Abstract

Although salivary gland cancers comprise only ~3–6 % of head and neck cancers, treatment options for patients with advanced-stage disease are limited. Because of their rarity, salivary gland malignancies are understudied compared to other exocrine tissue cancers. The comparative lack of progress in this cancer field is particularly evident when it comes to our incomplete understanding of the key molecular signals that are causal for the development and/or progression of salivary gland cancers. Using a novel conditional transgenic mouse (K5:RANKL), we demonstrate that Receptor Activator of NFkB Ligand (RANKL) targeted to cytokeratin 5-positive basal epithelial cells of the salivary gland causes aggressive tumorigenesis within a short period of RANKL exposure. Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis reveals that RANKL markedly increases the expression levels of numerous gene families involved in cellular proliferation, migration, and intra- and extra-tumoral communication. Importantly, cross-species comparison of the K5:RANKL transcriptomic dataset with The Cancer Genome Atlas cancer signatures reveals the strongest molecular similarity with cancer subtypes of the human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. These studies not only provide a much needed transcriptomic resource to mine for novel molecular targets for therapy and/or diagnosis but validates the K5:RANKL transgenic as a preclinical model to further investigate the in vivo oncogenic role of RANKL signaling in salivary gland tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Mouse, RANKL, salivary gland, tumor, transcriptome, RNA-seq

INTRODUCTION

Representing 3–6% of oropharyngeal cancers1–4, salivary gland cancers are a rare and heterogeneous tumor type with at least 24 histologic subtypes of the malignant tumor class3. Although rare, salivary gland malignancies pose a significant public health concern as patients at advanced-stage have a poor prognosis in terms of their long-term survival. Unlike cancers of related exocrine tissues, prognostic and therapeutic management of salivary gland malignancies has not substantially improved in decades. For advanced tumors, radical surgical resection with subsequent adjuvant post-operative radiotherapy is usually the only treatment option2, 4. Apart from facial disfigurement along with nerve damage that can occur with some surgeries (i.e. parotidectomy), sequelae from radiotherapy—xerostomia (dry mouth), taste loss, muscositis with recurrent oral infections, trismus, radiation caries, osteoradionecrosis, and dysphagia—can significantly reduce a patient’s quality of life5–7. Because of their therapeutic ineffectiveness, current chemotherapeutic protocols are frequently repurposed for palliative rather than curative purposes for those patients with advanced-stage disease2, 8, 9. With limited therapeutic options currently available, the consensus in the field is that significant advancements in this area must come from the development of new targeted therapies10–13. Therefore, new oncogenic drivers and their downstream mediators that initiate and/or promote salivary gland tumorigenesis must be identified to achieve this goal.

A member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily of cytokines, receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL) signals through its receptor, RANK14–16. Although RANKL and RANK interact as transmembrane homotrimers, RANKL can also act on RANK through its cleaved ectodomain17. Engagement of RANKL with its receptor results in recruitment of TNF-receptor associated factors (TRAFs) to the cytoplasmic region of RANK, which triggers induction and/or activation of distinct signaling cascades in a cell-context dependent manner18. Numerous studies have demonstrated that unscheduled activation of the RANKL/RANK signaling axis drives a plethora of clinicopathologies, including cancers; reviewed in19. In the case of the mammary gland, a tubuloacinar exocrine tissue like the salivary gland, aberrant RANKL/RANK signaling underpins proliferative, invasive, migratory, and metastatic colonization properties of tumor cells by regulating a broad array of cellular responses, which include (but are not limited to) the execution of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) program, enlarging the cancer stem cell population, and recruiting infiltrating tumor associated macrophages to the tumor microenvironment to enable neoplastic expansion, invasion, and metastasis19–21.

In the case of human head and neck cancers, aberrant RANKL/RANK signaling has been linked to a number of oropharyngeal subtypes, particularly oral carcinomas22–31. Synthesized and secreted from oral squamous cell carcinomas, RANKL (as a paracrine signal) promotes osteolytic invasion of the mandibular bone29–31, similar as in bone metastasis by other RANKL dependent cancers14, 32–35. Recently, immunohistochemical studies have shown that the expression of RANKL and RANK is significantly higher in human salivary gland carcinomas as compared to adenomas36. Importantly, significant expression of RANKL and RANK was observed in salivary duct carcinomas and mucoepidermoid carcinomas36, the latter are the most common malignancy type of the salivary gland37–41.

Using conventional mouse transgenics, we previously demonstrated that RANKL expression targeted to the salivary gland epithelium results in malignancies with a prevalent mucoepidermoid histopathology42. While these studies provide functional support for a causal role for aberrant RANKL/RANK signaling in salivary gland tumor initiation and progression, the early molecular signals that mediate this tumorigenic response were not addressed. To address this issue, studies described herein used transcriptomic analysis of early neoplastic salivary gland tissues derived from a new bi-transgenic mouse model that enables short-term RANKL expression in cytokeratin 5 (K5)-positive basal epithelial cells following doxycycline administration in the adult.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of the K5:RANKL bigenic

The cytokeratin 5-reverse tetracycline transactivator (K5-rtTA) transgenic mouse was purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME (JAX Mice Stock number: 017519; allele type: Tg(KRT5-rtTA)T2D6Sgkd/J). As described previously43, 44, the K5-rtTA transgenic mouse in the FVB/NJ inbred strain carries the bovine keratin 5 (KRT5) promoter, which drives expression of a nuclear localized rtTA gene. The K5-rtTA transgenic mouse enables the inducible expression of genes in K5 positive basal epithelial cells when administered doxycycline. The generation and characterization of our TetO-RANKL responder transgenic mouse was previously described45. Crossing the K5-rtTA effector transgenic with our TetO-RANKL responder transgenic generated the bigenic K5-rtTA: TetO-RANKL mouse (abbreviated K5:RANKL hereon (Figure 1A)). The K5:RANKL bigenic mouse was designed so that doxycycline in the food and water will induce transgene-derived RANKL expression. To induce RANKL transgene expression in the K5:RANKL bigenic, adult (8–9 week old) mice (and monogenic TetO-RANKL control siblings) were switched to rodent chow containing doxycycline at 200mg/kg (Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ (#53888)) and to water containing 0.2% doxycycline (Takara BIO Inc., Mountain View, CA (#631311)) supplied in light protected bottles45–47. To reduce taste aversion, doxycycline fortified water was supplemented with 5% sucrose; doxycycline-supplemented water was changed every 3 days to maintain induction potency.

FIGURE 1 │.

Generation and characterization of the K5:RANKL bigenic mouse. (A) Breeding scheme to generate the K5:RANKL bigenic; the K5-rtTA and TetO-RANKL transgenic mice have been described43–45. (B) Quantitative real time PCR analysis shows that Rankl (Tnfsf11) mRNA levels are significantly increased in salivary gland tissue of adult K5:RANKL mice administered doxycycline for 5-days as compared to similarly treated monogenic control siblings (RNA pooled from five mice per genotype and analysis performed in triplicate). (C) Western immunoblot analysis confirms significant induction of RANKL protein in the salivary glands of K5:RANKL mice that were treated with doxycycline for 5-days; β-actin serves as a loading control. Each lane (lanes 1–3) represents salivary gland protein isolate pooled from three mice per genotype (nine mice total per genotype). (D) Top panels: dual immunofluorescence for K5 and RANKL spatial expression in K5:RANKL salivary gland tissue demonstrates coincident expression of both proteins. Left bottom panel shows immunofluorescence detection of RANKL expression in basal epithelial cells of an interlobular salivary gland duct (white arrowhead). Right bottom panel shows immunohistochemical detection of RANKL expression in basal epithelial cells in ductal and mucinous acini of the K5:RANKL salivary gland (gray and white arrowheads respectively); black arrowhead points to abnormal accumulation of RANKL positive basal epithelial cells. Scale bars denote 10μm.

Mice used in these experiments were housed and maintained in an AAALAC accredited vivarium at Baylor College of Medicine. In temperature-controlled mouse rooms (22 ± 2°C) with a 12-hour lights-on:12-hour lights-off photocycle, mice were fed irradiated Tekland global soy protein-free extruded rodent diet (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN) with free access to fresh water. Experiments on mice were performed according to guidelines detailed in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (“The Guide” (Eighth Edition 2011)), published by the National Research Council of the National Academies, Washington, D.C. (www.nap.edu). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Baylor College of Medicine prospectively approved all animal procedures used in this study.

Histological analysis

Fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, salivary gland normal (monogenic control) and K5:RANKL tumor tissue were processed for embedding in paraffin as reported42. Sections (5μm) of salivary gland tissue and tumor were placed on Superfrost Plus glass slides (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for immunohistochemical staining. Prior to staining, tissue sections were sequentially deparaffinized, rehydrated, and treated with an antigen unmasking solution42. After a blocking step, tissue and tumor sections were incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight. Primary antibodies used in these studies were: a rabbit polyclonal to human cytokeratin 5 (ab53121; Abcam Inc. (1:200), Cambridge, MA); a guinea pig polyclonal to bovine cytokeratin 8+18 (ab194130 (1:200); Abcam Inc.); a sheep polyclonal to 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (ab1893 (1:100); Abcam Inc.); a goat polyclonal anti-mouse RANKL (TRANCE; AF462 (1:200); R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); a rabbit polyclonal anti-human parathyroid hormone related peptide (PTHRP/PTHLH (parathyroid hormone like hormone); LS-B2325 (1:100); LifeSpan BioSciences Inc., Seattle, WA); a rabbit polyclonal anti-human secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1 (osteopontin); ab8448; Abcam Inc.); and a goat polyclonal anti-mouse periostin (POSTN; AF2955 (1:100); R&D Systems). Following incubation with primary antibody, sections were incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (Vector laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with the R.T.U Vectastain Universal ABC reagent (Vector laboratories Inc.) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Immunopositivity was visualized in situ through incubation with 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Vector laboratories Inc.); slides were lightly stained with hematoxylin for contrast. Following a stepwise dehydration process, slides with stained sections were mounted with coverslips using permount solution (Fisher Scientific Inc. (SP15–500)).

