Abstract

There is overwhelming evidence in the scientific and medical literature that physical inactivity is a major public health problem with a wide array of harmful effects. Over 50% of health status can be attributed to unhealthy behaviors with smoking, diet, and physical inactivity as the main contributors. Exercise has been used in both the treatment and prevention of a variety of chronic conditions such as heart disease, pulmonary disease, diabetes, and obesity. While the negative effects of physical inactivity are widely known, there is a gap between what physicians tell their patients and exercise compliance. Exercise is Medicine was established in 2007 by the American College of Sports Medicine to inform and educate physicians and other health care providers about exercise as well as bridge the widening gap between health care and health fitness. Physicians have many competing demands at the point of care, which often translates into limited time spent counseling patients. The consistent message from all health care providers to their patients should be to start or to continue a regular exercise program. Exercise is Medicine is a solution that enables physicians to support their patients in implementing exercise as part of their disease prevention and treatment strategies.

Keywords: inactivity, exercise, vitals, behaviors, referral

While other determinants of health (genetics, environment, and medical care) influence health outcomes, by far the most important factor contributing to health outcomes is individual lifestyle and behavior.

Physical inactivity underlies many of the chronic conditions that affect people worldwide, has an astonishing array of harmful health effects, and is associated with escalating health care costs. For example, 7 cancers have been linked to a physically inactive lifestyle.1 Depression affects 17 million Americans2 and has been directly linked to insufficient physical activity.3 Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are increasing at a frightening rate. By 2025, the number of people aged 65 years and older with Alzheimer’s disease is expected to reach 7.1 million people. In the United States alone, more than 30 million adults are estimated to have diabetes,4 95% of whom have type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Considering that a new case of diabetes is diagnosed every 21 seconds, it is no surprise that diabetes is the most expensive disease in America, coming in at a price tag of $327 billion annually.5 Underlying the vast majority of T2DM are unhealthy lifestyle behaviors (poor nutrition and insufficient physical activity leading to overweight and obesity). In addition to T2DM, an unhealthy lifestyle (including tobacco use, excessive alcohol intake, poor sleep, and stress) underlies prevalent and costly chronic diseases (eg, heart disease and cancer) leading to premature morbidity and mortality.

While other determinants of health (genetics, environment, and medical care) influence health outcomes, by far the most important factor contributing to health outcomes is individual lifestyle and behavior. Efforts aimed at addressing behaviors, and specifically physical inactivity, are likely to have the greatest impact on the health of populations. A 2015 article from JAMA Internal Medicine6 states, “There is no medication treatment that can influence as many organ systems in a positive manner as can physical activity.” Physical activity and associated improvements in physical fitness are key strategies to improving health.

Dr Steve Blair wrote in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2009 that “physical inactivity is the biggest public health problem of the 21st century.”7 (p. 1) This statement was based on the results of the Aerobic Center Longitudinal Study, which found that fitness was more important than fatness; that improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness reduced premature mortality to a greater extent than improvements in blood glucose or cholesterol levels. Despite all pharmacologic interventions for diabetes or hypercholesterolemia, simply improving aerobic fitness through regular physical activity had the greatest impact on longevity, indicating that exercise is indeed medicine.

Three years later (2012), Lee and colleagues,8 in The Lancet, reported, “In view of the prevalence, global reach, and health effect of physical inactivity, the issue should be appropriately described as pandemic, with far-reaching health, economic, environmental and social consequences.” (p. 219) The authors concluded that physical inactivity causes 1 in 10 premature deaths worldwide. If inactivity decreased by 25%, more than 1.3 million deaths worldwide could be averted every year. Furthermore, deaths attributable to a physically inactive lifestyle were nearly equal to those from smoking, giving rise to the saying, “Sitting is the new smoking.”8

Exercise is a “medicine” that can prevent and treat chronic disease; those who “take it” live longer and with a higher quality of life. In 2018, the Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (https://health.gov/PAGuidelines/) released a Scientific Report that would be the foundation for the second edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans9 issued by the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition. This report summarized the scientific evidence regarding the benefits of a physically active lifestyle on physical and mental health. It builds on the data that informed the first guidelines in 2008 and incorporates new research from over the past 10 years. The power and contribution of physical activity and exercise on overall health, quality of life, and disease-specific prevention and treatment is staggering (Table 1). A meta-analysis of studies evaluating the relative effectiveness of pharmaceutical versus physical activity interventions found that regular exercise was just as effective as commonly prescribed medications in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, treatment of heart failure, prevention of diabetes, and even more effective than medication in the rehabilitation of patients after a stroke.10

Table 1.

| Children | |

| 3 to <6 years | • Improved bone health and weight status |

| 6 to 17 years | • Improved cognitive function

• Improved cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness • Improved bone health • Improved cardiovascular risk factor status • Improved weight status or adiposity • Fewer symptoms of depression |

| Adults, all ages | |

| All-cause mortality | Lower risk |

| Cardiometabolic conditions | • Lower cardiovascular incidence and mortality (including heart disease and stroke) • Lower incidence of hypertension • Lower incidence of type 2 diabetes |

| Cancer | Lower incidence of bladder, breast, color, endometrium, esophagus, kidney, stomach, and lung cancers |

| Brain health | • Reduced risk of dementia

• Improved cognitive function • Improved cognitive function following bouts of aerobic activity • Improved quality of life • Improved sleep • Reduced feelings of anxiety and depression in healthy people and in people with existing clinical syndromes • Reduced incidence of depression |

