Significance

Some jurisdictions ban markets regarded as repugnant. However, many bans foster black markets when the population insufficiently shares the repugnance that inspires the ban. Relationships between repugnance and regulation are important for understanding both when markets can operate effectively and when they can effectively be banned. We conduct surveys in Germany, Spain, the Philippines, and the United States about three controversial markets—prostitution, surrogacy, and global kidney exchange (GKE). Prostitution is the only one banned in the United States and the Philippines and only one allowed in Germany and Spain. Unlike prostitution, majorities support legalization of surrogacy and GKE in all four countries. There is not a simple relation between public support for markets, or bans, and their regulatory status.

Keywords: repugnance, global kidney exchange, surrogacy, prostitution

Abstract

We study popular attitudes in Germany, Spain, the Philippines, and the United States toward three controversial markets—prostitution, surrogacy, and global kidney exchange (GKE). Of those markets, only prostitution is banned in the United States and the Philippines, and only prostitution is allowed in Germany and Spain. Unlike prostitution, majorities support legalization of surrogacy and GKE in all four countries. So, there is not a simple relation between public support for markets, or bans, and their legal and regulatory status. Because both markets and bans on markets require social support to work well, this sheds light on the prospects for effective regulation of controversial markets.

Many transactions are potentially repugnant in the sense that some people would like to engage in them, while others think no one should be allowed to do so, even though those others may not face any easily measurable negative externalities themselves from the transactions in question (1–5). Markets widely regarded as repugnant may lack the social support needed to function efficiently.

Some jurisdictions enact legal or regulatory bans on markets regarded as repugnant. However, bans also require social support to be effective. Many bans foster black markets when the population insufficiently shares the repugnance that inspires the ban. Furthermore, outlawing markets may be especially ineffective when those markets operate legally in other accessible jurisdictions. So, the relationships between repugnance, legislation, and jurisdiction tourism are important for understanding both when markets can operate effectively and when they can effectively be banned.

This paper investigates the relationship between repugnance and legislation or regulation to forbid certain transactions. We consider three transactions involving human bodies that face substantial repugnance expressed in very general terms and yet, are legal in some jurisdictions and illegal (or administratively banned) in others. We survey sample populations in four relevant countries to determine the extent and intensity of popular repugnance and of support for letting those markets operate legally.

A natural hypothesis for why different jurisdictions have different laws supporting or banning particular markets is that these laws reflect the sentiment of the local populations regarding the acceptability of the transactions in question.

This hypothesis receives some support from the substantial literature surveying populations in different countries about their attitudes toward prostitution. We further test this hypothesis by examining attitudes in the United States, Germany, Spain, and the Philippines toward prostitution, surrogacy, and kidney exchange, especially across international borders between richer and poorer countries.

The laws or regulations regarding these three transactions are precisely the opposite when we compare the United States with Germany, or with Spain, and their legal status is the subject of contemporary debate in many places. One of the goals of this study is to inform that debate.

Prostitution is the only one of these three transactions legal in Germany, and the only one illegal across the United States (except for some rural counties in Nevada).* In Spain, as in Germany, prostitution is legal, and surrogacy is illegal, in ways that make it difficult for German and Spanish couples who use legal surrogates elsewhere to bring their children home (although Spanish and German courts are finding pathways for this to happen). Kidney exchange is not allowed by German transplant law. It is in fact legal in Spain, but regulations banning citizens of poor countries from participating in such exchanges have been enacted. In the Philippines, laws forbid prostitution (but there is nevertheless an active black market, including for foreign sex tourism). Philippine laws do not forbid surrogacy or kidney exchange, and Philippine citizens have benefited from legally participating in global kidney exchange (GKE) transactions in the United States (6, 7). Fig. 1 shows a summary of the legal status of these transactions in these countries.†

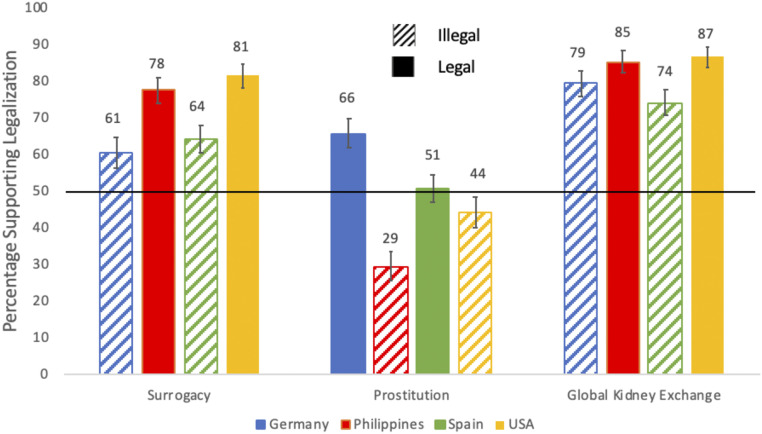

Fig. 1.

Percentage of respondents who support legalization by scenario and country.