For BrdU immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence detection, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (10mg/ml; Amersham Biosciences Corporation, Piscataway, NJ) at a dose of 1mg BrdU/20g body weight two hours prior to euthanasia. For immunofluorescence detection, the following Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibody combinations were used: Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (A-11034) and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-guinea pig IgG (A-11076) were used to detect K5 and K8+K18 respectively. Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (A-11055) and Alexa Fluor 546 donkey anti-sheep IgG (A-11016) were used to detect RANKL and BrdU respectively. Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific Inc. Stained slides were mounted with coverslips using Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA (H-1200)). Digital images of immunostained salivary gland tissue and tumor sections were captured using a color chilled AxioCam MRc5 digital camera attached to a Carl Zeiss AxioImager A1 upright microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). For data display purposes, captured images were digitally collated and annotated with Photoshop and Illustrator (version 6) software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from salivary gland tissue and tumors using TRIzol reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.) before further purification with the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Germantown Road, MD). Purified RNA was reversed transcribed into cDNA using the Superscript IV VILO Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.) before quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) amplification with the Applied Biosystems Step One Plus Real Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.). Detailed information concerning the TaqMan gene expression assays used in these experiments is described in Table 1; 18S ribosomal RNA served as the internal control.

Table 1 │.

List of murine Taqman expression assays used in these studies.

| Gene | ID | Catalog number | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqp5 | 11830 | Mm00437578_m1 | |

| Amy1 | 11722 | Mm00651524_m1 | |

| Ccl8 | 20307 | Mm01297183_m1 | |

| Ccl9 | 20308 | Mm00441260_m1 | |

| Ccr1 | 12768 | Mm00438260_s1 | |

| Cldn22 | 75677 | Mm04209227_sH | |

| Clec4n | 56620 | Mm00490934_m1 | |

| Ctsk | 13088 | Mm00484039_m1 | |

| Cxcl11 | 56066 | Mm00444662_m1 | |

| Dcpp1 | 13184 | Mm03019597_gH | |

| Elf5 | 13711 | Mm00468732_m1 | |

| Esp8 | 100126778 | Mm04243104_m1 | |

| Esp18 | 100126774 | Mm04279607_m1 | |

| Fscn1 | 14086 | Mm00456046_m1 | |

| Krt17 | 1667 | Mm00495207_m1 | |

| Mmp12 | 17381 | Mm00500554_m1 | |

| Muc19 | 239611 | Mm01306462_m1 | |

| Nfkb2 | 18034 | Mm00479807_m1 | |

| Postn | 50706 | Mm01284919_m1 | |

| Prom2 | 192212 | Mm00617472_m1 | |

| Pthrp/Pthlh | 19227 | Mm00436057_m1 | |

| Relb | 19698 | Mm00485664_m1 | |

| Relt | 320100 | Mm00723872_m1 | |

| Scgb2b26 | 110187 | Mm01254729_m1 | |

| Smr3a | 20599 | Mm01964237_s1 | |

| Sox8 | 20681 | Mm00803422_m1 | |

| Spp1 | 20750 | Mm00436767_m1 | |

| Tfec | 22797 | Mm01161234_m1 | |

| Tnfaip2 | 21928 | Mm00447578_m1 | |

| Tnfaip3 | 21929 | Mm00437121_m1 | |

| Tnfrsf4 | 22163 | Mm00442039_m1 | |

| Tnfrsf8 | 21936 | Mm00437140_m1 | |

| Tnfrsf1b | 21938 | Mm00441889_m1 | |

| Tnfrsf11 (Rankl) | 21943 | Mm00441906_m1 | |

| Tnfrsf11a (Rank) | 21934 | Mm00437132_m1 | |

| Traf1 | 22029 | Mm00493827_m1 | |

| 18S rRNA | Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.: 4352930E | ||

Transcriptomic profiling

As with our previous RNA-seq studies48, RNA purity was evaluated with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.) and RNA integrity determined using a 2100 Bioanalyzer with RNA chips (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Only RNA preparations that scored a RNA integrity number (RIN) above 8 were used for RNA-seq. Libraries for mRNA sequencing were prepared with the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) from 250 ng of RNA. Quality analysis of libraries was performed using Agilent 4200 TapeStation with D1000 ScreenTape assays (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were pooled and then quantified by two methods: 1) on a 2100 Bioanalyzer with DNA chips using High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies); and 2) with KAPA Library Quantification Kit for Illumina platforms (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA). Sequencing of mRNA libraries was performed on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform at mid-output of paired-ended 75 base pair sequencing reads.

Analysis of sequenced mRNA

For initial analysis, pair-ended reads were aligned to the mouse genome (UCSC mm10) using open source STAR software49 with NCBI RefSeq genes as the reference; gene expression was measured in read counts for each gene. The R package DESeq250 was used to analyze the gene-based read counts to detect differentially expressed genes between monogenic control and K5:RANKL groups. The false discovery rate (FDR) of differentially expressed genes was estimated using the Benjamini and Hochberg method51; a FDR <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the large number of differentially expressed genes with a FDR <0.05, a cut-off in absolute fold change |FC| >5 and a sum of average counts of control and mutant sample >100 was used for subsequent analysis. Raw mRNA sequencing data were deposited in NCBI/GEO with the super series accession code: GSE121954. Data were analyzed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) version 6.8 Functional Annotation clustering tool and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Maps tool (http://david.ncifcrf.gov). For Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA; (http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp)); mouse entrez gene identification numbers were matched to human homologs using their HomoloGene IDs.

Cross species analysis using the cancer genome atlas

For cross-species comparison analysis, mouse sequencing reads were first adaptor trimmed using TrimGalore software52. Trimmed reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome using the HISAT spliced alignment program53; transcript assembly and quantification were performed using StringTie software53 against the Gencode gene model54. Gene expression (FPKM) was quantile normalized using R statistical software. Differentially expressed genes between K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor and corresponding control samples were determined using the parametric t-test with a p-value <1.25. To compare differentially expressed genes in the K5:RANKL tumor dataset with multiple human cancers profiled by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), GSEA was applied to both up- and down-regulated genes in the K5:RANKL tumor dataset against rank files from multiple cohorts of TCGA human cancers. Results were ranked using a similarity score rewarding matching direction for normalized enriched scores for up- and down-regulated genes55. Normalized enrichment scores (NES) for TCGA human cancer gene signatures and for our K5:RANKL tumor dataset were displayed in a circular combined format using Circos software (http://circos.ca/)56.

Western immunoblot analysis

Protein was isolated from salivary gland tissue and tumors and Western immunoblotting was conducted as previously reported47. Before transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), protein (20 μg) was separated by electrophoresis on a 4–15% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. The following primary antibodies (at 1:1000 dilution) were used: goat polyclonal anti-mouse RANKL (AF462; R&D Systems) and a mouse monoclonal anti-human β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; A1978). After incubation with the appropriate secondary antibody, immunopositive bands were visualized using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate kit (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.). To enable re-probing of the same membrane with different antibodies, membranes were stripped of primary and secondary antibodies using Restore Western Blot Stripping buffer ((#21059) ThermoFisher Scientific Inc.).

Statistical evaluation

As required, data are displayed as means ± standard deviation. The significance of the difference between groups was determined by two-tailed Student’s t tests and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple range tests using the GraphPad and Instat statistical analysis tools (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Unless indicated otherwise, at least three independent replicates were used, and no samples were excluded from any study. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant; asterisks in histograms denote the level of significance: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; and ***p<0.001.

RESULTS

Short-term Doxycycline Administration Induces RANKL Expression in Basal Epithelial Cells of the K5:RANKL Salivary Gland

For transcriptomic profiling described in these studies, the K5:RANKL bigenic mouse (Figure 1A) was used to enable short-term induction of transgene-derived RANKL expression by doxycycline in a specific cell-type of the salivary gland (the K5 positive abluminal basal epithelial cell) at a predetermined age (9-weeks) and for a defined period of time (2-weeks). The above approach was feasible because: (a) RANK is ubiquitously expressed at low levels in the epithelial compartment of the mouse salivary gland42; and (b) the TetO-RANKL effector transgene has proven highly efficient in targeting RANKL expression specifically in response to doxycycline administration45. With just 5-days of doxycycline administration, RANKL was significantly induced at the RNA and protein level in salivary gland tissue of adult K5:RANKL mice (Figure 1B, C); similarly treated monogenic TetO-RANKL control mice did not exhibit this induction (Figure 1B, C). As expected, K5:RANKL mice without doxycycline in the food and water did not exhibit RANKL induction (data not shown). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that doxycycline-induced RANKL expression occurred in the K5 positive basal epithelial cell-type throughout the salivary gland (Figure 1d). Before this immunohistochemical analysis, we confirmed that dual immunofluorescence detection of K5 and K8+18 clearly defines the abluminal basal and luminal epithelial cellular compartments respectively of the normal salivary gland duct (Supplementary Figure 1).