| Weight status | • Reduced risk of excessive weight gain

• Weight loss and the prevention of weight regain following initial weight loss when a sufficient dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is attained • An additive effect on weight loss when combined with moderate dietary restriction |

| Older adults | |

| Falls | • Reduced incidence of falls • Reduced incidence of fall-related injuries |

| Physical function | • Improved physical function in older adults with or without frailty |

| Individuals with preexisting medical conditions | |

| Breast cancer | • Reduced risk of all-cause and breast cancer mortality |

| Colorectal cancer | • Reduced risk of all-cause and colorectal cancer mortality |

| Prostate cancer | • Reduced risk of prostate cancer mortality |

| Osteoarthritis | • Decreased pain

• Improved function and quality of life |

| Hypertension | • Reduced risk of progression of cardiovascular disease

• Reduced risk of increased blood pressure over time |

| Type 2 diabetes | • Reduced risk of cardiovascular mortality

• Reduced progression of disease indicators: hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, blood lipids, and body mass index |

| Multiple sclerosis | • Improved walking

• Improved physical fitness |

| Dementia | • Improved cognition |

| Some conditions with impaired executive function | • Improved cognition |

Benefits in boldface are those added in 2018; benefits in normal font are those noted in the 2008 Scientific Report. Only outcomes with strong or moderate evidence of effect are included in the table.

Source. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Integrating the Evidence, 2018. health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report, pp. D5 to D6.

To manage spiraling health care costs associated with lifestyle-related chronic diseases, health care is moving toward value-based and population health models of care. Lifestyle interventions that provide guidance and support to help patients with common chronic conditions to successfully adopt and maintain a habit of regular physical activity will be instrumental.

Imagine a pill that conferred the established health benefits of exercise and/or regular physical activity with minimal adverse effects and a multitude of positive effects causing patients to “feel better, function better, and sleep better.”9 Physicians would surely prescribe that pill to every patient, pharmaceutical companies would produce and market it, health plans would surely pay for it, and every patient would ask for it.

Exercise Is Medicine

The Exercise is Medicine (EIM) initiative was founded in 2007 by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) with the goal of making physical activity assessment and exercise prescription a standard part of the disease prevention and treatment paradigm for all patients. Certainly, evidence calls for nothing less than a global initiative to make this happen. As was suggested earlier, it is obvious that if such compelling evidence had been developed around a pill or surgical procedure, every doctor around the world would want to prescribe it to their patients; in fact, it would be malpractice not to prescribe it to every patient, every visit, regardless of medical specialty.

A national launch for the EIM initiative was held on November 5, 2007, at the National Press Club in Washington, DC. This launch was chaired by then ACSM President-Elect Robert Sallis, MD, and incoming American Medical Association President, Ron Davis, MD. Also attending the launch was the acting US Surgeon General, Dr Steven Galson, who was also a strong advocate for promoting physical activity to influence health, along with Melissa Johnson (then Executive Director of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports), and Jake Steinfeld (Chairman of the California Governor’s Council for Physical Fitness and Sports).

The first 5 years of EIM mainly involved getting the word out, building infrastructure, and establishing collaborations. During the past several years, there have been a variety of efforts to move EIM forward in an increasingly complex and changing health care landscape, including education, partnerships, outreach, and policy work. Some key highlights include the following:

Building an EIM global health network, including regional centers that coordinate EIM partnerships in countries around the world. These are linked by a robust website designed to enhance communication and collaboration across the network.

Establishment of the World Congress on Exercise is Medicine as a central component of the ACSM annual meeting and as a place to share the latest research and build collaborations across the country and around the world.

Growth of a vibrant EIM on-campus network that is now strong and expanding, including 275 college and university campuses around the world.

Development of a global EIM Continuing Medical Education course to teach health care providers how to assess, counsel, and refer patients for physical activity prescription to treat and prevent chronic disease.

Creation of an EIM Credential to recognize qualified and certified fitness professionals who are prepared to receive and work with patients referred from health care providers.

Successful piloting of the EIM Solution model (linking clinical care/Physical Activity Vital Sign [PAVS]) to community networks) at the Greenville Health System (now Prisma Health) and the Greenville (South Carolina) YMCA.

EIM partnerships with various health care associations and fitness organizations that have helped drive important programs to improve physical activity including the Surgeon General’s Call to Action on Walking, the Every Body Walk Collaborative, Walk with a Doc, Park Rx America, and the Prescription for Activity Task Force.

The vision of EIM is to make physical activity assessment and exercise prescription a standard part of the disease prevention and treatment paradigm for all patients and to connect health care with evidence-based physical activity resources. The initiative proposes that physical activity assessment and promotion be the standard of care for every patient, at every visit and as part of every treatment plan.11

It is recommended that physical activity be recorded as a vital sign, just as other modifiable risk factors are routinely assessed (eg, blood pressure, weight, smoking).11-14 Two or 3 simple questions can be integrated into the health history form/electronic health record (EHR) to identify those patients who are not meeting the federal guidelines for physical activity. This allows patients to be identified for population health interventions or physical activity advice or referral. Patients are advised to meet the recommended amount and types of physical activity and, at a minimum, encouraged to reduce sedentary time by integrating short bouts (of any duration) of light to moderate intensity physical activity over the course of the day (eg, taking stairs, walking when possible, standing frequently during seated tasks). The 2018 Physical Activity recommendations are summarized in Table 2. Patients with various chronic medical conditions may benefit from more specific guidelines, modifications, and precautions.15 These are provided in the “EIM Rx for Health” series of patient handouts (www.exerciseismedicine.org/rx-for-health-series).16 In addition, digital and print materials to promote physical activity to various segments of the population can be found as part of the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health’s “Move Your Way” campaign (https://health.gov/paguidelines/moveyourway/).

