Significance

We report on cultivation and characterization of an association between Candidatus Nanohalobium constans and its host, the chitinotrophic haloarchaeon Halomicrobium LC1Hm, obtained from a crystallizer pond of marine solar salterns. High-quality nanohaloarchael genome sequence in conjunction with electron- and fluorescence microscopy, growth analysis, and proteomic and metabolomic data revealed mutually beneficial interactions between two archaea, and allowed dissection of the mechanisms for these interactions. Owing to their ubiquity in hypersaline environments, Nanohaloarchaeota may play a role in carbon turnover and ecosystem functioning, yet insights into the nature of this have been lacking. Here, we provide evidence that nanohaloarchaea can expand the range of available substrates for the haloarchaeon, suggesting that the ectosymbiont increases the metabolic capacity of the host.

Keywords: haloarchaea, nanohaloarchaea, polysaccharide utilization, symbiosis, solar salterns

Abstract

Nano-sized archaeota, with their small genomes and limited metabolic capabilities, are known to associate with other microbes, thereby compensating for their own auxotrophies. These diminutive and yet ubiquitous organisms thrive in hypersaline habitats that they share with haloarchaea. Here, we reveal the genetic and physiological nature of a nanohaloarchaeon–haloarchaeon association, with both microbes obtained from a solar saltern and reproducibly cultivated together in vitro. The nanohaloarchaeon Candidatus Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh is an aerotolerant, sugar-fermenting anaerobe, lacking key anabolic machinery and respiratory complexes. The nanohaloarchaeon cells are found physically connected to the chitinolytic haloarchaeon Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm. Our experiments revealed that this haloarchaeon can hydrolyze chitin outside the cell (to produce the monosaccharide N-acetylglucosamine), using this beta-glucan to obtain carbon and energy for growth. However, LC1Hm could not metabolize either glycogen or starch (both alpha-glucans) or other polysaccharides tested. Remarkably, the nanohaloarchaeon’s ability to hydrolyze glycogen and starch to glucose enabled growth of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm in the absence of a chitin. These findings indicated that the nanohaloarchaeon–haloarchaeon association is both mutualistic and symbiotic; in this case, each microbe relies on its partner’s ability to degrade different polysaccharides. This suggests, in turn, that other nano-sized archaeota may also be beneficial for their hosts. Given that availability of carbon substrates can vary both spatially and temporarily, the susceptibility of Halomicrobium to colonization by Ca. Nanohalobium can be interpreted as a strategy to maximize the long-term fitness of the host.

Hypersaline lakes and solar salterns with salt concentrations at or close to saturation host distinctive and unique consortia of extremely halophilic organisms. These microbial communities are often biomass-dense and phylogenetically diverse, including representatives of all domains of life, i.e., extremely halophilic bacteria and archaea, fungi, unicellular green algae, protists, and, quite often, arthropods (brine shrimps and in some cases also brine flies) (1). Such arthropods have chitinous exoskeletons and reach considerable biomass (up to 50 g⋅m−2), so chitin is one of the most abundant biopolymers in these ecosystems (2–5). Halophilic fermentative bacteria are known to play a role in chitin mineralization in hypersaline habitats worldwide (6–8), and more recently it has been shown that haloarchaea are also involved in the degradation of polymeric organic matter present in the habitat (8–12). Here, we show the additional role of chitinotrophic haloarchaea as hosts for nanohaloarchaea. These extremely halophilic organisms belong to the DPANN superphylum (named after the first members discovered: Diapherotrites, Parvarchaeota, Aenigmarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, and Nanohaloarchaeota) (13–17).

Members of phylum Ca. Nanohaloarchaeota were first detected less than a decade ago in 0.22-µm–filtered samples collected from Spanish solar salterns and the Australian hypersaline Lake Tirell (17, 18). Recent environmental surveys of 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) amplicons, metagenomic sequences, and lineage-specific quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of cells from natural samples indicate that nanohaloarchaea thrive in hypersaline ecosystems on a worldwide scale, including polyextreme habitats, such as eastern Mediterranean magnesium-saturated deep-sea brine lakes and Antarctic permanently cold hypersaline lakes (17–23). What is more, they often represent a notable fraction of the total archaeal community. Difficulties in the cultivation of DPANN members have prevented precise characterization of their growth requirements, physiology, and morphology, and there is a paucity of finished and curated genome sequences available for representatives of the superphylum. A few ectosymbiotic and ectoparasitic thermophiles from the candidate phylum Nanoarchaeota, and acidophiles from the candidate phylum Micrarchaeota, have been obtained in stable binary cocultures with their hosts from the phyla Crenarchaeota and Euryachaeota, respectively (24–27). Most recently, Hamm et al. (23) demonstrated enrichment of Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus in nutrient-rich medium supplemented with peptone and yeast extract, attempted to purifiy it from other species, and verified the maintenance of this nanohaloarchaeon, although unstable, in coculture with the heterotrophic haloarchaeon Halorubrum lacusprofundi. This development supports an earlier hypothesis that some haloarchaea may act as hosts for nanohaloarchaea (20). Given the phylogenetic diversity of these organisms, we suspect that nanohaloarchaeon–haloarchaeon interactions may subsist for diverse substrates and ecophysiological settings.

Here, we report the enrichment, cultivation, and characterization of a binary association of the nanohaloarchaeon LC1Nh, dubbed Ca. Nanohalobium constans (Ca. Nanohalobium for short), and its host, the chitinotrophic euryarchaeon Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm, from the hypersaline marine solar saltern Saline della Laguna (Trapani, Italy). We used the finished ungapped genome sequences in conjunction with electron microscopy, growth analyses, and proteomic and metabolomic data to study the euryarchaeon:nanohaloarchaeon interactions. In this way, we uncovered and dissected the mechanisms of (what turned out to be) the mutually beneficial relationship between these archaeal associates, providing evidence in support of the idea that nanohaloarchaea can be of environmental and ecological importance.

Results

Physicochemical Properties and Archaeal Composition of the Crystallizer Pond.

Near-bottom brine and surface sediments were collected from the artisanal, family-run solar saltwork Saline della Laguna. This saltern system is located near Trapani (western Sicily: 37°51′48.70′′N, 12°29′02.74′′E) and is one of the ancient sites of salt production known since the 7th century BC (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Sampling was done from the final crystallizer pond Vasca #27 (265 g⋅L−1 salinity, pH 7.2, 32 °C) in June 2016. The bottom layer of brine was microoxiic (0.11 ± 0.04 mg⋅L−1 dissolved oxygen), and the sediments were anoxic below 2 cm, containing millimolar concentrations of acid-labile sulfides (HS−/FeS). The ionic composition of the brine was typical for halite-dominated thalassohaline brines, originated from evaporation of seawater during solar saltwork (SI Appendix, Table S1). The major ions, except for calcium, were seven-fold more concentrated than the mean for Mediterranean seawater, suggesting an evaporation level of about 86% and that calcium sulfate and calcium carbonate precipitated during this process. The brine composition was in accordance with the solubility model (28, 29) developed for chemical evolution of the six-component seawater system during the evaporation path (30). At the time of sampling, the Vasca #27 brines were a pinkish color, and taxonomic analysis of the samples revealed that the microbial community was dominated by haloarchaea from the orders Halobacteriales and Haloferacales. Haloarchaea from six genera, Halorubrum (18%), Haloplanus (15%), Halobellus, Halococcus, Haloquadratum (10% each), and Natronomonas (7%) accounted for 70% of the in situ archaeal community in total, whereas Halomicrobium, which is discussed in more detail below, represented 3% of all archaeal sequences. Finally, members of Candidatus Nanohaloarchaeota were detected in the brine sample with a mean relative abundance of 1%.

