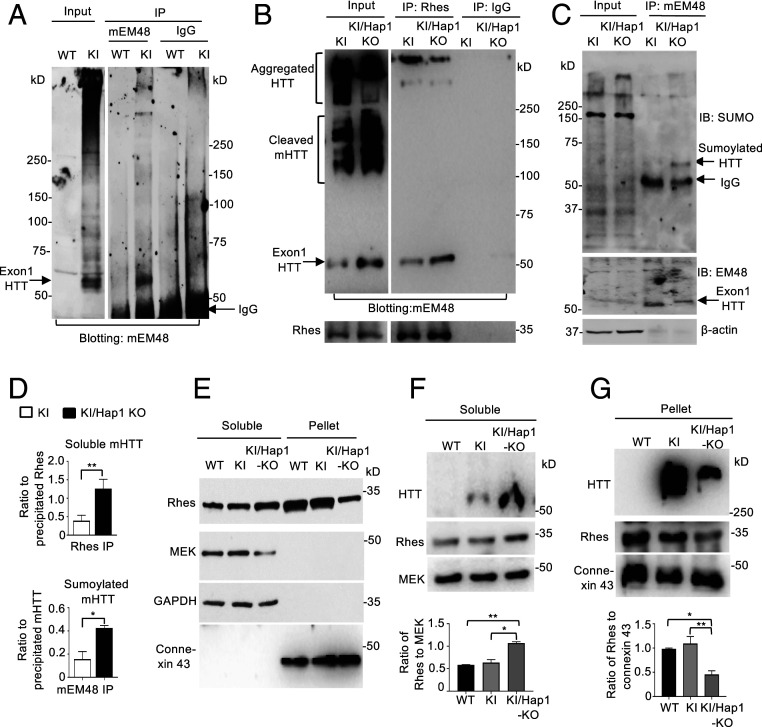

The finding that Hap1 deficiency can increase soluble mutant HTT and the fact that soluble polyQ proteins are more toxic than aggregated proteins (19, 20, 44) led us to explore the mechanism behand this interesting finding. Rhes is a GTPase enriched in the striatum (16, 17) and was found to bind soluble mutant HTT (19). The binding of Rhes to mutant HTT can sumoylate HTT to increase HTT toxicity (19). It is possible that Hap1’s association with mutant HTT may prevent Rhes from binding to HTT such that loss of Hap1 increases the binding of Rhes to mutant HTT and subsequent sumoylation of mutant HTT. To test this idea, we performed Rhes immunoprecipitation of HD KI striatum and wanted to know if Hap1 deficiency could influence Rhes-HTT binding. We have tried several batches of commercially available anti-Rhes and were able to immunoprecipitate Rhes (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Because homozygous Hap1 KO would significantly influence aggregated HTT in the brain tissue, which could confound the interpretation of the precipitated results, we used heterozygous Hap1 KO (Hap1+/−)/KI striatum for precipitation in order to evaluate whether Rhes binds aggregated and soluble mutant HTT differently. In HD KI mouse brain, multiple N-terminal HTT fragments are presented and can be detected by antibodies to HTT. However, the patterns of N-terminal HTT fragments on Western blots detected by different antibodies are not identical, suggesting that N-terminal HTT fragments may have different posttranslational modifications and conformations. We found that mouse EM48 antibody (mEM48) can recognize a small mutant HTT fragment in the HD KI mouse brain and could also immunoprecipitate it, which is equivalent to exon1 HTT (45) (Fig. 6A). In addition, we were able to use anti-Rhes to immunoprecipitate mutant HTT (Fig. 6B). Immunoprecipitation of Rhes showed that when Hap1 is deficient, less aggregated HTT and more soluble exon1 mutant HTT were coprecipitated by anti-Rhes (Fig. 6B). These findings also support the previous report that Rhes binds more soluble mutant N-terminal HTT (19).

Fig. 6.

