Abstract

Dental composites are routinely placed as part of tooth restoration procedures. The integrity of the restoration is constantly challenged by the metabolic activities of the oral microbiome. This activity directly contributes to a less-than-desirable half-life for the dental composite formulations currently in use. Therefore, many new antimicrobial dental composites are being developed to counteract the microbial challenge. To ensure that these materials will resist microbiome-derived degradation, the model systems used for testing antimicrobial activities should be relevant to the in vivo environment. Here, we summarize the key steps in oral microbial colonization that should be considered in clinically relevant model systems. Oral microbial colonization is a clearly defined developmental process that starts with the formation of the acquired salivary pellicle on the tooth surface, a conditioned film that provides the critical attachment sites for the initial colonizers. Further development includes the integration of additional species and the formation of a diverse, polymicrobial mature biofilm. Biofilm development is discussed in the context of dental composites, and recent research is highlighted regarding the effect of antimicrobial composites on the composition of the oral microbiome. Future challenges are addressed, including the potential of antimicrobial resistance development and how this could be counteracted by detailed studies of microbiome composition and gene expression on dental composites. Ultimately, progress in this area will require interdisciplinary approaches to effectively mitigate the inevitable challenges that arise as new experimental bioactive composites are evaluated for potential clinical efficacy. Success in this area could have the added benefit of inspiring other fields in medically relevant materials research, since microbial colonization of medical implants and devices is a ubiquitous problem in the field.

Keywords: oral biofilm, acquired enamel pellicle, Streptococcus mutans, dental materials, antimicrobial, material testing

Introduction

Oral microbiology and dental materials research face a common challenge: the oral biofilm. Oral microbiologists aim to understand how complex microbial interactions maintain biofilm homeostasis or cause dental diseases. Dental materials research aims to develop biocompatible materials that resist mechanical, chemical, and biological degradation, including exposure to chewing and grinding forces and contact with eukaryotic and microbial biofilm cells, saliva constituents, and foods and drinks. Currently, oral diseases are best described as problems of oral ecology, also referred to as dysbiosis (Kilian et al. 2016; Lamont et al. 2018), and innovative dental materials are being produced that possess antimicrobial and bioactive properties (Chen et al. 2018). Antimicrobial materials may function by killing bacteria or modifying bacterial virulence or via antifouling and biofilm disruption. Despite the progress made toward disease management and prevention, more strongly coordinated efforts between oral microbiologists and dental materials scientists could identify pitfalls and overcome roadblocks that may hinder or even invalidate research projects. Often out of practicality, dental materials testing frequently takes a reductionist approach, most suitable for the initial assessment of properties (Kreth et al. 2019). For example, antimicrobial activity is typically determined in vitro with single-species static biofilms. This approach is rapid and low cost and requires limited training. However, it should ideally be followed by assays that are more reflective of the oral environment and/or the dysbiotic nature of oral diseases and that systematically address critical spatial and temporal aspects of human oral biofilm development.

It is important to consider the long-term effects of materials upon the oral microbiome. Can sustained antimicrobial activity from dental materials be accomplished in an environment composed of highly adaptable organisms? This is pertinent for microorganisms that are known to encode or evolve antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. How can we integrate the knowledge of gene evolution to address challenges that arise after antimicrobial dental materials are in place for many years and experience degradation reactions that result in reduced longevity? Are broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities desirable in dental materials? Or should materials be designed to benefit commensal species associated with oral health or, conversely, to inhibit species associated with disease while sparing the commensal species? Can both outcomes be achieved simultaneously?

This review summarizes important considerations for an interdisciplinary approach to this topic, emphasizing the biology of microbial–dental material interactions. We focus on studies that outline novel approaches for the development and application of models to assess the interaction between the oral microbiome and dental composites. We also provide several recommendations for testing biomaterial-biofilm interactions (summarized in the Table).

Table.

Recommendations for Testing Biomaterial-Biofilm Interactions.

| Procedure | Comments |

|---|---|

| Biofilm inoculation and growth | |

| Inoculum concentration ~106 CFUs/mL | Supports the formation of microcolonies and relevant biofilm structures |

| Cells can progress through the genetic program of biofilm development | |

| Static biofilms | Highly reproducible |

| No special equipment required | |

| Flow cell biofilms | Flow rate of ~0.5 mL/min mimics normal salivary flow in the oral cavity |

| Planktonic cells are removed | |

| Possibility for controlled feeding cycles | |

| Development of more physiologically relevant biofilm architecture as compared with static biofilms | |

| Specialized equipment required, more labor intensive | |

| Growth mediuma | |

| Complex medium | Nutrient-rich medium that allows for the growth of a variety of fastidious microorganisms, including oral streptococci |

| Examples are brain-heart infusion, Todd Hewitt broth, Columbia broth | |

| Chemically defined medium | Fully characterized, reproducible chemical composition; can be used to test nutritional requirements |

| Artificial/human saliva | Clinically relevant; can be tailored to force nutritional interdependencies of mixed cultures of oral bacteria |

| For example, lactic acid produced by lactic acid bacteria can cross-feed Veillonella | |

| Salivary proteins can be used as nutritional source and AEP formation | |

| Surface standardization | |

| Saliva coating | AEP formation provides clinically relevant attachment sites for biofilm development and/or polymicrobial succession. |

| Environmental conditions | |

| Nutritional cycling | Replication of natural feast/famine cycles in the oral cavity |

| Mechanical challenge | Simulation of mastication effects by cyclic mechanical loading |

| Viability testing approachesb | |

| CFUs | “Gold standard” for viability testing |

| Requires efficient dispersal of biofilms into single cells | |

| Luciferase-based reporter assays | ATP-dependent luciferases (i.e., beetle luciferases) can be used to assay active bacterial metabolism. |

| Unlike most other reporter enzymes, luciferase has a high turnover rate at 37 °C (i.e., near real-time quantification) | |

| Exquisitely sensitive and simple assay with a dynamic range up to 8 orders of magnitude | |

| Requires genetically engineered bacterial strains | |

| Viability PCR | Sensitive; moderate preparation/assay time required |

| Able to assay individual species in multispecies biofilms | |

| Requires membrane-impermeable reagent propidium monoazide | |

| Quantitative RT-PCR based pre-rRNA analysis | Sensitive; extensive preparation/assay time required |