Table 2.

2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans.

| The Miracle Drug: Exercise is Medicine® |

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In an era of spiraling health care expenditures, getting patients to be more active may be the ultimate low-cost therapy for achieving improved health outcomes. Studies show that regular physical activity (PA) has health benefits at any body weight and is critical for long-term weight management. Decades of research have shown that exercise is as effective as prescription medication in the management of several chronic diseases. Just as weight and blood pressure are addressed at nearly every health care visit, so should attention be given to PA. Assessment: Use the Physical Activity Vital Sign to Assess Weekly PA Levels Add these 2 simple questions to the health history form and electronic health record to determine if the patient is meeting the PA guidelines: | ||||||

| 1. On average, how many days per week do you engage in moderate to vigorous PA (like brisk walking)? | ____ Days | |||||

| 2. On average, how many minutes do you engage in PA at this level? Total Activity (days/week x minutes/day) = ___minutes/week |

____ Minutes | |||||

|

Brief Advice/Prescription: Basic Exercise Recommendations

• Encourage your patient to meet the PA guidelines (see chart). At minimum, adults should be more active over the course of a day (ie, take frequent breaks from sitting, walk the dog, use the stairs). Every minute counts! Children and adolescents should engage in sports, dance, outdoor recreation, and active games. • Provide the EIM “Sit Less. Move More” handout to your patients. The EIM Rx for Health Series also provides condition-specific handouts. | ||||||

| 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans | ||||||

| Age (years) | Aerobic Activity Recommendations | Muscle Strengthening Recommendations | ||||

| 6-17 | 60 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity (PA)/day including at least 3 days of vigorous PA/week | 3 days/week and included as part of the 60 minutes of daily PA. Also include bone-loading activity. | ||||

| 18-64 | 150-300 minutes of moderate PA/week 75 minutes of vigorous PA/week or equivalent combination spread throughout the week |

Muscle strengthening activities at moderate or greater intensity (all major muscle groups) on 2 or more days/week | ||||

| 65+ | Same as adults, or be as active as abilities and health conditions allow | Same as adults, but include balance training and combination activities (strength and aerobic training together) | ||||

| All ages | Sit less. Move more. All physical activity counts. | |||||

|

Referral and Resources

• Advise patients to take advantage of local parks and recreation programs. Develop referral relationships with fitness facilities and exercise professionals who can provide support and guidance. • Visit the EIM website at www.exerciseismedicine.org for the EIM Health Care Provider Action Guide. Health care providers who are more active, are more likely to counsel patients regarding physical activity. It’s not enough to “talk the talk,” you have to literally “walk the walk.” YOU will feel better and move better as well. | ||||||

Copyright © 2019 Exercise is Medicine.

While the assessment and promotion of physical activity fits naturally into the “whole patient” medical management model provided in primary care/family medicine, the message should be delivered by every health care provider, regardless of specialty, since the effects of physical activity (or lack of it) contribute to an abundance of medical conditions. EIM is best delivered efficiently using every member of the health care team, including medical assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physical therapists, exercise physiologists, dietitians, diabetes educators, health coaches, and even front desk staff in specific roles. An “EIM Health Care Provider Action Guide”17 has been developed to assist physicians and other health care providers in integrating EIM into the clinical setting (https://exerciseismedicine.org/).

EIM recommends that health care providers refer patients to appropriate community resources to help them integrate physical activity into their lives. These include programs, places, and professionals (the 3 Ps) in their communities or self-directed resources such as activity trackers, mobile phone apps, websites, bike share programs, and local parks. Each patient is likely at a different stage of readiness to engage in exercise or physical activity and presents with unique health and environmental challenges, so customizing exercise or physical activity recommendations is beneficial. Because most clinicians do not have the time nor the expertise to provide in-depth physical activity counseling, they should begin to expand their reach of care by merging the health care industry with the fitness industry. The fitness industry must take steps to clearly differentiate and support those qualified fitness professionals who have the education, certification, training, and experience to work with referred patients at various levels of risk or with common chronic medical conditions.

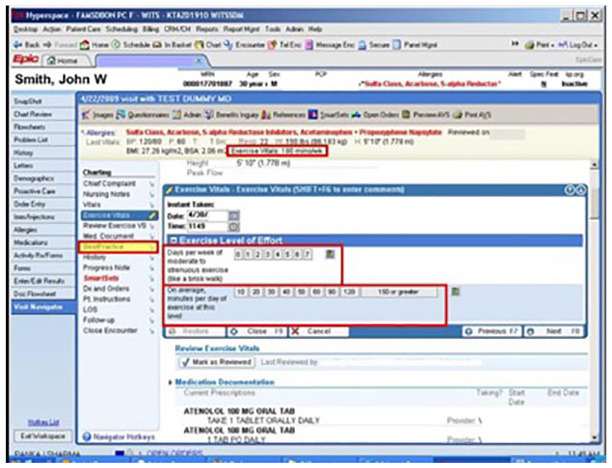

One of the early adopters of EIM was Kaiser Permanente (KP). The Exercise Vital Sign (EVS) was launched in Kaiser Permanente’s Southern California region in October 2009 to routinely assess the exercise habits of patients at all visits. Founded in 1945, KP is one of the nation’s largest health plans, serving almost 12 million members. As a staff model health maintenance organization, KP members pay a monthly premium and receive all of their health care from KP physicians and staff at KP facilities. Therefore, KP has a tremendous incentive to invest in disease prevention and keep patients healthy, thereby avoiding the costs associated with caring for more advanced medical conditions. For this reason, helping patients become more physically active is a key priority in the organization’s quest to help patients achieve total health.