Bringing Nanohaloarchaeota into the Culture.

Guided by hydrochemical data, the mineral medium Laguna Chitin (LC), pH 7.0 (240 g⋅L−1, 3.42 M Na+, and 0.37 M Mg2+), supplemented with amorphous chitin (2 g⋅L−1, final concentration), was used to enrich for chitinotrophic haloarchaea (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). After 3 mo of static incubation at 40 °C, the enrichment culture turned ultramicrooxic (0.08 ± 0.02 mg⋅L−1 dissolved oxygen). This initial enrichment was further subcultured by transferring 1 mL of inoculum to 100 mL of fresh LC broth supplemented with the bacterium-specific antibiotics vancomycin and streptomycin (100 mg⋅L−1, final concentration), followed by incubation in a tightly closed 120-mL serum bottle at 40 °C without shaking. Chitin particles rapidly acquired a pinkish color, indicative of a haloarchaeal biomass that appeared to be attached to the chitin. After 1 mo of cultivation, the 1:100 passage was carried out once more, and the amplicon sequencing of 16S rRNA genes revealed that throughout the course of these steps, the third enrichment culture became dominated by members of the subphylum Candidatus Nanohaloarchaeota and the haloarchaeal genus Halomicrobium, accounting for >50% of the total chitinotrophic community.

In attempts to obtain axenic cultures of both organisms, a dilution-to-extinction technique was applied, ensuring the isolation of numerically dominant types. The presence of nanohaloarchaea in grown dilutions (LC broth) was monitored by taxon-specific PCR, while growth of the chitinotrophic host was readily discernible due to a visible reddening of the diluted culture that coincided with the disappearance of chitin. The dilution-to-extinction procedure was repeated two more times, and then the last dilution (10−9), positive only for a chitinotrophic host, was plated onto LC agar supplemented with amorphous chitin as a sole carbon source (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The developed colonies of the axenic Halomicrobium culture formed large clearance zones, indicative of the extracellular production of chitin hydrolases. In parallel, the enrichment, obtained from the 10−8 dilution, underwent three rounds of filtering through a 0.45-µm membrane filter to obtain a fraction composed of unattached nanohaloarchaeal cells, separated from the chitinotrophic host, as it was determined by taxon-specific PCR analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). All subsequent attempts to cultivate the nanohaloarchaeon alone failed, despite using a variety of substrates and conditions. These attempts included the addition of either the Halomicrobium biomass lysate or the spent medium (see Materials and Methods for details). On the other hand, mixing the membrane-filtered nanohaloarchaeal cell suspension with an axenic culture of the Halomicrobium gave rise to a reconstructed coculture. Thus, the presence of a haloarchaeal host appears to be a prerequisite for successful cultivation of nanohaloarchaea under a defined set of conditions, but not vice versa. The reconstructed coculture was used to carry out physiological and biochemical studies of these organisms, as described below. Remarkably, the presence of nanohaloarchaeota in the reconstructed (binary) coculture grown on chitin seemed very stable. As revealed by taxon-specific PCR analysis, nanohaloarchaeota are able to survive prolonged storage (since their 16S rDNA gene amplicons were detected in coculture samples stored at for least 250 d in the dark at a room temperature of about 25 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Sequencing of amplified and cloned 16S rRNA genes revealed that the haloarchaeon (strain LC1Hm) has two dissimilar 16S genes, rrnA and rrnB, which differ by 96 nucleotides (i.e., 6.5% of the total). Phylogenetic analysis of these genes indicated that the strain LC1Hm was most closely related to Halomicrobium mukohataei DSM 12286T, Halomicrobium katesii DSM 19301T, and several other Halomicrobium isolates known to possess chitinolytic activities (10), with 96.7 to 99.3% of sequence identity (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Observed intraspecific polymorphism of 16S rRNA genes from LC1Hm is common to all known members of the genus Halomicrobium, with the 9% divergent 16S rRNA genes detected in the type species of the genus, H. mukohataei (31). A phylogenetic tree was constructed from the alignment of the 16S rRNA gene of the putative nanohaloarchaeon (strain LC1Nh) to the master alignment in SILVA Release 132SSURef NR99 (32) and inferred using maximum parsimony criteria within the ARB software (33) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This suggested that the nearest neighbor of the novel nanohaloarchaeon was the partially sequenced Cry7_clone28 (GenBank GQ374969, 94.3% identity) from the Dry Creek crystallizer pond (Australia) and other partially sequenced clones (∼91% identity) from around the world, all belonging to clade III of the candidate phylum Nanohaloarchaeota. According to the rRNA phylogeny, the LC1Nh nanohaloarchaeon is distinct from the other candidate genera in the phylum (86.5 to 91.8% sequence identities) and falls within the range of recently recommended values (86.5 and 94.5%) for family- and genus-level classifications (34). This was confirmed by a phylogenomic analysis of a concatenated alignment of the 122 single-copy archaeal marker genes using the Genome Taxonomy DataBase framework (35). The Nanohaloarchaeota phylum appears to be split into three class-level taxa. One class of this cluster comprises the previously cultivated Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus (23), while the other includes our cultivated representative of the Nanohaloarchaeota. The third cluster comprises Ca. Nanosalinarum of uncertain taxonomic rank and currently lacks cultivated representatives (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Herewith, we propose a new class, Ca. Nanohalobia, that includes a new order, Ca. Nanohalobiales, and the novel family, Ca. Nanohalobiaceae, which accommodates the genus Ca. Nanohalobium.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic placement of Ca. Nanohalobium based on concatenated partial amino acid sequences of the 122 proteins conserved in Archaea (archaeal marker genes). Bootstrap values are shown at the nodes; the bar indicates 0.20 changes per position. Cultivated and uncultured members of the candidate phylum Nanohaloarchaeota are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. A detailed list of DPANN genomes and the methods used for the tree construction are given Materials and Methods.

Microscopy of the LC1Nh+LC1Hm Association.