Hap1 deficiency increases the binding of Rhes to soluble N-terminal mutant HTT and sumoylated N-terminal HTT. (A) Western blotting showing that mEM48 could specifically precipitate a small N-terminal HTT that is equivalent to exon1 HTT (arrow). (B) Rhes immunoprecipitation of mutant HTT from the striatum in 9-mo-old KI or KI/Hap1 KO mice. Note that the exon1-like HTT (arrow) was enriched in the precipitates as compared with other cleaved mutant HTT. Less aggregated HTT was precipitated by anti-Rhes. The blots were also probed with anti-Rhes (Lower). (C) Immunoprecipitation of mutant HTT by mEM48 from KI or KI/Hap1 KO mice at 9 mo of age. The immunoprecipitates were probed with an antibody to SUMO-1 and mEM48, revealing the increased sumoylated mutant HTT in the absence of Hap1. (D) Densitometric ratios of soluble mutant HTT to the precipitated Rhes (Upper) or sumoylated mHTT to precipitated mutant HTT (Lower) on Western blots in B and C. The data are mean ± SEM (n = 3), **P < 0.01. (E) Representative Western blotting images of fractionation of soluble proteins and pellets using 6-mo-old WT, KI, and KI/Hap1 KO mouse brain lysate. Antibodies against the cytosolic protein MEK and GAPDH or membrane protein connexin-43 were used to probe Western blots. (F) Mutant HTT and Rhes were increased in the soluble protein fraction in the Hap1-deficient KI mouse striatum (Upper). Densitometric ratios of Rhes to MEK were presented (Lower). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (G) Mutant HTT aggregates and Rhes were decreased in the pellet fraction, which is enriched in the nucleus and membranous organelles, in the Hap1-deficient KI mouse striatum (Upper). Densitometric ratios of Rhes to connexin-43 were presented (Lower). The data are mean ± SEM (n = 3), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To examine whether N-terminal HTT fragment that is equivalent to exon1 HTT can be sumoylated and whether lack of Hap1 may influence its sumoylation, we used mEM48 to immunoprecipitate mutant HTT and then analyzed the immunoprecipitates by Western blotting with an antibody to SUMO-1. The result showed that in the absence of Hap1, there was a marked increase in the sumoylated HTT (Fig. 6C). Quantification of the ratios of the coprecipitated soluble exon1 HTT to the precipitated Rhes or the sumoylated HTT to the precipitated mutant HTT verified that lack of Hap1 could increase soluble mutant HTT and its sumoylation (Fig. 6D). Mutant HTT aggregates can accumulate in the nucleus and associate with membranous organelles (46–50). If the binding of cytosolic Hap1 to soluble mutant HTT can prevent the interaction of Rhes with HTT in the cytoplasm, loss of Hap1 may increase the association of cytosolic Rhes with soluble mutant HTT and also reduce mutant HTT aggregates in the nucleus and membranous organelles. To test this idea, we isolated the soluble protein fraction via centrifugation of brain lysates at 15,000 × g, which could result in the pellet fraction that is enriched in the nucleus and membranous organelles (51) (Fig. 6E). By comparing with the cytosolic proteins GFAP and MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase) as well as the integral membrane protein connexin 43, we found that lack of Hap1 could significantly increase the soluble N-terminal HTT and Rhes (Fig. 6F). Consistently, in the pellet fraction, aggregated HTT was reduced with a parallel decrease in Rhes (Fig. 6G). Soluble mutant HTT appears to mediate greater toxicity than aggregated HTT by affecting a variety of cellular functions, including intracellular trafficking, mitochondria metabolism, synaptic transmission, and autophagic function (2, 3). Thus, it is possible that the binding of Hap1 to soluble mutant HTT in the cytoplasm prevents Rhes from interacting with mutant HTT and its subsequent sumoylation, therefore reducing HTT toxicity.

Discussion

The preferential degeneration in the striatum in HD represents a well-known but challenging issue to address, as selective neuronal loss in distinct brain regions was also seen in a number of neurodegenerative diseases caused by different types of disease proteins. Our findings suggest that multiple factors contribute to this selective neurodegeneration and also offer a potential therapeutic target for alleviating the selective striatal neuronal loss in HD.