The EVS has been a tremendous success at KP and has spread to virtually all Kaiser territorial regions. A study of 2.1 million adult patients from KP in Southern California demonstrated that within the first year of implementation, they were able to capture an EVS on 85% of eligible patients.18 This compares favorably with the implementation of a smoking status query (95%) recorded in an EHR.19

At the same time, KP has made a big push to encourage physicians and staff to be role models of an active lifestyle for their patients. This started with their long running marketing campaign called “Thrive.” The tag line for this campaign is, “At Kaiser Permanente, we want you to live well, be well and thrive.”. This has been both an external and internal campaign and encourages all KP employees to live the brand. In keeping with this message, internal campaigns called “Thrive Across America” and “KP Walk” have encouraged staff to join together to be more active and to get out and walk. At the same time, past KP Chairman and CEO George Halvorson launched a campaign called “Every Body Walk!” (www.everybodywalk.org) in January 2011. This was a nonbranded campaign designed to get America walking that eventually led the US Surgeon General to issue a Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities (https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/walking/). Featuring an interactive website at the hub of the campaign, it contains numerous videos and articles designed to inspire and inform patients about how and why they should start walking.

Physical Activity Vital Sign

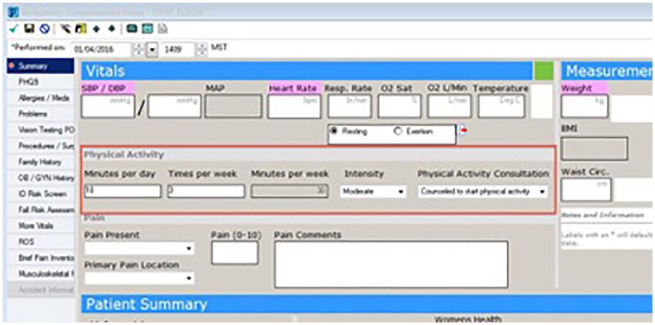

Drs Steve Blair and Tim Church, recommended in their JAMA publication in 2002 that the recommended accumulation of 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity at least 5 days a week as weight be addressed in some manner at nearly every physician visit, just as weight is.20 These forward-thinking scientists also stated that the “medical community needs to lead in communicating the importance of physical activity for health and weight maintenance.” However, it took 7 years for KP to implement the EVS in their EHR and clinical practices, and Intermountain Healthcare launched the PAVS in 2013 (Figures 1 and 2). Like body weight or blood pressure, the EVS or PAVS is collected and recorded at every visit, providing an opportunity for health care providers to discuss the importance of physical activity in the promotion of health and the prevention and management of disease.

Figure 1.

Kaiser Permanente exercise vital sign (EVS).

Figure 2.

Intermountain Healthcare physical activity vital sign.

Successful promotion of physical activity in health care settings not only starts with the PAVS but is also dependent on the PAVS. The PAVS is a self-reported measure, asked by a medical or clinical assistant at the start of a clinical encounter. It is recorded in the EHR for the physician to review and interpret. Based on the minutes per week and intensity of physical activity reported, the physician can provide advice to start, increase, maintain, or modify current physical activity levels, provide a personalized physical activity prescription, and refer the patient to a fitness professional for education, coaching, and support. The PAVS serves as a prompt for health care providers to address physical activity during clinical encounters. Whether that visit is for diabetes, high blood pressure, low back pain, mental illness, or a physical examination, knowing that person’s physical activity level, and providing counseling, is a key strategy to improving health.21

What Can Busy Physicians Do to Encourage Physical Activity?

Despite the overwhelming evidence supporting the fact that physical activity is an essential element in both the prevention and management of numerous medical conditions, physicians typically have a poor track record when it comes to promoting physical activity with their patients. In 2009, Katz et al22 highlighted that only 45% of patients admitted for chest pain received counseling on physical activity. Overall, physicians insufficiently use physical activity as either a treatment modality or preventative tool in the care of their patients. The National Health Interview Study found that only 32% of patients receive advice from their physician or other health care professional to exercise or continue being physically active during their visit with a physician.23

The most commonly cited reason that physicians list for not including physical activity counseling in their practice is a lack of time.24 With many competing demands forced upon today’s physicians, as well as the fact that most physicians work in a productivity-based health care model that rewards physicians for seeing more patients, the utilization of any behavioral counseling in a practice is often overlooked. Even brief physical activity counseling can take 3 to 5 minutes, and is typically not feasible, let alone reimbursable.