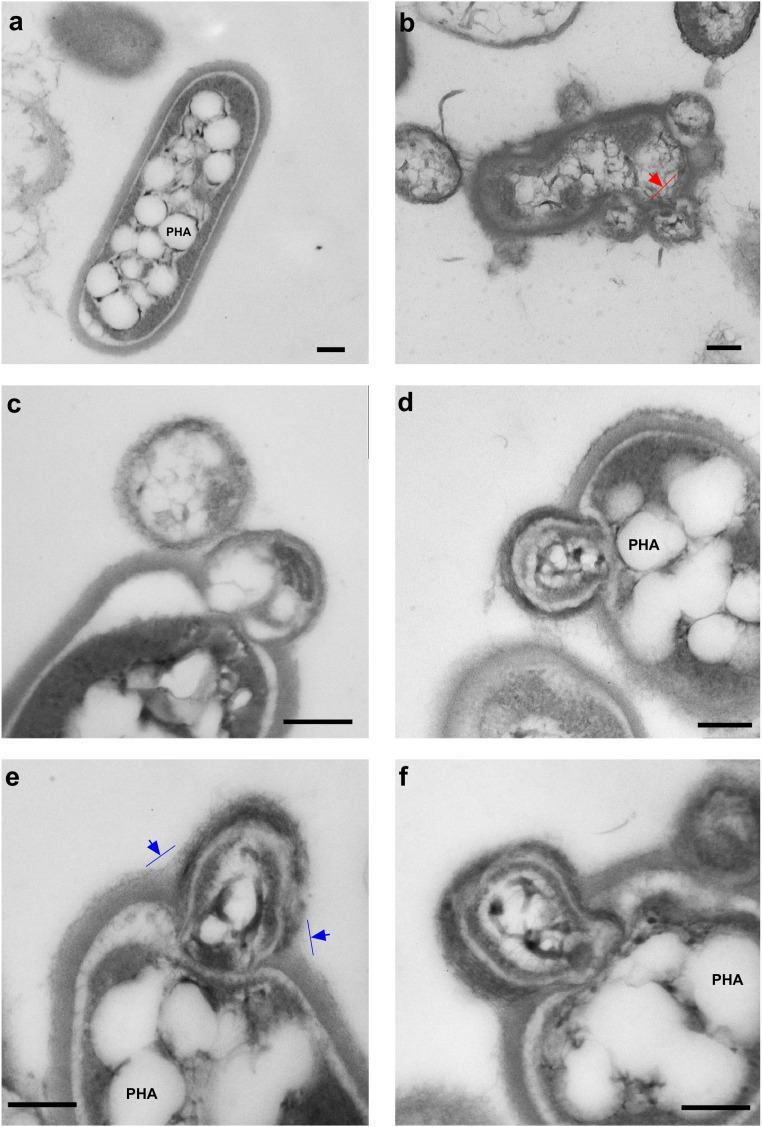

The LC1Nh nanohaloarchaeon was visualized, by fluorescence microscopy using conventional DAPI staining and catalyzed reporter deposition-FISH in the reconstructed coculture, as small coccoid cells either separated or associated with host cells that were pleomorphic, a characteristic of all Halomicrobium species (36) (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) revealed a regular S-layer–like outer surface of the nanohaloarchaeal cells. These small cocci formed an association with almost 20% of the cells within the Halomicrobium population at a media multiplicity of 4 to 5, but occasionally reaching 17 cells per host cell. In some cases, a single nanoarchaeon cell bridged two otherwise individual host cells. When grown on chitin, Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm cells produced a thick, electron-dense external layer, which often engulfed the symbiont (Fig. 3). Such extracellular material was not observed during growth on monosaccharides or disaccharides (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), suggesting that this layer is involved in the interaction of the host cells with the chitin particles, as was reported for cellulolytic natronoarchaea of the genus Natronobifoma (37). Another feature was the production of numerous intracellular granules, which was observed only during the growth of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm on chitin. Staining with Nile Blue A combined with fluorescent microscopy revealed brightly fluorescent orange granules (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), confirming that the chitinotrophic Halomicrobium LC1Hm cells accumulated polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) as carbon- and energy-storage material.

Fig. 2.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm and Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh coculture growing in the LC medium supplemented with chitin. Images depict tiny coccoidal nanohaloarchaeal cells (285 ± 50 nm in diameter) either detached or adhered to the host haloarchaeal cells. Up to 17 nanohaloarchaeota cells can closely interact with the single host cell (A–D); nanohaloarchaeal cells express the pilus-like structures (thick and long protein stalks of the archaella) (A, D, and E), which can unwind to thin filaments at the points indicated by red arrows.

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of chitin-growing coculture of Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh and Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm. (A) symbiont-free Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm cell. (B–F) Images of pronounced interaction (fusion) between Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm and Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh cells. The ectosymbiont causes evident membrane stretching (red arrow) and is often engulfed by extracellular matrix (blue arrows). PHA: granules of polyhydroxyalkanoate. (Scale bars: 200 nm.)

Thin-section TEM imaging of the LC1Nh+LC1Hm coculture revealed various aspects of cell contact between the nanohaloarchaeon and the host. The surface attachment with a visibly separated boundary was frequently accompanied by stretching of the host membrane (see Fig. 3B as an example). In some micrographs, there are clear signs of nanohaloarchaeon penetration of the host S-layer and even occasional breaching of the host's cell membrane (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). In addition, TEM and FESEM images of nanohaloarchaeal cells showed archaella-like structures made of thick and long monotrichous or ditrichous protein stalks, frequently unwinding to thin filaments (Fig. 2). It remains to be seen whether these structures are used for motility of unattached nanohaloarcheal cells or perform (an) alternative role(s), such as attachment to the polysaccharide substrate and/or host cells.

Growth Physiology of the LC1Nh+LC1Hm Coculture.

In both the axenic culture of the host, and in the host–ectosymbiont coculture, the externally added chitin was completely degraded after less than 2 wk of incubation in LC broth at 40 °C. High performance anion exchange chromatography was used to determine absence or presence and to quantify breakdown products of chitin present in the broth of these two cultures during the midexponential growth phase. The monomeric intermediate of chitin degradation, N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), was found in supernatants of both culture media at relatively high (and similar) concentrations: 3.71 ± 0.90 and 5.20 ± 1.61 mmol, respectively. In contrast, none of the low-molecular-weight chitodextrin oligomers, (GlcNAc)2–6, was detected. The presence of the ectosymbiont in a coculture slightly prolonged the growth lag phase of the host, a phenomenon that implies an adaptation period although not necessarily (biotic or abiotic) stress (38). Indeed, neither the maximum specific growth rates (0.028 to 0.035 h−1) nor the yield of the host biomass were affected (Fig. 4). Further differences in physiology of Halomicrobium cultured in the presence and absence of the nanohaloarchaeal ectosymbiont are also of interest. Namely, the growth of host–ectosymbiont association on chitin was accompanied by a three-fold higher accumulation of acetate (6.39 ± 1.55 vs. 2.10 ± 0.33 mmol, P = 0.002), as compared with the axenic growth of the host. The host–ectosymbiont association also consumed oxygen almost twice as fast as the pure Halomicrobium culture (P ≤ 0.009), resulting in microoxic conditions at the early stationary phase of growth (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Text). Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm did not grow anaerobically, consistent with published reports on other members of the genus Halomicrobium (10, 39), such as H. katesii, H. mukohataei, and Halomicrobium sp. HArcht3-1 and with our experiments, in which none grew by fermentation of chitin, N-acetylglucosamine, or glucose. In a separate experiment, we have established that the nanohaloarchaeon did not reproduce under the well-oxygenated regime of cultivation that was optimal for the axenic culture of the host (>4 mg⋅L−1 dissolved oxygen). Thus, only microoxic conditions enabled the growth of both organisms in a coculture. In addition to the requirement for low-oxygen tension, significant amounts of magnesium were needed for the prosperity of the host–ectosymbiont coculture; the host–ectosymbiont coculture can be stably maintained only at ≥75 mM Mg2+ concentrations. Unlike the LC1Hm host, which is extremely Mg2+-tolerant, 800 mM Mg2+ appears to be the upper limit for Ca. Nanohalobium growth (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

Fig. 4.