In the current study, we provided the following lines of evidence to support the idea that loss of Hap1 selectively causes neurodegeneration in the striatum of HD KI mouse brain. First, deletion of Hap1 in the striatum of WT mice does not induce neuronal loss, and the expression of mutant HTT is required for Hap1 deficiency to cause neurodegeneration in the striatum. Second, the neuronal degeneration mediated by Hap1 depletion does not occur in other brain regions in HD KI mice, suggesting that tissue-specific factor(s) are also required for selective neurodegeneration. Third, AAV transduction-mediated Hap1 depletion causes more severe neuropathology than tamoxifen-induced Hap1 depletion, also suggesting that cellular stress and insults, which can be induced by AAV transduction, are required for striatal neuronal degeneration. Thus, the combination of the expression of mutant HTT, tissue-specific factor, and cellular stress or insults synergistically mediates the preferential neuronal loss in the striatum in HD.

The requirement of mutant HTT for Hap1 deficiency-mediated neuronal loss fits well with the fact that mutant HTT binds more tightly to Hap1 and can affect its normal function (6, 8, 11, 36, 37). The selective striatal neurodegeneration in HD KI/Hap1 KO mice is consistent with the preferential accumulation of mutant HTT in the striatum in HD KI mice. Although the mechanism underlying this preferential accumulation remains to be investigated, it is logical to link selective striatal degeneration to Rhes, a striatal-enriched GTPase that binds and sumoylates mutant HTT (19). We found that when Hap1 was deficient, more Rhes bound to mutant HTT and there was more sumoylated HTT, a toxic form of HTT that was found to affect cell viability (19, 20).

It is also interesting to know that AAV-Hap1 gRNA transduction can cause more severe neurodegeneration than tamoxifen-induced Hap1 depletion. The selective AAV-Hap1 gRNA-mediated neurodegeneration in the striatum is unlikely due to nonspecific effects of AAV transduction. This is because the same viral transduction did not cause neuronal loss in the WT mouse striatum or in the cortex and hypothalamus in the same HD KI mouse brain. In addition, the AAV-control gRNA did not induce any neuronal degeneration in the striatum of the same KI/Cas9 mice. However, when the Hap1 gene was depleted via tamoxifen-mediated recombination, we did not observe obvious neuronal loss. We think that AAV transduction-mediated cellular stress is more likely to enhance mutant HTT toxicity, because adenoviral infection is well known to induce cellular stress, immunity, inflammation, and cytotoxicity (52–56). Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that cellular stress, which can be induced by AAV transduction but may not be significantly toxic to normal neurons, can enhance mutant HTT toxicity and neuronal degeneration. This possibility also explains why striatal degeneration in HD is age-dependent and occurs in aged neurons that might have been exposed to cumulative cellular stress or insults during aging. Alternative possibilities also include that differences between conditional Hap1 KO and AAV transduction-induced Hap1 depletion account for differential neurodegeneration. AAV transduction by brain injection may more rapidly delete the Hap1 gene than tamoxifen-mediated Hap1 depletion in conditional Hap1 KO mice. The gradual loss of Hap1 in conditional KO mice may allow neuronal cells to produce compensatory responses to prevent or slow down degeneration.

Overexpression of Rhes via AAV transduction of brain neuronal cells was reported to be both toxic and protective in HD mouse models (25–27). However, the pathological role of Rhes in HD has also been supported by other studies of HD cellular models (57–59). Since Rhes is involved in multiple functions such as G protein and mTOR signaling, autophagy, and mitophagy (21, 22, 60), altering its expression via different approaches or under different disease conditions may lead to inconsistent outcomes for HD phenotypes. Despite these possibilities, biochemical studies have provided solid evidence that Rhes can bind mutant HTT, leading to more soluble mutant HTT and sumoylated HTT (19). Our studies suggest that loss of Hap1 can enhance the cytoplasmic Rhes’s binding to mutant HTT and increase the soluble mutant HTT in the cytoplasm. It is well known that polyQ expansion alters protein conformation to induce cytotoxicity (61). Soluble and aggregated mutant HTT have different conformations and elicit complex and adverse effects on multiple cellular functions. Large aggregates in axons and nerve terminals could physically block the transport and neurotransmitter release, while in the nucleus, soluble mutant HTT may be more toxic than aggregated HTT to affect gene expression. This is because soluble mutant HTT is more likely to abnormally interact with other transcription factors than HTT aggregates.