| Technique sensitive; requires more expertise | |

| Able to quantify any desired number of individual species in multispecies biofilms | |

| Requires RNA extraction and reverse transcription | |

| Species recommendation for biofilm modelsc | |

| Caries associated | Streptococcus mutans |

| Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus | |

| Actinomyces gerencseriae | |

| Scardovia wiggsiae | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | |

| Endodontic associated | Enterococcus faecalis |

| Actinomyces odontolyticus, Actinomyces naeslundii | |

| Parvimonas micra | |

| Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens | |

| Periodontitis associated | Fusobacterium nucleatum |

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | |

| P. intermedia, P. nigrescens | |

| Tannerella forsythia | |

| Filifactor alocis | |

| Peri-implantitis associated | A. actinomycetemcomitans |

| P. gingivalis | |

| P. intermedia, P. nigrescens | |

| T. forsythia | |

| P. micra | |

| Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus haemolyticus | |

AEP, acquired enamel pellicle; CFU, colony-forming unit; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Growth media might interact with dental composite biomaterials regardless of microbial presence.

Viability testing needs to be optimized for the selected species used for testing of biomaterial-biofilm interactions.

This nonexhaustive list should be used as guidance; it contains examples of species most commonly associated with each disease condition.

Biofilm Formation on Dental Enamel versus Dental Composites

Dental biofilm formation is one of the best-studied bacterial developmental processes (Kreth and Herzberg 2015). Individual steps leading to the spatial and temporal arrangement of the biofilm can be clearly separated (Fig. 1). We briefly summarize the individual steps and discuss how they can be integrated into dental materials research.

Figure 1.

Developmental steps of acquired enamel pellicle (AEP) and biofilm formation. The AEP consists of adsorbed salivary proteins and other macromolecules (depicted as blue, yellow, and orange aggregates) that provide attachment sites used by early colonizers via specific bacterial surface receptors or adhesins (shown in red). The initial attachment of the early colonizers is the first step toward biofilm formation, which is a developmental process that consists of several stages. During the attachment stage, early colonizing species attach to the AEP on the tooth enamel via adhesins. Secondary and late colonizers will coaggregate/coadhere by using surface receptors present on other species in the community. For the maturation stage, bacteria communicate metabolically through the release of small molecules and substrates for cross-feeding. Antimicrobial components such as H2O2 and bacteriocins are also produced, triggering interspecies growth competition. Additionally, genetic information is exchanged via the release of extracellular DNA, which also plays a structural role in the biofilm. Green circles represent early colonizers; orange circles and blue rods, secondary colonizers; purple rods, fusobacteria; white circles, yellow and red rods are late colonizers. In the third and fourth panels, the gray regions represent the exopolysaccharide matrix (EPS).

Microbe-Acquired Pellicle Interactions during Dental Biofilm Formation

Upon saliva exposure, the tooth is rapidly coated with a saliva-derived film called the acquired enamel pellicle (AEP; Fig. 1; Kreth and Herzberg 2015). Among other functions, the AEP serves mainly as a lubricant that protects tooth enamel against abrasion, attrition, erosion, and dental caries (Dawes et al. 2015). The AEP influences the composition, structure, and function of the developing biofilm. Its formation is an integral part of oral biofilm initiation, since bacteria and bacteria-derived enzymes are integrated into the pellicle, blurring the lines between the physiologically distinct mechanisms of AEP and biofilm formation (Siqueira et al. 2012). AEP formation is a dynamic and structured process involving a sequential integration of proteins, glycoproteins, and saliva-derived biopolymers that lead to a mature film having distinct biophysical properties. Consequently, a newly formed AEP is distinct from an aged AEP (Guth-Thiel et al. 2019) and shows interindividual and site-specific differences (Delius et al. 2017; Guth-Thiel et al. 2019). The thickness of the AEP on enamel ranges between 20 and 700 nm after a 2-h maturation period, depending on the intraoral location, but could increase to 1,300 nm after 24 h (Hannig 1999). The AEP ultrastructure is initially heterogeneous, including areas covered by protein aggregates with free space in between that becomes covered by the liquid or gel phase (Siqueira et al. 2012). This fact should be considered during dental materials testing since 1) the AEP alters surface properties and 2) the AEP is formed as a preconditioning process and might not form appropriately if test materials and bacteria are added simultaneously in an in vitro experiment.

Salivary proteins and glycoproteins contained in the AEP can serve as major sources of nutrients, as well as docking molecules for pioneer colonizing bacteria (Jakubovics 2015). Pioneer colonizers determine the successive integration of later colonizing species into the developing biofilm through the display of lectin-like docking molecules on their surfaces, which makes AEP protein deposition crucial for normal spatial and temporal biofilm development (Jakubovics 2015; Kreth and Herzberg 2015). While many oral bacterial species may adhere to AEP-coated surfaces to varying extents, for some bacteria this may rarely occur in vivo because they rely on coaggregation. All of these factors should be considered in developing clinically relevant testing models.

One of the most abundant proteins in AEP is alpha-amylase, which catalyzes starch hydrolysis (Boehlke et al. 2015). The ability to directly bind to amylase is conserved among streptococci, which are important early colonizers. Moreover, divalent salivary cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+, present in concentrations >1 mM in healthy individuals (Gradinaru et al. 2007), play an important role in streptococcal AEP binding. Chelation of both cations decreases streptococcal binding to several salivary and AEP components (Deng et al. 2014). Thus, the biological environment will influence binding and community selection of the oral biofilm, and alpha-amylase and these cations should be present in physiologic concentrations in any biofilm experiment evaluating AEP-coated dental materials.

The microbial succession of bacterial species on dental materials is far less understood than AEP formation, mainly because single-species biofilms are typically employed to evaluate attachment to dental materials (Hao et al. 2018). A recent in vivo study with removable splints containing different dental materials did not show significant differences in the associated microbiota. However, the salivary pellicle that formed on the various materials showed a similar composition, suggesting that the AEP is the principal determinant for microbial colonization and succession on dental materials (Mukai et al. 2020). Although the available data suggest that microbial succession on dental materials is similar to that on sound enamel, differences in the abundance of relevant species may still exist. This was demonstrated in an in vivo study comparing oral biofilm formation on dental composites containing higher versus lower ester-linkages, with a greater abundance of Streptococcus mutans on the former (Kusuma Yulianto et al. 2019). Certainly, further research is needed to better characterize biofilm formation, microbial succession, and species abundance on dental materials.