Additionally, physicians often lack confidence in their abilities to prescribe exercise as most have not had any formal education related to physical activity in medical school. In 2015, Cardinal et al25 studied curricula of 170 allopathic and osteopathic medical schools and found that only 21.2% had one course related to physical activity available for their medical students and only 12.2% had a required course. Typically, these courses focused on exercise physiology or sports medicine with only 8.1% and 4.7% educating on preventive or lifestyle medicine, respectively.25

A recognized area of weakness in medical training, newer schools are embracing the concept of teaching medical students about maintaining their own well-being through physical activity, nutrition, and stress management. By training young medical professionals in these concepts early in their careers, the hope is that future generations of physicians will be more likely to apply these concepts to the care of their patients.26

Another potential barrier to addressing physical activity is the physician’s perception of patient resistance to physical activity based on cultural, environmental, safety, or financial issues. Despite these perceived barriers, physicians need to be encouraged to think creatively to find ways to connect these patients with the appropriate means to be physically active within the constraints of their situation. Frequently, local malls can provide safe areas to walk. Schools will share their facilities before school, after school, and on the weekends, and many community programs exist that offer opportunities to be active in ways that resonate with a patient group. Having preprinted lists of no cost and low-cost community resources available can make physician referrals to these programs a seamless process in the midst of a busy day. EIM offers a Physical Activity Resources template that can be customized for a given practice or community (www.exerciseismedicine.org).

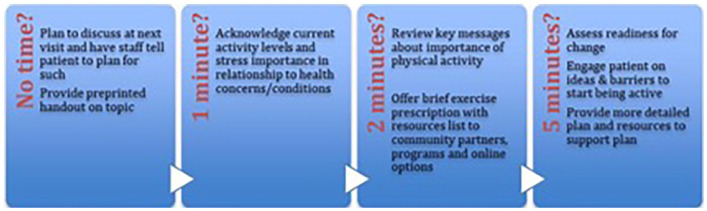

Several proposed approaches exist in terms of creating time to discuss physical activity in the context of a busy clinical practice. A physician or other health care provider does not need to commit an entire visit to counseling on physical activity, but rather can tailor the amount of time to what is available in the situation (Figure 3). Alternatively, busy physicians can enlist the help of their staff to do the bulk of the heavy lifting when it comes to exercise counseling. A brief acknowledgement of a patient’s current activity level followed by having a nurse or medical assistant review ways to begin the process of becoming active still can be extremely impactful in the lives of patients. Physicians can also make use of the prescription pad/form to promote physical activity (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Making time to counsel on physical activity.

Figure 4.

Kaiser Permanente Rx pad.

Medical providers should also consider partnering with those in their health system and/or communities who have a passion for and expertise in physical activity counseling. A Primary Care Sports Medicine physician is often the best option in a medical group based on their training and their belief in promoting exercise for patients. Many Sports Medicine departments can offer exercise prescription counseling that is covered by insurance provided that the patient has one or more chronic medical conditions that can be used as their billing diagnosis. Patients are typically scheduled for visits billed for by time, and the visit is often a combined visit between the Sports Medicine physician and an Exercise Physiologist who can review prescribed exercises with the patient. Another option is to collaborate with those in the community such as personal trainers, nurse educators, dietitians, and exercise scientists.

Integrating Fitness Into Health Care

Integrating fitness into health care on a large scale has been a challenge in most US health systems. Currently, traditional US medical systems have operated on a fee-for-service model of health care with little to no incentive to promote fitness and physical activity to improve health and manage or prevent chronic illness. As the system shifts to pay for value with a focus on population health, there will hopefully be both a shift for increased administrative support to incorporate physical activity and fitness in ways that those in lifestyle and sports medicine would desire.

Until such time where fitness is fully integrated into the US health care model, it is necessary to champion the role of fitness and physical activity in health care within individual health care systems. Numerous success stories exist on how systems that include fitness and physical activity as part of their approach see improved health care measures in addition to decreased health care costs. Nguyen et al27 performed a 2-year study that demonstrated a reduction in health care utilization and spending using a health-plan sponsored health club membership in older adults with diabetes. Examples of larger scale initiatives include the KP, Intermountain Healthcare, and Prisma Health (formerly Greenville Health System and Palmetto Health) initiatives that have integrated the use of the PAVS within their systems to have physical activity be at the forefront of all medical encounters. These systems have provided valuable insights for others in terms of successful implementation strategies, methods to engage providers, and marketing the concept to patients.28

At the individual practice level, physicians should begin by using the PAVS as a first step in championing the process for their own health systems. By role modeling the concept, physicians can build traction in establishing the routine measurement of PAVS as the standard of care for all health care providers. In addition, the routine use of the PAVS results in higher levels of exercise counseling documentation and more exercise referrals being placed for patients.26 Health care providers should also utilize the many free resources available within the EIM website that includes patient handouts on exercise with a variety of chronic medical conditions as well as information on the exercise prescription itself (www.exerciseismedicine.org).

Creating Meaningful Communication and Seamless Referrals Between Health Care Professionals and Health Fitness Professionals

As physicians begin the process of discussing physical activity in their practices, it is essential that they also establish ties with fitness professionals in their community in order to provide patients with resources to continue that important conversation and implement exercise recommendations or prescriptions. It is rarely possible for the busy clinician to outline an entire program with their patients, nor should they feel obligated to do so. Rather, they should look to those fitness professionals in their communities who can take the lead on implementing physical activity strategies. Whether that be through direct referrals to specific providers or a preprinted handout that lists options for patients, physicians owe it to their patients to have these resources available. By taking the time to start physical activity counseling with patients, the physician is acknowledging their belief in the importance of physical activity on health. Going the extra step to provide ways to implement the suggestions and/or receive additional counseling on how to start an exercise program demonstrates that they are ready and willing to be part of the process.