Foreshadowing our main results, Fig. 1 also displays the percentage of respondents in each country who respond that they are in favor of having each of these transactions available legally.

It turns out that prevailing local law is not a good predictor of popular sentiment in this regard.‡ Both in countries where it is legal and where it is not, three-quarters or more of the respondents answer that they favor having GKE be legal. Smaller majorities report favoring legal surrogacy, both where it is legal and where it is not. So, it is not the case that legislation necessarily reflects or is reflected in broad popular opinion about whether these transactions should be legally available. Prostitution is different: only minorities report favoring legalization in the places where it is presently illegal, and it is too close to call in Spain, where it is legal.

Background: Repugnant Transactions, Monetary Payments, and Related Literature

Transactions involving human bodies are a good place to study laws and repugnance because repugnance to these transactions has been phrased in very general terms. (See ref. 10 for further background.) For example, the Council of Europe (11) declares “The human body and its parts shall not, as such, give rise to financial gain.” This also points to the repugnance of monetary payments: the introduction of payment sometimes causes otherwise unrepugnant transactions to become repugnant.§

Each of the three transactions we address involves human bodies. Prostitution also involves monetary payments from one side of the transaction to the other: payment is often one of the defining features of prostitution in related legislation. Surrogacy may or may not involve payments to the surrogate beyond reimbursement of direct expenses: when it does, it is called “commercial surrogacy.” Although all surrogacy is illegal in some countries, in other countries surrogacy is legal, but payments to surrogates beyond expenses are not (i.e., commercial surrogacy is banned). Kidney exchange does not involve any payments to the participants, and it in fact arises to increase transplantation without violating almost universal bans on paying kidney donors (which themselves result in black markets in some countries).¶ We discuss each of these below, in just enough detail to explain our survey strategy, and with pointers to the literature.

Kidney Exchange and GKE

Healthy people have two kidneys and can remain healthy with one, so living donation of a kidney can save the life of a kidney failure patient, particularly since the supply of deceased-donor kidneys falls far short of the need. (For further background, see refs. 18 and 19.) However, it is illegal almost everywhere in the world to pay a donor for a kidney, and because kidneys need to be well matched to their recipients, often willing donors cannot donate to the patient they love. Kidney exchange allows such donors to nevertheless help their loved ones by exchange with other patient–donor pairs, so each patient receives a compatible kidney from another patient’s donor (20). It has become a standard form of transplantation in the United States, particularly after Congress passed, without dissenting votes (i.e., with no evident repugnance), an amendment to the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984 specifying that the act’s ban on giving donors “valuable consideration” did not apply to kidney exchange, in which no donor receives payment.# Kidney exchange has begun to be organized in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, and to a much smaller extent in Spain and elsewhere (22). In Germany, it is essentially banned by the law governing transplantation, which specifies that (except in special circumstances, with judicial intervention) a person can only receive a living kidney from a member of their immediate family (23).

In rich countries, in which kidney exchange is most active, there remain hard-to-match patient–donor pairs, typically because the patient is “highly sensitized,” with many antibodies to human proteins. Such patients can only receive a transplant if a rare kidney that would work for them becomes available, so they benefit from enlarging the set of patient–donor pairs available for exchange. Meanwhile, kidney failure has become a leading cause of death in middle-income countries, such as the Philippines, in which the national health insurance does not cover the costs of transplantation.‖ Recently, in the United States, a program of GKE across international borders has been piloted, in which foreign patient–donor pairs can participate in American kidney exchange, under the same terms as Americans. One obstacle facing such a program is to pay for costs that are not fully covered for all parties, and this becomes possible because transplantation is much cheaper than dialysis; therefore, the savings to a rich country’s medical system from taking a patient off dialysis can pay for all of the costs of the foreign patient–donor pair, including their costs after returning to their home country. No patients or donors are paid. GKE has been endorsed by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (25), by the European Society of Transplantation (26), and by eminent moral philosophers in The Lancet (27). However, in Spain and elsewhere, such programs have also been opposed by members of the transplant establishment, who have succeeded in passing European Union regulations forbidding it by analogy to laws forbidding organ trafficking and transplant tourism to countries with active black markets in which organs can be illegally purchased (28).**

Surrogacy, Commercial Surrogacy, and International Fertility Tourism

A gestational surrogate is a woman who becomes pregnant with a child to whom she is not genetically related, for someone else (i.e., without the intention of assuming parental rights). (See ref. 35 for further background.) It was technologically enabled by the 1970s development of in vitro fertilization (IVF), which allows an egg to be fertilized with sperm outside the body (“in vitro”) and for the resulting embryo to be implanted in the womb to begin pregnancy. IVF quickly became a medically available form of assisted reproduction technology (ART), although ART itself is in some places banned as a repugnant transaction, often with exceptions for married couples with medically certified infertility. In the absence of laws concerning surrogacy, the occasional surrogacies that resulted in custody battles were adjudicated in family courts, with differing results in different jurisdictions, which subsequently passed a variety of laws. These range from outlawing surrogacy (and regarding the surrogate as the legal mother of the child, without parental rights to the intended parents) to fully legalizing commercial surrogacy. In Spain and Germany, where surrogacy is outlawed, this has led to numerous cases of intended parents traveling to foreign jurisdictions for surrogacy but then having difficulty in repatriating their children (see, e.g., refs. 36 and 37). Some countries ban commercial surrogacy but allow unpaid “altruistic surrogacy,” including protections of rights of the intended parents, surrogate, and child. In many American states, particularly California, commercial surrogacy is fully legal, with reliable customary contracts, and the intended parents appear as the parents on the child’s birth certificate. California is consequently a popular fertility-tourism destination for parents seeking surrogacy.††