Modifications of Dental Composites and How They Influence Biofilm Formation

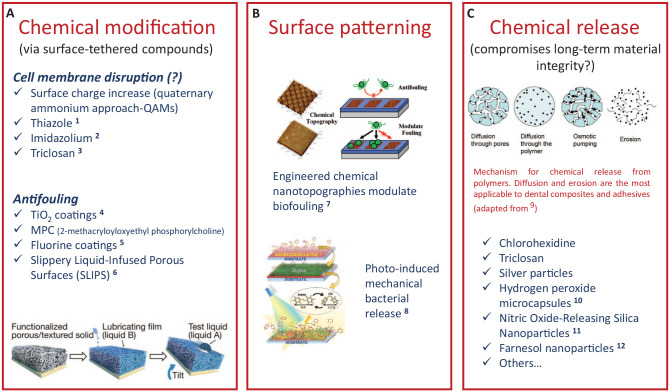

A common strategy for the development of antimicrobial/antifouling dental materials includes surface property modification. These include topography (texturing or micropatterning), hydrophilicity modulation, or functionalization with components that serve as protein repellents to deter AEP adhesion or that disrupt cell membrane integrity, including quaternary ammonium and other broad-spectrum antibiotic compounds (Fig. 2A; Koo et al. 2017). Quaternary ammonium methacrylates (QAMs) are the most studied charged species for antimicrobial applications (Imazato et al. 1994; Zhou et al. 2016). Others include polymerizable antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin (Zhang et al. 2018), imidazole (Hwang et al. 2017), and other synthetic and natural compounds (Pereira-Cenci et al. 2009). The advantage of this approach is that the material is copolymerized with the resin matrix and not released into the environment (Hwang et al. 2017; Jiang et al. 2017), therefore theoretically providing a long-term effect. The antimicrobial activity has been shown to be local and contact dependent (Hwang et al. 2017; Jiang et al. 2017). It is noteworthy that there are potential deleterious effects on the bulk mechanical properties of composites with such modifications (Cheng et al. 2012).

Figure 2.

Examples of strategies for material composition modifications toward the design of antibiofilm dental materials. (A) The chemical modification of the surface can be accomplished by tethering several antifouling, antibiotic, or targeted antibiofilm compounds. Several compounds have been made copolymerizable with the composite/adhesive organic matrix by the addition of methacrylate moieties to the molecule. The design of superhydrophilic or superhydrophobic surfaces has also shown promise as antimicrobial solutions in marine and biomedical applications, for example. (B) The topography plays a role in cell attachment and can be harnessed to modulate biofouling. This is accomplished via micropatterning or stimulus-responsive modifications, such as the photoresponsive example shown here. (C) The direct release of chemicals may disrupt material integrity upon release. Chemical-releasing materials are created by passively adding chemicals to the original composition or by the design of carriers for drug delivery. QAM, quaternary ammonium methacrylate. 1Luo et al. (2015). 2Hwang et al. (2017). 3Wu et al. (2015). 4Kuroiwa et al. (2018). 5Zhang et al. (2013). 6Epstein et al. (2012). 7Kuliasha et al. (2020). 8Kehe et al. (2019). 9Fredenberg et al. (2011). 10Mallepally et al. (2014). 11Slomberg et al. (2013). 12Sims et al. (2018).

One fact that often is neglected is that any surface characteristic can easily be masked by an AEP layer and the bacteria that adhere to the AEP. For QAMs, the specific antimicrobial mechanism is not well understood, though it is plausible that the positive quaternary nitrogen charge interaction with the microbial cell wall causes disruption to its integrity (Jiang et al. 2017). The charge localization is important and is influenced by the size of the side chain (Zhang et al. 2016), though due to steric constraints, it is questionable whether the side chain can physically disrupt the membrane as hypothesized (Zhou et al. 2016). An alternative hypothesis is that the influence of the side chain on the efficacy of charged QAMs is related to pseudo-micelle formation occurring via phase separation during polymerization (Zhao and Yu 2017). Regardless, the electrostatic force and any contact-dependent killing effect would need to be extended over a certain range to be effective at the AEP-bacterial interface. Thus, it is likely that a >20-nm AEP layer, even nonuniformly distributed on a material surface, interferes with contact-dependent bioactivity (Muller et al. 2009). At least one study showed an AEP-dependent effect that overestimated the activity of the QAMs when the AEP was not considered (Li, Weir, et al. 2014).

Another inherent problem of contact-dependent antimicrobial restoratives is that a layer of dead or compromised bacteria will be left behind, which would likely continue to serve as a suitable attachment site to initiate colonization by subsequent waves of bacteria that never come into direct contact with the antimicrobial surface of the material. In this case, biofilm development might proceed normally with the production of the extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) matrix and further maturation, including interspecies interactions (communication, genetic exchange, cross-feeding) and antagonism (H2O2 and bacteriocin production), just as it would on sound enamel (Kreth and Herzberg 2015; Fig. 1). The same issue of interfering with effectiveness holds true for antimicrobial activity that is caused by diffusion of released antimicrobial compounds, such as chlorhexidine or triclosan, another strategy proposed to improve dental composites (Zhang et al. 2014; Fig. 2A, C). Interference of diffusion through the AEP layer and sequestration of the antimicrobial compound(s) with AEP proteins are plausible, potentially limiting the effectiveness of such a strategy.

Interestingly, the presence of saliva might augment caries development in a secondary caries model containing S. mutans monospecies biofilms (Hetrodt et al. 2018). The addition of 30% native autoclaved saliva in the presence of 0.5% sucrose caused a significant increase in the size of demineralized lesions in the gaps between the composite restorations and tooth enamel. While the mechanism has not been determined, it was speculated that the AEP supported an increased attachment of S. mutans to the composite, while the saliva provided a more favorable nutritional environment (Hetrodt et al. 2018). However, a confounding variable in the study is the fact that the saliva was autoclaved and likely denatured most salivary proteins. In any case, it is highly recommended that bioactive materials be assessed in the presence of an AEP and saliva, as both may affect bioactivity. Such data are currently lacking, as are enhanced in vitro models that better simulate the clinical situation.