A Challenge to the Health Club and Fitness Industry

Traditionally, the focus of health club membership has been the 25- to 35-year-old demographic with little attention paid to potential members who may have or are recovering from a chronic illness or medical condition. In fact, many commercial clubs turn away potential members if they reveal on medical histories heart attacks, strokes, pulmonary disease, or diabetes. Commercial clubs (for-profits) seem to have locked into young and healthy members while seemingly ignoring a growing population of baby boomers who may have a chronic medical condition. Clubs should not ignore their base of membership support but should consider the integration of health care into health fitness by adopting the EIM model.

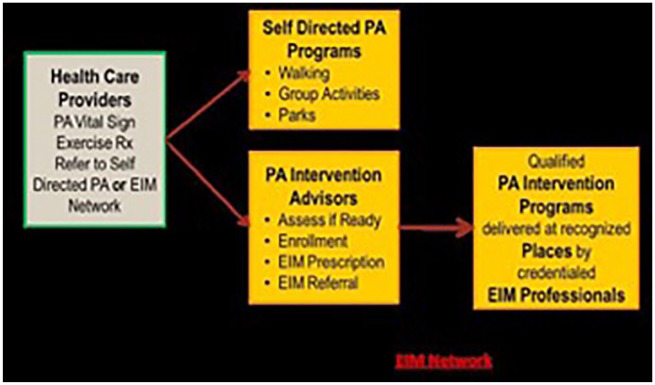

A second challenge is for fitness professionals to consider changing their focus from clients to patients, from “abs and buns” to “hearts and lungs.” This change in emphasis from routine personal training or group training will require the fitness professional to learn new skills and have knowledge of chronic diseases and how to develop the right exercise program for this client (patient) population. Together, the health care industry and the health fitness industry should merge into a single and seamless referral system. Health care providers can choose to provide patients with self-directed physical activity programs (like walking, biking, and swimming) or they can choose to send their patients to physical activity intervention programs delivered at recognized clubs by credentialed fitness professionals (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Health care providers referral mechanism.

Fitness Professional Credential Verification and Locator Services

In 2008, national certification agencies that are accredited by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA; https://www.credentialingexcellence.org/ncca) organized the Coalition for the Registration of Exercise Professionals (CREP), which developed for the first time the United States Registry of Exercise Professionals (USREPS; http://www.usreps.org/). USREPS is a searchable database that physicians and health care providers can use to identify certified fitness professionals in their communities. The database can also be used to verify employees’ certification and determine the international portability of certifications. The registry is searchable by name, credential, credential number, certification organization, name, city, state, and even zip code. With over 250 fitness-related certifications varying in training, ranging from a credential purchased on the internet to sitting for a written and practical examination, USREPS provides verification of certifications that are accredited by the NCCA, which holds high standards for certification organizations.

A much smaller database and one that includes ACSM Certified Personal Trainer (ACSM-CPT), ACSM Certified Exercise Physiologist (ACSM-EP), Certified Clinical Exercise Physiologist (ACSM-CEP), and ACSM Certified Group Exercise Instructor (ACSM-GEI) is the ACSM ProFinder (https://www.acsm.org/get-stay-certified/find-a-pro). The ACSM ProFinder is a database searchable by name, certification level, city, state, country, and zip code. The advantage of the ACSM ProFinder over USREPS is the ability to contact the fitness professional by using a unique e-mail address.

The Exercise Is Medicine Greenville Experience

One example of a multilevel partnership working to ameliorate the detrimental effects of physical inactivity at the patient and population health level is Exercise is Medicine Greenville (EIMG) located in Greenville, SC. EIMG is the first partnership across a medical school (University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville), health care system (Prisma Health), and community organization (YMCA of Greenville) that combines resources to educate physicians on the clinical benefits of exercise. The physicians connect patients via identification, prescription, and referral from the health system to the community for an evidence-based clinical exercise-centered lifestyle program to improve outcomes for those experiencing or at-risk for chronic diseases. The program was designed based on a Population Health Management model to address multiple levels across the Socio-Ecological Model using the 3 stakeholders’ input. Physicians and other qualified health care providers (NP, PA) work with an interdisciplinary team (such as RNs, RDs, and diabetes educators) to refer patients to EIMG where patients then undertake a supervised 12-week clinical exercise and health behavior change intervention in two 1-hour sessions per week with qualified, credentialed EIMG professionals (EIMG Pros) in an easily accessible community-based setting.

The EIMG program was created as an evidence-based, flexible, and adaptive rolling enrollment, community-based clinical exercise program guided by social-cognitive theory, with 2 focused clinical exercise modules serving Prisma Health patients with (1) cardiometabolic diagnoses or (2) musculoskeletal/pain problems. The rolling enrollment features allow patients to onboard in less than 10 business days (maximizing readiness), and new patients can learn from more established patients who have been participating in the program. At every session, patients are also provided 1 of 24 EIMG Patient Education Handouts to provide active health learning during the EIMG class sessions. The patient education handouts increase the patient’s understanding about the importance of exercise and physical activity in chronic disease prevention and management, and to assist the patient in applying that knowledge to encourage behavior change. A variety of topics cover components of exercise and physical activity, diet and nutrition, stress management, goal setting, and social support.

Because of the partnership with the YMCA of Greenville, no patient is turned away for inability to pay for the program; in-need patients are provided scholarships to attend the program as well as to continue membership at the same rate on graduation. The overarching goal is to help patients begin to meet the national physical activity guidelines of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week and 2+ days per week of strength training, as well as to create health behavior change for a more physically-active lifestyle and increase patient self-efficacy to independently exercise at graduation from the program.