Growth of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm in pure (axenic) culture and in coculture with Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh: (A) Growth on chitin. (B) Growth on starch. (C) The oxygen consumption of axenic LC1Hm and LC1Hm + LC1Nh cultures during growth on chitin. (D and E) The concentration of acetate and reduced sugars, N-acetylglucosamine, and glucose in the supernatants during the midexponential and stationary phases of growth on chitin and starch, respectively. The overall significance level P < 0.01 is shown by single asterisks. Plotted values are means, and error bars (SDs) are based on three culture replicates.

None of other polysaccharides tested (cellulose, starch, glycogen, and xylan) supported the growth of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm in pure culture, so it came as a surprise to us that the host–ectosymbiont coculture grew rapidly on the alpha-glucans, starch, and glycogen. The growth rates on these two substrates were comparable to (µmax in the range of 0.043 to 0.066 h−1), or even exceeded, growth rates of either the pure Halomicrobium culture or the coculture on chitin (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). As in the case of chitin, degradation of starch was not accompanied by the release of measurable amounts of oligomers; the only detected hydrolysis product was monomeric glucose (≤4.61 ± 0.81 mmol) (Fig. 4E).

To test whether Ca. Nanohalobium has a specific adaptation to its host Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm, we mixed the three-times 0.45-µm–filtered Ca. Nanohalobium cells with pure cultures of other polysaccharidolytic haloarchaea belonging to all known orders of the class Halobacteria, such as chitinolytic Natrinema sp. HArcht2 and Salinarchaeum sp. HArcht-Bsk1, cellulolytic Halomicrobium zhouii HArcel3 (10), amylolytic Halorhabdus thiamatea (40), and sugar-utilizing haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii DSM3757. We failed to produce any coculture because the nanohaloarchaeon could not be detected after 1 mo of incubation, as assessed by taxon-specific PCR analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). In contrast, two chitinolytic representatives of the genus Halomicrobium, H. mukohataei JCM9738T, and Halomicrobium sp. HArcht3-1 (10) were successfully accepted as the hosts by Ca. Nanohalobium cells, creating the stable (binary) cocultures while growing on chitin as the sole carbon and energy source. Based on these findings, we named this nanohaloarchaeon Candidatus Nanohalobium constans; the nanosized salt-loving life form, constant in its specificity to the particular [chitinotrophic] members of the particular genus.

Genomic and Proteomic Analyses of the Ca. Nanohalobium–Halomicrobium Association.

We succeeded in the assembly and closure of the complete host Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm genome with the DNA isolated from the coculture and from the axenic host culture, with identical resulting sequences. In turn, the nanohaloarchaeal metagenome assembled genome (MAG) was assembled in its entirety from both the enrichment and reconstructed host–symbiont coculture DNA samples, yielding sequences that were identical. For both genomes, an overview of their characteristics is provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Tables S2, S3, and S4). Based on cultivation data and the genome analysis, Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm can be characterized as a typical heterotrophic haloarchaeon, possessing prototrophism for all metabolic building blocks essential to life in axenic culture (SI Appendix, Text).

The genome of Ca. Nanohalobium consists of a single circular chromosome of 973,463 bp with 43.2% of guanine-cytosine molar content and contains single copies of 5S, 16S, and 23S rRNA genes located in three different loci, as well as 39 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes. Of the 1,162 annotated protein-coding genes, 392 (33.7%) could be assigned to a functional category according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) resource, and 732 (63.3%) were assigned to the archaea-specific orthologous groups (arCOGs). Despite substantial genome completeness, indicated by a lack of gaps, the presence of tRNAs for all amino acids, and identification of the complete set of ribosomal proteins, we identified only 177 genes of 219 that constitute the core set of arCOGs (41), which is a feature of all known DPANN organisms that have experienced extensive gene loss (15, 16, 42). More specifically, the genome analysis of Ca. Nanohalobium predicts the lack of operational genes for de novo synthesis of all principal metabolic precursors, such as amino acids, nucleotides, lipids, and enzyme cofactors (SI Appendix, Text), underscoring its reliance on other extreme halophiles in providing these metabolic building blocks. Like most other small bacterial and archaeal genomes, and including those of other DPANN members, the nanohaloarchaeon LC1Nh genome has retained complete sets of the core genes involved in chromosome replication and maintenance as well as transcription machinery, ribosomal proteins, and translation factors (15, 16).

Acidification of intracellular proteins is a common adaptive feature of extremely halophilic prokaryotes possessing the salt-in strategy for maintaining the osmotic balance, i.e., the accumulation of molar-range concentrations of potassium within cells (1, 6). Calculations of the median isoelectric point (pI) for all proteins predicted in Ca. Nanohalobium and Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm yielded similar (acidic) values of pI 4.32 and pI 4.70, respectively. In agreement with the salt-in strategy for osmotic adjustment, the genome of LC1Nh encodes at least two types of K+ transporter (Kef and Trk), but lacks transporters for known organic compatible solutes that can be used as osmolytes (SI Appendix, Text). We calculated acidic proteomes for all publically available Nanohaloarchaea (SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S6), and the salt-in strategy of maintaining osmotic balance is a trait of the whole taxon, as proposed previously (17–20).

Inspection of the Ca. Nanohalobium genome allowed us to identify the genes implicated in the energy flow and key reactions that drive the biomass production. The ectosymbiont lacks genes for xenorhodopsin biosynthesis, which occurs in some nanohaloarchaeal MAGs (18). Furthermore, the Ca. Nanohalobium genome contained no genes coding for known components of carbon-fixation pathways, but possesses all enzymes of glycolysis and conversion of pyruvate into lactate, malate, ethanol, and acetate. The absence of membrane-bound proton-translocating pyrophosphatases suggests that Ca. Nanohalobium may rely on the A-type ATPase, the Kef-type potassium-hydrogen antiporter, and possibly other as-yet-unidentified systems that function as outward proton-translocating pumps to maintain chemiosmotic membrane potential (all information on gene IDs is in SI Appendix, Text). In agreement with the cultivation data and the absence of genes coding for any known components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and any of respiratory complexes, Ca. Nanohalobium can be classified as an aerotolerant anaerobe, capable of sugar fermentation (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Table S7).

Fig. 5.