The study by Li and colleagues (Li, Weir, et al. 2014) also raises an important issue relevant to any testing environment. For example, medium composition can strongly bias the ecologic in vitro profile of mixed-species biofilms, as well as the complexity and final biomass of the test community. When the 24-h growth of plaque-derived static microcosms was compared in 2 media, BMM (basal medium with mucin) resulted in 2-fold increases in biofilm biomass as compared with DMM (defined medium with mucin). Longer incubation (up to 10 d) equalized any biomass differences. But importantly, the 2 media resulted in distinct bacterial species compositions that were also quite different from the original inoculum composition (Filoche et al. 2007). A more recent study confirmed that the choice of growth medium is the principal factor affecting microbial community composition (Li et al. 2017). It is also noteworthy that the enzyme activity profile of the biofilm community is similarly significantly influenced by the selected growth medium (Wong and Sissons 2001). For certain applications, such as studies of methacrylate resin biodegradation from esterases or bacterial biofilms (Nedeljkovic et al. 2017; Huang, Siqueira, et al. 2018), vastly different C4-esterase activities have been observed in BMM versus DMM (Wong and Sissons 2001). In this case, one might obtain highly disparate levels of resin degradation depending on the growth medium. Therefore, one must be cognizant that the choice of growth medium can produce a biofilm that is quite distinct in composition and/or metabolism from that of dental plaque.

Finally, the role of surface topography cannot be neglected. Several studies have shown that texturing or micropatterning of the surface can modulate cell attachment (Kuliasha et al. 2020; Fig. 2B). Hydrophobic surfaces with microscopic air pockets inhibit the interaction of microbes with the surface (Decker et al. 2013). Also, photoreversible surfaces, from which bacteria can be mechanically removed via the photoinduced isomerization of azobenzene, demonstrate antifouling properties (Kehe et al. 2019). Modifications of the composite surface topography, as well as degradation of the adhesive interface, may also be observed in response to the interactions with bacteria (Li, Carrera, et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2018). Surface roughness increases over time for composites exposed to acidic solutions (Briso et al. 2011) or S. mutans biofilms (Hyun et al. 2015). Both those observations are likely linked to direct hydrolysis of the resin and leaching of unreacted components (Delaviz et al. 2014) but may also derive from enzymatic activity (Serkies et al. 2016; Huang, Sadeghinejad, et al. 2018). Biofilm growth may be facilitated by the increased roughness (Beyth et al. 2008), which would essentially provide a feedback loop for continued surface degradation. Previous studies showed variable results regarding the effect of surface roughness of dental composites upon biofilm formation (Hyun et al. 2015; Park et al. 2019). A recent systematic review (Dutra et al. 2018) suggested that the concept of a threshold surface roughness for biofilm formation on dental composites is not well supported by the literature. The increased proliferation on the surface of the composite also increases the risk for degradation of the adhesive interface (Li, Carrera, et al. 2014). Since those 2 components are essentially derived from the same chemistry in the majority of commercially available materials, the degradation mechanisms mentioned earlier may also contribute to gap formation at the restorative interface. All these factors should be considered when designing new materials and testing procedures.

Next Steps: Surface-Attached Growth of the Community

The AEP determines the sequence of bacterial attachment and the architecture of the dental biofilm (Lendenmann et al. 2000). The initial process of biofilm formation includes reversible attachment of bacterial surface proteins to AEP receptors, leading to a genetically controlled developmental process that encompasses the production of EPS and is followed by biofilm growth, maturation, and dispersal (Fig. 1; Kreth and Herzberg 2015). The environment is a major modulator of this developmental process. For example, gene expression within biofilms can be heavily influenced by neighboring species, nutritional availability, and salivary flow rate as well as the chemistry of dental materials (Shemesh et al. 2010). A recent microbiome study of 14 volunteers found only modest changes in the microbial community profiles formed on 2 composite materials (Conrads et al. 2019). The main difference appears to be the abundance of certain microbial species, rather than their presence or absence. The authors also observed a strong correlation between the composition of the in vivo dental material microbiome and an in vitro saliva-derived biofilm model (Conrads et al. 2019). Given the dearth of such studies, it is currently unclear whether similar results would be obtained with different commercially available materials. Likewise, it remains to be determined to what extent growth on dental materials affects the overall transcriptional and/or metabolic landscape of microbiome communities.

How Dental Composites Influence the Dental Biofilm

Dental composites have been shown to mainly influence biofilm composition, gene expression (transcriptomics), and protein production (proteomics), but the influence on gene expression and proteomics has been well documented only for S. mutans (Sadeghinejad et al. 2017). Further investigations are required with multispecies or microcosm biofilms. Ideally, in vivo systems will more definitively explain changes in virulence gene expression or, alternatively, expression of genes that could favor commensal species and thus exclude species that are associated with caries.

Initial Effects on Biofilm Composition

In addition to the effects of surface roughness on bacterial attachment and proliferation, in vitro evidence suggests that the formulations of antimicrobial dental composites can influence biofilm community composition. This was evident in a study using modified acrylic dental resins incorporating different concentrations of antimicrobial silver vanadate and saliva-derived biofilms and saliva as growth medium (de Castro et al. 2018). The compositional shift was most apparent after a 7-d incubation period with a decrease in certain species belonging to the Bacteroidetes phylum (mainly Prevotella and Porphyromonas; de Castro et al. 2018). Concurrently, other phyla increased in abundance, suggesting that antimicrobial activities might enrich or inhibit particular bacterial phyla, presumably through a complex combination of direct and indirect effects of the antimicrobial. This observation also illustrates existing limitations of single-species biofilm models for materials testing. While a single species might be readily inhibited in vitro by a given antimicrobial composite, this susceptibility is often quite different in a multispecies setting. Alternatively, antimicrobial activities may bias the in vivo community composition toward one that is detrimental to the material or even the surrounding healthy tissue. For example, the antimicrobial compound carolacton was reported to induce membrane damage and cell death of S. mutans at low pH (Kunze et al. 2010), which theoretically makes it an ideal antimicrobial for the prevention of secondary caries. However, 2 recent studies found that carolacton was unable to prevent secondary caries development (Hetrodt et al. 2019) or even affect the microbial composition of in vitro saliva-derived multispecies biofilms (Conrads et al. 2019). It was speculated that the poor performance of carolacton in a diverse polymicrobial setting could be due to its biodegradation, sequestration by the EPS, or other resistance mechanisms that may function (Conrads et al. 2019; Hetrodt et al. 2019). It would not be surprising to discover that many other potential antimicrobial additives are equally ineffective against polymicrobial biofilms, as these communities have evolved to persist in the presence of the countless host- and microbiome-derived oral environmental stressors. Similarly, polymicrobial biofilms in general are increasingly recognized as having greatly enhanced resistance to many antibiotics relative to their single-species counterparts (Orazi and O’Toole 2019).