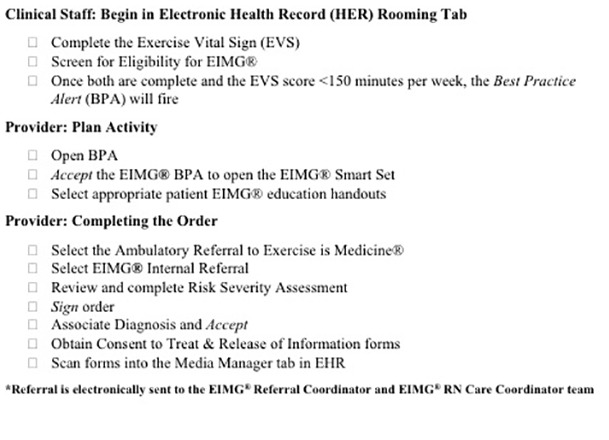

The EIMG experience begins at the clinic visit with Prisma Health providers using the EHR to capture the patient’s EVS. Once the EVS is obtained, physicians inform qualified patients (ambulatory patients who lack 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity physical activity, and/or have or are at risk for one or more of the chronic conditions of T2DM, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity) about EIMG. Providers then review any risks, provide health education, electronically approve the EIMG order set, and refer the consenting patient to the EIMG Referral Coordinator and EIMG RN Care Coordinator team (Figure 6). The Coordinator of the team contacts the patient, confirms eligibility and interest, reviews the patient’s preferred location and ability to pay (or qualify for a scholarship), and then electronically sends all pertinent information to the community fitness center site coordinator, where the patient is scheduled for onboarding. The loop of communication is closed back to the referring provider through the EHR upon patient graduation from the program or if the patient decides to not continue.

Figure 6.

Exercise is Medicine Greenville clinical workflow process.

Once patients are onboarded, the intervention is executed by the EIMG Pros in either Prisma’s medical fitness center (“Life Center”) or 1 of 5 Greenville-based YMCAs. All EIMG Pros are required to have a bachelor’s degree or higher in exercise science or related field, possess a minimum of a personal training certification (from a national certification organization that is accredited by the NCCA), and undergo the national ACSM EIM credentialing process (Level 2; http://www.acsm.org/get-stay-certified/get-certified/specialization/eim-credential). For additional quality assurance in working with a clinical population, EIMG Pros must then complete the following before they can begin actively teaching EIMG class sessions:

The EIMG Pro staff training webinars to orient EIMG Pros to the program design, implementing the program, and understand the policies, procedures, and expectations

HIPAA and social media online courses

National Institutes of Health Protecting Human Subjects Research online course to ensure the EIMG Pros understand ethical and safe practices for working with clinical patients

REDCap data collection training for research

An EIMG Fitness Professional Training Manual, available to the EIMG Pro, consists of all content included in the EIMG Pro Staff Training webinars, in addition to the following:

The EIMG referral process and operational workflow

EIMG staff procedures

EIMG program documents, and REDCap guide

Patient and EIMG Pro related resources

EIMG Patient Education Handouts

EIM Prescription for Health Series

Continuing education at least once per year is required for all EIMG Pros as a means for improving program implementation. To accomplish this, EIMG hosts 2 EIMG Pro Training Workshops every year (Spring and Fall) to present various topics such as procedural review, operational updates, and clinical exercise physiology instruction.

An EIMG Advisory Board, composed of stakeholders from participating partners, meets monthly to provide oversight of the program for regular review and revisions. The EIMG Policies and Procedures provide direction, guidelines, and boundaries for implementing the EIMG program and ensuring compliance with the rules and regulations of the program for all parties involved. The manual guides all major decisions and actions for ethical execution and operations of program principles as applied to working with clinical populations. All EIMG staff are required to review the policies and procedures and sign an acknowledgement form prior to commencing work within the EIMG program, and specifically with EIMG patients.

The EIMG program is currently implemented across 18 clinics of different departments of Prisma Health Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, and in specialty clinics such as Oncology, Bariatrics, Endocrinology, and Prisma’s Diabetes Prevention Program. Graduation rate is over 60% with currently over 170 graduates. A small but statistically significant improvement in body weight has been observed after graduation, with a strong and statistically significant improvement in both systolic and diastolic blood pressures observed in patients who onboarded due to a hypertension diagnosis. Patient graduates who complete exit surveys score all components of the program (health care provider, project coordinator, and EIMG Pro) using a Likert-type scale (low = 1; high = 5) as highly satisfactory (4.56).

EIM International

Not long after EIM was launched in the United States, interest was expressed by individuals from countries also facing an epidemic of physical-inactivity related diseases. There are currently EIM National Centers in 37 countries on 6 continents (North America, South America, Asia, Europe, Africa, and Australia), with 3 EIM Regional Centers in Asia, Latin America, and Europe. An EIM Global Launch Guide (https://exerciseismedicine.org/) helps countries form a leadership team composed of an interdisciplinary group of stakeholders. The EIM Global Network facilitates communication, learning, and collaboration among colleagues around the world. Because the governmental, academic, health care, and cultural landscapes are different within each country, EIM National Center Advisory Boards establish goals and strategic initiatives to guide efforts within their countries.