Prostitution and International Sex Tourism

Unlike kidney transplantation and surrogacy, prostitution does not depend on recent technological innovations: some forms are probably older than agriculture. (See ref. 40 for more background.) Prostitution is illegal in all American states except (parts of) Nevada, including extraterritorial bans on international sex tourism involving minors. (See ref. 41.) Prostitution is legal and regulated in various ways in many European countries, including Spain and Germany, which allow sex work by self-employed adults. Some previous cross-country studies (42, 43) have found that citizens in countries where prostitution is criminalized hold less tolerant attitudes toward it, while others have found mixed results (44, 45; ref. 46 has an intertemporal/cross-sectional study in the United States).

Materials and Methods

We designed a survey that asks respondents in Germany, the Philippines, Spain, and the United States to make moral and legal judgments about three comparable scenarios involving surrogacy, prostitution, and GKE. Survey responses are sensitive to framing, and so, we begin with some remarks that guided our construction of the scenarios to which the respondents were asked to react.

To allow comparisons, all of the scenarios deal with international transactions involving individuals in a rich country and the Philippines. In the Philippines, the rich country was the United States, and it was the United States, Spain, or Germany for survey participants in those countries, respectively. This fits the situation of the first GKEs and makes comparisons easier among all three transactions. Scenarios were presented in the local languages, namely English, Spanish, German, and Filipino (Tagalog).

The GKE scenario began with a brief description of kidney exchange:

A kidney for transplant must be compatible with the recipient’s blood type and immunological system. A kidney can come from a compatible deceased donor, or from a healthy compatible living donor. In case a living donor wishes to give a kidney to a particular patient but is incompatible, kidney exchange is another possibility, in which two patient–donor pairs exchange kidneys, so that each patient receives a compatible kidney from the other patient’s donor.

Participants were then introduced to the specific scenario:

James and Erica are a married couple in [home country]. James needs a kidney, but Erica is an incompatible donor. There isn’t a compatible match for him anywhere in [home country]. Maria is a married mother in the Philippines whose husband needs a kidney transplant but cannot afford one. Maria and her husband can do a kidney exchange with James and Erica. It would save the [home country] insurance company enough money so they could pay for the surgery for the Filipino pair, who could then get postoperative care back home.

To make transactions comparable, surrogacy and prostitution were also investigated in the same international context involving James, Erica, Maria, and her husband.

In the surrogacy scenario, because some legal and regulatory bans on surrogacy make an exception for medically certified infertility, we avoided this possible exception for regarding surrogacy as repugnant by making clear that the couple’s motivation for seeking a surrogate was not infertility or any other medical reason.

The participants were first given a brief explanation of surrogacy: “A surrogate mother is a woman who bears a child for another woman, often for pay, through in vitro fertilization (IVF).”

They were then introduced to the specific scenario:

James and Erica are a married couple in [home country]. They want to have a child, but Erica does not want to become pregnant due to the demands of her career as a model. Maria is a married mother in the Philippines. Maria’s husband is out of work, and Maria has decided to become a surrogate mother to earn additional income. James and Erica hire Maria to carry and give birth to a child from James and Erica’s sperm and egg. James and Erica pay Maria a year’s average income in the Philippines, and everyone signs a contract making it clear that James and Erica are the child’s biological parents and will have custody after the child is born.

The prostitution scenario was not introduced with an explanation of what constitutes prostitution (partly because that is contentious). We let the scenario speak for itself:

James is an unmarried man in [home country]. Maria is a married mother in the Philippines. Maria’s husband is out of work, and Maria has decided to become a prostitute to earn additional income. James visits the Philippines regularly for work, and regularly hires Maria for her services. James pays Maria a year’s average income in the Philippines.

After reading each scenario, the participants were asked to make a series of ethical judgments about the exchange. Specifically, they were instructed to “answer the following questions using a 0 to 100 scale: 0 to 14%: Definitely No; 15 to 39%: Probably No; 40 to 59%: Uncertain; 60 to 84%: Probably Yes; 85 to 100%: Definitely Yes.” The first issue was whether the couple uses Maria in this exchange, and if so, if it poses an ethical problem. Next, they were asked if they think the exchange is ethical in general. The participants are then asked, “should this exchange be legal or illegal?” (These are the answers displayed in Fig. 1.) They were also asked how strongly they felt about their answer to this question on a scale from 0 to 100. Finally, they had to decide whether the couple, Maria, both, or neither should be punished if the exchange is not permitted.