Reconstruction of central metabolic and homeostatic functions of Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh based on genomic, proteomic, targeted metabolomic, and physiological analyses. Enzymes involved in energy production and in reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis/redox regulation are highlighted in yellow. Chitin degradation enabled by seven extracellularly expressed GH18 endochitinases and one GH20 chitodextrinase of the host, is indicated by the gray arrow in the lower-right part of the figure. Depolymerization of (1 → 4)- and (1 → 6)-alpha-d-glucans by two experimentally confirmed extracellularly expressed glucoamylases of Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh is shown with the green arrow in the upper-left part of the figure. The mutualistic uptake of the formed sugars is indicated by the red arrow. Compounds abbreviations: Asp, aspartate; a-KG, alpha ketoglutarate; 1,3BPG, 1,3-biphosphoglycerate; CoA, coenzyme A; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; F-6P, fructose-6-phosphate; F1,6BP, fructose-1,6-biphosphate; Glc-6P, glucose-6-phosphate; Glc-1P, glucose-1-phosphate; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-glucosamine; GlcNAc-6P, N-acetyl-glucosamine-6-phosphate; GlcN-6P, N-glucosamine-6-phosphate; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; OA, oxaloacetate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 2PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenol pyruvate; Prx, peroxiredoxin; Trx, thioredoxin. Genes and systems abbreviations: ACL, acetate-CoA ligase; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; AK, adenylate kinase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AVD, diversity-generating retroelement protein; CLec, C-type lectin fold; DGR, diversity-generating retroelements system; Dsb, disulfide bond formation; GNFAT, glucosamine–fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase; ENO, enolase; FBPA, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase; G1P, glucose-1-phosphatase; GAPD, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GDE, glycogen debranching enzyme; GH, glycogen hydrolase; GNPAT, bifunctional UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphatase; GPUT, UTP-glucose-1-phosphateuridylyltransferase; GS, glycogen synthase; HK, gluco(hexo)kinase; LamG, laminin G domain; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MaE, malic enzyme; MFS, major facilitator superfamily; MSRA, peptide-methionine (S)-S-oxide reductase; MSRB, peptide-methionine (R)-S-oxide reductase; NOX, pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; PEPS, phosphoenolpyruvate synthase; PGI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; PGM, 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; PF/GK, phosphofructokinase/glucokinase; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RT, reverse transcriptase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TIM, triosephosphate isomerase; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase. Details on genes and systems abbreviations are provided in SI Appendix, Table S7.

Cell-Surface Structures of Ca. Nanohalobium.

Transmission and scanning electron microscopy, together with the apparent absence of many anabolic genes, indicate that Ca. Nanohalobium likely relies on its physical contact with the chitinolytic host. We therefore expected that the LC1Nh genome would contain genes encoding cell-surface structures that enable its interactions with its host. Such interactions are likely mediated in DPANN relatives by extracellular and/or membrane-associated proteins, including archaella, lectins (carbohydrate-binding proteins), and other proteins that may interact directly with the host cell (15, 16, 23–27). In agreement with the observations of pilli-like structures, similar in appearance and size to protein stalks of the archaella (Fig. 2), the LC1Nh genome contains at least 20 genes likely encoding for the archaella assembly machinery and filament proteins (SI Appendix, Table S7). More than a half of these genes are organized in one operon harboring the archaeal flagellar proteins FlaG, FlaI, FlaJ, and FlaJ2 and seven hypothetical proteins and resembling the structure of euryarchaeal archaellum operons (43). In addition to archaella-related proteins, the LC1Nh genome encodes eight strain-specific secreted proteins, containing polycystic kidney disease and Con A-like/lectin LamG domains. Proteins that contain such domains serve a variety of purposes, often mediating interactions with carbohydrates or glycosylated proteins, and are likely involved in surface interactions in DPANN organisms, including nanohaloarchaeota (15, 16, 23, 26).

In order to overcome any host resistance to colonization, some proteins involved in host–symbiont interactions may be expected to rapidly evolve. Thus, any mechanism that is able of generating high diversity in specific loci may be of interest as a potential host–symbiont interaction determinant (44, 45). In agreement with this, several sequences related to the diversity-generating retroelements (DGRs) locus were found in the LC1Nh genome (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 and Text). This versatile tool for protein diversification that might be involved in mediating the interaction between ectosymbiont and host seems to be prevalent in several DPANN lineages, but has not been reported in Nanohaloarchaeota previously. We found that the DGR variable proteins of Ca. Nanohalobium belong to the formylglycine-generating enzyme subclass with a C-type lectin (CLec)-fold. This finding corroborates with the recent observation of remarkable conservation in archaea of the ligand-binding CLec-fold for accommodation of massive sequence variation created by DGRs (44, 45).

Omics-Inferred Trophic Relations in Halomicrobium–Ca. Nanohalobium Association.

As seen from genome analysis, degradation of chitin by Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm is mediated by an extensive enzymatic apparatus that is encoded by multiple loci, and is comprised of seven glycosyl hydrolases (GHs) from class III of the GH18 family of endochitinases (Enzyme Commission [EC 3.2.1.14]) (SI Appendix, Table S8). Six of the glycosyl hydrolases possess N-terminal Tat secretion signals and ChtBD3 chitin-binding domains but no transmembrane helices, indicating that they likely are extracellular; suitably positioned for digestion of environmental chitin. The simultaneous expression of these extracellular endochitinases (confirmed by their identification among secreted proteins, using proteomic methods) indicates that they may have distinct biochemical properties and act synergistically to break down the chitin microfibrils at internal sites. Terminal degradation of chito‐oligosaccharides to GlcNAc is expected to occur by the action of extracellular exochitodextrinase, annotated as β-N-acetylglucosaminidase of the GH20 family (EC 3.2.1.52), which contains the N-terminal Tat signal peptide, a ChtBD3 chitin-binding domain, and a polycystic kidney disease (PKD) repeat.

Access to high amounts of exogenous GlcNAc, produced by the host during chitinolytic growth, appears to be extremely important for the LC1Nh nanohaloarchaeon. The main path of its energy gaining likely begins with uptake of exogenous GlcNAc by one of three uncharacterized ABC-2 type transporters and/or by a major facilitator superfamily permease (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Text). Ca. Nanohalobium has a full set of enzymes responsible for transforming this monosaccharide into fructose-6-P that can then enter central carbohydrate metabolism via the archaeal version of the dissimilative Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway of glucose degradation. Oxidation of glucose to pyruvate involves the reduction of NAD+ to NADH, and thus, to avoid stopping glycolysis, the LC1Nh cells may have to reoxidize the metabolically unused excess of this reduced electron/energy shuttle. There are multiple indications from the LC1Nh genome that pyruvate could be also used in the reductive pathway as an electron acceptor via NADH-dependent reduction by lactate dehydrogenase, NAD-dependent malic enzyme, or short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase.

As stated above, the axenic culture of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm refused to grow on starch and glycogen, but did grow on these alpha-glucans in association with nanohaloarchaeon LC1Nh (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The genomic and proteomic data have helped to unravel this conundrum. The Ca. Nanohalobium genome encodes a complete set of enzymes for the archaeal type of gluconeogenesis, glycogen synthesis, and glycogen catabolism (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Table S7 and Text). Regarding the catabolism of glycogen, three different glycosyl hydrolases were found in the genome, in the cellular proteome, and in the coculture secretome; i.e., the glycogen-debranching enzyme, the alpha-amylase, and the glucan-1,4-alpha-glucosidase of GH15 family. In agreement with cultivation data and detection of monomeric glucose in the spent culture, the extracellular location of these glycosyl hydrolases suggests that they mediate the cleavage of both alpha-1,4 and alpha-1,6 glycosidic linkages, present in exogenous glycogen, thereby producing glucose extracellularly. This monosaccharide, produced by the combined activities of the nanohaloarchaeal hydrolases outside the cells, would ensure the growth of the host, thus enabling the Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm + Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh association to utilize these polysaccharides as an alternative to chitin.