For example, EIM Singapore has taken a systematic approach to integrating EIM into disease management pathways. They have designed a template and progressively incorporated the PAVS into electronic case notes in various clinical departments at Changi General Hospital—with full adoption expected in 2020. They then plan to roll it out to the other 3 hospitals of the SingHealth Cluster. EIM Singapore is working with specialties such as family medicine, cardiology, rehabilitation medicine, oncology, and obstetrics and gynecology to incorporate exercise interventions into their respective disease management pathways. A mainstay of EIM Singapore’s mission is to train physicians in exercise prescription. They are also training community health counsellors called Health Peers (lay persons trained to coach peers to adopt a healthy lifestyle) in prescribing exercise and working with community partners such as the Health Promotion Board, Sport Singapore, and religious organizations to promote physical activity.

In Poland, the EIM National Center team has been working with the Polish Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Sport, and the National Institute of Public Health to incorporate physical activity into health care systems. They are educating medical students and fitness professionals during annual conferences, lectures, and workshops, and have started 2 community-based projects, “Walk for Health—Invite Your Doctor” and “Active Family,” obtaining significant media coverage for EIM.

EIM Latin America has focused efforts on educating medical students as well as offering EIM workshops for health care providers and exercise professionals. Chile has introduced an EIM Online Course as part of the Education Centre of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Chile, one of the most recognized universities in the country, reaching hundreds of medical students and health care providers at different hospitals and health care centers. In spite of political and social challenges in the region, most EIM National Centers are working with private and public health systems to integrate physical activity as a way to promote health and treat/control chronic diseases, engaging with national task forces to implement public policies and update national physical activity recommendations to combat the significant increase in obesity in adults and children in Latin America.

Summary

The evidence on the cost and health burdens of physical inactivity is overwhelming, and the evidence for the benefits of regular exercise in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease is irrefutable. Health care providers have an obligation to inform patients about the risks of being sedentary, and to prescribe regular exercise. The American College of Sports Medicine’s Exercise is Medicine program has developed the necessary tools and resources for health care providers, fitness professionals, and even patients to get started. At a minimum, all health care encounters should include the PAVS, regardless of specialty. Physicians are trusted and respected professionals, and a recommendation to be more active, accompanied by a prescription and referral to a fitness professional has been demonstrated to improve physical activity and health. A merger of health care and fitness programs in communities around the world is no longer an option. Exercise is Medicine that all patients need to take.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article is the result of a keynote presentation of Dr Walt Thompson at Lifestyle Medicine 2019 held at the Rosen Shingle Creek Resort, Orlando, Florida, on October 30, 2019.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

Contributor Information

Walter R. Thompson, College of Education & Human Development, Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Robert Sallis, UC Riverside School of Medicine, Fontana, California.

Elizabeth Joy, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Carrie A. Jaworski, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

Robyn M. Stuhr, Exercise Is Medicine®, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Jennifer L. Trilk, Lifestyle Medicine Education University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, Greenville, South Carolina.

References

- 1. Rezende LFM, Sá TH, Markozannes G, et al. Physical activity and cancer: an umbrella review of the literature including 22 major anatomical sites and 770 000 cancer cases. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:826-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute of Mental Health. Major depressive: prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml#part_155029. Accessed December 4, 2019.

- 3. Schuch FP, Vancampfort D, Firth J, et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:631-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2017. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:917-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manini TM. Using physical activity to gain the most public health bang for the buck. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:968-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blair SN. Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:1-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effects of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2018. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee scientific report. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/PAG_Advisory_Committee_Report.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2020.

- 10. Naci H, Ioannidis JP. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1414-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lobelo F, Young DR, Sallis R, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e495-e522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sallis RE, Matuszak JM, Baggish AL, et al. Call to action on making physical activity assessment and prescription a medical standard of care. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2016;15:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stoutenberg M, Shaya GE, Feldman DI, Carroll JK. Practical strategies for assessing patient physical activity levels in primary care. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1:8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Golightly YM, Allen KD, Ambrose KR, et al. Physical activity as a vital sign: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Exercise is Medicine. Rx for health series. https://www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/rx-for-health-series/. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- 17. Exercise is Medicine. Health care provider action guide. http://www.exerciseismedicine.org. Accessed December 13, 2019.

- 18. Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2071-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Norris JW, 3rd, Namboodiri S, Haque S, Murphy DJ, Sonneberg F. Electronic medical record tobacco use vital sign. Tob Induc Dis. 2004;2:109-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blair SN, Church TS. The fitness, obesity, and health equation: is physical activity the common denominator? JAMA. 2004;292:1232-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grant RW, Schmittdiel JA, Neugebauer RS, Uratsu CS, Sternfeld B. Exercise as a vital sign: a quasi-experimental analysis of a health system intervention to collect patient-reported exercise levels. J Gen Int Med. 2014;29:341-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Katz DA, Graber M, Birrer E, et al. Health beliefs toward cardiovascular risk reduction in patients admitted to chest pain observation units. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:379-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barnes PM, Schoenborn CA. Trends in adults receiving a recommendation for exercise or other physical activity from a physician or other health professional. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(86):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McPhail S, Schippers M. An evolving perspective on physical activity counselling by medical professionals. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cardinal BJ, Park EA, Kim M, Cardinal MK. If exercise is medicine, where is exercise in medicine? Review of US medical education curricula for physical-activity related content. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:1336-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jaworski CA. Combating physical inactivity: the role of healthcare providers. ACSM’s Health Fitness J. 2019;23:39-44. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nguyen HQ, Maciejewski ML, Gao S, Lin E, Williams B, Logerfo JP. Health care use and costs associated with use of a health club membership benefit in older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1562-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sallis R, Franklin B, Joy E, Ross R, Sabgir D, Stone J. Strategies for promoting physical activity in clinical practice. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;57:375-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]