Participants in the United States, Germany, Spain, and the Philippines were recruited through Respondi (https://www.respondi.com/EN/). Respondi maintains its own panel of respondents in Germany and Spain and worked with Prodege (https://www.prodege.com/) for the US panel and dataSpring (https://www.d8aspring.com/) for the Philippines panel. The participants were paid to complete the survey based on the length of time taken, at the usual Respondi rate. We first ran pilot surveys in Germany, Spain, and the United States with a target of 100 respondents each. The respondents did not indicate any confusion when they had the opportunity to give feedback at the end of the survey. We then targeted 400 more respondents for each of these countries for a total of 500.‡‡ We subsequently conducted the survey in the Philippines with a target of 500 respondents. All surveys were fielded in the native language (translations were done via Upwork). Respondi aimed for representative samples in terms of gender, age, and regions. Table 1 presents the gender, age, and education breakdown by country.§§ This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board and informed consent was not required.

Table 1.

Summary of respondent demographics by country

| Country | Female | 18–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75+ | College degree |

| Germany | 46.92 | 7.85 | 21.12 | 22.06 | 21.68 | 26.36 | 0.93 | 0 | 24.86 |

| The Philippines | 51.85 | 50.88 | 17.93 | 12.09 | 7.99 | 7.02 | 4.09 | 0 | 63.55 |

| Spain | 54.63 | 4.94 | 21.14 | 31.17 | 26.70 | 12.96 | 2.93 | 0.15 | 58.95 |

| The United States | 48.20 | 6.99 | 25.14 | 21.17 | 18.15 | 22.12 | 6.43 | 0 | 46.69 |

After they had responded to the questions about each scenario, the order being surrogacy followed by prostitution followed by GKE, participants were asked two questions about attitudes toward immigration, specifically whether they want more or fewer immigrants separately from high-income countries and low-income countries on a 0 to 100 scale. Finally, they answered some standard demographic, political, and religious attitudes questions. Data and associated material are available at https://osf.io/w7u9f/.

Results

Fig. 1 summarizes the proportion of participants who think the three scenarios should be legal in each of the four countries. For both surrogacy and GKE, the proportions are all significantly greater than 50% (P < 0.01; i.e., both where it is legal and where it is banned). In contrast, the proportion of participants who believe the prostitution scenario should be legal is significantly below 50% in both the Philippines and the United States (P < 0.01) and not significantly different from 50% in Spain. The proportion is only significantly greater than 50% in Germany (P < 0.01).

We can also compare the proportion of participants who supported legality for each scenario across countries. For surrogacy, the proportions are not significantly different between the Philippines and the United States nor between Germany and Spain. However, the gap between these two sets of countries is significant (P < 0.01). For the prostitution scenario, all pairwise comparisons between countries are significantly different (P < 0.01; P < 0.05 for the comparison between Spain and the United States). The proportion of participants who think the GKE scenario should be legal in Germany is significantly less than in the Philippines (P = 0.01) and the United States (P < 0.01) and significantly more than in Spain (P < 0.05). Similarly, the proportion of participants who support legality in Spain is significantly less than in the Philippines and the United States (P < 0.01). Finally, there is no significant difference between the proportion of participants who believe the scenario should be legal in the Philippines and in the United States.

So, there is a correlation between expressions of support for legality and the current legal status as evident in Table 2. The coefficient on the current law dummy (legal = 1) in the probit regression with support for legality as the dependent variable is significantly positive (P < 0.05) for all three scenarios.

Table 2.

Probit regression of support for legality on current law in country, age (under 35 dummy), and other demographic and opinion variables

| Surrogacy | Prostitution | GKE | |

| Current law | 0.19 (0.023) | 0.17 (0.026) | 0.11 (0.020) |

| Under 35 | 0.034 (0.023) | −0.026 (0.026) | 0.0067 (0.020) |

| Income level | 0.0070 (0.0034) | 0.0032 (0.0037) | 0.0074 (0.0029) |

| College degree | −0.0016 (0.020) | −0.027 (0.023) | 0.0097 (0.017) |

| Unemployed and looking | 0.0025 (0.037) | −0.042 (0.041) | 0.015 (0.030) |

| Single | −0.045 (0.028) | −0.0056 (0.031) | −0.014 (0.024) |

| Children (dummy) | 0.016 (0.026) | 0.0095 (0.028) | 0.0027 (0.022) |

| Atheist | 0.027 (0.025) | 0.076 (0.029) | 0.014 (0.021) |

| Religion intensity | −0.097 (0.030) | −0.15 (0.030) | −0.081 (0.027) |

| Social conservative | −0.042 (0.024) | 0.031 (0.026) | −0.016 (0.020) |

| Immigration from high-income countries | 0.00061 (0.00045) | 0.0010 (0.0005) | −0.00019 (0.00038) |

| Immigration from low-income countries | −0.00060 (0.00045) | 0.00058 (0.0005) | −0.00034 (0.00038) |

| N | 2,225 | 2,225 | 2,225 |

All coefficients are stated as marginal effects. Current law = 1 if legal. There are 12 income levels. Religious intensity = 1 if religious attendance is at least once a week.