The K5:RANKL Salivary Gland Tumor Exhibits a Predominant Mucoepidermoid Histopathology in Response to Short-Term RANKL Exposure

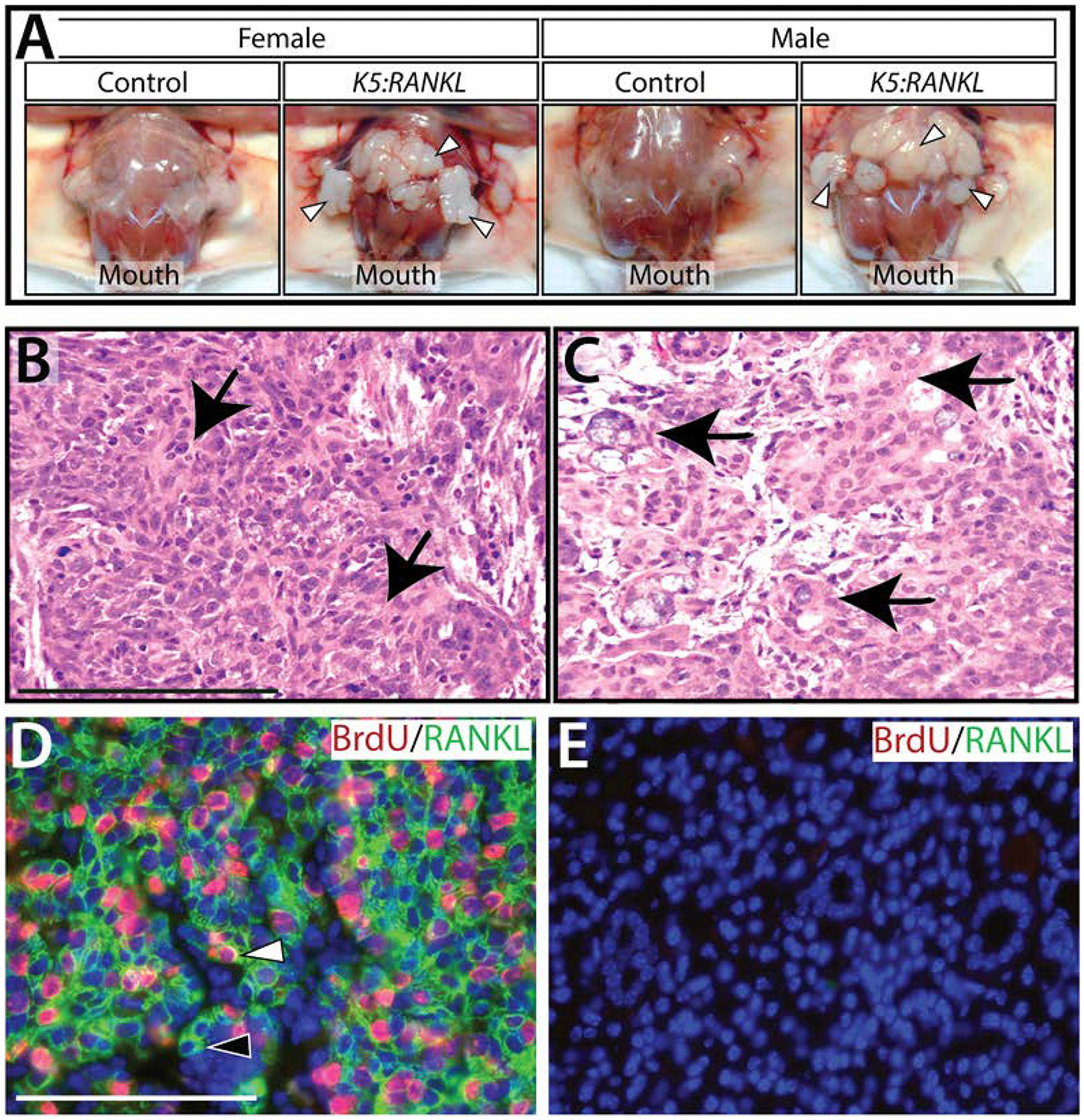

By two weeks of doxycycline administration, both female and male adult K5:RANKL transgenic mice exhibit a swollen neck region that is texturally hard and irregular by palpation (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 2). The salivary gland phenotype was 100% penetrant (n= 30 K5:RANKL females and n= 20 K5:RANKL males (compared with an equal number of similarly treated control mice)) and occurred in the three major salivary glands in the majority of K5:RANKL mice examined. Similar to our recent report42, the histopathology of both female and male K5:RANKL salivary gland neoplasms following 2-weeks of doxycycline administration was consistent with a high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma with sparsely distributed mucinous cells and more frequently occurring epidermoid (squamoid) cells with pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm along with nondescript intermediate cells in varied proportions (Figure 2B,C and Supplementary Figure 3). Dual immunofluorescence detection of RANKL expression and BrdU incorporation revealed that tumor areas in the K5:RANKL salivary gland are highly proliferative and heterogeneous in terms of tumor cells that are double immunopositive for RANKL and BrdU or immunopositive for RANKL alone. However, approximately 35% of tumor cells are double positive for RANKL and BrdU, indicating a possible autocrine and/or paracrine signaling mode for RANKL action in this tumor tissue42. Not surprisingly, transgene-derived RANKL expression was detected in K5 positive basal cells in tissues other than the salivary gland (i.e. mammary gland, thymus, and skin (data not shown)). However, because of the short-term administration of doxycycline, the effects of transgene-derived RANKL expression in K5 positive basal cell types in other epithelial tissues was minimal with only marginal increased branching morphogenesis in the female mammary gland and a slight enlargement of the thymus in both sexes (data not shown).

FIGURE 2 │.

Early morphological and neoplastic cellular changes in the K5:RANKL salivary gland with short-term RANKL expression. (A) Following two weeks of doxycycline administration, female and male K5:RANKL mice show clear evidence of gross morphological changes in their salivary glands (white arrowheads). Compared to controls, the K5:RANKL salivary gland neoplasms are significantly enlarged and ill-defined with a firm consistency. (B) Section stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) from salivary gland neoplastic tissue of a K5:RANKL transgenic mouse shows evidence of squamous differentiation (arrows). (C) Focal glandular differentiation with areas of intracellular mucous is evident (arrows). (D) Dual immunofluorescence detection of BrdU (red) and RANKL (green) in a salivary gland tumor tissue section from a doxycycline-treated K5:RANKL mouse. Note the presence of tumor cells positive for RANKL and BrdU (white arrowhead) as well as tumor cells positive for RANKL alone (black arrowhead). (E) Dual immunofluorescence detection of BrdU and RANKL in salivary gland tissue derived from a similarly treated control mouse. Note the absence of immunopositivity for BrdU and RANKL in the tissue section. Scale bar (100μm) in (B) applies to (C); scale bar (100μm) in (D) applies to (E).