Discussion

Studies of metabolic capacities, nutritional requirements, and ecological roles of DPANN archaea are still in their infancy. Members of this superphylum are abundant and globally ubiquitous, and crude and unassembled genome sequences of many of them indicate partnerships such as exosymbiosis with archaea of diverse phylogenetic lineages (15, 16, 23–27). Cultivation is essential for a proper characterization of such interspecies interactions, but only a handful of representatives of the superphylum have been grown in the laboratory, mostly in binary associations or within more biodiverse enrichments (23–27). In the current study, the nutrient medium enrichment culture from the brine and sediments of the solar saltwork crystallizer pond was selected to favor chitinolytic haloarchaea. The culture eventually became enriched in members from the genus Halomicrobium and, concomitantly, nanohaloarchaea (>30% of total archaeal population). The dilution-to-extinction approach, followed by filtration and coculture reconstruction, was recently successfully applied for isolation of the nanoarchaeon Ca. Nanoclepta minutus with its host, the thermophilic crenarchaeon Zestosphaera tikiterensis (27). Here, we applied a similar strategy and obtained a binary culture of a nanohaloarchaeon, Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh, with its haloarchaeal host, Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm, and elucidated the ecophysiological basis of their interaction.

Ca. Nanohalobium has a rudimentary anabolic capability and is devoid of the minimal enzyme sets required for biosynthesis of nucleotides, amino acids, lipids, vitamins, and cofactors. Thus, association with the host is essential for the growth of this nanohaloarchaeon. Moreover, this association seems be very specific, since, among tested polysaccharidolytic and sugar-utilizing haloarchaea, only chitinolytic members of the genus Halomicrobium were accepted by Ca. Nanohalobium as alternative hosts. The basis of this interaction, relying on either specificity of GlcNAc-releasing chitin degradation or other aspects of the host cell biology, remains to be elucidated. In addition to providing nucleotides, amino acids, lipids, vitamins, and cofactors, the production of extracellular GlcNAc (via depolymerization of chitin) seems an important prerequisite for the well-being of Ca. Nanohalobium. Complete hydrolysis of insoluble chitin to its monomer usually occurs via action of two types of hydrolytic enzymes: endochitinases, which digest chitin microfibrils at internal sites to form chitodextrins, and N,N′-diacetylchitobiose and exochitodextrinases, which further break down chitodextrin oligomers at their termini to produce the monosaccharide (8). The second phase of hydrolysis typically occurs in the periplasm or cytoplasm, and there are only a few indications that chitinitrophic halo(natrono)archaea are able to perform this process outside the cell (10).

In our case, the experimentally proven availability of external GlcNAc for Ca. Nanohalobium is indeed an important factor for its growth. Based on cultivation-derived and omic data, it seems that exogenous GlcNAc promotes the vitality of the LC1Nh nanohaloarchaeon via a dual action. We propose that this amino sugar can serve not only as the main source of energy conservation, but also as an anabolic precursor for protein and lipid glycosylation in Ca. Nanohalobium. Many organisms, including the geothermal DPANN nanoarchaeon Nanopusilis acidilobi (25), use N-acetylglucosamine in their surface glycosylation. The LC1Nh genome encodes 11 different glycosyl transferases belonging to the families GT1, GT2, and GT8, the majority of which are expressed judging from the proteomics data (Extended Dataset S2 A and B). Among 283 predicted surface proteins, nearly two-thirds possess putative glycosylation sites, indicating that posttranscriptional modifications may play an important role in Ca. Nanohalobium (Extended Dataset S1E). Considering that glycosylation processes and synthesis of activated sugars require substantial amounts of ATP, direct usage of exogenous GlcNAc has an obvious energetic advantage.

The genome of Ca. Nanohalobium harbors all key enzymes for gluconeogenesis and glycogen synthesis. This type of carbon and energy storage is considered to be a hallmark of DPANN organisms, including the nanohaloarchaea (15, 16), but is absent in all known members of extremely halophilic archaea. Glycogen-storing organisms obviously have enzymatic capabilities to mobilize/catabolize this compound. Indeed, in addition to the glycogen-debranching enzyme and alpha-amylase, the Ca. Nanohalobium genome encodes the glucan-1,4-alpha-glucosidase. The extracellular location of these three proteins likely enables the nanohaloarchaeal ectosymbiont to utilize exogenous alpha-glucans as carbon sources (as an alternative to exogenous GlcNAc). This (omics-inferred) nanohaloarchaeon capability for extracellular hydrolysis was tested and validated experimentally, and the growth of the LC1Hm+LC1Nh association on starch and glycogen was demonstrated. From these experiments, we conclude that interspecies cross-feeding occurs in the nanohaloarchaeon–Halomicrobium coculture: Ca. Nanohalobium is obligately dependent on Halomicrobium during growth in all conditions, while Halomicrobium benefits from the nanohaloarchaeon during growth on glycogen and starch which would otherwise be inaccessible. The experimental evidence that a DPANN ectosymbiont can increase the vigor of its host is, as far as we know, unprecedented and offers a perspective on the host–ectosymbiont interaction in hypersaline ecosystems. Indeed, under the in situ conditions of natural ecosystems at or approaching salt saturation, such alpha-glucans may be provided by halophilic green algae in the form of alpha-glucans, an extracellular linear (1 → 4)-α-d-glucan polysaccharide (46). Keeping in mind that chitinous arthropods of the genus Artemia are less tolerant to extreme salinities (> 4 M NaCl) than some halophilic green algae such as Dunaliella (5, 6), the association between the nanohaloarchaeon and haloarchaea may benefit the host under salt-saturated conditions when arthropod chitin is less available than algal-derived alpha-glucans. We believe, therefore, that changes that can occur during evapo-concentration cycles can produce temporal oscillations in the availability of different substrates, thereby helping to maintain the symbiotic dependency between nanohaloarchaeon and host.

A recent report (23) on the short-term maintenance (<100 d) of Antarctic nanohaloarchaeon Nha-C (Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus) in a reconstructed coculture with the heterotrophic generalist, haloarchaeon Halorubrum lacusprofundi, shows some parallels with the present work. Like Ca. Nanohalobium, the Antarctic nanohaloarchaea required the presence of a specific haloarchaeon for growth and were not able to propagate when unattached to the host. Although specific trophic and genetic interactions within the Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus–H. lacusprofundi partnership remain to be experimentally proven, our genomic and proteomic data point to the former nanohaloarchaeon as having a similar type of metabolism, deciphered in Ca. Nanohalobium. Apparently, geographically and phylogenetically diverse members of the Ca. Nanohaloarchaeota have evolved specific symbiotic interactions with their hosts and may have recruited distinct systems for recognizing hosts and conferring host specificity. Not surprisingly, considering the relatively large phylogenetic distance (Fig. 1), the levels of syntheny and sequence similarity of Ca. Nanohalobium to Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum and to other nanohaloarchaea are modest. To start with, Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus possesses unusually large SPEARE proteins which are likely involved in attachment to a host. Although homologs of these genes are found in many nanohaloarchaeal genomes, they are absent in Ca. Nanohalobium. Conversely, Ca. Nanohalobium does possess its diversity-generating retroelements locus, which is not seen in other nanohaloarchaeal genomes.