That there is a correlation between the current laws and the sentiment in favor of them, despite the disconnect between the current laws and their level of support, might suggest that in the past, when legislation was enacted, the legislative decision had majority support but that this has declined over time. However, in this case, we might expect to find that younger respondents were more in favor of legalization of surrogacy and kidney exchange, and this is not the case. The coefficient on the under 35 age dummy is not significantly different from zero for any of the scenarios. (This does not rule out the possibility that a change in attitude over time took place among all age groups equally.) Furthermore, since all three scenarios involve international transactions, we examined attitudes toward immigration, but those are mostly not significantly correlated with opinions about legality across scenarios, with the exception of a positive correlation between attitude toward immigration from high-income countries and prostitution. There is also a positive correlation between income level and support for legality of surrogacy and GKE but not for prostitution. Those who identify as atheists are more likely to think that the prostitution scenario should be legal (there is no significant correlation for the other two scenarios). We code the religious intensity dummy variable as one if the respondent answers either daily or once a week or more to the question of how often she/he attends religious services. The coefficient on this variable is significantly negative in the probit regressions for all three scenarios, suggesting that the most outwardly religious devout are less likely to support legality.

Of course, what may matter for the legal landscape is not simply the direction of the public’s opinion on the legality of these exchanges, but the intensity of their opinion as well. We asked for the strength of the participants’ opinion on the legality question on a 0 to 100 scale (0 to 14%: very weakly; 15 to 39%: somewhat weakly; 40 to 59%: uncertain; 60 to 84%: somewhat strongly; 85 to 100%: very strongly).

The results do not support the hypothesis that the legal status of transactions reflects the strength of opinion of those who support or oppose legality, specifically that those with the minority opinion hold it more strongly. For surrogacy, the proportion of respondents who feel strongly or very strongly about the scenario being legal vs. illegal is only significantly different (P < 0.05) for Germany (81% for legal and 72% for illegal). For prostitution, the proportions are significantly different for all countries (P < 0.01) except for Germany. In the other three countries, a greater proportion of respondents strongly or very strongly supports the scenario being illegal (the Philippines: 91 vs. 75%; Spain: 80 vs. 68%; the United States: 87 vs. 74%). For GKE, the proportions are significantly different for all countries (P < 0.01) except for the Philippines. In the other three countries, more respondents strongly or very strongly support legality (Germany: 80 vs. 63%; Spain: 74 vs. 60%; the United States: 83 vs. 61%). The results, summarized in SI Appendix, Table S1, are similar if we look at the average strength of these opinions instead.

Judgments about Ethicality, Whether Maria Is Being Used, and Whether That Is an Ethical Concern.

The respondents’ opinions about the ethicality of the three scenarios are in line with their thoughts on legality. For surrogacy, the average on the scale is 45 for Germany and 46 for Spain and higher for the Philippines and the United States at 55 and 62, respectively. For prostitution, Germany has a higher average at 47, mirroring the higher proportion of respondents who believed in legality, with an average of 35 for the Philippines and 38 for Spain and the United States. Finally, for GKE, the averages are 70 for Germany, 63 for the Philippines, 60 for Spain, and 72 for the United States.

Next, we summarize the cross-country opinions on whether Maria was used in each of the scenarios and whether that poses an ethical concern. For the surrogacy scenario, respondents judged that Maria was used an average of 60 on the scale in Germany, 66 in the Philippines, 56 in Spain, and 45 in the United States. On the related question of whether using Maria raises an ethical concern, the numbers are 55, 49, 55, and 40 for the four countries, respectively. For prostitution, respondents in the Philippines more strongly agreed that Maria was used, with an average of 77 compared with 61 for Germany, 63 for Spain, and 64 for the United States. They were also more likely to find it an ethical concern at 74 vs. 50, 62, and 65 for the other three countries, respectively. For GKE, the average response is again highest for the Philippines at 48, while it is 33 for Germany, 36 for Spain, and 30 for the United States. Respondents in all four countries did not find it to be much of an ethical concern, with a 32 average for Germany, 38 for the Philippines, 38 for Spain, and 31 for the United States.

Table 3 shows that the relationship between overall judgment about legality and the judgment on Maria being used as well whether that is an ethical concern varies across the scenarios and countries.

Table 3.