Our findings underscore the importance of the contribution of multiple cellular factors to selective neurodegeneration in neurodegenerative diseases, which should have implications for identifying the mechanisms underlying selective neurodegeneration in different neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, our findings suggest that improving Hap1’s function and expression in the aged striatal neurons may be beneficial for alleviating the striatal neuropathology in the HD patient brains.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Emory University. All mice were maintained in Emory University’s Division of Animal Resources (DAR) facility in a 12-h light/dark cycle-controlled room in accordance with IACUC and DAR policies.

Full-length mutant HTT KI (140CAG) (HD KI) mice were previously gifted from Michael Levine, UCLA, and used in our early studies (62). Cre-dependent Cas9 transgenic mice (34) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 024857, Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 KI) and were crossed to EIIA Cre-transgenic mice to generate Cas9-expressing mouse line that ubiquitously express Cas9 in all tissues. Germline transmissible Cas9 mice were isolated after more than three generations, and the resulting Cas9 mice were used for further studies. The HD KI mice were crossbred with Cas9 mice to obtain a mouse line expressing both mutant HTT and Cas9.

Germline Hap1-KO mice were generated in our early study (28). We generated conditional Hap1-KO mice by crossing the floxed Hap1 mice with Cre-estrogen receptor (ER) transgenic mice (B6.Cg-Tg[CAG-cre/Esr1]5Amc/J; The Jackson Laboratory), which have a tamoxifen-inducible Cre-mediated recombination system driven by the chicken β-actin promoter/enhancer coupled with the CMV immediate-early enhancer (30, 35). The inducible Hap1 KO mice were crossed with HD KI mice to generate inducible KI/Hap1 KO mice. To induce Hap1 depletion in adult conditional Hap1 KO mice, we used tamoxifen injection. Tamoxifen (TM, T5648; Sigma-Aldrich), which was dissolved in 100% ethanol as stock solution (20 mg/mL) and stored at −20 °C, was i.p. injected at 1 mg TM per 10 g body weight daily into the KI/inducible Hap1 KO mice at 3 mo of age for five consecutive days to generate KI/Hap1 KO mice. After tamoxifen induction, the animals were analyzed at the age of 9 mo.

AAV-gRNA Preparation.