Using all publicly available nanohaloarchaeal MAGs, we predicted the general metabolic hallmarks of diverse members of the Ca. Nanohaloarchaeota (Fig. 6). It is very likely that all of them are aerotolerant heterotrophic anaerobes possessing glycolysis, pyruvate fermentation, gluconeogenesis, and glycogen synthesis/depolymerization as the main pathways of energy gaining and conservation. With only one exception, they all lack the pentose phosphate pathway. Our cultivation experiments indicated the strong magnesium dependence for growth of Ca. Nanohalobium, which seems in agreement with the physiological requirements of Ca. Nanohaloarchaeum antarcticus, maintained in DBSM2 medium (285 mM Mg2+) (23). Nonetheless, there are recent indications of nanohaloarchaea thriving in soda lakes with trace amounts of dissolved Mg2+ (< 1 mM) (47). Another feature common to all nanohaloarchaea with reconstructed genomes is the presence of organism-specific lectin-like proteins containing one or more of the laminin globular- or Con A-like domains. These large proteins possess many N-glycosylation sites and are predicted to be part of a complex, host-specific cell attachment system. These metabolic predictions raise an important question about the evolution of the Nanohaloarchaeota lifestyle and provide the opportunity to study whether the phenomenon of interspecies cross-feeding is common, such as that found between Ca. Nanohalobium and the Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm host.

Fig. 6.

Comparative metabolic analysis of the 19 nanohaloarchaeal genomes thus far sequenced. Proteins of Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh proteins are shown in magenta. The A-type H+ translocating ATPase complex (nine subunits) is intact in 13 nanohaloarchaeal genomes, whereas incomplete complexes are shown in gray with the numbers of subunits found. The list is not mutually exclusive, as a given protein can have more than one function or domain and was counted in each appropriate category.

It is tempting to speculate that the susceptibility of at least some individuals within Halomicrobium populations to colonization by the Ca. Nanohalobium cells might be a kind of survival strategy, resembling a so-called “bet-hedging trait” (48, 49), which would have negligible impact on the host fitness under one condition—in this case, an abundance of chitin—but can increase the host fitness under another condition, i.e., abundance of alpha-glucans (starch and glycogen). The experimental tractability of the host–symbiont system described in the current study may enable future studies to identify ecological determinants of the symbiosis based on, for example, fitness measurements, providing definitive evidence of such mutual interdependence in Archaea.

The current study also reveals a mechanism by which to culture a hitherto uncultured microbe. There is an astonishing diversity and quantity of polysaccharides present in natural ecosystems, so it may be that similar approaches can bring other unculturable taxa into the culture. The findings reported here also give rise to a number of as-yet-unresolved questions. Many types of brine that host microbial life are neither NaCl-dominated nor thalassohaline in origin (50). Given that DPANN archaea have been reported in several chaotropic, MgCl2-dominated deep-sea ecosystems and in magnesium-depleted soda lakes that likely contain various polysaccharides of phyto- and zooplankton origin (22, 38, 51, 52), does metabolic mutualism of a similar kind as reported here also occur in those habitats? We were impressed by the subtlety and complexity of metabolic interactions between Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh and Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm. We have yet to learn whether cells of these partners communicate prior to contact and, upon physical contact, which of these partners takes the first metabolic step to initiate a more-intimate interaction? We noted the apparent host specificity of Ca. Nanohalobium in favor of Halomicrobium (see above). This said, we are left wondering whether an individual nanohaloarchaeon cell can ever detach from its host and, if so, can it go on to attach to that of a different Halomicrobium? We may yet find that this apparently loyal partner is in fact rather promiscuous.

Materials and Methods

Sediment cores (the top 5 cm), composed mainly of salt crystals and brine, were sampled in June 2016 from the final crystallizer pond Vasca #27 of the solar saltern system Saline della Laguna (Sicily, Italy). Chemical analysis of environmental samples, cultivation conditions, microbial community analysis, genome sequencing and assembly, phylogenomic studies, proteome analysis, analysis of polymer hydrolysis metabolites, quantitative PCR, field emission scanning and transmission electron microscopies and fluorescence microscopy are detailed in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Adele Occhipinti for kind permission and assistance with sampling in the solar salterns of Trapani and Alexander Yakunin for useful advice and discussion. This study was partially supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of University and Research under the RITMARE Flagship Project (2012–2016) and the INMARE Project (Contract H2020-BG-2014-2634486), funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research Program. P.N.G. and O.V.G. acknowledge support from the Centre for Environmental Biotechnology Project, partly funded by the European Regional Development Fund via the Welsh Assembly Government. D.Y.S. was supported by SYAM-Gravitation Program of the Dutch Ministry of Education and Science Grant 24002002 and Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grant 19-04-00401). S.V.T. acknowledges Kurchatov Centre for Genome Research, and his work was supported by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russian Federation Grant 075-15-2019-1659.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data depositon: Genomes of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm are available under GenBank BioProject PRJNA565665, BioSample SAMN12757031, accession nos. CP044129 (chromosome) and CP044130 (plasmid) and for Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh, BioProject PRJNA531595, Biosample SAMN11370769, accession no. CP040089. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016346.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2007232117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Genomes for Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm are available under GenBank BioProject PRJNA565665, BioSample SAMN12757031, accession numbers CP044129 (chromosome) and CP044130 (plasmid) and for Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh, BioProject PRJNA531595, Biosample SAMN11370769, accession number CP040089. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (53) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016346, and can be directly accessed using following link: ftp://ftp.pride.ebi.ac.uk/pride/data/archive/2020/07/PXD016346. To make data related to the metabolic potential of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm and Ca. Nanohalobum constans LC1Nh available, we have uploaded their genomes to Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) (54) (https://rast.nmpdr.org/rast.cgi). It is possible to access these data by logging in to RAST using the guest feature (login: guest; password: guest). The ID numbers are 2565781.4, 2610902.4, and 2610902.5.