Relationship between overall judgment about legality and the judgment on Maria being used as well whether that is an ethical concern

| Surrogacy | Germany | The Philippines | Spain | The United States |

| Used Maria | −0.0083 (0.0024) | −0.0017 (0.0022) | −0.12 (0.0023) | −0.0015 (0.0028) |

| Ethical concern | −0.021 (0.0023) | −0.018 (0.0023) | −0.023 (0.0025) | −0.021 (0.0028) |

| Constant | 2.04 (0.17) | 1.87 (0.19) | 2.52 (0.18) | 2.08 (0.17) |

| Prostitution | ||||

| Used Maria | −0.0024 (0.0024) | −0.0043 (0.0023) | −0.0088 (0.0020) | −0.0058 (0.0020) |

| Ethical concern | −0.023 (0.0024) | −0.018 (0.0023) | −0.021 (0.0022) | −0.019 (0.0020) |

| Constant | 1.87 (0.16) | 1.05 (0.18) | 1.94 (0.16) | 1.48 (0.15) |

| GKE | ||||

| Used Maria | −0.013 (0.0029) | −0.0024 (0.0027) | −0.014 (0.0027) | −0.0025 (0.0029) |

| Ethical concern | −0.024 (0.0029) | −0.18 (0.0028) | −0.019 (0.0028) | −0.018 (0.0030) |

| Constant | 2.42 (0.17) | 2.02 (0.17) | 2.18 (0.14) | 1.97 (0.14) |

Discussion

We have considered three transactions that all involve human bodies (cf. 47). They differ in that (among other things) surrogacy and kidney exchange depend on the modern technologies of IVF and transplantation, respectively, while prostitution is ancient. Prostitution and surrogacy both involve payments for the (temporary) use of (typically women’s) bodies, while kidney exchange does not involve payments to or from participants but involves permanent donation of a body part. Each of these features could influence whether these transactions receive social support.

Our main result is that (unlike prostitution) the laws banning surrogacy and GKE do not seem to reflect popular demand. Neither do these bans reflect that opponents of legalization feel more strongly than supporters.

However (as with prostitution), there is some correlation between local law and peoples’ judgement of whether legality is desirable. Descriptively, Americans and Filipinos support legality of prostitution less than Spaniards or Germans (and less than they support surrogacy or GKE), Germans support legal surrogacy less than legal prostitution, and Germans and Spaniards support legal surrogacy and GKE less than Americans or Filipinos.

However, the evidence does not suggest that the disconnect between bans and majority support for legality is due to changes over time since support for legality is not correlated with age (i.e., it is unlikely that when the laws were passed, support was below 50% but that it has since risen since we should be able to detect that through different attitudes across age groups).

All three transactions are the subject of current debate in at least one of the countries we surveyed.¶¶ Based on the results of our surveys, we do not see entrenched popular resistance to either surrogacy or GKE (or simple kidney exchange) where it is presently illegal, and thus, we anticipate that efforts to lift or circumvent current restrictions are likely to be increasingly successful, while efforts to legalize or decriminalize prostitution where it is presently illegal may face greater opposition from the general public.

Understanding these issues is important, not just for the hundreds of Spanish couples stranded outside of Spain while they look for a way to bring their surrogate children home and not just for the people in need of kidney exchange but for whom it is out of reach in Germany or in the Philippines. These issues are also of importance to social scientists in general and economists in particular. When markets enjoy social support, when they are banned, and when, in turn, bans are socially supported are questions that touch upon many transactions, particularly as social and economic interactions are increasingly globalized.

Our findings suggest that the answer to these questions may not be found in general public sentiment in countries that ban markets or legalize them. Rather, we may have to look to the functioning of particular interested groups, perhaps with professional or even religious interests, that are able to influence legislation in the absence of strong views (or even interest) among the general public about the markets in question.##

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

Data deposition: Code and data from all surveys have been deposited in Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/w7u9f/).

*In cases involving children, the US ban on prostitution is extraterritorial and allows prosecution of individuals who have engaged in activities that are illegal in the United States even if they are legal in the country in which they occurred.

†Elías et al. (8) consider the legal status of prostitution and surrogacy in over 100 countries and report a steady increase in formal legislation from 1960 to 2015, with a growth in both statutory bans and explicit authorization and regulation.

‡See also Leuker et al. (9). Note that survey responses may be good indicators of peoples’ sentiment without being predictive of how they would vote in a counterfactual referendum in which contending parties would frame the issues differently.

§Other general arguments about repugnance sometimes involve a distaste for markets or their globalization generally [see, e.g., Sandel (12); see also, e.g., Tetlock et al. (13) for discussions of repugnance to monetary payments].

¶Surveys of repugnance to kidney sales are in Leider and Roth (14), Elías et al. (15), and particularly, Elías et al. (16) [see also Satel (17)].

#The Charlie W. Norwood Living Organ Donation Act passed the House by a vote of 422 to 0 on March 7, 2007 (https://www.govtrack.us/congress/votes/110-2007/h126) and passed the Senate under the rule of Unanimous Consent (https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/110/hr710) on December 6, 2007 (21).

‖Liyanage et al. (24) estimate that 2 to 7 million people die every year worldwide due to inability to pay for dialysis or kidney transplantation.

**Also, there are critiques by Delmonico and Ascher (29) and Wiseman and Gill (30) [and also in Spanish newspapers; e.g., ref. 31 and replies by Marino et al. (32), Rees et al. (7), and Roth et al. (33, 34)].