Looking into the Future: How Dental Composites May Change Bacterial Behavior after Long-term Intraoral Exposure

Although numerous properties of dental materials are tested in the laboratory setting, a notable exception is the long-term effect of dental materials upon the behavior of oral bacteria. Most microbes are amazingly adaptable, especially when chronically challenged by a particular stressor (Soucy et al. 2015). There are several reasons for this, one being horizontal genetic exchange (Roberts and Kreth 2014). It has been shown that numerous dental biofilm bacteria, especially the oral streptococci, are able to develop a physiologic state called competence that enables the active uptake of extracellular DNA (Fontaine et al. 2015). This developmental state is strongly induced under biofilm growth conditions and allows, among other things, for the exchange of antibiotic resistance genes (Madsen et al. 2012). Given the trend toward developing dental materials with antimicrobial or antifouling activity, it is surprising that the development of resistance mechanisms is seldom addressed (Cieplik et al. 2019). Since biofilms formed on sound enamel are often contiguous with those formed on restorations, there are ample opportunities for resistance mechanisms to develop over the long term and spread to other bacteria. Environmental stress is a classic trigger for horizontal gene transfer mechanisms as well as active mutagenesis of bacterial chromosomes (Fitzgerald and Rosenberg 2019; Ram and Hadany 2019). Accordingly, in vitro studies with S. mutans biofilms have demonstrated how exposure to toxic biodegradation products of triethylene glycol dimethacrylate can induce the expression of natural competence genes relevant for horizontal gene transfer (Sadeghinejad et al. 2016).

Another bacterial antimicrobial evasion strategy is the development of persister cells, a metabolically inactive (i.e., dormant) subpopulation found in biofilm and planktonic cultures. QAMs, for example, cannot prevent persister cell formation in S. mutans (Wang et al. 2017). Once reactivated, the persister cells show increased expression of gtf genes responsible for the production of the EPS (Jiang et al. 2017), which has potential implications for future QAM susceptibility and caries development. This study highlights the importance of the potential long-term effects arising from chronic exposure to bioactive materials.

How to Determine Antimicrobial Activity?

Given the widespread interest in the development of antimicrobial resins, it is important to ask whether a practical experimental model can be developed to provide a relevant biofilm environment. For example, exposing dental materials to oral bacteria in vivo with removable appliances should provide the most clinically relevant assay system. Even with this approach, a multitude of variables could bias experimental outcomes, including the chemistry and architecture of the appliance itself (Jokstad 2016; Ferracane 2017). For antimicrobial materials, it is particularly important to select an appropriate approach to assess inhibitory activities. Several methods are available to determine bacterial viability, including the gold standard colony-forming units determination, viability polymerase chain reaction with membrane-impermeable reagent propidium monoazide (Cenciarini-Borde et al. 2009), and luciferase-based testing (Esteban Florez et al. 2020), and each has specific strengths and weaknesses (Lin 2017; Kreth et al. 2019; Table). Metabolic activity testing is a common approach that is suitable for many applications. However, an agent triggering reduced metabolic activity could yield misleading results. For the oral commensal species Streptococcus sanguinis, sublethal concentrations of ampicillin, an antibiotic that targets the cell wall, causes a transition to slower growth and reduced metabolism, but the cells remain viable (El-Rami et al. 2018). Furthermore, persister cells and viable but nonculturable cells would likely be missed in metabolic assays but might still be capable of expressing certain virulence properties (Ramamurthy et al. 2014). Fortunately, these subpopulations of cells typically comprise only small fractions of the total population, but as described previously, they can repopulate a depleted community with potentially new traits or behaviors. Critical limitations have also been identified with commonly used fluorescent bacterial viability dyes, such as the BacLight LIVE/DEAD stain. Such dyes are a convenient indicator of the overall health of biofilms but require further independent evaluation before any conclusion can be drawn about bacterial viability (Netuschil et al. 2014; Kreth et al. 2019). Ideally, bacterial viability assessments should be performed through more than 1 technique (van de Lagemaat et al. 2017). It is worth noting that a determination of colony-forming units via dilution plating remains the gold standard.

Outlook and Conclusion

The interdisciplinary effort to integrate microbial biofilm studies into dental materials research is an area that has seen rapid development in the past decade, but key deficiencies remain. We are still lacking considerable knowledge about the influence of dental material composition upon the ecology of the oral microbiome. Likewise, there is a very cursory understanding of the effect of dental material chemistry upon the transcriptional responses of the microbiome. These are important areas of inquiry if we hope to understand and predict the future clinical efficacy of novel materials. Others have begun to address this issue, which is certainly encouraging (Catto et al. 2018; Catto and Cappitelli 2019). The Table provides a summary of the important variables to consider when designing experiments to address these critical questions.

Another emerging area of interest that may predict future clinical efficacy is related to the mechanical properties of biofilms. Through largely uncharacterized mechanisms, various types of environmental stress have been shown to trigger bacteria to structurally remodel biofilms into more rigid architectures that are difficult to remove and are more resistant to stress (Boudarel et al. 2018; Marx et al. 2020). Could such mechanisms explain why certain antimicrobial additives are not as effective as predicted? Ultimately, it is hoped that a greater awareness of some of these issues will lead to even more productive interdisciplinary collaborations between materials scientists and microbiologists to develop the next generation of smarter bioactive materials. Perhaps a reasonable starting point is to develop greater standardization of the protocols used to explore the dental composite–oral biofilm interface, such as the presence of a flowing media environment, the application of mechanical loading to impose clinically relevant stress conditions, and the use of validated multispecies biofilm models. All of these may help to rapidly advance the field with even greater impact.