References

- 1.Lee C. J. D. et al., NaCl-saturated brines are thermodynamically moderate, rather than extreme, microbial habitats. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42, 672–693 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins N. C., Population ecology of Ephydra cinerea Jones (Diptera: Ephydridae), the only benthic metazoan of the Great Salt Lake, U.S.A. Hydrobiologia 68, 99–112 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zmora O., Avital E., Gordin H., Results of an attempt for mass production of Artemia in extensive ponds. Aquaculture 213, 395–400 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litvinenko L. I., Litvinenko A. I., Boiko E. G., Kutsanov K., Artemia cyst production in Russia. Chin. J. Oceanology Limnol. 33, 1436–1450 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korovessis N. A., Lekkas T. D., Solar Saltworks’ wetland function. Glob. NEST J. 11, 49–57 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrei A. Ş., Banciu H. L., Oren A., Living with salt: Metabolic and phylogenetic diversity of archaea inhabiting saline ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 330, 1–9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oren A., Life at High Salt Concentrations (Springer, New York, 2006), vol. 2, chap. 1.9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorokin D. Y. et al., Phenotypic and genomic properties of Chitinispirillum alkaliphilum gen. nov., sp. nov., A haloalkaliphilic anaerobic chitinolytic bacterium representing a novel class in the phylum Fibrobacteres. Front. Microbiol. 7, 407 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou J. et al., Characterization of genes for chitin catabolism in Haloferax mediterranei. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 1185–1194 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorokin D. Y., Toshchakov S. V., Kolganova T. V., Kublanov I. V., Halo(natrono)archaea isolated from hypersaline lakes utilize cellulose and chitin as growth substrates. Front. Microbiol. 6, 942 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorokin D. Y. et al., Natrarchaeobius chitinivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., and Natrarchaeobius halalkaliphilus sp. nov., alkaliphilic, chitin-utilizing haloarchaea from hypersaline alkaline lakes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 42, 309–318 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minegishi H. et al., Salinarchaeum chitinilyticum sp. nov., a chitin-degrading haloarchaeon isolated from commercial salt. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 2274–2278 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinke C. et al., Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature 499, 431–437 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adam P. S., Borrel G., Brochier-Armanet C., Gribaldo S., The growing tree of Archaea: New perspectives on their diversity, evolution and ecology. ISME J. 11, 2407–2425 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castelle C. J. et al., Biosynthetic capacity, metabolic variety and unusual biology in the CPR and DPANN radiations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 629–645 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dombrowski N., Lee J. H., Williams T. A., Offre P., Spang A., Genomic diversity, lifestyles and evolutionary origins of DPANN archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 366, fnz008 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghai R. et al., New abundant microbial groups in aquatic hypersaline environments. Sci. Rep. 1, 135 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narasingarao P. et al., De novo metagenomic assembly reveals abundant novel major lineage of Archaea in hypersaline microbial communities. ISME J. 6, 81–93 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crits-Christoph A. et al., Functional interactions of archaea, bacteria and viruses in a hypersaline endolithic community. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 2064–2077 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrade K. et al., Metagenomic and lipid analyses reveal a diel cycle in a hypersaline microbial ecosystem. ISME J. 9, 2697–2711 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selivanova E. A., Poshvina D. V., Khlopko Y. A., Gogoleva N. E., Plotnikov A. O., Diversity of prokaryotes in planktonic communities of saline Sol-Iletsk lakes (Orenburg Oblast, Russia). Microbiology 87, 569–582 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.La Cono V. et al., The discovery of Lake Hephaestus, the youngest athalassohaline deep-sea formation on Earth. Sci. Rep. 9, 1679 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamm J. N. et al., Unexpected host dependency of Antarctic Nanohaloarchaeota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 14661–14670 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huber H. et al., A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature 417, 63–67 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wurch L. et al., Genomics-informed isolation and characterization of a symbiotic Nanoarchaeota system from a terrestrial geothermal environment. Nat. Commun. 7, 12115 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golyshina O. V. et al., “ARMAN” archaea depend on association with euryarchaeal host in culture and in situ. Nat. Commun. 8, 60 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St John E. et al., A new symbiotic nanoarchaeote (Candidatus Nanoclepta minutus) and its host (Zestosphaera tikiterensis gen. nov., sp. nov.) from a New Zealand hot spring. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 42, 94–106 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvie C. E., Weare J. H., The prediction of mineral solubilities in natural waters: The Na-K-Mg-Ca-Cl-S04-H20 system from zero to high concentrations at 25°C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 44, 98l–997 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvie C. E., Eugster H. P., Weare J. H., Mineral equilibria in the six-component seawater system, Na-K-Mg-Ca-S04-Cl-H2O at 25°C. II: Compositions of the saturated solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 46, 1603–1618 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Lange G. J. et al., Composition of anoxic hypersaline brines in the Tyro and Bannock Basins, Eastern Mediterranean. Mar. Chem. 31, 63–88 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui H.-L., Zhou P. J., Oren A., Liu S. J., Intraspecific polymorphism of 16S rRNA genes in two halophilic archaeal genera, Haloarcula and Halomicrobium. Extremophiles 13, 31–37 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pruesse E. et al., SILVA: A comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 7188–7196 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludwig W. et al., ARB: A software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1363–1371 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yarza P. et al., Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 635–645 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parks D. H. et al., A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 996–1004 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oren A., Elevi R., Watanabe S., Ihara K., Corcelli A., Halomicrobium mukohataei gen. nov., comb. nov., and emended description of Halomicrobium mukohataei. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 1831–1835 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorokin D. Y. et al., Natronobiforma cellulositropha gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel haloalkaliphilic member of the family Natrialbaceae (class Halobacteria) from hypersaline alkaline lakes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 41, 355–362 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamill P. G. et al., Microbial lag phase can be indicative of, or independent from, cellular stress. Sci. Rep. 10, 5948 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tindall B. J. et al., Complete genome sequence of Halomicrobium mukohataei type strain (arg-2). Stand. Genomic Sci. 1, 270–277 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werner J. et al.; MAMBA Consortium , Halorhabdus tiamatea: Proteogenomics and glycosidase activity measurements identify the first cultivated euryarchaeon from a deep-sea anoxic brine lake as potential polysaccharide degrader. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 2525–2537 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E. V., Archaeal clusters of orthologous genes (arCOGs): An update and application for analysis of shared features between Thermococcales, Methanococcales, and Methanobacteriales. Life (Basel) 5, 818–840 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorokin D. Y. et al., Discovery of extremely halophilic, methyl-reducing euryarchaea provides insights into the evolutionary origin of methanogenesis. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17081 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albers S. V., Jarrell K. F., The Archaellum: An update on the unique archaeal motility structure. Trends Microbiol. 26, 351–362 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Coq J., Ghosh P., Conservation of the C-type lectin fold for massive sequence variation in a Treponema diversity-generating retroelement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 14649–14653 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Handa S., Paul B. G., Miller J. F., Valentine D. L., Ghosh P., Conservation of the C-type lectin fold for accommodating massive sequence variation in archaeal diversity-generating retroelements. BMC Struct. Biol. 16, 13 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goo B. G. et al., Characterization of a renewable extracellular polysaccharide from defatted microalgae Dunaliella tertiolecta. Bioresour. Technol. 129, 343–350 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vavourakis C. D. et al., A metagenomics roadmap to the uncultured genome diversity in hypersaline soda lake sediments. Microbiome 6, 168 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simons A. M., Fluctuating natural selection accounts for the evolution of diversification bet hedging. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 1987–1992 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grimbergen A. J., Siebring J., Solopova A., Kuipers O. P., Microbial bet-hedging: The power of being different. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 25, 67–72 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hallsworth J. E., Microbial unknowns at the saline limits for life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1503–1504 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallsworth J. E. et al., Limits of life in MgCl2-containing environments: Chaotropicity defines the window. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 801–813 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yakimov M. M. et al., Microbial community of the deep-sea brine Lake Kryos seawater-brine interface is active below the chaotropicity limit of life as revealed by recovery of mRNA. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 364–382 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez-Riverol Y. et al., The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: Improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D442–D450 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Overbeek R. et al., The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D206–D214 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Genomes for Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm are available under GenBank BioProject PRJNA565665, BioSample SAMN12757031, accession numbers CP044129 (chromosome) and CP044130 (plasmid) and for Ca. Nanohalobium constans LC1Nh, BioProject PRJNA531595, Biosample SAMN11370769, accession number CP040089. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE (53) partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD016346, and can be directly accessed using following link: ftp://ftp.pride.ebi.ac.uk/pride/data/archive/2020/07/PXD016346. To make data related to the metabolic potential of Halomicrobium sp. LC1Hm and Ca. Nanohalobum constans LC1Nh available, we have uploaded their genomes to Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) (54) (https://rast.nmpdr.org/rast.cgi). It is possible to access these data by logging in to RAST using the guest feature (login: guest; password: guest). The ID numbers are 2565781.4, 2610902.4, and 2610902.5.