††In New York, commercial surrogacy became legal only in 2020, following an active debate in the legislature featuring politicians regarded as progressive on both sides (38, 39).

‡‡There were some delays in closing the surveys, so we actually had more than 500 respondents.

§§Comparisons with country demographics are in SI Appendix; we note that young people were overrepresented in our Philippines internet sample. We were also conservative in who we coded as having a college degree in Germany given the multiple education tracks.

¶¶Some Democratic candidates in upcoming elections have positions favoring legalization or decriminalization of prostitution (see, e.g., refs. 48 and 49), while the Fight Online Trafficking Act of 2017 (50) signed into law by President Trump facilitates prosecution. Similarly, debates swirl around surrogacy in New York State (38) and in Spain (51, 52), GKE in Spain and elsewhere (53), and kidney exchange in Germany (54).

##On coalitions of diverse interest groups (see, e.g., ref. 55) and on legislating morality (see, e.g., the debate between refs. 50 and 57 on the appropriateness of having public laws legislate private morality).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2005828117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Roth A. E., Repugnance as a constraint on markets. J. Econ. Perspect. 21, 37–58 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambuehl S., An offer you can’t refuse? Incentives change how we think. https://www.cesifo.org/DocDL/cesifo1_wp6296.pdf. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 3.Ambuehl S., Bernheim B. D., Ockenfels A., Projective paternalism. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26119. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 4.Ambuehl S., Ockenfels A., The ethics of incentivizing the uninformed. A vignette study. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 91–95 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambuehl S., Niederle M., Roth A. E., More money, more problems? Can high pay be coercive and repugnant? Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 357–360 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozek D. N. et al., Complete chain of the first global kidney exchange transplant and 3-yr follow-up. Eur. Urol. Focus 4, 190–197 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rees M. A. et al., Kidney exchange to overcome financial barriers to kidney transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 17, 782–790 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elías J. J., Lacetera N., Macis M., Salardi P., Economic development and the regulation of morally contentious activities. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 76–80 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leuker C., Samartzidis L., Hertwig R., What makes a market transaction morally repugnant? https://psyarxiv.com/dgz4s/ (23 April 2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Roth A., “Posts with label repugnance.” Market Design (2020). https://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/search/label/repugnance. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 11.Council of Europe , Additional protocol to the convention on human rights and biomedicine concerning transplantation of organs and tissues of human origin, article 21, Strasbourg, January 24, 2002. https://rm.coe.int/1680081562. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 12.Sandel M. J., What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (Macmillan, New York, NY, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tetlock P. E., Kristel O. V., Elson S. B., Green M. C., Lerner J. S., The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 853–870 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leider S., Roth A. E., Kidneys for sale: Who disapproves, and why? Am. J. Transplant. 10, 1221–1227 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elías J. J., Lacetera N., Macis M., Sacred values? The effect of information on attitudes toward payments for human organs. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 361–365 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elías J. J., Lacetera N., Macis M., Paying for kidneys? A randomized survey and choice experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 109, 2855–2888 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satel S., Organs for sale. https://www.aei.org/articles/organs-for-sale-2/. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 18.Roth A., “Posts with label kidney exchange.” Market Design (2020). https://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/search/label/kidney%20exchange. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 19.Roth A., “Posts with label global kidney exchange.” Market Design (2020). https://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/search/label/global%20kidney%20exchange. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 20.Roth A. E., Sönmez T., Utku Ünver M., Kidney exchange. Q. J. Econ. 119, 457–488 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 21.110th United States Congress, Charlie W. Norwood Living Organ Donation Act (2007). https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/710/text. Accessed 21 July 2020.