Transcriptional Reprogramming by RANKL Drives Salivary Gland Tumorigenesis

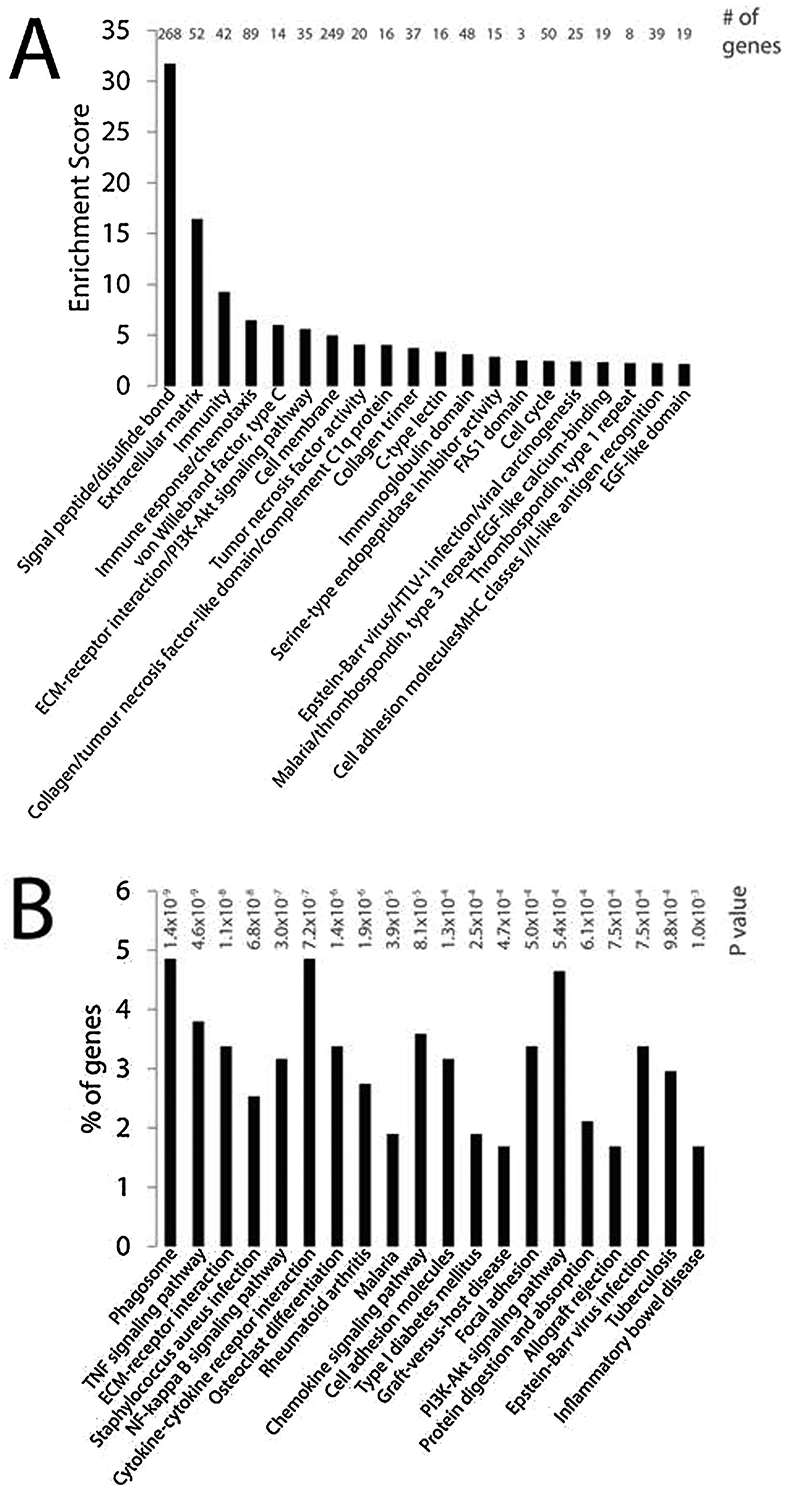

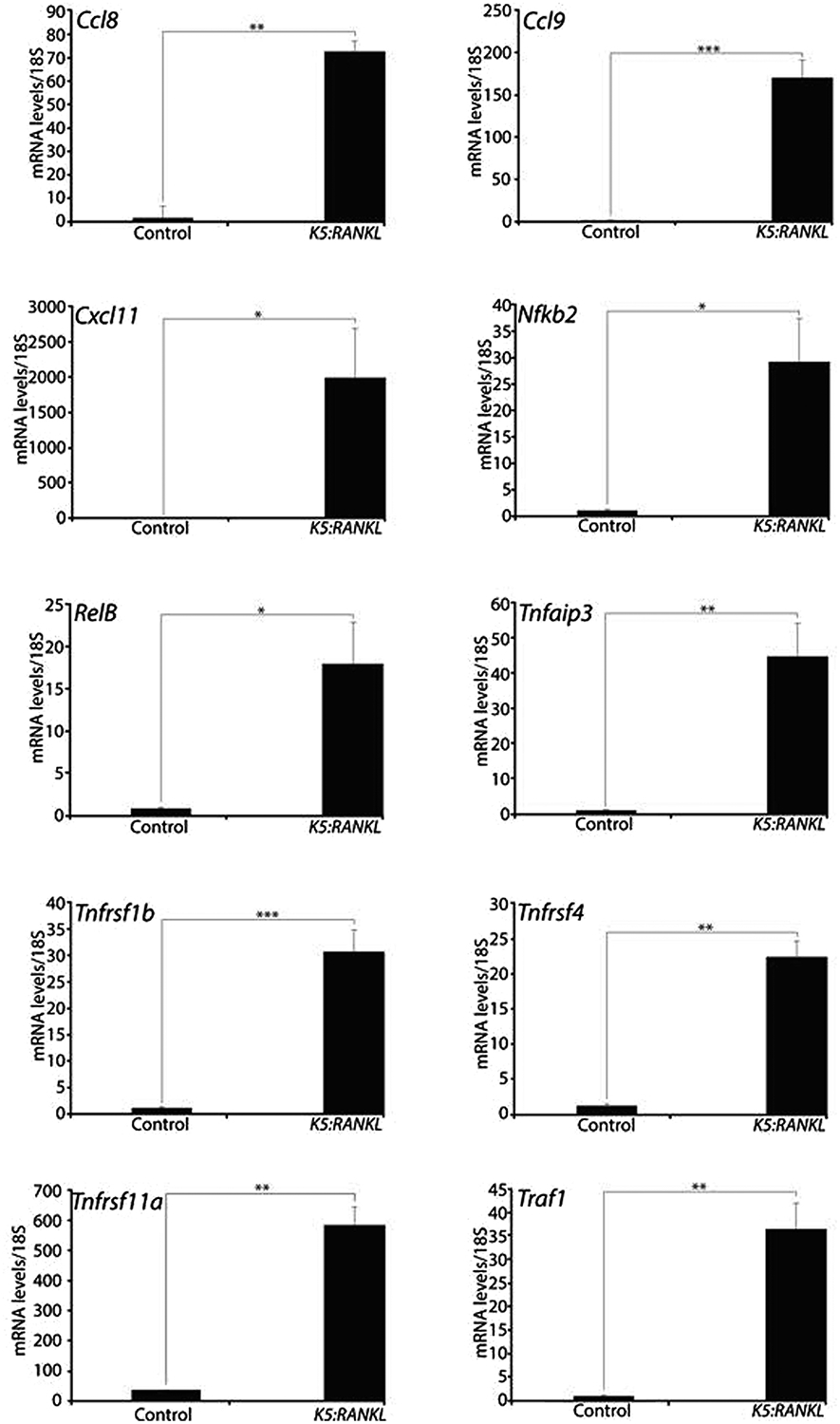

To identify downstream contributory signals that may underpin early neoplastic cellular changes in the K5:RANKL salivary gland, mRNA-seq analysis was performed using salivary gland tissue derived from K5:RANKL female mice and corresponding monogenic controls, which were administered doxycycline at 9-weeks of age for two weeks. Triplicate mRNA samples from K5:RANKL and control groups (n= 5 mice per replicate; 15 mice total per genotype) were sequenced at an average of 20 million read-pairs per sample. Using a FDR <0.05 and a |FC| >5 (and sum of control and K5:RANKL counts >100), a total of 471 genes (375 up-regulated and 96 down-regulated) were differentially expressed between the K5:RANKL and control groups (Supplementary File 1); Table 2 and 3 display the top 50 genes up- and down-regulated respectively. This degree of stringency was chosen to enable subsequent gene enrichment analysis. Differentially expressed genes analyzed with DAVID for functional enrichment and for enrichment in biological pathways cataloged in KEGG respectively revealed a significant representation in genes involved in signal peptide/disulfide bond, extracellular matrix (EM)-receptor interactions, immune response/chemotaxis, tumor necrosis factor signaling, NF-kB signaling, and osteoclast differentiation (Figure 3 and Supplementary File 1). Collectively, these genes serve critical functions in neoplastic development and progression, including cellular proliferation, survival, promotion of EMT, migration, invasion into the tumor microenvironment, and metastasis. Validation at the transcript level of a selection of these differentially expressed genes is shown (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 4). In keeping with the established mediator role for RANKL18, 19, members of the NF-kB signaling cascade are significantly represented in the K5:RANKL tumor signature as well as pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine family members (Figure 3, 4). Not surprisingly, many genes (i.e. amylase 1 (Amy1) and aquaporin 5 (Aqp5)) involved in normal salivary gland function are significantly down-regulated in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor compared to normal salivary gland tissue (Supplementary Figure 4). Although salivary gland excrinopathy is predicted by the down-regulation in the expression of these genes, the K5:RANKL mice did not exhibit overt signs of salivary gland dysfunction (i.e. absence or reduced saliva).

Table 2 │.

Top 50 genes upregulated in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor.

| GENE | GENE ID | GENE NAME | K5:RANKL/CONTROL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ccl20 | 20297 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 | 577.6 |

| Alox12e | 11685 | arachidonate lipoxygenase, epidermal | 468.7 |

| Abca13 | 268379 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 13 | 269.7 |

| Dsg1a | 13510 | desmoglein 1 alpha | 215.4 |

| Msln | 56047 | mesothelin | 176.0 |

| Gm8909 | 667977 | predicted gene 8909 | 152.5 |

| Hal | 15109 | histidine ammonia lyase | 144.4 |

| Tnfsf11 | 21943 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11 | 127.7 |

| Eno1b | 433182 | enolase 1B, retrotransposed | 126.0 |

| Calcb | 116903 | calcitonin-related polypeptide, beta | 116.7 |

| Irg1 | 16365 | immunoresponsive gene 1 | 113.2 |

| Fcgbp | 215384 | Fc fragment of IgG binding protein | 90.8 |

| Plb1 | 665270 | phospholipase B1 | 87.9 |

| H2-Ea-ps | 100504404 | histocompatibility 2, class II antigen E alpha, pseudogene | 86.5 |

| Slc30a2 | 230810 | solute carrier family 30 (zinc transporter), member 2 | 84.2 |

| Alox15 | 11687 | arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase | 83.7 |

| Spp1 | 20750 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | 79.6 |

| Serpina3h | 546546 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 3H | 78.3 |