PX552 viral vectors used for CRISPR/Cas9 experiments were obtained from Addgene (Addgene plasmid #60958). The following gRNA sequences were inserted into PX552 vectors to target Hap1 exon1: T2 (CTC CGG CCG ATG TAC GCG GC tgg) and T3 (ATG GAC CCG CTA CGT ATT CC agg) with PAM sequence represented in lowercase. The control gRNA (ACC GGA AGA GCG ACC TCT TCT) was previously generated in our study (62) and used as a control AAV-gRNA. The viruses were then packaged into AAV9 by the Viral Vector Core at Emory University.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 NS036232 and R01 NS101701), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81830032, 31872779, 81701281, and 2016YFC1306000), Key Field Research and Development Program of Guangdong province (2018B030337001), and Guangdong Key Laboratory of nonhuman primate models of brain diseases. We thank Jennifer Zhang for technical assistance.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2002283117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the main text and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Ross C. A., Tabrizi S. J., Huntington’s disease: From molecular pathogenesis to clinical treatment. Lancet Neurol. 10, 83–98 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates G. P. et al., Huntington disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1, 15005 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saudou F., Humbert S., The biology of huntingtin. Neuron 89, 910–926 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vonsattel J. P., DiFiglia M., Huntington disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 57, 369–384 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vonsattel J. P. et al., Neuropathological classification of Huntington’s disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 44, 559–577 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X. J. et al., A huntingtin-associated protein enriched in brain with implications for pathology. Nature 378, 398–402 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gauthier L. R. et al., Huntingtin controls neurotrophic support and survival of neurons by enhancing BDNF vesicular transport along microtubules. Cell 118, 127–138 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twelvetrees A. E. et al., Delivery of GABAARs to synapses is mediated by HAP1-KIF5 and disrupted by mutant huntingtin. Neuron 65, 53–65 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keryer G. et al., Ciliogenesis is regulated by a huntingtin-HAP1-PCM1 pathway and is altered in Huntington disease. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 4372–4382 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roux J. C. et al., Modification of Mecp2 dosage alters axonal transport through the huntingtin/Hap1 pathway. Neurobiol. Dis. 45, 786–795 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong Y. C., Holzbaur E. L., The regulation of autophagosome dynamics by huntingtin and HAP1 is disrupted by expression of mutant huntingtin, leading to defective cargo degradation. J. Neurosci. 34, 1293–1305 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackenzie K. D. et al., Huntingtin-associated protein-1 (HAP1) regulates endocytosis and interacts with multiple trafficking-related proteins. Cell. Signal. 35, 176–187 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X. J. et al., Huntingtin-associated protein (HAP1): Discrete neuronal localizations in the brain resemble those of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 4839–4844 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page K. J., Potter L., Aronni S., Everitt B. J., Dunnett S. B., The expression of huntingtin-associated protein (HAP1) mRNA in developing, adult and ageing rat CNS: Implications for Huntington’s disease neuropathology. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10, 1835–1845 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujinaga R. et al., Neuroanatomical distribution of huntingtin-associated protein 1-mRNA in the male mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 478, 88–109 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falk J. D. et al., Rhes: A striatal-specific Ras homolog related to Dexras1. J. Neurosci. Res. 57, 782–788 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargiu P. et al., Thyroid hormone regulation of rhes, a novel Ras homolog gene expressed in the striatum. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 94, 1–8 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spano D. et al., Rhes is involved in striatal function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5788–5796 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramaniam S., Sixt K. M., Barrow R., Snyder S. H., Rhes, a striatal specific protein, mediates mutant-huntingtin cytotoxicity. Science 324, 1327–1330 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steffan J. S. et al., SUMO modification of huntingtin and Huntington’s disease pathology. Science 304, 100–104 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramaniam S., Snyder S. H., Huntington’s disease is a disorder of the corpus striatum: Focus on Rhes (Ras homologue enriched in the striatum). Neuropharmacology 60, 1187–1192 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison L. M., Rhes: A GTP-binding protein integral to striatal physiology and pathology. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 32, 907–918 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baiamonte B. A., Lee F. A., Brewer S. T., Spano D., LaHoste G. J., Attenuation of Rhes activity significantly delays the appearance of behavioral symptoms in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. PLoS One 8, e53606 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mealer R. G., Subramaniam S., Snyder S. H., Rhes deletion is neuroprotective in the 3-nitropropionic acid model of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 33, 4206–4210 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swarnkar S. et al., Ectopic expression of the striatal-enriched GTPase Rhes elicits cerebellar degeneration and an ataxia phenotype in Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 82, 66–77 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J. H. et al., Rhes suppression enhances disease phenotypes in Huntington’s disease mice. J. Huntingtons Dis. 3, 65–71 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J. H. et al., Reinstating aberrant mTORC1 activity in Huntington’s disease mice improves disease phenotypes. Neuron 85, 303–315 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S. H. et al., Lack of huntingtin-associated protein-1 causes neuronal death resembling hypothalamic degeneration in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 23, 6956–6964 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeshita Y., Fujinaga R., Zhao C., Yanai A., Shinoda K., Huntingtin-associated protein 1 (HAP1) interacts with androgen receptor (AR) and suppresses SBMA-mutant-AR-induced apoptosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 2298–2312 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y. F., Xu X., Cape A., Li S., Li X. J., Huntingtin-associated protein-1 deficiency in orexin-producing neurons impairs neuronal process extension and leads to abnormal behavior in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15941–15949 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mele M., Aspromonte M. C., Duarte C. B., Downregulation of GABAA receptor recycling mediated by HAP1 contributes to neuronal death in in vitro brain ischemia. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 45–57 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zucker B. et al., Transcriptional dysregulation in striatal projection- and interneurons in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease: Neuronal selectivity and potential neuroprotective role of HAP1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 179–189 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Islam M. N. et al., Immunohistochemical analysis of huntingtin-associated protein 1 in adult rat spinal cord and its regional relationship with androgen receptor. Neuroscience 340, 201–217 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platt R. J. et al., CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell 159, 440–455 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiang J. et al., Huntingtin-associated protein 1 regulates postnatal neurogenesis and neurotrophin receptor sorting. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 85–98 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caviston J. P., Holzbaur E. L. F., Huntingtin as an essential integrator of intracellular vesicular trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 147–155 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rong J., Li S. H., Li X. J., Regulation of intracellular HAP1 trafficking. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 3025–3029 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayram-Weston Z., Jones L., Dunnett S. B., Brooks S. P., Light and electron microscopic characterization of the evolution of cellular pathology in HdhQ92 Huntington’s disease knock-in mice. Brain Res. Bull. 88, 171–181 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heng M. Y., Detloff P. J., Albin R. L., Rodent genetic models of Huntington disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 32, 1–9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin C. H. et al., Neurological abnormalities in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 137–144 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menalled L. B., Sison J. D., Dragatsis I., Zeitlin S., Chesselet M. F., Time course of early motor and neuropathological anomalies in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease with 140 CAG repeats. J. Comp. Neurol. 465, 11–26 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tallaksen-Greene S. J., Crouse A. B., Hunter J. M., Detloff P. J., Albin R. L., Neuronal intranuclear inclusions and neuropil aggregates in HdhCAG(150) knockin mice. Neuroscience 131, 843–852 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu Z. X. et al., Mutant huntingtin causes context-dependent neurodegeneration in mice with Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. 23, 2193–2202 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saudou F., Finkbeiner S., Devys D., Greenberg M. E., Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions. Cell 95, 55–66 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landles C. et al., Proteolysis of mutant huntingtin produces an exon 1 fragment that accumulates as an aggregated protein in neuronal nuclei in Huntington disease. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8808–8823 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X. et al., Mutant huntingtin impairs vesicle formation from recycling endosomes by interfering with Rab11 activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 6106–6116 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burke K. A., Kauffman K. J., Umbaugh C. S., Frey S. L., Legleiter J., The interaction of polyglutamine peptides with lipid membranes is regulated by flanking sequences associated with huntingtin. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14993–15005 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao X. et al., Cholesterol modifies huntingtin binding to, disruption of, and aggregation on lipid membranes. Biochemistry 55, 92–102 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaibva M. et al., Acetylation within the first 17 residues of huntingtin exon 1 alters aggregation and lipid binding. Biophys. J. 111, 349–362 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaibva M. et al., Sphingomyelin and GM1 influence huntingtin binding to, disruption of, and aggregation on lipid membranes. ACS Omega 3, 273–285 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah M., Patel K., Fried V. A., Sehgal P. B., Interactions of STAT3 with caveolin-1 and heat shock protein 90 in plasma membrane raft and cytosolic complexes. Preservation of cytokine signaling during fever. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45662–45669 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.St George J. A., Gene therapy progress and prospects: Adenoviral vectors. Gene Ther. 10, 1135–1141 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mian A. et al., Toxicity and adaptive immune response to intracellular transgenes delivered by helper-dependent vs. first generation adenoviral vectors. Mol. Genet. Metab. 84, 278–288 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gerner C. et al., Indications for cell stress in response to adenoviral and baculoviral gene transfer observed by proteome profiling of human cancer cells. Electrophoresis 31, 1822–1832 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma A., Bangari D. S., Tandon M., Hogenesch H., Mittal S. K., Evaluation of innate immunity and vector toxicity following inoculation of bovine, porcine or human adenoviral vectors in a mouse model. Virus Res. 153, 134–142 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barlan A. U., Griffin T. M., McGuire K. A., Wiethoff C. M., Adenovirus membrane penetration activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Virol. 85, 146–155 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu B., Palacino J., A novel human embryonic stem cell-derived Huntington’s disease neuronal model exhibits mutant huntingtin (mHTT) aggregates and soluble mHTT-dependent neurodegeneration. FASEB J. 27, 1820–1829 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okamoto S. et al., Balance between synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activity influences inclusions and neurotoxicity of mutant huntingtin. Nat. Med. 15, 1407–1413 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seredenina T., Gokce O., Luthi-Carter R., Decreased striatal RGS2 expression is neuroprotective in Huntington’s disease (HD) and exemplifies a compensatory aspect of HD-induced gene regulation. PLoS One 6, e22231 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma M. et al., Rhes, a striatal-enriched protein, promotes mitophagy via Nix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 23760–23771 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feng X., Luo S., Lu B., Conformation polymorphism of polyglutamine proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 43, 424–435 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang S. et al., CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing ameliorates neurotoxicity in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 2719–2724 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the main text and SI Appendix.