- 22.Biró P., et al. , Kidney practices in Europe. In first handbook of the COST action CA 15210: European network for collaboration on kidney exchange programmes (ENCKEP). https://www.enckep-cost.eu/news/news-first-handbook-of-the-cost-action-ca15210-57. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 23.Dücker S., Hörnle T., “German law on surrogacy and egg donation: The legal logic of restrictions” in Cross-Cultural Comparisons on Surrogacy and Egg Donation, Mitra S., Schicktanz S., Patel T., Eds. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), pp. 231–253. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liyanage T. et al., Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: A systematic review. Lancet 385, 1975–1982 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Transplant Surgeons , Position on global kidney exchanges, drafted and finalized by the ASTS executive committee, October 2017. https://asts.org/about-asts/position-statements#.Xv2we7V7nIV. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 26.Ambagtsheer F. et al., Global kidney exchange: Opportunity or exploitation? An ELPAT/ESOT appraisal. Transpl. Int., 10.1111/tri.13630 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minerva F., Savulescu J., Singer P., The ethics of the global kidney exchange programme. Lancet 394, 1775–1778 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Council of Europe , European committee on organ transplantation (CD-P-TO), European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare. Statement on the Global Kidney Exchange Concept, April 10, 2018. https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectID=09000016808aee9f. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 29.Delmonico F. L., Ascher N. L., Opposition to irresponsible global kidney exchange. Am. J. Transplant. 17, 2745–2746 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiseman A. C., Gill J. S., Financial incompatibility and paired kidney exchange: Walking a tightrope or blazing a trail? Am. J. Transplant. 17, 597–598 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ABC.es , La ONT frena la entrada en Europa de “una nueva forma de tráfico de órganos” propuesta por un nobel de Economía. https://www.abc.es/sociedad/abci-frena-entrada-europa-nueva-forma-trafico-organos-propuesta-nobel-economia-201804201139_noticia.html. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 32.Marino I. R., Roth A. E., Rees M. A., Doria C., Open dialogue between professionals with different opinions builds the best policy. Am. J. Transplant. 17, 2749 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roth A. E. et al., People should not be banned from transplantation only because of their country of origin. Am. J. Transplant. 17, 2747–2748 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roth A. E. et al., Global kidney exchange should expand wisely. Transpl. Int., 10.1111/tri.13656 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roth A., “Posts with label surrogacy.” Market Design (2020). https://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/search/label/surrogacy. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 36.Martinez M. R., Kennedy R., Spain to reject registration of babies born to surrogate mothers in Ukraine. Euronews, 20 February 2019. https://www.euronews.com/2019/02/20/spain-to-reject-registration-of-babies-born-to-surrogate-mothers-in-ukraine. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 37.Bundesgerichtshof, Rechtliche Mutterschaft der Leihmutter bei Anwendung deutschen Rechts, March 20, 2019. http://juris.bundesgerichtshof.de/cgi-bin/rechtsprechung/document.py?Gericht=bgh&Art=en&Datum=Aktuell&nr=94809&linked=pm&Blank=1. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 38.Wang V., Surrogate pregnancy battle pits progressives against feminists. NY Times, 12 June 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/12/nyregion/surrogate-pregnancy-law-ny.html. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- 39.Roth A., “Surrogacy finally becomes legal in New York.” Market Design (2020). https://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/2020/04/surrogacy-finally-becomes-legal-in-new.html. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 40.Roth A., “Posts with label prostitution.” Market Design (2020). http://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/search/label/prostitution. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 41.U.S.C. § 2423 - U.S. Code - Unannotated Title 18. Crimes and Criminal Procedure § 2423. Transportation of minors. https://codes.findlaw.com/us/title-18-crimes-and-criminal-procedure/18-usc-sect-2423.html. Accessed 21 July 2020.

- 42.Immordino G., Russo F. F., Laws and stigma: The case of prostitution. Eur. J. Law Econ. 40, 209–223 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jonsson S., Jakobsson N., Is buying sex morally wrong? Comparing attitudes toward prostitution using individual-level data across eight western European countries. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 61, 58–69 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotsadam A., Jakobsson N., Do laws affect attitudes? An assessment of the Norwegian prostitution law using longitudinal data. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 31, 103–115 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mullet E., Maria da Conceição P., Neto F., Mapping Brazilian and Portuguese young people’s positions towards highly paid sex work. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy, 1–14 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunningham S., Shah M., Decriminalizing indoor prostitution: Implications for sexual violence and public health. Rev. Econ. Stud. 85, 1683–1715 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Healy K., Krawiec K., Repugnance management and transactions in the body. Am. Econ. Rev. 107, 86–90 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen M., How decriminalizing sex work became a 2020 campaign issue. Mother Jones, 5 July 2019. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2019/07/how-decriminalizing-sex-work-became-a-2020-campaign-issue/. Accessed 3 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tin A., Democratic 2020 candidates struggle over whether to legalize sex work. CBS News, 13 July 2019. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/democratic-2020-candidates-struggle-over-whether-to-legalize-sex-work/. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- 50.115th Congress 2017–2018, Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act of 2017 (2017). https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1865. Accessed 21 July 2020.

- 51.Blanco S., Spain struggles with surrogate pregnancy issue. El Pais, 24 February 2017. https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2017/02/21/inenglish/1487696447_837759.html. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- 52.Blanco S., Spanish couples undergoing surrogacy processes left in legal limbo in Ukraine. El Pais, 31 August 2018. https://english.elpais.com/elpais/2018/08/30/inenglish/1535636353_685609.html. Accessed 14 July 2020.

- 53.Ro C., Why the global kidney exchange remains controversial. Forbes, 15 December 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinero/2019/12/15/why-the-global-kidney-exchange-remains-controversial/#757904845bcc. Accessed 3 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fricke A., Lebendspende breiter aufstellen. ÄrzteZeitung, 8 November 2019. https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Politik/Lebendspende-breiter-aufstellen-403402.html. Accessed 3 July 2020.

- 55.Yandle B., Bootleggers and baptists: The education of a regulatory economist. Regulation 7, 12–16 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devlin P., “The enforcement of morals” (Maccabaean lectures in jurisprudence) in Proceedings of the British Academy (The British Academy, 1959). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hart H. L. A., Law, Liberty, and Morality (Stanford University Press, 1963). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.