| Gad1 | 14415 | glutamate decarboxylase 1 | 72.4 |

| Spink5 | 72432 | serine peptidase inhibitor, Kazal type 5 | 65.2 |

| Dsg1b | 225256 | desmoglein 1 beta | 64.0 |

| Thbs4 | 21828 | thrombospondin 4 | 60.3 |

| Plekhs1 | 226245 | pleckstrin homology domain containing, family S member 1 | 60.2 |

| Sox8 | 20681 | SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 8 | 60.2 |

| Mmp12 | 17381 | matrix metallopeptidase 12 | 59.6 |

| Cd207 | 246278 | CD207 antigen | 59.5 |

| Mmp9 | 17395 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | 59.5 |

| H2-Q1 | 15006 | histocompatibility 2, Q region locus 1 | 57.6 |

| Sectm1a | 209588 | secreted and transmembrane 1A | 57.0 |

| Serpina3n | 20716 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 3N | 54.3 |

| Gdpd3 | 68616 | glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase domain containing 3 | 53.4 |

| Tnfrsf11b | 18383 | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 11b (osteoprotegerin) | 52.0 |

| Fcamr | 64435 | Fc receptor, IgA, IgM, high affinity | 52.0 |

| Adamts13 | 279028 | a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase (reprolysin type) with thrombospond | 48.9 |

| Foxn1 | 15218 | forkhead box N1 | 48.1 |

| Wnt7b | 22422 | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 7B | 47.6 |

| Tnfaip2 | 21928 | tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 2 | 46.4 |

| Cxcl11 | 56066 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | 46.3 |

| Gm1821 | 218963 | ubiquitin pseudogene | 46.3 |

| Serpina3i | 628900 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 3I | 44.8 |

| Col8a1 | 12837 | collagen, type VIII, alpha 1 | 44.1 |

| Cyp2a5 | 13087 | cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily a, polypeptide 5 | 40.3 |

| Aadac | 67758 | arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) | 39.5 |

| Ctsk | 13038 | cathepsin K | 39.1 |

| Ccl9 | 20308 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | 37.0 |

| S100a14 | 66166 | S100 calcium binding protein A14 | 34.9 |

| Gm8615 | 667410 | glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase 1 pseudogene | 34.7 |

| Ccnb1ip1 | 239083 | cyclin B1 interacting protein 1 | 33.1 |

| C920025E04Rik | 667803 | RIKEN cDNA C920025E04 gene | 32.9 |

| Spib | 272382 | Spi-B transcription factor (Spi-1/PU.1 related) | 32.2 |

Table 3 │.

Top 50 genes downregulated in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor.

| GENE | GENE ID | GENE NAME | K5:RANKL/CONTROL |

|---|---|---|---|

| BC018473 | 193217 | cDNA sequence BC018473 | −564.7 |

| Dcpp3 | 620253 | demilune cell and parotid protein 3 | −89.6 |

| Pgr | 18667 | progesterone receptor | −74.1 |

| Hapln4 | 330790 | hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 4 | −62.2 |

| Cldn22 | 75677 | claudin 22 | −49.5 |

| Crisp1 | 11571 | cysteine-rich secretory protein 1 | −43.1 |

| Bpifa2 | 19194 | BPI fold containing family A, member 2 | −42.2 |

| Nxpe4 | 244853 | neurexophilin and PC-esterase domain family, member 4 | −41.6 |

| Smr3a | 20599 | submaxillary gland androgen regulated protein 3A | −41.0 |

| Prb1 | 381833 | proline-rich protein BstNI subfamily 1 | −33.8 |

| Dnase1 | 13419 | deoxyribonuclease I | −31.1 |

| Azgp1 | 12007 | alpha-2-glycoprotein 1, zinc | −28.3 |

| St6galnac1 | 20445 | ST6 (alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminyl-2,3-beta-galactosyl-1,3)-N-acetylgalactosam | −26.3 |

| Prpmp5 | 381832 | proline-rich protein MP5 | −24.2 |

| Ggh | 14590 | gamma-glutamyl hydrolase | −22.9 |

| 2610507I01Rik | 72203 | RIKEN cDNA 2610507I01 gene | −19.4 |

| Amy1 | 11722 | amylase 1, salivary | −19.1 |

| Rab6b | 270192 | RAB6B, member RAS oncogene family | −18.9 |

| Esp18 | 100126774 | exocrine gland secreted peptide 18 | −18.3 |

| 1700066N21Rik | 73471 | RIKEN cDNA 1700066N21 gene | −18.3 |

| Shisa7 | 232813 | shisa family member 7 | −16.1 |

| Ret | 19713 | ret proto-oncogene | −14.7 |

| Lipo1 | 381236 | lipase, member O1 | −14.2 |

| Gm4736 | 114600 | predicted gene 4736 | −13.7 |

| H2-Eb1 | 14969 | histocompatibility 2, class II antigen E beta | −12.5 |

| Mup6 | 620807 | major urinary protein 6 | −11.8 |

| Ttr | 22139 | transthyretin | −11.5 |

| Gprc6a | 210198 | G protein-coupled receptor, family C, group 6, member A | −11.0 |

| Fgf1 | 14164 | fibroblast growth factor 1 | −10.9 |

| Cst10 | 58214 | cystatin 10 (chondrocytes) | −10.3 |

| Chia1 | 81600 | chitinase, acidic 1 | −10.0 |

| Agt | 11606 | angiotensinogen (serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 8) | −10.0 |

| B4galnt3 | 330406 | beta-1,4-N-acetyl-galactosaminyl transferase 3 | −9.7 |

| Rbm20 | 73713 | RNA binding motif protein 20 | −9.6 |

| 9130230L23Rik | 231253 | RIKEN cDNA 9130230L23 gene | −9.6 |

| Tcea3 | 21401 | transcription elongation factor A (SII), 3 | −9.2 |

| AI463170 | 100504549 | expressed sequence AI463170 | −8.9 |

| Isoc2b | 67441 | isochorismatase domain containing 2b | −8.7 |

| Unc5a | 107448 | unc-5 netrin receptor A | −8.5 |

| Atp6v1c2 | 68775 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit C2 | −8.4 |

| Ttc25 | 74407 | tetratricopeptide repeat domain 25 | −8.4 |

| 2310057J18Rik | 67719 | RIKEN cDNA 2310057J18 gene | −8.3 |

| Esp8 | 100126778 | exocrine gland secreted peptide 8 | −8.2 |

| 4833423E24Rik | 228151 | RIKEN cDNA 4833423E24 gene | −8.2 |

| Insig1 | 231070 | insulin induced gene 1 | −8.0 |

| Rap1gap | 110351 | Rap1 GTPase-activating protein | −7.9 |

| Muc19 | 239611 | mucin 19 | −7.9 |

| Aldh3b2 | 621603 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 3 family, member B2 | −7.8 |

| Scgb2b26 | 110187 | secretoglobin, family 2B, member 26 | −7.8 |

| Gpr37l1 | 171469 | G protein-coupled receptor 37-like 1 | −7.7 |

FIGURE 3 │.

Differentially expressed genes between K5:RANKL salivary gland tumors and control salivary gland tissue analyzed by DAVID. (A) DAVID functional annotation clustering analysis for enrichment of differentially expressed genes in functionally-related gene groups/gene ontology terms. The enrichment score is based on the EASA score of each term. (B) DAVID KEGG pathway analysis of biological/signaling pathways enriched in the differentially expressed gene dataset between K5:RANKL and control salivary gland group.

FIGURE 4 │.

Genes involved in chemokine, NFkB, and TNF signaling are significantly expressed in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor. Quantitative real-time PCR demonstrates that members of the chemokine/chemokine receptor (i.e. chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 (Ccl8); chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 (Ccl9); C-C chemokine receptor type 1 (Ccr1); and C-X-C motif chemokine 11 (Cxcl11)); NFkB (i.e. nuclear factor kappa B subunit 2 (Nfkb2); and RelB proto-oncogene, Nfkb subunit (RelB)); and TNF (i.e. TNF alpha induced protein 3 (Tnfaip3); TNF receptor superfamily member 1B (Tnfrsf1b); TNF receptor superfamily member 4 (Tnfrsf4); TNF receptor superfamily member 11a (Tnfrsf11a (Rank)); and TNF receptor associated factor 1 (Traf1)) signaling pathways are highly expressed in K5:RANKL salivary gland tumors. Data are represented as the average expression fold change relative to control group ± standard deviation (n=4 mice per control and K5:RANKL groups).