Author Contributions

J. Kreth, J. Merritt, C.S. Pfeifer, S. Khajotia, J.L. Ferracane, contributed to conception and design, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nyssa Cullin for partial help with Figure 1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

The authors acknowledge the following National Institutes of Health grants: R56-DE021726 (J.K.), R01-DE029492 (J.K.), U01-DE023756 (C.S.P., J.L.F.), R01-DE026113 (C.S.P., J.L.F., and J.M.), K02-DE025280 (C.S.P.), R01-DE028757 (C.S.P.), R35-DE029083 (C.S.P.), R15DE028448 (S.K.), and R35-DE 028252 (J.M.).

ORCID iD: J. Kreth  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8599-8310

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8599-8310

References

- Beyth N, Bahir R, Matalon S, Domb AJ, Weiss EI. 2008. Streptococcus mutans biofilm changes surface-topography of resin composites. Dent Mater. 24(6):732–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehlke C, Zierau O, Hannig C. 2015. Salivary amylase—the enzyme of unspecialized euryphagous animals. Arch Oral Biol. 60(8):1162–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudarel H, Mathias JD, Blaysat B, Grediac M. 2018. Towards standardized mechanical characterization of microbial biofilms: analysis and critical review. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 4:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briso AL, Caruzo LP, Guedes AP, Catelan A, dos Santos PH. 2011. In vitro evaluation of surface roughness and microhardness of restorative materials submitted to erosive challenges. Oper Dent. 36(4):397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catto C, Cappitelli F. 2019. Testing anti-biofilm polymeric surfaces: where to start? Int J Mol Sci. 20(15):E3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catto C, Villa F, Cappitelli F. 2018. Recent progress in bio-inspired biofilm-resistant polymeric surfaces. Crit Rev Microbiol. 44(5):633–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarini-Borde C, Courtois S, La Scola B. 2009. Nucleic acids as viability markers for bacteria detection using molecular tools. Future Microbiol. 4(1):45–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Suh BI, Yang J. 2018. Antibacterial dental restorative materials: a review. Am J Dent. 31:6B–12B. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Weir MD, Zhang K, Xu SM, Chen Q, Zhou X, Xu HH. 2012. Antibacterial nanocomposite with calcium phosphate and quaternary ammonium. J Dent Res. 91(5):460–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieplik F, Jakubovics NS, Buchalla W, Maisch T, Hellwig E, Al-Ahmad A. 2019. Resistance toward chlorhexidine in oral bacteria—is there cause for concern? Front Microbiol. 10:587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrads G, Wendt LK, Hetrodt F, Deng ZL, Pieper D, Abdelbary MMH, Barg A, Wagner-Dobler I, Apel C. 2019. Deep sequencing of biofilm microbiomes on dental composite materials. J Oral Microbiol. 11(1):1617013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes C, Pedersen AM, Villa A, Ekstrom J, Proctor GB, Vissink A, Aframian D, McGowan R, Aliko A, Narayana N, et al. 2015. The functions of human saliva: a review sponsored by the World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI. Arch Oral Biol. 60(6):863–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro DT, do Nascimento C, Alves OL, de Souza Santos E, Agnelli JAM, Dos Reis AC. 2018. Analysis of the oral microbiome on the surface of modified dental polymers. Arch Oral Biol. 93:107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker JT, Kirschner CM, Long CJ, Finlay JA, Callow ME, Callow JA, Brennan AB. 2013. Engineered antifouling microtopographies: an energetic model that predicts cell attachment. Langmuir. 29(42):13023–13030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaviz Y, Finer Y, Santerre JP. 2014. Biodegradation of resin composites and adhesives by oral bacteria and saliva: a rationale for new material designs that consider the clinical environment and treatment challenges. Dent Mater. 30(1):16–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delius J, Trautmann S, Medard G, Kuster B, Hannig M, Hofmann T. 2017. Label-free quantitative proteome analysis of the surface-bound salivary pellicle. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 152:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Bensing BA, Thamadilok S, Yu H, Lau K, Chen X, Ruhl S, Sullam PM, Varki A. 2014. Oral streptococci utilize a Siglec-like domain of serine-rich repeat adhesins to preferentially target platelet sialoglycans in human blood. PLoS Pathog. 10(12):e1004540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra D, Pereira G, Kantorski KZ, Valandro LF, Zanatta FB. 2018. Does finishing and polishing of restorative materials affect bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation? A systematic review. Oper Dent. 43(1):E37–E52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rami F, Kong X, Parikh H, Zhu B, Stone V, Kitten T, Xu P. 2018. Analysis of essential gene dynamics under antibiotic stress in Streptococcus sanguinis. Microbiology. 164(2):173–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AK, Wong TS, Belisle RA, Boggs EM, Aizenberg J. 2012. Liquid-infused structured surfaces with exceptional anti-biofouling performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(33):13182–13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban Florez FL, Hiers RD, Zhao Y, Merritt J, Rondinone AJ, Khajotia SS. 2020. Optimization of a real-time high-throughput assay for assessment of Streptococcus mutans metabolism and screening of antibacterial dental adhesives. Dent Mater. 36(3):353–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferracane JL. 2017. Models of caries formation around dental composite restorations. J Dent Res. 96(4):364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filoche SK, Soma KJ, Sissons CH. 2007. Caries-related plaque microcosm biofilms developed in microplates. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 22(2):73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald DM, Rosenberg SM. 2019. What is mutation? A chapter in the series: how microbes “jeopardize” the modern synthesis. PLoS Genet. 15(4):e1007995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine L, Wahl A, Flechard M, Mignolet J, Hols P. 2015. Regulation of competence for natural transformation in streptococci. Infect Genet Evol. 33:343–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredenberg S, Wahlgren M, Reslow M, Axelsson A. 2011. The mechanisms of drug release in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based drug delivery systems—a review. Int J Pharm. 415(1–2):34–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru I, Ghiciuc CM, Popescu E, Nechifor C, Mandreci I, Nechifor M. 2007. Blood plasma and saliva levels of magnesium and other bivalent cations in patients with parotid gland tumors. Magnes Res. 20(4):254–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth-Thiel S, Kraus-Kuleszka I, Mantz H, Hoth-Hannig W, Hahl H, Dudek J, Jacobs K, Hannig M. 2019. Comprehensive measurements of salivary pellicle thickness formed at different intraoral sites on Si wafers and bovine enamel. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 174:246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannig M. 1999. Ultrastructural investigation of pellicle morphogenesis at two different intraoral sites during a 24-h period. Clin Oral Investig. 3(2):88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Huang X, Zhou X, Li M, Ren B, Peng X, Cheng L. 2018. Influence of dental prosthesis and restorative materials interface on oral biofilms. Int J Mol Sci. 19(10):E3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrodt F, Lausch J, Meyer-Lueckel H, Apel C, Conrads G. 2018. Natural saliva as an adjuvant in a secondary caries model based on Streptococcus mutans. Arch Oral Biol. 90:138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrodt F, Lausch J, Meyer-Lueckel H, Conrads G, Apel C. 2019. Evaluation of restorative materials containing preventive additives in a secondary caries model in vitro. Caries Res. 53(4):447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Sadeghinejad L, Adebayo OIA, Ma D, Xiao Y, Siqueira WL, Cvitkovitch DG, Finer Y. 2018. Gene expression and protein synthesis of esterase from Streptococcus mutans are affected by biodegradation by-product from methacrylate resin composites and adhesives. Acta Biomaterialia. 81:158–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Siqueira WL, Cvitkovitch DG, Finer Y. 2018. Esterase from a cariogenic bacterium hydrolyzes dental resins. Acta Biomater. 71:330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang G, Koltisko B, Jin X, Koo H. 2017. Nonleachable imidazolium-incorporated composite for disruption of bacterial clustering, exopolysaccharide-matrix assembly, and enhanced biofilm removal. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 9(44):38270–38280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun HK, Salehi S, Ferracane JL. 2015. Biofilm formation affects surface properties of novel bioactive glass-containing composites. Dent Mater. 31(12):1599–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imazato S, Torii M, Tsuchitani Y, McCabe JF, Russell RR. 1994. Incorporation of bacterial inhibitor into resin composite. J Dent Res. 73(8):1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubovics NS. 2015. Saliva as the sole nutritional source in the development of multispecies communities in dental plaque. Microbiol Spectr. 3(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Qiu W, Zhou X, Li H, Lu J, Xu HH, Peng X, Li M, Feng M, Cheng L, et al. 2017. Quaternary ammonium-induced multidrug tolerant Streptococcus mutans persisters elevate cariogenic virulence in vitro. Int J Oral Sci. 9(e7):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokstad A. 2016. Secondary caries and microleakage. Dent Mater. 32(1):11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehe GM, Mori DI, Schurr MJ, Nair DP. 2019. Optically responsive, smart anti-bacterial coatings via the photofluidization of azobenzenes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 11(2):1760–1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilian M, Chapple IL, Hannig M, Marsh PD, Meuric V, Pedersen AM, Tonetti MS, Wade WG, Zaura E. 2016. The oral microbiome—an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br Dent J. 221(10):657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo H, Allan RN, Howlin RP, Stoodley P, Hall-Stoodley L. 2017. Targeting microbial biofilms: current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 15(12):740–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreth J, Ferracane JL, Pfeifer CS, Khajotia S, Merritt J. 2019. At the interface of materials and microbiology: a call for the development of standardized approaches to assay biomaterial-biofilm interactions. J Dent Res. 98(8):850–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreth J, Herzberg MC. 2015. Molecular principles of adhesion and biofilm formation. In: Chávez de Paz LE, Sedgley CM, Kishen A, editors. The root canal biofilm. Berlin (Germany): Springer; p. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kuliasha CA, Fedderwitz RL, Finlay JA, Franco SC, Clare AS, Brennan AB. 2020. Engineered chemical nanotopographies: reversible addition-fragmentation chain-transfer mediated grafting of anisotropic poly(acrylamide) patterns on poly(dimethylsiloxane) to modulate marine biofouling. Langmuir. 36(1):379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze B, Reck M, Dotsch A, Lemme A, Schummer D, Irschik H, Steinmetz H, Wagner-Dobler I. 2010. Damage of Streptococcus mutans biofilms by carolacton, a secondary metabolite from the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum. BMC Microbiol. 10:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa A, Nomura Y, Ochiai T, Sudo T, Nomoto R, Hayakawa T, Kanzaki H, Nakamura Y, Hanada N. 2018. Antibacterial, hydrophilic effect and mechanical properties of orthodontic resin coated with UV-responsive photocatalyst. Materials (Basel). 11(6):E889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma Yulianto HD, Rinastiti M, Cune MS, de Haan-Visser W, Atema-Smit J, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC. 2019. Biofilm composition and composite degradation during intra-oral wear. Dent Mater. 35(5):740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Koo H, Hajishengallis G. 2018. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 16(12):745–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendenmann U, Grogan J, Oppenheim FG. 2000. Saliva and dental pellicle—a review. Adv Dent Res. 14:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Zhou X, Zhou X, Wu P, Li M, Feng M, Peng X, Ren B, Cheng L. 2017. Effects of different substrates/growth media on microbial community of saliva-derived biofilm. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 364(13). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Weir MD, Fouad AF, Xu HH. 2014. Effect of salivary pellicle on antibacterial activity of novel antibacterial dental adhesives using a dental plaque microcosm biofilm model. Dent Mater. 30(2):182–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Carrera C, Chen R, Li J, Lenton P, Rudney JD, Jones RS, Aparicio C, Fok A. 2014. Degradation in the dentin-composite interface subjected to multi-species biofilm challenges. Acta Biomater. 10(1):375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin NJ. 2017. Biofilm over teeth and restorations: what do we need to know? Dent Mater. 33(6):667–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Huang Q, Liu F, Lin Z, He J. 2015. Synthesis of antibacterial methacrylate monomer derived from thiazole and its application in dental resin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 49:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen JS, Burmolle M, Hansen LH, Sorensen SJ. 2012. The interconnection between biofilm formation and horizontal gene transfer. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 65(2):183–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallepally RR, Parrish CC, M Hugh MAM, Ward KR. 2014. Hydrogen peroxide filled poly(methyl methacrylate) microcapsules: potential oxygen delivery materials. Int J Pharm; 475(1):130–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx P, Sang Y, Qin H, Wang Q, Guo R, Pfeifer C, Kreth J, Merritt J. 2020. Environmental stress perception activates structural remodeling of extant Streptococcus mutans biofilms. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 6(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai Y, Torii M, Urushibara Y, Kawai T, Takahashi Y, Nobuko M, Ohkubo C, Ohshima T. 2020. Analysis of plaque microbiota and salivary proteins adhering to dental materials. J Oral Biosci. 62(2):182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R, Eidt A, Hiller KA, Katzur V, Subat M, Schweikl H, Imazato S, Ruhl S, Schmalz G. 2009. Influences of protein films on antibacterial or bacteria-repellent surface coatings in a model system using silicon wafers. Biomaterials. 30(28):4921–4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedeljkovic I, De Munck J, Ungureanu AA, Slomka V, Bartic C, Vananroye A, Clasen C, Teughels W, Van Meerbeek B, Van Landuyt KL. 2017. Biofilm-induced changes to the composite surface. J Dent. 63:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netuschil L, Auschill TM, Sculean A, Arweiler NB. 2014. Confusion over live/dead stainings for the detection of vital microorganisms in oral biofilms—which stain is suitable? BMC Oral Health. 14:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orazi G, O’Toole GA. 2019. “It takes a village”: mechanisms underlying antimicrobial recalcitrance of polymicrobial biofilms. J Bacteriol. 202(1):e00530-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JW, An JS, Lim WH, Lim BS, Ahn SJ. 2019. Microbial changes in biofilms on composite resins with different surface roughness: an in vitro study with a multispecies biofilm model. J Prosthet Dent. 122(5):493.e1-493e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Cenci T, Cenci MS, Fedorowicz Z, Marchesan MA. 2009. Antibacterial agents in composite restorations for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):CD007819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram Y, Hadany L. 2019. Evolution of stress-induced mutagenesis in the presence of horizontal gene transfer. Am Nat. 194(1):73–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy T, Ghosh A, Pazhani GP, Shinoda S. 2014. Current perspectives on viable but non-culturable (VBNC) pathogenic bacteria. Front Public Health. 2:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AP, Kreth J. 2014. The impact of horizontal gene transfer on the adaptive ability of the human oral microbiome. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 4:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghinejad L, Cvitkovitch DG, Siqueira WL, Merritt J, Santerre JP, Finer Y. 2017. Mechanistic, genomic and proteomic study on the effects of bisgma-derived biodegradation product on cariogenic bacteria. Dent Mater. 33(2):175–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghinejad L, Cvitkovitch DG, Siqueira WL, Santerre JP, Finer Y. 2016. Triethylene glycol up-regulates virulence-associated genes and proteins in Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One. 11(11):e0165760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serkies KB, Garcha R, Tam LE, De Souza GM, Finer Y. 2016. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor modulates esterase-catalyzed degradation of resin-dentin interfaces. Dent Mater. 32(12):1513–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh M, Tam A, Aharoni R, Steinberg D. 2010. Genetic adaptation of Streptococcus mutans during biofilm formation on different types of surfaces. BMC Microbiol. 10:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims KR, Liu Y, Hwang G, Jung HI, Koo H, Benoit DSW. 2018. Enhanced design and formulation of nanoparticles for anti-biofilm drug delivery. Nanoscale. 11(1):219–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira WL, Custodio W, McDonald EE. 2012. New insights into the composition and functions of the acquired enamel pellicle. J Dent Res. 91(12):1110–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomberg DL, Lu Y, Broadnax AD, Hunter RA, Carpenter AW, Schoenfisch MH. 2013. Role of size and shape on biofilm eradication for nitric oxide-releasing silica nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 5(19):9322–9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy SM, Huang J, Gogarten JP. 2015. Horizontal gene transfer: building the web of life. Nat Rev Genet. 16(8):472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Lagemaat M, Grotenhuis A, van de Belt-Gritter B, Roest S, Loontjens TJA, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC, Ren Y. 2017. Comparison of methods to evaluate bacterial contact-killing materials. Acta Biomater. 59:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhou C, Ren B, Li X, Weir MD, Masri RM, Oates TW, Cheng L, Xu HKH. 2017. Formation of persisters in Streptococcus mutans biofilms induced by antibacterial dental monomer. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 28(11):178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong L, Sissons C. 2001. A comparison of human dental plaque microcosm biofilms grown in an undefined medium and a chemically defined artificial saliva. Arch Oral Biol. 46(6):477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HX, Tan L, Tang ZW, Yang MY, Xiao JY, Liu CJ, Zhuo RX. 2015. Highly efficient antibacterial surface grafted with a triclosan-decorated poly(n-hydroxyethylacrylamide) brush. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 7(12):7008–7015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Ren L, Zhang Y, Xue N, Yang K, Zhong M. 2013. Antibacterial activity against Porphyromonas gingivalis and biological characteristics of antibacterial stainless steel. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 105:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Wu R, Fan Y, Liao S, Wang Y, Wen ZT, Xu X. 2014. Antibacterial dental composites with chlorhexidine and mesoporous silica. J Dent Res. 93(12):1283–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Cheng L, Weir MD, Bai YX, Xu HH. 2016. Effects of quaternary ammonium chain length on the antibacterial and remineralizing effects of a calcium phosphate nanocomposite. Int J Oral Sci. 8(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Jones MM, Moussa H, Keskar M, Huo N, Zhang Z, Visser MB, Sabatini C, Swihart MT, Cheng C. 2018. Polymer-antibiotic conjugates as antibacterial additives in dental resins. Biomaterials science. 7(1):287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Yu H. 2017. Spherical micelle formation by mixed quaternary ammonium surfactants with long, and short, tails in ethanol/water solvent and micellar freezing upon solubilising styrene polymerisation. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 513(C):274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Liu H, Weir MD, Reynolds MA, Zhang K, Xu HHK. 2016. Three-dimensional biofilm properties on dental bonding agent with varying quaternary ammonium charge densities. J Dent. 53:73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wang S, Peng X, Hu Y, Ren B, Li M, Hao L, Feng M, Cheng L, Zhou X. 2018. Effects of water and microbial-based aging on the performance of three dental restorative materials. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 80:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]