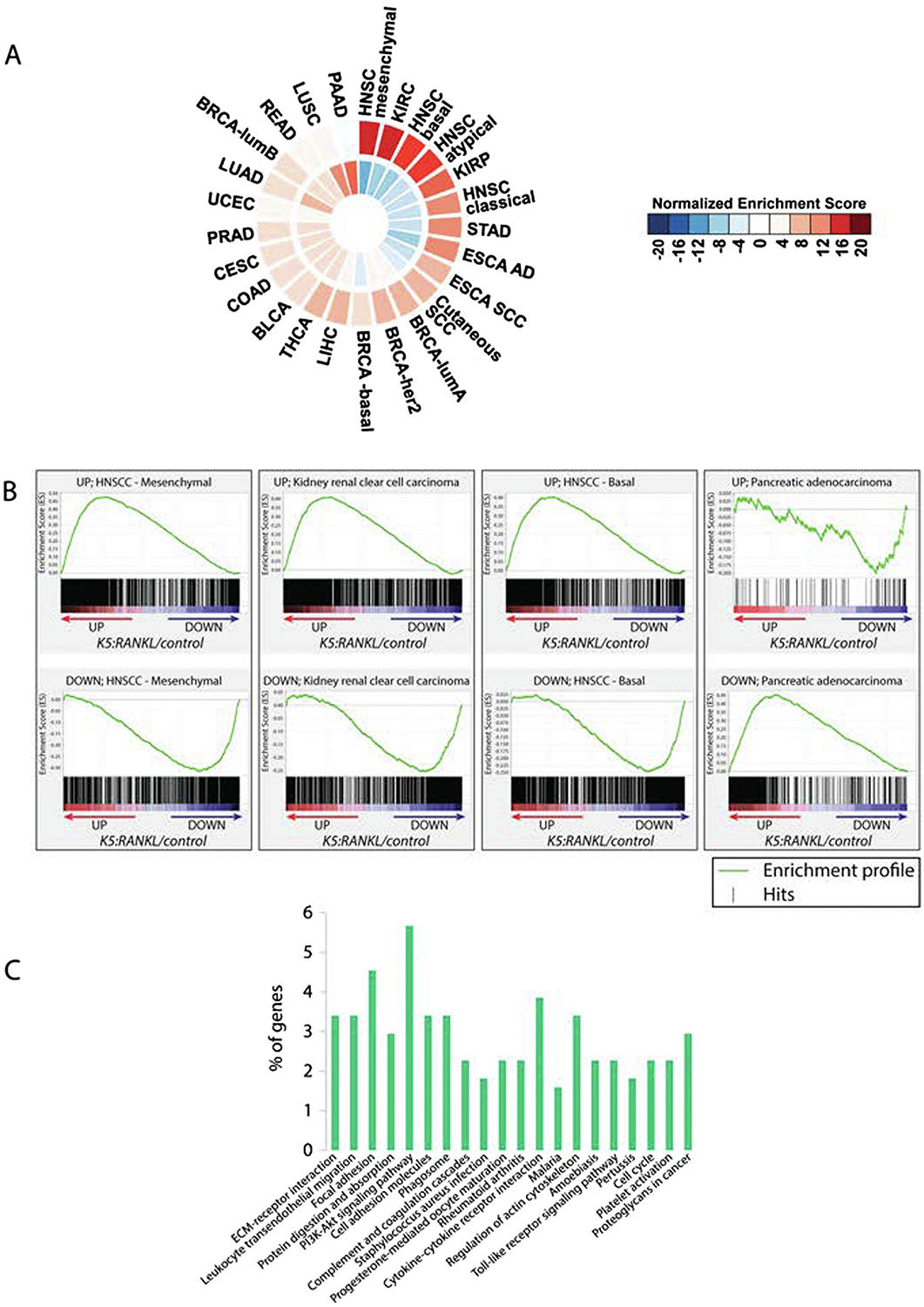

The K5:RANKL Salivary Gland Tumor is Most Closely Related to Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Subtypes

To determine the translational significance of our molecular findings in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor, we assessed the degree of molecular similarity between our K5:RANKL tumor transcriptomic dataset with transcriptomic signatures of 25 human cancers profiled in the TCGA. Combined NES for all TCGA tumor development gene signatures and our K5:RANKL tumor dataset were visualized using Circos software (Figure 5A56). Of the 25 human cancers analyzed, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) subtypes were listed within the top four cancers—HNSC (mesenchymal subtype); kidney renal clear-cell carcinoma (KIRC); HNSC (basal); and HNSC (atypical)—that scored the closest molecular similarity to the K5:RANKL tumor transcriptomic signature (Figure 5A,B). Many of the pathways enriched between the HNSC (mesenchymal) and our K5:RANKL tumor dataset are associated with tumor cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis (Figure 5C and Supplemental File 2). All gene expression changes, which were selected from this gene list (Supplementary File 2), validated at the transcriptional level (Figure 6). Using PTHRP, SPP1 and POSTN as examples from this gene list (Supplementary File 2), our immunohistochemical analysis confirmed significant expression of these three genes at the protein level in K5:RANKL salivary gland tumors as compared with control salivary gland tissue (Figure 7).

FIGURE 5 │.

The molecular signature of the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor most closely resembles human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma subtypes. (A) Normalized enrichment scores for each of the 25 human cancer signatures compared to corresponding K5:RANKL/control were calculated. Cancer types were ranked by similarity to the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor signature in descending order and in a clockwise direction on a Circos Plot. The outside ring displays enrichment of up-regulated transcripts while the inside ring shows the enrichment of down-regulated transcripts. Circular presentation of the data clearly shows that the K5:RANKL signature is most closely related to mesenchymal and basal subtypes of the head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Note: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma–mesenchymal subtype (HNSC-mesenchymal); kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC); kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP); stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD); esophageal adenocarcinoma (ESCA AD); esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCA SCC); cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); breast cancer luminal A (lum A) subtype; breast cancer her2 subtype; breast cancer basal subtype; liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC); thyroid carcinoma (THCA); bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA); colon adenocarcinoma (COAD); cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC); prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD); uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC); lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD); breast cancer luminal B subtype (BRCA-lumB); rectum adenocarcinoma (READ); lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC); and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD). (B) Enrichment plots of the TCGA tumor datasets that most positively and inversely correlated with the K5:RANKL gene expression signature. (C) Pathway analysis by DAVID KEGG pathway tool of genes shared between the HNSCC GSEA datasets and the mouse K5: RANKL signature.

FIGURE 6 │.

Validation of gene expression changes in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor that are also changed in human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Quantitative real time PCR results show significant expression changes of genes (i.e. C-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (Ccr1); Claudin 22 (Cldn22); C-type lectin domain family 4, member n (Clec4n); Cathepsin K (Ctsk); Fascin 1 (Fscn1); Keratin 17 (Krt 17); Periostin (Postn); Parathyroid hormone related peptide (Pthrp); Receptor expressed in lymphoid tissue (Relt); Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1); Transcription factor EC (Tfec); and Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 8 (Tnfrsf8)) in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor that are also markedly changed in expression levels in human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (Supplementary File 2). Data are represented as standard deviation of the average fold change (n=4 mice per control and K5:RANKL groups).

FIGURE 7 │.

The K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor expresses high levels of PTHRP, POSTN, and SPP1 protein. (A) and (B) Immunohistochemical staining for PTHRP in control salivary gland tissue and K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor tissue respectively. Note the conspicuous expression of PTHRP (white arrowhead) in the K5:RANKL tumor tissue compared to control. (C) and (D) Immunohistochemical detection of POSTN in control salivary gland tissue and K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor tissue respectively. While there are low levels of POSTN expression in control salivary gland tissue, note the marked increase in POSTN expression in the extracellular matrix of the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor tissue (black arrowhead). (E) and (F) Immunohistochemical staining for SPP1 in control salivary gland tissue and K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor tissue respectively. Note the prominent expression of SPP1 in the epithelial (white arrowhead) and stromal (black arrowhead) compartments of the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor tissue (inset shows a higher magnification of the stroma area that expresses SPP1 (black arrowhead)). Scale bars indicate 100μm (scale bar in (A) applies to (B-F (excluding the inset)).

DISCUSSION

Advancement in the development of effective molecular diagnostics and targeted therapeutics for the clinical management of salivary gland malignancies has been hampered by the limited availability of suitable experimental models, particularly in vivo models such as the mouse. As clearly demonstrated for cancers of other glandular tissues (i.e. the mammary gland), mouse models for these cancers have been successfully used not only for gaining essential insights into the molecular mechanisms that underpin all stages of tumor development and progression but also to test investigational and repurposed drugs as possible novel anti-neoplastic therapies.

In transgenic mouse studies described here, we demonstrate that targeting RANKL to K5 positive basal cells of the salivary gland epithelium elicits rapid tumorigenesis. The predominant histopathology of a high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma exhibited by these tumors is clinically significant as this tumor subtype is the most common salivary gland malignancy40, 41, 57 and has recently been shown to express RANKL and RANK36. Moreover, patients with high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas have low survival rates and high morbidity following treatment due in part to tumor resistance to conventional platinum-based chemotherapy and ionizing radiation58–60. Recent studies have also shown that mucoepidermoid carcinomas express high basal levels of NFkB, which may contribute to their chemoresistance and radioresistance58, 60. In the same studies, targeting NFkB signaling in a combined therapy protocol was shown to be effective in markedly reducing the resistance phenotype of human mucoepidermoid carcinoma cell lines in culture58, 60. Because many activators and mediators of the NFkB pathway are markedly up-regulated in the salivary gland tumor of the K5:RANKL mouse (Figures 3, 4 and Supplementary Table 1), this transgenic represents a potentially important preclinical model in which to test the efficacy of these new mechanism-based therapeutic approaches in an in vivo context.

Using the K5:RANKL mouse, together with genome-wide RNA profiling, we disclosed a complex transcriptomic signature that underlies salivary gland tumorigenesis in response to short-term RANKL exposure. Despite this complexity, gene set enrichment analysis and pathway analytics revealed a significant enrichment of transcriptional programs that exert important functions in cellular proliferation, communication, migration, and signaling to the extracellular matrix or tumor microenvironment. These transcriptional programs are reflective of an aggressive tumor phenotype, with potential for locoregional invasion and distant metastasis. Through cross-species analysis, we showed that the transcriptomic signature of the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor is most closely related to mesenchymal/basal subtypes of human head neck squamous cell carcinomas; mucoepidermoid carcinomas are not profiled by TCGA. Lending strong translational support for our mouse studies, the genes stratified in this analysis represent evolutionary conserved molecular targets that may prove important in the development of new molecular diagnostics and/or therapeutics in the future clinical management of salivary gland malignancies. As a corollary, the K5:RANKL transcriptomic dataset is also closely related to the human kidney renal clear cell carcinoma signature (Figure 5A (KIRC)). This finding is interesting as RANKL/RANK signaling has recently been linked to poor prognosis in patients diagnosed with renal clear cell carcinoma61 and supports the K5:RANKL transcriptomic signature as a powerful informational resource with which to molecularly understand RANKL-dependent cancers outside the head and neck cancer group.

In addition to RNA expression, we validated at the protein level the upregulation of three of these genes (PTHRP; POSTN; and SPP1) in the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor. Apart from its role in humoral hypercalcemia and bone resorption62, PTHRP is implicated in promoting metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinomas to bone63–65. Furthermore, studies support a role for PTHRP in conferring malignant potential to human mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the head and neck region66, suggesting that PTHRP may be used as a prognostic factor for this malignancy type. Interestingly, previous studies have shown a close correlation between PTHRP and RANKL expression in a number of cancers67–70, particularly in oral cancers that invade bone70–73. A secreted extracellular matrix protein, POSTN overexpression is also known as a prognostic indicator of poor survival for many cancers74, including head and neck cancers (75–79). An extracellular matrix protein, SPP1 is involved in tumor cell proliferation, invasion, and chemoresistance metastasis in a number of cancer types, such as nasopharyngeal and esophageal malignancies (80–82). Taken together, our immunohistochemical analysis reinforces the robustness of the K5:RANKL salivary gland tumor model with which to study both established and novel oncogenic drivers of human salivary gland tumorigenesis in an in vivo context.

Apart from providing a new genome-wide transcriptomic resource to gain better insight into the key molecular mechanisms that drive development and progression of this understudied salivary gland malignancy, further mining of this resource may reveal novel molecular vulnerabilities that could be exploited for future targeted therapies. In future studies, the K5:RANKL mouse will be used to determine whether RANKL-dependent enlargement and activation of the cancer stem cell population drives the development of this tumor-type and whether these tumor cells exhibit intrinsic metastatic potential. Noteworthy, enlargement and intrinsic activation of the cancer stem cell population by RANKL has been shown to be a common cellular underpinning for the development and metastatic properties of other glandular tissue cancers such as the mammary gland83. Finally, the K5:RANKL mouse represents an attractive preclinical in vivo model with which to assess the preventative and/or treatment efficacies of RANKL inhibitors in combination with other anti-neoplastic agents in the clinical management of this malignant neoplasm.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jie Li, Yan Ying, and Rong Zhao for their invaluable technical assistance in these studies. The technical services of the Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell, Genetically Engineered Mouse, Human Tissue Acquisition and Pathology Cores as well as the Genomic & RNA Profiling core at Baylor College of Medicine are acknowledged. These cores were funded by NIH P30 Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI-P30 CA125123), the P30 Digestive Disease Center Support Grant (NIDDK-DK56338), and the Knockout Mouse Project KOMP3 Grant (U42HG006352). For initial bioinformatic support, we thank Dr. Qianxing Mo at the Department of Medicine and Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine. This research was also supported in part by Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT: RP170005) to KR and CC, and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant: HD-042311 to JPL.

Grant numbers: NIH (NICHD): HD-042311 (JPL); CPRIT: RP170005 (KR; CC); NCI P30: CA125123 (MMI)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest concerning the studies described herein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boukheris H, Curtis RE, Land CE, Dores GM (2009). Incidence of carcinoma of the major salivary glands according to the WHO classification, 1992 to 2006: a population-based study in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18: 2899–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andry G, Hamoir M, Locati LD, Licitra L, Langendijk JA (2012). Management of salivary gland tumors. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 12: 1161–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes E, Eveson J, Reichart P (2005). World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of head and neck in tumours. IARCpress: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandana SR, Conley BA (2008). Salivary gland cancers: current treatments, molecular characteristics and new therapies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 8: 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langendijk JA, Doornaert P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Aaronson NK, Slotman BJ (2008). Impact of late treatment-related toxicity on quality of life among patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 26: 3770–3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sciubba JJ, Goldenberg D (2006). Oral complications of radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 7: 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FK, Burlage FR, Coppes RP (2003). Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 14: 199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurie SA, Licitra L (2006). Systemic therapy in the palliative management of advanced salivary gland cancers. J Clin Oncol 24: 2673–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Posner MR, Ervin TJ, Weichselbaum RR, Fabian RL, Miller D (1982). Chemotherapy of advanced salivary gland neoplasms. Cancer 50: 2261–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell D, Hanna EY (2012). Salivary gland cancers: biology and molecular targets for therapy. Curr Oncol Rep 14: 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson J, Licitra L, Locati L, Raben D, Persson F, Stenman G (2013). Salivary gland cancer: an update on present and emerging therapies. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book: 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razak AR, Siu LL, Le Tourneau C (2010). Molecular targeted therapies in all histologies of head and neck cancers: an update. Curr Opin Oncol 22: 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surakanti SG, Agulnik M (2008). Salivary gland malignancies: the role for chemotherapy and molecular targeted agents. Semin Oncol 35: 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dougall WC, Chaisson M (2006). The RANK/RANKL/OPG triad in cancer-induced bone diseases. Cancer Metastasis Rev 25: 541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Valdivia R, Lydon JP (2012). From the ranks of mammary progesterone mediators, RANKL takes the spotlight. Mol Cell Endocrinol 357: 91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh MC, Choi Y (2014). Biology of the RANKL-RANK-OPG System in Immunity, Bone, and Beyond. Front Immunol 5: 511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima T, Kobayashi Y, Yamasaki S, Kawakami A, Eguchi K, Sasaki H et al. (2000). Protein expression and functional difference of membrane-bound and soluble receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand: modulation of the expression by osteotropic factors and cytokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 275: 768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galibert L, Tometsko ME, Anderson DM, Cosman D, Dougall WC (1998). The involvement of multiple tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR)-associated factors in the signaling mechanisms of receptor activator of NF-kappaB, a member of the TNFR superfamily. J Biol Chem 273: 34120–34127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao S, Cronin SJF, Sigl V, Penninger JM (2018). RANKL and RANK: From Mammalian Physiology to Cancer Treatment. Trends Cell Biol 28: 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayer CM, Beckmann MW, Fasching PA (2017). Updates on the role of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB/receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand/osteoprotegerin pathway in breast cancer risk and treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 29: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisay M, Mengistu G, Edessa D (2017). The RANK/RANKL/OPG system in tumorigenesis and metastasis of cancer stem cell: potential targets for anticancer therapy. Onco Targets Ther 10: 3801–3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein MS, Ephros HD, Epstein JB (2013). Review of current literature and implications of RANKL inhibitors for oral health care providers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 116: e437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furuta H, Osawa K, Shin M, Ishikawa A, Matsuo K, Khan M et al. (2012). Selective inhibition of NF-kappaB suppresses bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma in vivo. Int J Cancer 131: E625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimm M, Renz C, Munz A, Hoefert S, Krimmel M, Reinert S (2015). Co-expression of CD44+/RANKL+ tumor cells in the carcinogenesis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Odontology 103: 36–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jimi E, Shin M, Furuta H, Tada Y, Kusukawa J (2013). The RANKL/RANK system as a therapeutic target for bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma (Review). Int J Oncol 42: 803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambandam Y, Ethiraj P, Hathway-Schrader J, Novince C, Panneerselvam E, Sundaram K et al. (2018). Autoregulation of RANK Ligand in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Tumor Cells. J Cell Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambandam Y, Sakamuri S, Balasubramanian S, Haque A (2016). RANK Ligand Modulation of Autophagy in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Tumor Cells. J Cell Biochem 117: 118–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambandam Y, Sundaram K, Liu A, Kirkwood KL, Ries WL, Reddy SV (2013). CXCL13 activation of c-Myc induces RANK ligand expression in stromal/preosteoblast cells in the oral squamous cell carcinoma tumor-bone microenvironment. Oncogene 32: 97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato K, Lee JW, Sakamoto K, Iimura T, Kayamori K, Yasuda H et al. (2013). RANKL synthesized by both stromal cells and cancer cells plays a crucial role in osteoclastic bone resorption induced by oral cancer. Am J Pathol 182: 1890–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin M, Matsuo K, Tada T, Fukushima H, Furuta H, Ozeki S et al. (2011). The inhibition of RANKL/RANK signaling by osteoprotegerin suppresses bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis 32: 1634–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, Junior CR, Liu M, Li F, D’Silva NJ, Kirkwood KL (2013). Oral squamous carcinoma cells secrete RANKL directly supporting osteolytic bone loss. Oral Oncol 49: 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blake ML, Tometsko M, Miller R, Jones JC, Dougall WC (2014). RANK expression on breast cancer cells promotes skeletal metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 31: 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canon JR, Roudier M, Bryant R, Morony S, Stolina M, Kostenuik PJ et al. (2008). Inhibition of RANKL blocks skeletal tumor progression and improves survival in a mouse model of breast cancer bone metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis 25: 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones DH, Nakashima T, Sanchez OH, Kozieradzki I, Komarova SV, Sarosi I et al. (2006). Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature 440: 692–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Liu Y, Wu B, Dong Z, Wang Y, Lu J et al. (2014). Potential role of the OPG/RANK/RANKL axis in prostate cancer invasion and bone metastasis. Oncol Rep 32: 2605–2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franchi A, Taverna C, Simoni A, Pepi M, Mannelli G, Fasolati M et al. (2018). RANK and RANK Ligand Expression in Parotid Gland Carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eveson J (2005). Tumors of the salivary glands In: Barnes L, Sidransky D (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology & Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. IARC; pp 209–281. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seethala RR (2009). An update on grading of salivary gland carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol 3: 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seifert G, Sobin L (1991). Histological Typing of Salivary Gland Tumors (WHO. World Health Organization) Second edn Springer-Verlag: Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goode RK, Auclair PL, Ellis GL (1998). Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the major salivary glands: clinical and histopathologic analysis of 234 cases with evaluation of grading criteria. Cancer 82: 1217–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luna MA (2006). Salivary mucoepidermoid carcinoma: revisited. Adv Anat Pathol 13: 293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szwarc MM, Kommagani R, Jacob AP, Dougall WC, Ittmann MM, Lydon JP (2015). Aberrant Activation of the RANK Signaling Receptor Induces Murine Salivary Gland Tumors. PLoS One 10: e0128467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raimondi AR, Vitale-Cross L, Amornphimoltham P, Gutkind JS, Molinolo A (2006). Rapid development of salivary gland carcinomas upon conditional expression of K-ras driven by the cytokeratin 5 promoter. Am J Pathol 168: 1654–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vitale-Cross L, Amornphimoltham P, Fisher G, Molinolo AA, Gutkind JS (2004). Conditional expression of K-ras in an epithelial compartment that includes the stem cells is sufficient to promote squamous cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 64: 8804–8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukherjee A, Soyal SM, Li J, Ying Y, He B, DeMayo FJ et al. (2010). Targeting RANKL to a specific subset of murine mammary epithelial cells induces ordered branching morphogenesis and alveologenesis in the absence of progesterone receptor expression. FASEB J 24: 4408–4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukherjee A, Soyal SM, Li J, Ying Y, Szwarc MM, He B et al. (2011). A mouse transgenic approach to induce beta-catenin signaling in a temporally controlled manner. Transgenic Res 20: 827–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szwarc MM, Kommagani R, Peavey MC, Hai L, Lonard DM, Lydon JP (2017). A bioluminescence reporter mouse that monitors expression of constitutively active beta-catenin. PLoS One 12: e0173014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szwarc MM, Hai L, Gibbons WE, Peavey MC, White LD, Mo Q et al. (2018). Human endometrial stromal cell decidualization requires transcriptional reprogramming by PLZF. Biol Reprod 98: 15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S et al. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindgreen S (2012). AdapterRemoval: easy cleaning of next-generation sequencing reads. BMC Res Notes 5: 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL (2016). Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc 11: 1650–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frankish A, Uszczynska B, Ritchie GR, Gonzalez JM, Pervouchine D, Petryszak R et al. (2015). Comparison of GENCODE and RefSeq gene annotation and the impact of reference geneset on variant effect prediction. BMC Genomics 16 Suppl 8: S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chitsazzadeh V, Coarfa C, Drummond JA, Nguyen T, Joseph A, Chilukuri S et al. (2016). Cross-species identification of genomic drivers of squamous cell carcinoma development across preneoplastic intermediates. Nat Commun 7: 12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res 19: 1639–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spiro RH, Huvos AG, Berk R, Strong EW (1978). Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of salivary gland origin. A clinicopathologic study of 367 cases. Am J Surg 136: 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guimaraes DM, Almeida LO, Martins MD, Warner KA, Silva AR, Vargas PA et al. (2016). Sensitizing mucoepidermoid carcinomas to chemotherapy by targeted disruption of cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 7: 42447–42460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lagha A, Chraiet N, Ayadi M, Krimi S, Allani B, Rifi H et al. (2012). Systemic therapy in the management of metastatic or advanced salivary gland cancers. Oral Oncol 48: 948–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wagner VP, Martins MA, Martins MD, Warner KA, Webber LP, Squarize CH et al. (2016). Overcoming adaptive resistance in mucoepidermoid carcinoma through inhibition of the IKK-beta/IkappaBalpha/NFkappaB axis. Oncotarget 7: 73032–73044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steven A, Leisz S, Fussek S, Nowroozizadeh B, Huang J, Branstetter D et al. (2018). Receptor activator of NF-kappaB (RANK)-mediated induction of metastatic spread and association with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wysolmerski JJ (2012). Parathyroid hormone-related protein: an update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 2947–2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lv Z, Wu X, Cao W, Shen Z, Wang L, Xie F et al. (2014). Parathyroid hormone-related protein serves as a prognostic indicator in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 33: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sen S, Dasgupta P, Kamath G, Srikanth HS (2018). Paratharmone related protein (peptide): A novel prognostic, diagnostic and therapeutic marker in Head & Neck cancer. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 119: 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takayama Y, Mori T, Nomura T, Shibahara T, Sakamoto M (2010). Parathyroid-related protein plays a critical role in bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol 36: 1387–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagamine K, Kitamura T, Yanagawa-Matsuda A, Ohiro Y, Tei K, Hida K et al. (2013). Expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein confers malignant potential to mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Oncol Rep 29: 2114–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumamoto H, Ooya K (2004). Expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), osteoclast differentiation factor (ODF)/receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) and osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor (OCIF)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) in ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med 33: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perez-Martinez FC, Alonso V, Sarasa JL, Manzarbeitia F, Vela-Navarrete R, Calahorra FJ et al. (2008). Receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) as a novel prognostic marker in prostate carcinoma. Histol Histopathol 23: 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zong JC, Wang X, Zhou X, Wang C, Chen L, Yin LJ et al. (2016). Gut-derived serotonin induced by depression promotes breast cancer bone metastasis through the RUNX2/PTHrP/RANKL pathway in mice. Oncol Rep 35: 739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cowan RW, Singh G, Ghert M (2012). PTHrP increases RANKL expression by stromal cells from giant cell tumor of bone. J Orthop Res 30: 877–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cui N, Nomura T, Takano N, Wang E, Zhang W, Onda T et al. (2010). Osteoclast-related cytokines from biopsy specimens predict mandibular invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Ther Med 1: 755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jimi E, Furuta H, Matsuo K, Tominaga K, Takahashi T, Nakanishi O (2011). The cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone invasion by oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis 17: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perez-Martinez FC, Alonso V, Sarasa JL, Nam-Cha SG, Vela-Navarrete R, Manzarbeitia F et al. (2007). Immunohistochemical analysis of low-grade and high-grade prostate carcinoma: relative changes of parathyroid hormone-related protein and its parathyroid hormone 1 receptor, osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand. J Clin Pathol 60: 290–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gonzalez-Gonzalez L, Alonso J (2018). Periostin: A Matricellular Protein With Multiple Functions in Cancer Development and Progression. Front Oncol 8: 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kudo Y, Ogawa I, Kitajima S, Kitagawa M, Kawai H, Gaffney PM et al. (2006). Periostin promotes invasion and anchorage-independent growth in the metastatic process of head and neck cancer. Cancer Res 66: 6928–6935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li M, Li C, Li D, Xie Y, Shi J, Li G et al. (2012). Periostin, a stroma-associated protein, correlates with tumor invasiveness and progression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis 29: 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Michaylira CZ, Wong GS, Miller CG, Gutierrez CM, Nakagawa H, Hammond R et al. (2010). Periostin, a cell adhesion molecule, facilitates invasion in the tumor microenvironment and annotates a novel tumor-invasive signature in esophageal cancer. Cancer Res 70: 5281–5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qin X, Yan M, Zhang J, Wang X, Shen Z, Lv Z et al. (2016). TGFbeta3-mediated induction of Periostin facilitates head and neck cancer growth and is associated with metastasis. Sci Rep 6: 20587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Underwood TJ, Hayden AL, Derouet M, Garcia E, Noble F, White MJ et al. (2015). Cancer-associated fibroblasts predict poor outcome and promote periostin-dependent invasion in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Pathol 235: 466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Celetti A, Testa D, Staibano S, Merolla F, Guarino V, Castellone MD et al. (2005). Overexpression of the cytokine osteopontin identifies aggressive laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas and enhances carcinoma cell proliferation and invasiveness. Clin Cancer Res 11: 8019–8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Le QT, Sutphin PD, Raychaudhuri S, Yu SC, Terris DJ, Lin HS et al. (2003). Identification of osteopontin as a prognostic plasma marker for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 9: 59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin J, Myers AL, Wang Z, Nancarrow DJ, Ferrer-Torres D, Handlogten A et al. (2015). Osteopontin (OPN/SPP1) isoforms collectively enhance tumor cell invasion and dissemination in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 6: 22239–22257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Palafox M, Ferrer I, Pellegrini P, Vila S, Hernandez-Ortega S, Urruticoechea A et al. (2012). RANK induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness in human mammary epithelial cells and promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res 72: 2879–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.